6

Bring Other People Along

Having a large pool of people who can help make your vision come true is a wonderful resource. That’s why you want to view everyone as a potential customer or collaborator. How can you enroll people in your idea and what can you do with them once you have them onboard? Let’s see.

PEOPLE WHO WANT TO DISMISS Creaction out of hand, for whatever reason, tend to say: “This is nothing more than ready, aim, fire.” But the real summary is: “Aim. Fire.” There’s not a lot of getting ready.

What we have been saying in the first five chapters is that when you are in a situation where you don’t know what is going to happen next, and the cost of acting to find out is low, then fire with what you have at hand or what you can assemble quickly.

We have seen that serial entrepreneurs usually don’t spend a lot of time doing traditional research. They prefer to discover if there is a market or audience for what they want to do by going out and asking people if they want to buy. That’s the only way to know for sure and it is consistent with their desire to be grounded in reality.

Serial entrepreneurs certainly don’t do a lot of competitive analysis. In one study, some 74 percent reported they are not concerned with competitors, or that they consider potential competitors irrelevant until they know if there is a market for their idea.

But one place where they say they spend a lot of time—and they urge you too as well, whether you are starting a new company or anything else—is in trying to get as many committed people as they can to enroll in their efforts early on. Having self-selected, committed stakeholders join you is a way to spread the risk, confirm that you have a worthwhile idea, obtain additional resources, and have more fun. Serial entrepreneurs told Saras Sarasvathy that they believed that the growth of their potential enterprise was limited only by the number of collaborators they could attract, not by how much money they could raise.

Because bringing others along is such a big idea, it is worth spending some time exploring it. First, we’ll put what we are discussing next in context. Then we’ll give you a proven approach so that you can enroll others yourself.

Tangible exchanges

If you’re starting a business, the thing you want most is sales. Entrepreneurs passionately believe that. They start selling as soon as they can. Maybe they have a prototype. Maybe it’s only a specification sheet. They simply don’t wait for a polished product unless they have to.

Instead of worrying about being attacked from the outside by competitors, people who employ Creaction try to strengthen their base. One way to do that? Attract committed stakeholders who share your values and can build on and help you refine your vision.

This is still good advice even if you’re not starting a business. If you have a new idea for a community center, for example, you’ll want to find out if you have support, before you invest too much time and effort (and ideally those people will join in your effort.) Getting into the market early (to see if there is a “buyer” for your idea or someone who shares your desire) lowers your cost and spreads the risk. Moreover, having potential buyers (a consumer or partner) tells you that they like your idea and confirms that you’re on a good track. It builds your confidence and credibility with others, which is an asset we discussed in chapter 5. When you are thinking of starting something new, you want to do an inventory of your assets. Attracting self-committed stakeholders clearly falls into the “who do I know” category; it is another way of expanding the means you have at your disposal.

Many of us have aspirations that exceed the assets we have at hand. By adding self-committed stakeholders, you are accumulating additional resources. The knowledge network and assets these people have can be added to your own. That’s no small thing, since very few of us have the wherewithal and/or abilities to start something completely from scratch.

Of course, some people prefer to go it alone. A friend of ours in the construction business started as a framer and bootstrapped himself to the point where he is now constantly building six new homes at a time. He is worth millions, and he owns 100 percent of his business. He took an extremely long time to get to this point, because he financed everything himself. He was willing to take 100 percent of the risk in exchange for 100 percent of the gains. But he is not most people. The vast majority of successful entrepreneurs we know bring others into the process early on. Babson College research shows there are fewer and fewer examples of entrepreneurs going it alone.

Co-creation

The committed stakeholders who join you will help change your original idea, if you bring them in early enough in the process. They end up being collaborators and taking ownership of what is created. They become, in the very real sense of the word, co-creators. The initial vision becomes shared, it expands, and it becomes “ours” instead of just yours.

As you scale up, you will bargain and negotiate with the people who join (this is not a bad thing; they are smart and have good ideas), and as a result move from “me” to “we.” As in, “we want to do this going forward” instead of “this is what I want to do.”

Because of this addition, the process you will go through in creating something new will look like this. As you get these committed stakeholders—these are people who have actually invested money or other resources; they are not those who have only graced you with their advice and opinions—to join, you should take their input and suggestions into account without regard to possible stakeholders who may or may not join later. In other words, the people who are there today determine the course of the venture. It’s likely that some people will come along later, and your product, service, or idea will be less appealing to them because of the actions you have already taken and so they will not want to join. So be it. You are operating in the here and now.

