Chapter 5

Identifying Project Resource Risk

“If you want a track team to win the high jump,

you find one person who can jump seven feet,

not several people who can jump six feet.”

—FREDERICK TERMAN, STANFORD UNIVERSITY

DEAN AND PROFESSOR OF ENGINEERING

Fred Terman is probably best known as the “father of Silicon Valley.” He encouraged Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, the Varian brothers, and hundreds of others to start businesses near Stanford University. Starting in the 1930s, alarmed at the paucity of job opportunities in the area, he helped his students start companies, set up the Stanford Industrial Park, and generally was responsible for the establishment of the world’s largest high-tech center. He was good at identifying and nurturing technical talent, and he understood how critical it is in any undertaking.

A lack of technical skills or access to appropriate staff is a large source of project risk for complex, technical projects. Risk management on these projects requires careful assessment of needed skills and commitment of capable staff.

Sources of Resource Risk

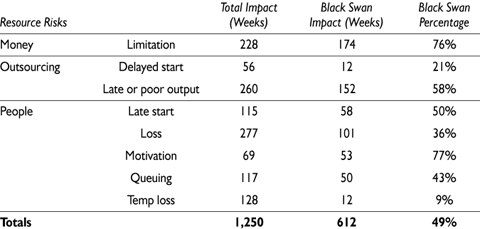

Like schedule risks, resource risks represent less than one-third of the records in the PERIL database. Resource risks have an average impact of nearly seven weeks, intermediate between scope and schedule risks. There are three categories of resource risk: people, outsourcing, and money. People risks arise within the project team. Outsourcing risks are caused by using people and services outside the project team for critical project work. The third category, money, is the rarest risk subcategory for the PERIL database, as few of the problems reported were primarily about funding. Money, however, has the highest average impact and the effect of insufficient project funding has substantial impact on projects in many other ways. The root causes of people and outsourcing risk are further characterized by type, shown in the following summary.

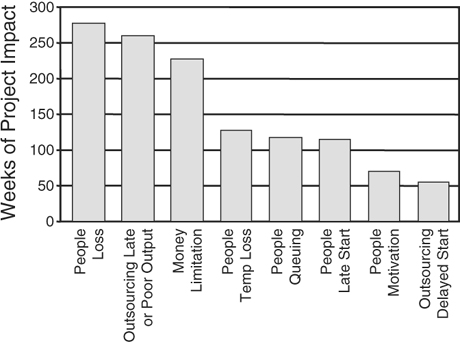

A Pareto chart of overall impact by type of risk is in Figure 5-1. Although risks related to internal staffing dominate the listed resource risk subcategories, both outsourcing and money risks are included in the top three.

People Risks

Risks related to people represent the most numerous resource risks, constituting almost 20 percent of the entire database and nearly two-thirds of the resource category. People risks are subdivided into five sub-categories:

Figure 5-1. Total project impact by resource root-cause subcategories.

1. Loss: Permanent staff member loss to the project due to resignation, promotion, reassignment, health, or other reasons

2. Temporary loss: Short-term staff loss due to illness, hot site, support priorities, or other reasons

3. Queuing: Slip due to other commitments for needed resources or expertise

4. Late start: Staff not available at project start; often because of late finish of previous projects

5. Motivation : Loss of team cohesion and interest; typical of long projects

Loss of staff permanently had by far the highest overall impact, resulting in an average slip of almost seven weeks. Permanent staff loss represented about one-third of the people risks. The reasons for permanent staff loss included resignations, promotions, reassignments to other work or different projects, and staffing cutbacks. Discovering these risks in advance is difficult, but good record-keeping and trend analysis are useful in setting realistic project expectations.

Temporary loss of project staff was the next most common people-related risk, with roughly another third of the total. Its overall impact was lower than for permanent staff loss, causing an average slip of nearly four weeks. The most frequently reported reason for short-term staff loss was a customer problem (a “hot site”) related to the deliverable from an earlier project. Other reasons for short-term staff loss included illness, travel problems, and organizational reorganizations.

Queuing problems were about 20 percent of the people-related risks in the PERIL database. The average schedule impact due to queuing was just in excess of four weeks. Most organizations optimize operations by investing the bare minimum in specialized (and expensive) expertise, and in costly facilities and equipment. This leads to a potential scarcity of these individuals or facilities, and contention between projects for access. Most technical projects rely on at least some special expertise that they share with other projects, such as system architects needed at the start, testing personnel needed at the end, and other specialists needed throughout the project. If an expert happens to be free when a project is ready for the work to start, there is no problem, but if he or she has five other projects queued up already when your project needs attention, you will come to a screeching halt while you wait in queue. Queuing analysis is well understood, and it is relevant to a wide variety of manufacturing, engineering, system design, computer networks, and many other business systems. Any system subject to queues requires some excess capacity if it needs to increase throughput. Optimizing organizational resources needed for projects based only on cost drives out necessary capacity and results in project delay.

Late starts for key staff unavailable at the beginning of a project also caused a good deal of project delay. Although the frequency was only a little more than 10 percent of the people-related resource risks, the average impact was nearly eight weeks. Staff joining the project late had a number of root causes, but the most common was a situation aptly described by one project leader as the “rolling sledgehammer.” Whenever a prior project is late, some, perhaps even all, of the staff for the new project is still busy working to get it done. As a consequence, the next project gets a slow and ragged start, with key people beginning their contributions to the new project only when they can break free of an earlier one. Even when these people become available, there may be additional delay, because the staff members coming from a late project are often exhausted from the stress and long hours typical of an overdue project. The “rolling sledgehammer” creates a cycle that self-perpetuates and is hard to break. Each late project causes the projects that follow also to be late.

