Problem-solving is all about liberating ourselves from stuckness. You know you have a problem when you want to do something but you don’t know what to do. As we’ve seen in Chapter 1, we have an astonishing array of mental tools and techniques to unstick our thinking. No other animal on earth is such a versatile problem-solver.

Becoming a better problem-solver, then, means becoming even more versatile. All of us favour some forms of thinking over others. We’re as much creatures of habit as of creativity. We develop the thinking styles we find successful, and allow the less successful styles to wither. Becoming more versatile means exploiting the styles of thinking we’re good at and growing those styles we’ve used less.

A good place to start is to examine what we already do well. Understanding our preferred problem-solving style is useful in all sorts of ways. It will help us to see why we approach problems in the way we do. But it will also help us to see where we can develop new thinking skills.

This chapter will help you identify the problem-solving styles that work well for you and where your strengths lie. You’ll also begin to see where you can grow new skills, to help you solve problems in new ways.

How to assess your preferred problem-solving styles

On the next page you’ll find four sets of problem-solving behaviours. Mark as many of the behaviours as you think apply to you. You can mark as many or as few behaviours as you wish. When you’ve completed the questionnaire, we’ll explore what your answers might mean. Try not to turn to the following pages before completing the questionnaire.

This isn’t a personality test. It’s certainly not in any way scientific. We’re looking at preferred behaviours: the things you’re most comfortable doing. We can generalize from those behaviours to a set of preferred thinking styles, but these are not in any way intended to indicate what kind of person you are. Thinking styles, like other styles, are behaviours we can choose to adopt.

It’s up to you to decide how accurate or revealing the questionnaire is about your preferred thinking styles. The aim is not to label or categorize you; the very last thing we should do is judge ourselves as being a type of thinker – or a type of person. The aim here is to identify where you might like to develop your abilities and become a more versatile problem-solver.

OK. Now mark the behaviours you think most obviously describe the way you like to solve problems. Take your time.

Circle all the phrases in each box that best describe your approach to dealing with problems.

Count up the number of behaviours you have marked in each column and transfer the number onto the grid below.

