Chapter 2

Banking and the Risk Environment

1. THE GLOBAL RISK ENVIRONMENT

We live in interesting times. The global economy has changed significantly in the last decade. Emerging market economies have increased their share, for much of that time, of a rapidly expanding global economy, from around 25 percent to around 50 percent of global GDP (measured at purchasing power parity).

Growth has not, however, been evenly distributed. Developed economies that have been globally dominant in both economic and political terms for much of the period since World War II have increasingly suffered, since the turn of the millennium, from low rates of economic growth. This has been especially true since they entered a recessionary period, which we may date from the collapse of the U.S. investment bank Lehman Brothers in 2007.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers itself was consequential upon the collapse of the U.S. mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market. This collapse brought about a general reduction in the supply of liquidity across the interconnected banking systems of many developed economies, as banks restricted their lending to each other, fearful of which banks might be exposed to the very large credit losses from their holdings of MBS and other similar collateralised debt obligations (CDO).

As a number of very large international banks suffered from both high credit losses and illiquid markets, they were unable to fund their balance sheets and had to be funded and recapitalised by the governments of the countries of their incorporation. The largest of all was Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), which shortly before the crisis was the world’s largest bank as measured by assets. RBS had to be recapitalised by the UK government, which acquired some 80 percent of the bank’s share capital. In some countries, most notably the Irish Republic, the recapitalisation of the countries’ banks placed great strain upon their national treasuries.

The increase in government debt associated with bank recapitalisation was combined with the much greater government debt resulting from the deficit spending by countries acting to counteract the recessionary effects of the contraction of bank credit (and therefore of the money supply) by their troubled and in many cases bankrupt banking systems. This resulted in the doubling of government debt to GDP ratios in many developed economies, in many cases rising to levels not seen since World War II.

In the euro area, the recession also highlighted weaknesses in the structure of its monetary system. The effective fixing of exchange rates between the very different national economies had initially led to each member country being able to borrow as though there were little if any differential credit risk between the individual member countries. Thus, at its most extreme, Greece was able to borrow at a very small premium to Germany. The recession across the euro area, however, soon resulted in member countries’ relative economic competitiveness (and hence creditworthiness) becoming obvious. It became clear that whilst Germany was very competitive and able to increase exports, most especially to emerging market economies such as China and India, many other member states were not so internationally competitive. Thus, in spite of significant reductions both in government spending and in wages and employment conditions in the economy as a whole, it was unlikely all euro area countries could service all of the debts their respective governments had incurred.

The fundamental economic position of these euro area countries was made worse by the treaty limitations on the European Central Bank (ECB), which despite its title does not have the intervention powers of a traditional national central bank to underwrite national debt by the direct purchase of government bonds. This limitation, appeared to have been greatly aggravated by the reluctance until very recently (as of April 2012) of the German government to allow the ECB to use the powers it does have to intervene in government bond markets on anything like the scale of the Federal Reserve Bank in the United States or the Bank of England in the United Kingdom.

The final outcome of what is, at the time of writing, a continuing crisis cannot be predicted. A number of lessons have, however, been learned, especially in respect of the risks inherent in a fractional reserve banking system. The most important of these are:

- The need for banks to hold sufficient high quality capital against the credit, market, and operational risks of the banking system.

- The over-reliance of commercial banks on their ability to turn banking assets into cash through markets (market liquidity).

- Commercial banks’ need to ensure that they reduce the extent of their mismatches between the term structure of maturities of banks’ assets and liabilities (funding liquidity).

These risks are not new to banking. However, new regulation—most especially in the shape of the new international standard, Basel III—and the concerns of governments and bank shareholders to ensure that banks are economically more robust against multiple financial risks into the future are ensuring that banks focus on these risks and strengthen their capital and liquidity structures.

2. THE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

The regulator’s reaction to the risk environment in banking has been developed on a global basis through the development of the Basel III Accord on which it is expected global banking regulation will be based, though there are some exceptions to this, most notably in the United States with the Dodd-Frank Act and lately in the United Kingdom where banks will be subject to the implementation of the recommendations of the Independent Commission on Banking (ICB) as well as to the European Union (EU) implementation of Basel III through the fourth Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV). The CRD IV has the force of law throughout the EU and this is likely to maintain its leading role in both developing and implementing the Basel Accords.

The risk basis of regulation has been further developed under Basel III, and whilst there have been some significant alterations and additions to the previous Basel II regulatory environment, the Three Pillars of Regulation established under Basel II remain and indeed are enhanced under Basel III.

2.1 Pillar 1—Minimum Capital Requirements

Requires computation of minimum capital requirements for credit risk and operational risk (in addition to market risk under 1996 amendment).

Individual capital weights, however, differ significantly between Basel II and Basel III, with much higher weights for traded assets, assets subject to securitisations, derivative transactions, and more contentiously for the short term (under one year) funding of trade in goods and services.

Pillar 1 Credit Risk

Pillar 1 allows for three possible approaches to the computation of a bank’s credit risk. These approaches are the:

The standardised approach is computed primarily from the use of public ratings and is basically an enhanced version of the Basel I regime. The internal ratings–based (foundation) approach is based upon the use of a standardised model incorporating three main factors:

The third methodology is the internal ratings–based (advanced) approach, which draws on a bank-specific grading model. These models specifically do not, in their grading computations, take into account the portfolio effects that may come from the correlation between individual credits within a portfolio or from the relationships between portfolios of credit risk assets.

This does open up the issue of how such an approach can pass the “usage test” for such models, as many banks using advanced models will design the model to inform the bank of the addition to (or reduction from) total risk as a result of the purchase (or sale) of the asset. Such a risk measure requires the model to compute the assets risk, taking into account the portfolio of risk the bank has. The model will clearly and correctly show a different level of risk from the same asset across different banks with different portfolios (see Section 3 later).

Stress tests play an important role in determining capital requirements across all asset classes under Basel III, as regulators are looking to ensure bank capital levels are sufficient under such circumstances. Stress test models usually incorporate correlations both within and across asset classes. These correlations will change during stress circumstances, often rising steeply. This effect is known as dynamic conditional correlation.

Credit Risk Grading Models

There are three main approaches to the development of the credit models to support either of the internal ratings–based approaches for the grading of corporate credits, modified versions of which can be used to determine the relative standing of sovereign credits.

For all credit models Basel II requires that any model used must create a minimum of eight credit grades and must be capable of being mapped to publicly available credit grades. The reliance on such public credit grades has become more controversial in Basel III, as the main rating agencies had a poor record of grading credit across a wide spread of asset-backed securities (ABS) from the early stages of the financial crisis of 2007 on.

In the personal sector, the equivalent of these models is the use of credit scoring models, which look at a series of factors affecting a person’s ability to service debt to create the equivalent grading system. Such models often have highly granular structures with so called cut-off points, which determine the mapping of these models to historic defaults.

The gradings produced by all of these models can be affected by the provision by borrowers of collateral, and Basel III has a greater degree of recognition of a range of collateral and its ability to mitigate credit risks than was allowed under Basel II.

Owing to the particular problems associated with the misleading credit gradings provided by major public rating agencies to a broad swathe of securitised asset structures leading up to the financial crisis, there are under Basel III effectively a series of surcharges added to the capital requirements of grading model outturns as applied to securitised products.

Pillar 1 Operational Risk

Operational risk is defined as “the risk of loss from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events.”

As with credit risk, there are three approaches to the computation of bank capital required to back operational risk:

All approaches must be capable of mapping losses to the eight business lines (above) and risk event types (internal fraud; external fraud; employment practices and workplace safety; clients, products, and business practices; damage due to physical assets; business disruption and system failure; and execution, delivery, and process management).

