What are scenarios?

Have you ever stopped to consider how your library would function without:

It is very difficult to imagine our present world without these three fundamental realities and yet only ten years ago, such things were just emerging. Imagine what the future might offer us … ten years from now.

When we talk of our individual plans for a holiday or a career, we are constructing future stories. Stories are the precursor to action. They help us to describe what might be. Imagine that you were able to re-invent your library’s future. What would you do? Would you know what to change? Would you be able to convince your stakeholders and your colleagues about your proposed changes? Would you be confident to select just the right changes?

It is important to recognise that we develop a lot of stories before settling on an actual action plan. And so it is with scenarios. We should be developing a number of stories about the future of libraries. There are many possible stories about our organisations. Many cultures have passed their stories through their oral culture. In a similar way, other cultures have recorded their story on stone, papyrus or paper. These are historical stories. We will in this book be developing imaginative stories about our future – not our present or past. We just do not recognise that these stories exist or that these stories can be quite different from the present style of operation.

Stories are vastly underestimated as a tool for understanding the power of cultures and possibilities. Oral cultures use stories with great skill to perpetuate, even reinvigorate, what it means to belong to that particular culture. The stories sustain everything that it means to belong to and understand the culture and its history. Just as each family has stories of its past, its members and all their aspirations, so do our libraries. Libraries have stories about how they have done well and the impact which they have had. Living in the library culture as we do, we often tend to believe without necessarily questioning the nature and veracity of those stories. We have heard that libraries are ‘at the heart of our organisations or communities’; we have heard that libraries are the only organisations that can deliver information; we have heard or learnt that publishing is the only way in which information can be presented as literature or factual information. These are stories which we accept, often without questioning. This book is committed to cultivating new stories about libraries and librarians.

Scenarios, which are stories that are constructed with informed views and knowledge, will be developed by the readers of this book using described techniques and approaches. These scenarios will be stories of possibilities; not rejecting the past, but clearly allowing and cultivating new possibilities. Scenario Planning is what we need to be engaged in prior to this action. We need to allow for the fact that we have choices which can be articulated through stories, and where each of these stories can be considered as potential futures, before deciding on the future direction of our libraries. But in all of this we need to use our imagination, informed by knowledge of our profession, the industry we work in and the future, or futures, that beckon us.

The future is not linear

We were making the future, he said, and hardly any of us troubled to think what future we were making. And here it is! (H.G. Wells)

The future is often seen on a continuum with the present, in a linear relationship, as a simple extension of the present. We often expect that what we do today will be different to what we do tomorrow; but not so radically different. In this articulation of the future we are powerless to affect it. We believe that it will just happen. A linear view of the past, through the present then into the future is not a forward-looking continuum but rather a backward-looking expression. This is achieved by looking from the future and imagining that our path to this position has been entirely linear. The linearity is an imposition on history to explain events, to set them in a context and to present it as being the best way to reach that point in time. It is useful to note the concept of linearity as we will then remember that the history we lived through is riddled with decision points; points or times when decisions are made which will directly affect that future. If we remember those collective decision points we will easily see that the path to the future is not straight or linear.

It is difficult to imagine how we can improve on our present ways of doing things. We can visit an art gallery and view many forms of artistic expression and think silently to ourselves: ‘Well, that is interesting. I cannot imagine any better ways to express feelings, emotions and views of the world than what I have seen today in this gallery collection.’ The range of human emotion, imagination and perspectives on our world is incredible. As each age throws up new interpretations and insights into the human condition, these insights can often contain the germs of new approaches, of different ways in which to respond to challenges confronting a society, an organisation or even a culture. As an aside, it is widely recognised that sometimes the most insightful and different artistic expressions have come through psychotic episodes, or mental illness. Artists ‘see’ the world differently. They can represent the world through their imagination and enable us to begin to ‘see’ what they ‘see’. Their art will often give the viewer an entirely different view of what is being represented.

How ignorant of the future we are, and how emotional when it arrives and fails to conform to expectations. (Peter Bernstein1)

We can see our favourite sporting individuals or teams perform at the heights of kinetic excellence, achieving feats of sporting prowess which we cannot imagine being bettered. Their training methods have led to world records; have led to feats of endurance which have been unsurpassed. It is almost impossible to predict how fast people can run, how fast they can swim, how much they can endure, or how a team can dominate its opposition in such a spectacular and generation-shattering manner. In these areas of kinetic intelligence we are confronted with excellence pushing the boundaries of what we thought was possible. In other words, we are forced to accept that what we thought was not possible is now not only possible but is a reality.

What is the value of scenarios?

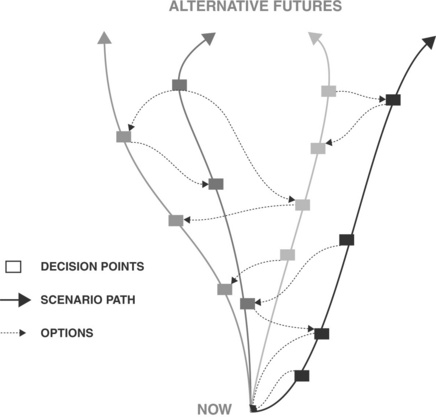

![]() Scenario planning generally identifies a number of scenario paths leading to alternative futures.

