How Accounting Works

In This Chapter

![]()

- Demystifying accounting terms and concepts

- Visualizing the accounting process with T accounts

- Examples of typical accounting transactions

Every profession has its own seemingly cryptic vocabulary and ground rules, and accounting is no different. Almost every business owner needs to know the fundamentals of accounting in order to make sound business decisions, so in this chapter, we start by providing translations for the most important terms and concepts in accounting, laying the foundation for what you learn in later chapters.

Accounting is a means of keeping score within your business, but unlike a lopsided baseball game, the numbers that represent the score for your business must balance.

A common formula that represents both elements is assets – liabilities = equity. As you’ll read later in this book, assets are items your business owns, while liabilities are amounts you owe to others. What’s left over is sometimes referred to as capital, equity, or the net worth of a business. Every transaction that affects your books affects the A – L = E formula. The components of this formula are represented on a report known as a balance sheet. Simply put, it’s the scorecard for what you own, what you owe, and your financial stake in the business.

Here’s another way to think of it: you might have a $100 bill in your pocket; that’s an asset. You owe your friend $20 for lunch; that’s a liability. So you have equity (capital) of $80. However, your brother owes you $10, so your total assets are $110 and your net equity is $90.

Accounting transactions themselves are broken down into a series of debits and credits. Don’t panic if this sounds like a foreign language to you, as we’ll be walking you through all the ins and outs, as well as sharing a helpful tool known as T accounts. T accounts help you visually break down an accounting transaction into the various components that affect your accounting records, or your books. Once you can fit the transaction into T account format, you’re ready to record the transaction in your books.

We also provide an overview of some typical accounting transactions you’ll encounter, with much more detail to follow later in the book.

Accounting Terminology and Concepts

The fundamental aspects of accounting, called principals, have been developed over a series of centuries. Any accounting work you do for your business is not solely for your own benefit. As you’ll see later in the book, even if you’re the sole owner of your business, you’re far from the sole stakeholder. Lenders, tax agencies, customers, vendors, employees—all have an interest in your success.

Accounting conventions ensure everyone’s books are kept in the same fashion. This enables governmental agencies to compare your books to similar businesses to decide if your financial results make sense. The structure also gives you a clear understanding of what your business owns, what it owes, and what capital it has that can be distributed to you or reinvested into your business.

There’s a cause-and-effect aspect to accounting. If you buy pizza for a staff meeting, the cause is you’ve boosted employee morale, but the effect is you’ve reduced your cash on hand and recorded an expense on your books. It’s important to understand that there are at least two sides to every accounting transaction. Your pizza purchase increased an expense and reduced your cash account.

It’s not always one account goes up and another goes down, though. Let’s say a customer pays you for a service. In this case, your cash account goes up and your sales go up as well.

Figuring it all out can feel bewildering at first, but as you gain an understanding of the structure of accounting, concepts that might feel like a constraint actually help you ensure you’re correctly tracking the financial aspects of your business.

Books and Accounts

A big part of accounting is keeping a historical record of your transactions. Accountants often refer to this as the books for a business, a term left over from when those books were actual books. Today, the books typically appear on your computer screen.

Most of your accounting transactions record money changing hands between your business and other parties. Later we also discuss some noncash transactions that are important to your business.

The most basic element of accounting is accounts. Accounts are the various categories that describe the types of financial activity that exist in your business.

DEFINITION

In this context, books refers to a set of accounting records. And we’ll get into the specifics of accounts later in this book, but for now, think of them as buckets in which you store the value of things you own or owe as well as things you’ve earned or spent money on.

Some accounts are for tracking what you own or are owed. For instance, a cash account reflects how much money you have in the bank. Other accounts reflect what you’ve earned or spent. If you’re in the pet boarding business, for example, you might have one or more revenue accounts that keep track of the boarding fees your customers have paid you. You also might have multiple expense accounts to keep track of pet-related expenses such as pet food, waste disposal, and veterinarian fees. Each one of these items is a separate account. If you’re in the catering business, you might have expense accounts for food, serving dishes, cookbooks, and so on.

Debits and Credits

Accounting uses a standard double-entry system in which the sum total of debits and credits balance each other. For example, writing a check to a supplier might result in several debits to different expense accounts and one credit to reduce the balance of your cash account. Every transaction you record to your accounting records has to balance.

