Discovering the Difference

KEY IDEAS

→ Religious differences are best discussed as early as possible in the relationship.

→ Common ground, including shared values (see Shared Values Quiz), should be emphasized.

→ Personal respect—independent of respect for ideas or beliefs—must be nonnegotiable.

→ Each partner should express his or her own comfort with the difference.

→ Partners should keep communications open and invite questions.

After years of friendship, my wife and I began dating in December 1989. Within months—okay, within minutes—I knew I would eventually propose. I was 27, she was 24.

The usual series of misfit relationships in my early 20s had helped me figure out just what I wanted in the person I would marry, and she was it. Compared to everything else she brought to the relationship, the fact that she was a Christian and I was not was a footnote. Honestly, if I’d learned she had a second head growing out of the back of her neck, I’d have bought it a little hat.

We’d been friends since she was a freshman and I was a senior at UC Berkeley, but my atheism had never come up. Six months into our dating, it still hadn’t. I knew the subject had to be broached before I proposed. I’d been sitting next to her in church every Sunday, so there was no reason for her to assume I wasn’t a Christian believer as well. But I knew I couldn’t enter an engagement, much less a marriage, on false pretenses.

I was terrified of the possibility I’d lose her over it, but I knew it was just too big to come up years later as an “oh-by-the-way, funny-thing-aboutme” revelation. If it was going to be a big deal, it needed to be a big deal right then, before we got engaged, before we got married.

I figured a fast-moving car was the right place to bring it up.

We both lived in L.A. at the time and occasionally drove to San Francisco to see her parents. On one such trip, in the middle of the Central Valley, I mustered the nerve. I don’t remember the exact words I said, but at some point it was out there: I don’t believe in God, it’s something I’ve thought about seriously for years, and it’s not likely to ever change. Is that, uh … okay with you?

The tires thrummed for a while. She clearly hadn’t seen it coming and seemed a little shaken.

Finally she said, “Well … is it okay with you that I do believe?”

I said yes, of course. I’d known that from the beginning.

Another long pause.

“It has to be okay for me to go to church.” This was not in the form of a question. I said it was okay, of course it was. And then I learned something I might never have known otherwise: I learned why it was so important for her to go to church. As is often the case, it had almost nothing to do with theology.

She laid out the whole story. Her stepdad, a former Baptist minister, had an ugly falling-out with his church when he left his first wife for his second. As a result, he cut all ties with the church—not just that church, but all churches, all religion—and didn’t allow Becca’s very religious mom or her daughters to attend. Becca vowed to herself at the time that she was bloody well going to church once she got out of that house, and that no one was ever going to keep her from it again.

It wasn’t religious uniformity she needed from her eventual husband. She just needed to know that that particular bit of family history wasn’t going to repeat itself. It was never about salvation for her. As much as anything, her churchgoing was an act of proxy redemption for her mom.

That was an important discovery for me. I would have been troubled to learn that Becca’s religious beliefs and practices were centered on the fear of hell or even a need to please God. These are beliefs that I find not just false but dehumanizing. I don’t mind if my neighbor holds those opinions. As long as he doesn’t force them on others, I agree with Thomas Jefferson—it “neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” But if the beliefs of my intended lifelong companion fell into that fearful or obeisant category, I knew it would raise compatibility questions from my side of the equation.

Instead, I learned that she attended church for other reasons. In addition to family history, she went for the sense of community and human connection she felt, for the opportunity to slow down and reflect, to engage the world in a different way from the rest of the week. It was rewarding and fulfilling to her for reasons I could completely respect, even if I didn’t feel those needs as much myself. And her reasons were similar to the reasons most churchgoers go to church—to feel connected, to focus on meaning and purpose, to reinforce her own identity. God was the frame in which her human values were expressed, including values I shared with her.

I also learned that although she was Baptist by birth, upbringing, and baptism, she didn’t hold to several specific tenets of the Southern Baptist Conference that would have presented problems for me.1 One doctrine would have been a particular issue if she believed it: that those who do not accept Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior are consigned to hell. Even though I don’t believe in any such thing, I was glad to hear she didn’t either. A relationship in which one partner thinks the other is headed for eternal punishment after death, or is even worthy of such a thing, isn’t a healthy one.

Instead, by showing a tendency toward universalism—that all people are saved, regardless of beliefs—Becca was again very much in the U.S. Christian mainstream. Of U.S. Christians, 65% believe that non-Christians can end up in heaven, and the majority of those include the nonreligious among the saved.2 Good stuff.

