Chapter 5

Presenting the real you on stage

Like it or not, every time you present, you are being judged. Your audience will be critiquing not only your presentation style but also your ability as a leader. So if presenting is part of what you do, your presentation can affect, either negatively or positively, your future success and how people see you as a leader.

If you have senior leadership ambitions, it's imperative that you become an inspiring presenter. Organisations want inspiring leaders. Why? Because inspiring leaders engage and motivate a workforce, increase productivity, and attract and retain talented people.

Just look at Barack Obama. He won the US presidential election in 2008 because people believed he would be an inspiring leader, largely because he was an inspiring presenter.

Every time you present, you have an opportunity to increase your leadership presence. So it is worth investing time preparing for your presentation, and determining what will give you the biggest impact or the greatest return on your investment.

Due to the critical importance of presenting I have dedicated a fair number of pages in this book to it. Although the chapter title references the stage, keep in mind that you do not have to physically be on a stage for parts to be relevant. Your stage could be the boardroom or your stage could be around the table at your next team meeting. Your stage could be literal or lateral, and the information in this chapter is relevant regardless of whether you are speaking to thousands or to your team.

So where to begin? First, resist the urge to open up PowerPoint or Keynote and start tapping away. Whenever I have to do a presentation, I go to my favourite cafe and map out my presentation on a single piece of paper.

Over the years I've developed a winning formula for my presentations. I used to always start with the key messages I wanted to convey, but I have since realised there is an earlier place to start — purpose.

This chapter is aimed at providing you with techniques and a framework to help you prepare for your presentation and have the best possible shot of presenting the real you on stage.

EVERY TIME YOU PRESENT, YOU HAVE AN OPPORTUNITY TO INCREASE YOUR leadership PRESENCE. SO IT IS WORTH INVESTING TIME PREPARING FOR YOUR PRESENTATION, AND DETERMINING WHAT WILL GIVE YOU THE BIGGEST IMPACT OR THE GREATEST RETURN ON YOUR INVESTMENT.

Start with the why

In chapter 4, I cover Simon Sinek's ideas about understanding the importance of ‘why’ you do something. In his simple, yet powerful and inspirational TED talk, ‘Start With Why’, Simon Sinek starts by drawing a circle around the question ‘Why?’ He then states his main point, ‘People don't buy what you do; they buy why you do it’. The ‘why’ should be at the centre of everything you do. If you have not seen this TED talk, I recommend you watch it at some stage.1

The question of ‘why?’ is exactly where you have to start if you want to determine the purpose of your presentation.

Understand the purpose for your audience

Spending a few minutes on understanding why you are presenting is definitely worthwhile. Doing so will help you gain clarity and will form the foundation of how you build your presentation.

To identify the purpose of your presentation, ask yourself the following four questions:

What do I want my audience to think?

What do I want my audience to feel?

What do I want my audience to do?

What problem am I solving for my audience?

Obviously the purpose of your presentation will change every time you do a different presentation, even if it is similar content. So you'll need to ask yourself these questions for each and every presentation you do.

Ask yourself this: at the end of your presentation, what do you want your audience to do? What is it you want to achieve? Before you start thinking about your content and arranging it into PowerPoint slides, you have to think about ‘why’ you are presenting. What's the purpose of your presentation?

Understand the purpose for you

I worked with a client who was acting in the role of senior executive. She was going through the formal process of applying for the role she was acting in and her company was also interviewing several external candidates. While she was in the final stages of the interviewing process, she had to do a presentation to the board. I worked with her on her presentation, starting with the why. The purpose for the board was that they needed a high-level overview of the strategy and they wanted to feel confident that this was the right approach. My client also identified a purpose for her — and perhaps a hidden purpose for the board. Like it or not, coincidentally or not, this was a pseudo test and would informally became part of the decision process to identify if she was suitable to hold the senior executive role permanently.

Understanding this influenced the way we structured the presentation. She knew there was a chance that questions from certain board members could drag her into providing technical solutions, whereas she wanted to remain strategic. So we crafted appropriate responses if those situations occurred.

She knew she would be presenting to the board after hours of previous presentations, so she ditched the PowerPoint and went with an approach that would be refreshing and would introduce a change of pace.

She spent more time than usual identifying questions she thought the board would ask and worked on thorough and elegant responses for each of those.

While talking about purpose, one other aspect is worth a mention — the ‘listening cost’ of the room. If you are a CEO or a senior leader and you are presenting to 50 or 200 or more of your leaders, think about how much you are actually paying these people to sit and listen to you. Even if the number is lower, considering the ‘listening cost’ is important. On average, your leaders may earn about $100 an hour. If you have 100 such leaders in the room listening to you for an hour, that is a $10 000 ‘listening cost’. When you think about this, you would want to be good.

I hear many leaders comment on external speakers who are charging that amount, saying something along the line of, ‘They better be good for that money’ — and they have a point. If you're paying an external speaker $10 000 to do a 60-minute keynote, you expect them to be good. You could rightly expect them to be brilliant. But shouldn't we also place that same expectation on ourselves when we consider the ‘listening cost’ of the people sitting in the room? Not to mention what collectively the people listening could all achieve with those 100 hours. If we consider this aspect for meetings as well as presentations, we may start having shorter meetings and only invite the people who absolutely need to be there.

So now that I have added all that extra pressure, let's make your presentations rock and worth the ‘listening cost’.

Once you understand your purpose, you must spend some time looking at this purpose from your audience's perspective. You would be surprised how many presenters don't do this, or only do so at a surface level. But to be a more engaging presenter, you need to go beyond the surface level with an audience analysis and go to a deeper level.

First, the surface level. At this level you do need to understand a few things:

- Who are they?

- How many people are attending?

- What time of day will you be presenting? (After lunch or late afternoon?)

- Will you have to overcome any possible distractions? (For example, lunch being served.)