Motivation issues were the smallest subcategory, at only a bit more than 5 percent of the people-related resource risks. However, these risks had an average impact of nearly nine weeks, among the highest for any of the subcategories in the PERIL database. Motivation issues are generally a consequence of lowering interest on long-duration projects, or due to interpersonal conflicts.

Thorough planning and credible scheduling of the work well in advance will reveal some of the most serious potential exposures regarding people. Histogram analysis of resource requirements may also provide insight into staffing exposures a project will face, but unless analysis of project resources is credibly integrated with comprehensive resource data for other projects and all the nonproject demands within the business, the results may not be useful. Aligning staffing capacity with project requirements requires ongoing attention. One significant root cause for understaffed projects is little or no use of project planning information to make or revise project selection decisions at the organization level, triggering the “too many projects” problem. Retrospective analysis of projects over time is also an effective way to detect and measure the consequences of inadequate staffing, especially when the problems are chronic.

Outsourcing Risks

Outsourcing risks account for more than a quarter of the resource risks. Though the frequency in the PERIL database is lower than for people risks, the impact of outsourcing risk was nearly seven weeks, about equal to the database average. Risks related to outsourcing are separated into two subcategories: late or poor outputs and delayed start.

Late or poor output from outsource partners is a problem that is well represented in the PERIL database. The growth of outsourcing in the recent past has been driven primarily by a desire to save money, and often it does. There is a trade-off, though, between this and predictability. Work done at a distance is out of sight, and problems that might easily be detected within a local team inside the organization may not surface as an issue until it is too late. Nearly three-quarters of the outsourcing risks involved receiving a late or unsatisfactory deliverable from an external supplier, and the average impact for these incidents was nearly eight weeks. These delays result from many of the same root causes as other people risks—turnover, queuing problems, staff availability, and other issues—but often a precise cause is not known. Receiving anything the project needs late is a risk, but these cases are compounded by the added element of surprise; the problem may be invisible until the day of the default (after weeks of reports saying, “Things are going just fine . . .”), when it is too late to do much about it. Lateness was often exacerbated in cases in the PERIL database because work that did not meet specifications caused further delay while it was being redone correctly.

Delayed starts are also fairly common with outsourced work, causing about one-quarter of the outsourcing problems. Before any external work can begin, contracts must be negotiated, approved, and signed. All these steps are time consuming. Beginning a new, complex relationship with people outside your organization can require more time than expected. For projects with particularly unusual needs, just finding an appropriate supplier may cause significant delays. The average impact from these delayed starts in the database was just over one month.

Outsourcing risks are detected through planning processes, and through careful analysis and thorough understanding of all the terms of the contract. Both the project team and the outsourcing partner must understand the terms and conditions of the contract, especially the scope of work and the business relationship.

Money Risks

The third category of resource risks was rare in the PERIL database, representing less than 10 percent of the resource risks and about 2 percent of the whole. It is significant, however, because when funding is a problem, it is often a big problem. The average impact was the highest for any subcategory, at over thirteen weeks. Insufficient funding can significantly stretch out the duration of a project, and it is a contributing root cause in many other subcategories (people turnover due to layoffs and outsourcing of work primarily for cost reasons, as examples).

“Black Swans”

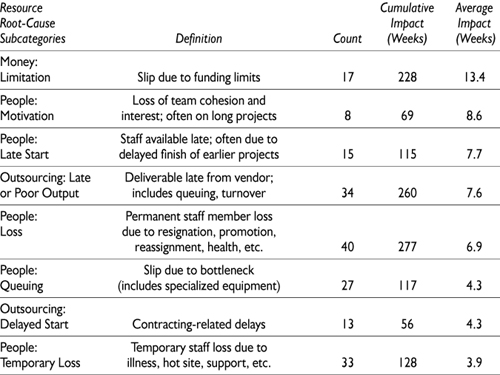

The worst 20 percent of the risks in the PERIL database are deemed black swans. These “large-impact, hard-to-predict, rare events” caused at least three months of schedule slip, and 33 of these most damaging 127 risks were resource risks. As with the black swans as a whole, the most severe of the resource risks account for about one-half of the total measured impact. The details are given in the following table.

As can be seen in the table, the black swan resource risks were distributed unevenly. The money category represents a much higher portion of the total, with outsourcing about as expected and people-related risks much lower.

Not surprisingly, money issues were a substantial portion of the black swan resource risks. Eight cases, more than half of the risks reported in this category, were in this group, including such problems as:

• Project budget was limited to the bare minimum estimated.

• Important parts of scope were missed because of insufficient resources.

• Not enough staff was funded to cover the workload.

• Major cutbacks delayed fixes that lost time and ultimately also cost a lot of money.

• Only half the resources required were assigned to the project.

There were also ten outsourcing black swan risks. Nine were due to late or poor output, with these among them:

• The vendor was unable to control the subproject and the work had to be redone.

• The supplier was purchased and reorganized; the project had to find a new supplier.

• Outsourced research work was not managed well, and all work was ultimately redone.

• Changes were agreed to, but the supplier shipped late and it failed.

• The subcontractor failed to understand technology and requirements.

• The partner on the project defaulted.

• The supplier was not able to meet deadlines.

There was also a black swan outsourcing risk due to a delayed start when settling the terms of the agreement and negotiating the contracts took months and caused the project to begin late.

There were fifteen additional black swan people risks. This category had a smaller proportion of severe risks but did have the largest total number of these severe risks.

The three black swan risks associated with motivation were over one-third of all the motivation risks, and they account for nearly 80 percent of the impact from this category of risk. These risks were:

• Management mandated the project but never got team buy-in.

• Staff got along poorly and frequently quarreled.

• The product manager disliked the project manager.

Permanent staff loss also caused a lot of pain and led the list of black swan people risks with five examples:

• A key staff member resigned.

• The committed medical expert was no longer available.