Scenario planning generally identifies a number of scenario paths leading to alternative futures.

![]() Each scenario has points in time when decisions must be made to continue or move onto another path (options) based on what is learnt and what has changed.

Each scenario has points in time when decisions must be made to continue or move onto another path (options) based on what is learnt and what has changed.

![]() Ability to move onto another path (number and type of options) depends on the path you are on and the type of internal and external factors influencing that move.

Ability to move onto another path (number and type of options) depends on the path you are on and the type of internal and external factors influencing that move.

The future impacting on libraries

The Internet was only recently a concept in the mind of Tim Berners-Lee and is now a reality which has been earth-shattering in its impact. But what will its impact be beyond the present? The Internet came on the practical horizon in the early 1990s and we puzzled over this set of computer network connections that were almost like neural connections in our minds. The connections grew and grew and became more and more complex. In the early stages, we would never have had an appreciation of how the Internet would impact on the way we communicate and deliver services and information. We started to communicate with each other via e-mail and very quickly we have become dependent on this mode of communication. We then started to see applications which were previously local only but are now being beamed much more widely into the global audience. From a library perspective, this development facilitated the sharing of library catalogues, the data in them, the digitisation and sharing of library resources, the evolution of the e-journal article, the delivery of digital items direct from supplier to client without the intervention of the library staff at all and the Open Access movement.2 The Internet clearly is having a profound effect on the world, the way in which we do business, the way in which we relate to each other and the way in which we deliver services and content. Joshua Meyrowitz famously used the phrase ‘No sense of place’ to describe the impact of electronic media on social behaviour. He might have also used the phrase to describe the impact of the Internet on libraries.3 The Internet is sharply changing our organisational structures and services. Real estate agents now conduct far fewer home visits but have the house open across the Internet. Libraries are having their content much more available on the Internet and need new skills and staff to achieve this. Our organisations are being re-shaped, our staff re-skilled or new types of staff employed.

As libraries and information services are inextricably caught up in this maelstrom swirling around us, it is difficult to see the world outside the whirlpool as the changes seem to be constant. In fact, the only constant we have is change. If from a planning point of view change is a constant, it is so easy to see how our library and information service staffs find it wearing, find it frustrating, find it almost overwhelming at times. The reaction to change from staff can be a passive aggressive stance, which is understandable if they cannot be involved in the planning, even at the perimeter, and simply have change thrust upon them.

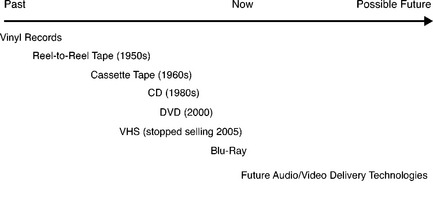

Another challenge of our modern lives is to deal with and relate to other aspects of technology. We have moved so quickly in our lifetimes from the hard disc vinyl records to the reel-to-reel tape, to the cassette tape, to the CD, to the DVD and now to the digital. The digital format and delivery have become dominant for all forms of contents. We have seen communication formats squeezed into these new vehicles for communication. Music was the first and the easiest; movies were more difficult but have now moved and are being delivered in the DVD format, which is itself undergoing changes in its technology. Journal content has moved from the print page quickly through the CD, the juke box and now into the virtual. The mainframe computer was quickly overtaken and superseded by the power and empowerment of the much preferred personal computer, where individuals were able to work in their own personal space and now via wireless to be creative, to be productive and to be less and less dependent on existing work structures. We have seen technological devices develop from the transistor radio, to the Walkman which used cassette tapes, to the iPod and now to the ubiquitous mobile phone. The impact of technology cannot be underestimated. The availability and appropriateness of a technology can, if allowed, change the essential ways in which we conduct our business. One example of this which is currently in vogue is to access the library’s online catalogue from the mobile phone so that time spent in the library is minimised. Mobile devices for information access are still to reach this zenith of popularity.

Marshall McLuhan, the Canadian cultural and media guru from the 1960s, ascribed to electronic media the capacity to shape the culture and politics of our time. Different media would be embracing of change while others would be more remote. McLuhan saw that the power of each medium would impact on all who come to use that medium. So the Gutenberg printing press created the capacity for individual study in isolation and for ideas to be transmitted so much more easily. McLuhan believed that we should have a rear vision mirror view of history in our lives. He meant that we always see the present in terms of our past and he believed that because of this we are not able to deal with the future until it happens to us. Marshall McLuhan inspired many to look at the electronic media in our lives in a different way. He saw technology as a determinant of social arrangement and change. If McLuhan achieved anything it was to highlight the impact which communication media have on social communication and interaction. Libraries have always been impacted by technology over the centuries, especially now and certainly into the future.

