Read this story all the way through, at least once, and then answer the questions.

An oil well in the Arabian desert exploded. The oil company was faced with an inferno consuming vast quantities of oil every day. All efforts to extinguish the fire failed. Eventually, the company called in Flash Quencher, the famed fire-fighter.

Flash could see that the way to quench the fire was to dump a huge quantity of fire-retardant foam at the base of the well. Although there was sufficient foam on site to do the job, the company didn’t have a hose large enough to deliver the foam quickly enough. The small hoses on site were simply inadequate.

Flash knew what to do. He stationed men in a circle around the well, each with a hose. All the hoses were opened up at once, and foam was directed at the fire from all sides. The blaze was put out and Flash earned $3 million.

Does this story describe a presented problem or a constructed problem?

Is the problem well structured or ill structured?

List the:

- initial conditions;

- goal conditions;

- operators; and

- constraints.

A dream is an ill-structured constructed problem. It’s expressed exactly like a plan: as a ‘how to’ statement. Unlike a plan, however, a dream solution is not well defined. Indeed, we may not be able to define the problem itself clearly. We may not know exactly where we are, or where we want to go. We may not have any idea how to create our dream: the operators are unclear. We may feel all sorts of constraints: budget, resources, time, regulations. And other constraints may be at work, of which we are unaware: unchallenged assumptions about how things work, how to get results, ‘how we do things around here’.

Dreams: key features

- Problem statement: ‘How to ...’

- There is a gap between what is and what could be.

- Problem ill structured: initial conditions, goal conditions, operators and/or constraints unclear.

- Solution: create something new.

- Leading heuristics: ‘how to’; associative thinking; metaphor; reversal.

Typical examples of dream problems might be:

- How to make our products more attractive to our customers.

- How to invent a new, healthy fast-food recipe.

- How to get on better with a problematic colleague.

- How to be more successful.

To tackle a dream ‘how to’, we have to find new ways of thinking about it. The aim is not to see the ‘how to’ more clearly, but to see it differently. In other words, we need to be able to reframe. (We investigated reframing in Chapter 1.)

Dreams: what styles to use?

Dreams demand the kind of thinking that generates new ideas. Call it ‘creative thinking’.

Making dreams come true demands a combination of Explorer and Designer skills.

What to do

Six steps towards being more creative

Based on a number of studies, creativity seems to be a combination of six competencies. Develop your skills in these areas and see yourself become more creative.

![]()

Look for problems. Find the unanswered questions, the most awkward problems, the toughest conundrum and the next challenge. Develop your love of research and your hunger for information.

Become mentally mobile. Find different ways of looking at situations. Become adept at turning ideas inside out or back to front. Ask ‘What if?’. Challenge assumptions. Fall in love with metaphors. Look for the unusual way to describe a problem.

Take risks. Live a little more dangerously. Look for excitement and stimulation. Seek out unknown territory. Lower your boredom threshold. Improvise. Learn to love failure. Find the edge of your competence and try to live there more often.

Develop a personal aesthetic. Look for patterns, associations and resemblances. Take complexity and try to simplify it. Become comfortable with ambiguity, asymmetry and uncertainty.

Be objective about your own work. Ask others to critique your work and integrate their thoughts into your future efforts. Become hungry for feedback.

Do what motivates you for its own sake. Choose the tasks that arouse your passion. Forget rewards, salary or perks.Become impatient of supervision.

We associate creativity with inspiration and genius: factors that are difficult to replicate or to learn. But creative thinking is as organized as any other kind of thinking. We can learn to do it, and we can use it to generate real and useful solutions. In this chapter, we’ll discover how.

Mindsets: the good news and the bad news

As we’ve seen throughout this book, our brains use mental models to explore the world. We assimilate new information to the mental models that have worked in the past, adjusting them occasionally and applying them in new situations to get results. The mental models that work well for us become stronger; the mental models that are less successful become weaker or disappear.

The strongest mental models become mindsets.

Mindsets are an essential part of thinking. They create the assumptions without which thinking wouldn’t be possible. They create the routines, protocols and procedures by which we do most of what we do. Without mindsets, we wouldn’t be able to get through a day; each operational task would become a new problem, and we would be overwhelmed with potential solutions.