• Staffing suffered cutbacks.

• Specialists were lost, including designers, business analysts, and QA/testers.

• There was a companywide layoff.

There were also three black swan project risks due to queuing, where projects were slowed by lack of access to specific resources:

• Insufficient QA resources were available to cover the auditing tasks and training tasks.

• Key decisions were stalled when no system architect was available.

• Several projects shared only one subject matter expert.

There were three more major people risks caused by late staffing availability. All were due to people who were trapped on a delayed prior project. Temporary loss of people caused only one back swan risk, because of an unexpectedly early start of conflicting peak-season responsibilities that resulted in a protracted loss of project staff.

Additional examples of resource risks are listed in the Appendix.

Resource Planning

Resource planning is a useful tool for anticipating many of the people, outsourcing, and money risks. Inputs to the resource planning process include the project work breakdown structure (WBS), scope definition, activity descriptions, duration estimates, and the project schedule. Resource requirements planning can be done in a number of ways, using manual methods, histogram analysis, or computer tools.

Resource Requirements

Based on the preliminary schedule and assumptions about each project activity, you will need to determine the skills and staffing required for each activity. It is increasingly common, even for relatively small projects, to use a computer scheduling tool for this. For all project work, identify staff by name. Although preliminary resource planning can start using functions or roles, effort estimates done without staffing information are imprecise, and there is significant resource risk until the project staff is named and committed. Identify as a risk any work depending on staff members who are not named during project planning.

For the project as a whole, also identify all holidays, scheduled time off, significant nonproject meetings, and other time that will not be available to the project. Do this for each person as well, and identify any scheduling differences for different regions, countries, and companies involved in the project. A computer scheduling tool is a good place to store calendar information, such as holidays, vacations, and any other important dates. If you do use a computer tool, enter all the calendar data into the database before you begin resource analysis.

You also need to determine the amount of effort available from each contributor. Even for “full-time” contributors, it is difficult to get more than five to six hours of project activity work per day, and “part-time” staff will contribute much less.

Particularly for project activities that are already identified as potential risks, such as those on the critical path, determine the total effort required and verify who will do the necessary work. Knowing the resources your project will need and how this compares with what is available is central to identifying and managing project risk.

Whether you do this analysis manually by inspection of the project plans, through a tabular or spreadsheet approach, or by using resource analysis functionality in a computer spreadsheet, your goal will be to detect resource shortfalls that could hurt your project. Work to uncover any resource overcommitments and undercommitments. Even if you do use a computer tool, and there are many, remember that a scheduling tool is primarily a database with specialized output reports. The quality of the information the tool provides can never be any better than the quality of the data that you put in. You and the project team must still do the thinking; a computer cannot plan your project or identify its risks.

Histogram Analysis Using Computer Tools

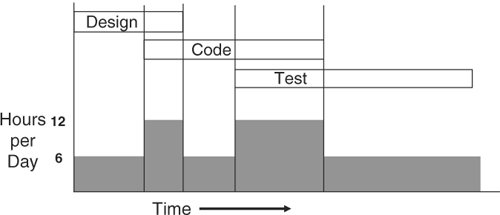

For more complicated projects, graphical resource analysis is useful. Resource histograms can be used to show graphically where project staffing is inadequate on an individual-by-individual or an overall project basis. The graphical format provides a visible way to identify places in the preliminary schedule where project staffing fails to support the planned workflow, as shown in Figure 5-2. In this case, the effort profile for a project team member expected to contribute to all these activities shows that this person must work a double shift where the activities overlap.

The benefits of entering resource data into a computer scheduling tool include:

• Identifying resource risks

• Improving the precision of the schedule

• Building compelling evidence for negotiating budgets and schedules

• Focusing more attention on project estimates

Figure 5-2. Histogram analysis for an individual.

These benefits require some investment on your part. Histogram analysis adds complexity to the planning process, and it increases the effort for both planning and tracking. In your resource analysis, allocate sufficient effort for this into your overall project workload.

Be particularly wary of assumptions that contribute to project risk, such as the dependability of committed start dates for project contributors. Both late starts and queuing delays were significant sources of risk in the PERIL database.

Resource shortfalls are not limited to staffing. Early in your project, assess your project infrastructure: the equipment, software, and any other project assets. If required computers, software applications, test gear, instruments, communications and networking equipment, or other available hardware elements are not adequate or up to date, plan to replace, upgrade, or augment them. The effort and money to do this tends to be easiest to obtain during the planning and start-up phases of a new project. Getting familiar with new hardware and software is less disruptive early than it will be in the middle of the project, when it could disrupt high-priority project activities.

Staff Acquisition

Histograms and other project analysis are necessary, but rarely sufficient to determine whether the project has the staffing and skills required to do the work. Particularly for the riskiest project activities, revalidate both the skills needed and your effort estimates.

Skill Requirements

Through project scope definition and preliminary planning, identify specific skills and other needs required by your project. Your initial project staffing will often include adequate coverage for some or even most of these, but on many projects there are substantial gaps. These gaps will remain project resource risks until they are resolved.

Specific skills that are not available on the project team might be acquired by negotiating for additional staff, or through training or mentoring. In some cases, needed skills can be added through outsourcing. These options are most possible when the need is made known early and supported with credible planning data. You may also be able to replan the parts of the project that require unavailable skills to use other methods that require only skills already available on the project team. If there are knowledge gaps that can be filled through training, plan to do it early in the project. Postponing training until just before you need it increases two risks: that the time or money required for it will no longer be available, and that the “ramp-up time” to competence may exceed what you planned. (Learning curve issues were a major source of schedule risk in the PERIL database.) Building new skills can also be a powerful motivator and team builder—both of which can reduce risk for any project.