Of course, the people who are involved with you employ their own understanding of acceptable loss to decide how much they are willing to risk in your venture. You need to keep that in mind. While it is certainly possible that they will contribute significant amounts of assets (money, time, contacts) to your venture, the odds are that their investment will be far less than yours. Like you, they are going to contribute according to what they want and can afford, and your venture may not be the most important thing going on in their lives.

Interactions with other people who make commitments yield new means and, in many cases, new goals. This process iterates as you keep adding self-selected stakeholders and continues until you reach the point where the new customer’s requirement would stretch your product too far, either technically, financially, or you simply don’t want to make any more changes.

Can there be a problem with involving too many stakeholders? Absolutely. If they are the ones with the money, they could try to take you in a different direction than you want to go (“I know you want to do X, but I am only going to provide the money if you modify X”). All those competing voices, ideas, and personalities can make moving forward a whole lot like herding cats. Either you learn to manage this situation—there are entire books on the subject—or you decide to do something else.

Getting the most out of stakeholders

To make sure you achieve the maximum benefit of adding committed stakeholders, remember that:

- Everyone should be focused on current reality. Your immediate goal should be taking the next smart step toward what you want to accomplish and not focusing on what could happen.

- Everyone is a potential stakeholder until proven otherwise (by saying no), but only people who commit get a say in shaping the outcome. Others just get to express an opinion.

- Everyone commits only to what he or she wants and can afford to lose, not what is calculated to reach goals. If someone has committed $1,000 to help you, but you need $5,000, don’t browbeat him into providing the additional $4,000. Find it elsewhere. Acceptable loss for others is different than it is for you. Acknowledge that and move on.

- As more commitments are made, goals become constrained and solidified to the eventual point that new members must more or less take it as they find it. At some point, it becomes too late to dramatically alter the product, service, or idea being considered.

Intangible exchanges

By now the idea of obtaining additional self-selected, committed stakeholders probably appeals to you, so let’s turn our attention to how you gain the commitment of others. For this, we need to look at something that, while related and often commingled and confused with selling, is quite different. We’re talking about enrollment.

Enrollment is not about getting somebody to do something that you want them to do. It’s about offering them the chance to do something they might want to do (in this case, becoming part of your effort). You don’t convince them. They truly convince themselves. So, it’s about enabling them to put their own name on the roll of the people who are going to be involved with you. It’s generally to your advantage to have as many people committed to (enrolled in) your project as possible, even if none of them are prospective buyers or users of what you want to create.

How you get that enrollment to happen is a pretty straightforward process.

Where do you begin? Step 1. Be enrolled yourself

You can’t expect to gain the commitment of others if you’re not committed yourself. You must want to make your idea a reality. Starting anything new is hard enough if you are committed. If you are not, you raise the degree of difficulty exponentially. Others can sense if you are not enrolled. They can tell you are not excited about the idea or truly committed to making it happen. And if they get that feeling, they are bound to ask, “If she is not really into it, why should I be?”

If you try to enroll someone when you are not truly enrolled yourself, you end up selling, and you probably won’t even do a very good job of it. As we will see, selling and enrollment are different things.

Step 2. Honesty

Okay, you are truly committed to the idea. Now you want to get people to come along. What’s the next step? You talk to anyone and everyone about what you want to do. And you are genuine and transparent. You give them a complete picture. Not only do you tell them the positives and negatives, to the extent you know them, you also tell them why your idea is so important to you. If it is because you want to make a lot of money, tell them. If it really is all about making a small part of the world a better place, say that. Remember, one of the results in enrolling people is a lasting relationship. You do all of this because you want first and foremost an authentic relationship on which to build trust and joint action. You can only build this kind of meaningful relationship if you are being forthright.

What you are hoping for is that people will enroll with you and be inspired to take action. One of the first actions you want them to take is to tell you what they think of your idea. If you’re sitting there talking to someone about what is really important to you, it is natural to want to know if what you are excited about rings his chimes; you want to know if it did anything for him. You want to hear something back!

If the response is negative, or not what you hoped, that’s fine. All that means is that you are at a dead end (at least as far as the enrollment process goes with this person). It’s far better that you know early on. What you don’t want is to continue to expect enrollment when it clearly doesn’t make sense for him.