Management and control processes are capable of being scored by using key risk indicators (KRI) and through techniques such as Six Sigma, which score processes by looking at measurement against “best practice,” such as the number of rejected applications for credit due to inadequate data collection.

Operational risk measurement produces a number of challenges that do not apply to credit or market risk.

- In data collection, there is the need to collect data on what are often termed “near misses.” The relevance of this can be seen, for example, in the collection of data on the number of times a mistake between the back and front offices in a dealing room results in a sale of USD against EUR being recorded as a purchase. If only the losses resulting from such a mistakes were recorded then there could be a significant under-recording of the number of mistakes being made.

- It can often be very difficult to determine the root cause of a particular operational risk incident. Is improper recording of a transaction a failure of training or of process? Are the IT systems at fault or are administrative policies not being embedded in operational procedures? Establishing a process for “root cause analysis” is vital to ensuring operational risks are properly recorded and the appropriate corrective action taken.

- There are reasons to suppose that the severity of operational risk events is systematically increasing, as greater reliance on automated IT systems means that when the system fails it will fail continuously. Other risks come from outsourcing, terrorism, and globalisation.

Pillar 1 Market Risk

The two approaches to market risk under Basel II are continued under Basel III. The simplest approach is the standardised approach, which consists of a set of capital additions required to address the exposures banks run to market risk. The process consists, in essence, of a number of “look-up tables” where capital is computed from the market positions run by the bank on both a net and gross basis. The latter has risen in importance, as the economic crisis of 2007 illustrated the importance of understanding counterparty credit risk and what can happen to the market exposures of a bank should a counterparty to a hedging transaction fail.

The issue of counterparty risk has indeed been a major driving force behind a number of reforms to derivatives trading, in particular where the market was dominated by transactions directly undertaken between banks. This over the counter (OTC) market created difficulties both for banks and regulators when they needed to understand the exposure any single counterparty institution had to other parties in the market. The main counterparty in a number of derivative transactions was found to be American Insurance Group (AIG), apparently much to the surprise of the U.S. regulators. Proposals under Basel III will result in the establishment of central clearing through so-called central counterparty clearing (CCPs) for most derivatives transactions in the future, making the exposures of institutions more transparent.

The second approach, one used by many banks, is the internal models approach. Under this approach, the regulators agree to the bank’s own models, much as they do for the internal ratings–based (advanced) approach for credit risk and the advanced measurement approach for operational risk.

Key elements of market risk models are:

- Calculation of the statistical parameters that describe the predicted movement in market prices.

- Statistical assumptions about the way in which prices will move in the future.

- Accuracy of the valuation process applied to the portfolio for each future scenario.

For the regulators to approve the model, it must fit with their model approval criteria, which has the following tests for the bank’s risk management system:

- The system is conceptually sound and implemented with integrity.

- The bank has sufficient staff trained in the use of sophisticated market risk management models (there must be skilled staff in the following key areas: trading, risk control, audit, and operations).

- Its models have a proven track record of measuring risk with reasonable accuracy.

- It carries out regular stress testing.

2.2 Pillar 2—Supervisory Review

Supervisory review is designed to:

- Uncover any capital requirements above the minimum level computed under Pillar 1 (e.g., due to excessive concentrations of risk).

- Uncover early actions that may be required to address emerging risks (e.g., growing backlogs of outstanding reconciliations).

- Closely follows current U.K. and U.S. practice.

It also introduces the computation of each individual bank’s capital and liquidity through the Individual Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) and the Individual Liquidity Adequacy Statement (ILAS).

Pillar 2 The Supervisory Review Process

Pillar 2 addresses three main areas of risk either not covered or outside of the scope of Pillar 1:

Pillar 2 identifies four core principles of supervisory review:

- Principle 1—Banks should have a process for assessing their overall capital adequacy in relation to their risk profile and a strategy for their capital levels.

- Principle 2—Supervisors should review and evaluate banks’ internal capital adequacy assessments and strategies, as well as their ability to monitor and ensure their compliance with regulatory capital ratios. Supervisors should take appropriate supervisory action if they are not satisfied with the result of this process.

- Principle 3—Supervisors should expect banks to operate above the minimum regulatory capital ratios and should have the ability to require banks to hold capital in excess of the minimum.

- Principle 4—Supervisors should seek to intervene at an early stage to prevent capital from falling below the minimum levels required to support the risk characteristics of a particular bank and should require rapid remedial action if capital is not maintained or restored.

These principles clearly indicate why supervisors are looking for banks to establish economic capital models (see Section 3 below).

2.3 Pillar 3—Market Discipline

Pillar 3 is the so-called market discipline pillar.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) defines market discipline as “the internal and external governance mechanism in a free market economy in the absence of direct government intervention.”

Market discipline is designed to help a bank’s shareholders and market analysts and to lead to greater transparency on issues such as a bank’s:

- Asset portfolio.

- Risk profile.

Pillar 3 Disclosure

The aim of Pillar 3 is to use the market discipline imposed by Basel III disclosure requirements to complement the operation of Pillars 1 and 2.

The Pillar 3 disclosure information is focused on capital adequacy information, not financial performance, and falls into the following main areas:

- The structure of capital.

- The risk exposures.

- The level of capital adequacy.

There is an extensive list of quantitative and qualitative disclosures under each area.

Whilst Basel does not require the disclosures to be reconciled with the bank’s financial accounts in a number of jurisdictions this will in practice be necessary due to the requirements of bodies responsible for financial reporting, such as government bodies and listing authorities.

The main areas for enhanced disclosure are:

- The structure of capital.

- The adequacy of capital.

- The risks to which banks are exposed, as well as the policies and techniques banks use to identify, measure, monitor, and control these risks. The disclosure must cover credit, market, and operational risks as well as interest rate and equity risks held in the banking book.

- Credit risk–specific disclosures, including total credit exposure and its distribution by product and by geography, industry, and maturity, as well as impaired loans and provisions relating thereto. Banks must also disclose their use of credit mitigation techniques such as netting or collateralisation and how such techniques are applied.

- Securitisation, banks undertaking securitisations, and/or investing in securitisations have additional disclosure requirements.

- Market risk by interest rate risk, equity position risk, foreign exchange risk, and commodity risk

- Operational risk, where the technique used must be disclosed.

Disclosures also differ significantly depending on whether a bank is using the standardised or either of the internal ratings-based approaches to calculating credit risk or is using models for market risk, in which cases significant disclosures of the model approach, its calibration, and its testing should also be disclosed.

2.4 Liquidity Risk

Both Basel I and Basel II had little to say on liquidity risk. This may in part have been due to an increasing academic fashion for assuming markets were characterised by plentiful and always available sources of funding, a corollary of the “efficient market hypothesis.” Indeed, in the decade before the 2007 Lehman crisis, markets had been a ready source of liquidity for bank assets through the rapidly growing asset repurchase (repo) and securitisation markets. The demise of Lehman resulted in a rapid and general decline in the availability of funding to virtually all bank asset markets, as the value of bank assets and the solvency of a number of banks were increasingly called into question.

The new Basel III regulatory proposals attempt to address this deficiency and to improve the liquidity position of banks by:

- Curbing their ability to create a large maturity mismatches, including the imposition of a “stable funding ratio.”

- Ensuring that over a 30-day period they have a positive daily cash flow (i.e., their daily “cash inflow” from inter alia maturing assets and contracted funding is greater than their daily “cash outflow” from inter alia contractual lending obligations and maturing deposits).

