Chapter 8. Legal Issues

This chapter deals with the legal aspects of defending against DDoS attacks, or pursuing criminal or civil remedies against perpetrators of DDoS attacks. It provides a cursory overview of the subject, and is by no means intended to provide legal advice. It is based on current law existing in the United States; thus, readers in other countries will need to consult their local laws for further guidance.

Because of differences among jurisdictions, especially among countries, all readers are encouraged to consult with a qualified attorney to obtain specific advice regarding situation- and jurisdiction-specific legal options. (All dollar amounts shown are in U.S. dollars.)

That said, the reader can learn much about the practicalities of using the legal system in response to DDoS attacks by examining how the legal system generally functions; the basic processes of discovery, investigation, and prosecution; and civil litigation. Since this process is complex and deliberate, the rate at which a case moves through it can vary depending on how well prepared a party is beforehand. Knowing what to expect and some of the proper things to do may improve the party’s chances of obtaining a favorable outcome.

8.1 Basics of the U.S. Legal System

Before addressing some of the steps to follow in initiating legal proceedings, it is helpful to understand the pathways through the U.S. legal system. Many other legal systems throughout the world are similar, but laws can and do vary significantly, even within similar systems.

There are fundamentally two distinct types of law: criminal law and civil law. Depending on the circumstances of a DDoS attack, criminal and/or civil actions may be brought.

A criminal action is brought by the government against an individual for violation of criminal statutes, but only after that individual has been charged with violation of such a statute. The types of criminal acts associated with DDoS attacks fall into two categories—misdemeanor or felony, depending on the gravity of the crime. Criminal actions can be brought at the state or federal level depending on whether state or federal laws have been violated, and the location of the parties involved. Essentially, in order for the government’s attorney to have a successful prosecution of a defendant, the state must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed the crime or crimes alleged by the government. Penalties may include monetary fines, imprisonment, or both.

Civil actions are the result of disputes between individuals for which a legal remedy may exist. These are typically matters such as breach of a contractual agreement, or breach of a duty imposed by law. In the case of DDoS attacks, causes of action may include negligently failing to secure computers used to attack someone, or negligent interference with commercial activity. There are four requirements for a suit charging negligence: (1) The injured party, the plaintiff, must show that a duty was owed by the defendant to do or not do something; (2) the plaintiff must show that the duty was breached by the defendant; (3) the plaintiff must also show that the defendant was the cause of the harm to the plaintiff; and (4) the plaintiff must have been harmed in such a way that damages may be awarded.

In a civil suit, the plaintiff (the party bringing the suit against the defendant) must prove, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the defendant is responsible for the plaintiff’s injury. The court then determines an appropriate remedy, which can include the assessment of monetary damages or directing a party to perform (or refrain from performing) some action. This is known as a suit in tort (as opposed to a suit in contract).

A special type of civil action that may apply in DDoS attacks is a class action suit. A class action is usually an action brought by a representative plaintiff against a defendant or defendants on behalf of a class of plaintiffs who have the same interest in the litigation as their representative and whose rights can be more efficiently determined as a group than in a series of individual suits. In recent years, several high-profile class action suits have been brought by consumers in the United States; thus, readers may be familiar with the lawsuits brought by victims of asbestos poisoning, tobacco addiction, leaky silicone breast implants, and a particular type of intrauterine birth control device.

Since criminal actions are the responsibility of the government, a victim should report suspected crimes to the appropriate authorities1 and provide them with sufficient evidence of the alleged acts and the harm caused by those acts. Such evidence will allow the government’s attorney to determine applicable laws and whether or not to proceed with prosecution. In order to assess the likelihood of obtaining a successful prosecution, the authorities need to know things such as the location of the victim, the type and monetary amount of damage suffered, etc.

It also helps to have evidence that can lead to the identity of a suspect. This is important for two reasons.

First, victims should be prepared to at least gather some samples of network attack traffic and other log information that confirms that an attack is actually taking place. It is not uncommon for a victim who suspects he is under attack, and may even believe he “knows who is attacking and why,” to later learn from a consultant that the problem is actually a bug in a Web application, insufficient resources on a server, or a misconfiguration of hardware or software. It is advisable to first perform some level of capture and analysis of network traffic and server logs before contacting the authorities.

Second, both civil and criminal actions require that an individual, or group, be identified and brought into the legal process. You cannot sue, and the police cannot jail, an unknown entity. In the case of many DDoS attacks, the complexity of the “crime scene” may prevent a direct identification of a suspect. Even if a suspect can be identified, he may reside in another country, and it may be difficult, if not impossible, to bring him before the presiding judicial authority. Extradition may be an option in certain criminal cases, but not for civil actions. Furthermore, the United States does not have an extradition treaty with every foreign government. Thus, this option may not be available in every case in which the culprit is a citizen or resident of a foreign country.

8.2 Laws That May Apply to DDoS Attacks

On the criminal side, the primary federal law that applies to most DDoS-related attacks is the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, or 18 U.S.C. §1030.2

An example of this law being applied to DoS attacks is the case of United States v. Dennis in the District of Alaska in 2001 [ws]. In 2001, a former computer systems administrator in Alaska pled guilty to one misdemeanor count for launching three e-mail based DoS attacks against a server at the U.S. District Court in New York. He was charged under 18 U.S.C. §1030(a)(5) with “interfering with a government-owned communications system.”

Other DDoS-related attacks mentioned elsewhere in this book, such as the extortion attempts against online gambling sites and online business, may fall under 18 U.S.C. §1030(a)(7), which covers extortionate threats. Analysis of a Congressional Research Service report [fra] suggests such attacks may also violate

• 18 U.S.C. §1951 (extortion that affects commerce)

• 18 U.S.C. §875 (threats transmitted in interstate commerce)

• 18 U.S.C. §876 (mailing threatening communications)

• 18 U.S.C. §877 (mailing threatening communication from a foreign country)

• 18 U.S.C. §880 (receipt of the proceeds of extortion)

The act of breaking into hundreds or thousands of computers to install DDoS handlers and agents may violate 18 U.S.C. §1030(a)(3) (trespassing in a government computer). If a sniffer is used to obtain passwords as part of this activity, the attacker may have violated 18 U.S.C. §1030(a)(6) (trafficking in passwords for a government owned computer) or 18 U.S.C. §2510 (wiretap statute).

Even an attempt to violate any of the sections of 18 U.S.C. §1030 listed above is itself a violation of 18 U.S.C. §1030(b).

