1

What to Do When You Can’t Predict the Future

You may have wondered why so many things seem to be harder and take longer to accomplish than you would like—and why both those things seem to be increasing.

We don’t have the answer in every case, but here is an explanation that probably covers the majority of situations: the way we have been taught to solve problems was designed for a different world. To deal with uncertainty today, we need a different approach.

YOU’RE SMART, creative, and terrific at approaching challenges. So why does it seem that the number of things you can’t figure out is increasing? The problem may not be you. It could be the way you were taught to think. From kindergarten on, we’ve all learned prediction reasoning—a way of thinking based on the assumption that the future is going to be pretty much like the past.

Demographics are one simple example of how prediction reasoning (what we refer to as Prediction) works. You can calculate, with a some confidence, the world population in 2050 because you know a lot of things. Here are just four:

- You know how many people are alive today: about 7 billion.

- You know how those people are distributed by age, that is, you know how many teenagers there are, how many people over age sixty-five, and so on.

- That means you know how many people are in their twenties and thirties, when most people decide to have children.

- And you know recent trends in population growth, which is slowing as people worldwide are, on the whole, deciding to have fewer kids.

Studying all this data and much, much more, you can, as the United Nations did recently, say with reasonable certainty that in the year 2050, there will be 8.9 billion people on the planet. Armed with that data, you can also make a number of fairly accurate estimates, such as how many diapers will have to be produced, how many gallons of water those 8.9 billion people will drink each day, and how much the United States will need to pay out in Social Security benefits at the midpoint of this century.

We have gotten really good at Prediction. To support this kind of thinking, we have developed great analytic tools (statistics, probability theory, computer simulations, and the like). These tools are logically sound and complete. That’s a scientist’s way of saying they yield the correct solutions, and the same solutions, every time. Math like this is great. It has right and wrong answers, and is consistent. It allows us to do wondrous things. You want to send a rocket to the moon and land at a specific spot (even though the orbiting moon will be moving while the rocket is underway)? No problem. Prediction allows you to do that. Need to come up with a fairly precise estimate of how many sports cars will be sold during a recession? Prediction can help with that as well.

Because it works so well in these kinds of situations—and countless others—we (like you) became accustomed to using Prediction all the time. And like anything, if you do something over and over, it becomes a habit. Your view of the world becomes conditioned.

And yet... Not everything can be foreseen (and therefore predicted). Want to know if the cute guy across the hall is going to ask you out? Sorry, Prediction can’t help. Desperately need to know if the town council is going to accept your idea of turning Main Street into a pedestrian mall, before you spend your nights and weekends working on the project? Prediction is of little use. Is the world ready for your brand-new, never-before-seen product or service? That’s another place where Prediction really does you no good.

Here’s the central point of this book: when the future is unknowable (Is quitting your job and starting something new a good idea? Will the prototype we are developing at work find a market?) how we traditionally reason is extremely limited in predicting what will happen.

You need a different approach.

We are going to give you a proven method for navigating in an uncertain world, an approach that will complement the kind of reasoning we have all been taught. It will help you deal with high levels of uncertainty, no matter what kind of situation you face. We know it works because entrepreneurs—the people who have to deal with uncertainty every day—use it successfully all the time.

If it works for them . . .

When people write about entrepreneurs, they invariably focus on their behavior: what Howard Schultz or Michael Dell did in building their companies. If you take that approach, you probably would conclude that every single entrepreneur is unique, so there is little to be learned from studying them; you would have to be Howard Schultz to start Starbucks and Michael Dell to start Dell.

Enter our friend Saras D. Sarasvathy, professor at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business. (We are huge fans of Sarasvathy’s work. To connect with what she has written, see the Further Reading section at the end of the book.) Early in her work, she made a fascinating discovery, one that ran counter to the conventional wisdom. Sarasvathy studied serial entrepreneurs, people who have started two or more companies successfully.

But instead of looking at the behavior of entrepreneurs—which is indeed unique—Sarasvathy focused on how they think. There she found amazing similarities in how they reasoned, approached obstacles, and took advantage of opportunities. Yes, of course, there were variations. But the basic approach, as she understood it, was always the same.