- Ensuring banks hold a quantity of high quality liquid assets (HQLA) that can be turned into cash through markets and in need through the opening of a discount “window” at the central bank. This is called a “stock” liquidity requirement.

Under Basel III there is in general a greater emphasis on banks’ funding liquidity and specifically upon the retail deposit base as a stable source of funds.

The use of government bonds as the major source of HQLA to meet their “stock” liquidity requirement is, however, being increasingly called into question, as the very high national debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratios of a number of major economies, combined with poor GDP growth prospects, have resulted in their government bonds being downgraded from AAA status. The United States was a recent and extremely important example of this when, in August 2011, Standard & Poor’s, the United States–based major rating agency downgraded U.S. government debt from AAA to AA+; U.S. debt has also been downgraded by both a German and a Chinese rating agency.

In the euro area in January 2012, S&P stripped its AAA rating from France and downgraded eight other Eurozone countries. Moreover, the effective default of Greece in 2012 on its national debt has dealt a major blow to the whole idea that euro area countries can rely on their central bank (the ECB) to undertake market actions to ensure national debt is repaid, at least in nominal terms.

As a result of these problems it is increasingly clear that government bonds cannot simply be accepted as credit risk free, and certainly not in the case of euro area governments, which lack the ability to control the issue of their own currency. Losses for many banks on their holding of euro area government bonds are already substantial, as such bonds are accounted for as either “held for trading purposes” or “available for sale” under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and are therefore either marked to market through the profit and loss or capital accounts, and the bonds are generally medium or long term. This accounting treatment leads to very large adjustments to profit and loss and/or the bank’s capital as the credit spreads on these bonds widen. Because of the extent of exposure of many European banks to their national governments, this is now requiring some major European banks to undertake extensive recapitalisation.

This should lead to some rethinking of the Basel III liquidity rules, as they clearly fail to fully recognise the risks inherent in banks holding large quantities of government bonds as encouraged by the new Basel III “stock” liquidity regime. A rethink may indeed prove a good basis for a more inclusive set of global banking liquidity rules that would level the playing field between Shari’ah-compliant and conventional banks (see Sections 5.2 and 5.3).

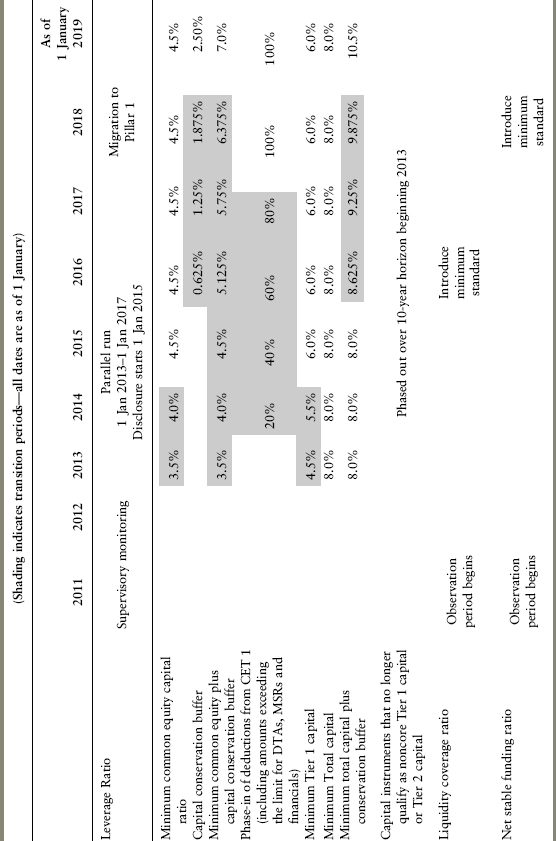

2.5 Leverage Ratio

Basel III also introduces a simple Leverage Ratio at 3% (Total Tier 1 Capital / Total On and Off Balance Sheet Exposures). The 3% ratio requirement will parallel run from 1 January 2013 to 2017, meaning that the Committee will track the ratio, its component factors, and impact over this period and will require Bank level disclosure of the ratio and its factors from 1 January 2015. Based on the results of the parallel run, final adjustments to the ratio will be carried out in the first half of 2017, and it will be fully effective from 1st January 2018.

2.6 The Basel III Liquidity Regime: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR)

The LCR has two components:

![]()

HQLA are comprised of Level 1 and Level 2 assets, with Level 2 assets comprising Level 2a and Level 2b.

The high quality liquid assets included in the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) are:

After the application of the haircuts, Level 2b assets cannot exceed 15% of a bank’s total high quality liquid assets, and they count towards the limit that the total amount of Level 2 assets (Level 2a plus Level 2b assets) may not exceed 40% of a bank’s total high quality liquid assets.

2.7 The Basel III Liquidity Regime: The Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR)

The NSFR test considers the robustness of a bank’s funding position (based on the bank’s assets/activities) over a one-year period. It is assumed that the bank is then subject to an institution-specific stress of which there is public awareness and which results in:

- a significant decline in profitability or solvency as a result of increased credit, market, operation or other risk;

- a potential downgrade in debt; counterparty credit or deposit rating by any nationally recognised organisation; and/or

- a material event which calls into the question the reputation/credit quality of the Bank.

The NSFR is meant to eliminate funding mismatches between a bank’s assets and liabilities by establishing a minimum acceptable amount of stable funding based on the liquidity characteristics of a firm’s assets and activities over a one-year horizon. Implementation of the NSFR is scheduled for January 2018, with final revisions to be made by 2016. Until that point, the Basel Committee will observe the impact of the ratio and make changes if necessary.

The NSFR is defined as the available amount of stable funding divided by the required amount of stable funding. A minimum of 100% is obligatory under the rules.

![]()

The amount of required stable funding (RSF) is measured using supervisory assumptions on the broad characteristics of the liquidity risk profiles of a firm’s assets and off–balance-sheet exposures. A certain RSF factor is assigned to each asset type, with those assets deemed to be more liquid receiving a lower RSF factor and therefore requiring less stable funding.

Thus, for example, it is proposed that:

The aggregate RSF for a bank is simply calculated as the aggregate of each asset and off balance sheet item multiplied by the RSF Factor relevant to it.

Stable Funding is described as those types and amounts of equity and debt financing which are expected to be reliable sources of funds over a one year period of stress, that is:

The ASF is calculated as follows: The carrying value of all equity and liabilities referred to in (i) to (v) above are assigned to one of 5 categories, each of which categories has a percentage multiplier (“ASF Factor”) allocated to it (the ASF Factor is intended to reflect the availability and quality of the Stable Funding type for these purposes). The ASF Factors from the Basel Liquidity Paper are:

2.8 The Basel III Liquidity Regime: The Treatment of Shari’ah-Compliant Banks

The Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision of the Basel Committee (GHOS) in January 2013 stated that the GHOS recognizes that:

Shari’ah compliant banks face a religious prohibition on holding certain types of assets, such as interest-bearing debt securities. Even in jurisdictions that have a sufficient supply of HQLA, an insurmountable impediment to the ability of Shari’ah compliant banks to meet the LCR requirement may still exist. In such cases, national supervisors in jurisdictions in which Shari’ah compliant banks operate have the discretion to define Shari’ah compliant financial products (such as Sukuk) as alternative HQLA applicable to such banks only, subject to such conditions or haircuts that the supervisors may require. It should be noted that the intention of this treatment is not to allow Shari’ah compliant banks to hold fewer HQLA. The minimum LCR standard, calculated based on alternative HQLA (post-haircut) recognised as HQLA for these banks, should not be lower than the minimum LCR standard applicable to other banks in the jurisdiction concerned. National supervisors applying such treatment for Shari’ah compliant banks should comply with supervisory monitoring and disclosure obligations.