Then go beyond this and get to a deeper level. Following are some questions worth considering. You may not be able to answer them all and some may be irrelevant. If you don't know your audience at all, speak to someone who does know them and can give you insights into the questions.

Some questions worth thinking about include:

- What problems are you solving (if any)?

- What type of relationship (if any) do you have with your audience?

- What motivates them?

- What do they want from your presentation?

- What are three current challenges or concerns relevant to them?

- Do they want to be there?

- Do they really want to be there or are they expected to be there?

- How will they receive your messages?

- Is there a chance some will see your presentation in a negative light?

- What do you want them to think differently about after your presentation?

- What do you want them to ‘do’ differently, if anything?

- What do you want them to ‘feel’ differently?

When I run presentation workshops and take leaders through this exercise, without fail they gain an insight they had not thought of. So I encourage you to ask yourself these questions every time you present.

Your messages

Once you have clarity on your purpose and you have performed your audience analysis, you then need to think about your messages. Think of a target, with the content of your presentation representing the different rings in the target. The outer ring contains all the messages that your audience could know, the middle ring contains all the messages your audience should know, and in the centre are the messages your audience must know. Although you can easily fall into the trap of thinking all your messages are important, trying to communicate ten messages will most likely end with your audience remembering maybe only one or two (or none).

The pigs in George Orwell's Animal Farm eventually came up with the single commandment, ‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others’. But I'm not even going to pretend all messages are created equal. Some are just more important than others.

A good practice to get into is to write down all your messages and then prioritise them into the ‘must knows’, ‘should knows’ and ‘could knows’ (as shown in the following table). Then time will dictate how much you cover on each. But you also have other ways to get all the messages across. Perhaps the ‘should knows’ could be covered off in a question and answer session and the ‘could knows’ could be sent in a follow-up email after the presentation.

Distinguishing between ‘must knows’, ‘should knows’ and ‘could knows’

| Message | Must know | Should know | Could know |

| 1 | |||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | |||

| 4 | |||

| 5 | |||

| 6 | |||

| 7 | |||

| 8 | |||

| 9 | |||

| 10 |

‘Bumper sticker’ your message

Once you have written your messages down and prioritised them, think about how you can ‘bumper sticker’ your message. Here is a chance for you to move away from the corporate jargon, which has a tendency to bounce off people's heads, and trade that jargon for something that gets into their head, their heart or their gut. This is a chance to have a bit of fun, take a little risk and make your messages ‘sticky’.

Look at your messages and ask yourself, ‘If they were bumper stickers, what would they be?’

For example, Brian was a senior manager who was trying to communicate to his team that, no matter the communication material they were producing, most people were accessing this material on their smart phones. This meant his team needed to consider this during the design stage. He had written down his message as ‘Think of size when designing’. However, he bumper stickered his message to ‘size matters’. A little bit risqué perhaps, but a bit of fun and, most importantly, memorable.

When I work with sales teams on how to use storytelling in sales, my main message is, ‘When you are selling, reduce the focus on all the facts about the product and sell the value through storytelling, which will increase your sales’. When I bumper sticker that message, it translates to: ‘Facts tell; stories sell’.

By bumper stickering your message, you are creating two versions of how you can communicate the message — the business version and the bumper sticker version. The idea is to use both, or to keep both in mind and use each one depending on your audience. However, don't assume that just because you are talking to the board of directors or a senior leadership team they will not appreciate the bumper sticker message. People will most likely remember the bumper sticker and know what it stands for through your business version of the explanation.

Choose your delivery style

One way to help you be more real on stage is to use a variety of pedagogies, or modes of delivery. This not only makes it more interesting for your audience but also allows you to find a pedagogy or two that you feel most comfortable with. Using a pedagogy that you are more comfortable with, and more natural with, will allow you to be more relaxed when presenting and to present the real you on stage.

The next section explores a variety of pedagogies you could start to use.

Stories

So if you have just read the previous chapter, you're probably unsurprised that using stories is at the top of my list of the pedagogies you should use when presenting. In these situations, I believe you should always try to use personal stories to emphasise your messages. I also highly recommend starting your presentation with a story that shows your credibility and passion for what you are about to talk about. Walk on stage and simply start with your story.

For some reason, starting this way seems to freak people out a bit and they are really reluctant to do it. Perhaps because it is so unusual. I often see leaders start a conference by telling people where the toilets are and what to do in case of an emergency. Yes, this information is important and perhaps providing some of it is a legal requirement. But what is more important for you at that moment? Building credibility and instant connection with your audience or making sure they know where the toilets are? You're likely dealing with intelligent adults here and I reckon they may have already figured out where the toilets are. And if they haven't they can probably ask 100 other people before they need to be relying on the person on the stage.

START YOUR PRESENTATION WITH A STORY THAT SHOWS YOUR credibility AND passion FOR WHAT YOU ARE ABOUT TO TALK ABOUT. WALK ON STAGE AND SIMPLY START WITH YOUR STORY.

So all the ‘housekeeping’ type information may be important, but it does not have to be the first thing you say. Maybe tell your story first to get connection and engagement and then cover off on the housekeeping.

As discussed in chapter 4, remember that stories don't have to be overly personal, because you may not be comfortable sharing these on stage. But only you can decide what you're comfortable with. If you've reconciled yourself with the events you want to share and feel the story will help your audience engage with your main message, go ahead.

Props

Using props in presentations can be a creative and memorable way to demonstrate a point. For example, Sasha was a project leader who had to present to his senior leadership team the outcomes and recommendations of a project that he and his team had been working on. He was hoping to get funding and resources to implement a new internal employee contacts database and he wanted to emphasise how outdated the current system was.