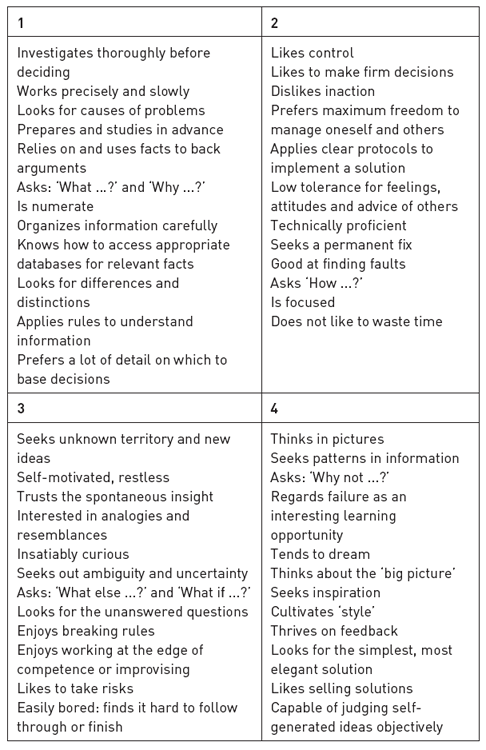

| 1: Analyst | 2: Engineer |

| My score: | My score: |

| 3: Explorer | 4: Designer |

| My score: | My score: |

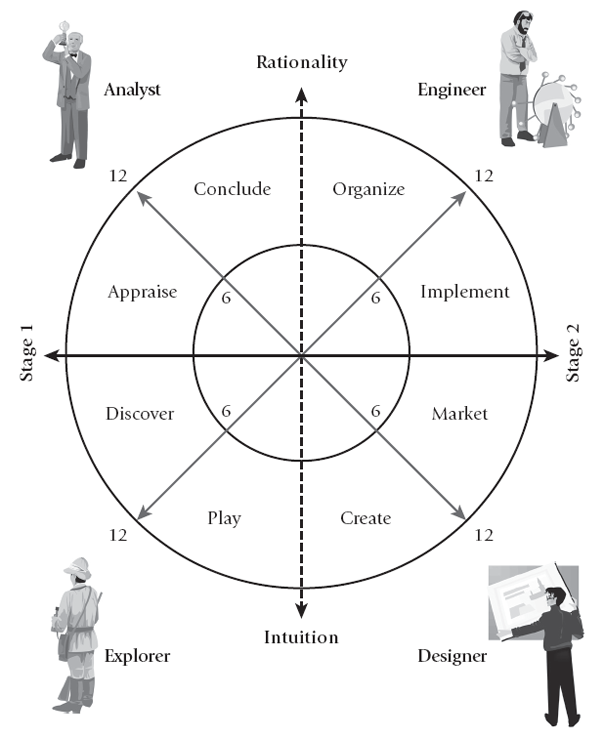

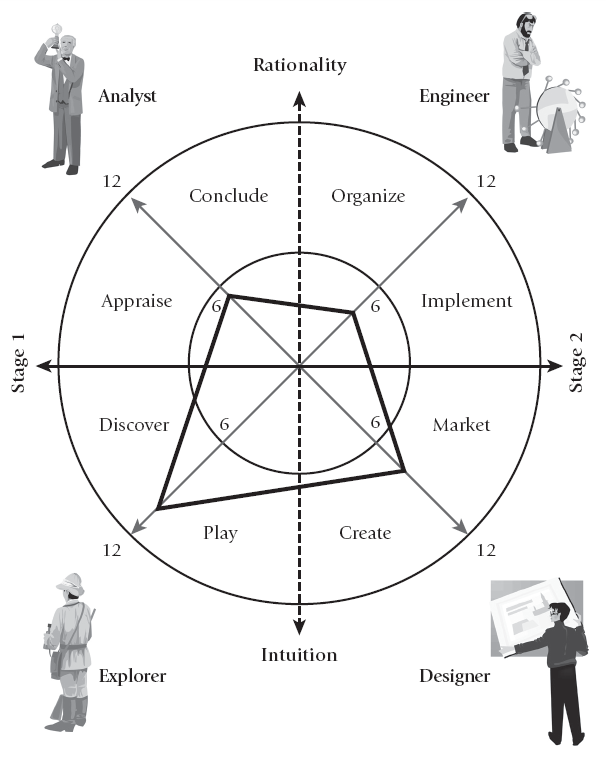

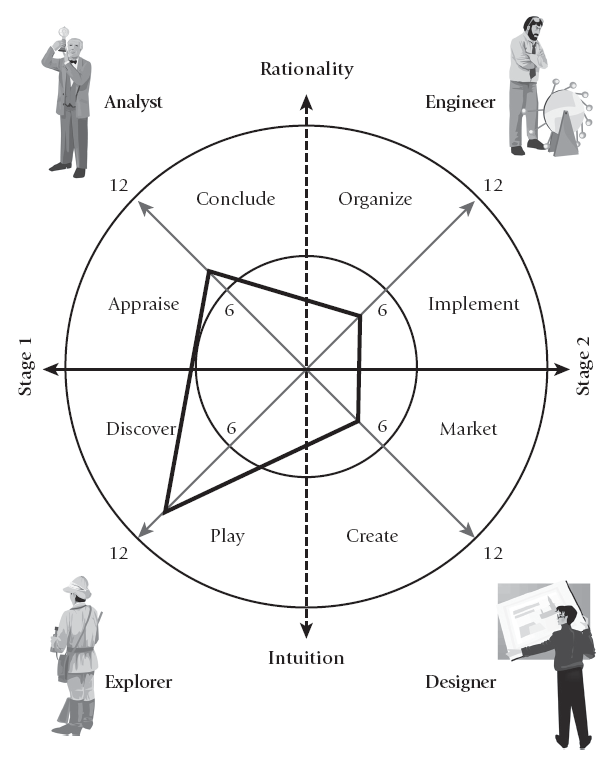

Now mark your scores on the target (see Figure 3.1). Mark the lowest scores nearest the centre of the target on each axis. I’ve added the numbers 6 and 12 on each axis to help you position your scores. Join the dots to create a four-sided shape, like the shape on Figure 3.4. Colour the shape, in whatever way you like. Go ahead, make your shape bold and interesting.