On the civil side, 18 U.S.C. §1030(g) creates a civil cause of action for violation of subsection (a)(5)(B), which includes any of the following:

1. Loss to one or more persons during any one-year period (and, for purposes of an investigation, prosecution, or other proceeding brought by the United States only, loss resulting from a related course of conduct affecting one or more other protected computers) aggregating at least $5,000 in value.

2. The modification or impairment, or potential modification or impairment, of the medical examination, diagnosis, treatment, or care of one or more individuals.

3. Physical injury to any person.

4. A threat to public health or safety.

5. Damage affecting a computer system used by or for a government entity in furtherance of the administration of justice, national defense, or national security.

Damages include only economic damages, and the civil action must be brought within two years of the act or when the damage was discovered.

Another civil action surrounding a DDoS attack against a business, which prevents customers from engaging in business with the victim and thus damages its business, would be “Tortious Interference with Business Relationship or Expectancy.” To prove this, the plaintiff (the DDoS victim) would have to show several things, including such elements as knowledge of the business relationship between the victim and its customers, knowledge that the action (the DDoS attack) would disrupt this relationship, knowledge that the result would cause damage to the victim, proof that the defendant caused such disruption and damage, and proof that the victim has suffered a loss. (Here is where careful evidence collection and realistic incident cost estimation become very important.)

The Department of Justice Cybercrime Web site [fra] also lists these laws as applying to computer intrusion cases:

• 18 U.S.C. §1029 (fraud and related activity in connection with access devices)

• 18 U.S.C. §1362 (communication lines, stations, or systems)

• 18 U.S.C. §2510 et seq. (wire and electronic communications interception and interception of oral communications)

• 18 U.S.C. §2701 et seq. (stored wire and electronic communications and transactional records access)

• 18 U.S.C. §3121 et seq. (recording of dialing, routing, addressing, and signaling information)

This is a representative, yet not exhaustive, list of laws that may apply. Readers are urged to consult with an attorney and local/federal law enforcement agencies in their jurisdiction in order to learn more about what legal options exist in the event of a DDoS attack, and how to prepare to exercise these options when and if a DDoS attack occurs. It is also important to understand your responsibilities and potential liabilities in the event that your own systems are taken over and used to attack someone else, in which case you may be the defendant, not the plaintiff, in a civil suit.

8.3 Who Are the Victims of DDoS?

If we start with the premise that DDoS attacks are actually two-phased attacks—first breaking into thousands of computers and installing malware on them to use for attacking, and then using them to wage one or more DDoS attacks—then it follows that a significant amount of damage is actually spread out over a very large number of sites, in many jurisdictions, and over an extended time period. And that is before any DDoS flooding even takes place. Arguably, there may be more damage in aggregate from the cleanup of all the DDoS handlers and agents than is suffered by smaller DDoS victims, but there have certainly been DDoS attacks against large sites with high income from advertisers who may suffer multimillion-dollar losses from attacks that last only a few hours to a few days.

Not only are damages spread out, but so is the evidence necessary to attribute the attack to a specific individual or group and pursue criminal prosecution or civil remedies. As described in Chapters 5 and 7, traceback can be difficult, if not practically impossible. The network traffic associated with the attack that proves what tool was used, how the DDoS network was controlled, and who did it, is spread out and highly volatile. Once the DDoS network ceases to function, there is no more network traffic—nothing left to capture.

The quality of incident response by all parties involved can and does affect the overall investigation, yet the distributed nature of DDoS attacks may mean that these parties are in different countries, with different languages, time zones, and entirely different legal systems. Victims whose systems were used as handlers and agents may simply “wipe and reinstall” the operating system and applications, destroying evidence in the process. Network providers at those sites, or the DDoS flooding victim site, may not focus at all on capturing network traffic, instead only acting to stabilize the network. In doing this, they fail to capture highly important evidence at the only time it may be present. In cases of extortion, it may be easier to follow the money than to follow the packets. (This is touched on by Lipson [Lip02].)

In the past few years, victims of the second phase of DDoS attacks (the flooding) have included:

• Internet Relay Chat (IRC) networks.

• Web sites associated with government agencies, such as the NSA, FBI, NASA, Department of Justice, and the Port of Houston in Texas.

• Web sites associated with news organizations, such as Al-Jazeera, CNN, and the New York Times.

• Terrorist-related Web sites.

• Web sites associated with opposing sides in political conflicts (e.g., Arab/Israeli, Indian/Pakistani, U.S./China).

• Web hosting sites, such as Rackspace.com and Rackshack.com.

• Online gambling or pornography sites.

• Anti-spam sites.

• Major telecommunication providers or ISPs, such as British Telecom, Telstra, and iHug.

• Major online businesses, such as Microsoft, Amazon, eBay, SCO, and Akamai.

The motivations for DDoS attacks are varied, including: simple pranks; grudges for perceived personal slights or denigration; making a political statement; exhibiting rage; for personal aggrandizement within peer groups; attempting to gain financial advantage in betting or auction scenarios; extorting money.

It is not easy to generalize about why someone would be attacked, but it is usually not hard to find reasons why someone may wish to bring harm to your organization. It then takes only sufficient technical skill, or the ability to engage (perhaps by hiring) someone who does have these skills. It is believed by many that it is only a matter of time before a terrorist organization or nation-state actor will use DDoS attacks for some political or military objective, perhaps directing the attacks against the critical infrastructures that support the United States economy. It would be unwise to believe that your site is entirely immune from being attacked, and this possibility should be weighed appropriately in your risk assessment, your continuity of operations policies and procedures, and your insurance portfolio.

8.4 How Often Is Legal Assistance Sought in DDoS Cases?

Each year, the FBI and Computer Security Institute (CSI) do a survey of security professionals in government and corporate environments. The 2004 survey is described in Appendix C (Section C.1). The key finding to note in this year’s survey was that the 269 reporting institutions calculated total reported costs from DoS attacks of $26,064,050. DoS is the most costly kind of cyberattack this year, nearly twice as costly as the next largest category, theft of proprietary information (at $11,460,000 in losses).

The author of an article introducing the 2003 survey [McC03] makes an interesting statement regarding investigation of such crimes:

The FBI generally has a trigger point of $5,000 for a cybercrime it will pursue. Given the number of incidents and the limited number of agent-hours that can be devoted to cybercrimes, this is certainly understandable. However, it is important to remember that Cliff Stoll’s famous investigation detailed in The Cuckoo’s Egg (1989) [Sto89], which turned up major holes in the highly sensitive Mitre Corp.’s phone system and ended up uncovering a spy, began with a discrepancy of only a few pennies.

