Chapter 3

People matter

Imagine that you’re visiting your friend’s house for the first time. After a while, you need to use the bathroom. Since this is your first time there, you clearly don’t know where the bathroom is, so you wouldn’t dare wander around to find it. Instead, you would ask your friend and you would need him or her to show you around. It’s the same at work. You need the people already working there to show you around.

Regardless of the type of organisation you work for, having great relationships with the people you work with and for is extremely important. This is probably one of the biggest differences between work and school. When I use the word ‘relationship’, I don’t mean just being able to ‘get along’. Instead, I’m referring to the type of relationship where a colleague is willing to look out for you, open up to you, tell you how the environment works and tell you when you do something well and when you don’t. This is someone who will introduce you to important people in the organisation, create opportunities for you and pound the table for you when you’re not in the room where bonuses, salary increases, promotions and step-up opportunities are being decided. This person is someone who will coach and mentor you and school you on the unwritten, unspoken rules of the company. Ideally, this is someone who will want to see you win and who will do his part to make sure that happens, because he understands you and wants to invest in your success. In your workplace, who is excited about you? Do any of your seniors know of your skills? Know your story? Consider this: how can someone be excited about you if no one knows you? Remember that you will not be in the room when the most critical decisions that affect you and your career are made, so you cannot lean solely on your intelligence to help you stand out from the crowd.

Relationships are the cornerstone and foundation of business. Whether it’s the relationship between you and your teammates, your manager, your company and its customers, clients or suppliers, or between you and the CEO and the board of directors, relationships matter most. Every business sells something or provides a service to people, and every job within it is enabled or performed by a person or persons. If you look at your job through this lens, you will take a totally different approach to your work.

We often talk about hard work as an ingredient for success and I firmly believe that it is. But when we speak of it, we usually speak solely about putting in the long hours and making sacrifices in order to master our craft and be excellent. However, I’d like to challenge you to think more broadly. Hard work also includes the energy and effort you put into building and sustaining your working relationships.

| In 2014, after a spell of unemployment, I got the job of my dreams at a well-known professional services firm. This was the third time I had applied for that job, so I was convinced this was it! But five months later, the relationship between my manager and I had broken down and I was under performance management, even as my internal customers praised my work.” |

The above quotation is taken from a post on the blog Working While Black. When I first read the post, it made me wonder: what could this person have done differently to make the relationship with his/her manager an asset rather than a liability?

| The secret to success, whether it’s an individual or an organisation, is down to people. That was always the bits that made the difference.” – Thokozile Lewanika Mpupuni |

From my experience working with young professionals, I’ve noticed that, instead of focusing on relationship-building, Black people across the globe are often obsessed with degrees. When I started working at McKinsey, my mother’s first question to me was: ‘How many degrees does your manager have?’ My hypothesis is that we have been socialised to believe that degrees, certifications and qualifications are the only things that matter. We have been socialised to think that they will take us wherever we want to go in our careers. While your intelligence, qualifications and degrees are the price of admission to an organisation, the key driver for advancement and success in your company is relationships. The better you are at building and maintaining relationships, and at working with others, the more successful you’ll be.

I also believe that many of us spend a lot of energy getting those degrees, and then, when the time comes for us to start the job, we have very little energy left to work on our next challenges – many of which we didn’t know even existed. It is as if someone moved the goalposts midway through the game! Understandably, we can become frustrated, but, to be honest, the rules governing corporate environments have always been the same. You just didn’t know them. This is the consequence of being marginalised, of standing on the outside looking in. Because nobody told us the rules we made them up, and the ones we made up were all about degrees. We need to acknowledge the insufficiency of this belief.

One of those major challenges (those ones you perhaps didn’t know existed) is building relationships. In Chapter 1, I discussed the concept of working in versus on your career. This concept also applies to our relationships. Working in your relationships includes the activities that you and your team members or manager engage in to get the work done. They include the following:

![]() Establishing expectations and project goals (ie, what does success look like?)

Establishing expectations and project goals (ie, what does success look like?)

![]() Discussing the status of projects (What are the key milestones? What progress has been made to date?)

Discussing the status of projects (What are the key milestones? What progress has been made to date?)

![]() Understanding resources needed (What do I need to complete this project?)

Understanding resources needed (What do I need to complete this project?)

![]() Establishing and negotiating timelines (When is the project or task due? Can I push the deadline back? Can I have more time?)

Establishing and negotiating timelines (When is the project or task due? Can I push the deadline back? Can I have more time?)

![]() Unpacking obstacles (What is hindering you from completing the project?)

Unpacking obstacles (What is hindering you from completing the project?)

![]() Determining key stakeholders (Who do I need to consult and keep informed during the course of this project? Who has a keen interest in how this work is done? Who will be impacted by my work? Who can influence the success or failure of this project?)

Determining key stakeholders (Who do I need to consult and keep informed during the course of this project? Who has a keen interest in how this work is done? Who will be impacted by my work? Who can influence the success or failure of this project?)

Working on your relationship, however, involves taking a step back to understand, manage and enhance the dynamics of your working relationship(s) with your colleague(s). It includes considering the following questions:

![]() How is each of us feeling about the work?

How is each of us feeling about the work?

![]() What stresses and pressures are each of us under?

What stresses and pressures are each of us under?

![]() Do I feel that my colleague cares about me as a person? Does my colleague feel that I care about him/her?

Do I feel that my colleague cares about me as a person? Does my colleague feel that I care about him/her?

![]() Do I feel that they want me to be successful? Do I want them to be successful?

Do I feel that they want me to be successful? Do I want them to be successful?

![]() Do we feel supported to meet and exceed the expectations?

Do we feel supported to meet and exceed the expectations?

![]() How do we feel about our interpersonal dynamic (how we communicate in person or via email)?

How do we feel about our interpersonal dynamic (how we communicate in person or via email)?

![]() Do we have unaddressed tension in our relationship(s)? If so, how should we handle it?

Do we have unaddressed tension in our relationship(s)? If so, how should we handle it?

![]() Do I understand what my partner’s areas of development, strengths, values, trigger points, etc are? And does he or she understand mine?

Do I understand what my partner’s areas of development, strengths, values, trigger points, etc are? And does he or she understand mine?

![]() How do I feel after having an interaction with my colleague? And vice versa? Do either of us feel demotivated, anxious, uninspired, de-energised? Or do we feel motivated, peaceful, inspired and energised?

How do I feel after having an interaction with my colleague? And vice versa? Do either of us feel demotivated, anxious, uninspired, de-energised? Or do we feel motivated, peaceful, inspired and energised?

Working on your relationships highlights an important point: often, we don’t want to address interpersonal dynamics. We just want to focus on the work. But it’s important to remember that the quality of our output and the general outcome of a task correlates with the quality of our relationships. I have been super guilty of this in my career, exactly because I didn’t understand the connection between my work and my relationships. In the past, I used to set aside any negative interpersonal dynamics and focus all of my energy on the outcome. A part of me didn’t think that relationships were important: if the product was great, all that other stuff didn’t matter. What I quickly learnt, though, was that ‘the other stuff’ never went away. In fact, negative relationships just got worse.

If you and a colleague get along, he or she will be more willing to help you, which means that you don’t have to spend any of your energy thinking about, trying to avoid or unpacking the tension between the two of you. With a good relationship in place, you can focus all your brain power on solving the problem. (Anyway, who wants to come to work every day and deal with passive-aggressive comments, tension and side-eye?) In order to get to this point, you might have to put your agenda and that project aside to discuss the working dynamic between you and your teammate and/or manager.

Working In vs Working On Your relationships

Working in your relationship discussion topics | Working on your relationship discussion topics |

|---|---|

• What are the project due dates? | • How do I feel about the work? |

• What are the roles and responsibilities? | • Do I trust you? |

• What are the specific tasks that need to be completed? | • Is there unresolved conflict in our relationship? |

• What are the critical project milestones? | • Do I feel as though I am being properly supported to get the work done? |

• What roadblocks am I encountering? | • Do I feel that the expectations from the other side are fair? |

• What resources and support do I need? | • What are your emotional trigger points? |

• How often will we meet to discuss the project’s progress? | • What are you trying to achieve? |

• What elements of the project do you want to be kept abreast of? And with what frequency would you like these updates? | • What are your strengths? • What are your areas of development? |

• Should I bring an agenda to those meetings? | • What influences you the most when you are making decisions (data, vision, process to achieve, who else supports the idea, etc)? |

From theory to practice

One of my former coaching clients is a senior executive at a branding and marketing firm. She told me that she does not trust or connect well with a certain member of the board of directors of her company. The lack of trust between them, she said, affected their ability to communicate effectively and exchange ideas in a mutually beneficial way.

‘What does this board member value?’ I asked her.

‘Money, numbers and financials,’ she responded.

‘And what do you value?’

‘I value leadership. When I communicate with him, I speak about numbers and financials because I know that is what matters to him. I don’t feel like he makes the same attempt.’

‘Let’s switch gears for a second,’ I replied. ‘Tell me about your business partner. I know you’re close to her.’

