Managing Stress

7

The work of portfolio, program, and project managers involves a large number of stakeholders across a variety of organizational boundaries. The tasks performed by these managers are complex and involve interactions with many people who have different points of view. In addition, portfolio, program, and project managers are often expected to produce results within limited periods of time and with less than optimal resources. And because global, virtual teams, on which around-the-clock work is possible if it is planned and managed effectively, have become more common, there is an even greater emphasis on quickly completing programs and projects.

Both mxanagers and team members experience stress to varying degrees when working on a program or project. Turner, Huemann, and Keegan (2008) write that additional pressures are created each time a new program or project starts or an old one finishes, as the configuration of human resources in the organization changes. People in project-based organizations feel stress for several reasons:

The peak in workloads at unpredictable times makes it difficult for people on programs and projects to achieve a workload balance.

Uncertainty about future assignments: Will there be a future assignment, and if so, where will it be located, and what will the role and responsibilities entail?

Will the new assignment be in line with my career objectives?

The authors conclude that it is a challenge for people on programs and projects to manage these pressures; both the individuals themselves and organizational leaders need to take positive action.

What causes stress for you in your role as a portfolio, program, or project manager?

What do you notice when you answer this question? Maybe an event begins to surface from your memory, something that was upsetting for you. Possibly a feeling begins to emerge, such as anger or anxiety. As you formulate your answer to this question, consider these “truths” about stress:

What is stressful for you is not necessarily stressful for someone else.

Stress is neither good nor bad; all events that are perceived as stressful can have positive components.

The best approach to handling stress is to develop a strong sense of your personal style, your own sources of stress, and the most adaptive methods you use to reduce stress. As Aitken and Crawford write, “Understanding how project managers cope with stressful situations is the first step to being able to manage their outcomes, both positive and negative” (2007, p. 667).

Inherent Sources of Stress in Project Management

A number of challenges inherent in project management create a stressful work environment for the project manager. These include the intrinsic stress of being a project leader, the matrix management style of leading, the challenge of solving singular problems, project ramp-up and ramp-down (Table 7-1), and virtual teamwork.

Being a Project Leader

A project manager faces two types of inherent stressors in the role of leader:

The pressure to create a culture or “container” in which the team functions

The tendency for team members to project numerous feelings, motives, and attributes onto the team leader.

The notion of a leader creating a positive culture for the team suggests that the leader must expend personal energy and resources to create an atmosphere in which the team will operate successfully. This kind of team atmosphere does not simply happen; the project leader must strive on a personal level to create an approach that holds the team together. Individuals do not coalesce into a team without the leader exerting energy to create a bond within the group.

Table 7-1 Inherent Stress in Project Management

| Source of Stress | Type of Stress Placed on Project Manager | Optimal Stress-Management Approach for Project Manager |

| Intrinsic stress of being a project leader | Creating a positive atmosphere for teamwork | Enlist team members to develop a team culture. |

| Matrix management systems | Pressure to build a team quickly and efficiently | Develop the skills of influencing others, clear communication, and conflict resolution. |

| Singular problem- solving | Challenge of solving unique problems for the first time | Develop an ability to embrace problems and stress on a day-at-a-time basis. |

| Project ramp-up and ramp-down | Demands energizing oneself on intellectual and emotional levels and an ability to function in an atmosphere noted for a lack of continuity, stability, and predictability | Develop the ability to intellectually and emotionally pace oneself through positive self- talk, diet, and relaxation strategies. |

A project manager applies a positive atmosphere to bring his or her team together when he or she:

Stays late on a Friday afternoon to meet with team members to help them work through a personal disagreement

Publicly acknowledges the hard work and achievements of all team members

Finds the personal strength to motivate the team after a frustrating period of project delays and setbacks.

The project manager should remember that these efforts require physical, emotional, and intellectual energies. Do not overextend yourself by trying to develop a team culture solely on your own. Enlist team members to help you create the glue that bonds the team together.

The second general component of leadership that can prove stressful for the project manager is team members’ tendency to project their own feelings, attributes, or beliefs onto the project manager. In essence, team members assume that the project manager has certain qualities—either positive or negative.

Project managers enjoy being the target of projections that are positive— for example, if a team member projects the belief that the team leader is a fair person, possibly because the team leader physically resembles a fair person from the team member‧s past. But negative projections, such as when a team member attributes bad motives to the project leader because the leader reminds him or her of a previous manager with whom he or she had a conflictual relationship, are a source of stress for the project manager. Examples of problematic projections that team members may direct toward the project manager include:

Treating him or her like a parent (which may have a positive or negative tone)

Making assumptions about his or her attributes based on gender, race, religion, or age.

If you believe that you are the target of a team member‧s inaccurate projections, it is helpful to:

Schedule time to speak privately with the team member, gently exploring his or her perceptions of you without immediately challenging his or her observations.

Attempt to redefine for the team who you are as a person, telling members about your management style, your beliefs, and how you like to operate.

Managing in a Matrix Organization

Many projects are staffed by individuals who are on loan to the project from other functional areas within the organization. This is the core of matrix management. The project manager may encounter a number of issues and events arising from matrix systems that will be stressful. The biggest challenge for the project manager is influencing people to get the job done while knowing that the working relationship is temporary, lasting only for the duration of the project.