How the style profile works

Your problem-solving profile is based on two axes.

The two stages of problem-solving

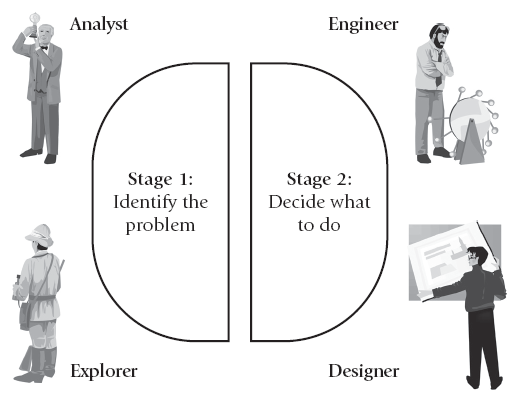

The horizontal axis represents the problem-solving process. The left-hand side of the axis represents Stage 1: identifying and describing problems. The right-hand side of the axis represents Stage 2: generating solutions.

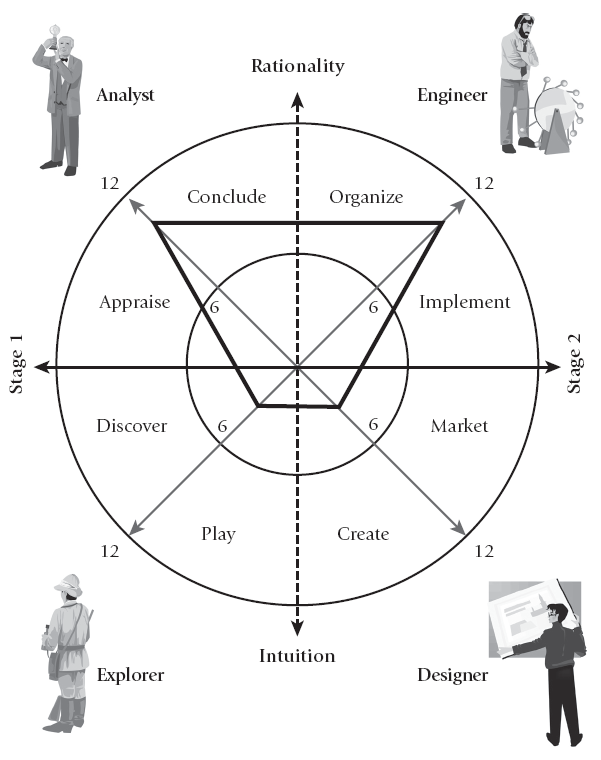

Two thinking styles relate to each of these stages (see Figure 3.2):

- Analyst and Explorer are the two styles of Stage 1 problem-solving: defining or describing problems.

- Engineer and Designer are the two styles of Stage 2 problem-solving: generating solutions.

Higher scores on the left side of the profile indicate that you prefer the investigative side of problem-solving to the implementation side. Others might see you as overly cautious, indecisive or unwilling to commit to action.

Figure 3.1 The target

Higher scores on the right of the profile might indicate that you prefer to implement rather than investigate. Others might see you as impetuous or impatient, taking action first and asking questions later.

Figure 3.2 Thinking styles linked to stages

Rationality and intuition

The vertical axis on Figure 3.1 represents the way you prefer to look at a problem situation (see Figure 3.3). At the top is rationality; at the bottom is intuition:

- At the top of the axis, you prefer to act rationally on your environment. You see reality as something to be encountered, explained and exploited. You are interested in how things are and how you want them to be. A gap in a problem is between what is and what should be.