‘She’s very different from me. I’m much more “big picture” and she is more into the details. She wants to know the metrics and important numbers that are associated with whatever I want us to do. Once I talk to her in the language that is most important to her, then we can talk about the areas that are important to me.’

So I asked: ‘How did you get to this point with her, especially since you are so different?’

‘We’ve known each other for seven years,’ she said. ‘She’s like a sister to me. We have a great relationship.’

‘So, since you’ve been working in this business, how much time have you spent building a relationship with that board member? Have you ever had a non-work-related conversation with him? Have you ever gone for coffee or lunch to understand who he is, his journey and why he values what he values?’

She looked at me sheepishly. ‘No.’

‘If you don’t trust him, he isn’t going to trust you either,’ I said. ‘He can sense that you don’t trust him regardless of whether he has said anything or not. Regardless of how professionally and respectfully you have communicated with him, people can sense vibe, energy, body language and tone. People have to trust you before they trust your ideas. So if you want to maximise your impact in this company, then you’ll have to take the first step to build and repair this relationship. You’re going to have to start to understand who he is, what his story is and why he values what he values.’

I continued: ‘Relationships matter most in business and that trust is the most important factor in those (or any) relationships. If trust is lost, then the working relationship is doomed and you’ll never be able to have the impact that you want to have until you fix it. Building or repairing this relationship should be your numberone priority. Take time away from your to-do list and spend time on this. Make the sacrifice of time in the short term and it will benefit you, your team and the organisation as a whole in the long term.’

As with anything in life, your approach to relationships starts with your mindset. Here is a perfect example. I was speaking with a young Black professional who was about to start a new job at a global management consulting firm. I asked her how she was feeling about the job, and she said: ‘I’m nervous because this is the first job I’ve ever had where I have to get people to like me. I’m also someone who has a lot of pride, so . . .’ I finished the sentence for her: ‘So you don’t want to have to grovel to get people to like you.’ I told her that if she wanted to be successful in her new role, she had to think about it in a different way. It’s not about getting someone to like you. It’s about building a mutually beneficial relationship where each party adds value to the other person. The senior person adds value by mentoring and coaching you and giving you feedback, and you, in turn, add value by giving that person an audience for their experiences and maybe an extra set of hands when they need help on a project. Because of the relationship that you’ve now cultivated with that person and the quality of work you deliver, that person will be more than happy to pound the table to support you during performance reviews and recommend you when step-up opportunities arise.

| It’s important to remember that a person is a network, not an individual. So always treat people as a network and not as an individual. So you have to leave that relationship in a way that’s good enough that if they ever have influence over you in a different scenario or through other people, you would still leave a positive impression with them no matter how hard it is.” – Thokozile Lewanika Mpupuni |

I’ve seen a lack of relationships keep people from promotions they rightfully deserved. On the flip side, I’ve also seen how relationships help people keep jobs that they should have been fired from long ago.

| I tried to understand and collaborate with a lot of the departments. I tried to understand how my work affected others, and vice versa. This led me to having a great network internally and externally. Nurture those relationships always, even after you’ve left. You want to leave a good name wherever you go.” – Nomfanelo Magwentshu |

Relationship currency evolves over time. When you first start a job, building your relationship currency means that you have to get to know people and allow them to know you, so that they will show you the ropes and invest in your development. The first person you want to build that currency with is your direct manager. However, don’t stop there: build relationships with your teammates. They might have skills that you don’t, or maybe they’ve been there longer and can help you understand the culture, the expectations and how the organisation works. Plus, having friends at work makes work more enjoyable. Some of us spend more time with our colleagues than we do with our families and friends, so it stands to reason that you would want to have real, genuine, authentic relationships at work.

If you become a manager, your relationship currency will extend to the people who report to you. As a manager, your job is to achieve results through others, but if you are a horrible manager with a high attrition rate – if you’re constantly recruiting, rebuilding and training a new team – you will never be as effective or impactful as you would like to be. And, even with peers on a managerial level, you want to be able to show up to work every day and have positive interactions with them. If you become part of what is known as ‘the C-suite’ (positions such as Chief Executive Officer, Chief Human Resources Officer, Chief Financial Officer, etc), you’ll need to develop great relationships with your direct reports as well as your company’s board of directors. Show me a company that is not performing well and I’ll show you how poor relationships have contributed to the breakdown of that business.

| Engage with others and understand each one’s journey and not just in the formal environment. Engage in the formal and informal environments. In the lift. At the coffee station. In the parking area. In the informal oneon-one feedback. Just be open to interacting and engaging with people. You will learn more about them and you will learn a lot more about yourself in the process.” – Nomfanelo Magwentshu |

If building relationships comes naturally to you, congratulations. For those of us who don’t naturally think about doing this, building relationships has to be an intentional decision and a goal. I am naturally more of an organic relationship builder. I just let it happen, as opposed to being intentional about it. I am also someone who has a natural preference for action and execution. Getting things done energises me, so I am always focused on the task at hand and love checking items off my to-do list. However, over the years I’ve realised that I needed to intentionally set aside some time to get to know people and for them to get to know me.

In preparation, I asked myself two crucial questions: first, what are my boundaries, and, second, what small steps outside my comfort zone am I willing to take to build relationships? In other words, what am I unwilling to sacrifice in order to build relationships? And which of my preferences and aspects of my usual way of being am I willing to sacrifice? I realised that I have one main boundary: I wasn’t going to be dishonest in an effort to build relationships, nor was I willing to spend time building relationships with people who clearly weren’t interested in building a relationship with me. Other than that, I was willing to make adjustments and be flexible.

For example, during my time at McKinsey, I shared an office with two other people. Colleagues would often come into the office to speak to one of my office mates about work-related matters, but, because of my natural bias for action and my almighty to-do list, I would greet them and then turn around to keep working. However, I decided that if a colleague came in just to chat socially, I would turn around and join the conversation as well. It didn’t cost me anything except a few minutes away from my to-do list. In addition, it gave people an opportunity to get to know me and for me to know them. I gave them a chance to access me in a nonbusiness, non-task-affiliated way. It helped people see a different side of me, and vice versa. In the long run, these short interactions made future business interactions easier, exactly because we had established rapport beforehand.

What are your non-negotiables? Is everything on your list nonnegotiable? When and how can you be a little more flexible? Are you willing to make compromises? Keep in mind that if everything is important, then nothing is. An easy step that you could take is to eat lunch in the break area with your teammates instead of at your desk. Are you willing to sit with people that you don’t know? Could you spend a bit more time at the coffee machine if a colleague is engaging you? Are you willing to sacrifice a bit of your Netflix time to join office drinks on a Friday or at the monthly networking event? Start small, but start somewhere.

| Networking is about genuinely being interested in people.” – Jocelyne Muhutu-Remy |

Building relationships is a skill. Trust is the primary foundation for any personal or professional relationship.

One of my favourite Harvard Business School professors, Frances Frei, says that trust is made up of three components: logic (‘Are you competent?’), authenticity (‘Are you real?’) and empathy (‘Do you care about me?’). There are two key takeaways from this formula. First, a deficit in any one element affects your overall trust level. And, second, the more your actions seem focused on and about you, the less trusted you will be. If you ever have a relationship that you are struggling to make work, look at one of these elements to see what the root cause of your issue might be.

When you’re deciding what you will share to build trust, I’m not suggesting that you reveal your deepest, darkest secrets. But be willing and be prepared to share some side of yourself that is not connected to work to help you connect on a human level with the people you work for and with. Be vulnerable to a level that you’re comfortable with. It draws people to you. It humanises you. It helps people be honest with you. Plus, knowing your human side makes people want to invest more in you. Consider this: when was the last time you trusted someone you knew nothing about?

| Who are the people you need to collaborate and work with to deliver value for your company? Know who is in that value-creation chain of your world and connect with them authentically, because there’s nothing more off-putting than that transactional newbie. Every time you go to someone, it can’t just be because you want something from them. Take an interest in and facilitate the success of others.” – Thokozile Lewanika Mpupuni |

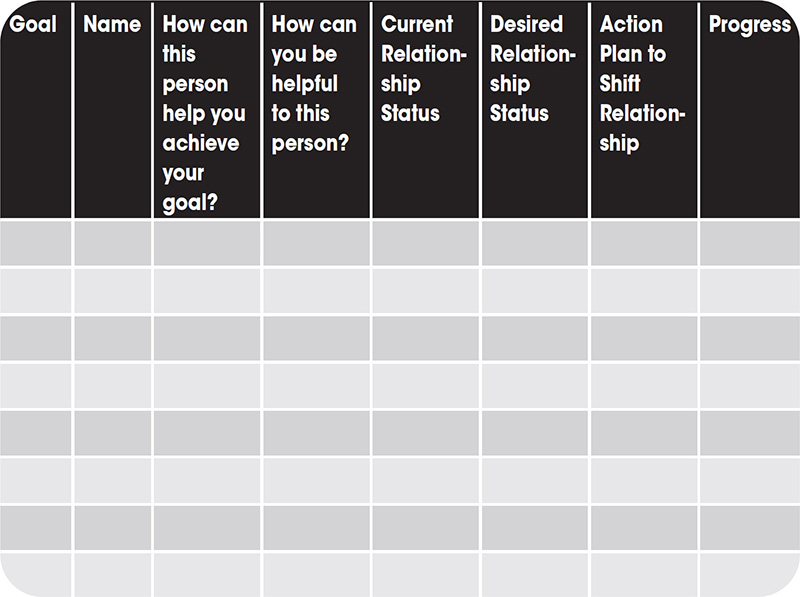

Determine what you want to achieve and what type of support you need to achieve those goals. The next step is to determine the key stakeholders and what type of support you need from each person. Use the relationship-building plan template below to organise your thoughts on those key relationships.