DEFINITION

A traditional accounting ledger has at least four columns: date, description, and two amount columns. This double-entry system requires that the entries or amounts in each column balance each other. Debits are amounts that appear in the left amount column and record changes in value. Depending on context, they might increase or decrease the value of an account. Credits also record changes in value and typically appear in the right column of an accounting ledger. Credits might also increase or decrease the value of an account. Beginning accounting students are often taught “Debits on the left; credits on the right.”

Why the need for balance? Because every normal business transaction affects both the balance sheet and income statement. A cash sale, for example, increases Cash (a balance sheet account) and increases Sales (an income statement account) in equal amounts.

To help you wrap your head around this debits and credits concept, imagine you need some paperclips and a couple binders. You head over to the office supply store and purchase $10 worth of office supplies. Your Office Supplies account now has a value of $10, the amount you spent. To balance that $10, your Cash account now has a value of $10 less than whatever it was before you went to the store.

Assets and Liabilities

Much of the confusion people have with accounting can be attributed to their monthly bank statement. You’ll see accounting transactions that debit your account for checks, ATM withdrawals, and fees along with credits that reflect deposits and transfers into your account. The problem comes in when, on your accounting records, you record the mirror image of these transactions.

Let’s look at an example:

- You receive payment from a customer. In your accounting records, you debit (increase) your Cash account and credit (another increase) your Revenue account.

- You take the check to the bank to deposit it. Your banker credits your checking or savings account (an increase) and debits the bank’s Cash account (another increase).

In your books, your Cash account is an asset. In your banker’s books, that same account that contains your money is a liability. In other words, you’re simply allowing the bank to hold your money temporarily; technically, the bank owes you that money.

DEFINITION

From a financial accounting perspective, assets are items of value your business owns or is owed, such as cash, Accounts Receivable (unpaid customer invoices), inventory, vehicles, real estate, etc. A liability is an amount you owe to others. This could be unpaid bills (Accounts Payable), payroll taxes, sales tax you’ve collected and owe the state government, bank loans, mortgages, etc.

The source of so much confusion in your initial exposure to accounting is your bank reporting, “Here’s what we did on our books,” which is the exact mirror image of how you record transactions on your books for your business.

T Accounts

A T account isn’t a type of account in your books, but rather a device you use for visualizing how to record an accounting transaction. You won’t use T accounts very often, but they can come in handy.

As mentioned earlier, accounting primarily centers around two amount columns, debits on the left and credits on the right, and the sum of both columns has to match. If you’re trying to figure out how to record a transaction, T accounts can help.

How T Accounts Work

To explain T accounts, let’s first take a look at a simple example of how they work. Say you receive $100 as a payment from a customer. You increase Cash (it’s a debit, by the way) by $100, and increase Revenue (a credit) by $100. Your T account for Cash shows $100 on the left in the debit column. (Cash is an asset, and increases to asset accounts are debits. We discuss this more later.)

Now you need a T account that balances this debit with a credit (right column). The T account for your Revenue shows $100 on the right. (Revenue accounts are increased with credits.) You’ve got $100 on the left and $100 on the right in your two T accounts, so they’re in balance.

The $100 debit in the Cash T account balances the $100 credit in the Revenue T account.

Using T Accounts

Let’s look at some more typical examples of how T accounts help you determine how to record a transaction, particularly when more than two accounts are involved. For purposes of these transactions, let’s assume you’re using accounting software and not writing down each transaction in a traditional ledger book. (See Chapter 3 for more information on accounting software options.)