Because the project manager within a matrix system must use influence to obtain results, he or she may experience a feeling of powerlessness when the influencing behavior fails to work. Project managers often report that this feeling of helplessness accounts for a tremendous amount of stress in leading projects.

When a project manager experiences these feelings of helplessness, stress quickly develops. Internal pressure mounts, and if the helpless feeling continues unchecked, the project leader loses motivation and initiative. Some thoughts to keep in mind when trying to manage stress in matrix systems:

Matrix organizations are known for their ability to create a sense of power- lessness, even for the best managers. Do not take the situation personally.

When influencing is not effective, use more subtle forms of personal empowerment, such as making arguments that appeal to the self-interests of the various stakeholders.

Solving Singular Problems

Each project is unique, designed to solve a singular problem. Singular problem-solving represents both the best and the worst of project work. It gives team members a chance to work on something new and different, unlike anything they have done in the past. But solving singular problems can also pose many stressful challenges for the project manager. By definition, a singular problem is one that a team has never faced, so there may be no readily available solutions, software, or technology to apply to building the finished product or to deliver the promised service or result. Everything has to be invented, from the conceptualization and design of the solution to the manufacture of the tools for doing the work.

All of these factors place great demands on the project leader. Team members are looking for direction and support and may need guidance on how best to proceed. Their emotions may be running high, and they may feel anxious and uncertain, not wanting to take a step and risk making a mistake.

Project managers can handle the stress that comes from solving singular problems by considering the following suggestions:

Keep motivated by focusing on the positive aspects (e.g., novelty, challenge) of solving a problem for the first time.

Remember that it is understandable to feel uncomfortable when attempting something new. Avoid self-critical comments such as, “There must be something wrong with me because I cannot figure out how to get this solution started.”

Keep in touch with other professionals. They may be able to suggest problem-solving approaches that may not have been considered.

Use the organization‧s knowledge management system to research whether other programs or projects had similar difficulties. If the organization lacks a commitment to knowledge management, suggest that it set up such a capability.

Ramping the Project Up and Down

The periods of project ramp-up and ramp-down may cause pressure and stress for the project manager. Some individuals react more positively than others to the emotional and physiological ramping up at the start of a project. In fact, some people thrive in these settings, enjoying the rush of energy and the exhilaration that come from starting something new and demanding. These individuals can be considered sensation-seeking people who need to have their physical and emotional systems regularly exposed to this type of emotional and physiological activation. During these periods of arousal, sensation- seeking people feel more alive and creative and are often operating in their most positive mood state.

However, not everyone is a sensation-seeking individual, and project managers should not underestimate the demands that ramping up and ramping down can have on the emotional and physiological well-being of their team members as well as themselves. The project life cycle is demanding and requires that the individual operate in an environment that is intense and constantly changing.

Project managers who repeatedly experience discomfort during this life cycle need to take a serious look at whether the role of project manager is the most appropriate one for them to play. Some people, regardless of length of service and best intentions, do not function well as leaders during these demanding periods. For these individuals, taking another role on the team may be a healthier career decision.

Project managers can attempt to take care of their emotional and physiological reactions during project ramp-up by considering these ideas:

Place a vocational pursuits off to the side during this period.

Take the steps of the ramp-up process one at a time. Stress and discomfort increase when the project manager experiences anticipatory anxiety, which is caused by excessive focus on future events over which one has little current control.

During project ramp-down, the project manager can manage personal stress by remembering that:

Endings involve a sense of loss and frequently a melancholy mood, even when the ending brings great success and achievement. Occasionally, team members may find it difficult to complete the project and finish all the necessary closeout tasks.

Endings also involve saying good-bye to team members, which can cause natural but unexpected sadness.

As ramping down is concluding, it is crucial to take stock of how one is feeling emotionally, intellectually, and physically. Some recharging of the batteries may be necessary, such as a weekend away or time with friends.

Remember, the savvy project manager has a strong self-awareness of how he or she functions during the ramp-up and ramp-down stages and crafts coping strategies to address individual problems that may surface at both ends of the cycle.

Research by Turner, Huemann, and Keegan (2008) concludes that people experience more stress when working on a typical small or medium-sized project that can be completed in a short time than on a program or on a project that is of longer duration. Typically, programs last longer than projects, and on a program, it tends to be easier to plan each person‧s work. People also are less concerned about the next assignment or whether they will even have a next assignment.

On many projects of small to medium size, stress is a greater concern. These projects tend to last between three to nine months, which means that it is challenging

to pace the work. Customers have key milestones, and time is the dominant of the triple constraints. It is difficult on these projects for people to take vacations or personal days to pursue other interests. It also is hard to plan how many people, and what kinds of people, will be needed to do the work, which puts pressure on the project manager when he or she tries to coordinate with people from the human resources department. Additionally, it is rare for a person to be assigned to work on only one project, and this then presents other time-management challenges. Consider the following situation.

Assume you are working for a consulting company that primarily bids on work from the U.S. federal government. The government makes many awards just before the end of the fiscal year so that agencies can use any unspent or end-of-year money. Your organization tends to work hard in the spring and summer to submit as many proposals as possible for its consulting work in project management. This year, the company won 90 percent of the bids it submitted and is extremely pleased that its proposals were accepted.