Working In vs Working On Your relationships

Keys to building great relationships

Now that you know who you want to build great relationships with and what support you need, let’s focus on four key elements that will help you do just that.

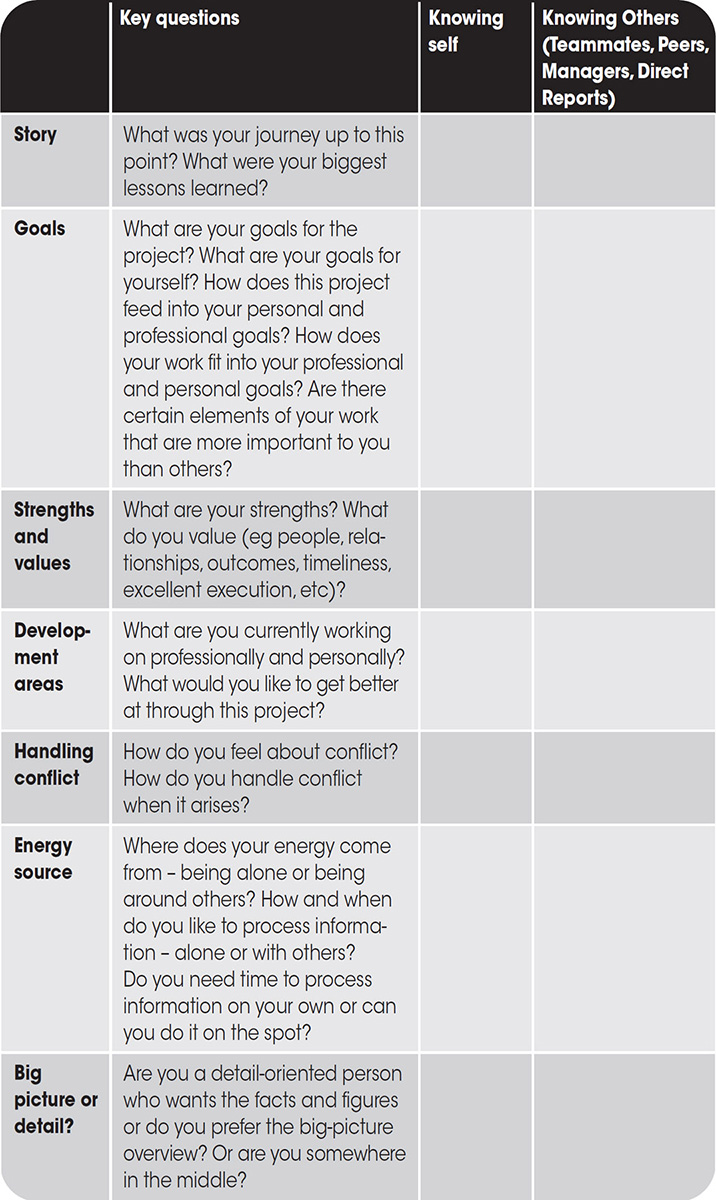

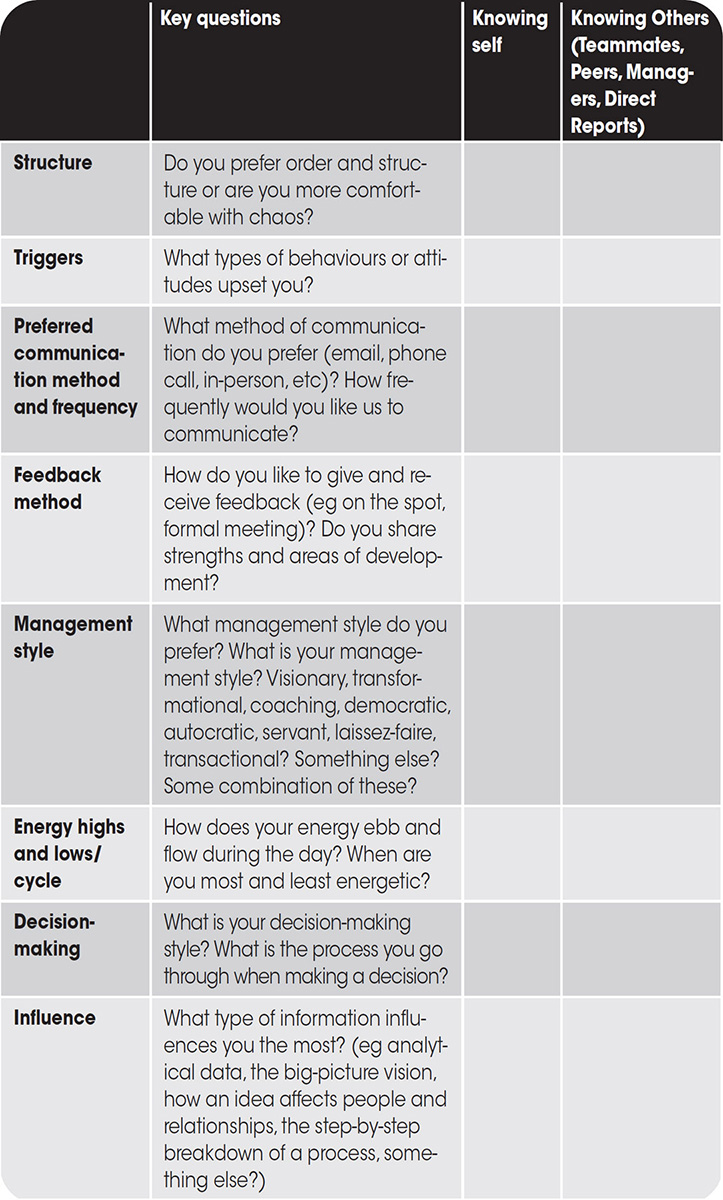

1. Do your due diligence: We often assume that others are just like us, want the same things or will automatically know what we want. We tend to play this game of assumptions and wait until conflict or tension arises between ourselves and others. Wouldn’t it be better if we had conversations upfront to communicate what each person needs and wants so that we could be more intentional about how we interact? On page 125 there are 17 topics that we can discuss upfront to better understand the individuals that we work for and with.

In an ideal world, you want to know what your preferences are so that you can communicate them to your manager. If you’re early in your career and still learning what your preferences are, spend this time learning how your manager operates. Once you and your manager have shared your preferences, see how big the gap is between you and this person. The bigger the gap, the harder you will have to work to make the relationship work. Keep in mind that these questions do not have to be answered in one sitting. Take a few sessions to discuss them. They can also be posed to a team member that you are trying to build a relationship with. Another great source of information is to speak with people who currently or previously worked with your manager or teammate.

2. Be accessible: This may sound like an obvious point, but in order to build a relationship, you have to be available – quite literally – for those conversations. You have to work on your relationships with your colleagues, which means you have to create space and time for you to get to know each other. I know it can be difficult if you are the only Black person, the only young person or the only woman at work: I’ve been in those circumstances as well. It’s just easier to go and sit with the people in the break area who look like you, speak the same language and come from the same culture. But does that help build the necessary relationships that you need to be successful and have maximum impact? No, it doesn’t. This doesn’t mean that you can never sit with those who look like you; what I’m saying is that you can’t do that all the time. Life is about stepping outside your comfort zone, and you’re never going to grow if you stay firmly within its boundaries. Growth is inevitably about discomfort, so if you want to grow, be prepared to be uncomfortable sometimes. Is it hard? Yes. Does it suck? Sometimes. Is it unfair that you have to and others don’t? Absolutely. Does it still need to be done? Yep.

| People have a yearning to see themselves in others, to mirror each other. Sameness gives us a sense of belonging, a sense of safety, reduced anxiety, cognitive rest and optimal survival. Diversity poses a risk, because anybody that looks different may be a threat to our well-being. The brain is extraordinarily drawn to sameness for survival. In a corporate world, our evolutionary biology of being attracted to sameness doesn’t always serve our social goals. So if you want to serve your social goal of being more inclusive and diversifying, you’ve got to override the brain’s desire to stay in the same group.” – Timothy Maurice Webster |

3. Be curious, and listen: We often use our time to share something about ourselves, but sometimes we need to ask questions and learn about others. A good tip to building great relationships at work is to show genuine interest in who your colleagues are: where they come from, how they got to where they are now and what they care most about. We celebrate those who can string words together eloquently in TED talks or on social media, but we rarely celebrate the skill of listening. Let’s differentiate between hearing and listening. Hearing is passive and involuntary. If you do not have a hearing impairment, you will be able to perceive sounds. Listening is active, voluntary and requires concentration. Listening requires you to engage your brain and process meaning and generate questions based on what the other person is saying. You can’t be a great communicator without being a good listener. Everyone wants to be heard and supported in terms of how they experience situations and people. This skill will also help you tap into what is most important to that person. This knowledge can help you shape your messaging so that it appeals to who you’re talking to and what they’re trying to accomplish. People enjoy sharing their stories and they’ll open up even more if you demonstrate genuine interest in learning more about them and appreciation for what they bring to the table.

