Chapter 5

Building Wealth with Stocks

In This Chapter

![]() Getting to know stock markets and indexes

Getting to know stock markets and indexes

![]() Buying stocks the smart way

Buying stocks the smart way

![]() Understanding the importance of price-earnings ratios

Understanding the importance of price-earnings ratios

![]() Learning from past bubbles and periods of pessimism

Learning from past bubbles and periods of pessimism

![]() Sidestepping common stock-shopping mistakes

Sidestepping common stock-shopping mistakes

![]() Taking steps to improve your chance of success in the market

Taking steps to improve your chance of success in the market

Some people liken investing in the stock market to gambling. A real casino structures its games — such as slot machines, blackjack, and roulette — so that in aggregate, the casino owners siphon off a major chunk (40 percent) of the money that people gamble with. The vast majority of casino patrons lose money, in some cases all of it. The few who leave with more money than they came with are usually people who are lucky and are smart enough to quit while they’re ahead.

I can understand why some individual investors feel that the stock market resembles legalized gambling. Fortunately, the stock market isn’t a casino — it’s far from it. Shares of stock, which represent portions of ownership in companies, offer a way for people of modest and wealthy means, and everybody in between, to invest in companies and build wealth. History shows that long-term investors can win in the stock market because it appreciates over the years. That said, some people who remain active in the market over many years manage to lose some money because of easily avoidable mistakes, which I can keep you from making in the future. This chapter gets you up to speed on successful stock market investing.

Taking Stock of How You Make Money

- Dividends: Most stocks pay dividends. Companies generally make some profits during the year. Some high-growth companies reinvest most or all of their profits right back into the business. Many companies, however, pay out some of their profits to shareholders in the form of quarterly dividends.

- Appreciation: When the price per share of your stock rises to a level greater than you originally paid for it, you make money. This profit, however, is only on paper until you sell the stock, at which time you realize a capital gain. (Such gains realized over periods longer than one year are taxed at the lower long-term capital gains tax rate; see Chapter 3.) Of course, the stock price per share can fall below what you originally paid as well (in which case you have a loss on paper unless you realize that loss by selling).

If you add together dividends and appreciation, you arrive at your total return. Stocks differ in the dimensions of these possible returns, particularly with respect to dividends.

Defining “The Market”

You invest in stocks to share in the rewards of capitalistic economies. When you invest in stocks, you do so through the stock market. What is the stock market? Everybody talks about “The Market” the same way they do the largest city nearby (“The City”):

- The Market is down 137 points today.

- With The Market hitting new highs, isn’t now a bad time to invest?

- The Market seems ready for a fall.

When people talk about The Market, they’re usually referring to the U.S. stock market. Even more specifically, they’re usually speaking about the Dow Jones Industrial Average, created by Charles Dow and Eddie Jones, which is a widely watched index or measure of the performance of the U.S. stock market. Dow and Jones, two reporters in their 30s, started publishing a paper that you may have heard of — The Wall Street Journal — in 1889. Like the modern-day version, the 19th-century Wall Street Journal reported current financial news. Dow and Jones also compiled stock prices of larger, important companies and created and calculated indexes to track the performance of the U.S. stock market.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (“the Dow”) market index tracks the performance of 30 large companies that are headquartered in the United States. The Dow 30 includes companies such as telecommunications giant Verizon Communications; airplane manufacturer Boeing; beverage maker Coca-Cola; oil giant Exxon Mobil; technology behemoths IBM, Intel, and Microsoft; drug makers Merck and Pfizer; fast-food king McDonald’s; and retailers Home Depot and Wal-Mart.

Some criticize the Dow index for encompassing so few companies and for a lack of diversity. The 30 stocks that make up the Dow aren’t the 30 largest or the 30 best companies in America. They just so happen to be the 30 companies that senior staff members at The Wall Street Journal think reflect the diversity of the economy in the United States (although utility and transportation stocks are excluded and tracked in other Dow indexes). The 30 stocks in the Dow change over time as companies merge, decline, and rise in importance.

Looking at major stock market indexes

Just as New York City isn’t the only city to visit or live in, the 30 stocks in the Dow Jones Industrial Average are far from representative of all the different types of stocks that you can invest in. Here are some other important market indexes and the types of stocks they track:

- Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500: Like the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the S&P 500 tracks the price of 500 larger-company U.S. stocks. These 500 big companies account for more than 70 percent of the total market value of the tens of thousands of stocks traded in the United States. Thus, the S&P 500 is a much broader and more representative index of the larger-company stocks in the United States than the Dow Jones Industrial Average is.

Unlike the Dow index, which is primarily calculated by adding the current share price of each of its component stocks, the S&P 500 index is calculated by adding the total market value (capitalization) of its component stocks.

Unlike the Dow index, which is primarily calculated by adding the current share price of each of its component stocks, the S&P 500 index is calculated by adding the total market value (capitalization) of its component stocks. - Russell 2000: This index tracks the market value of 2,000 smaller U.S. company stocks of various industries. Although small-company stocks tend to move in tandem with larger-company stocks over the longer term, it’s not unusual for one to rise or fall more than the other or for one index to fall while the other rises in a given year. For example, in 2001, the Russell 2000 actually rose 2.5 percent while the S&P 500 fell 11.9 percent. In 2007, the Russell 2000 lost 1.6 percent versus a gain of 5.5 percent for the S&P 500. Be aware that smaller-company stocks tend to be more volatile. (I discuss the risks and returns in more detail in Chapter 2.)