We read widely that the role of the physical library is being directly influenced by the technology which libraries have embraced to deliver content to their users. This technological impact has led to the suggestion that libraries are largely irrelevant, even obsolete. These claims are often supported with the view that it is only necessary to organise the digital connections and all else is irrelevant. Yet we are seeing a revitalisation of libraries as social spaces where information and creativity interact. It is a renaissance. But where is this movement going? Is it a new strategic direction or purpose? What will be the impact of the next technological development on the physical library? What will be the impact of this new type of library space on the nature of the library service? Where will the vast legacy collections4 be located and how will they be made available? Perhaps these changes are just happening without intentional purpose or direction.

Earlier in this chapter we began to look forward and found that there are limits to our imagination and that we think about the future as a linear extension of the present and the past. Often, the future is seen either as a series of crises or as the utopia. The Chinese language has a word called Wei Ji which means crisis. Literally this Chinese word has two components: Wei meaning danger and Ji meaning opportunity. For every future, Wei Ji is probably a very appropriate term or descriptor. Too often we are beguiled by the danger in a situation and confused by or blinded to the opportunity. Uncertainty of purpose and the lack of clear direction both contribute to this sense of crisis. The use of Scenario Planning as a set of tools enables us to begin to deal with the opportunity.

What is the future and does science fiction predict the future?

The concept of the future can be described on a continuum from the past through to the present. This, of course, is a simplistic if not overly simplistic description of a concept which has held writers and thinkers in awe for an eternity. There has long been a fascination with the future, in knowing what could be, what will be and, by inference, influencing the outcomes through foreknowledge. The concept that there is a linear relationship between the past and the future is also a misconception. It is popular to describe ‘progress’ as moving our society from one point to another along a preordained path of development. Yet history does not move in straight lines; developments in our society are not linear either. The future is achieved through spates of discovery or innovation and unexpected paths of development. The future can also be regressive, and thus is very hard to predict.

The unpredictability of the future can be seen in such disasters as the Cambodian Pol Pot regime, where civilisation clearly regressed into a terrible form of savagery; the potent advances with stem cell research hold us spellbound as they threaten to solve so many genetic disorders and promise cures for previously unsolvable human conditions. Technology is often seen as the saviour of our society, leading it to bigger and better things. But often, the creation of new technologies leads to great sadness and despair. The advent of nuclear technologies simultaneously holds both great hope and despair. Great hope as a ‘clean’ environmental force delivering energy but despair in that there is no way of controlling the waste and in the hands of malevolent forces it could cause untold harm and misery. So ‘progress’ does not hold good or indeed bad values; in other words it is neither good nor evil. It is the use to which a development is put which dictates its moral perspective.

This discussion highlights that new technologies and new developments are not necessarily good or useful. They are not manichean! It is the uses to which they are put which will determine their value. Technology alone cannot be relied upon for good outcomes in our libraries.

Science fiction literature in the Western tradition has been rich and laced with imagination about the future. Writers such as H.G. Wells invented time machines to transport us physically into other worlds, while also creating adventures which were spectacular and enthralling and giving us a new way of looking at the future. In many ways Wells predicted some aspects of the future and stimulated our imagination for what could be. His classic book War of the Worlds built on existing knowledge of other worlds, yet created a whole new genre of possibilities and technologies. An article in the New Scientist5 asked ‘Whether science fiction is dying’. One commentator suggests that we are living the future of science fiction. ‘The most useful thing I’ve learned from science fiction is that every present moment, always, is someone else’s past and someone else’s future.’6 A crucial understanding in scenario creation and planning is that there are many views which usefully contribute to new understandings. There is no such thing as perfect knowledge. The economic concept of asymmetric information7 describes the observation that some people know more about some things than other people. In many senses this is an unremarkable observation and yet there is a very significant literature surrounding this economic thought. To some extent it is possible to arrive at average views or moderate views by trying to accommodate everyone’s views. In Scenario Planning we need to draw on as many views as possible but not to ‘dumb them down’. It is important to keep as many views as possible on the table through the process. James Gunn’s ‘Libraries in Science Fiction’8 relates how the concept of the library has, for the most part, been fictionalised as the human brain in various science fiction classics. He recounts how the human brain is seen as a ‘library’; retrieving knowledge and information and making the connections. The significant books in this view include Robert Heinlein’s Universe (1941), David H. Keller’s The Cerebral Library (1931) and Jorge Luis Borges’s The Library of Babel (1956). The conceptualisation of the library in science fiction literature, as we might know it, provides quite a different view of what a library is and what it means to have a library. Or does it? Perhaps this is one scenario of what could be.

Change

Barack Obama is quoted as saying: ‘You can’t stop change from coming … you can only usher it in and work out the terms. If you’re smart and a little lucky, you can make it your friend.’10 We have much evidence of the amount of change which our current society is experiencing.

Marshall McLuhan once famously described his work as ‘difficult stuff’. He was referring to his theorising about the impact of media on our lives and the ways in which it shapes our society. His adage, ‘the medium is the message’, became famous in the 1960s and 1970s. While he did not live to see the Internet begin to dominate our social and commercial communications, there is no doubt that he would have had strong and meaningful insights into the impact it would have.

