6 Forces Inside Us as Inhibitors

In order to fully understand the role of Humble Inquiry as a means of building a positive relationship, we have to examine further the complexity of communication. We have to understand how the rules that culture teaches us as to what is and is not appropriate to ask or to tell in a given situation influences our internal communication process. As I have pointed out, being a responsible member of society means the acceptance of the rules of how to deal with each other and how to conduct conversations which show reciprocation, equity, and acceptance of each other’s claimed value. When we don’t get acknowledgment or feel that we are giving more than we are getting out of conversations or feel talked down to, we become anxious, disrespected, and humiliated. Humble Inquiry should be a reliable way to avoid these negative results in a conversation. So why don’t we do it more routinely?

One answer is that sometimes we don’t want to build a positive relationship; we want to be one up and win. Sometimes we are tempted to use Humble Inquiry as a ploy to draw the other person out in order to gain advantage, but, as we will see, it is a dangerous ploy because we are likely to be sending mixed signals, and our lack of sincerity may come through. In that instance, we will actually weaken the relationship and create distrust.

A second reason is that there are in all cultures specific rules about what it is not OK to ask and/or talk about in any given situation, which requires caution as we try to personalize relationships through Humble Inquiry. Such caution escalates when we are conversing with people from other cultures and if we are trying to decipher what is appropriate openness with respect to authority and trust building. In this chapter I first present an interpersonal model that explores this issue and explains why we send mixed signals, why insincere Humble Inquiry does damage, why interpersonal feedback is so complicated, and how Humble Inquiry can avoid some of these difficulties. Later in the chapter we look at an intrapersonal model that explains why so often even well-intentioned Humble Inquiry goes awry and why it is actually difficult to access our ignorance, to ask questions to which we truly don’t know the answer.

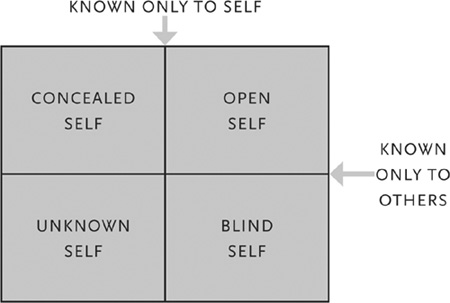

The Johari Window: Four Parts of Our Socio-Psychological Self

The Johari window is a useful simplification first invented by Joe Luft and Harry Ingham to explain the complexity of communication.11 We each enter every situation or budding relationship with a culturally defined open self—the topics that we are willing to talk about and know are OK to talk about with strangers—the weather, where you are from, “name, rank, and serial number,” and task-related information. We have all learned what is appropriate in a given situation. What we talk about with a sales clerk and what we talk about with a stranger at a party are different but quite circumscribed by the culture. We also develop clear criteria of what is personal and what is not.

As we converse with others, we send a variety of signals above and beyond the intentional ones that come from our open self. Our body language, our tone of voice, our timing and cadence of speech, our clothing and accoutrements, our work with our eyes all convey something to the other person, who forms a total impression of us based on all of the data coming from us. Much of this information is passed without our being aware of it, so we must acknowledge that we also have a blind self, the signals we are sending without being aware that we are sending them, which nevertheless create the impression that others have of us.

The four parts of the self

One of the ironies of social life is that such impressions can be the subject of gossip about us by others but may never be revealed to us. We know that we form impressions of others, so must know that they form impressions of us, but, unless we create special circumstances that bend some of the rules of culture, we may go through an entire lifetime without ever finding out what some others really thought of us. This insight introduces us to our concealed self—all the things we know about ourselves and others but are not supposed to reveal because it might offend or hurt others or might be too embarrassing to ourselves.

Things we conceal from others are insecurities that we are ashamed to admit, feelings and impulses we consider to be anti-social or inconsistent with our self-image, memories of events where we failed or performed badly against our own standards, and, most important, reactions to other people that we judge would be impolite or hurtful to reveal to their face.

We realize that in a relationship-building process the most difficult issue is how far to go in revealing something that normally we would conceal, knowing at the same time that unless we open up more, we cannot build the relationship. When such opening up is formatted, as in special workshops or meetings designed for the purpose, we label this category of communication feedback. The contortions we go through to get feedback mirror the cultural restrictions on not telling others face to face what we really think of them. The reluctance we display when someone asks us for feedback mirrors the degree to which we are afraid to offend or humiliate. We duck the issue by trying to emphasize positive feedback, knowing full well that what we really are dying to hear from others is where they see us as wanting or imperfect, so that we can improve. We see all our own imperfections because our concealed self is filled with self-doubt and self-criticism, and we wonder whether others perceive the same flaws. And, of course, they do, but they would not for the world tell us, in part because that would license us to tell them about their flaws, and we would then both lose our self-esteem.