Obviously, the initial monetary loss should not be the sole factor that determines whether authorities decide to investigate a particular cybercrime. Unfortunately, I can’t think of any other criteria that could be applied to better effect. So for the foreseeable future, companies will probably have to rely on internal resources to investigate most computer crimes. Outsourcing may be possible, but that would require companies to divulge sensitive data to outsiders, and in any case, there just aren’t that many trained cybersnoops available.

A report on the British Computer Misuse Act (CMA) by the “All Party Internet Group” [api04] (both described in more detail in Section 8.10) also covers the topic of the viability of prosecution of DoS attacks. In paragraphs #59 and #60 their report states,

We received written and oral evidence from [the Association of Remote Gambling Operators, new trade body for online bookmakers] about the criminal DDoS attacks that are currently being made on gambling websites both in the UK and elsewhere. These attacks are accompanied by monetary demands (for amounts between $10,000 and $40,000) to make the attacks stop. ARGO told us that their members would not give in to this blackmail, but that the impact on the gambling businesses had been very severe indeed. The National Hi-Tech Crime Unit (NHTCU) has become involved in the investigation, but the perpetrators are believed to be based abroad, which sets some limits upon what they are able to quickly achieve.

Almost every respondent from industry told us that the CMA is not adequate for dealing with DoS and DDoS attacks, though very few gave any detailed analysis of why they believed this to be so. We understand that this widespread opinion is based on some 2002 advice by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) that s3 [subsection 3] might not stretch to including all DoS activity. Energis and ISPA told us that they knew of DoS attacks that were not investigated because “no crime could be framed.”

Taking a look at another source of data, based on the numbers of incidents detected by groups such as CAIDA and Arbor Networks, it is probably safe to say that a very, very small percentage of the thousands of actual attacks per week ever result in legal action (either criminal or civil). Since a very large proportion of the attacks that occur on a regular basis are directed at IRC networks and their users—IRC being a free service, meaning no concrete monetary losses associated with the DDoS flooding—it follows that the actual damages from the majority of DDoS floods are also low. It is very unlikely that, even if reported, the FBI would expend scarce resources to investigate these attacks. Reporting would, seemingly, do very little good.

Of course, there are victims of DDoS flooding attacks who lose access to not only their servers, but sometimes their entire network and parts of their upstream provider’s network (which may spill over to other customers of that same provider). In these cases, there may be significant financial losses, and these losses may be spread across multiple primary and collateral victims. (For example, the incident involving the Port of Houston was the by-product of an attack on a third party using the port’s computers, which disrupted ship movement and may have financially impacted those shippers and even the shippers’ customers!) Worse yet, consider situations in which irreparable loss is suffered as a result of an attack (for example, loss of data from instrumentation, say on scientific experiments at remote locations) or loss of life.

These are all, however, the second-phase victims of DDoS attacks. When you look at the first phase of DDoS attacks, in which thousands of computers are compromised, the damages could potentially really add up and are, for the most part, “hidden” costs.

Let us take a look at a simple example of the two phases of a DDoS attack. Imagine that an individual breaks into 1,000 computers to create a DDoS botnet. (A thousand hosts is a relatively small botnet these days. A large botnet would be in the hundreds of thousands.) The attacker then uses this DDoS botnet to attack a small business that sells consumer electronics products exclusively through their Internet Web site. During the attack, which we will imagine lasts six days, the victim would have made $500 in net revenue per day.

The obvious loss here is to the DDoS victim, who has suffered a net revenue loss of $3,000. Depending on overhead, cash on hand, and time of year, this loss could be significant to this victim. For example, is this the last week before Christmas when this single week accounts for 20% of yearly revenue? Add on top of that the cost of dealing with the attack itself, which can add up rapidly (especially if handled by a consultant, who may charge well over $100 per hour).

For simplicity, let us say the compromised computers that were used in the attack are all owned by broadband customers running Windows XP, and assume that all of them learn that their computers have been compromised and all of them want to clean up their problem. Each of these 1,000 users takes her computer in to a local computer service company, which charges $100 to back up the computer’s hard drive, wipe the drive, reinstall Windows XP and all its current patches, reinstall all the users’ applications, and restore the data files. The individual damage to each user is $100 plus her wasted time and loss of use of her computer, but added up we have a real financial cost of $100,000 (well above the $5,000 limit for prosecution). If these were business computers, the loss would instead be lost wages for the person who cleans up the system, plus some amount of lost productivity of the user of the computer. Adding in benefits and overhead, it could be several times this $100-per-system figure.

Any of these victims could report this problem to law enforcement, but the vast majority typically will not. There are perhaps two similar situations that exist. One is the most prolific graffiti tagging, which causes similar small amounts of actual monetary losses due to damage, spread over a large area. (Even then, it is rare that a tagger can tag tens of thousands of locations around the globe.) Another is spam, where the spammer consumes the resources of many sites around the Internet for sending or relaying the spam messages.

If the preceding victims decided to report the problem, and if they were able to adequately preserve evidence and provide useful reports to the FBI or Secret Service, these federal agencies would be in a better position to efficiently and effectively investigate and prosecute a larger number of cases and thus obtain the deterrent effect that laws and law enforcement are supposed to provide. Making it easier for victims to do the right thing and encouraging them to regularly report computer crimes are keys to improving this situation.

Besides the amount of damages, there are other factors that cause many businesses’ reluctance to report computer crimes. Many corporate victims want to avoid any negative publicity for fear that they will lose their customers’ trust, that their competitors will use information about an incident to their advantage, and that shareholders or others may bring lawsuits against the corporation or its executives. Some corporate executives are also not convinced that law enforcement either understands the needs of businesses (e.g., fearing that they may come in and seize critical systems) or that law enforcement is capable enough to help.

Also, some victims do not care very much about involving law enforcement. If the attack stops, they are satisfied. At most, they may investigate purchasing defenses to help in the event of future attacks. That’s probably most true of relatively small businesses. There is an overhead cost associated with dealing with law enforcement on any issue, and many businesses may consider that overhead more expensive than the attack, or at least an added cost to the attack that they cannot afford to bear. They may also have what they believe to be sufficient insurance coverage and are satisfied with making a claim, or they may simply wish to assume any remaining risk above and beyond their existing insurance coverage.