The ultimate goal of staff acquisition is to ensure that all project activities are aligned with specific individuals who are competent and can be counted on to get the work done. Two significant resource risks related to staff acquisition are unnamed staff members and contributors with unique skills. Every identified staffing need on your project roster that remains blank, identified only with a function or marked “to be hired,” is a risk. Even if these people are later named, their productivity may not be consistent with your estimates and assumptions. It is also possible that the names will still be missing even after work is scheduled to begin—and some staffing requirements may never be filled. Plans completed with unassigned staffing are unreliable, and every project staffing requirement that lacks a credible commitment by an actual person is a project risk.

Unique skills also pose a problem. When project work can be assigned to one of several competent contributors, there is a good chance that it will be done adequately and on schedule. When only a single person knows how to do the work, the project faces risk. There are many reasons why a necessary person may not be available to the project when needed, including illness, resignation, injury, or reassignment to other higher priority work. There are no alternatives for the project when this happens; work on a key part of the project will halt. Whenever a key part of your project depends on access to a single specific individual, note it as a risk.

Revisiting Estimates

As noted in Chapter 4, resource planning and activity estimating are interrelated. As the staffing plan for the project comes together, additional resource risks become apparent through review of the assumptions you used for estimating. Project resource risks are usually most severe for activities that are most likely to impact the project schedule—activities that are on the critical path, or have little float, or have worst-case estimates that could put them on the critical path. Reviewing the effort estimates for these and other project activities reveals resource risks related to staff ability, staff availability, and the work environment.

Staff ability Individual productivity varies a great deal, so it matters who will be involved with each project activity. Even for very simple tasks, there can be very great differences in performance. Cooks often encounter the requirement for “one onion, chopped.” The amount of time this task will take depends greatly on the person undertaking it. For a home cook, it might take two or three minutes (assuming that the majority of the chopping is restricted to the onion). A trained professional chef, as watchers of television cooking know, dispatches this task in seconds. On the other extreme one finds the perfectionist, who could make an evening out of ensuring that each fragment of onion is identical in size and shape.

Productivity measurements for “knowledge” work of most kinds show a similar wide spectrum. Research on productivity shows that people who are among the best at what they do typically work two to three times as fast as the average, and they are more than ten times as productive as the slowest. In addition to being faster, the best performers also make fewer errors and do much less rework.

Differences due to variations in productivity are a frequent source of inaccurate project estimates. Project leaders often plan the project using data from their own experience, and then delegate the work to others who may not be as skilled or as fast as they are (or think they are). When there are historical metrics that draw on a large population, you can accurately predict how fast an average person will be able to accomplish similar work. If your project contributors are significantly more (or less) productive than the average, your effort and duration estimates will be accurate only if they are adjusted accordingly. When you do not know who will be involved in the work, risks can be significant.

Staff availability No one can ever actually work on project activities “full time.” Every project contributor has commitments even within the project that are above and beyond the scheduled project work, such as communications. Further, some team members will inevitably be responsible for significant work outside the project. Studying computer and medical electronics firms, Wheelwright and Clark (in Revolutionizing Product Development) reported the effect of assigning work on parallel projects to engineers. For engineers assigned to a single project or two projects, about 70 percent of the time spent went into project activities, roughly equivalent to the often-quoted “five or six” hours of project work per day. With three and more projects, useful time plummets precipitously. An engineer with five projects deals with so much overhead that only 30 percent of the time remains for project activities. Not all projects are equal, so when you are faced with this situation, find out how your overcommitted contributors prioritize their activities. Ask each part-time contributor about both the importance and the urgency of the work on your project. Both matter, but it’s a lack of urgency that will hurt your project the most. When contributors see your project’s work as low priority, it is a risk. If you are unable to adjust it, you may even need to consider alternative resources or other methods to do the project work.

The “too many projects” problem takes a heavy toll on project progress, and estimates of duration or effort that fail to account for the impact of competing priorities can be absurdly optimistic.

Project environment The project environment is yet another factor that has an impact on the quality of project estimates. Noise, interruptions, the workspace, and other factors may erode productivity significantly. When people can work undistracted, a lot gets done.

This is not typical, though. Frequent disturbances are commonplace, particularly with work done in an “open office” environment. The background noise level, nearby conversations, colleagues who drop by to chat, and other interruptions are actually much more disruptive than assumed in project estimates. People can’t shift from one activity to a different one instantaneously. Studies of knowledge workers indicate that it takes twenty minutes, typically, for the human brain to come back to full concentration following an interruption as short as a few seconds. A programmer who gets three telephone calls, a few IMs, or “quick questions” from a peer each hour cannot accomplish much.

Once the staffing for your project is set, consider all these factors, particularly the talent, proportion of time dedicated to your project, and the effect of the environment on the estimates in your project plan. Make adjustments as necessary, identify the resource risks, and add them to your project risk list.

Outsourcing

Outsourcing was a significant source of resource risk in the PERIL database, causing an average project slip of nearly seven weeks. Better management of outsourcing and procurement can uncover many of these problems in advance.

Not all project staffing needs can be met with internal people. More and more work on technical projects is done using outside services. It is increasingly difficult (and expensive) to maintain competence in all the fields of expertise that might be required, especially for skills needed only infrequently. A growing need for specialization underlies the trend toward increased dependence on project contributors outside the organization. Other reasons for this trend are attempts to lower costs and a desire in many organizations to reduce the amount of permanent staff. In the PMBOK® Guide, Project Procurement Management has four components:

2. Conduct procurements

3. Administer procurements

4. Close procurements

The first two of these provide significant opportunities for risk identification.

Planning Procurements

Outsourcing project work is most successful when the appropriate details and specifics are thoroughly incorporated into all the legal and other documentation used. Outsourced work must be specified in detail both in the initial request and in the contract, so that both parties have a clear definition for the work required and how it will be evaluated. Planning required to do this effectively is difficult, and it takes more effort and specificity than might ordinarily be applied to project planning.