These supervisory and disclosure obligations include:

- A clearly documented supervisory framework

- A disclosure framework

This recognition of Shari’ah banks compliance issues is very welcome and is an important step towards incorporating Shari’ah banks into the Basel regulatory framework. It is, however, not sufficient for Shari’ah banks to be fully compliant with many jurisdictions liquidity frameworks. It is to be hoped therefore that the following statement by the GHOS also points to central banks eventually allowing Shari’ah compliant central banks’ deposits.

The GHOS also agreed that, since deposits with central banks are the most—indeed, in some cases, the only—reliable form of liquidity, the interaction between the LCR and the provision of central bank facilities is critically important. The Committee will therefore continue to work on this issue over the next year.

2.9 The Impact of Basel III Implementation

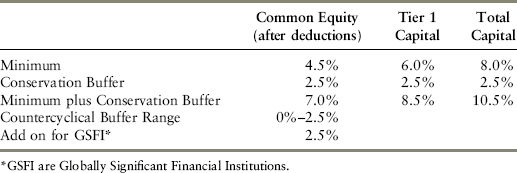

As previously stated, one of the main features of Basel III consists of raising the quality and quantity of capital that banks hold against their risk weighted assets. Under Basel III, the capital requirements are established according to Exhibit 2.1.

EXHIBIT 2.1 Basel III Capital Requirements

The table shows that Basel III relies heavily upon the bank having equity capital, which must include a minimum of 4.5 percent which can be supplemented by other capital that can absorb losses without the bank being put into liquidation (“going concern” capital) of 1.5 percent (some forms of contingent convertible capital) and other capital (“gone concern” capital such as subordinated debt in the case of bankruptcy) of a further 2 percent.

As banks should not run at their regulatory minimum of capital, a further 2.5 percent equity buffer should also be added to the capital requirement. This buffer may be used, but only with the agreement of the applicable regulatory authority and subject to constraints, including restrictions on the bank’s distribution of dividends to shareholders and payments of bonuses to staff.

A number of regulatory authorities believe that banks’ capital requirements should be counter-cyclical (i.e., that banks should build up capital in good economic times in order to provide an additional buffer should the economy deteriorate). A buffer system was in place in Spain under Basel I and II and did prove useful as the economy deteriorated, since Spanish banks by and large had higher capital ratios than those of other comparable countries. The range of additional counter-cyclical capital has been set at 0 percent to 2.5 percent to allow individual regulators to use their discretion in this regard.

Certain financial institutions have been agreed to be either so large and so interconnected (or both) with the global financial system that any problems with them would cause systemic problems. These institutions are known as Globally Significant Financial Institutions (GSFI). These institutions should also hold an additional 2.5 percent of equity.

It is possible therefore for the biggest and most important banks to have a Basel III–based equity requirement of up to 12 percent and total capital of 15.5 percent.

2.10 Timeline

The significant changes required by Basel III will take time to implement, and thus many of the capital and liquidity targets set by Basel III will be implemented over time in accordance with the schedule in Exhibit 2.2.

EXHIBIT 2.2 Phase-In Arrangements

Source: Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

2.11 Stress Testing

Another significant change with Basel III is a greatly increased emphasis on looking at so-called tail risks (e.g., risks with an apparently low probability but a high impact). The understanding of tail risk is especially challenging (see Section 4) and all banks’ risk models must now incorporate regulators’ stress scenarios.

As a result of the changes from Basel II to Basel III, the total capital held by many banks is likely to rise by between four and seven times. Those with large trading books will be especially affected.

3. THE IMPLEMENTATION ENVIRONMENT (SETTING UP A RISK MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK IN A BANK)

Enterprise risk management (ERM) may be defined as a process for managing risk on a firm-wide basis, across types of risk, locations, and business lines. It is an increasingly important template which banks are encouraged by their regulators to use, to implement risk management under Basel II and III regulatory regimes.

There is nothing fundamentally original in the concept of enterprise risk management. Companies and especially banks have been managing their balance sheet risks on a top-down enterprise-wide basis for at least three decades. What is new is that companies now have tools that in many markets enable them to manage their balance sheet risks on a more integrated basis.

These are:

- Risk analytics—which provide a greater ability to understand not only the risk of any one transaction, but the risk of that transaction in the context of all other transactions the company is undertaking. Thus companies can now manage risk to some considerable extent at the portfolio level.

- Risk management products—which allow a company to manage its credit or market risk exposures (e.g., credit default swaps, commodity swaps and options, and interest rate and currency swaps and options. There are also insurance contracts and outsourcing contractors available that make operational risk more manageable than in the past.

The availability of enhanced analytical tools and risk management products has in turn led to new governance structures.

There is no single risk governance structure that can be considered “correct.” The availability of appropriate risk management analytics, data, products, and expertise should all play a role in defining the appropriate risk governance structure for any bank.

The key objective for any bank is to have a clearly defined and well-executed risk governance structure that allows it to understand and manage its risks. Trying to build a sophisticated ERM-based structure without the products necessary to manage the risks in an integrated manner is likely to prove frustrating. Such a structure may be less effective than simply having a risk committee with a broad membership.

Even in major international banks, many senior managers are rightly concerned that ERM-based analysis can become too sophisticated. Within the banking sector, risk management functions initially came into existence purely as control functions. Recently, however, there has been a trend towards a greater use of ERM in banks.

The definition, interpretation, and implementation of ERM vary from bank to bank, but within any bank’s ERM framework it will usually be possible to identify two fundamental components.

The first component of a bank’s ERM framework is a clearly defined and well-established management oversight of the control culture (the first element in the Basel Committee internal control framework), which includes some or all of the following features:

- The board and senior management articulate a risk management and control philosophy that sets the tone for the risk management culture throughout the bank.

- The risk appetite of the institution is set by the board and senior management.

- Risk is defined to include all of the risks faced by the bank—both financial and nonfinancial, and both internal and external.

- Risks are considered on a portfolio basis—across risk types and across business entities.

- Risk considerations are an integral component of strategy formulation and implementation. Risk considerations are also an integral component of day-to-day activities. ERM involves all personnel at every level, from the board downwards.

The second component of the ERM framework is a risk management process that corresponds to the four remaining elements of the risk management framework. The terminology used to describe the risk process varies from company to company but will in general cover:

- Risk recognition and assessment.

- Control activities and segregation of duties.

- Information and communication.

- Monitoring activities and correcting deficiencies.

Internal audit performs an important role in monitoring ERM. In annual reports, this role is usually described separately from the risk management process—perhaps reflecting and emphasising the independence of the internal audit function.

3.1 Models for the Grading of Credits and Establishing a Credit VaR

As described earlier, individual grading models fall into three main categories, reflecting the work of three famous academics:

Credit Scoring Models

Credit scoring models are based on financial accounting ratios. They come in two main types:

Univariate Models

Credit analysis of potential borrowers has a very long history; anyone particularly interested in this topic should read The First Crash by Richard Dale, published by Princeton University Press, for an excellent description of the financial analysis done by Archibald Hutcheson on the South Sea Company in 1720. It is the earliest documented, substantive, financial ratio analysis we know of.

Hutcheson used financial ratios, combining accounting information and market price information, to judge the value of an investment (in equity and debt) and the likelihood of those investments defaulting. What he did was to look at a range of different financial ratios of the debt to equity and of the cash flow of the company and make a judgement call on what the financial performance of the company was likely to be in the future.

