Toward a new way of thinking

This chapter

The basic presumption or driver for this chapter is that many minds are needed to make good future decisions. It is important to think about how to achieve the involvement of as many people as possible in the future decisions for your organisation. It is difficult to achieve this involvement but it is more difficult to get people to think for themselves and to articulate those views. To gain real options and a diverse set of views, it is crucial to get views from all different perspectives and to allow for the different ways in which people think and perceive the world around them. This chapter is devoted to achieving the best involvement and the best articulation of views across the organisation and its user communities.

How to organise for decisions

Cass Sunstein1 has written widely about how we seek to make decisions through the processes of deliberation. In any group deliberation situation it is important to avoid ‘same thinking’ or ‘groupthink’. This is where ideas do not get tested in a genuine fashion because conformity to a certain way of thinking is deemed to be the appropriate way to present the findings. Because the group is understood to think in a particular fashion, ‘outside’ ideas are not easily allowed in. Irving Janis is acknowledged as suggesting that ‘groups may well promote unthinking uniformity and dangerous self-censorship, thus failing to combine information and enlarge the range of arguments’.2 The point of this scenario planning process is to extract from the members of the group the maximum value of the individual and collective insights. A failure to achieve a maximum understanding of the environment in which the library is and plans to be would be dangerous and would blunt the value of any planning processes. Sunstein highlights that the failure of the CIA to report correctly on the Weapons of Mass Destruction in Iraq was partly due to ‘groupthink’ and not being able to obtain and use information which its staff actually possessed. He also describes another investigation into the disaster of the Columbia space shuttle crash where similar stultifying processes occurred, again even though many of employees had the correct information and knowledge. Individually, they could not think or see anything different to what the group ‘allowed’ them to think. The group subconsciously had placed boundaries on what was allowable and what was not.

In any scenario planning process it is crucial that the information gathering allows time and periods of introspection. The information gathering should also be a group process. By working as a team, that group of persons can establish a rapport with each other and with the information gathered. By allowing time for the process the team has more time to get to know and understand each other and also to grow the inter-connectiveness of their observations. Information gathered in one quarter will make a connection with that from another quarter. Strange connections will begin to emerge and a group understanding of the various sources of relevant information will also potentially throw up ‘left-field’ information.

A good example of this is The Charleston Report: Business Insights into the Library World.3 This very short publication provides brief collections of information, data and insights from many sources. The insights resulting from this eclectic collection lead to further and unexpected views for the future of individual libraries. Another source is Access: Asia’s newspaper on electronic services and products.4 This small newspaper does have a connection to the iGroup, a large distributor of information services and products across Asia, but the editor, Clive Wing, manages to capture the current and topical issues in articles that are easy to read and digest. Research is so important to opening eyes to different points of view.

Another way of seeing the value of divergent views is to understand the work on intelligences by Howard Gardner. In distinguishing intelligence capabilities our perception of ‘brightness’ quickly changes. Gardner wrote and researched extensively on issues surrounding our understanding of intelligence, creativity and leadership. He trained in social and educational psychology. His studies pursued the breakthroughs by individuals which led to genuine change and creativity. The Theory of Multiple Intelligences was first published in 1983. In this work, he defines the seven types of intelligence capabilities as:

1. Linguistic: the sort shown, in the extreme, by poets. It is also the capability to write and express ideas. The ability to work in a multi-lingual environment.

2. Logical/Mathematical: not only displayed in logic and mathematics but in science and business generally. Society values those who can balance budgets and indeed make money.

3. Spatial: the ability to hold in your head a model of the organisation of the world around you. It is also the ability to work in a space in three dimensions. When we talk of the ‘library without walls’, perhaps we need a different spatial sense. Typically this could be the skills of an architect or an artist.

4. Musical: This is self-explanatory. It is another intelligence of balance and rhythm.

5. Bodily/Kinesthetic: the sort shown by, say, dancers or sports people; the use of the whole or parts of the body to fashion some product or performance.

6. Interpersonal: the awareness of how to get along with others. This is also the capability to ‘encourage’ others to work together and to work to an agenda. This is a key attribute of the leader. In a world where change is also a constant, this is a vital leadership intelligence.