In the face of an unknown future, entrepreneurs act. More specifically, they:

- Take a small, smart step (see “What’s a Smart Step?”) forward;

- Pause to see what they learned by doing so; and

- Build that learning into what they do next.

This process of act, learn, build, as we came to think about it, repeats until entrepreneurs are happy with the result, or they decide that they don’t want to (or can’t afford to) continue. At about this same time Sarasvathy was pursuing her research, the faculty at Babson started going down the same path and came to many of the same conclusions.

Inspired by all the research, we began to extend it in a variety of ways. We tested our ideas with colleagues and held more than two dozen seminars at which we invited smart, skeptical people to challenge our framework’s conclusions. They helped us refine and clarify our thinking, but our central findings only grew stronger as they told us about their experiences, which reinforced what we had learned.

So, we began to wonder if the way entrepreneurs think would work for the rest of us. Before moving on, we want to note a couple of things about that statement.

First, while we will use many business examples throughout the book, we will also be providing some that come from everyday life. This is not a business book in the traditional sense. (See “What You Won’t See in This Book.”)

Second, when we set out to see if the way serial entrepreneurs think would work for everyone, we weren’t looking to replace Prediction. There were two reasons we weren’t.

- As we have seen, Prediction works really well when the future can realistically be expected to be similar to the past, and since we are advocating smart steps (see sidebar), it certainly isn’t smart to discard something that works well in a specific situation.

- Sarasvathy’s research—which we will refer to throughout—shows that entrepreneurs continue to use Prediction effectively in the situations where it works well, that is, in the places where it is logical to assume that the future will be a lot like what has come before.

So, we were not looking to replace Prediction. Rather, we wanted to know whether the logic entrepreneurs employ when they face the unknown—we came to think of it as Creaction—would work for everyone else when the future is essentially unknowable. In other words, we wanted to know if Creaction could be used to complement Prediction in everyday situations that we frequently find ourselves in (“Can I convince the town to add a bicycle lane downtown?” “Will anyone buy what I have to sell, if I start a company?” “Would I be happy chucking it all to join the Peace Corps?”)

We found that the entrepreneurial logic works in business and potentially elsewhere. You can use this way of thinking to complement the kind of reasoning you have already been taught—an additional way of thinking that can help you deal with high levels of uncertainty no matter what kind of situation you face.

What are we are talking about?

What exactly is Creaction? Well, to start, it is based on acting and creating evidence, as contrasted with thinking and analysis.

Here’s one way to think about that pivotal difference. A dancer dances. Substituting thinking for dancing doesn’t work. If all you do is think, you end up just thinking about dancing. There is nothing to show for that thought.

Thinking is often a part of creating, but without action, nothing is created. This is true for even very intellectual, cerebral fields. For a task to be considered creating, you must publish, teach, or whatever. Daydreaming by itself is not creating.

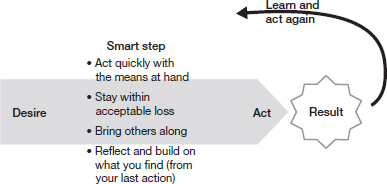

How does Creaction play out in practice? How does it help us deal with uncertainty? The process has three parts, which repeat until you have reached your goal or decide you no longer want to. (See figure 1-1.)

FIGURE 1-1

Creaction: How to act in uncertainty

- Desire.Find or think of something you want. As we will discuss in chapter 2, you don’t need a lot of passion; you only need sufficient desire to get started. (“I really want to start a restaurant, but I haven’t a clue if I will ever be able to open one.”)

- Take a smart step as quickly as you can. As you will see, a smart step has its own three-part logic as well.

- • Act quickly with the means at hand—i.e. what you know, who you know, and anything else that’s available. (“I know a great chef, and if I beg all my family and friends to back me, I might have enough money to open a place.”)

- • Stay within your acceptable loss. Make sure the cost of that smart step (in terms of time, money, reputation, and so on) is never more than you are willing to lose should things not work out.