Analyst and Engineer are the problem-solving styles relating to this view. - At the bottom end of the axis, you prefer to act intuitively with your environment. You see reality as something to be played with, and moulded. You’re interested in how things might be, and how you could reveal their potential. A gap in a problem is between what is and what could be.

Explorer and Designer are the problem-solving styles relating to this view.

Figure 3.3 The four styles

All problem-solving, of course, moves between all four styles. But many of us will prefer some aspects of problem-solving over others. Your scores suggest the styles that you’re most comfortable with.

Let’s look at each style in turn, and understand a little more about each.

The Explorer style [Stage 1: intuition]

![]()

Explorer is an investigative style. The essence of this style is searching (and researching). Explorer’s main assumption is that there is always more to find out.

The two key activities in Explorer are:

- discovering;

- playing.

Unlike the Analyst style, exploring is not about working out the truth but about discovering more. You have to know what’s around the next corner, beyond the next hilltop. You follow your nose (this is an intuitive style, after all). The Explorer style is curious: you’re constantly looking for new information and new ways of thinking about information. You like nothing better than the unexpected, the unconventional and the frankly unacceptable. You take what you’ve discovered and improvise with it. Forget formulae and accurate calculation; you love playing around, seeing what you can do with what you’ve discovered. You are always asking ‘What else?’, and ‘What if ...?’. The Explorer style loves challenging assumptions and reversing norms. You thrive on metaphors and resemblances.

Like Engineer, Explorer is risk-friendly. You’re easily bored; you are far more inclined to play than create a feasible solution.

What to do

Developing your Explorer style: questions to ask

- Where else can you look for ideas?

- How can you change your viewpoint?

- Where is opportunity knocking?

- What resources are in front of you?

- What ideas from history can help?

- Where can you ask: ‘What if ...?’

- What information may be lurking below the surface?

- Where does this information fit into a bigger picture?

- How can you change direction?

- How could you explore differently?

- Where haven’t you looked?

- What hunches have you got?

The Analyst style [Stage 1: rational]

![]()

Analyst, like Explorer, is an investigative style. The essence of this style is the desire to make sense of information and situations. Analyst’s main assumption is that understanding comes from applying reason to what we know.

The two key activities in Analyst mode are:

- appraising;

- concluding.

Analyst is rational. In Analyst mode you gather evidence, organize information and interpret according to formulae, rules or principles. You are good at spotting mistakes and faulty reasoning. In Analyst mode you probably prefer to work alone (although many researchers enjoy working in a team). You like nothing more than asking the Explorer style to find more data: the more, the better. You study the data, and restudy them, searching for the clues that will reveal the hidden truth.

This is a slow-paced style. Decision-making is difficult; you crave information that is complete, and research that is thorough. This is the most risk-averse of the problem-solving styles. People working in Engineer style may be urging you to sign off your results; you might see them as impatient and headstrong.

What to do

Developing your Analyst style: questions to ask

- How can you organize this information?

- Can you break this information down into smaller pieces?

- What’s the method?

- Is there a trend?

- What could you eliminate?

- What’s the real problem?

- What new rules could you use to organize this information?

- Can you test the idea?

- What variables can you alter?

- How do things fit together?

- Are there other categories?

- What can you measure?

The Engineer style [Stage 2: rational]

Engineer is an implementing style. The aim of the Engineer style is creating a solution that works.

Engineer’s two key activities are:

- organizing;

- implementing.

Engineer, like Analyst, is a rational style. It applies systems, protocols and routines to make things happen. In Engineer style you’re interested in how a solution works – and how to make it work better. Think of the word ‘engineer’ as a verb: to apply technical knowledge to practical problems (the kind of work done by a mechanical engineer or a civil engineer); and to bring about a solution through contrivance, skilful or artful (as in ‘she engineered a good result’). Engineer manipulates conditions and resources to bring about the required solution; this style is also interested in managing others to get results.

