Chapter 1

The game has changed

The game we are playing has changed. The way we operated in business twenty years ago, even ten years ago, is different from how we operate today. Significant factors have driven a change in the way leaders communicate and inspire, with the ability to engage and influence now being one of the most important skills someone in a position of leadership needs to possess.

Every day, leaders need to communicate. They need to talk about everything from organisational strategy and values to messages of change. They have to deliver tough and unpopular decisions and they have to communicate triumphs and successes. They have to motivate, engage and excite. They have to ignite.

The reality is that this is becoming increasingly difficult, and skills used in the past are fast becoming redundant. Leaders need to not only be aware of this but also understand why this is happening — so they can then do something about it.

This chapter looks at some of the recent shifts that leaders need to comprehend in order to flourish and grow as leaders.

Understanding generation Y

By 2020, generation Y will make up the majority of the workforce. Many senior leaders I work with tell me that one of their biggest challenges is to manage and lead generation Y. But, as John Stuart Mill (an English philosopher and economist) once said, ‘That which seems the height of absurdity in one generation, often becomes the height of wisdom in the next’.

Generation Y includes people born between 1980 and 1995 (although some ranges include people born as late as the early 2000s). The label of generation Y followed on from the previous generation's label of generation X, and while this seems to be the label that has stuck, this group is often also referred to as Millennials or the ‘dot-com’ generation. (If you're wondering why the labelling for generations went from ‘baby boomers’ to ‘X’, it's due to Canadian author Douglas Coupland, and his book Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. The book was ironically about a generation that defied labels by stating ‘just call us X’.)

Over the past few years, comprehensive studies have shown how generation Y is different from previous generations. For example, Deloitte's third annual Millennial Survey, conducted in 2014, polled nearly 7800 members of generation Y from 28 countries. The findings of this survey outline the significant challenges that business leaders face when trying to meet the expectations of generation Y.

Key findings from the survey showed generation Y valued these features in organisations they worked for:

- Ethical practices — 50 per cent of those surveyed indicated that they wanted to work for a business with ethical practices.

- Innovation — 78 per cent of respondents said they were influenced by how innovative a company was when making employment decisions. Most said their current employer did not encourage them to think creatively. They believed the biggest barriers to innovation were management attitude (63 per cent), operational structures and procedures (61 per cent), and employee skills, attitudes and (lack of) diversity (39 per cent).

- Nurture of emerging leaders — over 25 per cent of respondents indicated that they were ‘asking for a chance’ to show their leadership skills. And, 50 per cent believed their organisations could do more to develop future leaders.

- The ability to make a difference — they believed the success of a business should be measured by more than just its financial performance, and argued a focus on improving society was one of the most important things a business should seek to achieve.

- Charitable acts and participation in ‘public life’ — 63 per cent of respondents indicated that they donated to charities, while 43 per cent actively volunteered or were a member of a community organisation, and 52 per cent had signed petitions.

In 2013, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) in conjunction with the University of Southern California and the London Business School published their results of a two-year global generational study called PwC's NextGen: A global generational study. With more than 44 000 people participating, the results are similar to those found by Deloitte, and also offer valuable insights for leaders and organisations keen to understand what makes generation Y tick.

According to the findings from the study, generation Y:

- value work–life balance, with the majority of respondents saying they were ‘unwilling to commit to making their work lives an exclusive priority, even with the promise of substantial compensation later on’

- place a high priority on the culture of the workplace they choose, wanting to work in an environment that ‘emphasises teamwork and a sense of community’

- value transparency (especially in relation to decisions about their careers, compensation and rewards)

- want to provide input on their work and how it is assigned, and openly seek the support of their supervisors

- expect their contributions to mean they are supported and appreciated, and want to be part of a cohesive team.

PwC highlighted that, while all of the preceding statements are also true of other generations, it's not to the same degree. For example, 41 per cent of generation Y would like to be rewarded or recognised for their work on a monthly basis (if not more frequently), whereas only 30 per cent of other generations ask for this kind of frequency.