By the end of the conversation, I was relieved, we knew each other a lot better, she had articulated her own values and beliefs in a way that was new even to her, and the biggest secret I had was out in the open.

And it had gone just fine.

Not that it always does. I’ll never forget the thirtyish man who came up to me after a talk in North Carolina several years ago, looking like he hadn’t slept in days—because, as it turned out, he hadn’t. He and his wife of 10 years had both been Mormon, but his religious faith had been slipping for some time. When he told her a week earlier that he no longer believed in God, she said he was “sick and evil,” then took the kids and left him the same night. He hadn’t heard from her since and didn’t know where his children were. Neither side of the family would answer his calls. An intense shunning wall had come down around him.

The nonreligious partner doesn’t always react well, either. I’ve heard from many who wondered if they could continue to respect their partners when they learned they were religious. “I have to admit that I suddenly saw him differently,” said one. “Instead of the confident guy I thought he was, I couldn’t help seeing a gullible, fearful child.”

In both cases, the partner hearing the news immediately conjured an extreme version of the other position and (naturally) recoiled in horror from it. It’s a perfectly human reaction. When we don’t have all the information, we fill in the gaps with the worst things possible. Remember what was written in unexplored regions around the edges of early maps? They didn’t just write, “Unknown.” They wrote, “Here be dragons.”

We often do the same thing with unknown human traits. As a defensive measure, we assume the worst. So a religious person often hears someone is an atheist and pictures Stalin. An atheist hears someone is religious and pictures Pat Robertson. Here be dragons.

Sometimes the shoe fits. But much more often, as we saw in Chapters 2 and 3, two people who think they are peering across an abyss will actually share most of their values, even if they’ve placed those values in different frames. So the revelation that a partner or prospective partner has a different worldview is not the end of the conversation; it’s the beginning. If we use it as a litmus test, a lot of wonderful relationships, including mine, would end before they began.

The revelation that a partner or prospective partner has a different worldview is not the end of the conversation; it’s the beginning.

That conversation needs to happen sooner rather than later. If there’s one thing experts on marriage agree on, it’s the importance of entering into the relationship with all cards on the table. If there’s going to be an issue, it needs to happen up front, before rings and vows and a shared mortgage—not to mention shared children—complicate things.

So … How Does It Usually Go?

The McGowan-Sikes survey asked several questions related to the first time couples learned about the difference in their beliefs. About 18% already knew about the difference before they dated, nearly half (47%) while dating, and 3% during their engagement. So altogether, the difference was out there before the wedding for about two-thirds of the couples.

Another 29% didn’t discover (or reveal) the difference in beliefs until after they were married. In some cases that’s because their beliefs were the same at the time they were married, and then one changed. In others, the difference was already there, but one partner—almost always the nonbeliever—didn’t reveal it until later in the marriage.

This is one of the key factors in determining how smoothly things go for these couples. According to the survey, those who enter the marriage with the difference already known have much lower levels of tension and conflict later on than couples in which one partner changed beliefs after marriage. A little more than one in five (22%) were both religious when they got married, and then one became nonreligious.

The least common scenario of all was the converse: Just 1% of couples were both nonreligious at the start, and then one partner became religious. And another 1% are currently “closeted” in their own marriages, meaning even their partner does not know they differ in beliefs.3

| Mixed at marriage | 67% |

| Both religious, one becoming nonreligious later | 22% |

| Both nonreligious, one becoming religious later | 1% |

| One partner still “closeted” to other partner | 1% |

So how does the conversation tend to go, the one in which a couple discovers their difference in beliefs? Just over a third of those surveyed (34%) said they were indifferent to the news. About 12% said they were intrigued or interested, 3% were excited or happy, and 1% couldn’t recall how they felt.

That leaves about half of all respondents expressing negative emotions—feeling worried, sad, disappointed, fearful, angry, confused, or betrayed. Religious partners were more than three times as likely to have negative reactions as nonreligious partners. A lot of this also depends on the “late change” dynamic that I mentioned. When a couple shares a belief system at the time of their marriage, then one partner changes beliefs, it’s common for the changing partner to feel guilt, while the other feels shock, grief, or even betrayal. (See examples in Chapters 7 and 11.)

It’s not always as simple as a single moment of change. Matthew, who was originally Baptist, lost his faith while dating Stephanie, a Christian. He eventually “rebounded” back to his faith, as he puts it, and they were engaged and then married. But shortly thereafter, he lost his faith again and now considers himself an atheist. “I feel like I’ve let her down,” he says, a common sentiment when a change in belief happens after marriage.