7. Intrapersonal: self-knowledge. This enables us to move beyond self-doubt. It reflects knowledge or confidence to trust one’s own judgement or set of work or life experiences; rather than continuing to consult or avoid taking a decision.5

As the Australian Alistair Mant indicates in his book Intelligent Leadership: ‘The effect of [existing educational systems is] to over-educate and over-promote narrow people – those who are especially practised in (for example) the logical/mathematical and linguistic capabilities while neglecting the complementary capabilities of other potentially valuable people.’6 In our context here in this book we are seeking to recognise that we do not think ‘outside the box’ as often as we ought. Systems are created in which we comfortably reside and operate. It is only when we are set the task of moving differently that we struggle to think of different ways of doing what has been very familiar. If we were set the task of re-inventing the library, would we be able to do so? Mant draws on the work of Gardner to find a way of explaining how breakthroughs can occur in different fields of endeavour which can fundamentally change the way in which the activity or the field are perceived or how they operate. Equally, we can view the intelligences or perspectives which many people can offer on future directions for a library. He, like Gardner, draws from the lives of people he has researched the approaches to their life’s work which illustrate the strengths of different types of intelligence. It is reassuring that the most successful people in terms of leadership or changing perceptions of industries do not have a standard set of qualifications. They often think differently; they see things which others can only imagine. Albert Einstein once said: ‘I am enough of an artist to draw freely on my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.’7 So different perspectives and ‘heretical’ thinking will introduce new concepts, ideas and perspectives into a group.

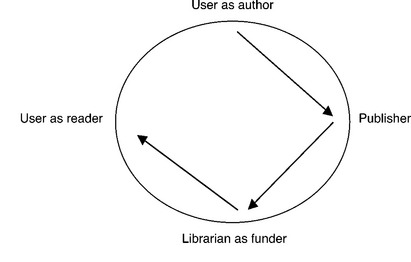

As Mant says: ‘Judgement is what you do when you don’t (and can’t) know what to do.’8 The true essence of leadership is to change and shift systems. Leadership in this sense is to see the world differently and to be able to influence others to work with the leader to adopt the change into normal operations. To do this is to recognise how the future library model should be shaped to meet the information need of its community. There is a need to fundamentally understand the business models which libraries currently operate in. The business model defines the range of services the library intends to present to a clientele whose needs they understand. It also defines the way in which libraries operate with each other and the publishing or, more broadly, the information industry. An apposite example of this is the traditional business model which publishers have had in the subscription model. Here the financial costs of publishing have been borne by subscriptions through libraries. The more subscriptions the greater the revenue the greater the profit. Essentially the business model is to enable the communication of peer-reviewed information from the author to the reader. The publisher provides the means while the library provides the funds.9 So leadership and thinking differently have much in common.

Is it all straightforward?

The principal reason for any scenario planning is to best position the library for the future. The future should be one at least three to five years hence. We have already seen in earlier chapters that the rate of societal and technological change is vast indeed. The Rear Vision Mirror exercise has demonstrated how fast change is. It is only in this timeframe that we can expect to gain the best positioning. It is only in this timeframe that we can expect to give effect to the changes which come out of this process. But it must be recognised that there will be change through this process. Much can and will be achieved in this timeframe. Change is the only constant! It is difficult for staff at all levels in the organisation to deal with the change which will come through the ideas and directions which arise and are agreed to as the Preferred Scenario. It is untrue to say that the change will affect those at the lower end of the library hierarchy more than at the upper levels. The extent of the impact will depend on the attitude of individuals, the length of service in particular positions, their career position and their career or life aspirations. So the management of change will be a major component of the scenario planning process as well as its outcomes. Achieving engagement in the planning is so important for the implementation phase. So at this stage of working through to new scenarios it is very useful to understand the classic positions which organisations go through in dealing with where they are now and where they might wish to be.

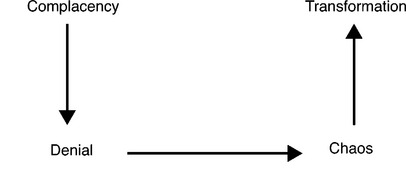

The classic organisation steps through which an organisation goes consist of these four phases as it come to grips with change.

Each of these steps requires understanding and planning to deal with detachment of staff and to allow them as full a participation as possible. Typically, organisations have many of their staff in employment for long periods of time. Many of these organisations have the average age of their staffs to be close on 60 years of age and the prospect of change is not very inviting. ‘After all it has worked very well up until this, thank you very much.’ Many staff have also been in their existing positions for many years and are either very happy and content where they are or may be actually looking for more stimulation and scope to act. Still, the organisation often looks the same as it has for many years. This is one piece of evidence that the organisation is complacent. Another may be the extent to which the organisation moves outside its own walls, often and candidly, into its user and governing communities to listen to what is being said. Having begun the process of scenario planning, staff in the organisation could be seen to be in a state of denial. Denial might describe that they do not believe that anything has to change; ‘It will all move easily and nicely without too much interference.’ It is highly desirable to engage all the library staff in the planning and contribution phases so that their ideas, positive or negative, can come to the fore and be included in the information-gathering and research phases.