- Wilshire 5000: Despite its name, the Wilshire 5000 index actually tracks the prices of more than 5,000 stocks of U.S. companies of all sizes — small, medium, and large. Thus, many consider this index the broadest and most representative of the overall U.S. stock market.

- MSCI EAFE: Stocks don’t exist only in the United States. MSCI’s EAFE index tracks the prices of stocks in the other major developed countries of the world. EAFE stands for Europe, Australasia, and Far East.

- MSCI Emerging Markets: This index follows the value of stocks in the less economically developed but “emerging” countries, such as Brazil, China, Russia, Taiwan, India, South Africa, Chile, Mexico, and so on. These stock markets tend to be more volatile than those in established economies. During good economic times, emerging markets usually reward investors with higher returns, but stocks can fall farther and faster than stocks in developed markets.

Counting reasons to use indexes

Indexes serve several purposes. First, they can quickly give you an idea of how particular types of stocks perform in comparison with other types of stocks. In 1998, for example, the S&P 500 was up 28.6 percent, whereas the small-company Russell 2000 index was down 2.5 percent. That same year, the MSCI foreign stock EAFE index rose 20.3 percent. In 2001, by contrast, the S&P 500 fell 11.9 percent, and the EAFE foreign stock index had an even worse year, falling 21.4 percent. In 2013, the S&P 500 surged 29.7 percent while the foreign EAFE index returned 18 percent.

Indexes also allow you to compare or benchmark the performance of your stock market investments. If you invest primarily in large-company U.S. stocks, for example, you should compare the overall return of the stocks in your portfolio to a comparable index — in this case, the S&P 500. (As I discuss in Chapter 8, index mutual funds, which invest to match a major stock market index, offer a cost-effective, proven way to build wealth by investing in stocks.)

You may also hear about some other types of more narrowly focused indexes, including those that track the performance of stocks in particular industries, such as advertising, banking, computers, pharmaceuticals, restaurants, semiconductors, textiles, and utilities. Other indexes cover the stock markets of other countries, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Canada, and Hong Kong.

Stock-Buying Methods

When you invest in stocks, many (perhaps too many) choices exist. Besides the tens of thousands of stocks from which you can select, you also can invest in mutual funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), or hedge funds, or you can have a stockbroker select for you.

Buying stocks via mutual funds and exchange-traded funds

If you’re busy and suffer no delusions about your expertise, you’ll love the best stock mutual funds. Investing in stocks through mutual funds can be as simple as dialing a toll-free phone number or logging on to a fund company’s website, completing some application forms, and zapping them some money.

Mutual funds take money invested by people like you and me and pool it in a single investment portfolio in securities, such as stocks and bonds. The portfolio is then professionally managed. Stock mutual funds, as the name suggests, invest primarily or exclusively in stocks (some stock funds sometimes invest a bit in other stuff, such as bonds).

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are the new kid on the block, certainly in comparison to mutual funds. ETFs are in many ways similar to mutual funds, specifically index funds (see Chapter 8), except that they trade on a stock exchange. One potential attraction is that some ETFs offer investors the potential for even lower operating expenses than comparable mutual funds and may be tax-friendlier. I expand on ETFs and explain which ones to consider using in Chapter 8.

- Diversification: Buying individual stocks on your own is relatively costly unless you buy reasonable chunks (100 shares or so) of each stock. But in order to buy 100 shares each in, say, a dozen companies’ stocks to ensure diversification, you need about $60,000 if the stocks that you buy average $50 per share.

- Professional management: Even if you have big bucks to invest, mutual funds offer something that you can’t deliver: professional, full-time management. Mutual fund managers peruse a company’s financial statements and otherwise track and analyze its business strategy and market position. The best managers put in long hours and possess lots of expertise and experience in the field. (If you’ve been misled into believing that with minimal effort you can rack up market-beating returns by selecting your own stocks, please be sure to read the rest of this chapter.)

Look at it this way: Mutual funds are a huge time-saver. On your next day off, would you rather sit in front of your computer and do some research on semiconductor and toilet paper manufacturers, or would you rather enjoy dinner or a movie with family and friends? (The answer to that question depends on who your family and friends are!)

- Low costs — if you pick ’em right: To convince you that funds aren’t a good way for you to invest, those with a vested interest, such as stock-picking newsletter pundits, may point out the high fees that some funds charge. An element of truth rings here: Some funds are expensive, charging you a couple percent or more per year in operating expenses on top of hefty sales commissions.

But just as you wouldn’t want to invest in a fund that a novice with no track record manages, why would you want to invest in a high-cost fund? Contrary to the “You get what you pay for” notion often trumpeted by those trying to sell you something at an inflated price, some of the best managers are the cheapest to hire. Through a no-load (commission-free) mutual fund, you can hire a professional, full-time money manager to invest $10,000 for a mere $20 to $100 per year. Some index funds and exchange-traded funds charge even less.

- The issue of control is a problem for some investors. If you like being in control, sending your investment dollars to a seemingly black-box process where others decide when and in what to invest your money may unnerve you. However, you need to be more concerned about the potential blunders that you may make investing in individual stocks of your own choosing or, even worse, those stocks pitched to you by a broker.

- Taxes are a concern when you invest in mutual funds outside of retirement accounts. Because the fund manager decides when to sell specific stock holdings, some funds may produce relatively high levels of taxable distributions. Fear not — simply select tax-friendly funds if taxes concern you.