An initial view of the Internet

The best place to start when considering the Internet is to realise how radically different it is as a medium. Marshall McLuhan was correct when he said: ‘The medium is the message’:

The medium is not only the message. The medium is the mind. It shapes what we see and how we see it. The printed page, the dominant information medium of the past 500 years, molded our thinking through, to quote Neil Postman, ‘its emphasis on logic, sequence, history, exposition, objectivity, detachment, and discipline.’ The emphasis of the Internet, our new universal medium, is altogether different. It stresses immediacy, simultaneity, contingency, subjectivity, disposability, and, above all, speed.11

This is the most important aspect to remember about the Internet and our future libraries: the technologies we use shape the way we operate and how we relate to each other and our users.

As cited by John Markoff,12 the number of publicly available Internet pages has risen in just ten years from 3.5 billion pages in 1999 up to over 30 billion pages in 2009. The number of hosts on the Internet in 2007 was 433 million. The number of private Internet pages is a multiple factor of this. The current mode of vanity publishing is the blog and, according to Technorati’s State of the Blogosphere 2009,13 more than 133 million blogs have been tracked by them since 2002. While the value of information available through the Internet is overwhelming, many of these pages reach the public area only through subscription. They include billions of pages of journal articles, e-books, and reference works available through powerful library services. The rates of growth of these indicators do not show any signs of slowing down. This phenomenon is often described as information glut or overload. But overload is fast becoming even more complex. An additional overlay to all of this is that China now has the greatest number of Internet users in the world, numbering 253 million with 84.6 per cent of them with broadband access. China has 39.5 per cent of the world’s Internet users. The United States has 214 million persons online.14 In late 2009, it was announced that domain names will in future be in a variety of languages. Thus will inevitably change the flavour of the Internet.

The success of the Internet can be measured in various ways. One is to recognise that there is an increasing problem for suitable Internet names to be found when they are all in English. Users are resorting to longer and longer names. In addition, bodies such as ICANN, which controls Internet protocols and domain names, are investigating new domain names such as .eco for ecological issues, .sport for sporting matters, etc. There is also strong interest in creating domain names for ethnic or cultural groups such as the Maoris from New Zealand or the Sami from Sweden. There could also be domain names for language groupings with Hindi, Putonghua or many other choices. This indicates that there is a sense that people see some form of identity through their domain names or Internet address. They also wish to be able to communicate within groupings as well as achieving the unexpected or that they ‘feel lucky’. In a relatively short space of time, say mere years, the Internet has grown from being a novel communication network for defence researchers to an incredible web for seemingly anything and everything. If we find the present Internet environment difficult to comprehend and predict, it is worth applying the imagination to the plethora of opportunities and impacts which an Internet with the vastly increased variety of domain names would have. The wide range of scenarios, with such a differently structured Internet, would most assuredly have a dramatic effect on the library and its services.

The Library at Alexandria in the first century AD was able to boast that it had collected all the manuscripts known to be in existence at that time. Now, no such claim could be possible. The rate of information being thrust at us is such that it not only makes it difficult to find reliable authentic information but also almost impossible to determine and absorb the correct information. While new scenarios can be constructed to cope with the volume of information on the Internet, new ways need to be established to address the authenticity, reliability or even the accuracy of this information.

Scenarios, as will be demonstrated in this book, are a way of imagining and articulating new, future ways of dealing with difficult issues. Peter Schwartz is famous as the author of The Art of the Long View and a leading advocate of scenario planning:

Scenarios are a tool for helping us to take a long view in a world of great uncertainty. The name comes from the theatrical term ‘scenario’ – the script for a film or play. Scenarios are stories about the way the world might turn out tomorrow, stories that can help us recognise and adapt to changing aspects of our present environment. They form a method for articulating the different pathways that might exist for you tomorrow, and finding your appropriate movements down each of those possible paths. Scenario planning is about making choices today with an understanding of how they might turn out.15

Scenarios have been used by business and the military to explore options and unpredictable circumstances which might develop for their businesses or in geopolitical environments. They prove especially valuable in enabling people to think about issues and options which they do not ordinarily allow themselves to think about. These techniques are now also being increasingly used in the information world. These scenarios can operate at simple or complex levels. As with our own lives, there are choices to be made daily. We have choices in how we travel to work each day and how we return home. Choices that we make can have inconvenient, stark or even tragic consequences. We all recognise circumstances where our futures might have been different if we had chosen to walk one day, instead of riding a bicycle or had been two minutes later arriving at a particular place. It is far better to choose a future, rather than having it chosen for you.

When we apply this logic at levels of increasing complexity, change becomes ever more important if we are to position our information entities to be able to deliver high-quality responses to expressed information need. Constructing scenarios can be as complicated as a game of chess in which each player, on each move, has an increasingly large range of options and permutations to consider. Scenarios seek to harness such complexities in order to form manageable options.

In dealing with the information world there can be any number of future scenarios. A number of possible scenarios are explored over the coming pages. The scenario can challenge our conventional thinking about situations which we might accept unquestioningly. The scenario which suggests that we return to past traditional publishing models will not be entirely successful in an Internet age. Many people now have access to the web and may instantly become authors. The circulation figures of countries are declining.