Asking about and revealing something that is personal are ways we break out of this cultural straitjacket. We can drop the professional task-oriented self and either ask about or reveal something that clearly has nothing to do with the task situation but that invites acknowledgment and a more personal response. In that sense, Humble Inquiry can begin with something we reveal about ourselves, as a prelude to asking about that area in the other. I can choose to tell something to the other that reveals Here-and-now Humility and thus opens the door to personalizing the conversation. Dr. Brown can tell his team over lunch how much he enjoys fishing in the Scottish Highlands, and Dr. Tanaka can reveal his passion for golf. They can then joke about the tough work schedule and how it prevents them from ever getting any food better than what the hospital cafeteria offers.

If these early revelations and questions are acknowledged and reciprocated, the relationship develops and allows “going deeper.” But it has to be a slow and carefully calibrated process. Recall the New Yorker cartoon where a blustery boss says to his subordinate, “I want you to tell me exactly what you think of me … even if it costs you your job.” In other words, a great deal can be exchanged before the relationship gets to the personal feedback stage, and even then it probably works best if it stays on task-related matters. Personal feedback remains dangerous even in an intimate relationship.

In a relationship across hierarchical boundaries it may be necessary for the higher status person to start humble inquiry not with a bunch of personal questions to his team but with a revelation about himself as in the above example with Dr. Brown. Since offending the boss is the bigger risk, it is the boss who may have to define personal boundaries by carefully choosing some things to reveal that then legitimize Humble Inquiry to the rest of the team.

The fourth self—the unknown self—refers to those things that neither I nor the people with whom I have relationships know about me. I may have hidden talents that come out in a brand new situation, I may have all kinds of unconscious thoughts and feelings that surface from time to time, and I may have unpredictable responses based on psychological or physical factors that catch me by surprise. I have to be prepared for the occasional unanticipated feeling or behavior that pops out of me.

Now imagine the conversation as a social seesaw with two people getting to know each other, a reciprocal dance of self-exposure through alternately questioning and telling based on curiosity and interest. Gradual self-exposure will occur either through answers to Humble Inquiry or by deliberate revelations. If these early self-revelations are accepted by the other, then gradually more personal thoughts and feelings are put out as a test of whether the other will still react positively to them. In each move, we claim a little more value for ourselves and thereby make ourselves a little more vulnerable. If the other person continues to accept us, we achieve a higher level of trust in each other. What we think of as intimacy can then be thought of as revealing more and more of what we ordinarily conceal.

Humble Inquiry functions as an invitation to be more personal and is therefore the key to building a more intimate relationship. Early in a relationship, such invitations can be as basic as the senior surgeon asking the new nurse and technician their names or where they are from, thereby showing interest in them as whole people and not just in their professional roles.

In summary, conversations are inevitably complex because the messages are complex and nuanced even if the sender intends them to be very simple and direct. So even though Humble Inquiry can be defined as an attitude based on your curiosity, asking questions to which you do not know the answers, the implementation is complex because either you are not sure what you should be curious about or your question can be misunderstood. Being curious about and asking about something can easily become too personal and lead the other person to be offended. Therefore, the cultural rules about what is personal and what is intimate have to be understood and followed unless, by mutual agreement, they have somehow been suspended in a “cultural island,” a concept that will be explained in the last chapter.

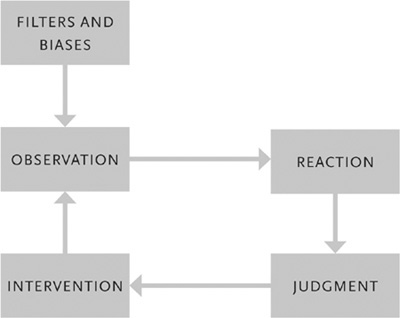

Psychological Biases in Perception and Judgment—ORJI

What comes out of our mouth and our overall demeanor in the conversation is deeply dependent on what is going on inside our head. We cannot be appropriately humble if we misread or misjudge the situation we are in and what is appropriate in that situation. We must become aware that our minds are capable of producing biases, perceptual distortions, and inappropriate impulses. To be effective in Humble Inquiry, we must make an effort to learn what these biases and distortions are.