This form of model is known as a univariate model. The resulting “grade” is based on case-by-case judgement; the contribution of each piece of the analysis to the resulting probability of default (PD) or PD/LGD (loss given default) is not disclosed. Indeed, it may not be known, as it may vary based on the individual’s experience.

Such models are still in widespread use today, as any equity broker’s report will evidence, and are very commonly used by banks, especially to make judgement calls on lending to private companies—typically to so-called small and medium enterprises (SME)—but also in personal lending and even in lending to public companies.

Such models are of course very flexible, but this can also be a weakness as the model results (the decision to lend and at what price) are essentially dependent on an individual’s judgement (or typically the collective call of a credit committee for loans above a certain figure).

Multivariate Models

In many banks, models based on Altman’s techniques dominate their loan grading and pricing functions. In particular where credit assessment is more centralised it is common for the bank to use a multivariate rather than a univariate version of these models.

Multivariate models identify financial variables that have statistical explanatory power in differentiating defaulting firms from non-defaulting firms. It should be noted, however, that each version of the model may only be applied to a specific industry or industry within a country-specific context.

The fixed weights given to each variable, which are applied across all applications of the model, may be assessed based on judgement but are more commonly assessed by use of statistical analysis of the most powerful explanatory variables. These models allow the creation of a “score” for each credit which can be converted into a PD.

Financial ratios measuring profitability, leverage, and liquidity are the most commonly used variables.

Whilst such models prove to be useful in practice, there is little economic theory to back the choice of any particular financial ratio in forecasting default.

Expert Systems

Banks have made attempts to embed greater discipline in the results from such models, by using review processes and in some cases by developing “expert systems.” In these, the judgement is formalised as far as possible by the use of ordinal grading (e.g., excellent, good, fair, poor) and a combination of judgemental factors (management expertise, depth of management, speed to market, etc.) as well as categories of financial performance (gearing/leverage, earnings, collateral) and macroeconomic factors (cyclicality, sensitivity to interest rates, etc.), which are combined and the resulting “grades” compared to historic default data.

Most banks will also instigate annual review processes to coincide with the release of new audited financial data. This may result in a regrading of the company’s debt. There may in practice be little the bank can do to reprice the debt or change its payment schedule, as banks often lend for periods far in excess of one year. As we shall see, however, the ability of any model to accurately grade debt over periods in excess of one year is limited. John Maynard Keynes’s aphorism, “the future is not unknown, it is unknowable” is true, and in a real sense the future is more unknowable the further into it we try to look, in that the range of possible outcomes gets larger.

The number of factors considered by these models also can be very large. The number of factors in one such model is over 300, though most research on such models suggests their predictive power is increased only slightly by additional factors once the number of these exceeds low double digits.

Neural Networks

When using large numbers of explanatory variables, these models will usually be built using some form of neural network to “train” the system so that the computer system will devise weights for each explanatory variable based on the best fit of the weights to past downgrade and/or default data. This is, however, an exercise in the application of statistical method, and the resultant weights may not have an economic interpretation. It is also important to test such models against “out-of-sample” data, that is, to ensure that the model accurately predicts default and does not “over-fit” the data by not only predicting accurately defaults that do happen but also predicting large numbers of defaults that do not happen (false positives). This may happen because typically the number of non-defaulting firms considerably exceeds the number of defaulters and the latter may be over-represented in the data used in the model.

Merton Models

Merton modelled equity in a leveraged firm as a call option on the firm’s assets.

The concept behind the model was that if at expiration of the option (usually modelled over a one-year period) the market value of a firm’s assets exceeds the value of its debt the firm’s shareholders will exercise the option to “repurchase” the company’s assets by repaying the debt (or refinancing it), whereas if the opposite were true the shareholders would default on their debt, allowing the lenders to take control of the firm’s assets.

The distance to default (DD) is defined in the model as the number of standard deviations between current asset values and the debt repayment amount.

The higher the distance to default the lower the probability of default (PD).

In this model the PD over a one-year horizon is equal to the likelihood that the option will expire out of the money.

To convert a DD to a PD, Merton assumed asset values were lognormally distributed.

This differs from the commercially available KMV models, which estimate the empirical PD using historic default experience.

Historic evidence shows a firm with a DD equal to 4 has an average historical default rate of 1 percent.

Jarrow Models

Known as reduced form or intensity-based models, Jarrow models view default as a sudden unexpected event (consistent with empirical observations). Defaults occur randomly with a probability determined by the intensity or “hazard” function.

These models use observable risky debt prices in order to ascertain the stochastic jump process governing default.

Credit spread can be viewed as a measure of the expected cost of default (CS = PD × LGD).

Using one or any combination of the models above, once the probability for default for each asset can be computed, then each loan in the portfolio can be valued (often done by using Monte Carlo simulation), which produces a probability distribution of portfolio values. A loss distribution can then be calculated permitting the computation of value at risk (VaR) measures of unexpected loss.

3.2 Connections between Risk Categories

Many banks may start the process of ERM by looking at the way in which some of their businesses or products exhibit strong connections between risk categories, such as commodity market risk and credit risk. Such connections are common; for instance, market risk inevitably brings with it counterparty credit risk.

An understanding of the correlations between different risks within a portfolio, between portfolios and between different risks categories can be a powerful tool for reducing the total amount of risk born by any business.

It is important to recognise that correlations are observations; they do not necessarily imply cause and effect. Moreover, correlations in financial markets in particular are in general conditional—the relationships change depending on where the economy is in its cycle. Such correlations are also dynamic in that they change as a result of potential drivers such as technology or even participants’ behaviour, which can occur with the development of new products or markets.

It is therefore important to maintain a certain wariness in relying on observed or assumed correlations within, let alone across, risk categories.

It is also important to note that this “netting” through correlation between risks as described above occurs after individual risks have been netted to achieve the lowest possible individual risk within each risk category. In this context, much is currently being made of the risk reduction that can occur through the netting of the credit counterparty risk that can be done by moving over the counter (OTC) derivative contracts to exchanges to become exchange traded contracts. This does bring some welcome benefits through standardisation of contracts, better disclosure of market participants business volumes, and overall risk exposures but also concentrates counterparty risk in the exchange itself, which becomes the credit counterparty to every transaction. Ensuring exchanges have appropriate risk control and capital thus becomes a greater issue to regulators and market participants as well as the exchanges owners.

Whilst many concepts in ERM have their origins in portfolio management, it is important not to get carried away with this idea. While any grouping of risks may be characterised as a portfolio, they are as likely as not to be more of a collection of disparate risks acquired, not as a result of deliberate choice, but as an inevitable result the of conducting a business over a number of years.

3.3 Economic Capital

Some companies (notably banks) have developed economic capital frameworks as tools for assessing risk, and have realised benefits in the following areas:

- Risk management—economic capital provides a consistent and comprehensive risk management tool using a common language and measure.

- Capital adequacy—economic capital calculations can be used to determine the level of capital needed to absorb severe losses.

- Risk appetite—the amount of risk that a company is willing and able to take. Economic capital is often used to explain risk appetite as it is linked to the cost of risk (see below).

- Strategic planning—economic capital can be used to take into account the cost of risk when planning future strategy, by making it clearer which alternatives create the most value. It can also be used when assessing the success of existing strategies.

- Performance assessment—economic capital can be used in performance assessment, by evaluating the returns in relation to risk (risk adjusted rate of return).

- Portfolio and product management—economic capital can be used to support decisions in many operational contexts.