Newspapers in a number of developing countries are thriving. This is especially the case in China and India. As such, the print vehicle is performing very well financially. In China, most of the publishing industry, as revealed in official statistics, is concentrated around Shanghai and the Yangtze River Delta. This is not the case with print newspapers which are very strong in the far west of China and Xinjiang.16 Part of the reason for this is the large ethnic diversity of that province.

While newspapers in the United States are failing financially, they are also struggling to find a business model in the Internet environment. With this conflicting evidence different scenarios can emerge as to the possible futures for print and Internet-based newspapers.

The size of Internet populations has already been explored in earlier pages of this chapter. The largest Internet populations are now more in China and India than in the ‘West’. The Internet users in China number more than the total population of the United States. This is changing the flavour, character and direction of the Internet. The ethnic character of the web is also changing, with large populations of different ethnic groupings realising the capacity of the Internet. Disturbances in Xinjiang with the Uyghur and with the political opposition in Iran were heavily influenced and powered by electronic media.

In constructing scenarios for the future of newspapers, we can see that they are sharply impacted upon by factors such as emerging Internet populations and different ethnic groupings with their aspirations. That there are changes to domain name regulations to allow for languages other than English merely extends the viability and power of these potential scenarios.

Copyright is in the public domain. Plagiarists are found relatively easily on the Internet, as evidenced in recent cases involving a politician in Australia as also with a number of other countries, through the use of software tools such as Turnitin. A Chinese software version can now also be used to detect plagiarism. In academic circles plagiarism matters but it is not perhaps so important to the future world of blogs, wikis and other alternative sources of news and opinion. It has been suggested, in places such as The Economist, that copyright may deter creativity. Traditionally – and certainly in academic publishing circles – it is critically important to acknowledge the words of other authors. It is an academic ‘crime’ not to do so. The argument is often made that culture affects attitude and practice toward copyright. The reverence for the teacher (laucher) is very strong in Chinese culture. It is argued that the quoting of that teacher is a sign of reverence. How could a student express an idea better than the teacher’s words? So there are different attitudes and practices concerning copyright and the acknowledgement of attributed words in different parts of the world.

A scenario can emerge from this discussion that copyright as a legal concept could change, or could be applied in different ways in different cultures, in different circumstances. Copyright in the commercial would have a much stronger, harsher and punitive aspect to it. If an organisation holds copyright for a particular invention, product or artistic expression then they clearly wish to protect the revenues which may flow. Any loss of sales obviously impedes the economic viability of the organisation. As a result, working to extend the copyright protection of a product becomes very important to an organisation. The extension of the protection of copyright recently under law from ‘Lifetime plus 50 years’ to ‘Lifetime plus 70 years’ is often known as the ‘Donald Duck clause’. This is because Walt Disney’s Donald Duck character would have come out of copyright and thus been free for anyone to use if the copyright had not been extended. So expect more extension to the copyright protection clauses as Donald Duck gets older.

As discussed elsewhere, the Open Access movement aims to make materials much more available, and free if at all possible. The scenario which may emerge from these ideas concerns the justifiable length of copyright and the pressure to enable ideas to be freely available on the Internet. Various positions and possibilities can be determined in this area of copyright. As complex as it is, scenarios can and should be developed contrasting one position as opposed to another. These scenarios can then be run against other tensions such as the Internet, the growth of the Internet in different cultures, or the use of the Internet and copyright by different ethnic groupings.

Other scenarios may deal with the amount of education we need as to the sources of reliable information and/or which author blogs are professional and responsible. Dealing with the amount of information available on the Internet is formidable indeed. Dealing with the issue of accuracy or authenticity of the information available through those sites is another issue again. For example, a far right-wing organisation was recently found to have constructed a website to provide an alternative view on the life of Martin Luther King. The site was professional in appearance but totally misleading as to the information it contained. ‘This is a website produced by a white power organisation and is one of the best/worst examples of a site that is trying to pass itself off as something entirely different. Proceed with caution on this one.’17 The scenario being developed here relates to accuracy or inaccuracy of information. It may also relate to issues of censorship. The scenario can construct or apply to scenarios in any or all of the issues which we have discussed already in this chapter.

A tool to use in this act of scenario construction was made prominent by Clayton Christenson18 in The Innovator’s Dilemma that disruptive technologies fundamentally change our total technological interactions. According to this theory, a disruptive technology might be the PC, which totally replaced the mainframe and led to the ascendancy of the Microsoft Corporation and the power of the individual on the Internet; another might be the PDA (Personal Digital Assistant), which mostly replaced the paper diary; and now the mobile phone is absorbing the diary and a host of other functions to be a disruptive technology to the earlier two technologies. There will be more discussion of disruptive technologies and their impact in a later chapter. An extension of this thought is that disruptive innovations fundamentally change the rules by which marketplaces operate and are controlled. Evidence of this can be found in the United States Presidential election campaign by Barack Obama, which mustered unprecedented financial and moral support from individuals across the Internet. It has been noted widely in the press that the traditional fund-raising approach by Hillary Clinton in her political campaign among the power brokers and the ‘big money end of town’ worked but nonetheless failed to match the innovative approach of her opponent. Successfully predicting innovation or disruptive influences can enable organisations to achieve positions of future strength before the influence has firmly embedded its position.