The power of mindsets: part one

Take a moment to count the number of pieces of clothing you put on this morning. Include jewellery, watches and other accessories. (Pairs count as one.) How many possible ways are there of putting on your clothes? (The answer is on page 216.) How many did you consider before starting to get dressed this morning?

The danger with mindsets is that they limit our ability to reframe. Mindsets tell us what to look for, what to see, how to interpret it and what to do. If information fails to fit the mindset, we’re more likely to question or reject the information than to question the mindset. We may not even see the information.

You walk into a crowded bar, search desperately for an empty seat, find one and sit down. Two minutes later your friends make their way to your table and ask why on earth you ignored them. They were waving frantically, but you ignored them completely. The mindset of looking for a free seat blinded you – literally – to their attention-seeking gestures.

The most well-known study demonstrating the power of mindsets to blind us to information was conducted in the late 1990s by Daniel Simons of the University of Illinois and Christopher Chabris of Harvard University. They asked subjects to watch a short video in which two groups of people pass a basketball around. The subjects were told to count the number of bounce passes and aerial passes between team members. After watching the video, the subjects were asked if they’d noticed anything unusual. About half the subjects had failed to spot a woman wearing a full gorilla suit crossing the field of view. (Another version involves a woman carrying an umbrella.) The mindset established by the task – carefully counting ball passes – had completely blinded these people to the unusual event in front of their eyes.

Because mindsets so powerfully frame the way we see reality, they can severely constrain our ability to solve problems where reframing is needed.

Danger! Mindsets at work!

Mindsets are at work continuously. By focusing on the mental models that govern how we operate, we risk missing the opportunities to discover new solutions. Here are some obvious examples:

- Product development: focus on engineering the product rather than looking for different ways of satisfying the customer.

- Introducing new IT systems: designing on the basis of existing IT solutions rather than defining user requirements and designing to satisfy them.

- Contractual negotiations: discussing preconceived ‘issues’ rather than addressing the assumptions on both sides about what the issues might be and how they have arisen.

- Responding to customer complaints: regarding the complaint as ‘something to be dealt with’ rather than an opportunity to improve a product or service.

- Quality management: looking for defects rather than building in quality.

- Strategy: ‘re-engineering’ an organizational structure rather than asking ‘What business are we in?’.

Operational thinking and creative thinking

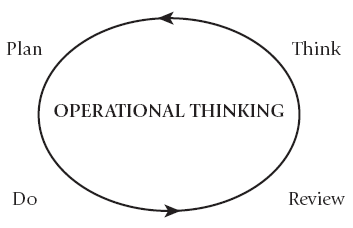

We spend most of our active time in a cycle of doing, evaluating, reflecting, planning and re-doing (see Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 The operational cycle

As we travel the operational cycle, we use protocols, procedures and routines: mindsets that regulate our behaviour. They help us to work efficiently; they help us to improve our processes and to use resources well.

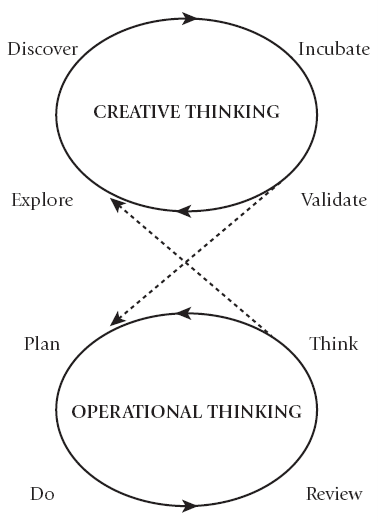

But when we are looking for new ideas, these routines become limiting frames on our thinking. We need to reframe in order to explore new possibilities. We need to leave the operational cycle and cross into the creative cycle (see figure below).

Figure 9.2 Crossing into the creative cycle

These two cycles have radically different aims. The aim of the operational cycle is to improve what we do. The aim of the creative cycle is to find something different to do. The principal thinking styles in the operational cycle are to:

- plan;

- act (to carry out the plan);

- review what we’ve done;

- think about what the review has told us; and

- adjust the plan so that future action is improved.

The principal thinking styles in the creative cycle are to:

- explore;

- discover;

- incubate (think about what we’ve discovered); and

- validate (develop what we’ve discovered into something useful).

Joseph Campbell, the great mythographer, once defined creativity as ‘going out to find the thing society hasn’t found yet’. The creative cycle is the process of discovering something new and useful that we can bring back into the operational cycle.