In Chapter 8, I discuss investing in the best mutual and exchange-traded funds that offer a high-quality, time- and cost-efficient way to invest in stocks worldwide.

Using hedge funds

Like mutual funds, hedge funds are a managed investment vehicle. In other words, an investment management team researches and manages the funds’ portfolio. However, hedge funds are oriented to affluent investors and typically charge steep fees — a 1.0 to 1.5 percent annual management fee plus a 20 percent cut of the annual fund returns.

No proof exists that hedge funds as a group perform better than mutual funds. In fact, the objective studies that I’ve reviewed show inferior hedge fund returns, which makes sense. Those high hedge fund fees depress their returns. Notwithstanding the small number of hedge funds that have produced better long-term returns, too many affluent folks invest in hedge funds due to the fund’s hyped marketing and the badge of exclusivity they offer.

Selecting individual stocks yourself

More than a few investing books suggest and enthusiastically encourage people to do their own stock picking. However, the vast majority of investors are better off not picking their own stocks, in my observations and experience.

I’ve long been an advocate of educating yourself and taking responsibility for your own financial affairs, but taking responsibility for your finances doesn’t mean that you should do everything yourself. Table 5-1 includes some thoughts to consider about choosing your own stocks.

Table 5-1 Why You’re Buying Your Own Stocks

|

Good Reasons to Pick Your Own Stocks |

Bad Reasons to Pick Your Own Stocks |

|

You enjoy the challenge. |

You think you can beat the best money managers. (If you can, you’re in the wrong profession!) |

|

You want to learn more about business. |

You want more control over your investments, which you think may happen if you understand the companies that you invest in. |

|

You possess a substantial amount of money to invest. |

You think that mutual funds are for people who aren’t smart enough to choose their own stocks. |

|

You’re a buy-and-hold investor. |

You’re attracted to the ability to trade your stocks anytime you want. |

Some popular investing books try to convince investors that they can do a better job than the professionals at picking their own stocks. Amateur investors, however, need to devote a lot of study to become proficient at stock selection. Many professional investors work 80 hours a week at investing, but you’re unlikely to be willing to spend that much time on it. Don’t let the popularity of those do-it-yourself stock-picking books lead you astray.

If you invest in stocks, I think you know by now that guarantees don’t exist. But as in many of life’s endeavors, you can buy individual stocks in good and not-so-good ways. So if you want to select your own individual stocks, check out Chapter 6, where I explain how to best research and trade them.

Spotting the Right Times to Buy and Sell

After you know about the different types of stock markets and ways to invest in stocks, you may wonder how you can build wealth with stocks and not lose your shirt. Nobody wants to buy stocks before a big drop.

As I discuss in Chapter 4, the stock market is reasonably efficient. A company’s stock price normally reflects many smart people’s assessments as to what is a fair price. Thus, it’s not realistic for an investor to expect to discover a system for how to “buy low and sell high.” Some professional investors may be able to spot good times to buy and sell particular stocks, but consistently doing so is enormously difficult.

Calculating price-earnings ratios

Suppose I tell you that the stock for Liz’s Distinctive Jewelry sells for $50 per share and that another stock in the same industry, The Jazzy Jeweler, sells for $100. Which would you rather buy?

If you answer, “I don’t have a clue because you didn’t give me enough information,” go to the head of the class! On its own, the price per share of stock is meaningless. Although The Jazzy Jeweler sells for twice as much per share, its profits may also be twice as much per share — in which case The Jazzy Jeweler stock price may not be out of line given its profitability.

![]()

Over the long term, stock prices and corporate profits tend to move in sync, like good dance partners. The price-earnings ratio, or P/E ratio (say, “P E” — the slash isn’t pronounced), compares the level of stock prices to the level of corporate profits, giving you a good sense of the stock’s value. Over shorter periods of time, investors’ emotions as well as fundamentals move stocks, but over longer terms, fundamentals possess a far greater influence on stock prices.

P/E ratios can be calculated for individual stocks as well as entire stock indexes, portfolios, or funds.

Over the past 100-plus years, the P/E ratio of U.S. stocks has averaged around 15. During times of low inflation, the ratio tends to be higher — in the high teens to low 20s. As I cautioned in the second edition of this book, published in 1999, the P/E ratio for U.S. stocks got into the 30s, well above historic norms even for a period of low inflation. Thus, the down market that began in 2000 wasn’t surprising, especially given the fall in corporate profits that put even more pressure on stock prices.

Just because U.S. stocks have historically averaged P/E ratios of about 15 doesn’t mean that every individual stock will trade at such a P/E. Here’s why: Suppose that you have a choice between investing in two companies, Superb Software and Tortoise Technologies. Say both companies’ stocks sell at a P/E of 15. If Superb Software’s business and profits grow 40 percent per year and Tortoise’s business and profits remain flat, which would you buy?

Because both stocks trade at a P/E of 15, Superb Software appears to be the better buy. Even if Superb’s stock continues to sell at 15 times its earnings, its stock price should increase 40 percent per year as its profits increase. Faster-growing companies usually command higher price-earnings ratios.

Citing times of speculative excess

Because the financial markets move on the financial realities of the economy as well as on people’s expectations and emotions (particularly fear and greed), you shouldn’t try to time the markets. Knowing when to buy and sell is much harder than you think.

In the sections that follow, I walk you through some of the biggest speculative bubbles. Although some of these examples are from prior decades and even centuries, I chose these examples because I find that they best teach the warning signs and dangers of speculative fever times.