Generation Y isn't going away and judging them will not help. We need to understand them, and adjust the way we lead them accordingly, in order to lead organisations that flourish.

They have great expectations

Generation Y wants to be challenged; they want to be inspired and they will not accept the status quo. It's this innate sense of curiosity and their ability to question tradition that has given them the moniker ‘generation why’.

With so many options available to this generation, if leaders are not providing a workplace that challenges and inspires them, they will seek to work somewhere that does.

I was recently talking to a member of generation Y called Robert. Robert is about 30 and works for a large corporation. He was sharing with me the experiences of his latest performance development conversation. In the corporation he works for, employees are asked what job they would like to be doing in five years' time. Robert thought this was a stupid question because the job he will most likely be doing in five years' time doesn't even exist yet. This mindset is very common for this generation, and while this kind of thinking may be exciting for them, leading such creative employees, whose working lives seemingly don't have the boundaries we once had in traditional business, can also be very daunting.

This generation has different expectations and beliefs about what they want out of work from their employers. Yes, they want to achieve and be rewarded financially but it is not just about that. They are looking for greater fulfilment, more personal development and opportunities to cultivate a more well-rounded life. More importantly, they genuinely want to make a difference and, therefore, they take corporate responsibility very seriously.

Aaron is an example of this. He is a lawyer who worked for a global consulting firm for five years. The incentive for the long hours that came with the role was the possibility of a very highly paid job. But he told me that he came to realise that nothing about the senior partner's life was attractive to him. Yes, they earned a lot of money but he decided he wanted more than that. He is still a lawyer but now works for a company that has a purpose that he fully believes in.

Companies and leaders need to find ways to meet the demands of this generation's expectations or they will risk losing them.

They are loyal

Due to their tendency to change companies at a much faster rate than previous generations, generation Y has at times been unfairly labelled as disloyal. However, they are simply responding to the environment they were raised in. Many members of generation Y saw their parents lose their jobs in the recession of the late 1980s and early 1990s after decades of service. After witnessing the fallout from this job loss, they are not inclined to provide the same level of loyalty to companies that their parents did. When their earliest exposure to the business environment taught them that world offers little job security, can you blame them for changing roles more frequently than previous generations?

However, just because they are more likely to change employers (the average employee tenure in 1960 was fifteen years; today it is four), this should not been seen as a sign of disloyalty. Gen Ys are loyal. They are loyal to friends and they are loyal to brands. You only have to be outside an Apple store the day before a new iPhone is released to see evidence of this loyalty in the queues that snake down the street and around the block.

Leaders need to make generation Ys feel valued. They need to be more inclusive and transparent in the way they communicate and lead. They need to provide more regular feedback to this generation than they provided to previous generations. They need to be more real. This generation is screaming out for leaders to be more real — and they are getting a lot of support from the members of other generations, who see the value in people who lead with authenticity and transparency.

So generation Y can be loyal. Leaders and companies just need to work harder to earn their loyalty by offering a combination of tangible, real-time rewards, open lines of communication and transparency. The long, distant promise of promotions and job security does not rate for generation Y.

They want to have fun

Generation Y employees expect to enjoy their job. The thought of staying in a job they hate is absurd to them, and you really can't blame them. A mindset of ‘If you're having fun you can't be working’ will not serve you well if you are leading this generation.

When it comes to having fun at work, I think we can learn some important lessons from the Danes. Many words exist in one language and not in another language. One such word exists in the Danish language but not in English — ‘arbejdsglæde’. ‘Arbejde’ means ‘work’ and ‘glæde’ means ‘happiness’, so ‘arbejdsglæde’ is ‘happiness at work’. This word also exists in the other Nordic languages but does not exist in any other language group.

On the flip side, the Japanese have ‘karoshi’, a unique word that translates to ‘death from overwork’. Not surprisingly, no such word exists in Danish. Nordic workplaces have a strong focus on making their employees happy. Danes expect to enjoy themselves at work, and why shouldn't you too? Your employees are catching on to this train of thought and so have increasing expectations that their time at work should be enjoyable.