Most of us think and work in the creative thinking cycle only occasionally. It’s unlikely that any of us would think ‘outside the box’ as a matter of course (unless our operational work demanded it of us – as designers, performers or scientists, perhaps). Indeed, there are usually only two circumstances in which we’ll cross from the operational cycle into the creative cycle:

- because we have to; or

- because we choose to.

It may take a crisis to force us to move into creative thinking. If a relationship is in danger of collapsing, we might have to reframe our assumptions about it. If a company is facing bankruptcy, we may have to come up with creative solutions for keeping the enterprise afloat or to reinvent it. Unfortunately, crises tend to be emotionally fraught and thus not always the best time to engage in creative thinking.

But we can always choose to leave the operational cycle behind for a while and do some creative thinking. We can engage in thought experiments; we can run brainstorming sessions; we can run a research project or a pilot.

To cross successfully into the creative cycle, we need to be relaxed and safe. We need to be in a place where we can feel free to think the unthinkable, and where we can manage risk. Airline pilots wouldn’t try out new ways of controlling a plane while actually flying a jet; they’d use a flight simulator. Similarly, if we want to generate new ideas, we need a ‘flight simulator’ – a secure environment where we can break the rules safely.

The two cycles – operational and creative – are separate. We can’t do creative thinking in the operational cycle, and operational thinking is unhelpful in the creative cycle. One of the greatest dangers in thinking about dreams is that we may find ourselves trying to think in both cycles at the same time. The classic symptom of trying to think in both cycles simultaneously is the emergence of ‘idea killers’ – operational responses to new ideas generated by creative thinking.

What to do

20 idea killers

Listen out for these responses when you’re trying to generate new ideas. They are key signs that you are slipping back into the operational cycle.

Not practical.

It’ll never work.

Let’s wait a bit.

Too complicated.

What’s the point?

That reminds me ...

It’ll cost too much.

It’ll never catch on.

What about the intangibles?

You haven’t thought it through.

We tried it before and it didn’t work.

That’s a bit too radical for this company.

You’ll never get people to change their ways.

I like the idea, but I’m not sure that my boss ...

That isn’t quite the way we do things around here.

The idea isn’t relevant to our current strategic planning.

Good idea. We shall appoint a working party to look into it.

Of course, that’s just the sort of idea we might expect from you.

Hm. Now, suppose we changed this little bit, and that little bit, and ...

We don’t have the resources/staff/money/time/expertise/ room/systems ...

Intuition revisited: training to reframe

Most reframing happens unconsciously. Remember the Rubin vase in Chapter 1 (see page 18)? Most of us can reframe that image with no effort, and without consciously thinking about it.

Because reframing is usually unconscious, we might feel that we can do little to develop it as a conscious skill. Someone might jolt us into reframing a problem – by asking us ‘to look at it another way’ or shouting at us to ‘look at it from my point of view – for a change!’.

Roger van Oech, creativity consultant and author, calls these moments ‘whacks on the side of the head’. We can look for more opportunities to give ourselves whacks on the side of the head; and, in fact, there’s a lot more we can do to help our intuitive mind to reframe more efficiently.

The first skill we can develop is the ability to prepare ourselves for those moments when reframing might occur.

Archimedes in the bath

The most famous story of intuitive problem-solving is the tale of Archimedes in the bath.

Archimedes of Syracuse (c 287BC – c 212BC) was one of the leading scientists of antiquity. According to Vitruvius (a Roman writing 200 years later), King Hiero II of Syracuse had donated pure gold to make a votive crown for a temple in the city. The king suspected that a rogue goldsmith had adulterated the gold with silver, and asked Archimedes to find out if the crown was indeed pure gold.

Thinking about the problem, Archimedes transformed it. Impure gold has a lower density than pure gold. Density is weight per unit volume. Archimedes knew the density of pure gold, and he could easily weigh the crown. All he needed to know was its volume.

But calculating the volume of an intricately irregular solid like a crown was no easy task. There was no way he could melt the crown down into a regular shape.

Archimedes was stuck.

So, like any good thinker, he took a break and visited the local baths. As he sank into the warm, relaxing water, he noticed that his own irregularly shaped body displaced its own volume of water – and he could do the same with the crown to measure its volume. Divide the crown’s weight by its volume, and Archimedes would find the metal’s density. Problem solved.