The Internet and technology bubble

Note: This first section is excerpted from the second edition of this book, published in 1999, which turned out to be just one year before the tech bubble actually burst.

In the mid-1990s, a number of Internet-based companies launched initial public offerings of stock. (I discuss IPOs in Chapter 4.) Most of the early Internet company stock offerings failed to really catch fire. By the late 1990s, however, some of these stocks began meteoric rises.

The bigger-name Internet stocks included companies such as Internet service provider America Online, Internet auctioneer eBay, and Internet portal Yahoo! As with the leading new consumer product manufacturers of the 1920s that I discuss in the section “The 1920s consumer spending binge,” later in this chapter, many of the leading Internet company stocks skyrocketed. Please note that the absolute stock price per share of the leading Internet companies in the late 1990s was meaningless. The P/E ratio is what mattered. Valuing the Internet stocks based upon earnings posed a challenge because many of these Internet companies were losing money or just beginning to make money. Some Wall Street analysts, therefore, valued Internet stocks based upon revenue and not profits.

Now, some of these Internet companies may go on to become some of the great companies and stocks of future decades. However, consider this perspective from veteran money manager David Dreman: “The Internet stocks are getting hundredfold more attention from investors than, say, a Ford Motor in chat rooms online and elsewhere. People are fascinated with the Internet — many individual investors have accounts on margin. Back in the early 1900s, there were hundreds of auto manufacturers, and it was hard to know who the long-term survivors would be. The current leaders won’t probably be long-term winners.”

Internet stocks aren’t the only stocks being swept to excessive prices relative to their earnings at the dawn of the new millennium. Various traditional retailers announced the opening of Internet sites to sell their goods, and within days, their stock prices doubled or tripled. Also, leading name-brand technology companies, such as Dell Computer, Cisco Systems, Lucent, and PeopleSoft, traded at P/E ratios in excess of 100. Investment brokerage firm Charles Schwab, which expanded to offer Internet services, saw its stock price balloon to push its P/E ratio over 100. As during the 1960s and 1920s, name-brand growth companies soared to high P/E valuations. For example, coffee purveyor Starbucks at times had a P/E near 100.

Also, remember that if a company taps in to a product line or way of doing business that proves highly successful, that company’s success invites lots of competition. So you need to understand the barriers to entry that a leading company has erected and how difficult or easy it is for competitors to join the fray. Also, be wary of analysts’ predictions about earnings and stock prices. As more and more investment banking analysts initiated coverage of Internet companies and issued buy ratings on said stocks, investors bought more shares. Analysts, who are too optimistic (as shown in numerous independent studies), have a conflict of interest because the investment banks that they work for seek to cultivate the business (new stock and bond issues) of the companies that they purport to rate and analyze. The analysts who say, “buy, buy, buy all the current market leaders” are the same analysts who generate much new business for their investment banks and get the lucrative job offers and multimillion-dollar annual salaries.

Presstek, a company that uses computer technology for direct imaging systems, rose from less than $10 per share in mid-1994 to nearly $100 per share just two years later — another example of supposed can’t-lose technology that crashed and burned. As was the case with Iomega, herds of novice investors jumped on the Presstek bandwagon simply because they believed that the stock price would keep rising. By 1999, less than three years after hitting nearly $100 per share, the stock price plunged more than 90 percent to about $5 per share. It’s been recently trading under $1 per share.

ATC Communications, which was similar to Iomega and glowingly recommended by the Motley Fool website, plunged by more than 80 percent in a matter of months before the Fools recommended selling.

The Japanese stock market juggernaut

Lest you think that the United States cornered the market on manias, overseas examples abound. A rather extraordinary mania happened not so long ago in the Japanese stock market.

After Japan’s crushing defeat in World War II, its economy was in shambles. Two major cities — Hiroshima and Nagasaki — were destroyed, and more than 200,000 people died from atomic bombs.

Out of the rubble, Japan emerged a strengthened nation that became an economic powerhouse. Over the course of 22 years, from 1967 to 1989, Japanese stock prices rose thirtyfold (an amazing 3,000 percent) as the economy boomed. From 1983 to 1989 alone, Japanese stocks soared more than 500 percent.

In terms of the U.S. dollar, the Japanese stock market rise was all the more stunning, because the dollar lost value versus Japan’s currency, the yen. The dollar lost about 65 percent of its value during the big run-up in Japanese stocks. In dollar terms, the Japanese stock market rose an astonishing 8,300 percent from 1967 to 1989.

Borrowing heavily was easy to do; Japan’s banks were awash in cash, and it was cheap to borrow. Established investors could make property purchases with no money down. Cash abounded from real estate as the price of land in Tokyo soared 500 percent from 1985 to 1990. Despite the fact that Japan has only 1⁄25th as much land as the United States, Japan’s total land values at the close of the 1980s were four times that of all the land in the United States!

Speculators also used futures and options (discussed in Chapter 1) to gamble on higher short-term Japanese stock market prices. (Interestingly, Japan doesn’t allow selling short.)

Price-earnings ratios? Forget about it. To justify the high prices that they paid for stocks, Japanese market speculators pointed out that the real estate that many companies owned was zooming to the moon and making companies more valuable.

