Chapter 22

Transparency and Market Discipline: Post–Basel Pillar 3

1. INTRODUCTION

In the wake of the financial crisis that started in 2007, there have been significant developments in the global financial services industry. In particular, the world economies were hit by a major global financial crisis, by most accounts the worst since the Great Depression, which was triggered by the subprime crisis in the United States. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the regulator for the banking industry in the United States, prior to the financial crisis, from 2000 to 2007, a total of 27 banks had failed. Since then, however, a further 412 banks had folded between 2008 and November 2011—a staggering 15-fold increase! The root causes of these failures have been well documented by The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report1 released in January 2011, which, while beyond the scope of the present chapter, is essential reading in order to be able to see the fuller picture.

How did the Islamic financial services industry perform during the financial crisis? Recent studies seem to suggest that, under specific conditions, Islamic banks performed better than their conventional counterparts during and post–financial crisis.2 To date, at least three Islamic banks across the globe have failed. Ihlas Finans House of Turkey was shut down in 2001 due to issues relating to liquidity; Albaraka International Bank in the United Kingdom was closed in 1993 in the aftermath of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BBCI) and ING Baring banking collapses (as well as for other regulatory reasons); and Bank Al Taqwa was shut down in 2001 by the Bahamas authorities, also for regulatory reasons. The closures of all of these banks were independent of the recent financial crisis.

In the wake of the crisis, financial regulators and authorities across the globe have struggled either to tighten existing laws or to enact new ones governing financial institutions, with some taking remedial action more quickly than others. All of these efforts were made with the objectives of enhancing transparency and promoting greater market discipline towards providing a sound and stable financial services industry. The markets need certainty, and the consumers need to feel confident about the markets.

The author is of the opinion that good standards of transparency and market discipline are closely interlinked with good standards of corporate governance. As most of you will be aware, there are many areas of similarity, with regard to corporate governance, between conventional and Islamic financial institutions. You will also be aware that there are some specific corporate governance issues that pertain only to Islamic banks. I do not intend to revisit the subject of corporate governance in any great detail during this chapter, merely to stress the importance of building a firm base of governance in order to help achieve good levels of transparency and market discipline.

It would be as well, in the context of this chapter, to give some insight as to the guiding principles of market discipline applicable to financial institutions in general. Probably there is no better source than members of the Basel Committee themselves, who opine, with respect to conventional banking, that:

The purpose of Pillar 3—Market discipline is to complement the minimum capital requirements (Pillar 1) and the supervisory review process (Pillar 2). The Committee aims to encourage market discipline by developing a set of disclosure requirements which will allow market participants to assess key pieces of information on the scope of application, capital, risk exposures, risk assessment processes, and hence the capital adequacy of the institution. The Committee believes that such exposures have particular relevance under the Framework, where reliance on internal methodologies gives banks more discretion in assessing capital requirements.

In principle, banks’ disclosures should be consistent with how senior management and the board of directors assesses and manages the risks of the bank. Under Pillar 1, banks use specified approaches/methodologies for measuring the various risks they face and the resulting capital requirements. The Committee believes that providing disclosures that are based on this common framework is an effective means of informing the market about a bank’s exposure to those risks and provides a consistent and understandable disclosure framework that enhances comparability.3

In a nutshell, then, the purpose of Pillar 3 is to focus on two key areas: first, to reinforce market discipline through enhanced disclosure, which includes the capital adequacy calculations; and second, to instil market discipline to reinforce minimum capital requirements, to impose incentives for banks to behave prudently, and to promote safety and soundness in banks and financial systems. These principles have been reiterated for application to Islamic banks by the Islamic Financial Services Board’s Guidance on Disclosures to Promote Transparency and Market Discipline for Institutions Offering Islamic Financial Services (December 2007)—see Section 3. Under no circumstances should Pillar 3 be seen as a way to get the market to do the supervisor’s job or, indeed, to get the market to police the supervisors. Let me leave that thought with you there, and I shall return to it later in this chapter.

Section 1 has provided a quick introduction, briefly covering the principles underlying transparency and market discipline as documented in Pillar 3. The rest of this chapter proceeds as follows: Section 2 discusses the compliance status of Pillar 3; Section 3 has been expanded with the inclusion of the role of the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) in view of the significant contributions it has made towards the achievement of a sound and stable Islamic financial services industry; Section 4 provides the conclusion.