- • Bring others along to acquire more resources; spread the risk, and confirm the quality of your idea.

- Build on what you have learned from taking that step. Every time you act, reality changes. If you pay attention, you learn something from taking a smart step. More often than not, it gets you close to what you want. (“I should be able to afford something just outside of downtown.”) Sometimes what you want changes. (“It looks like there are an awful lot of Italian restaurants nearby. We are going to have to rethink our menu.”) After you act, ask did those actions get me closer to my goal? (“Yes. It looks like I will be able to open a restaurant.”) Do you need additional resources to draw even closer? (“Yes. I’ll need to find another chef. The one I know can only do Italian.”) Do you still want to obtain your objective? (“Yes.”) Then act again and again until, building on what you learned, you have what you want (or you have decided you don’t want it or you want something else instead).

Researchers found that successful entrepreneurs used a common logic that allows them to deal with situations in which the future is unpredictable. What works for them will work for you.

In other words, when facing the unknown, act your way into the future that you desire; don’t think your way into it. Thinking does not change reality, nor does it necessarily lead to any learning. You can think all day about starting that restaurant, but thinking alone is not going to get you any closer to having one.

Déjà vu all over again?

Sometimes, when we explain the concept of Creaction, people say it sounds familiar. It should; it was the way we all learned—at first.

When you were a child, everything was unknown or uncertain, so you started learning through action. You’d make a sound and something happened; your mother responded. You pulled the cat’s tail and got scratched. So, what we advocate amounts to the recovery of a skill we all had a long time ago: the ability to act your way into better thinking.

Remember, Creaction complements Prediction. When Prediction makes sense, predict. When it doesn’t, think about using Creaction.

As you deal with a new situation, you will invariably bounce back and forth between the two. That is exactly what you should do. In fact, we have a term for the process of using both forms of reasoning: Entrepreneurial Thought and Action. That’s our phrase for using both Prediction and Creaction together to solve a problem or create something new.

About the journey ahead

As you have already seen, we are big believers in practicing what we preach. We continued that approach in how we constructed this book. We will:

- Help you take small, smart steps.

- Pause to review what you’ve learned, and then

- Move ahead, building on that knowledge.

You have just started part I, “What to Do When Facing the Unknown,” which deals with the two foundations of Creaction: uncertainty, in chapter 1, and desire, in chapter 2.

In part II, we will cover the four individual elements that make up the logic of Creaction, and in part III, we will show in detail how to apply Creaction in certain situations (in large organizations or with family and friends). We will conclude by coming full circle and explain how entrepreneurs have proven this method works—not only for them, but for all of us. You will find that discussion in chapter 10 and the epilogue.

That’s all there is

There you have it. That’s our book in a nutshell. We set out to answer one simple question: what do you do when the way you think doesn’t allow you to thrive in today’s brave new world? We think we have developed an answer that will allow you to succeed in the face of uncertainty.

If you have insufficient data, make your own.

If you find the idea appealing, in the pages ahead, you will find a detailed description of how to use Creaction in all kinds of situations you may encounter at work and in your personal life.

If you don’t, well, you found out how the approach works. You took a small step into the unknown (learning about Creaction) and decided it’s not for you. That learning was worthwhile, too.

Incidentally, although there is tons of research that support the ideas and arguments we will present (see the Further Reading section at the end of the book), if you get some value out of this book, it will not be because we convinced you with these arguments. It will be because what we have to say resonates with what you already know. It will strike you as common sense. To find out if it does, turn the page. The journey is about to begin for real.

Takeaways

- When the future is unknowable, how we traditionally reason is extremely limited in predicting what will happen. You need to complement the way you were taught to reason with a new kind of thinking: Creaction.

- Creaction does not replace prediction reasoning; it works with it. One is not necessarily better than the other (it depends on the circumstance), but using them together is a very effective prescription.

- If Creaction feels familiar, and it should, that is because it is the way we reason naturally. All we are advocating is rediscovering a skill you already have.