However, last year, its win rate was only 40 percent, and its capture ratio was even lower. As a result, the company downsized. Now it does not have enough people to do all the work it has won. This means there is excessive stress on the project managers and team members until additional staff with the necessary competencies can be hired and can learn the organization‧s project management procedures and about the work to be done for the various customers.

On top of this problem, your company has never worked with many of the customers before. Additional sources of stress for project managers include working to understand the customers’ culture, gaining their confidence and trust, and identifying the key stakeholders with whom they will work. Project managers become overwhelmed with the work they must do and the many projects they must manage. They have less time to spend one-on-one with their team members, developing personal relationships and ensuring their well-being.

To cope in this environment, explain the situation to your team and let them know the organization is working hard to hire additional staff or contractors until full-time staff are available. Hold weekly meetings or conference calls if you are working in a virtual team, thank people for their hard work thus far, and inform them of progress in hiring new team members to support the project. Work actively with the human resource department to prepare needed job descriptions and other materials to accelerate the hiring process, and let your team know that you are actively involved in this way.

Working on a Virtual Team

People new to a virtual environment may find that they are taking on a different type of assignment outside their usual comfort zone. They are interfacing with different stakeholders at different levels, most of whom they have not worked with previously or even known about at all. They may feel lonely because they are not able to regularly interact with team members. Cultural differences, the use of a language on the program or project that is not one‧s native language, and a lack of solid understanding of how best to interact with other team members can add to stress for people in a virtual environment. The program or project manager must spend additional time with individuals who are struggling on a virtual team until they feel comfortable.

Inherent Sources of Stress in Program Management

While program managers experience some of the same types of stress as do project managers, program managers have even more responsibilities. These managers are not responsible for only one project, but for a multitude of projects with interdependencies among them, along with some nonproject work, and they must interact with an even greater number of stakeholders, many of whom are external to the performing organization. The longer life and complexity of a program may be especially stressful to the program manager. He or she may have trouble envisioning how the program will achieve all its planned benefits and come to a close. Even if the program finally comes to a close, the program manager is responsible for transitioning the benefits to the organization in a sustainable way. There may also be additional pressure on the program manager to be a leader and an effective communicator. Table 7-2 summarizes the stressors the program manager faces.

Managing Several Projects Plus Ongoing Work

The program manager will have a number of different projects in his or her program, in addition to other ongoing work or nonproject work. Some of these projects may have started before the program, and these projects with their interdependencies may be the reason the program was initiated. Other times, programs begin, and projects are initiated later. Regardless, projects can be initiated at any time during a program‧s life cycle except during the closing process, and the program manager is responsible for ensuring that all of the interdependencies are identified and determining how best to manage them. According to PMI (2008b), managing these interdependencies involves:

Coordinating the supply of components, work, or phases

Resolving resource constraints and other conflicts

Integrating activities across components

Mitigating risk actions across components

Ensuring that the program remains in alignment with the organization‧s strategic goals

Resolving issues by escalating them to a governance board that may address scope, time, cost, and quality.

Tailoring procedures as needed and managing interfaces.

Table 7-2 Inherent Stress in Program Management

Because programs are complex and important to the organization and typically take longer to complete than an individual project, any of the activities listed above can be a source of stress. One way to approach these challenges is to prepare a program work breakdown structure (WBS) by working with the project managers. Involving the project managers in the program WBS has two advantages:

The project managers believe they are integral to the overall success of the program in the early stages.

The project managers can ensure that the control accounts and work packages for their project are considered and recognized by the program manager and other project managers.

The program manager should have a group meeting (if working in a virtual team, a teleconference or computer-aided meeting) so that all of the project managers can work together to prepare the program WBS. Then, when a new project is added to the program, the project manager should prepare a WBS for his or her project, and the program manager should hold another meeting of the project managers to update the program WBS and to show everyone how the new project interfaces with the existing projects.

Another key source of stress at the program level involves resource allocation. While certain resources are critical to each project, familiarity with the knowledge, skills, and competencies of all of the human resources on the program can help the program manager allocate and reallocate resources. It may be that a key subject matter expert is required for one project in the program. However, another project may also benefit from this individual‧s contribution to certain deliverables. The program manager can set up a profile outlining each individual‧s capabilities and use the profiles to determine how to best use the available resources.

To complement the program WBS, a resource breakdown structure (RBS) and a RACI (responsible, accountable, consulted, informed) chart should be prepared at the project level and then rolled up to the program level. The program manager can use these documents to see when certain key resources are required on various projects. Then he or she can work with the respective project managers to determine how to best use the talent available. Such an approach also can help the program manager obtain resources who are not assigned to the program. If it is evident that the program requires a resource who is not assigned to the program, the program manager can work with the governance board and the human resource management group to find someone with the needed skills.

When working with project managers, the program manager should:

Establish a climate of open communication so that moving a resource from one project to another does not add to the project manager‧s stress.

Talk one-on-one with the project manager before reallocating a resource to determine the impact on the project.

If reallocation presents a major challenge to the project manager, see if a compromise can be reached with the other project manager, and set up a mutually agreeable timetable for switching the resource.

Publically acknowledge the willingness of the two project managers to work together to resolve this issue so that everyone else can see the benefits of teamwork and compromise.