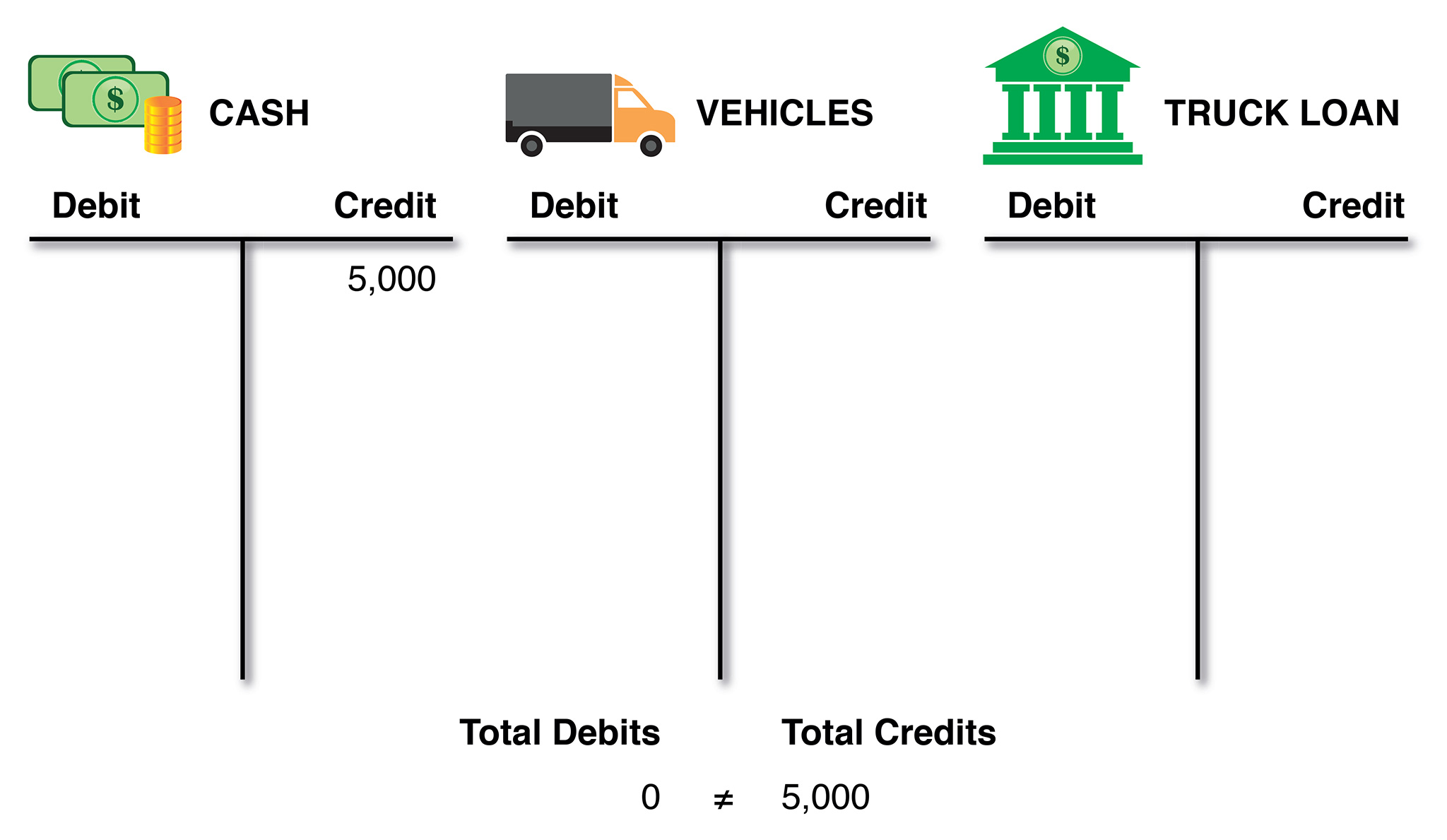

Say you finance the purchase of a delivery truck for your business. This seemingly simple transaction touches multiple accounts on your books. Your truck costs $30,000, and you make a $5,000 down payment. When updating your books, you need to record that you used some of your cash, that you now own a truck, and that you also owe $25,000 on it. But what do you debit, and what do you credit? That’s where T accounts cut through the confusion.

You need to record changes to three accounts:

- Your Cash account (in accounting vernacular, an asset account because we own the cash)

- A Vehicles account (another asset account because your business owns the truck)

- A Loan account (a liability account because your business owes the loan amount)

So you need three T accounts, Cash, Vehicles, and Truck Loan. On a blank piece of paper, draw your three T accounts, making them large enough you can write numbers on either side of the T.

T accounts provide a framework you can use to break down an accounting transaction into its elements and ensure your debits and credits balance.

BOTTOM LINE

Taking the time to write out T accounts helps ensure you enter the transaction correctly in your accounting software. Remember that the sum of all amounts written on the left side of a T must balance with the amounts written on the right side of another T. Each T represents a separate account in your books or accounting software.

Now that you have your framework, you can begin to record the purchase. Debits (left-side entries) always increase asset accounts and reduce liability accounts, while credits (right-side entries) reduce asset accounts and increase liability accounts.

Here’s how to record your transaction:

1. You wrote a check for $5,000, which reduced your Cash account. Write 5,000 in the right Credit column of the Cash T account.

Increases to the Cash account go on the left side of the T; decreases go on the right.

2. Your business now owns a $30,000 delivery truck, which is an increase in assets. Write 30,000 in the left Debit column of the Vehicles T.

Increases to the Vehicles account go on the left side of the T; decreases go on the right.

