Information risk planning involves a number of progressive steps: identifying potential risks to information, weighing those risks, creating strategic plans to mitigate the risks, and developing those plans into specific policies. Then it moves to developing metrics to measure compliance levels and identifying those who are accountable for executing the new risk mitigating processes. These processes must be audited and tested periodically not only to ensure compliance, but also to fine tune and improve the processes.

Depending on the jurisdiction, information is required by specific laws and regulations to be retained for specified periods, and to be produced in specified situations. To determine which laws and regulations apply to your organization's information, research into the legal and regulatory requirements for information in the jurisdictions in which your organization operates must be conducted.

Step 1: Survey and Determine Legal and Regulatory Applicability and Requirements

There are federal, provincial, state, and even municipal laws and regulations that may apply to the retention of information (data, documents, and records). Organizations operating in multiple jurisdictions must maintain compliance with laws and regulations that may cross national, state, or provincial boundaries. Legally required privacy requirements and retention periods must be researched for each jurisdiction (e.g. county, state, country) in which the business operates, so that it complies with all applicable laws.

IG, compliance, and records managers must conduct their own legislative research to apprise themselves of mandatory information retention requirements, as well as privacy considerations and requirements, especially in regard to personally identifiable information (PII). This information must be analyzed and structured and presented to legal staff for discussion. Then further legal and regulatory research must be conducted, and firm legal opinions must be rendered by legal counsel regarding information retention, privacy, and security requirements in accordance with laws and regulations. This is an absolute requirement. In order to arrive at a consensus on records that have legal value to the organization and to construct an appropriate retention schedule, your legal staff or outside legal counsel should explain the legal hold process, provide opinions and interpretations of law that apply to your organization, and explain the value of formal records.

In identifying information requirements and risks, legal requirements trump all others.

Legal requirements trump all others. The retention period for a particular type of document or PII data or records series must meet minimum retention, privacy, and security requirements as mandated by law. Business needs and other considerations are secondary. So, legal research is required before determining and implementing retention periods, privacy policies, and security measures.

In order to locate the regulations and citations relating to retention of records, there are two basic approaches. The first approach is to use a records retention citation service, which publishes in electronic form all of the retention-related citations. These services usually are purchased on a subscription basis, as the citations are updated on an annual or more frequent basis as legislation and regulations change.

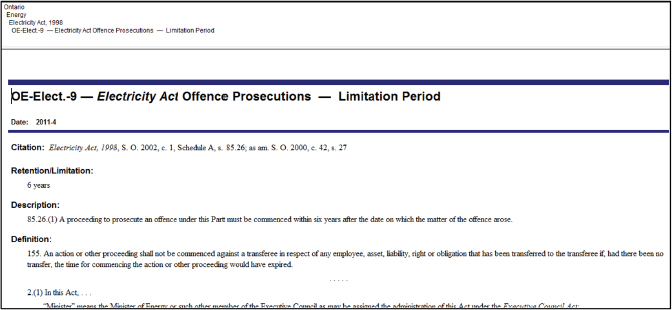

Figure 4.1 is an excerpt from a Canadian records retention database product called FILELAW®.1 In this case, the act, citation, and retention periods are clearly identified.

Another approach is to search the laws and regulations directly using online or print resources. Records retention requirements for corporations operating in the United States may be found in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR).

Figure 4.1 Excerpt from Canadian Records Retention Database

Source: Ontario, Electricity Act, FILELAW database, Thomson Publishers, May 2012.

In the United States the Code of Federal Regulations lists retention requirements for businesses, divided into 50 subject matter areas.

The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) annual edition is the codification of the general and permanent rules published in the Federal Register by the departments and agencies of the federal government. It is divided into 50 titles that represent broad areas subject to federal regulation. The 50 subject matter titles contain one or more individual volumes, which are updated once each calendar year, on a staggered basis. The annual update cycle is as follows: titles 1 to 16 are revised as of January 1; titles 17 to 27 are revised as of April 1; titles 28 to 41 are revised as of July 1; and titles 42 to 50 are revised as of October 1. Each title is divided into chapters, which usually bear the name of the issuing agency. Each chapter is further subdivided into parts that cover specific regulatory areas. Large parts may be subdivided into subparts. All parts are organized in sections, and most citations to the CFR refer to material at the section level.2

There is an up-to-date version that is not yet a part of the official CFR but is updated daily, the Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (e-CFR). “It is not an official legal edition of the CFR. The e-CFR is an editorial compilation of CFR material and Federal Register amendments produced by the National Archives and Records Administration's Office of the Federal Register … and the Government Printing Office.”3 According to the gpoaccess.gov Web site:

The Administrative Committee of the Federal Register (ACFR) has authorized the National Archives and Records Administration's (NARA) Office of the Federal Register (OFR) and the Government Printing Office (GPO) to develop and maintain the e-CFR as an informational resource pending ACFR action to grant the e-CFR official legal status. The OFR/GPO partnership is committed to presenting accurate and reliable regulatory information in the e-CFR editorial compilation with the objective of establishing it as an ACFR sanctioned publication in the future. While every effort has been made to ensure that the e-CFR on GPO Access is accurate, those relying on it for legal research should verify their results against the official editions of the CFR, Federal Register and List of CFR Sections Affected (LSA), all available online at www.gpoaccess.gov. Until the ACFR grants it official status, the e-CFR editorial compilation does not provide legal notice to the public or judicial notice to the courts.

The OFR updates the material in the e-CFR on a daily basis. Generally, the e-CFR is current within two business days. The current update status is displayed at the top of all e-CFR web pages.

For governmental agencies, a key consideration is complying with requests for information as a result of freedom of information laws like the U.S. Freedom of Information Act, Freedom of Information Act 2000 (in the United Kingdom), and similar legislation in other countries. So the process of governing information is critical to meeting these requests by the public for governmental records.

Step 2: Specify IG Requirements to Achieve Compliance

Once the legal research has been conducted and a process for keeping updated on laws and regulations has been established, specific external compliance requirements can be listed and those data, document, and record sets that apply to those external compliance requirements can be mapped back to applicable holdings of data sets, document collections, and records series. The crucial task is keeping your legal and records management staff apprised of changes and updating the policies and processes appropriately.

Internal IG retention policies may be different from the legally mandated minimums. For instance, an organization that is not operating in a highly regulated industry that wants to balance defensible disposition with a need to retain corporate memory and develop knowledge management (KM) content or “knowledge bases” may have the option to dispose of e-mail that is not declared a record or cited for legal hold after 90 days, but may choose, based on corporate culture and other business factors, to retain e-mail messages for a year. Similarly, the organization may make legally defensible disposition decisions that reduce the total amount of information it must manage by using a “last accessed” rationale, whereby information that has not been accessed for over one year (or whatever the specified period is) may be destroyed and discarded, as a matter of policy.

Step 3: Create a Risk Profile

Creating a risk profile is a basic building block in enterprise risk management (yet another ERM acronym), which assists executives in understanding the risks associated with stated business objectives and allocating resources, within a structured evaluation approach or framework. There are multiple ways to create a risk profile, and how often it is done, the external sources consulted, and stakeholders who have input will vary from organization to organization.4 A key tenet to bear in mind is that simpler is better and that sophisticated tools and techniques should not make the process overly complex. According to the ISO, risk is defined as “the effect of uncertainty on objectives,” and a risk profile is “a description of a set of risks.”5 Creating a risk profile involves identifying, documenting, assessing, and prioritizing risks that an organization may face in pursuing its business objectives. It can be a simple table chart. Those associated risks can then be evaluated and delineated within a risk or IG framework.

The corporate risk profile should be an informative tool for executive management, the CEO, and the board of directors, so it should reflect that tone. In other words, it should be clear, succinct, and simplified. A risk profile may also serve to inform the head of a division or subsidiary, in which case it may contain more detail. The process can also be applied to public and nonprofit entities.

The risk profile is a high-level, executive decision input tool.

A common risk profile method is to create a prioritized or ranked top-10 list of greatest risks to information.

The time horizon for a risk profile varies, but looking out three to five years is a good rule of thumb.6 The risk profile typically will be created annually, although semiannually would serve the organization better and account for changes in the business and legal environment. But if an organization is competing in a market sector with rapid business cycles or volatility, the risk profile should be generated more frequently, perhaps quarterly.

There are different types of risk profile methodologies; common methodologies are a top-10 list, a risk map, and a heat map. The top-10 list is a simple identification and ranking of the 10 greatest risks in relation to business objectives. The risk map is a visual tool that is easy to grasp, with a grid depicting a likelihood axis and an impact axis, usually rated on a scale of 1 to 5. In a risk assessment meeting, stakeholders can weigh in on risks using voting technology to generate a consensus. A heat map is a color-coded matrix generated by stakeholders voting on risk level by color (e.g., red being highest).