2. COMPLIANCE WITH PILLAR 3

What, then, is required of banks to comply with the requirements of Pillar 3? The requirements may be summarised under the following headings in this section:

- Level of Disclosure

- Frequency of Disclosure

- Disclosure Templates

- Basic Principle of Disclosure

2.1 Level of Disclosure

With regard to the level of disclosure, it is mandatory for all banks to disclose at the standard or basic level. Additional mandatory disclosures will be required for those banks taking advanced approaches.

2.2 Frequency of Disclosure

Disclosure should be made every six months via sources that are set by the respective national supervisors. Qualitative disclosures should be made annually. In situations where information on risk exposure is prone to rapid change, disclosure should be made on a quarterly basis. All information provided is subject to verification.

2.3 Disclosure Templates

Templates have been suggested as a means to ensure comparability between banks.

2.4 Basic Principle of Disclosure

Disclosure should be consistent with how senior management and the board of directors assess and manage risks.

Thirteen tables are prescribed in Pillar 3 relating to market discipline and the respective aspects of qualitative and quantitative exposures for each table:

In addition to the above, the Basel Committee’s more recent pronouncements place some emphasis on liquidity risk. The International Accounting Standards Board’s IFRS 7, Financial Instruments: Disclosure also sets out some disclosure requirements regarding liquidity risk, as does the IFSB’s Guidance on Disclosures to Promote Transparency and Market Discipline for Institutions Offering Islamic Financial Services.

While there may be a need to change some of the details in Pillar 3 to adapt to the requirements of Islamic banks, the general direction and relevance of these essential elements of market discipline cannot be denied. They will therefore be generally applicable to the world of Islamic finance. However, like everything else, there are potential benefits and drawbacks to their implementation. In particular, I would draw your attention to the need for a sense of balance between the regulators and the market. Section 3 discusses the Guidance (or Standard) issued by the IFSB pertaining to transparency and market discipline for Institutions Offering Islamic Financial Services (IIFS).

3. TRANSPARENCY AND MARKET DISCIPLINE: SPECIFICITIES OF ISLAMIC FINANCE

This chapter focuses on transparency and market discipline, in tandem with Basel Pillar 3. In particular, this chapter relies heavily on IFSB-4: Disclosures to Promote Transparency and Market Discipline for Institutions Offering Islamic Financial Services (Excluding Islamic Insurance (Takaful) Institutions and Islamic Mutual Funds).4

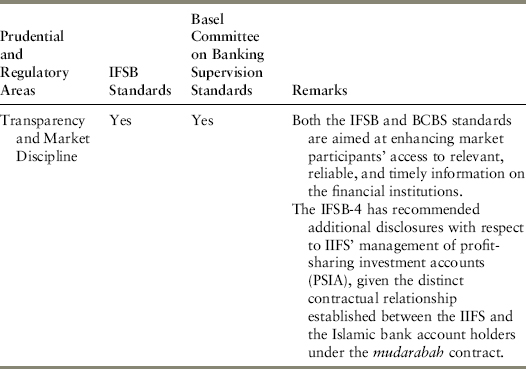

The Standard is designed to specify principles to be followed by IIFS as well as the regulatory agencies in achieving transparency and promoting market discipline. The IFSB Standard has been developed for various types of stakeholders of the IIFS and complemented by the observance of the international standards and best practices. Exhibit 22.1, for example, summarises the similarities between the Basel Pillar 3 Transparency and Market Discipline and that of the IFSB’s Standard.

EXHIBIT 22.1 The IFSB and Basel Pillar III Standards

Source: IFSB, IDB, and IRTI. 2010. Islamic Finance and Global Financial Stability, 60.

The essence of the Standard is the importance of disclosure in promoting market discipline, as well as providing investor protection and creating investor confidence. Thus, to achieve this mandate, the Standard is applicable to both the IIFS and the Islamic window operations offered by conventional banks involved in managing funds in the form of restricted investment accounts. The Standard draws upon the specific features of the IIFS that are absent or not captured in the existing guidelines and principles relating to bank transparency and bank governance issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, and disclosure standards (Pillar 3) contained in the new Basel Capital Accord. The Standard also builds on the standards for Collective Investment Schemes (CIS) and on international accounting and auditing standards.