Price-earnings ratios on the Japanese market soared during the early 1980s and ballooned to more than 60 times earnings by 1987. As I point out elsewhere in this chapter, such lofty P/E ratios were sometimes awarded to select individual stocks in the United States. But the entire Japanese stock market, which included many mediocre and not-so-hot companies, possessed P/E ratios of 60-plus!

When Japan’s Nippon Telegraph and Telephone went public in February 1987, it met such frenzied enthusiasm that its stock price was soon bid up to a stratospheric 300-plus price-earnings ratio. At the close of 1989, Japan’s stock market, for the first time in history, unseated the U.S. stock market in total market value of all stocks. And this feat happened despite the fact that the total output of the Japanese economy was less than half that of the U.S. economy.

Even some U.S. observers began to lose sight of the big picture and added to the rationalizations for the high levels of Japanese stocks. After all, it was reasoned, Japanese companies and executives were a tightly knit and closed circle, investing heavily in the stocks of other companies that they did business with. The supply of stock for outside buyers was thus limited as companies sat on their shares.

Corporate stock ownership went further, though, as stock prices were sometimes manipulated. Speculators gobbled up the bulk of outstanding shares of small companies and traded shares back and forth with others whom they partnered with to drive up prices. Company pension plans began to place all (as in 100 percent) of their employees’ retirement money in stocks with the expectation that stock prices would always keep going up.

The collapse of the Japanese stock market was swift. After peaking at the end of 1989, the Tokyo market fell nearly 50 percent in the first nine months of 1990 alone. By the middle of 1992, Japanese stocks had dropped nearly 65 percent — a decline that the U.S. market hasn’t experienced since the Great Depression. Prices then stagnated during the rest of the 1990s and then fell again in the 2000s until 2008, putting it at a level that was more than 80 percent lower than the peak reached nearly two decades prior. Japanese investors who borrowed lost everything. The total loss in stock market value was about $3 trillion, about the size of the entire Japanese annual output.

Several factors finally led to the pricking of the Japanese stock market bubble. Japanese monetary authorities tightened credit as inflation started to creep upward and concern increased over real estate market speculation. As interest rates began to rise, investors soon realized that they could earn 15 times more interest from a safe bond versus the paltry yield on stocks.

As interest rates rose and credit tightened, speculators were squeezed first. Real estate and stock market speculators began to sell their investments to pay off mounting debts. Higher interest rates, less-available credit, and the already grossly inflated prices greatly limited the pool of potential stock buyers. The falling stock and real estate markets fed off each other. Investor losses in one market triggered more selling and price drops in the other. The real estate price drop was equally severe, registering 50 to 60 percent or more in most parts of Japan after the late 1980s.

The 1960s weren’t just about rock ’n’ roll

The U.S. stock market mirrored the climate of the country during this decade of change and upheaval. The stock market experienced both good years and bad years, but overall it gained.

During the 1960s, consumer product companies’ stocks were quite popular and were bid up to stratospheric valuations. When I say “stratospheric valuations,” I mean that some stock prices were high relative to the company’s earnings — my old friend, the price-earnings (P/E) ratio. Investors had seen such stock prices rise for many years and thought that the good times would never end.

Take the case of Avon Products, which sells cosmetics door-to-door, primarily with an army of women. During the late 1960s, Avon’s stock regularly sold at a P/E of 50 to 70 times earnings. (Remember, the market average is about 15.) After trading as high as $140 per share in the early 1970s, Avon’s stock took more than two decades to return to that high level. Remember that during this time period the overall U.S. stock market rose more than tenfold!

- The company’s profits might continue to grow, but investors may decide that the stock isn’t such a great long-term investment after all and not worth, say, a P/E of 60. Consider that if investors decide it’s worth only a P/E of 30 (still a hefty P/E), the stock price would drop 50 percent to cut the P/E in half.

- The second shoe that can drop is the company’s profits or earnings. If profits fall, say, 20 percent, as Avon’s did during the 1974–75 recession, the stock price will fall 20 percent, even if it continues to sell for 60 times its earnings. But when earnings drop, investors’ willingness to pay an inflated P/E plummets along with the earnings. So when Avon’s profits finally did drop, the P/E that investors were willing to pay plunged to 9. Thus, in less than two years, Avon’s stock price dropped nearly 87 percent!

Avon wasn’t alone in its stock price soaring to a rather high multiple of its earnings in the 1960s and early 1970s. Well-known companies such as Black & Decker (which has since merged into Stanley Works), Eastman Kodak (which later declared bankruptcy), and Kmart (which used to be called S.S. Kresge in those days and was later merged into Sears Holdings) sold for 60 to as much as 100 times earnings. Many other well-known and smaller companies sold at similar and even more outrageous premiums to earnings.

The 1920s consumer spending binge

The Dow Jones Industrial Average soared nearly 500 percent in a mere eight years, from 1921 to 1929, allowing for one of the best bull market runs for the U.S. stock market. The country and investors had good reason for economic optimism. New devices — telephones, cars, radios, and all sorts of electric appliances — were making their way into the mass market. The stock price of RCA, the radio manufacturer, for example, ballooned 5,700 percent during this eight-year stretch.

Speculation in the stock market moved from Wall Street to Main Street. Investors during the 1920s were able to borrow lots of money to buy stock through margin borrowing. You can still margin borrow today — for every dollar that you put up, you may borrow an additional dollar to buy stock. At times during the 1920s, investors could borrow up to nine dollars for every dollar that they had in hand. The amount of margin loans outstanding swelled from $1 billion in the early 1920s to more than $8 billion in 1929. When the market plunged, margin calls (which require putting up more money due to declining stock values) forced margin borrowers to sell their stock, thus exacerbating the decline.