8.5 Initiating Legal Proceedings as a Victim of DDoS

If your network and/or security operations staff can confirm that an attack is under way and that your systems have been impacted enough to cause monetary and/or physical damage, it is time to decide how to move forward. It is assumed here that your own staff, and that of your upstream network provider(s), have already identified and attempted to use all available technical measures to mitigate the attack, and that these efforts have not been adequate to bring the network back to reliable functioning.

At this point, management is faced with a decision as to whether or not to start legal proceedings.

8.5.1 Civil Proceedings

Discussed in this chapter are several theories of tort that could be used, but a victim will immediately be faced with two problems.

First, who are you going to sue? Trying to identify the perpetrator of a DDoS attack by direct traceback will be almost impossible. He may be foolish enough to brag on an IRC channel about his attack or may even contact you directly (he would have to contact you if this were an extortion attempt). However, actually identifying a physical person sitting at a keyboard and proving that he caused the damage will be very, very difficult.

Second, there is no obvious case law surrounding use of civil litigation against DDoS attackers, or even downstream liability for that matter. This may change over time, but at present this will be a hard path to follow.

8.5.2 Criminal Proceedings

Criminal proceedings are easier to initiate, but they, too, suffer the same problem of identifying the attacker. At least with a criminal investigation, law enforcement has powers of subpoenas, search warrants, and seizure of evidence to help identify the attacker, provided they have the resources and desire to pursue the case. As mentioned before, how well victims preserve, process, and present the evidence will have an impact on law enforcement’s ability to pursue the case.

Start now, before an attack occurs, by reviewing the guidance provided on the Department of Justice’s Cybercrime Web page (http://www.cybercrime.gov/reporting.htm). In case you did not read this in advance and are currently under attack, the numbers to call for reporting computer crimes at the time of publication of this book are +1-202-323-3205 for the National Infrastructure Protection Center (NIPC) Watch Desk, and +1-202-406-5850 for the U.S. Secret Service’s Electronic Crimes Branch.

You should also consider reporting the incident to the CERT Coordination Center. The CERT Coordination Center is a trusted third party, who will not release any information about a victim site, the attack, etc., without the victim’s express permission. Reporting to both federal law enforcement and the CERT Coordination Center also provides valuable visibility at a national level of potential large-scale cyberattacks or attacks targeted at specific critical infrastructure sectors, such as banking, telecommunications, energy, etc. The CERT Coordination Center can be contacted at [email protected] or +1-412-268-7090.

Organizations may also have other reporting requirements. For example, if your organization is in the financial sector, you may be required to file a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) with the Securities and Exchange Commission [sar]. Even if you are not in the financial sector, you may wish to consult this same reference and use the SAR as a model for collecting information and constructing a narrative with which to report the incident to federal law enforcement.

8.6 Evidence Collection and Incident Response Procedures

Chapter 6 goes into some detail on the type of network- and/or host-related information to gather when investigating a DDoS attack. Other references cover the topic of evidence collection, chain of custody, investigation of computer crime, and digital forensics [CERd, NIoJa, NIoJb, oECFL, Uni, IAA, oJb, CIPS, oJa].

The important things to keep in mind when collecting information that may be used as evidence are:

• Volatility of evidence. Evidence has a life cycle which dictates how long it lives, and therefore how quickly you must move to preserve it. Put another way, the order in which you collect your evidence should be arranged so as not to disturb other evidence and change attributes, such as file time stamps, or outright destroy it, for example, by overwriting disk space. See RFC 3227 for more information [BK01].

• Chain of custody. Maintaining a record of who collected the information, when, and how, and then keeping track of all subsequent handoffs of the information to others is called the chain of custody. This includes integrity checks, such as cryptographically strong hash values (e.g., SHA1 or better), which provide a unique signature of the contents. (Even better is a cryptographic time stamp of the file, which not only proves the fingerprint of the file, but also the time at which that fingerprint was made.) If it cannot be proved in court that this chain was maintained, an argument can be made that the evidence may have been tampered with, was accidentally modified from booting the system, or is incomplete.

• Records kept as a normal course of business. Logs and other records showing access and the like should be kept as a normal course of business in order to be admissible as evidence. You will be better off when these records are required for use in court if you have a standard practice that involves their collection.

See section V in the Department of Justice document “Searching and Seizing Computers and Obtaining Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations” [CIPS] for more information about evidence in computer crime cases.

8.7 Estimating Damages

So how exactly does a victim calculate losses? Even though computer crime cases go back decades, there was little firm guidance from state or federal legislatures in the United States on how to calculate damages from computer security incidents, let alone a definition of what “losses” were in these cases. This led to a great deal of confusion, and situations in which widespread intrusions involving dozens of sites were not investigated, because no single victim was willing or able to show a loss that exceeded the $5,000 limit necessary to trigger federal statutes, such as the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) (18 U.S.C. §1030).

Under the original CFAA, it was unclear whether damages could be aggregated. This meant that DDoS attacks that involved hundreds or thousands of sites that were hosting a handful of agents each, if they even calculated damages at all, would suffer “losses” only in the low thousands of dollars. Since each site would be looked at in isolation, conceivably none would meet the $5,000 limit, so pursuing prosecution would not be justified. If the victim was simply a public IRC server that did not have any paying customers, their losses could similarly be less than the $5,000 limit. There would be no case, even if in reality that one individual attacker had caused aggregate damages for a series of attacks that ran into the tens of thousands of dollars.

In some cases where there were multiple charges, for example, when a sniffer was used to capture user passwords as they were transmitted over the network, prosecutors would use the federal wiretap statute or “trafficking in access devices” (that is, the passwords) as the basis on which to prosecute. In other cases in which the suspect possessed credit card numbers, statutes involving trafficking of credit card numbers would be used. None of these statutes required proving a minimum amount of monetary damages (or any monetary damages at all).

A court decision in 2000, however, in the case United States v. Middleton did set a precedent in calculating damages. Nicholas Middleton worked as a system programmer for an ISP named Slip.net. He had intimate knowledge of how the system worked. He became dissatisfied with his job at Slip.net, and he quit. After quitting, he continued to use an account that Slip.net had given him, and used special computer programs to elevate privileges and delete accounts and files. His former employer tracked this activity to his account, and reported it to authorities. Middleton was arrested for causing damage to a “protected computer” without authorization, in violation of 18 U.S.C. §1030(a)(5)(A) and was later convicted [mid].

In the instructions to the jury on calculating damages, the court in Middleton stated:

The term “loss” means any monetary loss that Slip.net sustained as a result of any damage to Slip.net’s computer data, program, system or information that you find occurred.