During the presentation, Sasha held up the White Pages telephone directory (which, as you may know, is the size of about two bricks) and asked his audience if they could remember the last time they used one to find the contact details for someone. The answer (as he knew it would be) was years and years ago. He then pulled out his smart phone and said, ‘Of course, we all now use one of these’. He went on by saying, ‘In our personal life we use a device like this, yet at work we ask our employees to use a device like this’. With that, he dropped the very heavy White Pages directory on the table. It landed with a loud thud.

You can see from Sasha's example that the props don't have to be anything grand or outrageous. They just need to provide an opportunity to get your audience's attention, to have an impact and be memorable.

Using a personal prop can also be memorable and provide a great opportunity to bring the whole of you to your presentation — maybe a ‘most improved’ trophy from your under-11 tennis playing days or a framed photo of your grandparents. You just need to make sure they provide a good link to your main message.

Props can work especially well when combined with a story. Personal props and personal stories are very powerful.

Something unusual

Simply doing something unusual is another underused way to deliver memorable presentations.

About ten years ago I attended a full-day conference with a client. The conference was run by a global logistics company and they had brought about twenty people from around the Australasian region together in the beautiful setting of Indonesia. During the day, each country head would present what they had achieved for the year and cover their targets for next year.

Franc was the leader of the whole team and he was the final speaker. He had to present the overall business results for the last year and the targets for the following year. He had told me before the conference that the targets for the next financial year were a big stretch and he was expecting scepticism from his team, and perhaps even some serious backlash. Being a global company, these targets had been imposed on him and his initial reaction was also of scepticism. He, however, had known about the targets for a couple of weeks so had had time to work though his initial scepticism and was now feeling that the targets were achievable. He was hoping he could fast-track this process for his team so they could spend less time focusing on how the targets could not be achieved — and more time focusing on how they could be achieved.

Franc was co-presenting with one of his team members and what he did I still remember to this day. In fact, it is the only thing I remember from that entire day.

Franc and his co-presenter first went through what had been achieved for the previous twelve months, and then Franc put up the slide showing the following year's targets. Franc let people absorb these targets for about ten seconds and then he just said, ‘Those targets are ridiculous. There is no way we can achieve those.’ He then walked out the room, closing the door behind him. Everyone in the room just looked at each other wondering what was going on. Franc had a reputation for being a bit of joker but no-one was really sure if he was being serious or not. After about thirty seconds he re-entered the room, talking to himself in a voice that was still audible to the audience. He said, ‘Maybe the targets aren't so ridiculous after all. Maybe we could actually achieve them. It will be tough and we will have to do things a bit differently but what if we could achieve them? I think maybe I should give this a go.’

Now, at this stage it was obvious to everyone that this was part of the presentation, but it had the desired effect of fast-tracking the mindset of his team from ‘We can't do this’ to ‘We may able to achieve it’. Total acceptance wasn't that fast and there was certainly discussion about how much of a stretch the stretch targets were, but overall the approach worked. Franc took a risk, did something unusual and memorable, and it worked. More importantly, Franc was a bit of a fun guy. He liked to push the boundaries and not take things too seriously so this was absolutely true to him. The whole time it was the real Franc on stage.

I worked with another senior executive leader who was tasked with introducing the session after lunch. I had worked with him on a personal story he was going to share with his team, and on what he thought was important for leadership to him, to his business and the leaders he led. The setting was a large conference room of approximately 250 people, all sitting at tables of ten.

IF YOU ARE PREPARED TO TAKE A CALCULATED RISK AND DO SOMETHING JUST A LITTLE BIT unexpected, YOU CAN HAVE A HUGE IMPACT.

Instead of immediately taking to the stage, he decided to start at the very back of the room. He was wearing a lapel microphone so he was audible but, at the start, no-one knew where he was standing. Everyone was looking around to see where he was, and it only took a few seconds for them to find him at the back of the room. He spoke for about five minutes and slowly made his way to the stage in a bit of a crisscross fashion, walking past most tables as he did so. Doing something just a little bit different combined with a personal story had a big impact.

If you are prepared to take a calculated risk and do something just a little bit unexpected, you can have a huge impact. Take some advice from the ‘King’, Elvis Presley. He simply said, ‘Do something worth remembering!’

PowerPointlessness

In the early 1990s, PowerPoint was heralded as a saviour for those presenting information. PowerPoint held the promise of making every presentation engaging and exciting. Gone were the overhead transparencies (and gone was my beloved pointer in the shape of a hand). Once we mastered the sound effects and the transition mode, our presentations with PowerPoint were going to be amazing. Sure, most people couldn't read what was on the slide but it made a really cool ‘swoosh’ sound, which just added to the excitement. And with hundreds of clip art images to insert, every slide looked amazing.

With this amazing technology, we could present without actually having to think about our messages and our audiences. Except, of course, we couldn't. The reality was quite different. PowerPoint sentenced us to presentation hell. As audience members, we were trapped in this slow, horrible death by PowerPoint and, as presenters, we were trapped in the unavoidable expectation of using it … and, sadly, in most companies we still are. I mentor many leaders on how they can be more engaging presenters and I often suggest not using PowerPoint — only to hear responses along the lines of ‘I have to; it's expected and if I don't I will look unprepared’. So they reluctantly conform and give in to this weight of expectation. As Jean Paul Gaultier said, ‘To conform is to give in’.

Peter Norvig, director of research at Google, states that ‘PowerPoint doesn't kill meetings. People kill meetings. But using PowerPoint is like having a loaded AK-47 on the table: You can do very bad things with it.’ PowerPoint is not the problem; the poor use of it is the problem. Having said that, the way PowerPoint is designed lends itself to a very linear structure. Professor Edward Tufte's essay ‘The cognitive style of PowerPoint’ explains two major problems with PowerPoint that influence how ineffective it is as a communication platform.

Tufte explains that PowerPoint is most often used as a guide for the presenter, rather than as an aid for the audience, and it causes ideas to be arranged in an unnecessarily deep hierarchy, which then means the audience needs to be taken through a very linear progression.