The steep run-up in stock prices was also due in part to market manipulation. Investment pools used to buy and sell stocks among one another, thus generating high trading volume in a stock, which made it appear that interest in the stock was great. Also, writers who dispensed enthusiastic prognostications about said stock were in cahoots with pool operators. (Reforms later passed by the Securities and Exchange Commission addressed these problems.)

Not only were members of the public largely enthusiastic, but so, too, were the supposed experts. After a small decline in September 1929, economist Irving Fisher said in mid-October, “Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” High? Yes! Permanent plateau? Investors wish!

On October 25, 1929, just days before all heck began breaking loose, President Herbert Hoover said, “The fundamental business of the country … is on a sound and prosperous basis.” Days later, multimillionaire oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller said, “Believing that fundamental conditions of the country are sound … my son and I have for some days been purchasing sound common stocks.”

By December of that same year, the stock market had dropped by more than 35 percent. General Electric President Owen D. Young said at that time, “Those who voluntarily sell stocks at current prices are extremely foolish.” Well, actually not. By the time the crash had run its course, the market had plunged 89 percent in value in less than three years.

The economy went into a tailspin. Unemployment soared to more than 25 percent of the labor force. Companies entered this period with excess inventories, which mushroomed further when people slashed their spending. High overseas tariffs stifled American exports. Thousands of banks failed, because early bank failures triggered “runs” on other banks. (No FDIC insurance existed in those days.)

I’m not saying that you need to sell your current stock holdings if you see an investment market getting frothy and speculative. As long as you diversify your stocks worldwide and hold other investments, such as real estate and bonds, the stocks that you hold in one market need to be only a fraction of your total holdings. Timing the markets is difficult: You can never know how high is high and when it’s time to sell and then know how low is low and when it’s time to buy. And if you sell non-retirement account investments at a profit, you end up sacrificing a lot of the profit to federal and state taxes.

Buying more when stocks are “on sale”

Along with speculative buying frenzies come valleys of pessimism when stock prices are falling sharply. Having the courage to buy when stock prices are “on sale” can pay big returns.

In the early 1970s, interest rates and inflation escalated. Oil prices shot up as an oil embargo choked off supplies, and Americans had to wait in long lines for gas. Gold prices soared, and the U.S. dollar plunged in value on foreign currency markets.

If the economic problems weren’t enough to make most everyone gloomy, the U.S. political system hit an all-time low during this period as well. Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned in disgrace under a cloud of tax-evasion charges. Then Watergate led to President Richard Nixon’s August 1974 resignation, the first presidential resignation in the nation’s history.

When all was sold and done, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted more than 45 percent from early 1973 until late 1974. Among the stocks that fell the hardest were those that were most popular and selling at extreme multiples of earnings in the late 1960s and early 1970s. (See the section “The 1960s weren’t just about rock ’n’ roll,” earlier in this chapter.)

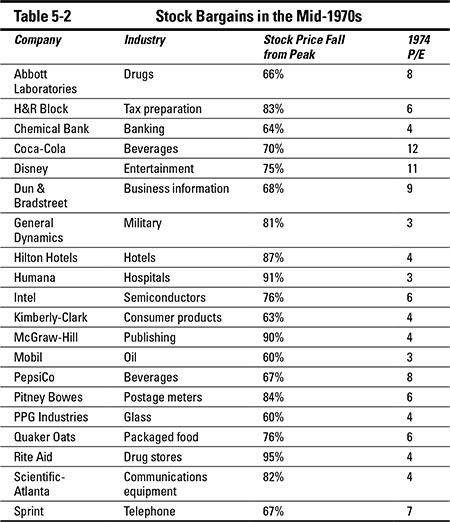

Take a gander at Table 5-2 to see the drops in some well-known companies and see how cheaply these stocks were valued relative to corporate profits (look at the P/E ratios) after the worst market drop since the Great Depression.

Those who were too terrified to buy stocks in the mid-1970s actually had time to get on board and take advantage of the buying opportunities. The stock market did have a powerful rally and, from its 1974 low, rose nearly 80 percent over the next two years. But over the next half dozen years, the market backpedaled, losing much of its gains.

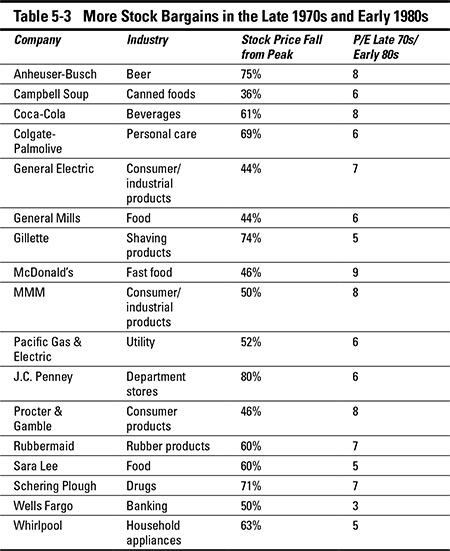

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, inflation continued to escalate well into double digits. Corporate profits declined further, and unemployment rose higher than in the 1974 recession. Although some stocks dropped, others simply treaded water and went sideways for years after major declines in the mid-1970s. As some companies’ profits increased, P/E bargains abounded (as shown in Table 5-3).