Specific risks permeate all aspects of the procurement process, starting before any work directly related to outsourcing formally starts. The process generally begins with identification of any requirements that the project expects to have difficulty meeting with the existing staff. Procurement planning involves investigation of possible options, and requires a “make-or-buy” analysis to determine whether there are any reasons why using outside services may be undesirable or inappropriate. From the perspective of project risk, delegating work to dedicated staff whenever possible is almost always preferable. Communication, visibility, continuity, motivation, and project control are all easier and better for nonoutsourced work. Other reasons to avoid outsourcing may include higher costs, potential loss of confidential information, an ongoing significant need to maintain core skills (on future projects or for required support), and lack of confidence in the available service providers. Some outsourcing decisions are made because all the current staff is busy and there is no one available to do necessary project work. These decisions seem to be based on the erroneous assumption that project outsourcing can be done successfully with no effort. Ignoring the substantial effort required to find, evaluate, negotiate and contract with, routinely communicate with, monitor, and pay a supplier is a serious risk.

Although it may be desirable to avoid outsourcing, project realities may require it. Whenever the make-versus-buy decision comes out “buy,” there will be risks to manage.

Conducting Procurements

The next step in the outsourcing process is to develop a request for proposal (RFP), also known as request for bid, invitation to bid, and request for quotation. In organizations that outsource project work on a regular basis, there are usually standard forms and procedures to be used for this, so the steps in assembling, distributing, and later analyzing the RFP responses are generally not up to the project team. This is fortunate, because using well-established processes, preprinted forms, and professionals in your organization who do this work regularly are all essential to minimizing risk. If you lack templates and processes for this, consult colleagues who are experienced with outsourcing and borrow theirs, customizing as necessary. Outsourcing is one aspect of project management where figuring things out as you proceed will waste a lot of time and money and result in significant project risk.

Risk management also requires that at least one member of the project team be involved with planning and contracting for outside services, so that the interests of the project are represented throughout the procurement process.

Ensure that each RFP includes a clear, unambiguous definition of the scope of work involved, including the terms and conditions for evaluation and payment. Although it is always risky for any project work to remain poorly defined, outsourced work deserves particular attention. Inadequate definition of outsourced work leads to all the usual project problems, but it may result in even more schedule and resource risk. Problems with outsourced deliverables often surface late in the project with no advance warning (generally, following a long series of “we are doing just fine” status reports) and frequently will delay the project deadline, as is evident in the PERIL database, where delivery of a late or inadequate deliverable led to almost two months of average project slippage. There can also be significant increased cost due to required changes and late-project expedited work. Minimize outsourcing risks through scrupulous definition of all deliverables involved, including all measurements and performance criteria you will use for their evaluation.

As part of solicitation planning, establish the criteria that you will use to evaluate each response. Determine what is most important to your project and ensure that these aspects are clearly spelled out in the RFP, with guidance for the responders on how to supply the information that you require. Because the specific work on technical projects tends to evolve and change quickly, there is a good chance that well-established criteria for selecting suppliers will, sooner or later, be out of date. In light of your emerging planning data for the project, review the proposed criteria to validate that they are still appropriate. If the list of criteria used in the past seems in need of updating, do it before sending out the RFP. Establish priorities and relative weights for each evaluation criterion, as well as how you will assess the responses you receive. Communicating your priorities and expectations clearly in the RFP will help responders to self-qualify (or disqualify) themselves and will better provide the data you need to make a sound outsourcing decision.

Relevant experience is also important to avoiding outsourcing risk. In the RFP, request specifics from responders on similar prior efforts that were successful, and ask for contact information so you can follow up and verify. Even for work that is novel, ask for reference information from potential suppliers that will at least allow you to investigate past working relationships. Although it may be difficult to get useful reference information, it never hurts to request it.

Once you have established the specifics of the work to be outsourced, as well as the processes and documents you plan to use, the next step is to find potential suppliers and encourage them to respond. One of the biggest risks in this step is failure to contact enough suppliers. For some project work, networking and informal communications may be sufficient, but sending the RFP to lists of known suppliers, putting information on public Web sites, and even advertising may be useful in letting potential responders know of your needs. If too few responses are generated, the quality and cost of the choices available may not serve the project well.

Bringing the RFP process to closure is also a substantial source of risk. There are potential risks in decision making, negotiation, and the contracting process.

Decision-making risks include not doing adequate analysis to assess each potential supplier and making a selection based on something other than the needs of the project.

Inadequate analysis can be a significant source of risk. It is fairly common for the decisions on outsourcing to coincide with many other project activities, and writing and getting responses to an RFP often takes more time than expected. As a result, you may be left with little time to evaluate the proposals on their technical merit. Judging proposals by weight, appearance, or some other superficial criteria may save time, but is not likely to result in the best selection. Evaluating and comparing multiple complex proposals thoroughly takes time and effort. Before you make a decision, spend the time necessary to ensure a thorough evaluation. It’s like the old saying, “Act in haste; repent at leisure,” except in your case you will be repenting when you are very busy.

Another potential risk in the selection process is pressure from outside your project to make a choice for reasons unrelated to your project. Influences from other parts of the organization may come to bear during the decision process—to favor friends, to avoid some suppliers, to align with “strategic” partners of some other internal group, or to use a global (or a local) supplier. Because the decision will normally be signed and approved by someone higher in the organization, sometimes the project team may not even be aware of these factors until late in the process. Documenting the process and validating your criteria for supplier selection with your management can reduce this problem, but use of outside suppliers not selected by the project team represents significant, and sometimes disastrous, project risk.

Overall, you must diligently stay on top of the process to ensure that the selections made for each RFP are as consistent with your project requirements as possible.