Before you start a conversation with someone, ask yourself whether you’re truly open to listening to what the other person has to say. Are you willing to expand your thinking or are you merely looking for an opportunity to validate your opinions? During a conversation, you need to listen to what the person is saying and how they are saying it, and to pay attention to his or her body language. You shouldn’t be simply thinking of what you’re going to say next or waiting for the person to take a breath so that you can insert your point into that gap.

In a July 2016 Harvard Business Review article titled ‘What Great Listeners Actually Do’, Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman show that great listeners don’t just silently sit there or repeat word for word what someone else has said. Instead, good listeners ask thoughtful questions that clarify assumptions, and they ask questions that let the speaker know that they have understood what was said. They even ask additional questions to gather further information about what the speaker has said. Great listeners are empathetic and acknowledge the feelings and emotions of others. Make sure you’re in the right frame of mind to listen; if you’re not, move the conversation to another time when you’re in a better headspace. Stay open and don’t make assumptions. Practise listening even when it is painful to hear what the other person is saying. What emotional baggage do you have that keeps you from staying in the moment and listening to what the other person is saying? I believe poor listening skills, combined with our own baggage, keeps us from listening, especially when we’re in a conflict situation or when we’re receiving feedback. We listen through the filter of our baggage. You and someone else can hear the same statement but interpret it differently because of your experiences and perceptions. When someone challenges you or gives you feedback, does it dredge up emotions from people and situations in your past? If so, that is your baggage. Spend some time unpacking it.

4. Grow your empathy: Being able to understand the context, situation and associated feelings that a person has is critical to building rapport and relationships with others. A prime example is when a leader in a company acquires a new client and then approaches a consultant to see if he or she might want to work on that particular business project. I used to tell consultants that before they said ‘no’ with a disgusted look on their face simply because they’re not interested in the project, they should think about all the effort and months of work it had taken for that leader to close the deal. I encouraged consultants to think about all the back-and-forth those senior leaders probably experienced; how could they, as consultants, have the nerve to tell the leader in such a dismissive way that they weren’t interested? It’s similar to someone telling a new mother that her baby is ugly. Whenever I used that analogy, people seemed to get it.

I am not telling you to feign interest in a project. Rather, I encourage you to think about how you convey a message. You can honour your truth and the efforts of the other person in a way that fosters the relationship and does not tear it down. Empathy, like any skill, is something that you can develop. Start by practising empathy in small ways. When starting a new project, take a few minutes and put yourself in the shoes of your teammate or manager. Think about the context of that person’s reality, all that the person is balancing and feeling, and how your work fits into that person’s overarching goal.

| With empathy you can reach anyone.” – Jocelyne MuhutuRemy |

The reality about managers

Years ago, I worked for a manager with whom I never really gelled. After a few years working for her, our entire team took the CliftonStrengths Assessment (which I describe in Chapter 2). When I compared my results with hers, I realised that the heart of the reason why we didn’t get along was that we did not have the same strengths, which meant that we did not value the same things. We were basically on opposite sides of the strengths spectrum.

When you and another person don’t value the same things, there is a good chance that there will be tension. Now, what if I had known that at the beginning? We probably would have had a completely different working relationship. I would have known that I needed to work harder to bridge the gap between us. Maybe I would have been able to influence her more had I appealed to her in areas that she valued. Maybe I would have volunteered to help her in areas where I knew that I was stronger, instead of being frustrated when she didn’t do the things I expected her to do well. Had I valued her strengths, maybe I would have tried harder to learn from her in those areas. Maybe we would have had a better relationship if she felt that I valued what she brought to the table. Ultimately, not trying to understand each other’s differences got in the way of our having a fruitful working relationship.

In most conventional corporate settings, your manager has a tremendous amount of influence over your career, your on-thejob training, your development opportunities and how others in the organisation perceive you. Remember that your manager is not just a manager: he or she is a human being with fears, insecurities, triggers, strengths and weaknesses. Regardless of how senior, how talented, how tenured your manager is, or how confident they may seem, they may have deficiencies in areas that will affect, annoy or even anger you. Sometimes you might even find it difficult to identify anything to respect about your manager.

Because many of us (including myself) have grown up with such a focus on competence, and because we’re told that we have to be great at our jobs, we assume that everyone in a leadership position deserves their position, based solely on their competence. I had to learn the hard way that adults are in positions for many reasons and sometimes those reasons have absolutely nothing to do with competence. Sometimes people get (and keep) jobs because of their loyalty to the organisation. Other times, a person has a certain job because she has great relationships with senior people who would never fire or demote their friend, no matter how incompetent that person is. And even if your manager is competent, he or she may not bring everything that is needed to do the job well. But remember: your manager is also trying to survive, navigate and thrive in the same complex world as you. Be sensitive to that and spend time trying to understand this person.

I’m sharing this so that you can manage your expectations about the quality of your manager. I know I’ve had high expectations of my previous managers, and when they didn’t meet my expectations, I found it hard to build relationships with them. My advice is to work hard to find something you can respect about the person – be it education, their path to their current position, tenacity, work ethic, knowledge about the organisation, their network, their ability to build and maintain relationships, their sense of humour . . . something, anything. Your respect for the person needs to emanate from a genuine place; if not, it will have the opposite effect and your relationship will disintegrate.

| Make good friends at work. Don’t make your co-workers your enemies. Make them your allies. Find that one good ally.” – Zimasa Qohole Mabuse |

One of the biggest surprises in my career has been how each company, culture and set of circumstances that I have chosen to be in has taught me something about myself that I didn’t know. Sometimes these revelations appeared quite subtly. Sometimes I didn’t even see them until I reflected on the situation. And sometimes they popped up in an unprofessional way because I was not sufficiently managing my emotions, which led to my work relationships going south. The coaching I’ve received, the personal reflection that I’ve done and the assessments that I’ve taken have given me a window into a better understanding of myself. Once you are armed with that self-knowledge, you are no longer taken off-guard when a situation triggers you because you’ve ‘seen this movie before’. You don’t react without thinking because this situation is familiar to you and you know how to manage it. It’s better to continue to learn the lesson of you, because if you don’t, you’ll repeat the same mistakes and wonder why you keep getting the same outcomes.

Once, during a one-on-one meeting with my manager, she turned to me and said: ‘I feel like you don’t trust me.’ I was shocked, because I thought I was being professional and respectful, so I could not for the life of me understand how this person could sense anything was wrong. I had not spent a lot of time examining how I felt about her, but clearly she had detected what I hadn’t even realised or admitted to myself. I had two choices in that moment: I could either tell the truth or I could lie. It would have been easier to lie because then I wouldn’t have to face the elephant in the room. I wasn’t sure of the repercussions if I told her the truth. Would I be on the fast track out of this company? Would she be angry, upset? Would she start crying? Regardless of the possible outcomes, I decided to exercise courage. I chose to tell the person the truth. I looked at her and admitted: ‘I don’t trust you.’ The person responded: ‘Is it a values issue or is it that you don’t believe that I have the team’s back?’ ‘I don’t believe you have the team’s back,’ I said.

What I realised at that point was that any person can sense tension and whether or not you like, trust, value or respect them. I learnt that people sense your energy, your body language and your tone, and that I wasn’t fooling anyone. It was a big lesson for me. If I knew that I wasn’t fooling anyone or hiding how I felt, I might as well have been honest with myself and unpacked my emotions about the person. If I had done that, I would have had to address those issues head-on in a respectful and thoughtful way with my manager. From that point forward, if I had an issue with my manager (or anyone else), I decided to address it as soon as possible. Remember that the person may never articulate that she or he knows you don’t like him or her; nevertheless, that person knows it and will proceed to interact with you in a way that is based on that knowledge. Pretending as if your feelings are not what they are doesn’t work. Hoping that the problem goes away also doesn’t work. In many ways, and in most situations, it just makes it worse.

Managing up

One of the first and most important relationships that you should invest in is the one with your direct manager. One of your goals should be to make your manager’s work life easier. The better the relationship you have with her and the more you understand her, the easier it will be for you to achieve that goal. You want to make your manager feel that you are on top of things and that you are communicating proactively with her before she even asks. The more she feels like you are on top of things, the more autonomy she is likely to grant you.

Just imagine what a powerful impression you could make on your manager if you said the following to her at the outset of your relationship: ‘Having an effective relationship with you is a big priority for me. I want us to work as best we can as a team and as part of the larger team. So I would like to sit down with you and discuss how you like to work and what you’re expecting of me. I would also really love to hear more about you and your professional journey. There is so much I can learn from you, so I would love for us to grab a cup of coffee, schedule lunch or for me to shadow you. Please let me know if you would be open to this and the best way for me to get on your calendar.’