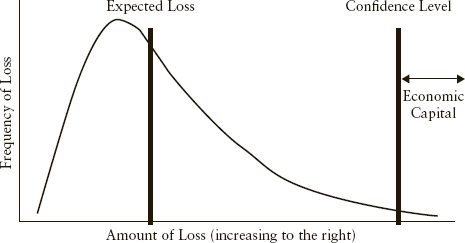

Economic capital is the amount of capital required to absorb severe unexpected losses over a specified period with a specified confidence level.

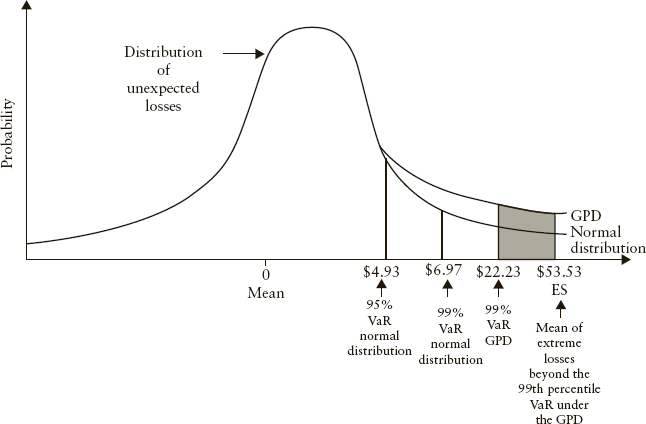

Economic capital is often depicted using charts such as the one shown in Exhibit 2.3. The chart shows the typical distribution of a bank’s losses, with the size of loss indicated on the X axis and the frequency of loss indicated on the Y axis. The shape of the chart indicates that losses will usually be less than the expected (mean) loss, but that occasionally there will be very large losses.

EXHIBIT 2.3 Loss Distribution Illustrating Economic Capital Concept

Expected loss is the anticipated average loss over a defined period of time. Income to offset these losses would normally be factored into product pricing. For example, product margins should cover expected credit losses as well as overhead costs and the cost of unhedged risk.

Unexpected loss is the potential for actual loss to exceed the expected loss, which reflects the inherent uncertainty in the loss estimate. Capital is held to absorb unexpected losses, and the cost of holding such capital should be factored into pricing decisions

The confidence level (or level of certainty) indicates the probability that the economic capital will be sufficient to absorb unexpected losses over a specified time period. It is sometimes interpreted as the risk of insolvency during the specified time period

Tail risk is the potential for actual loss to exceed the estimated unexpected loss according to the right-hand tail of the assumed statistical distribution (the so-called fat tail problem). Capital is held to absorb these extreme losses (losses beyond estimated unexpected loss), and the cost of holding such capital should be factored into pricing decisions.

Economic capital models invariably incorporate correlations in their computation of the total amount of capital required by a bank to support its risks, and the way these calculations operate also invariably reduces the total capital the bank requires to support a given level and structure of business, when compared to a less sophisticated approach to risk management where all risks are simply additive with no (or very limited) allowance for one risk to offset another. It should be noted, however, that these models do not usually incorporate any allowance for “dynamic conditional correlation” between risks, which may significantly increase the contribution of correlations to total risk due to some extreme (usually market wide) event (see Section 4).

4. THE FUTURE RISK ENVIRONMENT

Financial crises have been the main driver in the development of the information systems and financial products necessary to undertake risk management.

Whilst these crises have often originated in financial markets, the lessons have been drawn on by governments, regulators, auditors, and analysts, and have changed perceived “best practice” in corporate governance and risk management.

The continuing crisis from 2007 onwards has brought attention to the dynamic and conditional nature of correlations, and as a result, to the way in which risks that appear to offset one another can in extreme market circumstances reinforce one another. Tail risk can consequently increase as a tail event (crisis) progresses, producing a growing need for capital to support losses as a crisis develops.

Exhibit 2.4 shows such an extreme value distribution (with a fat tail) and can be contrasted with Exhibit 2.5, which shows the type of distribution that results from the application of portfolio-based risk and capital models incorporating dynamic conditional correlation.

EXHIBIT 2.4 Distribution 1

EXHIBIT 2.5 Distribution 2

*GPD stands for Generalised Pareto Distribution. It is one of many distributions that can be used to describe data that exhibits “Fat Tailed” characteristics—a very common feature of price movements in financial markets.

Basel III significantly shifts the emphasis in modelling risk from a simple VaR approach, based on mean variance analysis, to the greater use of stress tests to establish the effect of tail risk (low frequency, high impact, i.e., very unlikely but bad, outcomes) on the bank.

Stress tests form an integral part of internal risk management practices under Pillar 2 and of regulatory requirements, as imposed in the context of the advanced models under Pillar 1, most obviously because Basel III weights trading book transactions in relation to their “Stress VaR.”

The results of the bank undertaking stress tests are documented in particular via the ICAAP and ILAS report, which the bank management submits to the board of directors, and subsequent to the board’s approval these are sent to the bank’s regulator. The stress tests used by the bank will require the approval of the regulator, and in most instances it is likely that the regulator will require banks to submit at least one scenario as laid down by the regulator. An example of this is the way EU regulators have required banks within the European Union to undertake stress tests related, inter alia, to common assumptions on their provisioning against certain EU states’ government bonds.

It is especially important to ensure engagement of the board of directors in the stress testing of the bank, as most regulatory authorities are likely to have greater engagement with bank boards under Basel III to ensure the board understands the implications of the risks the bank runs, the possible effects of stress market events on the bank’s capital and liquidity, and the implications for its business model. Whilst a valid criticism of Basel III is that it does not directly connect in its reporting structures the ICAAP and ILAS, let alone the bank’s business model and the bank’s financial performance, it is likely that many bank boards will require these connections to be made to aid their own understanding.

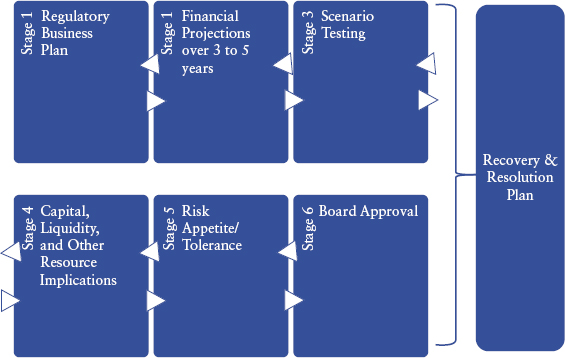

The Exhibit 2.6 shows an integrated process in which the documentation of the board’s strategy and the bank’s business model is reflected in an anticipated budget outturn over the next year and following two years of financial forecasts, the budget/forecast is reflected in capital and liquidity requirements, and then the whole is subject to a series of stress tests to establish the robustness of the projected financial outturn, including capital and liquidity requirements. This form of integrated financial performance reporting has proved very successful in bringing together the board’s strategic outlook and the regulator’s requirements for an enhanced understanding of risk at board level.

EXHIBIT 2.6 The Board Process

Stress tests come in two distinct forms, being based either on sensitivity analysis or on complex scenarios. The former would (for example) encompass the bank’s sensitivity to adverse changes in interest rates, or perhaps to exchange rates, or to downgrades of certain credits or defaults of certain counterparties. They are useful in seeing what specific risks the bank is concentrated in.

Scenarios are attempts to hypothesise a set of events which may adversely affect the bank; an obvious one for a bank with exposure to European markets might be what would happen if the euro area was dissolved or if a certain country left the euro area and reintroduced its own currency.