Unlike Analyst, Engineer tends to be fast-paced. Where Analyst craves accuracy, Engineer craves a workable solution. In your pursuit of a practical solution, you’ll do whatever is necessary: organizing resources, people and time to achieve the goal. Engineer is more tolerant of risk than Analyst – although you will always want to test your solution. In Engineer mode, information is only useful if it helps you construct your solution.

What to do

Developing your Engineer style: questions to ask

- Why won’t the solution work?

- What’s good about this solution?

- How does the solution fit into existing systems?

- Can you make the solution more effective or efficient?

- Can you implement the solution more effectively or efficiently?

- What will be the consequences of implementing this solution?

- Is the solution legally sound?

- Who do you need to help you implement the solution?

- Where will you find the resources to implement this solution?

- How will you measure the solution’s success?

- How could you improve the solution?

- Where’s the risk?

The Designer style [Stage 2: intuitive]

The Designer, like Explorer, is an implementing style. The essence of the Designer style is creating a solution that is neat, elegant or beautiful – something that others will find attractive and admirable.

The two key activities in Designer mode are:

- creating;

- marketing.

Designer is an intuitive style. Rather than seeing how a solution works, it’s interested in how it fits together. Designer’s aim is to find a solution that’s neat, elegant, beautiful. Designer delights in the process of creating a solution. Designer likes nothing better than to make complexity simple; you are looking for the pattern that will please the eye or the heart, even if the solution is impractical or ineffective (but, you will say, in good design, ‘form follows function’).

Designer thinks in pictures. You’re forever doodling. You are especially keen on the ‘big picture’, perhaps at the expense of detail, although you may quote Mies van der Rohe, the great architect, who said that ‘God is in the detail’. (You may well be rather fond of quoting.) You are drawn to an ideal vision of the future that may be unattainable: both the Analyst and the Engineer modes may need to rein in your imagination. You identify with your ideas, and love selling them to others. You welcome feedback, as long as it is fulsome praise. Criticism may not go down well.

Designer may well also want others to know about its creations. As you shift towards Engineer mode, you look for opportunities to market your creations; indeed, your main focus may be on creating an audience. Designer thrives on attention and praise.

What to do

Developing your Designer style: questions to ask

- What’s the neatest solution you can think of?

- Can you rearrange things?

- What can you substitute?

- What does this solution remind you of?

- How would the solution look reversed: inside out, back to front, inside out?

- How would a magician do it?

- What would a six-year-old child see in this solution?

- What rules can you break?

- How can you exaggerate the solution?

- If you were the solution, how would you feel?

- How will others judge the solution?

- How can you defend the solution?

Understanding your own problem-solving profile

Let me repeat this important point: this profile is not a personality test. It does not show, in any way, what kind of person you are. This profile shows where your strengths are likely to be when you’re solving problems.

It’s important to emphasize, too, that the way you scored yourself is not definitive. You might score differently on a different day, or in different circumstances. You might use your Explorer skills more frequently when managing people, for example, and your Analyst skills more when studying or managing a budget at work. You might use your Engineer skills more when leading a project, and your Designer skills when writing a proposal.

The profile may show, however, which skills you are most comfortable using.

Becoming a more versatile problem-solver

As well as helping us understand where we already work well as problem-solvers, this profile can show us hints about how we can develop our skills. The aim of the exercise, after all, is to become more versatile – so that we can tackle almost any problem!

Which is your most preferred style? (And your least?)

Let’s begin with individual styles. Each style brings its own particular strengths to problem-solving. A high score in one style suggests that you are something of an expert in that set of skills; similar scores in more than one style suggests that you are already a versatile problem-solver.

What to do

Examining your problem-solving profile: initial questions

Look at the profile you’ve drawn for yourself.

- Do you clearly excel in one style?

- Or are you equally proficient in more than one style?

- Is there one style that is definitely low in your own estimate of your abilities?

Now look at your lowest-scoring style. You may be able to find some very good reasons why you scored low, but the key question is: how could you develop that style to increase your versatility as a problem-solver?

Think about a situation in which you need to use that style. How could you go about developing that skill in order to solve that particular problem more effectively?