To begin this learning, we need a simplifying model of processes that are, in fact, extremely complex because our nervous system simultaneously gathers data, processes data, proactively manages what data to gather, and decides how to react. What we see and hear and how we react to things are partly driven by our needs and expectations. Though these processes occur at the same time, it is useful to distinguish them and treat them as a cycle. That is, we observe (O), we react emotionally to what we have observed (R), we analyze, process, and make judgments based on our observations and feelings (J), and we behave overtly in order to make something happen—we intervene (I).12 Humble Inquiry is one category of such an intervention.

The ORJI cycle

OBSERVATION (O)

Observation should be the accurate registering through all of our senses of what is actually occurring in the environment and what the demands are of the situation in which we find ourselves. In fact, the nervous system is proactive, programmed through many prior experiences to filter data that come in. We see and hear more or less what we expect or anticipate based on prior experience, or, more importantly, on what we hope to achieve. Our wants and needs distort to an unknown degree what we perceive. We block out a great deal of information that is potentially available if it does not fit our needs, expectations, preconceptions, and prejudgments.

We do not passively register information. We select out from the available data what we are capable of registering and classifying, based on our language and culturally learned concepts as well as what we want and need. To put it more dramatically, we do not think and talk about what we see; we see what we are able to think and talk about.

Psychoanalytic and cognitive theories have shown us how extensive perceptual distortion can be. Perhaps the clearest examples of this are the defense mechanisms denial and projection. Denial is refusing to see certain categories of information as they apply to us, and projection is seeing in others what is actually operating in us. It has also been shown that our needs distort our perceptions, such as when our thirst makes us see anything in the desert as an oasis. To deal with reality, to strive for objectivity, to attempt to see how things really are—as artists attempt to do when they want to draw or paint realistically— we must understand and attempt to reduce the initial distortions that our perceptual system is capable of and likely to use.

REACTION (R)

The ORJI cycle diagram shows emotional reactions occur as a result of what we observe. There is growing evidence that the emotional response may actually occur prior to or simultaneously with the observation. People show fear physically before they perceive the threat. This being the case, the most difficult aspect of learning about our emotional reactions is that we often do not notice them at all. We deny feelings or take them so much for granted that we, in effect, short-circuit them and move straight into judgments and actions. We may be feeling anxious, angry, guilty, embarrassed, joyful, aggressive, or happy, yet we may not realize we are feeling this way until someone asks us how we are feeling or we take the time to reflect on what is going on inside us.

A common example occurs when we are driving and someone unexpectedly cuts in front of us. The momentary sensation of threat is a reaction that makes us observe that the person is cutting us off, which leads first to the instant judgment that (s)he has no right and then to the intervention that we speed up to prevent it or pull up even at the next light to shout at the person who cut us off. The instant judgment prevents us from the safer alternative of slowing down to allow the other car in.

Feelings are very much a part of every moment of living, but we learn early in life that there are many situations where feelings should be controlled, suppressed, overcome, and in various other ways deleted or denied. As we learn sex roles and occupational roles, and as we become socialized into a particular culture, we learn which feelings are acceptable and which ones are not, when it is appropriate to express feelings and when it is not, when feelings are “good” and when they are “bad.”

In our task-oriented pragmatic culture we also learn that feelings should not influence judgments, that feelings are a source of distortion, and we are told not to act impulsively on our feelings. But, paradoxically, we often end up acting most on our feelings when we are least aware of them, all the while deluding ourselves that we are carefully acting only on judgments. And we are often quite oblivious to the influences that our feelings have on our judgments.

It is not impulsiveness per se that causes difficulty—it is acting on impulses that are not consciously understood and hence not evaluated prior to the action that gets us into trouble. The major issue around feelings, then, is to find ways of getting in touch with them so that we can increase our areas of choice. It is essential for us to be able to know what we are feeling, both to avoid bias in responding and to use those feelings as a diagnostic indicator of what may be happening in the relationship.

Practicing Humble Inquiry before we judge and act becomes an important way of preventing unfortunate consequences. Recall the story of the student who shouted at his daughter for interrupting his studying instead of asking her why she had knocked on his study door. An important use of Humble Inquiry in this regard is to inquire of oneself before one acts. Ask yourself, “What am I feeling?” before you go to judgment and action. If the driver had asked that question before speeding up, he or she might have recognized the sense of threat and followed up with, “Why am I so foolish as to risk an accident when I don’t even know why this other driver is in such a hurry?”

JUDGMENT (J)

We are constantly processing data, analyzing information, evaluating, and making judgments. This ability to analyze prior to action is what makes humans capable of planning sophisticated behavior to achieve complex goals and sustain action chains that take us years into the future. The capacity to plan ahead and to organize our actions according to plan is a unique aspect of human intelligence.