One of the challenges of implementing this Standard is the nonbinding nature of all the IFSB’s Standards, Technical Notes, and Guidance Notes in various jurisdictions. (The same applies, in principle, to the pronouncements of the Basel Committee and other international standard-setting bodies that rely on national regulators for enforcement.) Thus, the effectiveness of the implementation of these Standards may vary from country to country. However, this particular Standard is not in conflict with the existing international accounting standards and other relevant national standards.

The objectives of the Standard are:5

- To enable market participants to complement and support, through their actions in the market, the implementation of the Islamic Financial Services Board’s capital adequacy, risk management, supervisory, and corporate governance standards; and

- To facilitate access to relevant, reliable, and timely information by market participants generally, and by investment account holders (IAH) in particular, thereby enhancing their monitoring capacity.

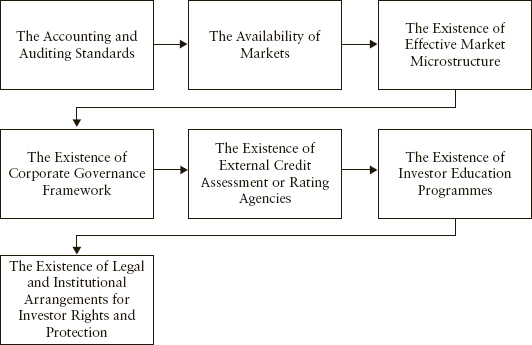

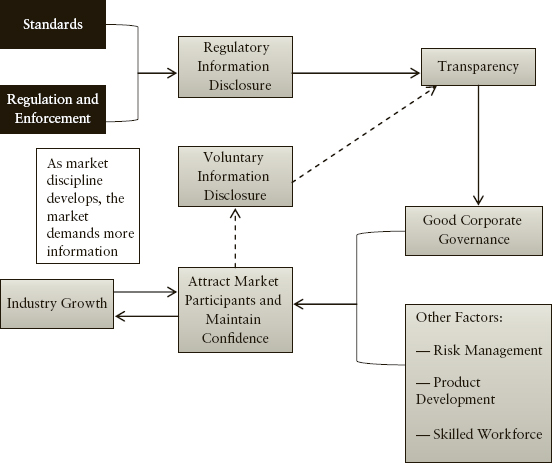

To achieve transparency and market discipline, the financial market needs a well-functioning infrastructure, as illustrated in Exhibit 22.2.

EXHIBIT 22.2 The Infrastructure for an Effective Transparency and Disclosure Regime for IIFS6

3.1 The Islamic Financial Services Board’s Disclosures in Achieving Transparency and Creating Market Discipline

The IFSB Standard on Transparency and Market Discipline can be divided into five broad categories, and for each of these categories there could be Qualitative and/or Quantitative Disclosures. The categories are:

Financial and Risk Disclosure Principles

IIFS must establish internal disclosure policies with regard to the nature of disclosures it will make and the internal controls over the disclosure process. This process must identify the appropriateness and the frequency of the disclosures. The Standard provides guidelines on “comply and explain” basis on the following items:

Disclosures for IAH

An IIFS obtains funds from the IAH under the profit-sharing and loss-bearing mudarabah contract. It is recommended for the IIFS to disclose specific policies, procedures, product design/type, profit allocation basis, and differences between restricted and unrestricted IAH.

The profit-sharing investment accounts (PSIA) are very similar to the collective investment schemes (CIS), thus the available international standards, guidelines and discussions on risk disclosures by the CIS, and on the role of investor education in the effective regulation of the CIS and CIS operators, can be replicated in designing policies for the IIFS.

The disclosures are recommended by the IFSB Standard to be made as part of the periodic external financial reporting process (marked “F”) or as part of product information published in connection with new products or changes in existing products (marked “P”). The disclosures can be classified by the following:

Retail Investor-Oriented Disclosures for IAH

The IIFS is recommended to publish a simplified and uncomplicated financial/annual report for the retail investors. While some of these disclosures might require great detail, they must be presented in nontechnical language. Items proposed by the Standard to be included in the risk-return characteristics of products, such as the restricted and unrestricted PSIA, are:

Risk Management, Risk Exposures, and Risk Mitigation

The purpose of this disclosure is to ascertain the nature of risk to which the IIFS is exposed and the techniques it uses to identify, measure, monitor, and control those risks.