A friend once asked me for help with his PowerPoint slides. He knew I did a fair bit of presenting so assumed I would be a technical whiz at PowerPoint. However, although I told him I could help him out a bit because I had worked in the corporate world where PowerPoint was the expected medium, I also advised him I now very rarely used it. He was a bit shocked and said, ‘But if you don't use PowerPoint, everyone is looking at you and not the slides’.

When I present, I actually want people to be looking at me and not being distracted by slides. What my friend highlighted was the fact that many presenters use PowerPoint as a crutch, to either deflect the attention off them or provide a guide for them so they don't forget their place.

That is why we see, to this day, slides with way too much text on them. Professor Tufte's research uncovered how PowerPoint was ineffectively used to brief senior NASA officials prior to the 2003 Columbia disaster, in which seven astronauts lost their lives after the space shuttle disintegrated during re-entry. The paper explores how vital information was buried in the PowerPoint presentation by the sheer amount of data on each slide.

Having heavily text-laden slides that your audience needs to read while you also talk them through the information is completely ineffective in taking in information.

Professor John Sweller from the University of New South Wales is well known for his work on cognitive load theory. Professor Sweller showed that the human brain processes information better if it is either in the written format or verbal. To get both versions of the same information simultaneously reduces the brain's ability to process the information. So asking a person to read off the slide as you are also talking reduces the effectiveness of your presentation. If you want people to read text, let them read it. Give them time to read it in silence and then perhaps ask some questions about it — such as, ‘What stood out for you in that text? What do you think will have the biggest impact for us? What are you most concerned about when reading that?’ According to Sweller, talking while also showing a diagram is fine, because the information is in a different form. But talking about the same words that are presented in the slide just puts too much load on the brain. Sweller sums up his theory by saying, ‘The use of the PowerPoint presentation has been a disaster’.

This research really challenges the way most of us have been instructed to develop our PowerPoint presentations. The current paradigm of capturing what you want to say in bullet points is just not working, and research is available to prove it. Of course, I don't really need to even cite the research — no doubt you've been in presentations where the presenters have talked through every bullet point on the slide. You know how boring and frustrating that is.

What we end up with is something called PowerPointlessness (a phrase coined by Barb Jenkins, who works at the South Australian Department of Education and Training). This covers ‘the senseless use of PowerPoint to communicate with too many bells and whistles, animated transitions between slides and very little substance’.

Of course, creating the bells and whistles in a PowerPoint slide is the easy bit. Ensuring your content is relevant and communicable in an engaging and inspiring way is the hard bit. You need to focus less on the sizzle and more on the sausage. And remember the words of Edward Tufte, who said, ‘If your words or images are not on point, making them dance in colour won't make them relevant’.

ENSURING YOUR CONTENT IS RELEVANT AND COMMUNICABLE IN AN ENGAGING AND INSPIRING WAY IS THE HARD BIT. YOU NEED TO FOCUS LESS ON THE sizzle AND MORE ON THE SAUSAGE.

The following sections discuss my top rules for creating presentations using PowerPoint (or Keynote).

Rule 1: Reduce your slides

Reduce both the content on your slides and the number of slides. People still put way too much content on their slides. I know of one organisation that had a minimum font size to try to address this, only to find their employees widened the margins of each slide.

My general rule for the ratio of PowerPoint slides to time is one slide for every three to five minutes. Always remember that less is more. If you're in doubt, try halving the number of slides you use. If you have 40 slides, make it 20; if you have 20, make it 10. Your audience does not need to see everything you are saying.

Rule 2: Make sure your slides are legible

Nothing is worse than showing a slide and saying, ‘You probably can't read this, but … ’ I'm sure you've seen such a slide. The font used is tiny or the diagram has so many labels attached it makes no sense. Showing such a slide is insulting to your audience, and it makes you look lazy and like a poor presenter. Promise me if during a presentation you ever utter the words, ‘You probably can't read this’ you will add ‘because I am a lazy presenter and I couldn't figure out a better way to communicate this to you’. Instead of having to make such an admission, think about using a handout instead, writing up key information on a whiteboard or replacing the information on the slide with your key point.

Rule 3: Remember a picture paints a thousand words

Every slide does not need to contain text. You can insert pictures, photos or simple diagrams. If you're using a story to convey a message, you could use an image that represents what you're saying. Just remember to keep it real — use your own photos rather than stock photos.

Once I was involved in a project that took nearly three years to complete. When I presented to the business about the completed project, I began by showing a photo of my daughter, who was two years old at the time. I knew full well that everyone was wondering why I was talking about my daughter and showing a picture of her. But one of the main points I wanted to get across from the start was how long and intensive the project had been. So I talked about my two-year-old daughter for about thirty seconds and then said, ‘When we started this project, I was six weeks pregnant.’

Rule 4: Split your presentation

Not everyone will turn up on the day of your presentation, and so some people may miss out on information. To combat this, many presenters produce a PowerPoint pack, rich in text, that can be emailed out to those who didn't attend. Providing the information by email is a good idea but, if you decide to do this, don't think you need to include the text within the slide. Instead, convert the information to a document in Word and add text there, or put all the additional text into the notes pages of the PowerPoint presentation.

Remember that presentations are about what's right for the audience first, and then about you. The PowerPoint slides should only be used if they assist the audience in understanding and remembering your message — they shouldn't be used as prompts for you.

Prompts are always a good idea but have separate notes for that. Again, adding additional text may help you but it will have a detrimental effect on people understanding and remembering your message.

Before the presentation

Success depends upon previous preparation, and without such preparation there is sure to be failure.

— Confucius, Chinese philosopher

You should do certain things before your presentation. Some of these should be done well in advance, like days or weeks before your presentation, some the night before or morning of your presentation, and others literally just before you take the stage. The following sections take you through these preparations.

Well before your presentation

To make sure you're organised and calm on the day of your presentation, you can do some prep work days or weeks beforehand. Consider working through the following.