GENERATION Y CAN BE loyal. LEADERS AND COMPANIES JUST NEED TO WORK HARDER TO EARN THEIR LOYALTY BY OFFERING A COMBINATION OF TANGIBLE, REAL-TIME REWARDS, OPEN LINES OF COMMUNICATION AND transparency.

As a leader, you don't have to turn into a stand-up comic, but thinking that you can't have fun at work is misguided and, I would argue, not realistic. This approach normally comes from a leader who is perhaps trying to be the serious leader they think they are expected to be. Being a strict, staid boss is an outdated concept. Being more relaxed and open to the concept of fun is more real and gives you a greater chance of connecting and engaging the hearts and minds of the people that work for you.

They are smart cookies

Generation Y is the most formally educated generation ever. Education rates in Australia have been on the rise for decades and this means much of the power has shifted to employees.

Unlike previous generations, members of generation Y don't feel the need to work in an organisation for years before they ask for a change of role or promotion, or increased work–life balance. They know what they expect and demand these aspects from their first day at work — many will run through their expectations during the interview process. I know of one graduate who had interviews with three of Australia's largest corporations. While these corporations were interviewing him, he was also interviewing them. He received offers from all three but he chose the company that had the greater commitment to volunteering in the community through their skilled volunteer program.

What companies offer employees and how they lead will have a significant impact on not only the retention and attraction of generation Y staff but also how well their employees perform.

This is backed up by further studies. For example, the 2006 McCrindle research paper, New Generations at Work: Attracting, Recruiting, Retraining and Training Generation Y, states: ‘The findings are clear: unless their direct supervisors and the leadership hierarchy manage in an inclusive, participative way, and demonstrate people skills and not just technical skills, retention declined’.

The research further stated that, ‘Their preferred leadership style is simply one that is more consensus than command, more participative than autocratic, and more flexible and organic than structured and hierarchical’. This means generation Y wants managers who talk openly with them and value their input, and an environment where all staff members are kept in the loop.

Avoiding information fatigue syndrome

In 2010 Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, stated, ‘There was 5 exabytes of information created between the dawn of civilization through 2003, but that much information is now created every 2 days’. Schmidt's figures have since been questioned (one expert writing in 2011 said a more accurate comparison would be that 23 exabytes of information was recorded and replicated in 2002, and that in 2011 we recorded and transferred that much information every 7 days.) However, the main point remains the same — humans are creating, transferring and storing an incredible amount of information every day.

Information fatigue syndrome (IFS), or information overload, occurs when we are exposed to so much information that our brains simply have trouble keeping up with everything. When the volume of potentially useful and relevant information available exceeds processing capacity, it becomes a hindrance rather than a help — and is when we start suffering from IFS.

Information overload has been around for a while and we are certainly not the only generation to experience it. In fact, in the very first century Seneca said ‘distringit librorum multitudo’, which means ‘the abundance of books is distraction’.

With the ground-breaking invention of the printing press (along with other factors), books started to become more mainstream from the 17th century and this led to concerns. French scholar and critic Adrien Baillet wrote in 1685, ‘We have reason to fear that the multitude of books which grows every day in a prodigious fashion will make the following centuries fall into a state as barbarous as that of the centuries that followed the fall of the Roman Empire’.

Today, we are experiencing more information overload than our ancestors ever did. To put things in perspective and gain further information about information overload, go to digitalintelligencetoday.com and search ‘information overload’. On the ‘fast facts’ page, you'll find that information overload can lead to short-term memory loss, greater stress and poor health. You can also find stats such as that, on average, Americans consume 12 hours’ worth of information and send 35 texts per day, and spend 28 per cent of their work hours dealing with emails. Information overload can also lead to short-term memory loss.1

So what does this all mean for leaders?

Herbert Simon (1916–2001), an American scientist and economist, is most famous for his theory of ‘bounded rationality’ and its relationship to economic decision-making. In describing his theory, Simon coined the term ‘satisficing’ — a combination of the words ‘satisfy’ and ‘suffice’.

Simon's theory is based on the premise that people cannot digest or process all the information required to make a decision or take a course of action. He believes that not only are people physically not able to access all the information required but also, even if they could access all the information, they are unable to process it.