The Standard provides several key financing risks as well as specific risks faced by the IIFS. It is recommended that for each area of risk, the IIFS describes: the risk management objectives, policies, and practices; the structure and organisation of the relevant risk reporting and measurement systems; the measures and indicators of risk exposures; policies for hedging and/or mitigating risk; strategies and processes for monitoring the continuing effectiveness of risk management tools; and techniques such as hedging and other risk mitigants.7

General Governance and Shari’ah Governance Disclosures

Other than for the purpose of establishing general and Shari’ah governance processes, structure, and function of such governance in an IIFS, the primary objective of the disclosures is to ensure transparency regarding the status of Shari’ah compliance.

In strengthening the IIFS in the wake of the recent global financial crises, the IFSB and the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) published a joint report entitled Islamic Finance and Global Financial Stability in April 2010. The report identified the following eight building blocks to strengthen the infrastructure and framework of the Islamic financial services industry.15

“Market discipline” refers to the use of the market as a means of governance, as a complement to regulation and supervision. The potential benefits and drawbacks of this approach are set out in Exhibit 22.3.

EXHIBIT 22.3 Potential Benefits and Drawbacks of Market Discipline in Islamic Banking

| Potential Benefits | Potential Drawbacks |

|

|

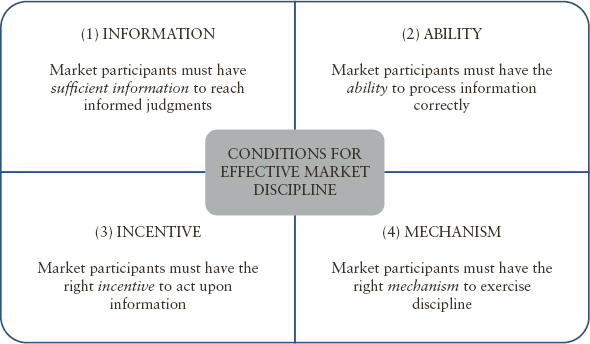

I would also like to reiterate some thoughts developed by Andrew Crocket, former Bank for International Settlements general manager, on the conditions necessary for effective market discipline (see Exhibit 22.4). These thoughts are equally applicable to the world of Islamic banking, which is in the context of market discipline, very similar to conventional practices. First, information: market participants must have sufficient information to reach informed judgments. Second, ability: market participants must have the ability to process information correctly. Third, incentive: market participants must have the right incentive to act upon information. Fourth, mechanism: market participants must have the right mechanism to exercise discipline. All four prerequisites will need to be developed in order to achieve effectiveness. However, the focus at this point in time should be on the first two conditions, without which we cannot move on to satisfy conditions three and four. Let me elaborate a little on the first two conditions.