Check requirements

Nothing is more off-putting than when you walk into a room expecting one thing and finding another. To avoid any surprises, going through requirements well in advance of your presentation is definitely worthwhile.

For example, if you need any form of technology, make sure it is present. If you have a slide deck of any description, send it to the organiser in advance and also have a copy on a memory stick — both in the original version (such as Keynote or PowerPoint) and also exported as a PDF. You may be using Keynote only to find that the venue does not support Mac products. Saving your presentation as a PDF averts this crisis.

Besides checking your requirements can be met, it is also a good idea to check details such as the following:

- What time will you be presenting?

- How many people will be there?

- What will the previous speaker be talking about?

- Will drinks or food be served while you are speaking?

On most occasions, if you get an answer to one of the preceding questions that's not ideal, you won't be able to do anything to change it — but you will at least minimise surprises on the day.

It is also a good idea to check the dress code. You need to dress to impress, but also dress for the situation. Sometimes that will require you suiting up, other times going more casual. My general rule is always go one standard higher than the dress code.

You can also use this as an opportunity to create and display a signature personal style that is relevant to who you are. I try to wear a splash of orange whenever I present because it is my branding colour, but you could go with anything that works for you. Creating your own signature style is a good way to be remembered.

CREATING YOUR OWN SIGNATURE STYLE IS A GOOD WAY TO BE remembered.

Request a lapel

I have never been a fan of the lectern, mainly because it places an unnecessary barrier between you and your audience and I think it is a contributing factor to stopping you from presenting the real you on stage.2

I was not surprised, then, to find that the word ‘lectern’ ultimately comes from the Latin word ‘legere’, which means ‘to read’. General definitions refer to the lectern as ‘a reading desk with a slanted top used to hold a sacred text from which passages are read in a religious service; a stand that serves as a support for the notes or books of a speaker’.

In fact, its first recorded use was in religious ceremonies where it was used as a place for the speaker to stand while presenting religious teaching during a church service. The sloping top of the lectern provided a convenient place for the speaker's scrolls, script or book, typically the Bible.

So no doubt many people associate lecterns with their more formal origins. If possible, break away from this formality and always get out from behind the lectern. Using a podium or lectern cuts off 50-plus per cent of most people's bodies, which is why the lectern is a physical barrier between you and your audience, preventing you from truly connecting. If you're on the short side, your audience may only see a head, part of your upper torso and your arms poking out the side.

When behind a lectern, you can also inadvertently do things that have a negative impact. You may find yourself leaning on it or gripping the sides, especially when nervous. Many speakers refer to their notes too often because they are literally right under their nose, not because they need to. This often means the presenter starts reading, which can have the complete opposite effect of presenting the real you on stage and should be avoided at all times.

So I highly recommend staying away from using a lectern if at all possible. If you must speak from one, don't hide behind it and don't grip it; make lots of eye contact and use large gestures that your audience can see.

The other option, of course, is to use a lapel microphone. You can attach this to your clothing so your hands are free and you are free to move out from behind the lectern. A handheld microphone also allows you this freedom but, if you have a choice, go with the lapel microphone over the handheld microphone. The main problem with the handheld microphone is that you have to hold it all the way through your presentation, which means you only have one arm to make hand gestures and you may also cause variance in sound quality as you move the microphone too close or too far away from your mouth.

Don't assume that a lapel microphone will be available on the day. Always enquire well in advance of your presentation.

A lapel mic consists of the battery component and the microphone, and both need to be secured to separate pieces of appropriate clothing. So what you wear needs careful consideration, especially if you are a female as the options beyond suit and shirt increase.

The battery compartment of the lapel mic can be a bit heavy, so it needs to be clipped to something that can support this weight, such as a sturdy leather belt.

Check what your bio says about you

As a professional speaker, I am often asked to provide a short bio so the MC of the event can introduce me, and perhaps so the organisers of the event can circulate this bio beforehand. Even if the conference organisers don't ask for this bio I provide it anyway, because I don't want my introduction to be left to chance. Losing control of what people say about you when they introduce you isn't a great start. Too often I have seen people introduced by the MC reading out a short version of their CV, listing previous jobs and experience. This can result in the audience being bored with that person before they even take the stage.

Your presentation bio is an opportunity for you to communicate real information about you that people would not ordinarily hear. It's a chance to build credibility, particularly on the topic you are about to talk about. It's an opportunity to demonstrate a value you have and it is a chance to be more real. And you don't even have to do anything too radical to stand out.

Your bio should be a combination of professional and personal achievements. It should include your past and your present and it should articulate your passion. Finally, it should be short and tailored for what is relevant to your audience.

My approach is to ‘Five P’ your bio, which means you should include information that covers professional, personal, past and present areas of your life. At the centre of everything should be your passion.

Following are some suggestions and examples you could include for each of your 5Ps. You don't need to include all of these in your bio because it would become too long. Just pick the ones that are the most relevant and remember this is all about being less boring and more real.

Past professional aspects could include:

- work history

- industry experience

- qualifications

- clients you have worked with

- locations you have worked in

- books you have authored.

Your present professional information could cover:

- current title

- current projects or work

- current clients

- future exciting opportunities.

Past personal aspects could be:

- past sporting achievements — for example, running a marathon

- past experiences you are proud of (even if these are a bit quirky) — runner-up in your Grade 2 spelling bee competition

- relevant family history — one leader I knew introduced himself by saying he was calm because he grew up in a house with seven sisters, three brothers and one bathroom.

Present personal areas could include:

- current hobbies or sport — for example, currently training for a half marathon

- future exciting opportunities such as holidays or significant family occasions — your son's wedding, the birth of your child or grandchild, your daughter's 21st birthday.

Your passion can be stated explicitly in your bio or implied. Your passion ideally should be related to helping your audience. For example, ‘I am passionate about helping leaders be the most inspiring leaders they can be’ or ‘I am obsessed about providing the best service to our customers’.