So excited was Archimedes by this discovery that he leapt from his bath and ran through the streets naked, crying ‘Eureka!’ (which is Greek for ‘I’ve found it!’).

And apparently the goldsmith had indeed added silver to the gold. Good news for Archimedes; bad news for the goldsmith.

The four stages of reframing

Over 2000 years after Archimedes, a socialist and educationalist called Graham Wallas formalized reframing into a four-part model:

- Preparation (conscious work on a problem).

- Incubation (internalization of the problem context and goals into the subconscious, where the problem is processed).

- Illumination (when reframing occurs: the ‘eureka’ moment).

- Verification and elaboration (checking that the insight is valid and then developing it into a workable solution).

Wallas’s model suggests that reframing is more likely to happen when our conscious, rational minds are relaxed.

How good are you at reframing?

Here’s a problem that needs a creative solution. Study the problem carefully and then see if any possible solution occurs to you.

You’re a doctor with a patient who has a malignant stomach tumour. Unless you can destroy the tumour, the patient will die. You have at your disposal a kind of ray that you can use to destroy the tumour, if the rays hit the tumour at a sufficiently high intensity. Unfortunately, at the required intensity the rays will also destroy any healthy tissue they pass through. At lower intensities the rays are harmless to healthy tissue but will not affect the tumour. What type of procedure could you use to destroy the tumour with the rays, without destroying the healthy tissue?

If you have immediately solved the problem, well done! If not, let me give you some instructions.

First, express the problem as a ‘how to’ statement. How well structured is the problem in the form in which you’ve expressed it? Initial conditions and goal conditions are both clear: the presence and absence of the tumour, respectively. The lack of structure seems to arise with operators: how many ways can you think of to use the rays?

If you have solved the problem by this point, well done. If not, let me give you a hint.

Is there anything that you’ve read so far in this chapter that might help you solve this problem?

And if that hasn’t nudged your thinking, let me try a hefty whack on the side of your head.

Could you use the oil well problem at the start of this chapter to help you?

At some point in the last few lines, I hope you’ve had a ‘eureka’ moment. You suddenly realized that the Flash Quencher story could supply the solution to the tumour problem: where Flash used hoses in a circular arrangement to focus low amounts of foam on one point, you could administer low-density rays from different directions to destroy the tumour without damaging the surrounding tissue.

You’ve reframed: the same principle, in different contexts, has helped you to solve the problem.

Put another way, the oil well story has become a metaphor for the tumour problem. (More about metaphors shortly.)

Now: did you reframe without a hint from me? If you did, then I salute your powers of intuition. When Mary Gick and Keith Holyoak conducted a very similar experiment in the late 1970s, they found that fewer than 10% of their volunteers used the story to solve the problem without a hint. Given a hint by the research team, however, 75% successfully reframed.

Life, of course, tends not to give us hints. Without guidance, we might never make the new connections that allow us to reframe a problem. Are we condemned, then, to simply wait for the moments when reframing happens? How can we train ourselves to reframe a bit more systematically?

As the great sci-fi writer Philip K. Dick said: ‘Look where you least expect to find it.’ It sounds paradoxical: how can we look for the unexpected? Or rather: when do we look for the unexpected?

When we explore. When we go on holiday, on an excursion, on an expedition into the unknown. Exploration is the systematic search for the unexpected. If you go where you’ve already been, you’ll find what you’ve already found. To find something truly new: explore. That’s why the first step on the creative cycle is to explore.

And there are techniques available to help us do just that.

Associative thinking

Reframing techniques have gone by various names over the years. The basic term is ‘associative thinking’. We link items in our minds by making associations with them: perhaps because they are similar, because they are closely linked, or because they are opposites. It’s easy to do, and it can be more useful than you might think, especially in pursuit of dream solutions. Reframing creates new and unexpected associations, which are the ‘creative sparks’ of new ideas.

Making the links: a mental diversion

We can link items in our minds in three ways (for the moment!):

- similarity;

- closeness;

- opposition.

For example, we might link the word ‘apple’ to:

- orange (similar);

- tree (closeness); or

- poison (opposition: I’m thinking of Snow White, fooled by the wicked queen’s poisoned apple).