Being able to reason logically is, of course, essential. But all of the analyses and judgments we engage in are worth only as much as the data on which they are based. If the data we operate on is misperceived or our feelings distort it, then our analysis and judgments will be flawed. It does little good to go through sophisticated planning and analysis exercises if we do not pay attention to the manner in which the information we use is acquired and what biases may exist in it. Nor does analysis help us if we unconsciously bias our reasoning toward our emotional reactions. It has been shown that even under the best of conditions we are only capable of limited rationality and make systematic cognitive errors, so we should at least try to minimize the distortions in the initial information input.

The most important implication is to recognize from the outset that our capacity to reason is limited and that it is only as good as the data on which it is based. Humble Inquiry is one reliable way of gathering data. For example, when I perceive someone in need of help lying on the sidewalk, before reaching down to help them up I should ask, “Do you need help, how can I help you?” Or, if my boss has told me after the meeting, “That presentation didn’t go well,” ask, “Can you tell me a little more, what aspect are you referring to?” before you leap into defensive explanations.

INTERVENTION (I)

Once we have made some kind of judgment, we act. The judgment may be no more than the decision to act on emotional impulse, but that is a judgment nevertheless, and it is dangerous to be unaware of it. In other words, when we act impulsively, when we exhibit what we think of as knee-jerk reactions, it seems as if we are short-circuiting the rational judgment process. In fact, what we are doing is not short-circuiting but giving too much credence to an initial observation and our emotional response to it. Knee-jerk reactions that get us into trouble are interventions that are judgments based on incorrect data, not necessarily bad judgments. If someone is attacking me and I react with instant counterattack, that may be a very valid and appropriate intervention. But if I have misperceived and the person was not attacking me at all, then my counterattack makes me look like the aggressor and may lead to a serious communication breakdown.

The main reason why Humble Inquiry becomes such an important skill is that genuine curiosity and interest minimizes the likelihood of misperception, bad judgment, and hence, inappropriate behavior. In the culture of Tell, the biggest problem is that we don’t really know how valid or appropriate what we tell is to the situation. If we want to build a relationship with someone and open up communication channels, we have to avoid operating on incorrect data as much as we can. Checking things out by asking in a humble manner then becomes a core activity in relationship building.

Reflective reconstruction of the ORJI cycle often reveals that one’s judgment is logical but is based on “facts” that may not be accurate; hence the outcome may not be logical at all. It follows, therefore, that the most dangerous part of the cycle is the first step, where we take it for granted that what we perceive is valid enough to act on. We make attributions and prejudgments rather than focusing as much as possible on what really happened and what the other person really meant. The time where Humble Inquiry is often most needed is when we observe something that makes us angry or anxious. It is at those times that we need to slow down, to ask others in a humble way in order to check out the facts, and to ask ourselves how valid our reaction is before we make a judgment and leap into action.

In Summary

When we consider the two communication models together, we can see that even ordinary conversation is a complex dance involving moment-to-moment decisions on what to say, how to say it, and how to respond to what the other says. What we choose to reveal is very much a product of our perception of the situation and our understanding of the cultural rules that apply in that situation. Our initial biases in what we perceive and feel, how we judge situations, and how we react all reflect our culture and our personal history. We are all different because we have different histories both culturally and personally. And, most importantly, our perceptions of our roles, ranks, and statuses within a given situation predispose us to assume that we know what is appropriate. Situations in which participants have different perceptions of their roles, ranks, and statuses are, therefore, the most vulnerable to miscommunication and unwitting offense or embarrassment. It is, in fact, a miracle that we communicate as well as we do.

Common language based on a common culture helps. Insight into the complexities as described in this chapter helps. And a bias toward asking before telling or leaping into action helps. The reason asking is a strength rather than a weakness is that it provides a better chance of figuring out what is actually going on before acting.

If the tasks that society faces are becoming more complex and interdependent, and if the problem solvers working on these tasks are increasingly of different ranks, statuses, and cultures, the ability to ask in a humble way will become ever more important. In the final chapter, I provide some guidelines to become more proficient in this complex task of Humble Inquiry.

• Think about a recent conversation. Ask yourself whether you were picking up different messages from what the person was saying (open self) and what you were sensing (blind self)?

• Now think about yourself: what signals might you be sending from your blind self?

• Reveal to your spouse, partner, or good friend what you think are signals that you send from your blind self. Ask for comments, elaboration, and clarification so that you can learn more about your own communications.

• Think back over recent events and try to recall an incident when you acted inappropriately. Reconstruct what went wrong—inaccurate observation, inappropriate emotional reaction, bad judgment, or unsuitable action. Ask yourself where in the cycle you could have taken corrective action.

• Now take a few minutes just to reflect quietly on what you have learned in general so far.