Risks to the program are another area of stress. While it is impossible to identify all risks that may affect a program, because there will always be some unknown unknowns, the program manager must work collectively with the project managers. A risk identified on one project may also affect an interdependent project. Each project manager should prepare a risk management plan and share it with the other project managers. These plans will be used to help develop the program risk management plan.

When a risk actually happens, whether or not the proposed response is effective, the project manager should notify the program manager so he or she can inform others as required. The project manager should follow established escalation practices without fear of repercussions; similarly, the program manager should escalate risks as required to the sponsor or to the governance board. It may even be necessary to involve the portfolio review board if the risk is so significant (as an opportunity or as a threat) that it could affect a program or project under way in another part of the organization. An atmosphere of open communication is critical to help reduce the stress associated with risks in the program management environment.

Working with Numerous Internal and External Stakeholders

At the program level, there are far more stakeholders, both internal and external, than at the project level. Identifying and working with the various stakeholders at different levels is a complex process and a significant source of stress for program managers.

Each stakeholder group will require different types of information and will probably be actively involved in some phases of the program and have less influence and impact in others.

It is possible to overlook a key stakeholder even if the entire team works to make sure that this does not happen.

Each time a new project is added to the program, new stakeholders will be involved, which means the stakeholder management plan and stakeholder management strategy must be updated.

To help reduce this stress, program managers should:

Work with the project managers and the team to ensure stakeholder planning, identification, and management are ongoing throughout the program.

Hold special meetings with the project managers and team members as needed that focus specifically on stakeholders: Are stakeholders receiving the information they need, or do they require additional reports and meetings?

Meet regularly with the sponsor and the governance board, not just at key phase or stage gate reviews, but at other times to discuss the overall health of the program with a focus on stakeholder management. Sponsors and board members may have their own concerns and also may have come across a key stakeholder who is not included in the program‧s stakeholder management plan and strategy.

Track activities underway to make sure someone from the team is working with the associated stakeholders.

Periodically conduct surveys of stakeholders, using open-ended questions, to gauge their reaction to the program thus far and to ask how the program could better meet their individual needs.

Being a Program Leader

The stressors that affect project managers also affect program managers, but they are magnified at the program level. The program manager must constantly reinforce the purpose of the program to team members and stakeholders. He or she also must bring the team together even if its members are scattered across the globe and may never meet face to face as a group. Further, he or she must apply personal energy to building and maintaining the team, and this energy must continue throughout the long life of the program.

The program manager must make an effort to be viewed as a person who is fair and objective and who treats people at all levels with respect. He or she must have an open door policy with a co-located team. On a virtual team, the program manager should inform the team of his or her availability to speak on the phone and how quickly he or she will typically respond to emails.

If the program manager believes or learns that others think his or her leadership and communication skills need improvement, the best approach is to practice active listening and ask people for candid feedback. It may be difficult to not take a defensive posture, but feedback is important for anyone who strives to continually improve. Based on this feedback, it may be appropriate to call a team meeting to discuss what you, as the program manager, plan to do to improve your leadership and communication skills and your own operating style in the program. Later, you might ask the enterprise project management office to conduct an anonymous survey of your team to determine whether its members think you have made positive changes—and, more important, to find out what else you might do to improve.

Transitioning Program Benefits

Managing projects with interdependencies as programs reaps benefits that would not be realized if the projects were managed in a standalone way. In addition, most programs contain some elements of ongoing or nonproject work. The expectation of greater benefits means the program manager is under greater stress from the beginning than a project manager.

Not only must additional benefits be realized from the program structure, but there are also more deliverables associated with the program.

The benefits are listed initially in the business case but expand over time, so by the time the program manager is assigned to manage the program, he or she may have even more benefits to manage.

Projects will be canceled or completed and closed at different times. When projects are closed, their associated benefits must be transitioned to customers, end users, or a product or customer support organization. This means the program manager is responsible for benefit realization from each individual project, plus benefits from the program as a whole. In addition to this, he or she must consolidate the benefits, transition them, and manage the transition effectively so that the benefits are sustained.

For many team members, the concept of a benefit may be new. PMI (2008c) defines a benefit as “an opportunity that provides an advantage to an organization” (p. 309). The program manager must define the benefits the program is to provide in a way that allows each member of the team to see his or her role in their delivery. The program manager also must make clear to everyone on the team the importance of benefit identification, planning, execution, monitoring, and control, as well as completing deliverables on time, within budget, and according to specifications, and meeting customer expectations.

To illustrate each person‧s contribution to overall benefits management and to reduce each person‧s possible anxieties about the importance of benefit management, the program manager can:

Hold brainstorming sessions or use other group dynamic approaches to involve the team in the benefit identification process.

Have the team prepare a benefits realization plan at the project level, which then is rolled up to the program level and maps to the program management plan so that each person can see how he or she is to contribute.

Work with the team to develop metrics that will show how and when benefits are realized and that indicate whether any benefits cannot be realized as planned.

Meet individually as needed with team members if the team is co-located, or through phone calls if in a virtual environment, to stress the importance of benefit management to team members who may not have experience with this requirement.