During the 2008 financial crisis, panic (and talk of another Great Depression) was in the air and stock prices dropped sharply. Peak to trough, global stock prices plunged 50-plus percent. While some companies went under (and garnered lots of news headlines), those firms were few in number and were the exception rather than the norm. Many terrific companies weathered the storm, and their stock could be scooped up by investors with cash and courage at attractive prices and valuations.

Avoiding Problematic Stock-Buying Practices

Beware of broker conflicts of interest

Some investors make the mistake of investing in individual stocks through a broker who earns a living from commissions. The standard pitch from these firms and their brokers is that they maintain research departments that monitor and report on stocks. Their brokers, using this research, tell you when to buy, sell, or hold. Sounds good in theory, but this system has significant problems.

Brokerage analysts who, with the best of intentions, write negative reports about a company find their careers hindered in a variety of ways. Some firms fire such analysts. Companies that the analysts criticize exclude those analysts from analyst meetings about the company. So most analysts who know what’s good for their careers and their brokerage firms don’t write disapproving reports (but some do take chances).

Although investment insiders know that analysts are pressured to be overly optimistic, historically it’s been hard to find a smoking gun to prove that this pressuring is indeed occurring, and few people are willing to talk on the record about it. One firm was caught encouraging its analysts via a memo not to say negative things about companies. As uncovered by Wall Street Journal reporter Michael Siconolfi, Morgan Stanley’s head of new stock issues stated in a memo that the firm’s policy should include “no negative comments about [its] clients.” The memo also stated that any analyst’s changes in a stock’s rating or investment opinion “which might be viewed negatively” by the firm’s clients had to be cleared through the company’s corporate finance department head.

Various studies of the brokerage firm’s stock ratings have conclusively demonstrated that from a predictive perspective, most of its research is barely worth the cost of the paper that it’s printed on. In Chapter 6, I recommend independent research reports worth perusing. In Chapter 9, I cover the important issues that you need to consider when you select a good broker.

Don’t short-term trade or try to time the market

Unfortunately (for themselves), some investors track their stock investments closely and believe that they need to sell after short holding periods — months, weeks, or even days. With the growth of Internet and computerized trading, such shortsightedness has taken a turn for the worse as more investors now engage in a foolish process known as day trading, where they buy and sell a stock within the same day!

- Higher trading costs: Although the commission that you pay to trade stocks has declined greatly in recent years, especially through online trading (which I discuss in Chapter 9), the more you trade, the more of your investment dollars go into a broker’s wallet. Commissions are like taxes — once paid, those dollars are forever gone, and your return is reduced. Similarly, the spread between the price you pay to purchase a stock and the price you would receive to sell the same stock (known as the bid-ask spread) can be a significant drag on your investment return.

- More taxes (and tax headaches): When you invest outside of tax-sheltered retirement accounts, you must report on your annual income tax return every time that you buy and then sell a stock. After you make a profit, you must part with a good portion of it through the federal and state capital gains tax that you owe from the sale of your stock. If you sell a stock within one year of buying it, the IRS and most state tax authorities consider your profit short-term, and you owe a much higher rate of tax than if you hold your stock for more than a year. Holding your stock for more than a year qualifies you for the favorable long-term capital gains tax rate (a topic that I discuss in Chapter 21). The return that you keep (after taxes) is more important than the return that you make (before taxes).

- Lower returns: If stocks increase in value over time, long-term buy-and-hold investors enjoy the fruits of the stock’s appreciation. However, if you jump in and out of stocks, your money spends a good deal of time not invested in stocks. The overall level of stock prices in general and individual stocks in particular sometimes rises sharply during short periods of time. Thus, short-term traders inevitably miss some stock run-ups. The best professional investors I know don’t engage in short-term trading for this reason (as well as because of the increased transaction costs and taxes that such trading inevitably generates).

- Lost opportunities: Most of the short-term traders I’ve met over the years spend inordinate amounts of time researching and monitoring their investments. During the late 1990s, I began to hear of more and more people who quit their jobs so they could manage their investment portfolios full time! Some of the firms that sell day-trading seminars tell you that you can make a living trading stocks. Your time is clearly worth something. Put your valuable time into working a little more on building your own business or career instead of wasting all those extra hours each day and week watching your investments like a hawk, which hampers rather than enhances your returns.

- Poorer relationships: Time is your most precious commodity. In addition to the financial opportunities that you lose when you indulge in unproductive trading, you need to consider the personal consequences as well. Like drinking, smoking, and gambling, short-term trading is an addictive behavior. Spouses of day traders and other short-term traders report unhappiness over how much more time and attention their mates spend on their investments than on their families. And what about the lack of attention that day traders and short-term traders give other relatives and friends? (See the sidebar “Recognizing an investment gambling problem” in this chapter to help determine whether you or a loved one has a gambling addiction.)

How a given stock performs in the next few hours, days, weeks, or even months may have little to do with the underlying financial health and vitality of the company’s business. In addition to short-term swings in investor emotions, unpredictable events (such as the emergence of a new technology or competitor, analyst predictions, changes in government regulation, and so on) push stocks one way or another in the short term.

All these reasons should convince you to avoid engaging in day trading or market timing (trying to jump in and out of particular investments based on current news and other factors). Be skeptical of any market prognosticator who claims to be able to time the markets and boasts of numerous past correct calls and market-beating returns.