What happens typically to any organisation which has moved through these first two phases is that there is what could be described as chaos. This is a state where the familiar structures are being threatened or potentially changed, sometimes significantly. The place which individuals had for themselves in their work world has been challenged. The desk is no longer the area of familiarity and security. Procrastination can take many forms in this circumstance. Research indicates that people can be unrealistically optimistic about their capacity to undertake change.10 The further ahead the change, the more procrastination occurs. If the present is not so uncomfortable as to force change then it will be postponed. Getting engagement rather than resistance is the most critical issue in selecting different futures for the organisation. It is easier to sit out the process and snipe on the side. This option is to be avoided.

It is worth noting, given that change is inevitable and actually happening, that staff who have been in positions for a long period of time will strongly opt for different positions with differing responsibilities in this phase of change. This is especially if they have been engaged with the process from Day One. Staff involvement might not have been intensive but if they have been able to hear of the reasons for this new planning, they may have actually become interested in what might happen. The exclusion of staff at any level across the organisation can only create disharmony and conflict at this penultimate stage of the change process. Not all staff will benefit from involvement; not all staff will want to be involved other than tangentially; the levels of participation and knowledge can always be achieved across the organisation to allow for these different levels of interest. The final phase is obviously that of transformation. This is not reached easily or quickly. It may not be realised for a longish period of time. The organisation which has a Preferred Scenario to pursue will start to smoothly create the transformed organisation. We might all have differing ideas of when the transformed organisation is actually achieved. In a later chapter, there will be a discussion regarding the management of the ‘end game’. From another perspective, if plans are being put in place and executed toward that Preferred Scenario, then, it could be argued, the transformation has already occurred. Transformation is how the organisation views itself; the energy it has and the sense of purpose and drive.

So it is wise to be aware, to be prepared for the different phases of change which will occur. The preparation will be all the stronger and effective for a wide, if not total, involvement of the staff and clientele from the beginning and through the whole process. Politically, the more ownership there is by staff and the clientele, including the users and governance, the stronger the longer-term commitment there will be toward the achievement of the Preferred Scenario.

Confronting sameness

In constructing scenarios it is important to construct genuinely different and perhaps radically different models. It is important to have the mind free if real openness or creativity is to occur. This is not easy. The commonly quoted opinion of Thomas Edison – ‘Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration’11 – is entirely apposite. As Gardner analyses our intelligences above: intelligence comes in all forms; so it is that good ideas come in all shapes and sizes. It is a matter of allowing them through the filters of group thinking; of allowing different perspectives to emerge and to be heard. One perspective on this issue is that the best ideas are not new ideas but rather new perspectives or combinations of ideas. Andrew Haragdon relates the story of Thomas Edison’s invention of the light bulb.12 Edison’s first application for a patent was rejected because his invention infringed the patent rights of another inventor. ‘Edison’s contribution was not inventing electric light, but in combining it with improvements in generators, wiring, materials and business models.’13 So it could be with libraries. It is mostly defined that libraries are in the business of collecting, storing and disseminating information as books and journals.

Another perspective might be that libraries are really in the business of publishing but have increasingly outsourced that activity to commercial publishers. Looking at the expenditure levels of libraries across the world to publishers, it is an extraordinary amount of money each year. It would be measured in the hundreds of billions of dollars. It was true to note that superannuation funds flock to investments in publishing companies because of the high amounts of cash flowing through their accounts, the very low rates of bad debt and the consistent growth year upon year. The Open Access debate discussed in Chapter 2 is a good example of a new approach to an old problem. This is where the desire to have research available and peer reviewed is achieved via a different business model. But even within this ‘new solution’ there are many different models: where the library pays for the publication, where the author pays or where publicly funded research is subsidised for wide and free dissemination. There are many solutions buried in each solution. But many existing solutions are tomorrow’s burdens. This is especially the case when an idea can be so entrenched in the industry that an alternative is almost impossible to think of. In this situation the ‘same thinking’ approach blinds the whole industry to new or alternative solutions. The presence of different stakeholders in the planning session changes the dynamic and enables more open thinking. Unless there is open thinking, disruptive technologies can so easily and readily slip beneath the radar and not even be considered. This has been discussed in Chapter 2. The invention of the Personal Computer slipped beneath the collective thinking of large mainframe computer companies who had their futures firmly fixed on mainframe computing. They were so firmly fixed in their thinking that they could not begin to entertain how a small, underpowered but mobile personal computer could possibly replace their business model. But it did.

The MARC record has been essential to modern library operations. It has been used to provide order to library records, allowing libraries globally to exchange information about particular materials or published items.14 The MARC record came into existence only with the emergence of the computer as a means to store descriptive data for library materials and to be able to share that data. A consequence of this development was that the humble MARC record was a ‘disruptive technology’ to the highly reputable profession of cataloguing. Cataloguing was previously seen to be the core skill of the profession. It was seen as the basis for the future of the library. It was the core subject which every student of librarianship had to study … and pass. Now, the modern cataloguing department either does not exist or is a vastly scaled down version of its predecessor. The disruptive technology to the MARC record could now be seen to be free text search or what might be more universally called the ‘Google search’. Yet are libraries and their record structures ready for this development? Already Google Book and Google Scholar can retrieve virtually any book which exists somewhere in a library. But, as a profession, we work earnestly to maintain the MARC structure and only reluctantly allow the user to search the way they wish to.