Prioritise practice

Being a real presenter does not mean you don't practise.

It's easy to say practise, practise, practise but the reality is that most of us just don't and that is due to a whole lot of reasons. Within my work with leaders (especially in the corporate world) I come across a variety reasons that stop them from practising, but by the far the most common is ‘time’.

Time is obviously a key factor that will determine how much we practise but the other factor is, or at least should be, familiarity of content. These will determine how much and what we practise before any presentation.

Time

Time is the biggest excuse I hear for not practising but it's not necessarily the real reason. Granted, as a leader you are often asked to give a presentation with very little notice but most of the time you at least get some notice. That may only be a few days or a few hours but there is normally enough notice to do some practice.

Content

How well you know the content will also determine how much time you need to practise. If you have presented the same content on numerous times, you probably need to do very little practice — although you should always check that the content and the way it is delivered is still appropriate for this exact audience. This may be as simple as running through what examples or stories you share to get your point across, and choosing the most appropriate ones for the audience you are about to present to.

Practice quadrant model

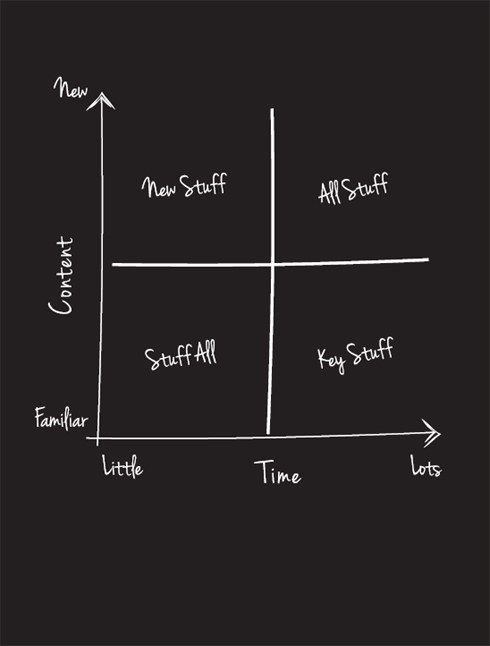

To determine how much practice time may be required, I came up with the practice quadrant model. This title is pretty dry, so after many variations I decided to call it the practical practise practice. A bit of a mouthful, yes, but the idea is that you should get into the practice of practising practically. The model is shown in the following illustration.

As you can see from the model, if the content is new and you have a lot of time, you should be aiming to practise ALL STUFF. What I mean by this is practise a lot and make sure you do a complete run-through of your presentation.

If you don't have a lot of time but the content is mostly new, just practise the NEW STUFF. So focus on the content that you are not overly familiar with and make sure you get your head around this new content. What is riding on the presentation can also affect what you choose to focus on.

If the content is familiar and you have time on your side, just practise the KEY STUFF — that is, the opening and closing, and the part that delivers your key message. If using a story, include practising the story in your key stuff. When practising only on key stuff and new stuff, you don't need to do a full run-through.

If, on the other hand, the content is familiar and you have little time, practise STUFF ALL. This is perhaps the only time I would say it is absolutely okay not to practise and still be able to do a good job. Any practice you do here is a bonus.

Some tips for practice

The power of practice can't be underestimated, and you should try to practise aloud, not just in your head. Practising aloud is a real test for ‘Is this the real you?’ You will hear what words are not sounding right for you. Try to use language you would normally use because this is about real talk and presenting the real you on stage.

Here are some further tips:

- Practise alone in the car, in the shower, or when you are going for a run or a walk.

- Practise by recording yourself on your phone and listening back to it.3

- Make sure you practise in front of someone, even if this is your partner at home. Presenting to just one other person makes your presentation come alive — there is now a dynamic, and you might speed up or slow down.

- Practise, practise and then practise some more.

The final tip, and perhaps the most important, is find a method that works for you. Some people suggest practising in front of a mirror. Personally I hate this because I look at myself and start to become all self-conscious about minor things. I end up focusing on me as opposed to my message or potential audience.

Find a way that works for you and go for it.

Just before your presentation

Even with the best laid plans, you still have a few points you can check off right before presenting. They are covered here.

Know your routine

Most Olympic athletes have a routine they religiously perform before each event. Sport psychologists call this ‘mindfulness’ or ‘process focusing’. It's helpful because it focuses the mind on the present moment and so distracts the brain from racing ahead.

During the 2004 Athens Olympics, for example, Australian swim coach Shannon Rollason instructed swimmer Jodie Henry to have a routine for the twenty minutes preceding each race. Swimmers have this amount of time between leaving the change rooms and finally getting on the blocks to race, and it's enough time for nerves and doubts to build. On leaving the change room, Shannon told Jodie she was to speak to someone in the marshalling area; then she was to find the Australian team and wave to them. Next, she had to seek out her parents in the audience and give them a wave. When she was introduced she had to wave and then, and only then, was she to take off her tracksuit and put her cap on. Henry won three Olympic gold medals in the 2004 games using this pre-match routine. Granted, the fact that she could swim faster than anyone else in the pool probably contributed more to her wins than her routine, but in the past her nerves had prevented her from proving this. Having a routine that works for you can certainly help.

The routine that works for you might be as simple as doing a final practice in your head, or listening to a particular song that relaxes you or fires you up.

Visualise success

In an experiment conducted by Australian psychologist Alan Richardson, a group of basketball players was split into three smaller groups. One group was told to practise their free-throw technique for 20 minutes every day. The next group was told to spend 20 minutes every day visualising, but not practising, free throws. The last group was not allowed to either practise or visualise their free throws. At the end of the experiment period, the group who had done nothing remained as they were, but both the other groups showed similar degrees of improvement. The people who only visualised playing basketball were able to perform almost as well as the ones who had actually practised. How can that be so?