‘Managing up’ means creating mechanisms and ways of working that honour what you’ve learnt about your manager during the Relationship Conversation Starters exercise. If you know that your manager is a big-picture thinker, as opposed to someone who is focused on the details, communicate the big picture in your emails and presentations and then bring attention to the details afterwards. If your manager doesn’t like to digest information in the moment, plan your work so that you can send her the document the night before to give her time to formulate her thoughts. If a certain project is high-priority for your manager, create recurring weekly calendar invites with her so she can be kept abreast of any updates. Bring agendas to your weekly or semi-weekly meetings and make sure you first cover the items your boss cares about, just in case you run out of time. Use this time to problemsolve with your manager or alert her to obstacles that you’re running into. Alert your manager immediately to pressing issues that simply can’t wait. Bring proposed solutions to her, not just problems.

Check in with your manager to make sure that your plan and approach are still working and adjust as necessary. Projects and priorities shift. What your manager cares about today may change tomorrow. Maybe your manager was fine with biweekly check-ins for your previous project, but now she may want weekly check-ins because the stakes are higher.

Managing conflict

If you start to feel that there is unaddressed tension in any of your work relationships – with your manager, peers, clients or any stakeholder that is key to your delivering your work – address it. It doesn’t have to be a dramatic conversation. You can simply say, ‘I’m sensing some tension between the two of us and I really want to talk through it. Is there something that I have said or done that is causing the tension? If so, please tell me what it is so I can address it.’ As a junior employee, this type of tension has a disproportionate impact on you and your work, so it behoves you to step up and initiate the courageous conversation. So many young people just hope that conflict, hurt feelings and tension will magically go away. On the surface we say, ‘Oh, it’s fine. It’s not a big deal. I’m over it.’ But, secretly, we are noting each offence, each slight and each misstep in our mental notepad. I call it the SLOO – the Secret List of Offences. With every addition to the list, the offender digs a deeper and deeper hole that becomes harder and harder to get out of. With every slight, the gap widens between you and the other person until it reaches a point of no return.

We often make assumptions about people’s behaviours, motivations and intentions, and nine times of ten our assumptions are negative. Usually, we don’t give people the benefit of the doubt. And the longer the list of offences grows, the more sinister the spin is that we put on our assumptions. There is a chance that you are the type of person who sincerely gets over things and moves on, but if you aren’t, it’s best to address those issues and give others the opportunity to explain their side of the story. Even after hearing from the other person, you still may not like what he or she has to say, but at least you’ve given them a chance to share their perspective. And maybe, just maybe, you were wrong and the person’s behaviours and motivations were not what you thought they were. All of this helps to lessen – or even close – the gap. This will help you establish a genuine working relationship with that person, instead of you just saying the right words to make the person believe that the relationship is good.

When we don’t address conflict, one of two things is likely to happen at some point. We either explode because we can no longer suppress our feelings of hurt, anger, disappointment or betrayal, or we completely mentally cut off the other person. There are obvious career-limiting consequences that come with exploding in anger at your manager. Cutting someone off might be much less destructive, but people will usually sense your feelings even if they don’t verbalise them. Unfortunately, this will create an invisible wall between you and the other person, and he or she might no longer want to actively contribute to your development, growth and advancement in the organisation.

Sometimes we have to work with people that we don’t have natural chemistry with or that we don’t like or respect. We have to find a way to make the relationship work, because you’re not going anywhere and neither is the other person. Before you know it, you and the other person have characterised each other in such a negative way that it becomes increasingly more difficult (read: impossible) to close the gap or to even return to a point of neutrality. You have to figure out what type of person you are in conflict: do you have a fight, flight or freeze response? Fight people become more controlling and aggressive. Flight people run from the situation in fear and want to be left alone. Freeze people just stand still and they look okay but they are not comprehending or engaging.

When someone offends you, the first thing you need to do is ask yourself: ‘Am I bothered by what happened? Or am I bothered by something else?’ The worst thing you can do is to take your frustrations about another situation out on your colleague. If you reflect and realise that the issue is not important enough to raise, then you should move on. If you decide that you are bothered by the offence, you have three options: ignore the offence and have a gap develop between you and the other person; raise the issue and address it with that person; or decide that the issue is not important enough to address and genuinely move forward.

Over the course of my career, I have sometimes done this well and sometimes very poorly. These have been some of my biggest lessons. What has worked for me was to create some space between me and the other person so that I could calm down and think about what was going on between us. I would reflect on what I didn’t know about the person or the situation, what my role was in that tension, what I was willing to give up, how I could change my thoughts and behaviour, and what I needed from the other person for the relationship to move in a more positive direction. Then I would approach my colleague. In addition to sharing how I felt, I would make sure to ask questions, as opposed to making statements or assumptions, about how he or she felt or why he or she behaved in a certain way. Another crucial technique is to pause the conversation. Maybe it’s for ten seconds, ten minutes, a day or a week. If the conversation is getting too heated, it’s okay to step away so that one or both of you can calm down. Even pausing for a few seconds allows the more rational, conscious part of your brain to kick in so you can respond in a more thoughtful, intentional way.

A few years ago, I was selected to join a very prestigious leadership development programme. This was my dream job at the time and I had wanted to be part of the programme for four years prior to applying and finally being selected. The person I was reporting to was a career educator and I felt that at times he was quite resistant, aggressive and borderline angry when I shared new ideas with him. Instead of dealing with the tension head-on, I chose to ‘ignore’ it and focus on the work. I wasn’t going to let anything or anyone get in the way of enjoying my work or having the impact I wanted to have. I chose the flight response and avoided him at all costs. When he asked me to come to his office, I would walk in and then slowly back away towards the door until we were finished speaking.

His responses to me in further incidents became more and more aggressive until it all exploded. One day, he came to my cubicle quite upset and said: ‘I know what you’re doing and I want to talk to you in my office.’ It was on like Donkey Kong. It was on and poppin’. I had pushed every affront down and now every single one of them was going to come out without my having any control over them. I can still remember the sound of my heels on the plastic runner between my cubicle and his office as I stomped over. American comedian Amanda Seales talks in one of her stand-up routines about the scale of Blackness: from Stacey Dash (a conservative American political pundit) to Nat Turner (a slave who led a group of slaves and free Black people in a four-day rebellion in 1831). In that moment, I was definitely tap-dancing all over the Nat Turner side. The gloves were off and I was prepared to be the Blackest version of myself that I had ever been. I listened quietly as he proceeded to tell me what he thought of me (for the record, none of it was positive). Once he was done, I totally unleashed (in a rather loud voice) all my suppressed anger, which was born from every instance where I felt he had been rude, aggressive, insecure and territorial towards me.

When I was finished – and I’m ashamed to admit this (sorta, kinda . . . well, not really) – he began to tear up. By the time those tears welled up in his eyes, my heart was ice cold towards him and I felt no sympathy. He apologised to me and I just walked out of his office, breathing hard and with my chest still heaving from the unmitigated rage I felt. Once I had calmed down (which took me a minute . . . okay, hours), I had to ask myself three questions: how did we get here? What part had I played? And what would I do differently to make sure I never ended up in a situation like this ever again with him or anyone else?

I didn’t have to look too far or too deep for the answers. We were here because I didn’t know one could have a calm, rational disagreement, and thus I was ill-equipped to handle conflict. I thought my two options were silence or rage. I subconsciously believed that I could be successful and have impact in spite of the dysfunctional relationship with my manager. I had chosen to suppress my emotions and feelings every time I was upset at something he said or did. I told myself that it didn’t matter how either of us felt. In other words, I had lied to myself. I tried to tell myself that the latest slight didn’t matter and that I had forgotten about it, until one day I exploded because I could no longer suppress my emotions and feelings. Sometimes it takes us a while to learn certain lessons. I knew I hadn’t handled it well. Luckily, not long after that incident, my reporting relationship was changed so I became his peer, reporting to his manager. I didn’t have to deal with him or put into practice the lessons I learnt from that situation. If I could go back in time, I would have addressed those situations where I felt he was rude or aggressive to me in a calm manner, especially if I was still upset a few days later.

Another lesson I learnt was to gather the context when you start working. I had no idea that my manager had been demoted prior to my joining. I believe he was quite insecure because of the demotion and I think the tremendous hype around my arrival only made it worse. In his mind, I was a Harvard hotshot who was coming to take his job. Had I spent time gathering the context, I would have known about the demotion and I would have couched my new ideas and suggestions slightly differently. I would have made sure that he knew that my intentions were not to usurp his job but rather to make the team (and him) look good and our output even better.

| Sometimes we are challenged in ways that might cause us to feel very emotional. But even if you’re right, when you blow up, you’re going to be wrong. It doesn’t matter what was said to you. If you get into a shouting match in the middle of the trading floor with John, a whole bunch of other people see you and they don’t know exactly what happened. All they know is that you and John are screaming at each other. Even though he instigated it, that’s not the point. You’re now guilty because you are in a professional work environment in a company that is paying you for your qualifications and education. And now you’ve tarnished your reputation because you’re volatile in their eyes.” – Artis Brown |

Mentors and sponsors

| If someone has the right mindset, you give them the benefit of the doubt and you spend the extra hours coaching them. I look at potential and mindset to determine who I mentor. If someone comes to me without me knowing the person’s potential, I will help them because they are humble and want to learn.” – Stefano Niavas |

A mentor gives you wise counsel and they share their experiences to guide you in the right direction. They motivate you, provide support and set an example. You should have mentors both inside and outside your company. External mentors can give you a perspective on the industry, how other, similar organisations work, and what you need to do to stay relevant in your industry. Your internal mentors can help you understand how your company works, but they might struggle to help you understand the industry overall if they’ve been in that same environment for a long time. Remember that you can have mentors for different topics. Maybe you also have a mentor who has a similar personal life structure as you; this person could be especially helpful to you because they help you think about how to juggle professional and personal demands. Either way, you need to be clear about why you want a mentor, what you want to get out of the relationship and what you want to give to the relationship.