Simon labelled this restriction of the mind ‘cognitive limits’ and it is these limits that mean we seek just enough information to satisfy our needs. For example, when you are looking for accommodation for your next holiday it is almost impossible for you to find out about every form of accommodation available. You may look at three or ten places and then make a choice based on that information you have deemed to be ‘enough’.

An overabundance of information actually makes it harder to get people's attention — or, as Simon expressed it, ‘A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention’.

In business, we tend to add to this overload of information. We send countless emails when having a conversation with someone would be more effective. We CC and BCC people in on emails constantly and a lot of the times unnecessarily — we do so for our purpose only, not theirs.

We can't stop this avalanche of information but we can make a conscious effort not to contribute to it. We could stop waffling on in meetings and presentations and focus on the key point — how do we get cut-through. Employees are overloaded with information, so leaders need to communicate succinctly and with brevity to cut through this and have impact.

Working with six degrees of separation

No doubt you've heard the term ‘six degrees of separation’, in common usage following the release of the popular movie of the same title back in 1993. The film was actually adapted from a play that was inspired by the real life story of a conman who convinced a number of people that he was the son of actor Sidney Poitier.

The premise of the six degrees of separation theory is that everyone on the globe is connected to any other person on the globe by a link of no more than six acquaintances. So, in reality, you are no more than six introductions away from the President of the United States, the Queen of England or the Pope.

EMPLOYEES ARE OVERLOADED WITH INFORMATION, SO LEADERS NEED TO COMMUNICATE SUCCINCTLY AND WITH BREVITY TO CUT THROUGH THIS AND HAVE impact. BEING REAL AND COMMUNICATING AUTHENTICALLY CAN ALSO HELP YOU GET CUT-THROUGH.

In 2008, researchers at Microsoft announced that this theory was correct. They studied more than 30 billion electronic conversations among 180 million people across the globe and worked out that any two strangers are (on average) distanced by precisely 6.6 degrees of separation.

Some say that this concept was linked to the initial thinking behind social media sites. This may or may not be true but what we do know to be true is that the rise of social media has reduced the degrees of separation even further. In 2011, scientists at Facebook and the University of Milan reported the average number of acquaintances separating any two people in the world was not six but 4.74. The experiment took a month and involved all of Facebook's 721 million users.

Furthermore, a study of 5.3 million Twitter users found that, on average, 50 per cent of people on Twitter are only four steps away from each other while nearly everyone is only five steps away.

LinkedIn is set up on only three degrees of separation, in that when you connect with someone:

- you already know them

- you know someone who knows them

- you know someone who knows someone who knows them.

LinkedIn is not just about the degrees of separation, however; it's also about creating opportunities to connect with other people. At the time of writing this chapter, I had 1204 LinkedIn connections (these are people that I already know); from these connections there are 577 247 people someone I am connected with knows, and more than 12 million people who know someone who knows someone who knows me.

So what do these shrinking degrees of separation have to do with being more real?

Well, besides hearing about six degrees of separation, you may have also heard the phrase ‘It's not what you know, it's who you know’. To a certain degree this is correct but now it's not about what you know, and it's not really about who you know — it is about who knows you.

Have you ever had someone come up to you and say ‘Hi’ in a very familiar way? They clearly know you but you have zero recollection of who they are. They then may pick up on this and say something like, ‘We met at the Innovation conference last year’. At that point, you may fake remembering them or apologise, stating that you met so many people at the conference that it is all a blur. The reality is that you may have met hundreds of people at that conference and you may not remember them all, but you do remember some. You remember the ones who had an impact on you. The ones who said or did something that resonated with you or something that was a bit different; the ones you had a conversation with that stood out from the other hundreds of conversations you had. And all because that person or that conversation was probably a lot more real.

The same can be true for you. You may meet someone at an event and six months later you have a need to contact them — perhaps for a job, for advice or to share your new product and services. Because you have met them — perhaps you even swapped business cards at the event — you feel confident that you can contact them directly. However, when you make contact with them, they do not remember you. Yes, you may have met them but if you did not make an impression, they will not remember you.