Information gathering is a fundamental activity in building the risk profile. Surveys are good for gathering basic information, but for more detail, a good method to employ is direct, person-to-person interviews, beginning with executives and risk professionals.7 Select a representative cross section of functional groups to gain a broad view. Depending on the size of the organization, you may need to conduct 20 to 40 interviews, with one person asking the questions and probing while another team member takes notes and asks occasionally for clarification or elaboration. Conduct the interviews in a compressed timeframe—knock them out within one to three weeks and do not drag the process out, as business conditions and personnel can change over the course of months.

Here are three helpful considerations to conducting successful interviews.

- Prepare some questions for interviewees in advance and provide them to interviewees so they may prepare and do some of their own research.

- Schedule the interview close to their offices, and at their convenience.

- Keep the time as short as possible but long enough to get the answers you will need: approximately 20 to 45 minutes. Be sure to leave some open time between interviews to collect your thoughts and prepare for the next interview. And follow up with interviewees after analyzing and distilling your notes to confirm you have gained the correct insights.

The information you will be harvesting will vary depending on the interviewee's level and function. You will need to look for any hard data or reports that show performance and trends related to information risk. There may be benchmarking data available as well. Delve into information access and security policies, policy development, policy adherence, and the like. Ask questions about retention of e-mail and legal hold processes. Ask about records retention and disposition policies. Ask about long-term preservation of digital records. Ask about data deletion policies. Ask for documentation regarding IG-related training and communications. Dig into policies for access to confidential data and securing vital records. Try to get a real sense of the way things are run, what is standard operating procedure, and also how workers might get around overly restrictive policies, or operate without clear policies. Learn enough so that you can grasp the management style and corporate culture, and then distill that information into your findings.

Once a list of risks is developed, grouping them into basic categories helps stakeholders grasp them more easily and consider their likelihood and impact.

Key events and developments must also be included in the risk profile. For instance, a major data breach, the loss or potential loss of a major lawsuit, pending regulatory changes that could impact your IG policies, or a change in business ownership or structure must all be accounted for and factored into the information risk profile. Even changes in governmental leadership should be considered, if they might impact IG policies. These types of developments should be tracked on a regular basis and should continue to feed into the risk equation.8 Key events should be monitored and incorporated in developing and subsequently updating the risk profile.

At this point, it should be possible to generate a list of specific potential risks. It may be useful to group or categorize the potential risks into clusters, such as natural disaster, regulatory, safety, competitive, and so forth. Armed with this list of risks, you should solicit input from stakeholders as to the likelihood and timing of the threats or risks. As the organization matures in its risk identification and handling capabilities, a good practice is to look at the risks and their ratings from previous years to attempt to gain insights into change and trends—both external and internal—that affected the risks.

Step 4: Perform Risk Analysis and Assessment

Once you have created a risk profile and identified key risks, you must conduct an assessment of the likelihood that these risks hold and their resultant impact.

There are five basic steps in conducting a risk assessment:9

- Identify the risks. This should be an output of creating a risk profile, but if conducting an information risk assessment, first identify the major information-related risks.

- Determine potential impact. If a calculation of a range of economic impact is possible (e.g., lose $5 to $10 million in legal damages), then include it. If not, be as specific as possible as to how a negative event related to an identified risk can impact business objectives.

- Evaluate risk levels and probabilities and recommend action. This may be in the form of recommending new procedures or processes, new investments in in-formation technology (IT), or other actions to mitigate identified risks.

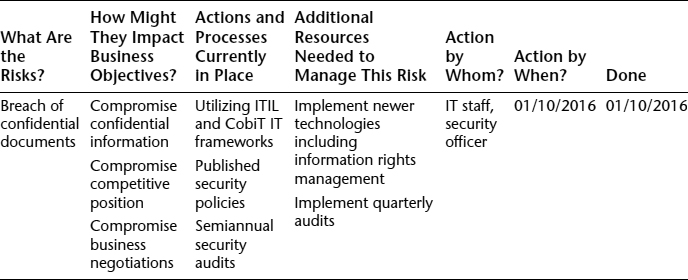

- Create a report with recommendations and implement. You may want to include a risk assessment table (see Table 4.1) as well as written recommendations, then implement.

- Review periodically. Review annually or semiannually, as appropriate for your organization.

A helpful exercise and visual tool is to draw up a table of top risks, their potential impacts, actions that have been taken to mitigate the risks, and suggested new risk countermeasures, as in Table 4.1.