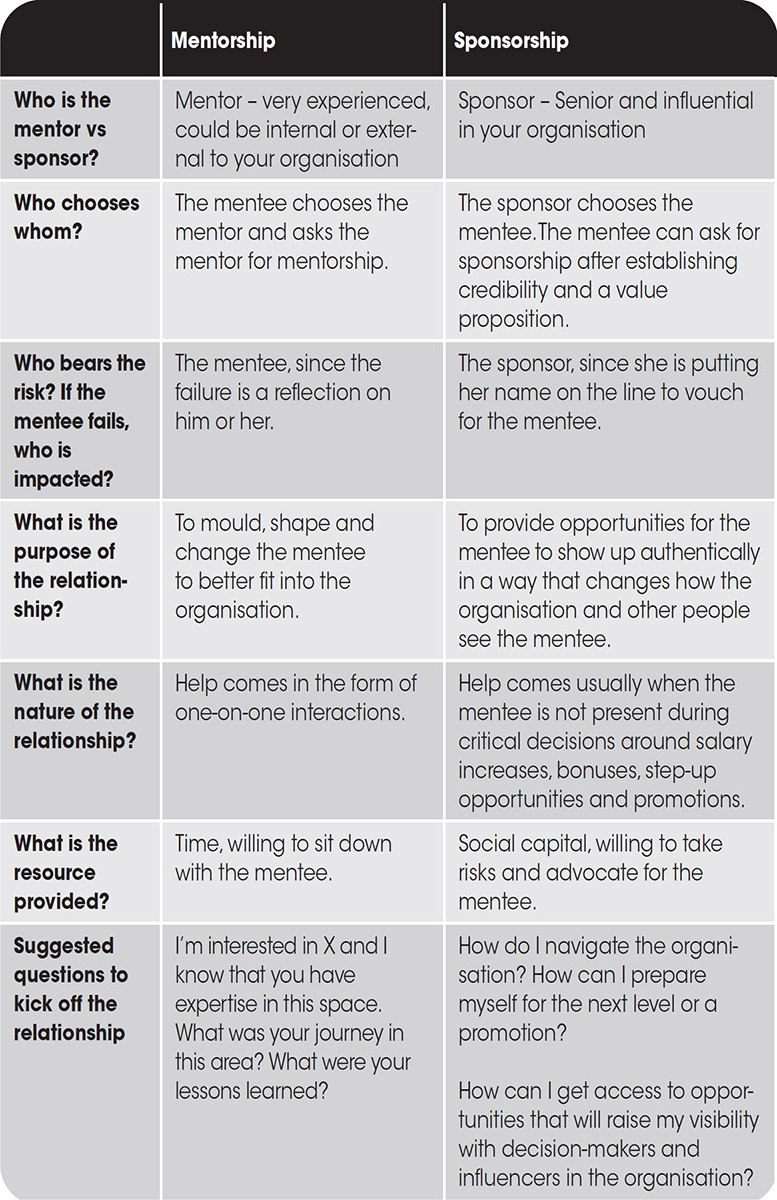

Remember that there are differences between mentors and sponsors. A sponsor is someone who works in your company who does not just have a senior title but has influence, decision-making power and a seat at the table when the decisions that affect you most are being made – decisions about promotions, developmental assignments, performance ratings and bonuses. Because you won’t be present in discussions where some of the most important decisions about your career are being made, you’ll need someone in that room advocating on your behalf.

A sponsor, specifically, needs to meet certain criteria. He or she is someone who can create opportunities and open doors for you within your organisation; otherwise, the person cannot do much to actively help you on your path. A good sponsor helps you to build your visibility and credibility. However, before you get to that point, you should have impressed him or her with your performance, because this is how you earn their support. Sponsors are earned; mentors can be requested. As soon as a sponsor has first-hand knowledge of your abilities, he or she will be willing to put their social capital and reputation on the line to back you. It’s ideal if you have multiple sponsors backing you, for two reasons: first, in case one of them leaves, you don’t have to start from scratch; and, second, it’s advantageous to have multiple people helping to build your reputation and open different doors for you.

Your relationship with your mentor or sponsor should not be a one-sided, transactional one. Find ways to add value to that person. It may not seem like you have anything to offer since this person is so much more senior to you, but you do. For example, if this person works in financial services and you see an article that might be interesting to her, send it her way. If you know that they are working on a big proposal and there is some number-crunching that needs to be done or a PowerPoint presentation that needs to be created, offer to help. And, as I’ve mentioned before, if you need help unpacking feedback you’ve received at work, ask your mentors and/or sponsors to help you interpret it. Mentors and sponsors also get a kick out of sharing their wisdom with a young, talented person, being a part of your development journey and developing the next generation of leaders. If a senior person invites you to lunch or to grab coffee, take it seriously and accept the offer. It’s unlikely that that person is offering to spend time with everyone, so he or she obviously sees something special in you. Even if he or she cancels on you five times, keep rescheduling. Capitalise on the opportunity to build that relationship.

Based on my own experience and insights from Professor Rosalind Chow of Carnegie Mellon University, I’ve created a chart that highlights the key differences between a sponsor and a mentor.

| I got an email from a young man and it said: ‘I read your profile. Would you be my mentor?’ But I wondered: what kind of relationship did he want? What was it specifically that he needed? A more effective approach is to ask specific questions. He could have said:‘I saw that you are interested in so and so. Could you please give me some insight on that?’ Mentors can speak words of correction and give you perspectives that you wouldn’t have had otherwise. I’d say to a new mentee that your mentor can learn as much from you as you do from them.” – Obenewa Amponsah |

Mentor vs Sponsor

| Everyone deserves a mentor. Mentorship is equal opportunity. Sponsorship is earned.” – HBR podcast Women at Work. |

People of colour are very familiar with the concept of a mentor, but many of us have only recently learnt about the importance of a sponsor. I would say that many of us are over-mentored and under-sponsored. If I were to choose between having a mentor and having a sponsor, I would choose a sponsor. They can bang the table for you to get that increase, promotion and/or stretch assignment that is critical to your advancement. Even though you might be at the same company with people at the same level as you, you probably are not all having the same quality of professional experience. And not all work opportunities are created equal. A friend of mine used to work in investment banking at Goldman Sachs and a lesson he taught me was that not all deals are the same. You want to make sure you’re on teams that manage deals with the best opportunities for learning, and with the most influential leaders in the office.

Your sponsor will help you gain access to premium opportunities such as these. Whereas some junior employees have to figure things out on their own, others have sponsors on their side who can give them the inside track, thus helping them to better understand and more effectively navigate the environment. If you have senior leaders who are excited about you, and who sing your praises, they can help strengthen your reputation in the eyes of other seniors. Which leaders at your company are excited about you and your potential? If no one is excited, ask yourself why. What can you do to build your credibility and a value proposition (the unique contribution that you bring to those you work with) so that leaders become excited about you?

| I was the first of my family to go into corporate America, so there wasn’t a pathway, but I knew I needed to talk to people who were senior in the organisation. Get with people who know what’s going on. I knew that I couldn’t survive this on my own; I needed to be in lockstep with someone. Always look for people who you can partner with that can coach you, mentor you and help you see around those corners. Stick to that and you’ll gain a lot more confidence.” – Tina Taylor |

If your goal is to build your network, how will you know if you’ve built your network with the right people in the right way if you’re not specific? A better way of tackling your goal is to be specific about how you want to attain it. For instance, you could frame your goal of building your network in the following way: ‘By the end of 2021, I will be able to include person X as part of my network. Person X will be able to connect me to opportunities and introduce me to other people to help me build my network further.’

Once you’ve mapped out your plan to meet and/or build a relationship with person X, you have to execute it. The first step of the plan should be to begin to cultivate that relationship. To be honest, the kinds of people that you would want to have as a mentor are usually very busy, so a vague question such as ‘Will you be my mentor?’ can be daunting for them. When you ask a busy person this question, they might think, ‘What does this mean? What kind of time commitment is involved? I’m not sure I have that kind of time. I don’t know this person that well. What are we going to talk about?’ As you can see, mentoring you can become work for them and, trust me, they already have enough on their plates.