Dan Gregory, CEO of the Impossible Institute, speaker, author and panellist on the Australian TV show The Gruen Transfer, talks about the importance of striving for professional fame. In the book he co-authored with Kieran Flanagan, Selfish, Scared and Stupid, he argues that positioning is more important than what you have done, and that the professional fame you build determines your success because, above all else, fame opens doors.

Imagine your busy life. Work is hectic, you have a big presentation on tomorrow and you need to take your kids to hockey practice. In this midst of all this, you get a call from somebody you have never heard of who wants to catch up with you for a coffee to pick your brains about your area of expertise. You may make time, you may not. Now, imagine if Richard Branson rings and wants to pick your brains. I'm figuring the kids are making their own way to hockey practice!

I work with many leaders who, at various stages of their career, have had to reach out to a whole lot of people in their network. I ask them to write down all the people they know in the target audience that they are trying to reach. Then I ask them to highlight the ones who know them. Not just those who have ‘met’ them but those who know them. Really know them. The people who would stop and say ‘hi’ and call them by their first name if they passed them on the street. Try this yourself when thinking about the people in your network. Unless you can confidently say that is what would occur, you really don't know them and they really don't know you, regardless of how many times you have met.

Also, you may never have met a person but they could still know you or know of you. And if someone does know you, or know of you, without ever having met you, that is more powerful. I often have clients come to me and give me a name of someone who has referred them to me and I do not know this person at all.

The more real you are, the more likely you will have a greater impact when you meet people, the more they will remember you and know you. The more people who know you, the more people will be talking about you and so the more people will hear about you. Being known by many has a ripple effect and increases your professional fame. Your knowing people does not. So instead of striving to know people you should aim to be known by many people.

BEING KNOWN BY MANY HAS A RIPPLE EFFECT AND increases YOUR PROFESSIONAL FAME. YOUR KNOWING PEOPLE DOES NOT.

Three brains are better than one

Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all

— Aristotle, Greek philosopher

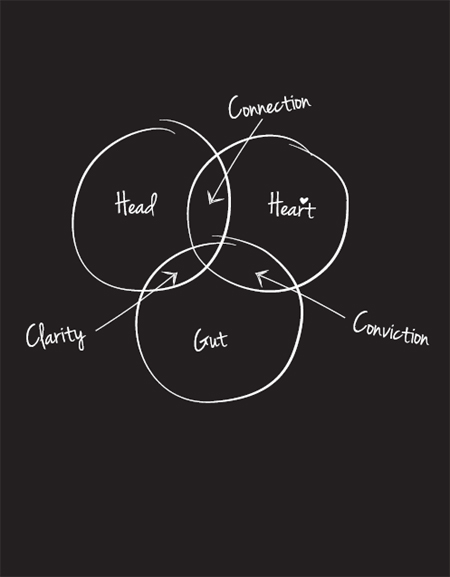

You may be familiar with the expression, ‘Two brains are better than one’? Well, imagine if you had three. The good news is you do. Neuroscientists have discovered that we have three independent brains in our body. One in the head, one in the heart and one in the gut. Each involves complex neural networks, completely independent of each other and with a different purpose and function from the other.

Neurocardiology research by Dr Andrew Armour showed that the heart has a complex neural network containing neurons, motor neurons, sensory neurons, interneurons, neurotransmitters, proteins and support cells. The complexity of this network allows it to qualify as a brain. His research also showed that the heart's neural network allows it to operate completely independently from the brain in the head, and that it can learn, remember, feel and sense.

Further research by neurobiologist Dr Michael Gershon discovered the brain in the gut. His 1998 book The Second Brain described the brain in the gut as the ‘enteric’ brain, consisting of more than 500 million neurons that send and receive nerve signals throughout the torso, the chest and organs. This ‘enteric’ brain utilises every class of neurotransmitter found in the brain located in our heads and, just like the brain in the heart, it can learn and remember and process information independently.

So while the brains in the heart and the gut may look different to the brain in the head, they are brains none the less.