Negotiation is the next step after selecting a supplier, to finalize the details of the work and finances. After a selection is made, the balance of power begins to shift from the purchaser to the supplier, raising additional risks. Once the work begins, the project will be dependent on the supplier for crucial, time-sensitive project deliverables. The supplier is primarily dependent on the project for money, which in the short run is neither crucial nor urgent. To a lesser extent, suppliers are also dependent on future recommendations from you (which can provide leverage for ongoing risk management), but from the supplier’s perspective, the relationship is mainly based on cash.

Effective and thorough negotiation is the last opportunity for the project to identify (and manage) risks without high potential costs. All relevant details of the work and deliverables need to be discussed and clearly understood, so the ultimate contract will unambiguously contain a scope of work that both parties see the same way. Details concerning tests, inspections, prototypes, and other interim deliverables must also be clarified. Specifics concerning partial and final payments, as well as the process and cost for any required changes or modifications, are also essential aspects of the negotiation process. Failure to conduct thorough, principled negotiation with a future supplier is a potential source of massive risk. Shortening a negotiation process to save time is never a good idea.

Because the primary consideration on the supplier side is financial, the best tactic for risk management in negotiation is to strongly align payments with achievement of specific results. Payment for time, effort, or other less tangible criteria may allow suppliers to bill the project even while failing to produce what your project requires. When negotiating the work and payment terms, the least risky option for you as the purchaser is to establish a “payment for result” contract.

Outsourcing risk can also be lowered by negotiating contract terms that align with specific project goals. Although a contract must include consequences for supplier nonperformance, such as nonpayment, legal action, or other remedies, these terms do little to ensure project success. If the supplier fails to perform, your project will still be in trouble. Lack of a key deliverable will lead to project failure, so it is also useful to negotiate terms that more directly support your project objectives. If there is value in getting work done early, incentive payments are worth considering. If there are specific additional costs associated with late delivery, establish penalties that reduce payments proportionate to the delay. For some projects, more complex financial arrangements than the simple “fee for result” may be appropriate, where percentages of favorable variances in time or cost are shared with the supplier and portions of unfavorable ones may be deducted from the fees. Negotiating terms that more directly support the project objectives and involve suppliers more deeply in the project can significantly reduce outsourcing risks.

If the negotiation process, despite your best efforts, results in terms that represent potential project problems, note these as risks. In extreme cases, you may want to reconsider your selection decision, or even the decision to outsource the project work at all.

Contracting follows agreement on the terms and conditions for the work. These terms must be documented in a contract, signed, and put into force. One effective way to minimize risk is to use a well-established, preprinted contract format to document the relationship. This should include all of the information that a complete, prudent contract must contain, so the chances of leaving out something critical, such as protection of confidential information or proprietary intellectual property, will be reduced. For this reason, you can reduce project risk by using a standard contract form with no significant modifications or deletions. In addition, using standard formats will reduce the time and effort needed for contract approval. In large companies, contracts varying from the standard may take an additional month (or even more) for review, approval, and processing. Adding data to a contract is also generally a poor idea, with one big exception. Every contract needs to include a clear, unambiguous definition of the scope of work that specifies measurable deliverables and payment terms. A good contract also provides an explicit description of the process to be used if any changes are necessary.

One other source of risk in contracting is also fairly common for technical projects. The statement of work must be clear not only in defining the results expected but also in specifying who will be responsible. It turns out that this is quite a challenge for engineers and other analytical people. Most engineering and other technical writing is filled with passive-voice sentences, such as, “It is important that the device be tested using an input voltage varying between 105 and 250 volts AC, down to a temperature of minus 40 degrees Celsius.” In a contract, there is no place for the passive voice. If the responsible party is not clearly specified, the sentence has no legal meaning. It fails to make clear who will do the testing and what, if any, consequences there may be should the testing fail. To minimize risks in contracts, write requirements in the active voice, spelling out all responsibilities in clear terms and by name.

Finally, when setting up a contract, minimize the resource risk by establishing a “not to exceed” limitation to avoid runaway costs. Set this limit somewhat higher than the expected cost, to provide some reserve for changes and unforeseen problems, but not a great deal higher. Many technical projects provide a reserve of about 10 percent to handle small adjustments. If problems or changes arise that require more than this, they will trigger review of the project, which is prudent risk management.

Outsourcing Risks

There are a variety of other risks that arise from outsourcing. One of the largest is cost, even if the work seems to be thoroughly defined. Unforeseen aspects of the work, which are never possible to eliminate completely, may trigger expensive change fees.

Continuity and turnover of contract staff is a risk. Although people who work for another company may be loyal to your project and stay with it through the end, the probabilities are lower than for the permanent staff on your project. Particularly with longer projects, turnover and retraining can represent major risks.

Outsourcing may increase the likelihood of turnover and demotivation of your permanent staff. If it becomes standard procedure to outsource all the new, “bleeding edge” project work, your permanent staff gets stuck doing the same old things, project after project, never learning anything new. It becomes harder to motivate and hold on to people who have no opportunity for development.

There may also be hidden effort for the project due to outsourcing, not visible in the plan. Someone must maintain the relationship, communicate regularly, deal with payments and other paperwork, and carry the other overhead of outsourcing. Although this may all run smoothly, if there are any problems it can become a major time sink. The time and effort this overhead requires is routinely overlooked or underestimated.

Finally, the nature of work at a distance requires significant additional effort. Getting useful status information is a lot of work. You will not get responses to initial requests every time, and verifying what is reported may be difficult. You can expect to provide much more information than you receive, and interpreting what you do get can be difficult. Even if the information is timely, it may not be completely accurate, and you may get little or no advance warning for project problems. Working to establish and maintain a solid working relationship with outsourcing partners can be a major undertaking, but it is prudent risk management.