3. You know the sum of your debits and credits must match at the end, but so far, you have a $30,000 debit and a $5,000 credit. You still need to record a $25,000 credit to get the transaction to balance. The last piece of your transaction is to record the $25,000 your business borrowed to purchase the truck. Enter that amount on the right side of the Truck Loan T.

Increases to the Truck Loan account go on the right side of the T; decreases go on the left.

At this point, the sum of your debits and credits match. Remember, debits and credits aren’t one-for-one. In this case, we have two credits and one debit, but in total, the three amounts balance.

Using T accounts, you’ve figured out where everything goes, so you can record this transaction in your accounting software.

Recording Your Transaction

Often your transactions are recorded when you fill out forms like invoices or bills, and your software puts those transaction amounts into the correct accounts.

You also can enter a transaction directly into the accounts through a journal entry. With a journal entry, you enter the amounts associated with a transaction directly into the accounts instead of using an entry form like an invoice. You likely won’t have to enter journal entries very often into your accounting software. Most transactions are handled by other input screens, and many businesses let their outside accountants take care of any necessary journal entries.

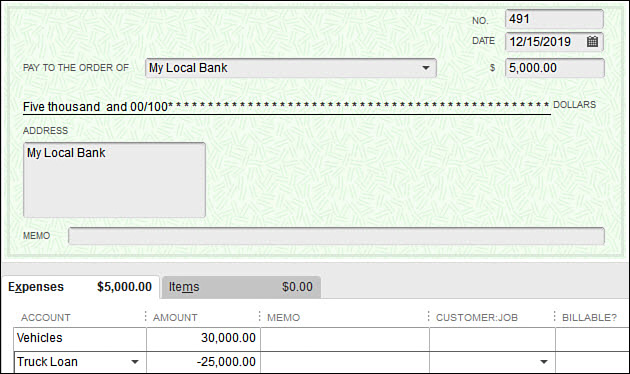

But let’s assume the bank withdrew $5,000 from your account as part of the loan closing process, so you don’t have an actual check to record. You can record this transaction in your books in one of two ways, as a check or as a journal entry.

Check: Even if you don’t physically write or print a check, you can still use the check screen in your accounting software to record a cash transaction. In this case, the transaction has two lines. You increase the Vehicles account by $30,000 and record the Truck Loan as a negative $25,000. The net $5,000 remaining reduces the Cash account because this transaction is a check.

Recording a transaction as a check.

Journal entry: Alternatively, you can record a journal entry. Although it’s not required, journal entries typically record changes in cash first, followed by changes in assets, liabilities, equity, income, and expenses, respectively.

Recording a transaction as a journal entry.

ACCOUNTING HACK

Anything can be repaired in your accounting records, so don’t overanalyze how to record transactions. If you’re not sure exactly how to record something, take your best shot at it, and we’ll show you how to clean it up later. It’s far better to have the transaction recorded in some fashion in your books, even if it’s temporarily not posted correctly. Don’t put off logging transactions just because you’re not sure how to do it. That could lead to much unnecessary grief and potentially cost your company money.

Typical Accounting Transactions

Throughout this chapter, we’ve mentioned debits and credits, but for most projects, you won’t have to concern yourself with this level of detail. Most of the time when you perform accounting tasks, you’re filling in blanks in the accounting software screens and letting it take care of the debiting and crediting.

Let’s look at some sample transactions.

Checks

You’ll have the option to handwrite checks when you pay your bills, or you can print checks directly onto blank check stock from your accounting software. No matter how you generate the payment, you’ll record it as a check in your accounting software.

Let’s assume the pet boarding business mentioned earlier has received a $1,000 shipment of dog food from a local vendor. Depending on how the business plans to use the food, the transaction might get entered one of two different ways:

As a check to record pet food expense: If the pet boarding business doesn’t sell food to customers but only uses the food to feed pets in its care, this purchase is considered an operating expense. This means the purchase would reduce the Cash account by $1,000 and increase the Pet Food Expense account by $1,000.

As a check to record pet food that customers buy to take home: If the business plans to sell the food to its customers, the initial purchase isn’t considered an expense, but rather a purchase of inventory. Remember, inventory is an asset, so the business has traded one asset, cash, for another asset, pet food to be sold at a profit. In this case, the purchase reduces the Cash account by $1,000 and increases the Pet Food Inventory account by $1,000. Later, when customers purchase the pet food, an invoice transaction increases the Cash account and increases the Revenue account.