EXHIBIT 22.4 Developing Market Discipline in Islamic Finance

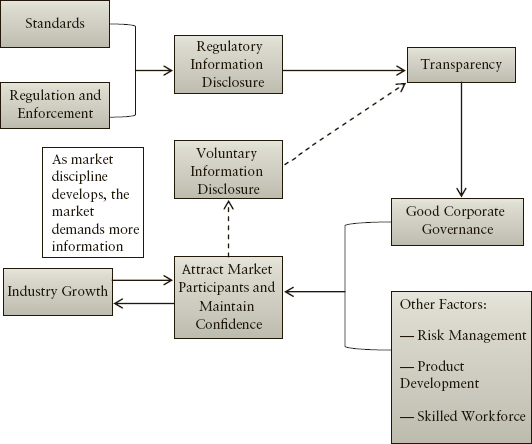

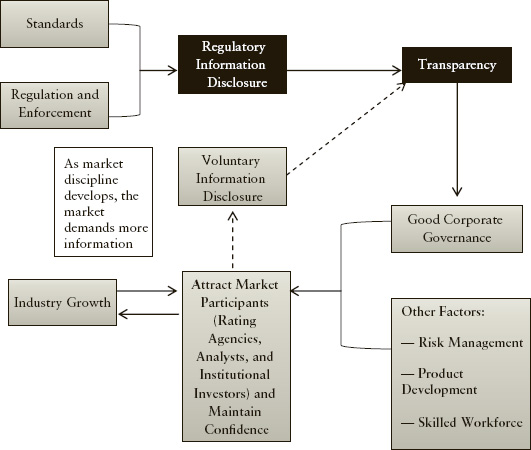

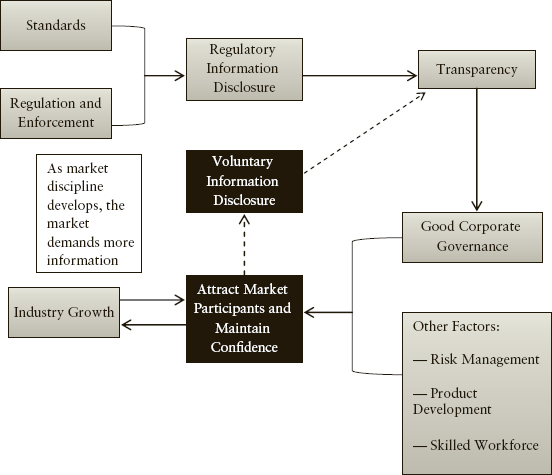

Earlier in this chapter I indicated that I would return to discuss further the purpose of Pillar 3. You will recall that I highlighted that the purpose was not to get the market to do the supervisors’ job and not to get the market to police the supervisors. At this juncture I should like to introduce the concept of a “virtuous cycle of transparency.” This is a cycle that embraces all aspects of regulation, disclosure, transparency, corporate governance, market discipline, and the growth of the Islamic banking industry. Exhibit 22.5 illustrates the cycle.

EXHIBIT 22.5 Transparency: A Virtuous Cycle

Let me first examine the role of regulators in this context (see Exhibit 22.6). Initially, standards need to be set. Here we already have Pillar 3 developed by the IFSB. The standards will need to be adopted by the local regulators on a country-by-country basis (central bank or equivalent). In this role of standard setting, the regulator(s) set the wheels of market discipline in motion by developing coherent regulatory disclosure requirements which the markets should find useful, both on a national and international basis. Enforcement would most likely come at the country level, whereby the central bank would enforce regulations by monitoring the implementation and compliance of Islamic financial institutions to the disclosure requirements. The regulator also needs to demonstrate vigilance; in particular, there is a need to be vigilant about negative signals sent by the market, as this may be an early warning of distress in individual institutions. Timely involvement by regulators may help to prevent or minimise the occurrence of bank failures.

EXHIBIT 22.6 The Role of Regulators

Let me now examine what constitutes good information disclosure and lends itself to enhancing transparency in the marketplace. The board of directors and senior management of Islamic financial institutions must be committed to providing good information disclosure, both quantitative and qualitative, which meets the criteria of useful, accurate, complete, and credible.

Under the category useful, the information required depends on what the market discipline is aiming to achieve. For example, if the objective were to demonstrate to the market that the bank is performing satisfactorily with adequate profitability, then financial statements and comparative analysis would be useful information. If the objective is to demonstrate good risk management, then information on how the bank is managing its risk exposures is pertinent. If the objective were to demonstrate Shari’ah compliance, then Shari’ah certification in the annual report and accounts as well as a description of the Shari’ah review programme would be of great assistance. If the objective were to demonstrate a resolution of the conflict regarding investment account holders (IAHs) resulting from the dual fiduciary role of the bank, then information pertaining to both the asset allocation and profit allocation of the bank would be extremely useful.

Under the catergories accurate, complete, and credible, it is necessary that the information is all of the foregoing so that the market may be confident in using the information. This may be achieved by means of using external parties—for example, auditors, and ratings agencies—to verify the information provided. In addition, the information should be material, be provided on a timely basis, and be easily available to the public. Here the use of the Internet, by using the bank’s website, is of great importance. Furthermore, the provision of the information should not be unreasonably burdensome to the bank, especially the smaller ones. Finally, the information disclosed should not be, as far as possible, proprietary, which would endanger the competitive position of the bank. In this respect, adequate generic information should suffice (see Exhibit 22.7).