Project-Level Estimates

Once you have validated the effort estimates for each activity in the project WBS, you can calculate the effort required in each project phase and total project effort. The “shape” of projects generally remains consistent over time, so the percentages of effort for each project phase derived from your planning process ought to be consistent with the measured results from earlier projects. Whatever the names and contents of the actual project phases, any significant deviation in the current plan compared with historical norms is good reason for skepticism. It’s also evidence of risk; any plan that shows a lower percentage of effort in a given project phase than is normal has probably failed to identify some of the necessary activities or underestimated them.

Published industry norms may be useful, but the best information to use for comparison is local. How projects run in different environments varies a great deal, even for projects using a common life cycle or methodology. Historical data from peers can be helpful, but data directly from projects that you have run is better. Disciplined collection of project metrics is essential for accurate estimation, better planning, and effective risk management. If you have personal data, use it. If you lack data from past projects, this is yet another good reason to start collecting it.

Not all project phases are as accurately planned as others, because some project work is more familiar and receives more attention. The middle phases of most project life cycles contain most of the work that defines “what we do.” Programmers program; hardware engineers build things; tech writers write; and in general, people do what it says on their business card. Whatever the “middle” phases are called (development, implementation, execution, and so forth), it is during this portion of the work where project contributors use the skills in which they have the most background and experience. These phases of project work are generally planned in detail, and activity estimates are often quite accurate. The phases that are earlier (such as investigation, planning, analysis, and proposal generation) and later (test, rollout, integration, and ramp-up) are generally less accurate. Using the life-cycle norm data, and assuming the “development” portion of the plan is fairly accurate, it is possible to detect whether project work may be missing or underestimated in the other phases. If this analysis shows inadequate effort allocated to the early (or late) phases based on historical profiles for effort, it is a good idea to find out why.

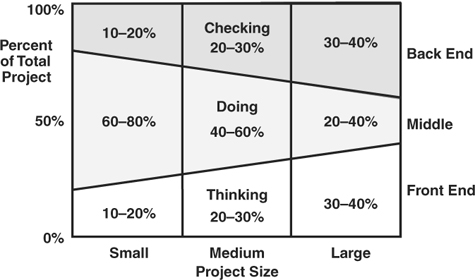

Figure 5-3. Effort by project phase.

Effort profiles for projects also vary with project size. By mapping the data from a large number of projects with various life cycles into a simple, generic life cycle, a significant trend emerges. The simplified project life cycle in Figure 5-3 is far less detailed than any you are likely to use, but all life cycles and methodologies define phases or stages that map into these three broad categories:

1. Thinking: All the initial work on a project, such as planning, analysis, investigation, initial design, proposal generation, specification, and preparation for the business decision to commit to the project.

2. Doing: The work that generally defines the project, including development. This is where the team rolls up their sleeves and digs into the creation of the project deliverable.

3. Checking: Testing the results created by the project, searching for defects in the deliverable(s), correcting problems and omissions, and project closure.

As projects increase in size and complexity, the amount of work grows rapidly. Project effort tends to expand geometrically as projects increase in time, staffing, specifications, or other parameters. In addition to this overall rise in effort, the effort spent in each phase of the project, as a percentage, shifts. As projects become larger, longer, and more complex, the percentage of total project effort increases for both early front-end project work and for back-end activities at the end of the project. A graphical summary of this, based on data from a wide rage of projects, is in Figure 5-3.

Small projects (fewer than six months, most work done with a small collocated team) spend nearly all their effort in “doing”—creating the deliverable. Medium projects (six to twelve months long, with more than one team of people contributing) might spend about half of their effort in other work. Projects that are still larger (one year or longer, with several distributed or global teams) will spend only about a third of the total effort developing project deliverables. This rise in effort both in the early and late stages of project work stems from the increased amount of information and coordination required, and the significantly larger number of possible failure modes (and, therefore, statistically expected) in these more difficult projects. Fixing defects in complex systems requires a lot of time and effort. Software consultant Fred Brooks (author of The Mythical Man-Month) states that a typical software project is one-third analysis, one-sixth coding, and one-half testing.

All this bears on project risk for at least two reasons. The first is chronic underestimation of late project effort. If a complex project is planned with the expectation that 10 percent of the effort will be in up-front work, followed by 80 percent in development, the final phase will rarely be the expected 10 percent. It will balloon to another 80 percent (or more). This is a primary cause of the all-too-common “late project work bulge.” Many entirely possible projects fail to meet their deadline (or fail altogether) due to underinvestment in early analysis and planning.

The second reason that life-cycle norms are valuable is found in the symmetry of Figure 5-3. The total effort required for a project tends to be lower when the initial and final phases of the work are roughly in balance. If the life-cycle norms for typical projects reveal that little effort is invested up front and a massive (generally unexpected) amount of effort is necessary at the end, then all projects are taking longer and costing more than necessary. Most projects that fail or are late because of end-of-project problems would benefit greatly from additional up-front work and planning.

Cost Estimating and Cost Budgeting

Inadequate funding was a major problem for nearly all the projects in the PERIL database with money risks, causing well over three months of average slippage. Project cost estimates are generally dominated by staffing and outsourcing costs, but also include expenses for equipment, services, travel, communications, and other project needs.

Staffing and Outsourcing Costs

Staffing costs can be calculated using the activity effort estimates, based on your histograms, spreadsheets, or other resource planning information. Using standard hourly rates for the project staff and your effort estimates, you can convert effort into project costs. For longer projects, you may also need to consider factors such as salary changes and the effect of inflation.

Estimate any outsourcing costs using the contracts negotiated for the services, working with figures about halfway between the minimum you can expect and the “not to exceed” amounts.