A few possible scenarios have been offered here to explore possible futures caused by the impact of the Internet on communication, ideas, information and understanding. Other scenarios are clearly possible. The impact of thinking and preparing for changes with such possibilities lies in the basis of having sound and stimulating methodologies by which order can be created out of seeming chaos. It is also a way of recognising complexity and different, even divergent, paths to future positions.

That we talk of change as much as we do is a clear indication that many of us find it difficult to relate to or cope with change. Change can be unsettling. In the workplace, the less influence we have over what change occurs and how it occurs can lead to anxiety and resistance to change. Those who are less powerful in an organisation will inevitably suffer most in this regard. Lower-level staff have little control over their work flows and directions and can, in these circumstances, be very resistant to change which they did not foresee or that they do not understand or that they feel threatened by. President Obama in 2009 made a compelling and indeed convincing case for change in US society and its economy. In many senses this case was made so much easier because of the obvious and widespread observation by the US populace (and also the world, although they do not get the chance to vote in the United States) of the need to do something different.

This is not always the case for staff, clients and managers within library and information service environments as there is not always an obvious case for change. The need for change is perhaps more obvious with an aging workforce and where members of that workforce have been in their present roles for very long periods of time. When combining this reluctance to change with the increasing average age of staff, the task of re-shaping an organisation can be very difficult indeed. Engagement in the process of determining a new future is an ideal way to enable staff to participate in shaping the future direction of the organisation for which they work. The Scenario Planning process enables engagement, allows gradual understanding of the environment in which organisations find themselves, encourages choices between futures and enables shared ownership of the outcomes.

The Chief Executive of the popular MTV Networks, Judy McGrath, believes that ‘change has to be in everyone’s DNA, personally and professionally’.19 It seems that we are being subjected to unprecedented amounts of change, the only constant in our lives. We all feel that the rate at which the change is taking place is constant and swift. We can only notice this rate of change with hindsight but we need to bear this prospect in mind as we look forward. A senior career in libraries today will have spanned the time where 5 x 3 catalogue cards were produced in a handwritten form, to where they were produced in multiple copies (for added entries and so on) by vendors, through to the MARC record for online catalogues and now the metadata processes. This is a spectacular amount of change in the space of less than three decades. And yet, despite McGrath’s belief, change is not part of our DNA and the human spirit often longs for periods of stability.

It is important to recognise that there has been much change and also that it is beneficial to be able to measure that rate of change. In a narrower sense, each of us can see this rate of change through McLuhan’s rear vision mirror view of our own history. We only have to look at events in our past and then to recollect how much change has occurred since that event. By looking back to a particular development, one can often readily witness how short a time period has elapsed since that development. By taking one’s mind back to that time and remembering forward it can be seen how difficult it is to accurately predict or even understand the future from a point in one’s past. For instance, by looking backward to when microfiche catalogues came into existence, one can remember how liberating they were. The microfiche catalogue, in many senses, was the first library catalogue produced using the power of the computer to manipulate and organise data. It enabled many sets of the catalogue to be produced so that they could be located on all floors of the library, could be located in academic departments elsewhere on campus, and could be exchanged with other libraries for quick identification of held resources. It was revolutionary. Remembering back to the time it made its appearance in libraries in the late 1970s to early 1980s, it was difficult to imagine the exact future which we have today a mere three decades on. It was, however, clear, at least in trend terms, that the computer was going to drive the change, the potential for further enhancements. The computer had already enabled the production of multiple card catalogue sets for each title and now had produced the microfiche catalogue. But what would the form of the future catalogue be?

Another instance to think about is to ask oneself when you became aware that the Internet would be a vehicle to transport library content? Already in the 1980s major subject indexes such as Index Medicus and actual journal content were being produced on CDs. The number of CDs that were required for the rapidly increasing range of content meant that it soon became apparent that a ‘jukebox’ was needed to efficiently manage the large numbers of discs. Soon there would be a need for many ‘jukeboxes’. Then it became clear in the early 1990s that this journal content could be made available across the Internet. Now, a mere decade and a half later, the Internet has became so pervasive and perhaps intrusive to our lives. But remembering back to the first time when there was awareness of this potential is a moment of some excitement. Excitement in that this was indeed an even more radical development in the potential for the library to reach out beyond its walls and deliver content to where the user was physically located.

So the exercise of remembering back and then looking forward from that remembered time is a very useful exercise to help us understand rates of change. It also helps us understand that change will happen but that it is most likely to happen much sooner than we can project or predict. Change will wait for no person. This will be dealt with again later in the book.