Be specific about what you want to discuss and about the frequency of your conversations. When you approach a potential mentor for the first time, you could say the following in your message:

[Person X], I’d love to chat about three topics when you have some time. Firstly, I’m very interested in the work that you’re doing and I’d like to learn more about your journey and lessons you’ve learnt. Secondly, I would like to share with you some of the feedback I’ve been getting to better understand what I need to work on. Finally, I’d like to run by you some of the opportunities that I’ve been offered. I’d like to get your thoughts on which ones are the best fit for me if I want to do work similar to what you’re doing. Could I reach out to your assistant to set up a time to get on your calendar so that we could discuss this further?

With these few sentences, you’ve expressed an interest in this person’s background and you’ve told him or her exactly what you want to speak about. And the cherry on top: you’re asking exactly how to get on his or her calendar. You’re showing that you’re serious, so once the person agrees to meet with you, you have to make sure you follow through on your request.

| I didn’t mind taking the tough assignment, living in the most rural areas or moving multiple times. That’s when I grew the most – when I had the most difficult personal and professional growth experiences. I gained mentors and sponsors when they saw that I raised my hand to take those tough jobs. Only much later in life I realised that they were working some things behind the scenes.” – Tina Taylor |

One of the biggest lessons I’ve learnt from my corporate experience in the US and South Africa is that, as a young professional person of colour, you’re going to have to let go of the idea that you only want mentors and sponsors who look like you. In some companies, there are just not enough Black senior leaders to mentor and/or sponsor every young Black person in the organisation. At this point, the numbers just don’t add up. One Black senior leader cannot mentor 60 junior Black employees. Your options are therefore to go without, clamour for the attention of a few Black leaders or learn how to build and maintain relationships with older, senior people who will likely be male. (Sadly, women still have a way to go to level the playing field.)

At this stage, most of the people who are in power are old(er) men and many of them are not comfortable with, nor accustomed to, trying to find commonality or build relationships with people of a different (younger) generation, ethnicity or gender. As much as we would like our leaders to reach out to us and make us feel at home, some of them just don’t have the capacity to do so. And, trust me, you need them more than they need you, so you’re going to have to be the one to extend and keep on extending yourself.

| The minute I walked in there as a market analyst, the African-American VP grabbed me. He said, ‘Kapungu, we’re having lunch every week.’ He basically forced this on me. He saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself. You need someone to believe in you even more than you believe in yourself. They push you to do more than you thought you could. They create opportunities for you. I would not have been able to get sponsored to attend Harvard Business School, get the support to move to Africa or have many of the opportunities that I’ve had had it not been for those people in my life.” – Fungayi Kapungu, Chief Financial Officer, Infinite Foods |

Even if you work in an environment where everyone looks like you, or comes from the same cultural or ethnic background as you, you will still have to work hard to connect, build and maintain relationships with people who differ from you. They will likely be older than you, might have different ideas about work and think differently from you. While all these differences add richness and colour to the work environment, they can also be a source of tension and judgment, so we have to work extra hard to connect and find commonality in the midst of these differences. The ultimate goal is for you to learn to appreciate and fully leverage these differences in order to have greater impact and better serve your customer or client.

Remember, your relationship with your mentor and/or sponsor is not an equal one: you need them more than they need you. So if your intention is to learn, grow and cultivate supporters among the seniors in your company, you need to understand that knowledge, mentorship and sponsorship can come from people who don’t look like you. Might it be uncomfortable? Yes. Might it take a bit more work to find common ground? Probably. Will it be hard at first? Yes. Does it have to be done? Absolutely. When I reflect on my career, the majority of people who have created opportunities for me have been people who are different from me – either of a different ethnicity or gender or both.

An example of when I had to put this principle into practice was during my second stint at Deloitte. At the time, I was not performing as well as I had hoped. I had gotten quite rusty while I was away at business school, especially in terms of managing stress and dealing with demanding clients. The head of my department decided to assign me a mentor: Eileen, a senior executive in the same consulting group as me. I wondered what I could possibly have in common with her. She was white and at least 20 years older than me, if not more. Plus, I assumed that, because she was in a senior position, she had had a pretty straight trajectory to the top. How was she going to understand the challenges I was facing?

Prior to our first session, I had to answer a list of questions about my life and was told to bring them along. Little did I know that Eileen also had to answer the same list of questions. When I arrived at the session, I was quite nervous, but as she started to share some of her own – very personal – failures and mistakes, I realised that we are all human beings underneath the titles, big salaries and physical characteristics. We are all just trying to successfully navigate a very complicated world. Her transparency encouraged me to open up and I instantly sensed that I could trust her. This experience taught me that everyone has a story that I can learn from and that no one has had a straight, obstacle-free path to the top. I also learnt that in being vulnerable as a leader – when you remove the leader mask – you become much more relatable to those you lead. I filed this away as a key leadership trait that I wanted to emulate and an exercise that I would do with my mentees and direct reports at some point.

| I looked for mentors who looked like me and had similar experiences to mine. Because I couldn’t find them, I stopped looking. I found different mentors for different reasons – Black women entrepreneurs, white males in tech. Find mentors who are looking out for your personal best interests.” – Aisha Pandor, CEO, SweepSouth |

If you reflect on your personal relationships, they began with your getting to know other people. Where are you from? Where did you grow up? What do you care most about? What do you value? What was your professional journey? What are some of the most valuable lessons that you have learnt during the course of your career? Just as we spend time getting to know people, their stories and their family make-up, we need to spend time doing the same thing at work. When you’ve established a good relationship with a mentor or sponsor, make sure you pay it forward as soon as you can. If you’ve been at a company for six months, you know more than the person who just started yesterday. Make sure you offer what you know and any tips and tricks that can make that person’s transition into your organisation smoother.

The connection between EQ and your relationships

| You might have a colleague that you’re not getting along with and you could go in and be the mad Black woman or the mad Black guy and take them on. But you have to choose how to navigate these situations and how to navigate people; you have to be comfortable with the potential outcome or knock-on effects. To me, it’s like mind chess: you have to know how to navigate that over time. Know the different pieces on the chessboard, who’s who in a room and who has allegiances and connections. Really reading and understanding but also being honest about yourself.” – Ronald Tamale |

One of the greatest tools in building strong relationships is emotional intelligence, or EQ. EQ, a term coined by Peter Salovey and John D Mayer, is defined as the ability, first, to acknowledge, interpret and regulate our own emotions, and, second, to acknowledge, interpret and persuade the emotions of others. To understand EQ, we need to understand what emotions are. We can say that they are conscious mental reactions (such as anger or fear) that we experience subjectively as strong feelings. These feelings are usually directed toward a specific person or situation and typically accompanied by physiological and behavioural changes in the body.

In my experience of coaching individuals, I saw that people sometimes have difficulty in identifying emotions. This stems from the fact that they intellectualise and/or judge what they are feeling, as opposed to merely identifying the feeling. People might also struggle with their emotions because they’re focused on not showing perceived weakness or vulnerability, which might result from their expressing their emotions. In other cases, people might lack the vocabulary to express themselves or might never have been given the permission to have and/or express their feelings.

Emotions should never be judged as either bad or good. They just are. However, we do not have to allow our emotions to rule over us. We can choose how we want to express what we feel. Emotions are merely signals that show us that something is out of balance or needs to be delved into more deeply. When you feel overwhelmed by a particular emotion, always ask yourself: what is this feeling trying to tell me? Maybe the anger that you are experiencing is telling you that you have some unresolved hurt that you need to work through. Maybe the relaxation that you are feeling about a recent decision indicates that you made the right choice.

| Many people don’t appreciate what emotional energy they’re exuding. They don’t know the vibe that they’re bringing unless they’re conscious of it. You bring that energy in the way you talk to people. You bring that energy in the way you look at people, your body language, a lot of things. And it can impact your decisionmaking.” – Artis Brown |

In many Black families, the focus is on merely surviving and moving on with life. We do not create the space to spend time on, or to investigate, emotions and trauma. Historically (and even still today) in Black culture, we have not been comfortable talking about mental health. Many of us have not had widespread access to, or even trust in, mental health professionals to help us understand, process or give voice and language to our emotions. If we are ever to fully master ourselves, I believe, we have to be able to know what is going on within us. We have to be able to own and interrogate what we’re feeling so that we can intentionally choose how we want to respond to those emotions. When we don’t, we run the risk of unleashing those negative emotions onto other people. If we want to understand others, we need to understand ourselves first.

A great way to get to the root of your feelings is to close your eyes, speak from your heart and say the following: ‘I feel [fill in the blank]’ or ‘I felt [fill in the blank].’ You could feel angry, sad, anxious, hurt, embarrassed or happy; try to use one of the words (or even a variation of them) to express how you feel at heart. If you are unable to recognise and understand your feelings, it will be very difficult for you to manage them. You’ll also find it very hard to recognise, understand and influence others’ feelings. One of the most important skills I have cultivated – and which has helped me develop my EQ – is sitting with my emotions and understanding their roots.

The famous American academic and author Brené Brown talks about how we are better at offloading our emotions onto other people than at sitting with them ourselves. If we feel isolated or sad, she says, we yell at or are brusque with others, instead of dealing with those emotions ourselves. In the workplace, this is not the type of team member you want to be, and neither is this the type of person you want on your team. You definitely do not want to be on the receiving end of a team member’s emotional offloading, and you wouldn’t want anyone to be on the receiving end of yours either.