Note that in addition to recording the sale and the application of the cash, something else is happening in the background. You’ve sold pet food, so you’ve reduced your Pet Food Inventory account. Your software reduces the Inventory account and increases a Cost of Goods Sold account. It automatically makes these transfers for you, so you can focus just on the sale itself and not worry about accounting for inventory.

Accounting is a unique discipline in that the intent of the business’s use of the transaction often determines the category (account) used. In one case, it was operating expense, and in another, it was inventory.

Depending on the nature of your business, you might provide goods or services to the customer in advance of receiving payment. In such situations, you’ll record an invoice in your accounting software so you can keep track of the amounts due to you. These invoices can take a variety of forms, but let’s look at a simple example.

Say your teenager provides lawn-mowing services for some of your neighbors. Your teen could try to collect payment each time he mows a yard, or he might invoice customers either after each mowing or perhaps in advance. In this case, the invoice transaction would look something like the following figure.

An invoice increases the revenue account, Mowing Services.

It’s easy to see that Mowing Services, an income or revenue account, is being increased by $100. But behind the scenes, Accounts Receivable, an asset account, also is being increased by $100. If we were using T accounts to record this, increases in Accounts Receivable appear on the left side of the T, while increases in revenue appear on the right side of the Moving Services T.

At a later date, the customer will pay the invoice, which will result in a transaction to record the payment. This transaction will increase cash by $100 and reduce Accounts Receivable by $100.

BOTTOM LINE

Any amounts in an Accounts Receivable account should only reside there temporarily. Ideally, they’ll be moved to cash when the invoice is paid.

Let’s say your business is selling Popsicles from a cart. Customers pay you on the spot for their purchase, so there’s no need to record an invoice and then a payment against it. Instead, you record a special type of transaction known as a sales receipt.

Sales of Popsicles affect your Cash account and your Income accounts. Other accounts can be affected as well, such as an Inventory or Cost of Sales account. However, the one account that won’t be affected by a sales receipt is Accounts Receivable. Remember, Accounts Receivable is intended to be a holding bucket for unpaid transactions. By its very nature, a sales receipt implies that the purchase has been paid for on the spot.

Some transactions trigger a dual entry. The entry to lower inventory and the expense the cost of the Popsicle sold is an example of this. The selling of Inventory items almost always results in this dual-entry requirement, and both are required.

Credit Card Transactions

A good way to think of purchases you make with a credit card is as the inverse of a customer invoice. In this case, you’re the customer of the credit card company, borrowing money today for a purchase you pay for later.

When you make a credit card purchase, you have an increase in a liability account. The offset of a credit card purchase could be many things:

- An expense, such as Telephone Expense for a cell phone bill or, returning to our pet boarding business, a Pet Food Expense.

- An asset account, such as Inventory, when you purchase inventory for your business with a credit card instead of writing a check.

- An insurance account, such as when you pay your monthly premium for a policy.

Record credit card transactions in much the same fashion as you write checks, but instead of reducing your bank account, you temporarily increase your credit card account in your books. When you pay the credit card, either in part or in full, you reduce both your Cash account and the credit card balance. You also might increase an Interest Expense account if interest has accrued on your unpaid balance.

ACCOUNTING HACK

Create a separate account in your accounting records for each credit card you hold.

Recording Estimates and Sales Orders

Not every type of transaction actually affects your books. Let’s say a customer is considering your services. The accounting software you use might enable you to create an estimate. This transaction looks very much like an invoice, and it might reference accounts on your chart of accounts. However, an estimate is simply a reference transaction and won’t actually increase or decrease any accounts in your books.

When your customer agrees to the work, the accounting software allows you to convert the estimate into an invoice.

Invoices do affect your books, increasing your Accounts Receivable account and typically increasing one or more Income accounts.

Here’s another example: assume your business sells parts for earthmoving equipment. A customer places an order for several teeth for his bulldozer, but you don’t currently have them in stock. Some accounting software programs allow you to create sales orders, which are similar to estimates. The distinction is the word order.

With a sales order, you’ve a confirmed purchase you’ll eventually deliver. But because you haven’t provided the items in question yet, this isn’t actually an invoice. Your accounting software enables to you ship all or part of the order, at which point an invoice is created for each segment of the order you deliver.

The Least You Need to Know

- Accounting can be thought of as a simple method of scorekeeping for your business.

- T accounts help you map out which accounts are debited and which are credited.

- The debits and credits created in various types of transactions you make always balance each other.

- Recording check, invoice, sales receipt, credit card transaction, estimate, and sales order transactions isn’t difficult, and your accounting software handles much of the behind-the-scenes details.