Be wary of gurus

It’s tempting to wish that you could consult a guru who could foresee an impending major decline and get you out of an investment before it tanks. Believe me when I say that plenty of these pundits are talking up such supposed prowess. The financial crisis of 2008 brought an avalanche of prognosticators out of the woodwork claiming that if you had been listening to them, you could have not only sidestepped losses but also made money.

As you develop your plans for an investment portfolio, be sure to take a level of risk and aggressiveness with which you’re comfortable. Remember that no pundit has a working crystal ball that can tell you what’s going to happen with the economy and financial markets in the future.

Shun penny stocks

Even worse than buying stocks through a broker whose compensation depends on what you buy and how often you trade is purchasing penny stocks through brokers who specialize in such stocks. Tens of thousands of smaller-company stocks trade on the over-the-counter market. Some of these companies are quite small and sport low prices per share that range from pennies to several dollars, hence the name penny stocks.

Here’s how penny-stock brokers typically work: Many of these firms purchase prospect lists of people who have demonstrated a propensity for buying other lousy investments by phone. Brokers are taught to first introduce themselves by phone and then call back shortly thereafter with a tremendous sense of urgency about a great opportunity to get in on the “ground floor” of a small but soon-to-be stellar company. Not all these companies and stocks have terrible prospects, but many do.

A number of penny-stock brokerage firms are known for engaging in manipulation of stock prices. They drive up prices of selected shares to suck in gullible investors and then leave the public holding the bag. These firms may also encourage companies to issue new overpriced stock that their brokers can then sell to folks.

The Keys to Stock Market Success

- Don’t try to time the markets. Anticipating where the stock market and specific stocks are heading is next to impossible, especially over the short term. Economic factors, which are influenced by thousands of elements as well as human emotions, determine stock market prices. Be a regular buyer of stocks with new savings. As I discuss earlier in this chapter, consider buying more stocks when they’re on sale and market pessimism is running high. Don’t make the mistake of bailing out when the market is down!

- Diversify your investments. Invest in the stocks of different-sized companies in varying industries around the world. When assessing your investments’ performance, examine your whole portfolio at least once a year and calculate your total return after expenses and trading fees.

- Keep trading costs, management fees, and commissions to a minimum. These costs represent a big drain on your returns. If you invest through an individual broker or a financial advisor who earns a living on commissions, odds are that you’re paying more than you need to be. And you’re likely receiving biased advice, too.

- Pay attention to taxes. Like commissions and fees, federal and state taxes are a major investment “expense” that you can minimize. Contribute most of your money to your tax-advantaged retirement accounts. You can invest your money outside of retirement accounts, but keep an eye on taxes (see Chapter 3). Calculate your annual returns on an after-tax basis.

- Don’t overestimate your ability to pick the big-winning stocks. One of the best ways to invest in stocks is through mutual funds (see Chapter 8), which allow you to use an experienced, full-time money manager at a low cost to perform all the investing grunt work for you.

When you purchase a share of a company’s stock, you can profit from your ownership in two ways:

When you purchase a share of a company’s stock, you can profit from your ownership in two ways: Conspicuously absent from this list of major stock market indexes is the NASDAQ index. With the boom in technology stock prices in the late 1990s, CNBC and other financial media started broadcasting movements in the technology-laden NASDAQ index, thereby increasing investor interest and the frenzy surrounding technology stocks. (See the section titled “

Conspicuously absent from this list of major stock market indexes is the NASDAQ index. With the boom in technology stock prices in the late 1990s, CNBC and other financial media started broadcasting movements in the technology-laden NASDAQ index, thereby increasing investor interest and the frenzy surrounding technology stocks. (See the section titled “ The simplest and best way to make money in the stock market is to consistently and regularly feed new money into building a diversified and larger portfolio. If the market drops, you can use your new investment dollars to buy more shares. The danger of trying to time the market is that you may be “out” of the market when it appreciates greatly and “in” the market when it plummets.

The simplest and best way to make money in the stock market is to consistently and regularly feed new money into building a diversified and larger portfolio. If the market drops, you can use your new investment dollars to buy more shares. The danger of trying to time the market is that you may be “out” of the market when it appreciates greatly and “in” the market when it plummets. What I find troubling about investors piling in to the leading, name-brand stocks, especially in Internet and technology-related fields, is that many of these investors don’t even know what a price-earnings ratio is and why it’s important. Before you invest in any individual stock, no matter how great a company you think it is, you need to understand the company’s line of business, strategies, competitors, financial statements, and price-earnings ratio versus the competition, among many other issues. Selecting and monitoring good companies take lots of research, time, and discipline.

What I find troubling about investors piling in to the leading, name-brand stocks, especially in Internet and technology-related fields, is that many of these investors don’t even know what a price-earnings ratio is and why it’s important. Before you invest in any individual stock, no matter how great a company you think it is, you need to understand the company’s line of business, strategies, competitors, financial statements, and price-earnings ratio versus the competition, among many other issues. Selecting and monitoring good companies take lots of research, time, and discipline. Many brokerage firms happen to be in another business that creates enormous conflicts of interest in producing objective company reviews. These investment firms also solicit companies to help them sell new stock and bond issues. To gain this business, the brokerage firms need to demonstrate enthusiasm and optimism for the company’s future prospects.

Many brokerage firms happen to be in another business that creates enormous conflicts of interest in producing objective company reviews. These investment firms also solicit companies to help them sell new stock and bond issues. To gain this business, the brokerage firms need to demonstrate enthusiasm and optimism for the company’s future prospects.