And in considering whether the damage caused a loss less than or greater than $5,000, you may consider any loss that you find was a natural and foreseeable result of any damage that you find occurred.

In determining the amount of losses, you may consider what measures were reasonably necessary to restore the data, program, system, or information that you find was damaged or what measures were reasonably necessary to re-secure the data, program, system, or information from further damage.

Middleton appealed, but a higher court held that the calculation of damages was valid and that the “losses” suffered by the victims of computer crimes could reasonably include a wide range of harms, including the costs of:

1. Responding to the attack

2. Conducting a damage assessment

3. estoring the system and data to their condition prior to the attack

4. Any lost revenue or costs incurred due to the interruption of services

The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 [oJa] amended 18 U.S.C. §1030(e)(11) to codify the decision of the courts in Middleton. Under these changes, the government is now able to aggregate “loss resulting from a related course of conduct affecting one or more other protected computers”3 over a period of one year.

This also allows for including both attack phases of a DDoS attack, such that any subset of damages from the many sites involved can be aggregated, more easily getting above the $5,000 jurisdictional threshold. Of course, this does not mean that the FBI will investigate every case that involves damages over $5,000, but it does make it easier to meet the minimum required limit of damages.

8.7.1 A Cost-Estimation Model

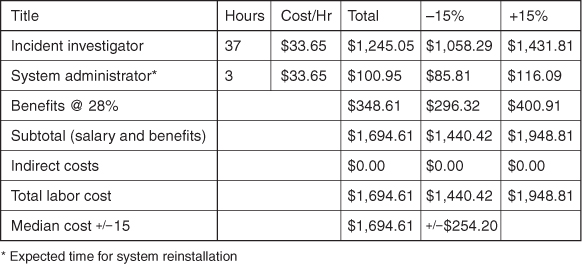

A model that is helpful for calculating such damages was developed as part of a study by a group of Big 10 (plus 1) universities. Called the “Incident Cost Analysis and Modeling Project” (or ICAMP) [oIC], the group used the following type of analysis.

• Persons affected by the incident were identified and the amount of time spent/lost due to the incident was logged.

• Staff/faculty/student employee time cost was calculated by dividing the individual’s wage rate by 52 weeks and 40 hours per week to come up with an hourly rate. The wage rate is then multiplied by the logged hours, and varied by + / - 15%.

• A benefit rate of 28% is added (an average of the institutions in the study) to come up with a dollar loss per individual.

• The total of all individuals’ time, plus incidental expenses (e.g., hardware stolen/damaged, phone calls to other sites), is then calculated using a simple spreadsheet approach.

This model is described in more detail in a FAQ (frequently asked question) file that was authored by David Dittrich [Dite], which includes references to an Excel spreadsheet that can be used as an example in calculating damages from an incident. The model is elaborated on in an article in SecurityFocus Online entitled, “Developing an Effective Incident Cost Analysis Mechanism” [Ditc].

Figure 8.1 shows an example of the incident costs associated with a break-in to a single computer. It includes only the response costs incurred by an incident investigator and the administrator of the system. Both of their salaries, when broken down to an hourly rate, are $33.65. You simply multiply these salaries by the number of hours spent, then include benefits and overhead costs. (In this example, there are no indirect costs.) Totaling up these costs, and including an error factor of + / - 15%, shows that the cost of cleanup for this single host is $1,695 + / - $254. The hardest part of this process is simply getting those involved to keep track of time spent, then doing the bookkeeping to aggregate damages within your organization. Many universities in the United States will frequently have hundreds or even thousands of computers compromised by a given worm or automated exploit, costing the better part of a day or more of time per computer to restore each affected computer to functionality. The total length of time to clean up all affected systems may extend to several weeks, or even months, in real time. The result is an unrecognized loss of productivity across the institution of hundreds of thousands of dollars per incident.

Figure 8.1. Incident cost table

8.8 Jurisdictional Issues

The above discussion of damage estimates and limits includes the term “jurisdictional threshold.” Since we are talking about federal statutes in the United States, this means the agency that will prosecute the computer crime is the United States Attorney’s Office, which means that the Federal Bureau of Investigation or Secret Service will be the investigative agency. The damages must be aggregated within, for example, an FBI field office.

Let us look at the FBI field office in the Central District of California. From their Web page [fbi], they describe their jurisdiction this way:

The Los Angeles Field Office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has investigative jurisdiction over the federal Central District of California. The Central District is comprised of seven counties: Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, and Ventura.

The Los Angeles Field Office territory is the most populated [in all of the FBI’s territories] with 18 million people residing within 40,000 square miles. The Los Angeles Field Office has the third greatest number of Special Agents in the FBI.

The Los Angeles Field Office headquarters is located at 11000 Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. The field office also has ten satellite offices known as Resident Agencies, which are located in Lancaster, Long Beach, Palm Springs, Riverside, Santa Ana, Santa Maria, Ventura, Victorville, West Covina, and at the Los Angeles International Airport.

What this means is that the aggregate amount of damage being estimated for prosecution within the jurisdiction of the Los Angeles field office includes only those victims in the area described above. The easier it is for the FBI’s various field offices to correlate incidents and calculate aggregate damages, the better chance they will be able to quickly identify a jurisdiction that meets the limit and to move forward with an investigation. All victims of computer intrusions who wish to support law enforcement (and to have a viable legal deterrent to computer crime) should take this into consideration and be prepared to produce accurate and timely damage estimates, e.g., using the methods discussed above.

Another jurisdictional issue has to do with which laws apply to a given computer crime. Is a sniffer a violation of state electronic communications privacy laws, or federal electronic communications privacy laws, or both? How about computer trespass statutes? These are typically state laws, if trespass into computers is recognized at all. There is a federal Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which may also have a state version.

Many large cities have police resources for investigating computer crimes, but these resources are often very limited. More and more crimes are beginning to involve the use of computers as instrumentalities of crime and/or repositories of evidence. As these crimes increase, the resources of local law enforcement will become even more strained. Much computer forensic analysis is handed off from local police to county or state police services, who may have more resources and training (although still not enough to investigate all cases involving computers). Regional computer forensics centers and joint FBI/Secret Service Task Forces are being formed across the country and are augmenting and coordinating computer forensic analyses and computer crime investigations, but there is still much to be done to keep up with the increase in number of digital devices that can be used for crimes, including things like PDAs, wrist watches, cell phones, digital cameras, and key-chain memory sticks.