Equipment and Software Costs

The best time to request new equipment or upgrade older hardware, systems, and applications for a project is at the outset. You should assess the project’s needs, and research the options that are available. Inspect all equipment and software applications already in place to determine any opportunities for replacement or upgrade. Document the project’s needs and assemble a proposal including all potential purchases. As discussed earlier in the chapter, proposing the purchase and installation of new equipment at the start of the project has two benefits: getting approval from management when it is most likely, and allowing for installation when there is little other project work to conflict with it. Propose purchase of the best equipment available, so if purchase is approved you will be able to work as fast and efficiently as possible. If you propose the best options and only some of the budget is approved, you still may be able to find alternative hardware or systems that will enable you to complete your project. Estimate the overall project equipment expense by summing the cost of any approved proposals with other expected hardware and software costs.

Travel

The best time to get travel money for your project is at the beginning; midproject travel requests are often refused. As you plan the project work, determine when travel will be necessary and decide who will be involved. Travel planned and approved in advance is easier to arrange, less costly, and less disruptive for the project and the team members than last-minute, emergency trips. Request and justify face-to-face meetings with distant team members, getting team members from each site together at the project start, and for longer projects, at least every six months thereafter. Also budget for appropriate travel to interact with users, customers, and other stakeholders.

There are no guarantees that travel requested at the beginning of the project will be approved, or that it might not be cut back later, but if you do not estimate and request travel funds early, the chances get a lot worse.

Other Costs

Communication is essential on technical projects, and for distributed teams, it may be quite costly. Video- (and even audio-) conferencing technology may require up-front investments as well as usage fees. Schedule and budget for frequent status meetings, using the most appropriate technology you can find.

Projects that include team members outside of a single company may need to budget for setup and maintenance of a public-domain–secure Web site outside of corporate firewalls for project information that will be available to everyone. Other services such as shipping, couriers, and photocopying may also represent significant expenses for your project.

Cost Budgeting

Cost budgeting is the accumulation of all the cost estimates for the project. For most technical projects, the majority of the cost is for people, either permanent staff or workers under some kind of contract. The project cost baseline also includes estimated expenses for equipment, software and services, travel, communications, and other requirements. Whenever your preliminary project budget analysis exceeds the project cost objectives, the difference represents a significant project risk. Unless you are able to devise a credible lower-cost plan or negotiate a larger project budget, your project may prove to be impossible because of inadequate resources.

Documenting the Risks

Resource risks become visible throughout the planning and scheduling processes. Resource risks discussed in this chapter include:

• Activities with unknown staffing

• Understaffed activities

• Work that is outsourced

• Contract risks

• Activities requiring a unique resource

• Remote team members

• The impact of the work environment

• Budget requirements that exceed the project objectives

Add each specific risk discovered to the list of scope and schedule risks, with a clear description of the risk situation. This growing risk list provides the foundation for project risk analysis and management.

Panama Canal: Resources (1905–1907)

Project resource risk arises primarily from people factors, as demonstrated in the PERIL database, and this was certainly true on the Panama Canal project. Based on the experiences of the French during the first attempt, John Stevens realized project success required a healthy, productive, motivated workforce. For his project money was never an issue, but retaining people to do difficult and dangerous work in the hot, humid tropics certainly was. Stevens invested heavily, through Dr. Gorgas, in insect control and other public health measures. He also built an infrastructure at Panama that supported the productive, efficient progress he required. At the time of his departure from the project, Stevens had established a well-fed, well-equipped, well-housed, well-organized workforce with an excellent plan of attack.

This boosted productivity, but George Goethals realized that success also relied on continuity and motivation. He wanted loyalty, not to him, but to the project. The work was important, and Goethals used any opportunity he had to point this out. He worked hard to keep the workers engaged, and much of what he did remains good resource management practice today.

Goethals took a number of important steps to build morale. He started a weekly newspaper, the Canal Record. The paper gave an accurate, up-to-date picture of progress, unlike the Canal Bulletin periodically issued during the French project. In many ways, it served as the project’s status report, making note of significant accomplishments and naming those involved to build morale. The paper also provided feedback on productivity. Publishing these statistics led to healthy rivalries, as workers strived to better last week’s record for various types of work, so they could see their names in print.

It was crucial, Goethals believed, to recognize and reward service. Medals were struck at the Philadelphia Mint, using metal salvaged from the abandoned French equipment. Everyone who worked on the project for at least two years was publicly recognized and presented with a medal in a formal ceremony. People wore these proudly. In a documentary made many years after the project, Robert Dill, a former canal worker interviewed at age 104, was still wearing his medal, number 6726.

Goethals also sponsored weekly open-door sessions on Sundays when anyone could come with their questions. Some weeks over one hundred people would come to see him. If he could quickly answer a question or solve a problem, he did it then. If a request or suggestion was not something that would work, he explained why. If there were any open questions or issues, he committed to getting an answer, and he followed up. Goethals treated workers like humans, not brutes, and this engendered fierce loyalty.

Although all this contributed to ensuring a loyal, motivated, productive workforce, the most significant morale builder came early on, from the project sponsor. In 1906, Theodore Roosevelt sailed to Panama to visit his project. His trip was without precedent; never before had a sitting U.S. president left the country. The results of the trip were so noteworthy that one newspaper at the time conjectured that someday, a president “might undertake European journeys.”

Roosevelt chose to travel in the rainy season, and the conditions in Panama were dreadful. This hardly slowed him down at all; he was in the swamps, walking the railroad ties, charging up the slopes, even operating one of the huge, 97-ton Bucyrus steam shovels. He went everywhere the workers were. The reporters who came along were exhausted, but the workers were hugely excited and motivated.

On Roosevelt’s return to Washington, so much was written about the magnitude and importance of the project that interest and support for the canal spread quickly throughout the United States. People believed: “With Teddy Roosevelt, anything is possible.”