The importance of a robust programme of stress testing under Basel III cannot be overemphasised, and these stress tests must include what is known as a reverse stress test, which is effectively a stress test to destruction (i.e., to a point where the bank fails to meet its regulatory minimum standards for capital and/or liquidity). The purpose of this test is to identify the causes and consequences that could lead to that outcome.

This reverse stress test is itself, therefore, a basis for regulators to use their powers to require systemically important banks to prepare recovery and resolution plans (often called “living wills”) to ensure that if the bank fails it can be liquidated with the least possible disruption to financial markets and to other banks.

Because stress tests specifically address the effect of extreme events on banks, they can result in the appearance of risk concentrations within a bank’s business that it may not have been aware of. The importance of this is illustrated in Exhibit 2.4, where we see that the dotted line shows a distribution of outturns where very bad results become, past some point, more likely but not less. These so-called extreme value distributions are well known in the insurance business, but have until now not been a common feature in banking. It is, however, not hard to give an example of how such risk distributions can be produced for the banking industry.

Let us suppose you are running a bond desk at an investment bank and that you trade and make a market in both government and corporate bonds. The economy deteriorates and the corporate bonds begin to fall in value as the risk of default is increasing; correspondingly, risk-averse investors buy more government bonds and the value of these bonds rises as investors seek a lower risk investment. Your risk model has corporate and government bonds negatively correlated to each other, which is what you expect to happen. However, the economy deteriorates very rapidly, you can no longer sell your book of corporate bonds, and raising money by offering them as security is very costly, as the funding banks require very large and growing (as the economy deteriorates) “haircuts” on their value. You must fund your book, so you start to sell the government bonds, but you are one of many, and the government bonds now start to fall in price. Note that your risk model is now wrong, as the correlation between the price movements of government and corporate bonds has now turned positive. What was a hedged book has become a very large risk concentration of the bank.

System-wide risk modelling is in its infancy, but it is likely to be one of the major areas of research, policy development, and strategy and product innovation as banks, regulators, and central banks focus on systemic risk.

5. ISLAMIC BANKS AND THE RISK AND REGULATION ENVIRONMENT

Islamic banks and financial markets have been affected by the international financial crisis, but, according to a recent IMF study, they have proven more resilient and less unstable than their conventional competitors.

This means they are also well placed to take advantage of any economic upturn, particularly as the Basel III reforms highlight not only structural weaknesses in conventional banks and financial markets but also the strengths of Islamic finance.

The reforms will also put the two systems of banking on more equal terms in the two critical areas of liquidity and capital structures. However, to take full advantage of these opportunities, the Islamic sector will also have to take other measures, including the development of standardised international products through organisations such as the recently established International Islamic Liquidity Management Corporation (IILM).

5.1 Capital

The Basel III reforms will have a major impact on capital structure by making conventional banks change from a system dominated by equity and more especially debt capital to one in which equity, supported by contingent capital, is the most important element.

At present, Islamic banks are at a competitive disadvantage: Their capital structures are of necessity dominated by equity because they cannot use debt capital, which (when interest expense is tax-deductible) has a materially lower cost than the equity capital. Consequently a conventional bank will offer equity investors a significantly higher return than an Islamic financial institution with a similar balance sheet (and therefore similar total risk). This advantage will be substantially reduced by Basel III, because it will force conventional banks to hold much more equity.

The greater emphasis on contingent capital, a new and not well-understood concept, will also benefit Islamic banks. The few contingent capital structures issued so far are dominated by a form of convertible bond (often called CoCos), where the convertibility “option” is not exercised at the discretion of the bond holder but is mandatory based upon “triggers,” such as a fall in the bank’s equity-to-asset ratio and/or supervisory intervention in the management of the bank.

Clearly the “bond” nature of the CoCos makes them unsuitable for Islamic banks. But contingent capital, as a concept and product, can trace its origins to the insurance industry and specifically to structures that are based on those of an “indemnity fund.” These can be made Shariah-compliant relatively easily.

Such structures, very competitive on cost, feature terms similar to CoCos and hold out the very real prospect of helping to equalise the capital structures of Islamic and conventional financial institutions, thereby making Islamic banks relatively far more attractive to investors by levelling the returns to capital.

5.2 Liquidity

The balance between the conventional and Islamic sectors is also changed by the changes in liquidity demanded by Basel III.

At present, banks have access to funding liquidity based on the bank’s funding structure. If the bank has plenty of stable retail deposits and medium- to long-term funding through bonds, certificates of deposit, or profit and loss sharing accounts, for example, the bank can use these stable sources to fund its asset base, even in difficult economic circumstances. Islamic banks are by and large well-funded institutions, though with very limited capability to transfer their liquidity across national frontiers. This limits their capacity to create rivals to conventional international banks.

Liquidity can also be raised in the market, as a bank can turn its assets into cash either by selling them or by pledging them in order to borrow funds. Market liquidity has grown substantially in recent years, largely due to the growth of so-called repo (repurchase) transactions where banks can pledge assets so they can receive funds.

Conventional banks have been able to take advantage of this market’s growth to fund new business in areas where they have been less able to attract retail deposits or issue debt securities. In contrast, Shari’ah-compliant asset products lack this degree of standardisation, sometimes even within national boundaries, and where national markets have developed they have not been able to support international growth.

To address this problem it is necessary to create international product structures which will lead to the creation of common product features and legal contracts on which asset transfers can be based.

In doing so, however, it should be remembered that the short term nature of repo markets did make them a potentially unstable source of funding—in the recent financial crisis, lenders became unsure of the capability of the underlying assets to be a secure source of repayment for the loans. It should be possible for the Islamic sector to avoid this problem, as transparency and reference to assets with readily observable cash flows are both features of Shari’ah-compliant assets.

While these liquidity and capital requirements under Basel III will benefit the Islamic financial sector, there are nonetheless challenges to be addressed.

The emphasis of some Islamic banks on profit- and loss-sharing (PLS) accounts as a secure source of funding must be qualified. The opaque nature of the “smoothing reserves” held against these accounts is likely to be problematic for bank regulators—who in many countries have fought a long battle to eliminate so-called reserve accounting in the banking industry, which they say is used to smooth reported profits—as well as for accountants, because the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), as implemented, makes it virtually impossible to maintain reserve accounting, at least unless its effects on profits are made completely transparent (in which case it may not serve the banks’ purpose).

These factors may make PLS deposits less attractive to Islamic banks unless steps are taken to reform their structure so as to maintain the stability of their payouts without incurring adverse treatment from regulators and accountants. The reliance on retail funding also tends to lock Islamic banks into their domestic economy. The lack of standardised products internationally, and the often very specific national regulation of Islamic banks, mean that the often-quoted $1 trillion of Shari’ah-compliant “liquidity” globally is something of a myth. In practice, the liquidity is locked into individual national “pools” and there is only a limited capability to move surplus liquidity to countries that may have investment potential but a shortage of funds.

Basel III also stresses the need for banks to maintain a stock of assets that can easily be turned into cash at reliable values either through markets or, should such markets cease to function, through central bank cash from a “discount window.”

The governments of a number of states where Islamic banks are based do issue sukuk, which can provide assets that qualify for discount window access, but a number of countries important to international banks, including the United States and the European Union member states, do not do so.

While these countries will accept as bank stock liquidity some assets issued by AAA-graded countries and a limited number of international institutions (this is complicated in the case of the EU countries by obligations under EU treaties), there is, even so, virtually no sukuk issuance that meets the needs of international banks. The exception is the sukuk issues by the Islamic Development Bank (IDB), which meet the stock liquidity requirements of the UK Financial Services Authority (UK FSA). However, these issues are not very liquid, as banks and investors tend to hold them to maturity.