8.9 Domestic Legal Issues

Let us now revisit the earlier attack scenario, only this time it is a much larger attack. Our attacker now breaks into 100,000 computers and builds a series of large bot networks. The attacker now goes after a site that receives on the order of $1 million per day in advertising revenue. The attacker has taken her time and knows the available bandwidth to the victim site, and understands the network topology and response capabilities of the victim’s upstream providers. She uses only sufficient numbers of DDoS agents at a time to take the site down, assuming it will be cleaned up over time by incident response teams and the attack capacity of the botnet will decrease over time. She brings in new attack networks at just the right time to keep the pain at a sufficiently high level. Using this tactic, the attacker can keep the attack going for more than a week.

Legal counsel for any victim should consider the following issues when determining what advice and which course of action to take after an attack:

• Negligence on the victim’s part. Consider whether there was negligence on the part of your client. Some issues to address are: (1) what precautions did the victim take prior to the attack to prepare for the possibility of an attack; (2) did the victim do an adequate risk assessment and balance defenses with insurance coverage to mitigate financial risk; (3) how did the victim respond to the attack once it was aware of the attack; and (4) was the response justifiable morally, ethically, and legally?

Addressing the preceding issues is important because it is likely that your client/victim may be called to account to shareholders, customers, subcontractors, or any others who may be financially harmed as a result of an inadequate or a legally questionable response by the victim.

The main message here is that counsel and client should perform an adequate risk assessment that addresses the prevention, detection, and reaction elements of information assurance.

• Criminal culpability. Consider whether your client/victim is able to identify a suspect in the attack, either through communications by the attacker that reveal an identity, involve a consistent communication method that can be traced back to the attacker, or through the legal discovery or investigative processes. It is best to provide this information to federal law enforcement as soon as possible to allow them an opportunity to investigate.

Where a suspect cannot readily be identified by the victim, the possibility of investigation still exists. However, if the attacker has taken advanced measures to cover her tracks and thereby remain anonymous, the possibility of a successful prosecution becomes much more difficult, if not impossible.

Either way, as mentioned in Section 8.7 regarding losses in criminal prosecutions, sufficient economic injury to the victim must be shown in order to meet the statutory limits required to pursue prosecution. Thus, it is important that any victim thoroughly assesses and collects evidence of the harm caused by an attacker.

• Liability. There are two primary types of liability that could apply in DDoS attacks. There is direct or “attacker” liability for the harm caused by an attacker, and indirect, or “downstream” liability, for the harm caused by those sites whose systems are compromised and used for an attack.

In an attacker liability suit, the person or persons responsible for the attack are sued. However, in a downstream liability suit, the plaintiff would be trying to prove negligence on the part of the owner of computers that were compromised and used to launch an attack against a third party. As previously mentioned, proving negligence involves showing, by a preponderance of the evidence, that four factors exist:

1. The defendant owed a duty of care to the plaintiff to secure their computers against compromise and abuse.

2. The defendant breached, or violated, that duty.

3. The breach of that duty was the actual and proximate cause of injury to the plaintiff.

4. The injury suffered by the plaintiff can be addressed by the awarding of damages.

The key here is establishing a duty of care which is judged using a “reasonable person” standard (i.e., what would a reasonable person do to secure her computer, and did the defendant fail to do at least the same?). In other words, negligence cannot exist where there is no preexisting duty, or where a duty cannot be established.

Laws that establish some form of requirement for computer security include the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act [Ele], which suggests a number of security measures that banks, credit unions, and other financial institutions should implement to protect their computer databases (and institutes civil and criminal penalties for businesspeople who do not adequately protect personal or financial information from compromise due to computer intrusions).

In the health care field, there is the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 [hip], which holds system administrators, information security officers, and administrators financially liable for disclosure of health-related information that could result from a computer intrusion.

It is important to note that liability cases are usually brought in local courts. Thus, trial venue may become another important factor that comes into play (e.g., where did the “damage” actually occur?).

8.10 International Legal Issues

Earlier, the relationship among city, state, and federal law enforcement was mentioned. Often, there are collaborative difficulties between law enforcement agencies at the various government levels. For example, county sheriffs may consider a crime to be in their jurisdiction and search and seize computers, only to have the FBI show up and claim jurisdiction, having to then argue about which agency has priority of possession over the evidence and the manner in which it was collected and handled. These issues get even more complicated when taken up to the international arena.

Criminal law is very well defined in the United States with regard to computer crimes. Internationally, however, there is very little law concerning computer intrusions. Laws concerning computer systems and electronic forms of data and property are quite different from country to country. In certain countries, computer data (information) is not considered property at all. (For more on international legal issues, see [int, oE, IAA, Lip02].)

In 1999, a study of available national legal codes concerning computer crimes in 50 countries around the world was performed by Ekaterina Drozdova, Marc Goodman, Jonathan Hopwood, and Xiaogang Wang. This study found that 70% of these countries had computer crime statutes,4 while 30% had few or no laws covering computer-related crimes.5 It is worth noting that a nation’s not having explicit statutes concerning computer crime does not mean that computer crime is legal there. The nation may use existing principles of law as applied to the new realm of computers instead. That has its strengths (well-established and understood laws) and its weaknesses (the analogy between the cyber and noncyber situations might be strained).

In November 2001, the Council of Europe released its final draft of the Convention on Cybercrime, [oE], which provides guidelines for members of the European Union in how to formulate harmonious laws regarding computer misuse. Chapter II, Section 1, states guidelines for formulating substantive criminal law as it pertains to several offenses. For our purposes, the critical elements are the unauthorized access of computers, data interference, system interference, and misuse of computing devices. These cover both phases of DDoS attacks. The Convention states that “each party shall adopt such legislative and other measures as may be necessary to establish as criminal offenses under its domestic law, when committed intentionally, the access to the whole or any part of a computer system without right.”

The Convention on Cybercrime attempts to address some of the legal imbalance found in the Drozdova survey. It states, “Given the cross-border nature of information networks, a concerted international effort is needed to deal with such misuse.” Chapter III defines the guidelines for international cooperation. Article 23 expresses the general tenor for the principles governing international cooperation:

The Parties shall co-operate with each other, in accordance with the provisions of this chapter, and through application of relevant international instruments on international co-operation in criminal matters, arrangements agreed on the basis of uniform or reciprocal legislation, and domestic laws, to the widest extent possible for the purposes of investigations or proceedings concerning criminal offenses related to computer systems and data, or for the collection of evidence in electronic form of a criminal offense.