Step 5: Develop an Information Risk Mitigation Plan

After setting out the risks, their potential impacts, and suggested countermeasures for mitigation, you must create the information risk mitigation plan, which means developing options and tasks to reduce the specified risks and improve the odds of achieving business objectives.10 Basically, you are putting in writing the information you have collected and analyzed in creating the risk profile and risk assessment, and assigning specifics. The information risk mitigation plan should include a timetable and milestones for implementation of the recommended risk mitigation measures, including IT acquisition and implementation and assigning roles and responsibilities, such as executive sponsor, project manager (PM), and project team.

The risk mitigation plan develops risk reduction options and tasks to reduce specified risks and improve the odds for achieving business objectives.

Step 6: Develop Metrics and Measure Results

How do you know how well you are doing? Have you made progress in reducing your organization's exposure to information risk? To measure conformance and performance of your IG program, you must have an objective way to measure how you are doing, which means numbers and metrics. Assigning some quantitative measures that are meaningful and do, in fact, measure progress may take some serious effort and consultation with stakeholders. Determining relevant ways of measuring progress will allow executives to see progress, as, realistically, reducing risk is not something anyone can see or feel—the painful realizations are made only when the risk comes home to roost. Also, valid metrics help to justify investment in the IG program.

Although the proper metrics will vary from organization to organization, some specific metrics include:

- Reduce the data lost on stolen or misplaced laptops by 50 percent over the previous fiscal year.

- Reduce the number of hacker intrusion events by 75 percent over the previous fiscal year.

- Reduce e-discovery costs by 25 percent over the previous fiscal year.

- Reduce the number of adverse findings in the risk and compliance audit by 50 percent over the previous fiscal year.

- Provide information risk training to 100 percent of the knowledge-level workforce this fiscal year.

- Roll out the implementation of information rights management software to protect confidential e-documents to 50 users this fiscal year.

- Provide confidential messaging services for the organization's 20 top executives this fiscal year.

Your organization's metrics should be tailored to address the primary goals of your IG program and should tie directly to stated business objectives.

Step 7: Execute Your Risk Mitigation Plan

Now that you have the risk mitigation plan, it must be executed. To do so, you must set up regular project/program team meetings, develop key reports on your information risk mitigation metrics, and manage the process. This is done using proven project and program management tools and techniques, which you may want to supplement with collaboration software tools, knowledge management software, or even internal social media.

But most important, execution of the risk mitigation plan involves communicating clearly and regularly with the IG team on the progress and status of the IG effort to reduce information risk.

Metrics are required to measure progress in the risk mitigation plan.

Step 8: Audit the Information Risk Mitigation Program

The metrics you have developed to measure risk mitigation effectiveness must also be used for audit purposes. Put a process in place to separately and independently audit compliance to risk mitigation measures, to see that they are being implemented. The result of the audit should be a useful input in improving and fine-tuning the program. It should not be viewed as an opportunity to cite shortfalls and implement punitive actions. It should be a periodic and regular feedback loop into the IG program.

CHAPTER SUMMARY: KEY POINTS

- In identifying information requirements and risks, legal requirements trump all others.

- In the United States, the Code of Federal Regulations lists information retention requirements for businesses, divided into 50 subject matter areas.

- The risk profile is a high-level, executive decision input tool.

- A common risk profile method is to create a prioritized or ranked top-10 list of greatest risks to information.

- Once a list of risks is developed, grouping them into basic categories helps stakeholders to grasp them more easily and consider their likelihood and impact.

- The risk mitigation plan develops risk reduction options and tasks to reduce specified risks and improve the odds for achieving business objectives.

- Metrics are required to measure progress in the risk mitigation plan.

- The risk mitigation plan must be reviewed and audited regularly and proper adjustments made.

Notes

1. Ontario, Electricity Act, FILELAW database, Thomson Publishers, May 2012.

2. U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), “Code of Federal Regulations,” www.gpo.gov/help/index.html#about_code_of_federal_regulations.htm (accessed April 22, 2012).

3. National Archives and Records Administration, “Electronic Code of Federal Regulations,” http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&tpl=%2Findex.tpl (accessed October 2, 2012).

4. John Fraser and Betty Simkins, eds., Enterprise Risk Management: Today's Leading Research and Best Practices for Tomorrow's Executives (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), p. 171.

5. “ISO 31000 2009 Plain English, Risk Management Dictionary,” www.praxiom.com/iso-31000-terms.htm (accessed March 25, 2013).

6. Fraser and Simkins, p. 172.

9. Health and Safety Executive, “Five Steps to Risk Assessment,” www.hse.gov.uk/risk/fivesteps.htm (accessed March 25, 2013).

10. Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide), 4th ed. (Project Management Institute, 2008), ANSI/PMI 99-001-2008, pp. 273–312.