EXHIBIT 22.7 Criteria for Good Information Disclosure

Let us now take a look at the role of the market participants in this “virtuous cycle of transparency” (see Exhibit 22.8). Here I see two main roles. First, there is the role of disciplining institutions, where each market develops a reputation for rewarding and punishing institutions based on information disclosed to provide an incentive for good behaviour. Reward good institutions by giving them good ratings and placing funds with them, and punish deviant institutions by doing exactly the opposite.17

EXHIBIT 22.8 The Role of Market Participants

Second, there is the role of soliciting information, whereby the market relays the information needs to the financial institutions. Over time, as market discipline develops, the potential for voluntary information disclosure, based on market demand, also increases.

4. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The Islamic finance industry has already demonstrated that it has the products and infrastructure to compete with conventional financial institutions. Annual growth rates are significant; in many markets, they are far outstripping the growth of conventional banking. However, further growth may be hampered if standard setters and regulators do not grasp the opportunity to move the industry forward by working together in implementing a strong and practical corporate governance framework, incorporating elements of global best practices.18

To date, the overall performance of the IIFS during and post financial crises, namely the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997–1998 as well as the subprime and global financial crises, is encouraging. As noted by the Governor of the Central Bank of Malaysia, Tan Sri Dr. Zeti Aktar Aziz, “the global financial crisis has had limited direct effects on Islamic finance. While Islamic finance by its very nature only engages in transactions that have underlying tangible productive activities, the slower overall growth and the increased uncertainties have affected pricing and activity in certain market segments. However, this in part reflects the shift in activity from the financial markets to the Islamic financial institutions.”19

As discussed previously, a good corporate governance framework will promote transparency via information disclosure by institutions that must be credible. This will help to inspire confidence in the marketplace, promote market discipline within the industry, and ultimately serve as a catalyst to grow the industry and take it to the next level. Long journeys start with small steps, and we do not have a moment to lose!

NOTES

1. Released by the U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission on 27 January 2011.

2. See for examples, Parashar, S.P., and J. Venkatesh (2010). “How Did Islamic Banks Do During Global Financial Crisis?” Banks and Bank Systems 5(4), pp. 54–62; and Hasan, M., and J. Dridi (2010). The Effects of the Global Crisis on Islamic and Conventional Banks: A Comparative Study. IMF Working Paper no. WP/10/201.

2. Bank for International Settlements (June 2006). Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Part 4: The Third Pillar – Market Discipline, in International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards, p. 226.

4. The IFSB-4, www.ifsb.org/standard/ifsb4.pdf.

5. IFSB-4, Disclosures to Promote Transparency and Market Discipline for Institutions Offering Islamic Financial Services (Excluding Islamic Insurance (Takāful) Institutions and Islamic Mutual Funds), 2007, 1.

6. Ibid., 30–34.

7. Ibid., 16.

8. IFSB-1, Guiding Principles of Risk Management for Institutions (Other than Insurance Institutions) Offering Only Islamic Financial Services (IIFS). December 2005, 6, www.ifsb.org/standard/ifsb1.pdf.

9. Ibid., 19.

10. Ibid., 25.

11. Ibid., 23.

12. In a mudarabah contract, the mudarib is the entrepreneurial partner who uses the capital belonging to the rabbul-mal as the capital provider.

13. IFSB-2, Capital Adequacy Standard for Institutions (other than Insurance Institutions) Offering only Islamic Financial Services. December 2005, 19, www.ifsb.org/standard/ifsb2.pdf.

14. IFSB-4, 26.

15. See Islamic Finance and Global Financial Stability, 41–48.

16. The Banker, Top 500 Islamic Financial Institutions 2011 (www.thebanker.com/Reports/Special-Reports/Top-500-Islamic-Financial-Institutions-2011), and author’s own estimate.

17. It should be noted that IAH would have a very limited role in disciplining Islamic banks (see Archer, S. and R.A.A. Karim, “Corporate Governance, Market Discipline and Regulation of Islamic Banks,” The Company Lawyer 27, no. 5 (2006), 134–145.

18. The IFSB has already started this process by issuing its various standards, guiding principles etc.

19. Governor’s Keynote Address at State Street Islamic Finance Congress 2008, Boston USA—“Islamic Finance: A Global Growth Opportunity Amidst a Challenging Environment.” Boston, October 6, 2008, www.bnm.gov.my/index.php?ch=9&pg=15&ac=285.