For example, I am not the most skilful of Analysts. I run my own business, and one area that has suffered as a result of my relative lack of strength as an Analyst is managing my accounts. I find it really hard to pay attention to detail, to remember the exceptions and cross-referencing, and all the other skills that help create an accurate, balanced set of accounts. So ‘doing the books’ has now become a deliberate development area. I enlist the help of my trusty accountant – who has designed excellent interactive spreadsheets for me – and I devote a certain amount of time each week to concentrated accounting work. I am slowly improving. But I am only doing so because I’ve chosen to and deliberately allocated time and mental resources to the task.

Looking at skills combinations

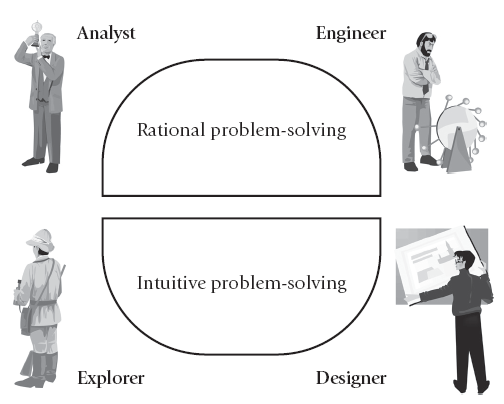

Effective problem-solving always involves a combination of styles. Solving a problem always means thinking at both Stage 1 and Stage 2. Intuitive problem-solving will tend to combine Explorer and Designer; rational problem-solving will tend to combine Analyst and Engineer. Really effective problem-solving will exploit the strengths of all four styles.

Two particular sets of combinations are worth thinking about.

First, the quality of our work at Stage 2 – when we’re implementing a solution – depends directly on the quality of our work at Stage 1, when we’re identifying the problem. Too little use of Analyst skills, for example, may mean that we’re working with inaccurate information or faulty reasoning. Too little use of Explorer skills, on the other hand, may mean that we’re seeking to solve a problem with too little information or analysis.

To see whether you favour Stage 1 or Stage 2, ask: does my profile sit more on the left or the right of the diagram?

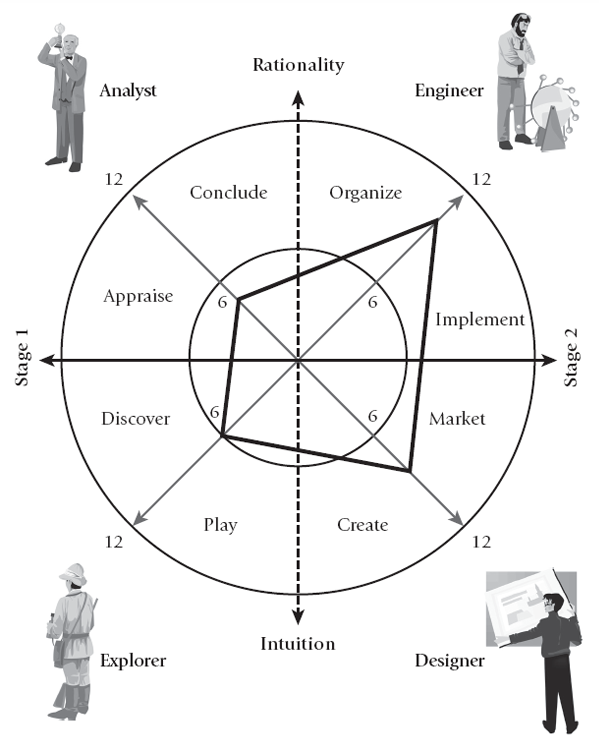

For example, Figure 3.4 shows a profile that is quite strongly weighted towards Stage 2 problem-solving. This profile might suggest that the subject favours implementing solutions over understanding problems. More attention to Stage 1 problem-solving might help them develop more accurate and robust information on which to act.

Figure 3.4 Sample profile: weighted towards Stage 2 problem-solving

Figure 3.5, by contrast, is a profile weighted towards Stage 1 problem-solving. This profile – particularly its emphasis on Explorer – suggests that the owner might benefit from more implementation skills: setting deadlines, testing ideas for feasibility, forcing themselves to make decisions.