To address this gap in the market, it is necessary to have liquid AAA-rated government sukuk issued across a range of maturities. This will provide stock liquidity to international Islamic banks (and to domestic banks in countries where there are no government sukuk). And crucially, it will also help create a zero-credit-risk profit rate curve (i.e., a profit rate curve showing different rates for different tenors of funds). Zero (credit) risk yield curves allow conventional banks to price their own credit and that of their customers of differing credit risk quality, by reference to such a curve.

Today, the lack of an equivalent to assess the credit standing of those entities to which Islamic banks advance funds creates problems of pricing credit risk for Islamic banks; and when this is combined with generally illiquid Shari’ah-compliant product markets, the result is that sovereign and corporate sukuk issues trade at what often appear to be illogical prices in relation to their relative credit standing.

Rather than wait for the liquid AAA sovereign sukuk market to happen, there are initiatives that could be taken by those countries with a strong interest in developing Shari’ah-compliant banking and finance, including the development of a strong role for the IILM. Set up though the actions of Bank Negara’s governor Tan Sri Dato’ Dr. Zeti Akhtar Aziz and the IFSB’s then-Secretary-General Professor Datuk Rifaat Ahmed Abdel Karim, IILM’s initial membership of 13 includes, among others. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Luxembourg, and the Islamic Development Bank.

The IILM’s first objective is to issue Shari’ah-compliant financial instruments to facilitate more efficient and effective liquidity management for the Islamic banking industry, and initially will focus on issuing short-term paper in international reserve currencies. This will make a very important contribution to the resolving the problems caused by the separate “pools” of liquidity in Shari’ah-compliant markets.

There do not yet appear to be any concrete plans to build upon the concept of product standardisation and the credit quality assurance it creates. But it is possible to envisage that the standard product definition could be created in a way that could at a later date allow the tenor of the product to be extended. Such a move could also make a potentially important contribution to the lack of the necessary stock liquidity instruments to support Basel III compliance by International Islamic Banks.

5.3 Trade Transactions as Liquidity?

The financing of trade in goods and services and the financing of investments in real assets dominates the provision of finance by Islamic banks. This is due in part to the nature of Shari’ah-compliant finance, which places the funding of transactions in the real economy at the centre of the banking system.

It is also due to the fact that Islamic banks primarily operate in emerging economies where the intermediation role of banks is primarily associated with the provision of capital to trade and industry. If we are to develop and apply global banking regulation to banking systems in both developed and emerging markets across both conventional and Islamic banks, regulation will need to accommodate radically different banking models based on the different roles banks perform within different economies.

Developed markets historically had many of the same characteristics as emerging market economies do today. Their banking systems were developed in support of the financing of trade and industry. Central banks developed their role both as regulator of individual banks within the system and in support of the financial stability of the banking system as a whole. There are a number of practical lessons that can be learned from looking at history. Liquidity, not capital, has historically been the main concern of central banks as regulators and supervisors of the banking system. Historically, banks have failed when they were not able to meet their obligations as and when they fall due.

Ever since the recognition by governments of the need to avoid the systemic risks associated with a bank collapse, the focus of regulatory and supervisory authorities has been on the provision of liquidity to both individual banks and to the banking system.

Basel II has often rightly been criticised for its concentration on bank capital and for subsequently paying little attention to bank liquidity and its management.

Basel III addresses this deficiency, as there is under Basel III an emphasis on the need for banks to maintain a stock of assets that can easily be turned into cash at reliable values through markets and, should such markets cease to function, through central bank cash provision by way of a discount window.

Islamic banks are not alone in having issues with the availability of suitable liquid assets. A number of regulators have working parties on the subject of “additional liquid assets treatment.” Most prominently this involves banks in Australia, the European Commission (on behalf of some non-Eurozone countries) and Hong Kong, where it is felt additional classes of liquid assets will be required.

As the liquidity provider of last resort, a central bank faces a very difficult dilemma if it provides funding liquidity to commercial banks against anything other than government liabilities, as in doing so it creates a potential credit risk for the central bank’s shareholders (their government). Provision of liquidity against the collateral of government liabilities (treasury bills, government bonds, etc.), on the other hand is an easy decision from a credit perspective. A claim against the state is the same credit whether it is a £1 coin or a £1 share of a government bond. Providing £1 coin against the pledge of a mortgage loan from a commercial bank, for instance, is quite a different matter.

This thinking has led central banks and Basel down the path of allowing as “stock” liquidity domestic government bonds, though in the case of the European Union the provisions of the EU treaties have significantly complicated the issue of allowable stock liquidity, even to a point that EU government bonds are allowable across the euro area whatever the credit standing of some EU governments. This fixation with government bonds from a central bank credit perspective is understandable, but if we contrast government bonds with trade bills, the latter have a number of advantages:

- Trade bills are based on self-liquidating trade transactions. They are short term in nature (usually one to three months’ tenor) and thus any commercial bank can easily generate liquidity, even if no rediscount is available, simply by allowing their stock to run off without undertaking new business.

- If rediscount of trade bills is available, then the bank has an incentive to maintain lending against commercial trade transactions, thus encouraging commerce, whereas if only government bonds are available for discount there is no incentive for banks, when their balance sheets are under stress, to maintain commercial lending.

- Central banks, in providing rediscount to trade bills, are taking only short-term credit risk, in contrast to various central bank emergency facilities that have had to involve assets such as longer term mortgage lending.

- In practice, when the Bank of England historically allowed certain (eligible) trade bills as liquidity, it was further distanced from the credit by insisting trade bills be accepted (guaranteed) by a second bank in addition to the originating bank and also by providing funds (by re-discounting the bills) to the discount houses that advanced funds to the commercial banks holding the bills; thus, the discount houses’ capital also provided a “buffer.”

- Many commercial banks naturally originate trade bills as a result of their lending to companies and are well acquainted with the credit involved.

- Trade bills typically pay a rate of interest above a commercial bank’s cost of funds, in contrast to government bonds that pay a rate of interest significantly below a commercial bank’s cost of funds.

It is important also to recognise that the use of trade bills as widely used liquid instruments had a very long history, lasting from the late eighteenth century until Basel I in 1988. They are still in use in Australia.

In the case of Islamic banks, whose access to suitable government bonds as stock liquidity instruments is restricted to only a few domiciles (such as Sudan, Malaysia, Indonesia, and some Gulf countries), there is a strong case for allowing suitably structured trade financing transactions as a form of liquidity provision. Fitting this within the Basel III liquidity regime, as proposed, would not be possible. There is no reason, however, why any central bank could not accept (for the banks it supervises) short-term trade-related instruments (including Shari’ah-compliant instruments) as eligible stock liquid instruments against the security of which the central bank could provide funding. Adapting Basel III to allow such trade financing transaction products should be possible, perhaps through the use of a covered bond–like structure.

The attraction of holding short-term assets when the issuers of bonds may be subject to changes in credit spreads are obvious, as the effect on valuations are much less.

Self-liquidating short-term transactions based on good commercial credits backed by bank credit support (acceptance/covered bond) look more attractive today compared to many long-term government bonds.

The Basel fixation against commercial credit risk may, however, remain a strong impediment to a structure too closely aligned to the old eligible trade bills product.

In this instance, the possible structures emanating from the International Islamic Liquidity Management Corp (IILM), including covered bond–like structures, may be important in creating the required product structures.