Remaining articles define principles of extradition and other principles requiring mutual assistance among nations.

Extradition is important in cases in which crimes are committed by a foreign-based individual, and the victim’s government wishes to bring a suspect from another country before a court having proper jurisdiction. The case of Onel de Guzman, author of the “I Love You” computer virus, provides an example. Laws in the Philippines at the time de Guzman launched this virus did not consider computer data to be property, and the Philippines had no laws on their books covering computer intrusion or damage. The FBI quickly tracked the attack to de Guzman and had the cooperation of the Philippines federal police. However, when asked by the FBI to arrest de Guzman, courts in the Philippines could not help. Nothing could be done, despite the significant estimated worldwide damages, which ran into the millions of dollars.

In addition to needing a law under which to bring a criminal action, another requirement is that the act must be illegal under both jurisdictions in order for an extradition request to be honored. This is known as “dual criminality.” In the de Guzman case, he could not be brought back to the United States to stand trial here because he did not break any existing Philippines law.

In order to obtain extradition of a suspect from another country to the United States, federal law enforcement agents in the United States must first draft charges and go through a process called “letters rogatory,” which involves the Department of State’s producing the letters and delivering them to the foreign nation’s state representatives, who then in turn provide them to the foreign government’s federal law enforcement agents, who then issue a warrant for the suspect’s arrest, serve this warrant, and prepare to deliver the suspect to the United States federal law enforcement agents. Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs) that are established in advance speed up this process greatly, as does having a Legal Attache (LEGAT) from the United States FBI or Secret Service already in the foreign country and working closely with their federal law enforcement agency. Of course, the foreign government may refuse to arrest or extradite the suspect, which can cause a delay or derail a case. Interpol is one international police organization that tries to bridge this gap of international jurisdictional issues [BN].

The outlined legal procedures are clearly expensive, heavyweight, and slow. Thus, one cannot rely on them to help much in stopping an ongoing DDoS attack of international origins. At best, they may allow eventual prosecution of the perpetrator.

There are also issues of national defense that can come up in cases of massive DDoS attacks against corporations or agencies that provide “critical infrastructures,” such as banking, transportation, energy, telecommunications, etc. When does an attack on a business move from a criminal matter to a national security situation? Who is really attacking, and what damage do they intend to cause? While it may be clear that a direct attack on a military command-and-control network by a foreign entity that is clearly associated with a foreign military or intelligence agency could be interpreted as an act of war, it is not clear when or how a set of DDoS attacks on banks and airlines by an unknown entity would be interpreted as an act of war.

8.11 Self-Help Options

In the prior sections, we have seen many of the issues and impediments to federal criminal prosecution that lead some executives to doubt the ability of federal law enforcement agencies to pursue criminal legal remedies, and some of the options for civil remedies available to victims. There still are some who wish to take matters into their own hands and “do something” about being attacked.

This subject is sometimes called Active (Network) Defense, Computer Network Defense (CND) Response Actions, or the extreme form, the popular media term hack back.6, 7

This is a complex and controversial topic that is gaining in prominence in computer security conferences and discussion lists. David Dittrich maintains a section of his Web page that includes a significant amount of material on the topic (see http://staff.washington.edu/dittrich/activedefense.html). The as yet unpublished Handbook on Information Security [Bid05] will include an article by Kenneth Himma and David Dittrich titled, “Active Response to Computer Intrusions” that covers this topic.

One option that has very little real chance of working is attempting to counter a DDoS attack with a DDoS attack. There are just too many reasons why this is simply a foolish option to pursue.

• It is too easy for a moderate to highly skilled attacker to build large DDoS attack networks that cannot be overwhelmed by a counterattack. Moderate-sized botnets can easily reach 10,000 to 30,000 hosts, and large botnets of 140,000 hosts were seen as early as 2003 [Fis03]. There is simply no way that a victim can counter this kind of available bandwidth without further damaging its own network.

• Going after smaller subsets of bots, say in the 1,000 to 5,000 range, has similar problems with trying to match firepower, and if the attacker controls 140,000 hosts, it would be impossible to keep up with the influx of new attacking hosts, 1,000 here, 1,000 there, for as long as the attacker has more resources.

• Attacking back to attempt to disable hosts can have side effects that are unpredictable. Since such an attack may be disproportional to the traffic coming out of the DDoS agents, the owner of those systems may turn around and press charges against you. The attacker may control a host that is used for patient care, process control, etc., but using it to attack may not cause it to fail completely. Your counterattack, specifically designed to disable the host completely, may cause more damage than the original attacker, and you may be found by a court to be legally responsible for this damage.

• Can the desired goal be attained without risking even greater retaliation? If you do not know who is attacking you, and you do not know whether they have already penetrated your network or not, it is impossible to expect that a counterattack that is limited to attempting to remove their access to compromised hosts will actually achieve that goal. If you fail, and they have control of other resources in your own network that you are not aware of, they may simply use these to increase the damage to your network.

The bottom line is that a counterattack against a DDoS attack is almost certainly guaranteed to fail, or to cause more damage than it prevents. Such a counterattack is also likely to violate computer crime statutes at the state and/or federal level, and to potentially also violate statutes in other nations (where some of the DDoS agents and handlers you will be attacking may be located) and further increase your legal risk exposure. Regardless of how much it may seem to be worth the risk, the chances that your resources, knowledge about the attacker, skill level, and ability to execute a tactical and strategic counteroffensive, and do it in an ethically and legally justifiable manner, are very, very slim at best. Even if you were to succeed in such a counterattack, you would be creating congestion and harming many other Internet users who have nothing to do with either you or the attacker.

At this point in time, your best course of action is to follow the guidance in Chapter 6 to collect evidence of the attack, and to then contact the sites that are involved in the attack as well as federal law enforcement agencies, and to work cooperatively with all sites involved to respond to the situation.

8.12 A Few Words on Ethics

Not all problems are best solved by legal action. Our world operates because most of us agree on many ethical principles and normally act according to those principles. Should we not apply those principles just as much to our cyber behavior as our real-world behavior? Doing so would have a couple of implications concerning DDoS. We do not presume to provide moral answers here, but we would like to bring up a few questions.

First, if one ascribes to the ethical principle that it is wrong to needlessly harm others, one should consider if it is ever right to launch a DDoS attack against anyone, whether it be an offensive or defensive act. You will do them harm. You may very well do harm to third parties who you did not intend to strike. Is that right?