Many organizations have product or service departments that are responsible for sustaining program benefits. A consultant was hired to assist one such department that was having several problems communicating with the organization‧s program group. For example, the service department received no notice when it was to assume operational responsibility for a completed program, and it was unable to perform capacity planning and had to be on standby or use an informal network to learn of upcoming work. The consultant worked to help this department set up a project management office (PMO) and, more important, a process to align communications with the program group. The consultant suggested that the service PMO director set up formal weekly meetings with the program group and ask to be included as an observer in program-group reviews to learn about upcoming work. The service PMO director explained to the program group that his department had to be ready to support the program group‧s important work and that the use of proactive, horizontal communications could greatly assist him in doing so.

Often the recipient of the program benefit is not involved until the individual project or overall program is complete. He or she may know the program is underway, and if this person, for example, represents a product support or customer support group, may know that ultimately it will be his or her responsibility to sustain these benefits. At times, however, this key stakeholder is overlooked or is an afterthought; if the stakeholder finds out about this upcoming responsibility without time to plan for it, additional stress may be placed on the program manager. The program manager may need to ask the governance board for resources to continue the program even when it should be closed until this support group is able to assume responsibility.

To avoid the need to continue to support the program after it is complete, the program manager must ensure the ultimate group responsible for benefit sustainment is aware of the program and when specific benefits from each project and the program as a whole are expected to be delivered. The program manager should:

Meet with the group responsible for sustainment early in the program and ask them how they wish to be involved. For example, do they wish to receive regular updates on progress and benefit realization reports, attend team meetings from time to time, or have regular involvement even as a member of the governance board or steering committee?

Provide as much information as possible, perhaps through the joint development of a benefit transition plan to the receiving organization so they are prepared and can assume ownership once the program is closed.

Ensure the receiving organization has access to the program‧s knowledge repository.

Be available after closure in case the receiving organizational head has any questions, and be able to put members of the receiving organization in direct contact with program team members as required.

Inherent Sources of Stress in Portfolio Management

Stress levels differ at the portfolio level, although the portfolio manager is still responsible for being a leader, an outstanding communicator, and an effective manager of stakeholders. Project-based organizations’ portfolios contain both internal and external programs and projects. In such a portfolio, people can work on different projects at different times, often in different roles. This means there can be role conflict, which, combined with the demands from program and project managers, add to stress. It is more difficult to achieve a work-life balance because the workload on the different programs or projects peaks at different times—or even at the same time, which maximizes stress on the individual and can ultimately lead to burnout.

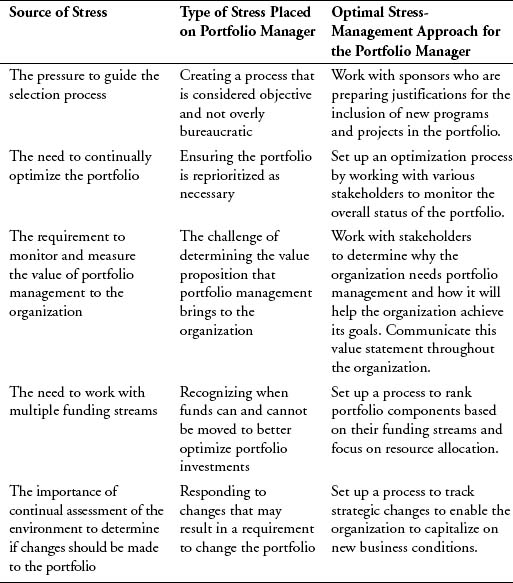

The portfolio manager also faces pressure to guide the selection process, to continually work to optimize the portfolio, to measure and monitor the value of portfolio management to the organization, to work with multiple funding streams, and to continually assess the environment for changes that may affect the portfolio (Table 7-3).

Table 7-3 Inherent Stress in Portfolio Management

Guiding the Selection Process

Portfolio management represents a culture change for organizations. No longer can people work on programs and projects they feel will be of benefit to the organization; instead, they must follow a detailed selection process that will be used to evaluate whether to fund and allocate resources to a program or project. The portfolio manager may experience stress because he or she must:

Describe why this process is being followed

Provide guidance to people about what must be done to make the business case for a program or project and how to structure it so it is carefully considered by the portfolio review board

Communicate to the proposer the decision of the portfolio review board, which, of course, is extremely difficult if the decision is not to fund the proposal.

The portfolio manager also may be tasked with developing the selection process, which requires analytical skills, as well as communication skills—the portfolio manager must explain the process to people at all levels and get their buy-in to the new process. Additional responsibilities that may cause stress include coordinating the development of the selection process with others in the organization and evaluating the selection process periodically to make sure it is serving its purpose and is not considered cumbersome and too bureaucratic to follow.

Once the selection process has been set up, the portfolio manager should work with program and project sponsors as they prepare their business cases to make sure they understand items to include. If a sponsor‧s business case is not accepted by the review board, the portfolio manager must inform the sponsor about why it was not accepted—which could bring on even more stress. (When the portfolio manager delivers bad news, he or she should focus on pointing out why other programs and projects were selected over this one and on ways to better justify the proposal before the next meeting of the board.)

Optimizing the Portfolio

Because a portfolio is not static, the portfolio manager must work with the portfolio review board to continually optimize it. Rebalancing is an ongoing occurrence as new programs or projects are added to the portfolio, others are terminated after board meetings, and others are completed as planned. These frequent changes are typically stressful for the portfolio manager.