Sometimes, one kind of link is easier to find than another. (What’s the opposite of an apple?) That doesn’t really matter. Associative thinking is not concerned with finding the right answer. (And, in that respect, it’s the opposite of rational thinking, with its curse of the right answer.) Any answer that makes a new link is acceptable when we’re thinking associatively. The only rule is that we should try to look for surprising links (that paradox, again): the more surprising the link, the greater the likelihood of reframing.

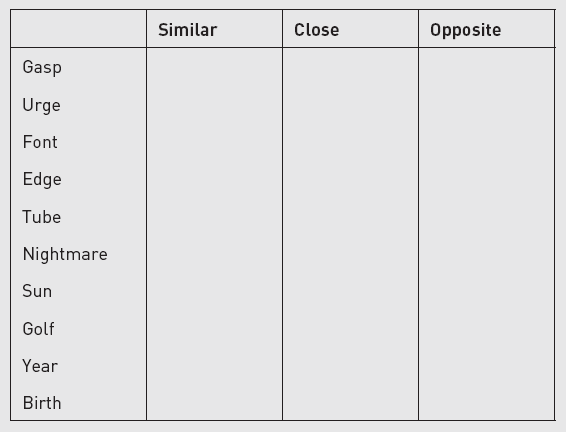

Making the link: exercising your powers of associative thinking

Here are some more words, chosen at random. Can you create some associative links?

Most creativity techniques involve associative thinking in pursuit of reframing. Broadly, they fall into two categories: techniques involving metaphor (looking for similarities and closeness); and techniques involving reversal (looking for opposites).

Metaphor: what you see is – something else

What have the following all got in common?

An industry watchdog

The University of Life

A hive of activity

Cashflow

A ribbon development

A cast-iron guarantee

The answer, of course, is that they are all metaphors. A metaphor reframes instantly: it allows us to see something in terms of something else. By describing a nation state as a ship, or a financial instrument in terms of heavy engineering, we can look at these things differently.

We’ve long realized how important metaphor is in solving problems. Stephen Mithen, whom we met in Chapter 2, sees metaphor as key to the cognitive fluidity that opens up the cathedral of the human mind. Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset calls metaphor ‘probably the most fertile power possessed by men’. Metaphor is certainly one of the core tools of creative thinking.

I remember, on my first trip to Crete, seeing the word on a sign at the airport: μεταθοραι (metaphorai), meaning ‘transport’; and then, a few minutes later, on the side of a lorry (meaning ‘logistics’). Greece: the land where metaphors roam the streets!

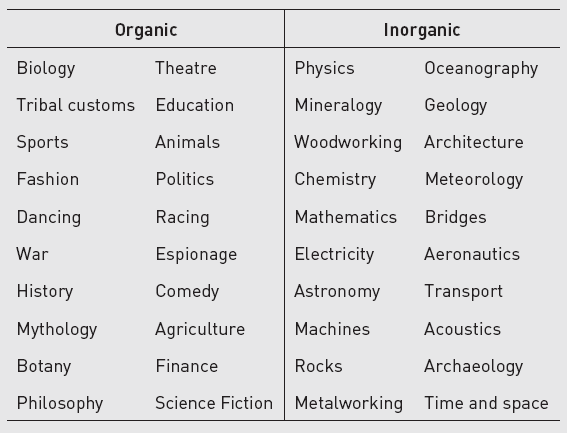

New worlds: finding unusual metaphors to work with

One way to make our thinking more metaphorical is to place a problem in a different world. We might categorize these worlds broadly as ‘organic’ and ‘inorganic’. If the problem is ‘organic’ – if it involves people, for example, or biological systems – we can invoke a metaphor from the inorganic world (suppose our organization were a galaxy of stars?). If the problem is technical, we could find an organic metaphor (what if an airline catering trolley were an animal?).

Switching radically between worlds can provide more interesting and provocative metaphors.

Consulting the oracle: metaphors at work

An oracle is a metaphor-making tool. Oracles use randomly generated information to help us think associatively. They invite us to look at an idea in terms of something else. We’re unlikely to make new mental connections using our existing mental models and memories; we need randomly generated information to help us make new links, reframe and find new ideas.

We love oracles. We read our horoscopes. We shuffle Tarot cards and throw dice. In ancient times, people visited oracles in places such as Delphi, where priests or priestesses would utter strange pronouncements in answer to their questions.

What to do

A do-it-yourself oracle

The easiest way to make your own oracle is to use randomly generated words. Key the phrase ‘random word generator’ into your search engine and you’ll soon find one. The generator will offer you randomly selected words that you can juxtapose against a problem to stimulate new ideas.