One of the identified issues which can lead to a ‘blindness’ to strategically important issues is the size of the organisation. The larger the organisation the more difficult it is to get the different streams of the organisation to talk or to reflect on the performance and potential of other streams to that organisation. Yet it is crucial that these ideas or commitment to one viewpoint in an organisation interact with the viewpoints elsewhere in that organisation in a healthy and constructive manner. Nothing is sacred if scenario planning is to be effective! This is clearly not to say that all existing structures, tools or services are redundant or ineffective. It does, however, mean that they all should be tested using the various tools and exercises which this book has explored.

Research as a group

As part of the process of constructing the scenarios it is important to gather as much information as possible about the library, its performance, its usage, its reception in the communities which it serves and in the professional networks in which it operates. It is also important to gather demographic data about the state of publishing for the types of materials collected by the library, the publishing rates of books and journal titles, their costs over a period of years, the financial support given by the institution, and the numbers of staff and their levels of employment. It is important to document trends in all these areas. To benchmark one’s own library with peers, locally and nationally and even internationally, is then feasible. Another research group should be surveying the literature to pick up on the major trends affecting one’s own library sector and libraries generally. In this, some of the best insight will be found outside of the library literature. The assignment of the group appointed to gather information for the scenario planning process is to present their findings as trend data and with other insights into the library’s present and future positions. Data should be presented in as simplified a manner as feasible. Graphical representation of the data is often useful for better understanding. If the environmental understanding is presented in different sections, it would be useful to have a half a dozen bullet-point observations at the end of each section and an overall Executive Summary of the more important observations, again in bullet points. Being concise, thinking in big pictures and being honest in the representation of the data is to be effective. One’s own interpretation of the data should not be strongly represented at this stage of the process. An honest portrayal of the overall picture from as many aspects as possible will guarantee more committed involvement by all participants in the process later.

Collecting information about the environment in which your organisation is operating is critical, but it is crucial that it be open and wide-ranging. Reading Schwartz on this topic is instructive. He spends a whole chapter on this: ‘Information-hunting and gathering’. He describes the process:

The scenario process thus involves research – skilled hunting and gathering of information. This is practiced both narrowly – to pursue facts needed for a specific scenario – and broadly – to educate yourself, so that you will be able to pose more significant questions. Investigation is not just a useful tool for gathering facts. It hones your ability to perceive. Even your specific purpose in any particular research project is tagged to your inbred assumptions. You seed out those facts and perceptions which challenge those assumptions. You look for disconfirming evidence.15

In gathering your research and evidence remember to be honest and open in what is found and reported. The excellent book by David Hawkins on project strategy based on the classic Chinese book The Art of War reveals the importance of risk:

The biggest risk for most business ventures, however, is to adopt a risk-averse culture, which will stifle valuable opportunities and create a major risk of rigidity. Even worse, this approach will stop innovation and the lateral thinking attitude that is necessary to build or try alternative ideas.16

This is the time in the process to ensure that everything is open, that all possibilities are possible.

1.Sunstein, C. (2006). Infotopia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 11.

2.Ibid., p. 12.

3.The Charleston Report: Business insights into the library world. Published bi-monthly by the Charleston Company. ISSN 1091-1863.

4.Available at: www.aardvarknet.info/access/number44/monthnews.cfm?monthnews=01 (accessed 20 July 2010).

5.Mant, A. (1999). Intelligent Leadership. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, p. 41.

6.Ibid., p. 40.

7.O’Connor, S. (2006). ‘The heretical library manager: The library manager for the future’ Library Management 27(1/2): 62–71.

8.Mant, op. cit., p. 48.

9.O’Connor, op. cit.

10.The Economist, 2 January 2010, p. 55.

11.Available at: www.bartleby.com/59/23/edisonthomas.html (accessed on 12 April, 2009).

12.Hargadon, A. (2008). ‘Creativity that works’, in Jing Zhou and Christina Shalley (eds), Handbook of Organizational Creativity. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, p. 324.

13.Ibid.

14.The collapse of UKMARC and AUSMARC into one MARC record format highlighted the need to achieve better economics. This reality will also confront CHINA MARC which at this stage is incompatible with the MARC records. The gradual disappearance of the national MARC format highlights not only the economic but also the global nature of the information or library business.

15.Schwartz, P. (1991). The Art of The Long View. New York: Doubleday Currency, p. 64.

16.Hawkins, D. E. and Rajagopal, S. (2008). Sun Tzu and the Project Battle Ground. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 53.