Putting your faith in experts

Letting your emotions guide your investment decisions

Giving up when the market takes a plunge

Ignoring your financial big picture

Just as with raising children or in one's career, "success" with personal investing is in the eye of the beholder. In my work as a financial counselor, instructor, and writer, I've come to define a successful investor as someone who, with a modest commitment of time, develops an investment plan to accomplish financial and personal goals and earns returns commensurate with the risk he's willing to accept.

In this chapter, I point out ten common obstacles that may keep you from fully realizing your financial goals and share tips and advice for overcoming those obstacles on the road to investing success.

Some investors assume that an advisor is competent and ethical if she has a lofty title (financial consultant, vice president, and so on), dresses well, and works in a snazzy office. Such accessories are often indicators of salespeople — not objective advisors — who recommend investments that will earn them big commissions that come out of your investment dollars.

Additionally, if you overtrust an advisor, you may not research and monitor your investments as carefully as you should. Figuring that Mr. Vice President is an expert, some investors go along without ever questioning his advice or watching what's going on with their investments.

You should also question authority elsewhere in the investment business. Too many investors blindly follow analysts' stock recommendations without considering the many conflicts of interest that such brokerage firm employees have. Brokerage analysts are often cheerleaders for buying various companies' stock because their firms are courting the business of new stock and bond issuance of the same companies. And just because a big-name accounting firm has blessed a company's financial statements (Enron) or a company's CEO says everything is fine (Bear Stearns) doesn't make a firm's financial statements accurate or its conditions sound.

Tip

You can't possibly evaluate the competence and agenda of someone you hire until you understand the lay of the land. You can't possibly know for sure that an analyst's report or a professional service firm's recommendation or approval of a company is worth the paper it's printed upon. Read good publications (see Part V) on the topic to master the jargon and figure out how to evaluate investments. Seek independent second opinions before you act on someone's recommendations. If you're in the market for a broker, be sure to read Chapter 9.

Feeling strength and safety in numbers, some investors are lured into buying hot stocks and sectors (for example, industries like technology, health care, biotechnology, retail, and so on) after major price increases. Psychologically, it's reassuring to buy into something that's going up and gaining accolades. The obvious danger with this practice is buying into investments selling at inflated prices that too soon deflate.

In the U.S. stock market by the late 1990s, investors were getting spoiled with gains year after year in excess of the historic average annual return of 9 to 10 percent. Numerous surveys conducted during this period showed that many investors expected to earn returns in the range of 15 to 20 percent annually, nearly double the historic average. As always happens, though, after a period of excessively high returns such as those of the 1990s, returns were below average in the subsequent period beginning in 2000 (and were quite negative in the early 2000s). During the market slump in the early 2000s, real estate-related stocks continued to do well; some folks mistakenly believed that the housing sector was immune to setbacks and were surprised by the slump in that sector in the late 2000s.

Tip

Develop an overall allocation among various investments (especially diversified mutual funds), and don't make knee-jerk decisions to change your allocation based upon what the latest hot sectors are. If anything, de-emphasize or avoid stocks and sectors that are at the top of the performance charts. Think back to the last time you went bargain shopping for a consumer item — you looked for value, not high prices. See Chapter 5 to find out how to spot good values in the financial markets and speculative bubbles to avoid.

As I discuss in Part V, newsletters, books, and even some financial periodicals lead investors to believe that you can be the next Peter Lynch or Warren Buffett if you follow a simple stock-picking system. The advent of the Internet and online trading capabilities has spawned a whole new generation of short-term (sometimes even same-day) traders.

In my work as a financial counselor, I came across plenty of people who lost a lot of money after they had an early winner and had attributed that success to their investing genius. These folks usually landed on my doorstep after great and humbling losses woke them up.

Tip

If you have the speculative bug, earmark a small portion of your portfolio (no more than 10 to 20 percent) for more aggressive investments. See Chapter 5 for more information on questions to help you decide whether you or someone you know has a gambling problem.