With each change, the portfolio manager must communicate decisions to the various stakeholders and also must work to reallocate resources to newer, higher-priority work. The portfolio manager must have negotiating skills to work with the various program and project managers involved. In determining the most optimal mix of resources, the portfolio manager can enlist the support of existing program and project managers for changes.

Ultimately, however, the portfolio manager usually makes decisions about the portfolio mix with support from the review board. It is common for these decisions to engender resentment in people who are moved from their existing work to a new program or project as well as in their managers. The portfolio manager must explain why the changes are occurring and individuals’ roles in the process. He or she may be able to negotiate with displaced employees’ new program or project managers so they can at least be available for consultation or can return to their previous assignments once they have completed their new assignments.

The portfolio manager can simplify the portfolio rebalancing process and minimize the associated stress by:

Continually performing capacity planning so that he or she can inform the portfolio review board of the impact of portfolio changes

Communicating as often as possible with program and project managers whose work is considered to be high or medium priority about changes that may affect the portfolio so that any change is not viewed as a complete surprise

Consistently providing information to everyone in the organization about the value of the portfolio management process and any changes so that the process is as transparent as possible.

Monitoring and Measuring the Value of Portfolio Management

While every organization has some kind of portfolio, not everyone in an organization may be aware of the actual portfolio of programs, projects, and other work. If an organization has a defined portfolio-management process, involving a portfolio manager and a portfolio review board or comparable group, the portfolio manager may be under pressure to show the rest of the organization—at the executive level and at lower levels—why this process is valuable. If others in the organization do not understand the value of the process, the portfolio manager will struggle to get buy-in; people will feel their time is better spent elsewhere.

Senior executives on the portfolio review board may not appreciate a process that prevents them from pursuing pet projects they believe are essential to the organization, and they may not wish to be part of the formal portfolio selection process, may not take the process seriously, and may delegate attendance at board meetings to others rather than actively participating in them.

The portfolio manager can prepare a thought paper or white paper that concisely describes why the organization is following a structured portfolio management process. People need information about:

Why portfolio management is important

The tools and techniques being used

Specific roles and responsibilities

The overall value a defined process brings to an organization.

To prepare this thought paper, the portfolio manager should:

Draft a value proposition for portfolio management that states its goals, objectives, and benefits and how they will be monitored and measured.

Work with stakeholders in a cross-functional group to review and revise the thought paper. List factors for the success of portfolio management in the organization.

Submit the thought paper to the members of the portfolio review board for their buy-in and comments.

Circulate the thought paper throughout the organization.

Working with Multiple Funding Streams

Many organizations have multiple funding streams. This is typical in consulting firms, a joint venture, or a joint services organization such as in the Department of Defense or other governmental agency. In this kind of environment, the portfolio manager cannot move funds from one funding stream to pursue a project or program that is considered to be of higher priority and importance but is not covered by the funding agent. He or she must have an in-depth understanding about what can legally be done and what cannot be done and must be able to explain the process to stakeholders at various levels. The portfolio manager may be put in a difficult position if executives want to execute a program or project but lack the needed funds to do so. A portfolio manager who is frequently in this situation must have skills in resource allocation techniques, trade-off analyses, negotiation, and decision-making to help manage the stress associated with the position.

Assessing the Environment for Changes to the Portfolio

With the increase in downsizing, joint ventures, outsourcing, and off-shoring, as well as the need to keep up with and outpace the competition, the portfolio process is characterized by constant change. To help mitigate the stress these changes may bring, the portfolio manager should strive to:

Build relationships with people in the organization who work in strategic planning, marketing, sales, and business development

Cultivate relationships with people who specialize in organizational change to help prepare people at various levels for these changes

Recognize that the portfolio management process is not a static one. Even if there are no changes, it is helpful to review the criteria from time to time to see if they are still applicable and to practice a policy of being receptive to and embracing change.

Stress Caused by Dysfunctional Organizations

Organizations operating in dysfunctional ways create stress for managers. A dysfunctional organization is one in which formal or informal processes and culture operate in ways that are not healthy or conducive to a positive work atmosphere. Too frequently, portfolio, program, and project managers working in a dysfunctional system become lightning rods for all that is wrong with the organization simply because they are prominent people at the center of the action.

One way to combat dysfunction is for organizations and leaders to demonstrate congruence between spoken or written words and actions. This is “walking the talk.” When people or organizations say one thing but do another thing, this lack of congruence heightens the stress level for stakeholders. A lack of organizational congruence is more than simply a nuisance for team members and portfolio, program, and project leaders. People who are repeatedly exposed to situations in which a lack of congruence exists frequently display a variety of troublesome symptoms and reactions. For example, when people notice that organizational words and actions do not match, they are often puzzled, saying, in effect, “Am I wrong in my perceptions or is the company wrong?” This creates self-doubt, and this self-doubt can begin a spiraling process in which the person loses motivation and becomes chronically distrustful or cynical.