Well, the people practising missed some shots. Each time they missed they had, in effect, practised how to miss. The people who were visualising hit every basket, so they were building up the feelings and memory of how to be successful.

Visualisation is an incredibly powerful and simple way of speeding up the improvement process by fooling the mind into believing that you have already done something before you have. Of course, this in and of itself will not turn you into an NBA star, or an inspiring presenter. You actually have to practise as well, but it will help you succeed more quickly.

During the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, for example, the Australian men's rowing team (who were known as the ‘Oarsome Foursome’) had only just scraped into the final. Against all odds, they went on to win gold in the event. They put this down to sport psychologist Jeff Bond, who had worked with them on positive visualisation in the lead-up to Atlanta. They practised the event over and over in their heads — warming up, paddling and finishing the race. Apparently, on the day it went exactly as they had visualised.

You too can use the same technique. In the week leading up to your presentation, picture yourself walking on stage, engaging your audience at the start, going through your key messages, finishing with a lot of applause as you leave the stage and getting all the great feedback afterwards.

Visualising success works because the brain cannot distinguish between reality and imagination. After you have visualised something like this in detail, when you actually stand up to present, your mind feels it's done this before. The more you visualise success, the more you'll trick your mind into thinking it is real.

I must admit I was a bit sceptical of this approach but I have grown to use it and can now say it works. At a minimum, it helps reduce the nerves and anxiety.

Use power posing

Amy Cuddy is a Harvard Business School professor4 who gave a TED talk that has received more than 21 million views to date.5 Cuddy's research links our body language to our hormone levels, our feelings and our behaviour. Her research shows that even faking powerful body postures that convey competence and power can change our testosterone (dominance) and cortisol (stress) levels. Cuddy calls this ‘power posing’ and it can be effective after faking it for only a couple of minutes. With this increase in testosterone and cortisol levels, we increase our appetite for risk and have greater ability to cope well in stressful situations.

IF YOU ACT powerfully, YOU WILL BEGIN TO THINK POWERFULLY, AND WHEN PEOPLE FEEL POWERFUL, THEY BECOME MORE present.

Cuddy believes that our body language can shape who we are, and that the non-verbal gestures we make can govern what other people think and feel about us. Non-verbals can even govern the way we think and feel about ourselves.

If you act powerfully, you will begin to think powerfully, and when people feel powerful, they become more present. They become better connected with their own thoughts and feelings, which can help them to better connect with the thoughts and feelings of others. This can allow a presenter to significantly increase their chances of connecting, engaging and captivating an audience.

During the presentation

If you have prepared like a professional, you have done a lot of hard work leading up to your presentation. During your presentation you should still be mindful of certain things. The following pages outline a few aspects you need to focus on as you present.

Put the audience first

You need to put your audience's needs ahead of yours. Once I was asked to deliver a keynote presentation as part of an internal leadership conference. I was the last speaker of the day. I had to fly to the event so I arrived a few hours early and decided to sit in on earlier presentations so I could weave any themes or messages into my presentation.

It was a glorious spring day in Sydney. The conference room was directly on the water with spectacular views of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. And the best bit was that the conference rooms had floor-to-ceiling glass walls so you could make the most of this amazing view.

However, every speaker who presented was using PowerPoint, so the blockout blinds had to be drawn to avoid the sun glare making it difficult for the audience to see the screen.

During the afternoon tea-break, I was getting my lapel microphone attached and tested along with the other speaker who was on just before me. Someone asked him about his presentation and he said he was not using PowerPoint. I told him I only had provided PowerPoint slides because the organisers had insisted, and I would also be happy to not use them because it would allow the blockout blinds to be raised and the view to be appreciated.

Someone suggested that people may look at the view instead of listening to me. I was happy to take that risk and, at one stage, that is exactly what happened. I was talking away and noticed that quite a lot of eyes were looking past me and out the window. I stopped and turned around to see a large tall ship, with all sails drawn, sailing past directly under the harbour bridge. It was an impressive sight that I commented on. I waited the twenty seconds or so it took to sail by and then continued.

It is easy for ego to come into play here and tell yourself, ‘Everyone should be listening to me’, but it's not about you. It's about them. Keep it real and put your audience first.

Be flexible

Life is never perfect, so things are often going to go wrong. Your presentation time may be cut, the technology may fail, you may be asked an unexpected curly question or you may be interrupted by an audience member who informs you that your topic was just covered by another speaker.

Being flexible in your approach to your content and context will allow you to recover from these setbacks.

A presenter I know, Jane, once had a problem with her slides — they kept randomly moving forwards and backwards, and the remote she was using did not seem to be controlling them. After repeatedly asking the support crew to revert back to the slide she wanted, she decided to ditch them all together and had the support crew turn the system off. Jane found out later that the remotes had been switched between rooms and the presenter in the next room was controlling the flow of her slides.

When things go wrong, the audience has the opportunity to see the real you. How you respond can be critical. Not that you would want something wrong to happen but, if it does, it can create an amazing opportunity for the real you to shine.

It's showtime!

If you want to be engaging and inspiring, you have to treat every presentation like opening night. Even if it is a presentation you have done many times, you need to understand that this is opening night for your audience.

I was once told a story from an interview with Bruce Springsteen. The interviewer asked him how he kept up his motivation to deliver live performances, night after night, after 30 years in the industry. Springsteen replied, ‘It was when I realised that, while for me, every night is a ‘Bruce Springsteen concert night’ there are thousands of people in the audience who have spent their money to see a Bruce Springsteen concert maybe for the first and only time in their lives. They may only come to one Bruce Springsteen concert in their life and I want to give them the best ever Bruce Springsteen experience. And that's what keeps me going night after night.’

So think like Springsteen next time you are about to step on stage and give your audience your own version of a first Springsteen concert (you probably don't need to belt out ‘Born to Run’ … although that would be unusual).