Change of attitudes toward the future

In so far as it is possible, we need to shape our future, rather than letting the future happen to us. It is apparent that we have many possible futures open to us but the difficulty lies in identifying those futures and in choosing wisely amongst them. In more optimistic times people believe that resources inevitably follow to support growth. Today, there is a widespread pessimism, even fatalism, about the state of the world’s environment which, couched with the severe economic downturn, is making people blind to positive opportunities. It is once again worthwhile remembering the Chinese word Wei Ji meaning danger and opportunity. They go ‘hand-in-hand’. The scenario planning methodologies aim to assist and direct thinking in a constructive sense, even through emerging darker resource moods. In times of dark moods toward the future, the first thing that has to change is how we allow ourselves to think about the future. If we allow ourselves to begin to think about solutions, then the methodologies taught in this book will greatly open the possibilities and/or opportunities.

Development of scenarios as a discipline

For the future library to survive and prosper, the continuous alignment of its strategic direction with the demands of the environment is vital, especially when the speed of changes is rapid, and the scope extensive. However, changes that are unpredictable and complex in nature can sometimes be very threatening. In the face of uncertainty, psychological attachment to, and the defence of, what is destined to change can be dangerous. When library managers underestimate the impact of the emerging trends on their traditional roles and values, they are not positioning their library and themselves to capitalise on the changes emanating from these trends. On the other hand, if the threat of change is overestimated, yet one’s abilities to shape the future are underestimated, one might still be locked into inaction in decision-making.21 Coping patterns of ‘bolstering failing strategy, procrastination and buck-passing’ are identified as the typical signs of avoidance behaviours in responses to threatening change.22 As noted by Pierre Wack, inertia and failure to decide is often rooted in ‘the inability to see an emergent novel reality by being locked inside obsolete assumptions’.23

To free planners from obsolete assumptions, to overcome decision inertia and perceptual blind spots, a new planning tool called ‘Scenario Planning’ emerged in the 1960s. The US government initially applied it during the Cold War for geopolitical and military analysis. In the 1970s Royal Dutch Shell pioneered its use in the corporate sector and successfully prepared the company for the oil crisis in 1973.24 Since then, scenario planning has been widely applied in both public and private sectors for product innovation, organisational re-engineering, public policy analysis, city planning, crime prevention, and NGO services.25 Numerous articles in management journals have been published recording how creative decision makers embrace it as a tool to stimulate organisational learning,26 to change organisation culture,27 and to challenge deeply held beliefs.28 A consultancy firm registered TAIDA (Tracking, Analysing, Imaging, Deciding, Acting) as its trademark and the name of the framework is now used in ‘hundreds of scenario planning projects for public and private business and organisations’.29 By systematically identifying and analysing the relationship between the critical driving forces in the external and internal environment, leveraging the different perspectives of a wide spectrum of stakeholders and experts, and imagining different possibilities and corresponding strategies, managers are better prepared for action as the future unfolds.

In the late 1990s, the American Library Association published a handbook providing tips on writing the scenario plots for public libraries30 in utilising the scenario planning process. Information professionals in special libraries were also encouraged to apply scenario planning not only for internal library planning, but also to ‘help their leaders understand that they provide insight to the organisation and that they don’t just catalog and warehouse data’.31 Steven J. Bell contended that the scenario approach could be applied to achieve a sustainable development of academic libraries.32 In order to preserve its traditional core values, the library could take up new roles as a primary change agent. To achieve this, library managers are challenged to adopt scenario planning as a strategic and learning tool to visualise alternative futures that could be probable, possible, and, most importantly, a preferred future for them to construct. A matrix of scenarios, characterised as ‘failing’, ‘conventional’, ‘technocentrist’ and ‘transformational’, was drawn to illustrate different possibilities for the future library. Bell argued that ‘traditional strategic planning may now be too constrained to properly respond to crisis and opportunity’. This was echoed by Stuart Hannabus when he criticised strategic planning as being too focused on the present to be an effective planning tool for a turbulent future.33 The top-down, criterion-based approach and bureaucratic inflexibility inherent in traditional strategic planning does not help today’s librarian to identify contingent decisions for unexpected changes or paradigm shifts in the information explosion age. On the other hand, the scenario development process enables conventional mindsets, existing strategies and people’s competencies to be checked against various alternative scenarios. In a nutshell, the scenario approach enables managers ‘to focus on opportunity-seeking planning rather than operations-driven planning’.34

Putting theories into practice, the Library of the University of Technology, Sydney applied the scenario planning process to achieve a shared understanding about its future direction.35 The University of New South Wales Library, also in Sydney, employed the scenario modelling techniques for organisational restructuring, staff development, space planning and client services.36 In the United States, the structured and disciplined techniques in developing plausible scenarios were employed at the Libraries of the University of NebraskaLincoln, to develop four possible futures to answer the question: ‘How might the collection develop over the next five years?’37 In Denmark, different stakeholders participated in scenario workshops to engage in ‘strategic reflexive conversation’ on three public library development projects.38

Regardless of the size of the library or where it is placed within its parent organisation, scenario planning can provide the stimulus necessary to direct it toward an imaginative thoughtful and stimulating future.