Sometimes a late change in belief results in complications beyond the couple, and the stories can be heartbreaking. “My husband gave up his life as a respected Lutheran seminarian, missionary, and missions coordinator because of my loss of faith,” says Christina, an agnostic in Minnesota. “Eight years of school and a life he loved. I don’t doubt him now when he says he made the right choice, that he doesn’t regret it or resent me for it, but at times I am concerned that someday he will regret his choosing me over his future in ministry.”

But just as often there are expressions of support or encouragement. “We were both agnostic when we married, but he followed his bliss and now considers himself religious,” says Jamie of Steven, her husband of 11 years. “I’m fine with that. He’s still the guy I fell in love with.”

“I made the terrible mistake of not telling her.”

My wife, Claire, has never been the hyperreligious kind that thanks Jesus for every parking space, but I knew her Catholic beliefs were important to her from the beginning. Even though I was an atheist by that time, I was raised Catholic, so it wasn’t unfamiliar to me.

I made the terrible mistake of not telling her about my disbelief until after we were married. Our relationship grew stronger over time, which made telling her even harder. I was attending church with her weekly, crossing myself, taking communion. I stupidly took the easier road of going through the motions to avoid confrontation.

But after three years of marriage, it became too emotionally draining for me. I decided I couldn’t be dishonest with her anymore. I was so nervous. Our lives were so good and happy, and I knew that this would put a big wrench in things. I’m nonconfrontational by nature, so I wasn’t even able to tell her face-to-face. I wrote her a letter and left it on the couch.

Her world turned upside down. The man she thought she had shared her faith with did not. There were questions of whether she would be able to stay with me, and many tears.

After hours of conversation filled with pain and frustration, we both realized that we absolutely wanted to stay together. Sure, the marriage wasn’t exactly what she had envisioned, but the rest of me was still worth it. I agreed that I would keep an open mind and never close the door on God if he were to try to “change my heart.” She agreed to be more accepting of my lack of belief even if I remained an atheist for good.

Life slowly returned to normal. I still attend church with her, but no more communion or crossing myself. She still hopes that I’ll “come to my senses,” but I think she is getting used to it.

If I could do it over again, I would have told her much earlier while we were still dating and the stakes were much lower. Then again, that might have ended our relationship, and she never would’ve married the wonderful heathen that she is still in love with today.

—T.J. (atheist)

See Scott and Dhanya, Chapter 6

As always, the specific identity and intensity of the partners makes all the difference. Scott prefers the terms agnostic and nonreligious for himself, saying, “I don’t practice religion and I don’t reject religion.” His wife Dhanya’s Hinduism makes for a more relaxed fit with a nonreligious partner than many other religious identities.

“Honestly, when Scott told me he was agnostic, I had no idea what that meant,” she recalls. “I don’t think I had heard that word before. I asked him what it meant and realized I was not even aware that there was a word that described this kind of thought process. It was pretty cool.”

“Like most Hindus, Dhanya doesn’t impress her beliefs on others,” Scott says. “From my experience, Hinduism is a very flexible and very personal set of religious beliefs and rituals. Hindus usually pick up their customs from their family, as opposed to the more collective church-oriented customs of Christianity.”

Dhanya’s customs include eating vegetarian food on Mondays and Thursdays and no beef or pork at any time, and praying every morning. Her prayer involves lighting incense and a candle and singing a few Sanskrit hymns. “It’s very much a ritual and not a prayer as in asking a god for something,” Scott says. “At certain times of the year, she is vegetarian for longer periods and does different sorts of prayers. When somebody is born or dies, there are other rituals to be done following the occasion.”

Confirming Shared Values

Suddenly learning that your partner has a different religious perspective can be disorienting. When religious believers learn that someone is not religious, some assume that their values—including empathy, compassion, even basic morality—fall away as well. A nonbeliever who learns that someone is religious often assumes that intellectual values such as critical thinking and skepticism are suddenly missing.

A study in Journal of Personality found that religious similarity is consistently less important to marital satisfaction than values similarity.4

But if they allow themselves to discover the difference before bolting in opposite directions, couples are much more likely to find that they agree on the relative importance of basic values.

The following quiz is designed to help couples assess the level of alignment in their values (opinions about what is good or important) regardless of their different beliefs (opinions about what is true or exists).

I think what keeps our marriage together after 43 years is what drew us together originally—compassion. We still share a concern for the welfare of all people, especially those who are abused or whose basic needs are not met.

— Joe, a secular humanist married to Ellen, a Protestant Evangelical

He has the same core beliefs that I have. Be kind to others, share, and show compassion. I just need the religion aspect and he does not.