When viewed from the perspective of someone wishing to use DDoS as an offensive tool, there is no ethical justification. Even when viewed from a defensive perspective, as a countermeasure to an attack on you, DDoS is still hard to ethically justify.

Second, if you believe that it is unethical to offer assistance to another who is doing wrong, is it ethical of you to leave your computer in a state that makes it easy for a DDoS attacker to compromise? This is not a simple or trivial point. How much effort do you need to take to secure your computer? What if fixing a known problem requires crippling functionality that you rely on? This issue can be resolved only by considering one’s own personal morality and circumstances, but we urge all readers to spend a moment or two thinking about whether they are doing enough to protect their own computers, not just for selfish reasons, but to make it less likely that your computer assets will be used to perform a DDoS attack on another site.

There will always be people who have morality that allows them to perform actions like DDoS attacks without compromising their principles, and those who do not care for morality at all. So relying on morality to stop DDoS attacks is unrealistic. But perhaps applying a bit more simple morality to the cyberworld might stop a few attacks or make DDoS attacks a bit harder to perpetrate.

The ethical issues surrounding self-help options are covered in more depth in the same article, “Active Response to Computer Intrusions,” in the forthcoming Handbook on Information Security [Bid05] mentioned earlier, as well as in articles by the University of Washington professor Kenneth Einar Himma (“The Ethics of Tracing Hacker Attacks through the Machines of Innocent Persons,” [Him04a] and “Targeting the Innocent: Active Defense and the Moral Immunity of Innocent Persons from Aggression” [Him04b]).

8.13 Current Trends in International Cyber Law

A recent subject of discussion regarding liability of owners of the hosts that are compromised and used for DDoS attack is a pair of laws in Italy regarding civil and criminal negligence. To see how they apply, a hypothetical scenario will be used.

Let us say that A is the victim of a DDoS attack, and this attack can be traced to one or more computers owned by B. If a post-mortem analysis of B’s computer is performed, and it shows that B has not applied the “minimum security measures,” then A has a civil cause of action against B and can bring suit in Italian civil court for an article called “damage refund” under the Italian civil code. (This is similar to what was discussed in Section 8.9.)

What is more, there is a law in Italy (196/2003) called the “Privacy Law.” This law requires that the appropriate/minimum security measures for information security are mandatory if an information system stores sensitive, personal, and judiciary-related data. If an incident occurs, and the owner of the information system is found not to be compliant with the law, they may be levied a penalty of 50,000 euros and three years in jail. This means that if A is attacked using a compromised host owned by B, and B’s compromised machine contains sensitive data, and a post-mortem analysis (even conducted by the police) demonstrates that the minimum security measures were not applied, then B may be brought in front of the court for violation of both laws.

This privacy law is new, so as of publication of this book there was no case law to cite. Italian Web sites that store personal information will have a privacy statement mentioning law 196/2003.

As discussed in Section 8.2, the primary law in the United States that may apply to DDoS attacks is the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. The example cited, United States v. Dennis, prosecuted a DoS attack under 18 U.S.C. §1030(a)(5), “interfering with a government-owned communications system.” This law clearly applies to government-owned systems, and other “protected computers.” A very good explanation of its application to date, and some proposed changes to the way that the terms unauthorized and access are interpreted, can be found in a 2003 New York University Law Review article by Orin S. Kerr [Ker03].

A similar law to the CFAA in the United Kingdom is the Computer Misuse Act (CMA). During the early part of 2004, a group called the All Party Internet Group (APIG)8 held an inquiry into the CMA [api04]. Their inquiry notes the same cases of DDoS-related extortion attempts cited in Chapter 3, and the efforts of the British High Tech Crimes Unit to investigate them. They also cite the same case of a DoS attack involving the Port of Houston. Further, they point out the same issue of the two phases of DDoS attacks, stating:

In general, where a DDoS attack takes place then an offense will have been committed because many machines will have been taken over by the attacker and special software installed to implement the attack. Even when a system is attacked by a single machine, an offense will sometime be committed because the contents of the system will be altered.

Their recommendation is the creation of a new offense of “impairing access to data.”

An even more interesting recommendation made by APIG is founded on the same evidence discussed earlier in this chapter of limited resources on the part of law enforcement, and the impression of some victims that there is no effective law enforcement response option available to them in all but the largest cases. This situation creates a negative value in their opinion of laws that are on the books, but provide no realistic deterrent due to very low prosecution rates. Their recommendation is to build on an ancient right, preserved under s6(1) of the Prosecution of Offenses Act of 1985, for individuals to bring private prosecution. They explain that the first step is for the individual making the claim to “lay an information” before a magistrate, who then decides whether or not to issue a summons. If he does, a criminal trial will ensue.

To implement this recommendation, they suggest following the recommendations of another group, EURIM (the European Information Society Group). In a EURIMIPPR e-crime study working paper titled, “Working Paper 4: Roles and Procedures for Investigation” [eur04] recommends several things:

• Creation of joint private industry/law enforcement crime units, and establishment of guidelines for the creation, governance, and operation of such units.

• Develop guidelines with industry for handling requests from private investigation teams for supporting services for which only law enforcement are authorized.

• Develop a scheme for the exchange of investigative and forensics experience, best practices, and tools within communities.

• Investigate with representatives of law enforcement, industry, and other interested parties the possibility of investigators and others in industry with appropriate skills and experience being accredited to work to the same legal and operational standards and guidelines as law enforcement when involved in e-crime investigations.

The effect of these two bodies of recommendations would be to (1) make criminal the act of denying access to data and information systems; (2) create a cadre of trained computer security professionals in private industry who have special, but limited, authority to investigate these crimes (perhaps closely involved with law enforcement); and (3) to permit these private security service companies to bring private prosecutions under the CMA (with the right reserved by the Director of Public Prosecutions to take over, decline to provide evidence, or withdraw the case).

Relating the APIG proposal back to the United States, this proposal includes components that are similar to those put forward in the United States in a 1998 law review article by Stevan D. Mitchell and Elizabeth A. Banker entitled, “Private Intrusion Response” [MB98]. This paper came out of work during the Clinton administration by the President’s Commission on Critical Infrastructure Protection (PCCIP), in the Critical Infrastructure Assurance Office (CIAO) [pcc97, itCD97].

It will likely take some time—and much needed debate—before the issues brought up in these proposals are resolved. Similarly, it will take time before there is enough case law under new statutes to determine if a positive effect has been achieved on reducing cybercrime in general, or the use of DDoS as a means of engaging in other criminal activities.