1.Bernstein, P. (2009). Australian Financial Review, 4–5 July, p. 40

2.The Open Access Movement is effectively an extension of the Open Source movement whereby programmes sought to create software that could be modified by all and not be proprietary. In a similar way libraries have commenced the Open Access movement to make as much literature as possible available freely on the Internet and not locked in proprietary publisher databases.

3.Meyrowitz, J. (1985). No Sense of Place. New York: Oxford University Press.

4.Legacy collections can be described in terms of the print never to be digitised because of copyright restriction and an inability to find the copyright owner. It represents a significant corpus of material.

5.Chown, M. (2008). ‘Is science fiction dying?’ New Scientist, 12 November, pp. 6–49.

6.Ibid. p. 47.

7.Skidelsky, R. (2008). ‘No perfect knowledge out there in markets’. China Daily (HK Edition), 31 December, p. 9.

8.Available at: www2.ku.edu/~sfcenter/library.htm (accessed 20 July 2010)

10.Gibbs, N. (2008). ‘President-Elect Obama’. Time, 17 November, p. 25

11.Carr, N. (2008). The Big Switch: rewiring the world, from Edison to Google. NY: Norton, p. 228.

12.Markoff, J. (2008). ‘Internet Traffic begins to bypass the US’ NY Times.com, 31 August. Available at: www.nytimes.com/2008/08/30/business/30pipes.html?scp=1&sq=Internet%20traffic%20bypasses%20us&st = cse (accessed 31 August 2008).

13.Technorati (2009). State of the Blogosphere 2009, Available at: http://technorati.com/blogging/feature/state-of-the-blogosphere-2009 (accessed 12 May 2010).

14.Ibid.

15.Schwartz, P. (1991). The Art of the Long View. New York: Doubleday Currency, pp. 3–4.

16.O’Connor, S. (2009). ‘Beyond the Great Wall: Experiences with ETDs and open access in China and South East Asia’. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10397/ (accessed 12 June 2009).

17.See, for example, http://philb.com/fatesiks2.htm (accessed 6 July 2009).

18.Christenson, C. M. (1997). The Innovator’s Dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

19.‘Can Judy McGrath keep MTV Networks up with the beat of the Internet era?’ The Economist, 22 November 2008, p. 72.

21.Star, J. (2007). ‘Growth scenarios: tools to resolve leaders’ denial and paralysis.’ Strategy & Leadership 35(2): pp. 56–9

22.Wright, G., van der Heijden, K., George, B., Bradfield, R. and Cairns, G. (2008). ‘Scenario planning interventions in organisations: An analysis of the causes of success and failure.’ Futures 40(3): pp. 218–36

23.Wack, P. (1985). ‘Scenarios: shooting the rapids’, Harvard Business Review 63(6): 139–50.

24.Cornelius, P., Van de Putte, A. and Romani, M. (2005). ‘Three decades of scenario planning in Shell’. California Management Review 48(1): 92–109.

25.Weinstein, B. (2007). ‘Scenario planning: current state of the art.’ Manager Update 18 (3): 1.

26.Chermack, T. J. (2008). ‘Scenario planning: Human resource development’s strategic learning tool.’ Advances in Developing Human Resources 10(2): 129–46.

27.Korte, R. F. and Chermack, T. J. (2007). ‘Changing organisational culture with scenario planning.’ Futures 39(6): 645–56.

28.Bradfield, R., Wright, G., Burt, G., Cairns, G. and Van Der Heijden, K. (2005). ‘The origins and evolution of scenario techniques in long range business planning.’ Futures 37(8): 795–812

29.Lindgren, M. and Bandhold, H. (2005). Scenario Planning: The link between future and strategy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

30.Giesecke, J. (1998). Scenario Planning for Libraries. Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

31.Willmore, J. (2001). ‘Scenario planning: creating strategy for uncertain times.’ Information Outlook 5(9): 22–8.

32.. Bell, S. J. (1999). ‘Using the scenario approach for achieving sustainable development in academic libraries.’ Available at: www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlevents/bell99.pdf (accessed 8 April 2008).

33.Hannabuss, S. (2001). ‘Scenario planning for libraries.’ Library Management 22(4/5): 168–76.

34.Richards, L., O’Shea, J. and Connolly, M. (2004). ‘Managing the concept of strategic change within a higher education institution: the role of strategic and scenario planning techniques.’ Strategic Change 13(7): 345–59.

35.O’Connor, S., Blair, L. and McConchie, B. (1997). ‘Scenario planning for a library future.’ Australian Library Journal 46(2): 186–94

36.Wells, A. (2007). ‘A prototype twenty-first century university library.’ Library Management 28(8/9): 450–9.

37.Giesecke, J. (1999). ‘Scenario planning and collection development.’ Journal of Library Administration 28(1): 81–92.

38.Kristiansson, M. R. (2007). ‘Strategic reflexive conversation: a new theoretical-practice field within LIS.’ Information Research 12(4). Available at: http://informationr.net/ir/12-4/colis/colis18.html (accessed 23 April 2008).