Inexperienced or nervous investors may be tempted to bail out when it appears that an investment isn't always profitable and enjoyable. Some investors dump falling investments precisely at the times when they should be doing the reverse — buying more. Whenever the U.S. stock market drops more than a few percentage points in a short period, it attracts a lot of attention, which then leads to concern, anxiety, and in some cases, panic. Corrections in excess of 10 percent, such as happened in late 2007 and early 2008, lead to all sorts of hand wringing and gloom-and-doom talk.

Investing always involves uncertainty. Many people forget this, especially during good economic times. I find that investors are more likely to feel more comfortable with riskier investments, such as stocks, when they recognize that all investments carry uncertainty and risk — just in different forms.

Note

History has repeatedly proved that continuing to buy stocks during down markets increases your long-term returns. The worst thing you can do in a slumping market is to throw in the towel.

Unfortunately, the short-term focus that the media so often takes causes some investors to worry that their investments are in shambles during the inevitable bumps in the road. As I discuss in Part V, the media are often to blame because they hype short-term events and blow those events out of proportion to captivate viewers and listeners. History has shown that financial markets recover; recovery is just a question of time. If you invest for the long term, then the last six weeks — or even the last couple of years — is a short period. Plus, countless studies demonstrate that no one can predict the future, so you gain little from trying to base your investment plans on predictions. In fact, you can lose more money by trying to time the markets.

Larger-than-normal market declines hold a significant danger for investors: They may encourage decision making that's based on emotion rather than logic. Just ask anyone who sold after the stock market collapsed in 1987 — the U.S. stock market dropped 35 percent in a matter of weeks in the fall of that year. Since then, even with the significant declines in the early 2000s, the U.S. market has risen more than sevenfold!

Tip

Investors who can't withstand the volatility of riskier growth-oriented investments, such as stocks, may be better off not investing in such vehicles to begin with. Examining your returns over longer periods helps you keep the proper perspective. If a short-term downdraft in your investments depresses you, avoid tracking your investment values closely. Also, consider investing in highly diversified, less-volatile funds that hold stocks worldwide as well as bonds (see Chapter 8).

Although some investors realize that they can't withstand losses and sell at the first signs of trouble, other investors find that selling a losing investment is so painful and unpleasant that they continue to hold a poorly performing investment, despite the investment's poor future prospects. Psychological research backs this up — people find the pain of accepting a given loss twice as intense as the pleasure of accepting a gain of equal magnitude.

Tip

Analyze your lagging investments to identify why they perform poorly. If a given investment is down because similar ones are also in decline, hold on to it. However, if something is inherently wrong with the investment — such as high fees or poor management — make taking the loss more palatable by remembering two things:

If your investment is a non-retirement account investment, selling at a loss helps reduce your income taxes.

Consider the "opportunity cost" of continuing to keep your money in a lousy investment — that is, what returns can you get in the future if you switch to a "better" investment?

The investment world seems so risky and fraught with pitfalls that some people believe that closely watching an investment can help alert them to impending danger. "The constant tracking is not unlike the attempt to relieve anxiety by fingering worry beads. Yet paradoxically, it can increase emotional distress because it requires a constant state of vigilance," says psychologist Dr. Paul Minsky.

In my work as a financial counselor, I see that investors who are the most anxious about their investments and most likely to make impulsive trading decisions are the ones who watch their holdings too closely, especially those who monitor prices daily. The proliferation of Internet sites and stock market cable television programs offering up-to-the-minute quotations gives these investors even more temptation to overmonitor investments.

Tip

Restrict your "diet" of financial information and advice. Quality is far more important than quantity. Watching the daily price gyrations of investments is akin to eating too much junk food — doing so may satisfy your short-term cravings but at the cost of your long-term health. If you invest in diversified mutual funds (see Chapter 8), you really don't need to examine your fund's performance more than once or twice per year. An ideal time to review your funds is when you receive their annual or semiannual reports. Although many investors track their funds daily or weekly, far fewer read their annual reports. Reading these reports can help you keep a long-term perspective and gain some understanding as to why your funds perform as they do and how they compare to major market averages.