Offloading creates tension, insecurity and a general sense of unpredictability in a team, all of which undermine trust, which is the first building block of any relationship. Consider the following: how can you trust someone if you never know when he’s going to snap? How can you trust someone if you never know which version of that person you’re going to get? The same is true of ourselves. If we’re aware of how we feel, however, we can deal with it or ask the people in our lives for help by letting them know that we’re feeling a certain way. Or, if they notice a certain change in our mood or behaviour, they might be assured that it has nothing to do with them.

| It’s about cultivating maturity. It’s about being honest about your emotions, but also about being able to deal with them for what they are and not to let them define you, your actions or situations.” – Obenewa Amponsah |

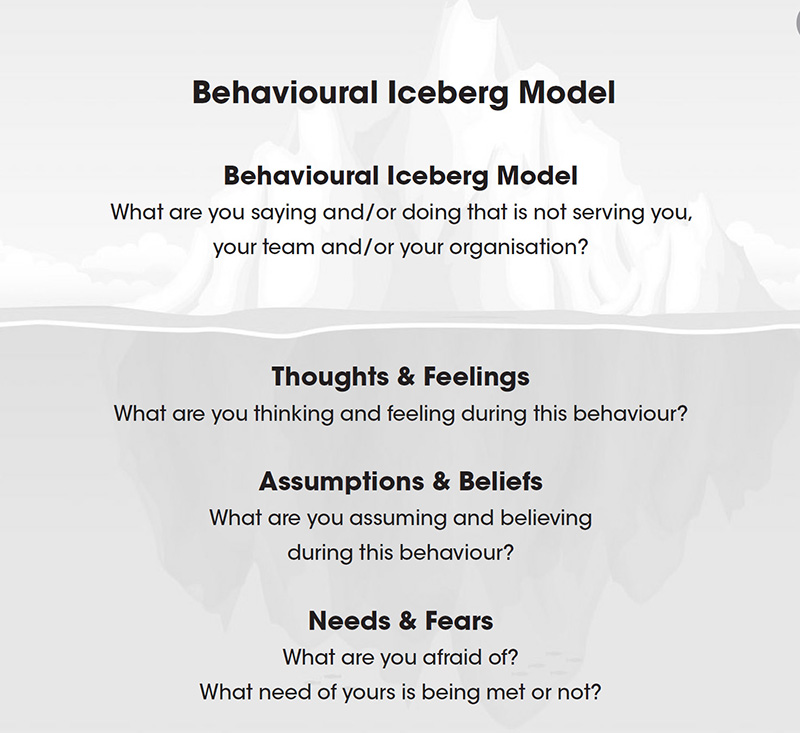

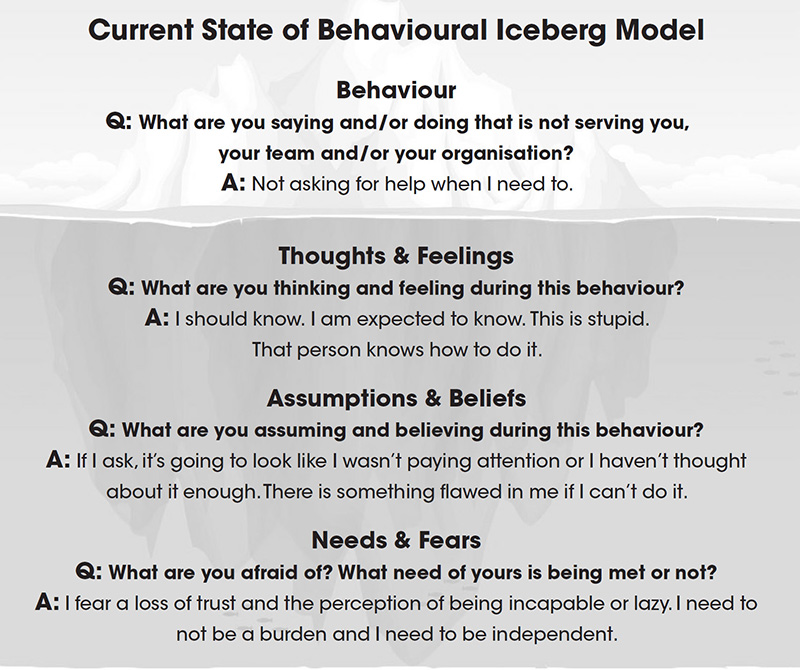

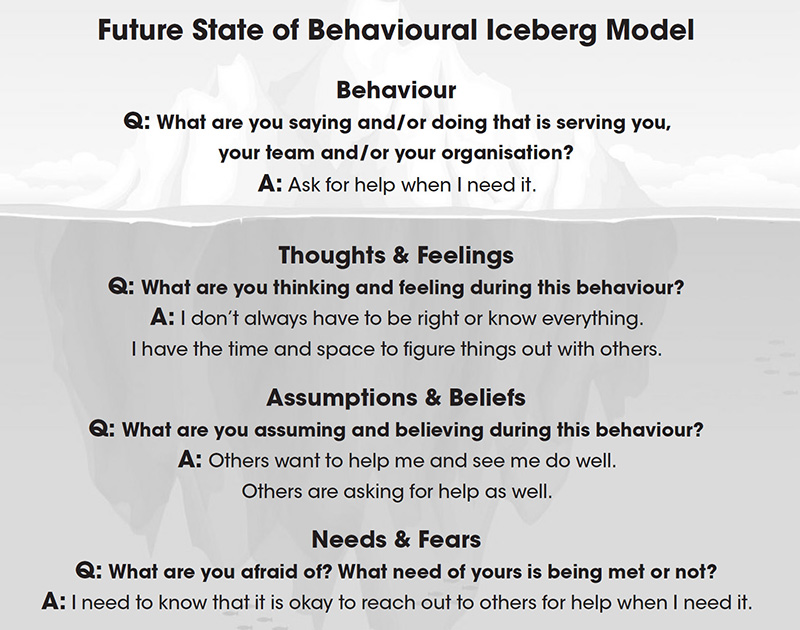

When you’re able to identify a certain emotion in yourself, your next step would be to ask yourself if the situation that triggered those emotions really unfolded in the way that you perceived it. You could learn how to understand, work through and manage your emotions by thinking through the following: could you have attached meaning to someone’s behaviour or words that the person didn’t intend? Did you make assumptions, which then triggered you to feel a certain way because you treated those assumptions as facts? Are there certain situations, comments or types of people that trigger certain emotions within you? Once you identify those patterns within yourself, you can begin to examine the root of those emotions. You might be stuck in a particular mindset, or you might be framing a situation in a particular way, which causes you to feel triggered.

The process of unpacking your emotions and understanding yourself is a lifelong, layered one. This is because different personal and professional situations with specific circumstances and types of personalities trigger us in new ways. As you begin to work through your own emotional identification, assessment and management, you will become more skilled at seeing what is going on with yourself and with other people, thus building and strengthening your EQ. You will not necessarily be able to label others’ emotions or the root causes behind them, but you will be more emotionally attuned. You will then be able to help other people take a step back to identify and understand their emotions too.

| For smart people, logic and sound arguments tend to be the default for making a point. Leaders need the ability to make sound arguments, but it takes more than that to influence others. As your leadership develops, you’ll realise that you aren’t just managing people; you are managing people’s emotions. You aren’t just managing their work; you’re managing how they feel about their work. Sometimes you can use logic, sometimes you can’t. If your default stays at logic, you will stumble at least half the time.” – Chaka Booker, Managing Director, The Broad Center and Forbes.com columnist |

We have to understand who we are – the good, the bad and the ugly. Remember that the importance of understanding yourself is not just for your own benefit: it also benefits the people who will work on teams with you and follow you in the future. Your preparation to be a great leader of others starts with being a great leader of self. You lead from who you actually are, not who you want to be. The more you know yourself, the better, more authentic and more mature a leader you will be in the future. You will know what your strengths are and thus your true sources of distinctiveness. This self-knowledge will give you the confidence to voice your opinions and firmly position yourself at the table where decisions are made.

You have a sense of self and self-confidence that the world can’t touch. You know who you are and you stand firmly in your power. Conversely, you also know what your areas of development are, which helps you understand who you need around you, both to complement you and to provide those skills or perspectives that you lack. Knowing your own limitations helps you to remain humble because you know that you don’t bring everything to the table. It helps you to be open and sometimes to defer to the opinions, perspectives and ideas of others. Understanding your emotional triggers helps you to know what types of situation might upset you so that you can try to either reduce or eliminate the chances of being in those situations. Additionally, you can develop techniques to help manage negative emotions or you can work on changing your perspective so that those situations and people no longer elicit the same emotions in you. Harvard Business School professor and former Medtronic CEO Bill George says that ‘the hardest person you will ever have to lead is yourself’, and you are the only person you can control. How can you expect people who report to you to be mature if you are immature? How can you expect them to respond in a professional, calm way if you don’t? Being able to lead by example starts with examining who you are, what your personal and professional goals are and what might get in the way of your being and doing all that you want to be and do. The type of leader of others that you will be begins with the type of follower that you are now.