Use your pace

Nothing is more tedious than listening to a presenter stuck on one speed — whether that pace is slow, or super-fast. It comes across as fake or over-rehearsed … a long way from ‘real’. A singular pace can often happen when people read from a script.

Getting your pace right is important, but that also means that you vary your pace at particular points. This helps keep and sustain your audience's attention and stops you developing a monotone.

It's natural that your audience's attention will vary throughout your presentation. Seldom is anyone going to be hanging on every word you say. The harsh reality is you will lose your audience at different points as they zone out — perhaps to think about what's for dinner or if they hung out the washing. So you should give them the opportunity to refocus on you. Varying your pace is an underused technique that helps you do exactly that.

When you are presenting an important point, slow down your normal pace by about 10 per cent — that is, look at your baseline pace and slow it down by 10 per cent. Speaking slowly gives you a sense of authority. Just be careful not to do this too much — otherwise, it will have the opposite effect and you'll come across as patronising, like you're telling a child a bedtime story. Slow down slightly at particular points to increase your presence and impact.

Pausing in between words is also a sure-fire way to have a big impact. This kind of technique signals the importance of what you're saying. Recently I ran a group of leaders through an exercise focusing on this. Without telling them what I was doing I said, ‘What I am about to share with you is really important’. I then remained silently present. I did not say a word for about ten seconds, but maintained eye contact the whole way. Then I asked them, ‘What just happened?’ They responded along the lines of, ‘I just can't wait to hear what you are about to say’ and ‘You had me totally intrigued and had my full attention’.

Just as slowing down and pausing can work to keep or grab an audience's attention, so too can speeding up your pace. If you are sharing an exciting, high-energy point or even a story with lots of action in it, you should speed up what you are saying by at least 10 to 15 per cent. Speeding up recreates the energy and excitement of the story. It's natural to talk fast when we're excited or eager and the aim here is to mimic natural conversational patterns.

Use your space

All the world's a stage.

— William Shakespeare, English playwright

When you are presenting, all your world at that moment is the stage, so use it. Now, of course, every stage will be different — some will be longer, some wider, and they will be different shapes or heights. Regardless of what the stage looks like, make it work for you and take control of it.

You have a lapel microphone on (hopefully) so you are not anchored to the lectern. Get out there and use the stage — but make sure you meander with purpose.

Walking around on stage does a couple of things for you:

- It can create interest and energy.

- It can make you look more confident and feel more confident.

Here are some ways you can meander around the stage with purpose:

- The power position on the stage is front and centre. Use this space to both open and close your presentation and to get across your key messages.

- Move to the front of the stage when you want to get closer to your audience and when you feel you need to make a connection or emphasise a point. When I share a personal story, for example, I always move closer to the front of the stage.

- Move from left to right on the stage to emphasise the past, present and future.

And here are a few further things to consider:

- Make sure you do not walk out of the lighted area. Your audience always needs to see you.

- If there are obstacles in the room (such as columns that block some audience members' view), avoid these spots so the audience can see you most of the time.

- During the sound check, identify any no-go zones where you lose sound or trigger that annoying, ear-piercing screech from microphone interference.

After the presentation

So you may think that as soon as you walk off the stage, your job is done. But it is not. Just as you have things to consider before and during your presentation, you also have things to consider after your presentation.

Thank people

I am not talking about thanking the audience at the end of your speech. That is a given. However, one thing to note is that you should try not to do so with a ‘Thank you for listening’. I try to end with something along the lines of ‘It's been a pleasure being with you’ or ‘Thanks for your energy and interaction; I hope you enjoy the rest of the conference’.

Also showing gratitude to the people who asked you to speak is an important element of presenting. Take the opportunity to be grateful to the people in the audience who came to see you as well as the organisers who invited you to speak.

Small gestures like this can make such a big difference. If you're not already in the habit of thanking people, it may be a good habit to adopt. It doesn't matter whether you've just given a keynote speech, a presentation that you are being paid handsomely for, pro-bono work or a presentation at your team's sales conference — give thanks, because you've been given an opportunity that you should be thankful for.

Seek feedback and reflect

So how did you go? Do a quick evaluation of what worked and what didn't. What should you do more of? What could you do better? I often blog about things as a way to reflect and also to share what I learnt from an experience.

You could use a variety of feedback and reflective models, but I just ask myself three simple questions:

- What did I do well? What seemed to work for the audience?

- What didn't work that I would not use again?

- What could I do differently or better next time?

Also reflect on your presentation through the lens of ‘How real did this feel?’ When did you feel you were being real? When did everything seem to flow? Try to do more of that and your presentations will feel more real — and I can guarantee you, when that happens you start to enjoy them more.

Apart from self-reflection, seeking out feedback from others is also a good idea. You could ask a trusted adviser in the audience how it went. Were people engaged? Sometimes the questions, or lack of questions, after you have presented is also an indicator.

I recall I once went to an appalling breakfast presentation and when the organisers asked for questions at the end, there were none. This is an indication; this is feedback for you as the presenter. Some presenters also record their presentations so they can watch or listen to them afterwards, and pick up the bits that worked and those they could improve on.

It does not matter how you reflect, just make sure you do.

Strive

Besides seeking feedback and reflecting after each presentation, you can do a couple of other things as you strive to be a better presenter:

- Observe other speakers — when you're in the audience and listening to an inspiring presenter, observe what they're doing and be curious about that. What are they doing that makes it such a great presentation? How do they use the stage? When are they sharing their stories? How are they interacting with the audience? Watch some TED talks online and do the same. I encourage you to use your two eyes and ears when watching presenters. One to actually take in what you are hearing and seeing but the other to observe what is happening and what tools are being used.

- Get a mentor — find a mentor to help you develop your content, your style and your confidence. Leaders have coaches for all sorts of things and it's worthwhile considering a mentor to help with your presenting.