A situation involving a lack of organizational congruence is a no-win situation for the portfolio, program, or project manager, given that a single manager is unable to change the culture of an organization. Many managers experience high levels of stress when faced with a no-win prospect. The best way to avoid too much personal stress in these situations is to seek a middle ground—acknowledging the team members’ perceptions about the organization‧s lack of congruence without getting stuck in too much negativity. The manager might say something like:

Like you, I also believe the company may not be walking the talk on this issue. However, I do not want to spend too much time trying to understand where senior management stands on this issue. Instead, I suggest we focus on what we can do on our level to resolve the contradictions in a way that allows us to go forward and feel as positive and productive as we can about the project.

The tone of this message validates the perceptions of the team in a forthright manner but does not slip into company bashing.

To manage personal stress in situations involving an organizational lack of congruence, the portfolio, program, or project manager should be realistic about what can and cannot be done to correct the situation.

Project managers should intently focus the team on what can be done at the team level to resolve the discrepancies and keep the project moving forward in a positive manner.

If working on a program, keep the team focused on the program‧s vision and mission and its importance to the organization.

If you are the portfolio manager, try to focus on why changes are occurring and communicate them as quickly as possible to everyone involved.

Portfolio, program, and project managers can get mired in attempting to right the wrongs of the organization. These managers experience excessive stress if they assume too much personal responsibility for correcting dysfunctional organizational behavior that is beyond their control. Do what you can, but take care that you do not ask too much of yourself.

Stress Caused by the Manager‧s Personal Traits and Habits

A person‧s personality can directly contribute to the level of stress he or she experiences (Table 7-4).

Table 7-4 Personality Traits That Can Increase Personal Stress

Four personality traits that particularly contribute to managers’ stress include perfectionism and time urgency, an overcontrolling approach to work, an unconscious adherence to certain personal myths or beliefs, and excessive multitasking.

Perfectionism and Time Urgency

The portfolio, program, or project manager with perfectionistic tendencies understands on an intellectual level that perfection is not achievable, but this awareness often is not reflected in his or her behavior. A person with a perfectionistic style combined with a sense of time urgency often has the makings of a Type A personality (Friedman 1996).

A portfolio, program, or project manager with perfectionistic qualities and a sense of time urgency may believe that:

There is only one acceptable level of performance.

Anything short of that level of performance will be viewed as a failure.

Work needs to be done as soon as possible, with little consideration of whether it really matters.

The perfectionist manager needs to keep these qualities under control so that they do not cause personal turmoil. Before a task begins, he or she should spend some time listing all expectations—realistic and unrealistic—for his or her own performance and for the result and timing of the project. Keep this list on hand throughout the project and refer to it regularly. Determine whether you are allowing yourself to drift into activities that have little impact on project success.

Overcontrol

An ongoing challenge for a manager is to define the often nebulous point at which exercising appropriate control over a program or project becomes a matter of overcontrol. When not held in check by personal awareness, a tendency toward overcontrol creates stress for the portfolio, program, and project manager. He or she is unable to relax, believing that he or she must remain vigilant to control unseen forces or to avoid problems that have yet to occur.

If you believe that overcontrol may be a personal issue for you as a manager, you can explore that possibility by noting any thoughts that suggest you are trying to take too much responsibility for or control over a situation—for example, “If I do not personally review all of the technical drawings, something big will be missed and we will fail.” After compiling a list of these types of thoughts, ask yourself the following questions:

What would be the worst consequence if this event occurred?

What is the risk of that consequence to the overall portfolio, program, or project?

How bad is that consequence?

How could I manage that consequence?

Could the portfolio, program, or project and I survive if that consequence actually happened?

The process of delineating fears and worst-case scenarios can have a calming effect. Once the manager has explored the negative consequences, he or she can create a survival plan. This process allows the manager to let go of some of the emotionally charged aspects of the situation.

Runaway Personal Myths and Beliefs

All of us have reasons for doing the things we do. Some of these reasons are known to us on a conscious level; other reasons operate on less conscious levels. Many of the reasons we do any task are based on deep, substantive personal myths that we bring with us to the work world.

Personal myths are beliefs that we use to describe ourselves and our motivations in life. Myths are developed in early years and at formative turning points in our lives. For example, a personal myth developed early in life might be: “I am the smartest kid in my class, and I need to show others that I can solve any problem.” Such a personal belief may be grounded initially in fact and then reinforced by teachers, parents, other students, and the world at large.

Personal myths are important because they help motivate us to take action by providing a generalization that we can apply in the workplace. The generalization provides an identity for us—something that tells others, as well as ourselves, who we are. Examples of these identities or personal myths include:

Myths serve a positive purpose when they give us a role or purpose on a team. However, if a myth is operating within us on an unconscious level, we may eventually notice that it has taken control of our behavior and has placed us in stressful situations. Personal myths need to be made conscious. Gaining awareness of our personal myths helps us avoid being managed by them. If we do not have an awareness of what is driving us, we may experience excessive distress, personal pain, and professional problems. How does one become more aware of personal myths? Here is a suggestion.

Imagine you are working on a virtual team. No one else on your team is in your location. You have been promoted in your organization many times in a short period of time and have also obtained your PMP and an advanced degree in project management. You believe, therefore, that you have more knowledge than anyone else on your virtual team. You find that you are constantly asking team members how you can help them, seeking new assignments, asking the project manager how you can work more with various stakeholders, asking to lead team meetings, and taking on the most challenging work packages on the project. But by taking on so many assignments, in addition to your own work, you are creating undue stress for yourself.