For example, suppose the problem is:

How to encourage my team to be more creative

I generated four words on a random word generator:

- Salon: how about establishing a creativity salon or room, where the team can use toys and games to stimulate new ideas?

- Curry: how about finding ways of mixing different ingredients into projects or team activities to spark creativity?

- Captain: does the team need leadership to help it unlock its creativity?

- Roof: maybe we need an overarching strategy that integrates creativity into team objectives and competencies.

The best words for this kind of associative thinking are concrete nouns: words that name things physically present in the world. Concrete nouns stimulate our imagination with images, and the images create powerful sparks. Words like ‘finance’, ‘planning’ or ‘region’ are not likely to be so rich in associations.

The intermediate impossible: reversal as an idea generator

A second set of techniques uses the idea of reversal to give our thinking a nudge.

Reversal means turning a problem inside out, upside down or back to front. The idea is that, if we deliberately imagine the direct opposite of what we want to achieve, we may find new ways of looking at it.

For example, if we were considering ‘how to improve customer satisfaction with our helpline’, we might start to generate new ‘how to’ statements that are deliberately the reverse of what we want to achieve:

- How to reduce customer satisfaction with our helpline.

- How to enrage our customers.

- How to scare our customers.

- How to chase our customers away with no solution.

- How to be as unhelpful as possible.

And so on.

Such crazy ideas may hold within them the seeds of a new, useful idea. For example:

- How to reduce customer satisfaction with our helpline: how about giving customers more information so that they need to ring the helpline less?

- How to enrage our customers: how about finding the key sources of dissatisfaction when customers call the helpline, and train helpline staff to identify them; how about improving our anger management techniques?

- How to scare our customers: how about explaining more clearly to customers the consequences of doing something wrong?

- How to chase our customers away with no solution: how about giving customers more tools to solve their own problems?

- How to be as unhelpful as possible: how about focusing more on the diagnostic stage of a customer call, before leaping to suggestions for help?

People sometimes find reversal techniques harder to use than metaphorical ones. Reversal challenges our deepest assumptions, and that can be uncomfortable. However, with practice, reversal can be great fun. Thinking up the most outrageous negative ideas can become a competitive game (the key to winning, in my experience, is to think up an idea that offends the rules of physics). The aim of the technique is to find what Edward de Bono calls ‘intermediate impossibles’: ideas that are as impossible as we can make them, which can act as intermediate stages on the lateral journey from problem to new idea.

The power of mindsets: part two

How many possible ways are there of putting on your clothes? (We asked this question on page 201).

The answer is simply the multiple of all the numbers up to your chosen number of pieces of clothing.

For example, if you put on eight pieces of clothing this morning, the number of possible ways of getting dressed is:

8 × 7 × 6 × 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1 = 40,320

Of course, some operations are not allowable: we don’t usually put on socks over shoes or underwear over trousers or skirts. But even a tenth of the number presents a formidable array of options. The mindset we develop over the years helps us to ignore all the possibilities. Without it, we’d still be wondering how to get dressed at bedtime.

In brief

Dreams: key features

- Problem statement: ‘How to ...’

- There is a gap between what is and what could be.

- Problem ill structured: initial conditions, goal conditions, operators and/or constraints unclear.

- Solution: create something new.

- Leading heuristics: ‘how to’; associative thinking; metaphor; reversal.

Dreams demand creative thinking. Creative thinking breaks mindsets (the mental models that create the assumptions without which thinking wouldn’t be possible). Mindsets help operational thinking, but they are a powerful constraint on creative thinking.

To think creatively, we need to leave the operational cycle and cross into the creative cycle. The aim of the operational cycle is to improve what we do. The aim of the creative cycle is to find something different to do. We only cross into the creative cycle because we have to, or because we choose to.

Creative thinking involves reframing: seeing the same element of reality through a different mental model. The reframing process has been codified into four stages:

- preparation (conscious work on a problem);

- incubation;

- illumination;

- verification and elaboration.

Reframing uses associative thinking. We can create associations in terms of:

- similarity;

- closeness;

- opposition.

Most creativity techniques use associative thinking. Broadly, they fall into two categories: techniques involving metaphor (looking for similarities and closeness); and techniques involving reversal.