Investing is more complicated than simply setting your financial goals (see Chapter 3) and choosing solid investments to help you achieve them. Awareness and understanding of the less tangible issues can maximize your chances for investing success.

Tip

In addition to considering your goals in a traditional sense (when you want to retire, how much of your kids' college costs you want to pay) before you invest, you should also consider what you want and don't want to get from the investment process. Do you treat investing as a hobby or simply as another one of life's tasks, such as maintaining your home? Do you enjoy the intellectual challenge of picking your own stocks? Don't just ponder these questions on your own; discuss them with family members, too — after all, you're all going to have to live with your decisions and investment results.

I know plenty of high-income earners, including more than a few who earn six figures annually, who have little to invest. Some of these people have high-interest debt outstanding on credit cards and auto loans, yet they spend endless hours researching and tracking investments.

I also know many people who built significant personal wealth despite having modest-paying jobs. The difference: the ability to live within your means.

If you don't earn a high income, you may be tempted to think that you can't save. Even if you are a high-income earner, you may think that you can hit an investment home run to accomplish your goals or that you can save more if you can bump up your income. This way of thinking justifies spending most of what you earn and saving little now. Investing is far more exciting than examining your spending and making cutbacks. If you need help coming up with more money to invest, see the latest edition of my book Personal Finance For Dummies (published by Wiley).

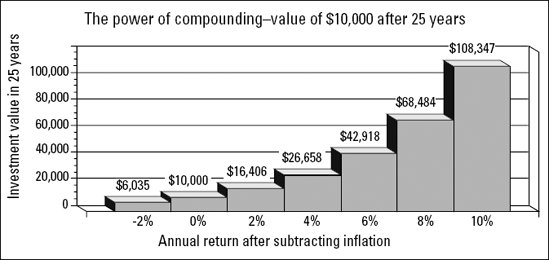

Saving money is only half the battle. The other half is making your money grow. Over long time periods, earning just a few percent more makes a big difference in the size of your nest egg. Earning inflation-beating returns is easy to do if you're willing to invest in stocks, real estate, and small businesses. Figure 20-1 shows you how much more money you'll have in 25 years if you can earn investment returns that are greater than the rate of inflation (which is currently running at about 3 percent).

As I discuss in Chapter 2, ownership investments (stocks, real estate, and small business) have historically generated returns greater than the inflation rate by 6 percent or more, while lending investments (savings accounts and bonds) tend to generate returns of only 1 to 2 percent above inflation. However, some investors keep too much of their money in lending investments out of fear of holding an investment that can fall greatly in value. Although ownership investments can plunge in value, you need to keep in mind that inflation and taxes eat away at your lending investment balances.

Stock market declines, like earthquakes, bring all sorts of prognosticators, soothsayers, and self-anointed gurus out of the woodwork, particularly among those in the investment community, such as newsletter writers, who have something to sell. The words may vary, but the underlying message doesn't: "If you had been following my sage advice, you'd be much better off now."

Warning

People spend far too much of their precious time and money in pursuit of a guru who can tell them when and what to buy and sell. Peter Lynch, the former manager of the Fidelity Magellan Fund, amassed one of the best long-term stock market investing track records. His stock-picking ability allowed him to beat the market averages by just a few percent per year. However, even he says that you can't time the markets, and he acknowledges knowing many pundits who have correctly predicted the future course of the stock market "once in a row"!

Clearly, in the world of investing, the most successful investors earn much better returns than the worst ones. But what may surprise you is that you can end up much closer to the top of the investing performance heap than the bottom if you follow some relatively simple rules, such as regularly saving and investing in low-cost growth investments. In fact, by doing so you can beat many of the full-time investment professionals.