The impact of this research is significant to all aspects of our life. Our relationships, our health, how we make decisions and how we communicate are all influenced by our three brains. The research has given birth to a whole new focus within leadership development programs, where leading companies are developing leaders in self-awareness so they can lead from the head, heart and gut.

In their book mBraining, Grant Soosalu and Marvin Oka explore how the three brains affect leadership behaviour. Their findings show that each of the brains has three core primary functions.

The heart brain is responsible for:

- emoting — processing emotions such as grief, anger, joy and happiness

- values — what is important to you and your priorities as well as the relationship between your values and your dreams and aspirations

- relational affect — your connection to others and how you feel, such as love or hate, caring or uncaring.

The gut brain is responsible for:

- core identity — a deep and visceral sense of self

- self-preservation — incorporates self-protection, safety, boundaries, hunger and aversions

- mobilisation — focuses on mobility, taking action, having gutsy courage and the will to act.

The head brain is responsible for:

- cognitive perception — cognition, perception and pattern recognition

- thinking — reasoning, abstraction, analysis and meta-cognition

- making meaning — semantic processing, language, narrative and metaphor.

Each of the brains in the head, the heart and the gut is fundamentally different, with different concerns, different competencies and different ways of processing what is going on in the world around us.

Soosalu and Oka explore the significant impact this has on leadership, and especially on decision-making. They believe it is critical for all three forms of intelligence to be accessed when making decisions. Without the head intelligence, the decision will not have been properly worked through; without the heart intelligence, the emotional connection and energy will not be sufficient to care or prioritise the decision; and without the gut intelligence; attention to risk, or even the willpower to act on the decision, will be insufficient. The illustration on page 21 shows how your three brains can interact.

If accessing the wisdom of the three brains is essential for leadership, it should come as no surprise that many leadership programs now focus on the concept of using the head, heart and gut when making decisions.

In their book The Practice of Adaptive Leadership, Marty Linksy and Ron Heifetz also emphasise the important role that the head, heart and gut play in leadership. Their mantra is that technical leadership is above the neck (from the head), and adaptive leadership is below the neck (from the heart and gut). In May 2014 I had the great pleasure of spending just over a week with Marty and Ron at the Harvard Kennedy School of Executive Education, where I attended their Adaptive Leadership program.

As a warning to you, my time at Harvard had a profound impact on me. I learnt a tremendous amount about adaptive leadership and experienced much professional and personal growth. The insights I gained from this program have heavily influenced the content of this book so I reference my time at Harvard quite a bit. People who know me personally are sick of me talking about Harvard … not that it stops me!

In the classrooms of Harvard I spent eight intense and long days with sixty-seven fellow students from around the world, all drawn together in a vessel where the heat was deliberately raised in order for us to explore and practise adaptive leadership.

Understanding how to use your three brains to make decisions is critical for leaders, and knowing how to communicate in a way that is directed at the three brains is just as critical. Too often in business the way we communicate is directed only at the brain in the head. Communication around change (regardless if it's major organisational change, a new strategy or even a minor change) is often communicated in a very logical way — this is why we need to change, this is what we are going to do, this is how we are going to do it and this is how we are going to measure it.

When we appeal only to the brain that processes the logic of the change, and do not appeal to the brain that is responsible for values and connection or the brain that is responsible for mobility and action, our chances of actually achieving what we want to achieve are significantly diminished.

The way we describe failure or non-action gives us clues to this. Doubts like ‘I know it makes sense but it just does not feel right’ are telling us that while the brain in the head has processed it logically, alarm bells are going off in the brain in the gut.

Other statements like, ‘He didn't have the guts to do it’ or ‘His heart just wasn't in it’ also point to the critical roles the brains in the heart and gut play when it comes to action and success.

When I work with someone who wants to know if they are a great leader or not, I ask them a simple question: ‘When you look over your shoulder is there anyone following you?’ To be a leader you need to have followers and to have followers you need to be able to connect, engage and inspire them to come with you. To do this, you need to be able to connect with all three brains and to be more real.

Note