Figure 3.5 Sample profile: weighted towards Stage 1 problem-solving

Secondly, rationality is never divorced entirely from intuition. The skills of rational problem-solving – Analyst and Engineer skills – always operate on the back of the skills of intuitive problem-solving (Explorer and Designer). That’s why I’ve put rationality above intuition in the diagram illustrating the four styles (see p. 63). Rational thinking always works with assumptions; in fact, it’s not possible to think at all without making assumptions. Rational analysis always works with a selection of the information available to it; and it’s intuition, more often than not, that made the selection.

Intuition can act without rationality (as we shall see, in the next chapter); but rationality can never act without some prior intuitive input.

To see whether your profile prefers intuition or rationality, ask: does my profile sit towards the top or the bottom of the diagram?

Figure 3.6 shows a profile weighted towards the intuitive. This profile suggests that its owner might need to develop more rational problem-solving skills: the skills of reasoning, argumentation and practical implementation that are represented by the top half of the profile.

By contrast, the profile in Figure 3.7 is weighted clearly towards rationality. The owner of this profile might benefit from working on some of the skills of intuitive problem-solving: exploring a little more, perhaps, and thinking more about the elegance of a solution than just its accuracy or practicality.

The virtues of versatility

Becoming a more versatile problem-solver means developing our skills, not becoming a different person. Versatility is a measure of our willingness and ability to change our behaviour, based on the needs of the situation or relationship at a particular time. Adapting your behaviour doesn’t mean changing your personality.

You can choose which skills you want to develop. We often adapt our behaviour unconsciously, if the stakes aren’t too high for us. We might be able to adapt easily to one problem, but not to another. We can test our ability to develop new problem-solving skills in situations where we may not want to adapt, but where we do choose to adapt.

Figure 3.6 Sample profile: weighted towards the intuitive

No one style is naturally more versatile than another. Versatility may mean slowing down, or using more of the Analytical or Designer skills. It may mean moving more quickly into Explorer or Engineer mode. Analyst and Engineer usually benefit from developing interpersonal skills, and building relationships with others. Explorer and Designer often benefit from developing the more systematic skills of Analyst or Engineer.

Figure 3.7 Sample profile: weighted towards rationality

It’s easier to be versatile in some situations than in others. We often use one style in our professional lives and a different style in our personal or social lives. We may find ourselves less versatile when we’re trying to solve problems with people we know well.

We need to decide how versatile we want to be. The temporary stress of using a ‘foreign’ problem-solving style may be worth it for the sake of improved results. Working a long way outside our comfort zone, however, may actually harm our effectiveness and do us little good. It’s worth choosing our experiments in new problem-solving styles with some care.

There’s no doubt, though, that by becoming more versatile problem-solvers, we increase our effectiveness generally. We can take more control over the issues that affect us, and increase our power to influence events. We can take fuller ownership of the problems we encounter.

And problem ownership is what we’ll explore in the next chapter.

In brief

Becoming a better problem-solver means becoming more versatile.

We can identify four broad problem-solving styles:

- Analyst

- Explorer

- Engineer

- Designer.

Analyst and Explorer are the two styles of Stage 1 problem-solving: defining or describing problems.

Engineer and Designer are the two styles of Stage 2 problem-solving: generating solutions.

Analyst and Engineer are more rational styles, which tend to act on a situation.

Explorer and Designer are more intuitive styles, which tend to act with a situation.

Explorer’s two key activities are discovering and playing.

Analyst’s two key activities are appraising and concluding.

Engineer’s two key activities are organizing and implementing.

Designer’s two key activities are creating and marketing.

We can become more versatile by focusing on the styles that we’re least comfortable with. We can explore whether we’re more comfortable with intuitive or rational styles, and by understanding whether we favour Stage 1 or Stage 2 thinking. By developing different styles, we can become more versatile and more effective problem-solvers.