—Lena, an Episcopalian married to Sean, an agnostic Baha’i

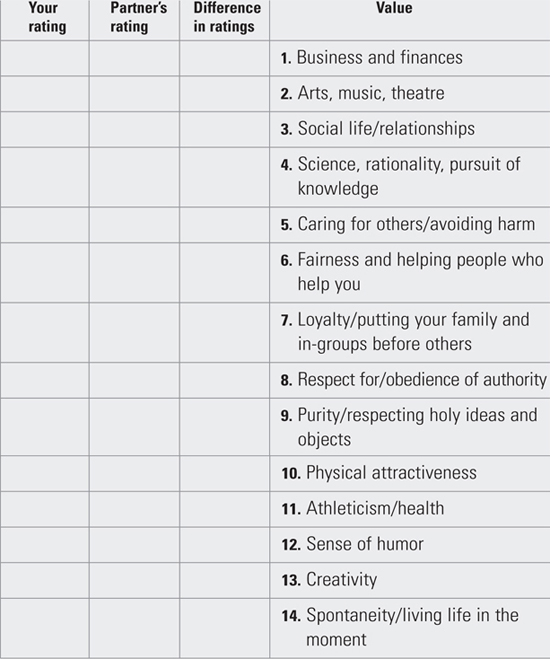

The Shared Values Quiz5

The Shared Values Quiz helps partners identify their most important values and areas of potential conflict. Values are one of many predictors of relationship success, so a high difference score does not guarantee future tension or breakup, nor does a low difference score guarantee a conflict-free relationship. It is meant as a tool for partners to communicate about what is important to each of them and identify areas of potential conflict.

Rate each of the following values on its importance to you, personally, according to the scale provided. Ask your partner to (separately) do the same. After you’ve completed the ratings, compare results. To calculate an index of difference in important values, subtract your partner’s rating from yours for each value. If you get a negative number, simply ignore the negative and make it positive (i.e., take the absolute value of the difference between your scores). Then total your differences.

3 = Extremely important

2 = Important

1 = Slightly important

0 = Not at all important

Total difference in ratings: ______________

Difference scores can range from 0 to 42. Larger numbers indicate greater discrepancies between your values and your partner’s. If you and your partner do not share the same values, you are likely to have very different goals and priorities, which can lead to conflict and relationship problems over time. Shared values are one sign of relationship health and success. Research has shown that the act of thinking about shared values can make people feel loved and cared for.6 Taking a moment to focus on the values you do share can be a good way to build a relationship or mitigate conflict.

Difference score 0–14: You and your partner have remarkably similar values. If you ranked these values from least to most important, the order may differ somewhat, but you most likely have the same top three values. It’s likely that even if your beliefs are different, you agree on quite a bit about what’s important to you. It probably comes as no surprise to you, but it’s likely that your shared values make your relationship stronger and more likely to go the distance.7

Difference score 15–30: You and your partner tend to agree on the importance of various values, but you may disagree about which values are the most important, or might be diametrically opposed on a small number of values. As a follow-up activity, rank the values from least to most important. This might help you identify aspects of your relationship in which you are more likely to come into conflict. Having insight into what motivates each other will aid in perspective taking during disagreements and give you a common language.8

Difference score 31–42: You and your partner have significant disagreement about what values are important. This can be a source of tension and conflict in your relationship.9 Maybe you said to one another, “You need to get your priorities straight!” Having very different priorities can be a challenge. As a next step, it may be helpful for each of you to rank the 14 values from least to most important. Identify the values that you both rank relatively highly as opportunities for shared activities and a place to build from. Remember that shared values are an important sign of relationship health, but that different values are not necessarily a death knell. Communication and relationship skills will be helpful while you negotiate and discuss your values (see Chapter 11).

(Many thanks to social psychologist Dr. Brittany Shoots-Reinhard of the Ohio State University for designing the Shared Values Quiz.)

The Bottom Line

A major difference in religious beliefs needs to come out as early and as straightforwardly as possible—definitely before marriage (if the difference exists at that point), and definitely before kids. Couples who use the opportunity to reinforce common ground and to start negotiating actual practices tend to do fine—if the difference existed from the start.

Couples who shared a worldview until one partner changed often have a more difficult road. Other weaknesses in the relationship often surface. But strengths surface as well, including some that may not have been identified before. The key is to recognize and articulate that the love, respect, and common ground values that formed the foundation of the marriage are still present, even though the framework has changed for one partner.