Excessive Multitasking

Many people thrive in a multitasking environment. They consider it a success to be able to do two or three things at once, such as using a smartphone or netbook to answer emails during a meeting. This multitasking work style has become so common that some people think it is necessary. Jones, for example, writes, “Project managers obviously can‧t do it alone. They‧re going to need a team of multitasking experts as well” (2009, p. 54).

Although we often do not have the luxury of working on a single assignment, we must approach multitasking carefully because it can become a source of stress as well as a drain on productivity. Shellenbarger (2003) points out that “multitasking creates the illusion of progress by creating busyness while robbing people of time and mental cycles. Humans are not particularly good at switching contexts.” Each time we switch to another task, we lose time because we must then revisit where we were when we last worked on that task, gather required information, and then review it before we can proceed. Therefore, portfolio, program, and project managers can best guide their teams by prioritizing what must be done today or this week and what can wait until later. Of course, they may not be able to work on only the highest-priority task, but at least they can set the majority of their time aside to do so and can increase overall productivity while reducing stress.

Stress-Management Tips for the Portfolio, Program, or Project Manager

Prepare a charter to define your authority and responsibility, and ask your team to prepare a charter for use by the team to empower itself.

For resource assignment and reallocation, use a knowledge, skills, and competency database if available, or ask that one be set up.

Perform detailed planning, beginning with a WBS, and then link each work package (or program package at the program level) to a specific individual or organization.

Focus on the assigned work and limit multitasking. Set up a specific time to answer emails, return phone calls, or talk informally with others.

Keep emphasizing the vision of your program or project to your team and its importance to the organization‧s strategic goals.

Use your organization‧s knowledge management system, if available, for assistance in solving difficult problems, for collaboration with others, and for locating key experts.

Set up discussion forums or blogs for your team.

Ensure that everyone on the team has access to the same type of software for ease of communication.

Continually focus on stakeholder identification and a stakeholder management strategy.

Recognize that risks can be both opportunities and threats and will affect your program or project. Identifying them and developing responses, as well as monitoring and control, should be ongoing throughout the life cycle.

Realize changes are inevitable, establish a process to effectively manage them when they do occur, and communicate the impact of each change and decisions made as a result of each change to your stakeholders.

When problems arise, do not jump to an immediate decision. Take time to consider what has happened and why, as well as how you feel about what has occurred.

Establish a “no surprises” policy for your team and with your sponsor or governance board.

Focus on open communication, and make a sincere effort to involve people as much as possible in the decision-making and conflict-resolution processes.

Summary

Personal demands on portfolio, program, and project managers are numerous and complicated in today‧s fast-paced environment. Stressors have many sources, including organizational issues, the complexities of program and project management, and the manager‧s personal traits.

Managers should work to develop a solid understanding of what their own sources of stress are and must also recognize that what might be stressful for one manager may not be stressful for another.

When creating a personal stress-management action plan, portfolio, program, and project managers must be creative and willing to experiment with different approaches. Develop a personalized approach to stress management that fits your style. Following and continually improving upon a personalized stress-management approach will help you remain vital, excited, and content, even in the face of complex demands and challenges.

Discussion Questions

A project manager operating within a matrix organization encountered significant frustration even before the project got started. This manager discovered that three functional managers were balking at releasing skilled employees to work on the new project. All three functional managers told the project manager that they were understaffed and could not afford to give up good people.

For three weeks, the project leader held meeting after meeting with these functional managers, trying to convince and cajole them into releasing the needed employees. The functional managers’ arguments seemed shallow and incomplete to the project manager. He viewed their actions as obstructionist, not professional, and they all appeared to resist any attempt he made to reason with them.

After four weeks, the project manager realized that his anger was increasing, so much so that he was hoping to avoid seeing these functional managers in the hallways. His sleep was interrupted by recurring worries about what he was going to do if he could not get these three people for his team.

After days of inadequate sleep, he finally appealed to his project sponsor for support—and the three people were assigned to his team. By that time, however, he felt discouraged, fatigued, and unmotivated. And the real work of the project had yet to begin.

What should the project manager have done to address these personal feelings before starting work on the project?

What would you do if you were in such a situation?

In general, what can project managers do to minimize stress while working in a matrix environment?

You just obtained your PgMP and have been a successful program manager in your organization. You were recently assigned to manage a program in a different business unit in your company. You will be leading a virtual team with members located on two continents and in seven different locations. So far, there are four projects in your program.

One project has a major milestone due to its customer in three weeks. Today, the project manager told you that he is concerned that he cannot meet the deadline. This is particularly problematic because this project has dependencies with two other projects. The project manager told you that a critical subject matter expert (SME) recently quit the company abruptly without giving any notice; another key SME is ill and is not expected to be able to return to work for another month; and a vendor, who is responsible for a major part of the deliverable, is waiting for new technology to be installed.

You know that no one on your team has the same skills as the two SMEs who are no longer available, but you think that another part of the business unit may have resources you could use. You are new to this organization, though, and you are not certain. You also think that you might be able to find another vendor if you could get a meeting set up with your contracts department and review the qualified seller list.

As the program manager, what would you do if you were in this situation?

What should you have done when the program was established to avoid such a situation from occurring in the first place?

What stress-management approaches might you use to reduce this stress that would work for you?