By contrast, when you have your sales hat on, and you will need to put your sales hat on, you want to get the potential customer to buy as well as enroll. The best salespeople are honest, but it is a functional kind of honesty. They are truthful about what their product or service does, but they accentuate the positive, especially the product’s (or service’s) financial advantage and how it fits the customer’s needs. If they mention shortcomings, they both minimize them and put them in the best possible light.

However, getting people to enroll requires a deep honesty about aspirations and values. It’s generally not about functionality or money. People enroll with you, perhaps even more than with your vision. That’s why you tell the complete truth. And they will either join you or not. That is just the way it goes. There’s nothing you can do to get someone to enroll. When you try, you’ll invariably become manipulative and start selling your vision. The person you are trying to sell will see right through it. People can immediately sniff out when you are trying to get them to do something, even if it is in their best interest. There is no reason to go down this road when what you are looking for is genuine commitment to your cause. People either want to enroll or they don’t.

Let’s suppose the person you are talking to gets excited. Well, of course, this is a good thing, but often only part of the equation. Yes, she may be excited for you. She may be happy that you have found something that feels right for you. But it does not mean that she is willing to join you. She will enroll only when what you have talked about connects to a desire within her. And the deeper the connection between what you are talking about and what is important to her, the more likely she is to put her shoulder to your wheel alongside you. And, fortunately, that happens fairly frequently. When it does, you end up discussing what is important to both of you. At that point, your vision clarifies and actually changes, even if only a bit, to become our vision. (For an example of how one organization handles the issue of enrollment, see the discussion of Willow Creek Community Church in the box, “Enrolling Believers.”)

Step 3. Offer action

You will notice that an integral part of the enrollment process is to immediately offer the person who wants to join you some real work to do, no matter how small. There aren’t open-ended commitments, such as “I will get back to you.” That is the equivalent of thinking, not doing. As we said, there are many roles in enrollment, and you can propose a big part or a small one—depending on people’s needs and yours. But an immediate offer is to your advantage and theirs so that you can take action together. When that action occurs, you know the enrollment has really taken place.

The difference between selling and enrollment (and by the way, you need both)

If you are selling, you are trying to persuade, convince, influence, sway—whatever word you want to use—someone to do something you want them to do. You want someone to buy what you have.

Honest selling is a noble profession. Great salespeople can make your life easier when you are looking to buy. But while a great salesperson wants you to be happy, her ultimate focus is on getting you to do what she wants: buying. Her goal is to make the sale, a transaction of real things (her goods or services for your money).

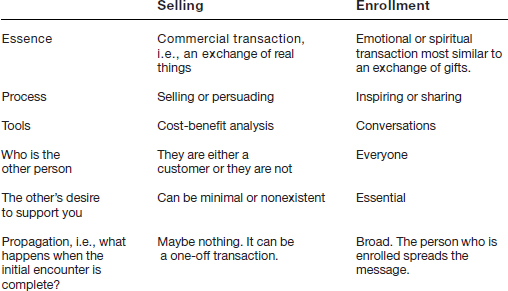

In contrast, when someone enrolls, it is because you have inspired him to act in favor of what he wants to do. It is an exchange of intangibles. You can’t buy anybody’s commitment. You can buy his product—and he can buy yours (and again, that is perfectly legitimate)—but you can’t buy commitment. He becomes part of your efforts because he is excited by your dream and wants to join you. The essence of enrollment is that your efforts become his efforts as well. (The differences between sales and enrollment are shown in table 6-1.)

TABLE 6-1

Differences between selling and enrollment

That’s the key distinction between enrollment and selling. Ultimately, you want both. Sales without enrollment yield a customer. That is good, but perhaps it is a missed opportunity (the customer might have spread the word about you). Enrollment without a sale creates ambassadors. That’s good, too. But could you have ”taken their order” as well? When you have enrollment with sales, you have a home run.

Here’s an example, involving an unlikely source: QVC, the online shopping channel, where the on-air “talent” tries to sell you merchandise.

The hosts are not scripted, because the network wants the sales pitches to be as friendly and authentic as possible. In preparation, the network puts presenters in a room where they get to play with the merchandise; they are given the demographics of who the product is likely to appeal to and then they’re asked to figure out a way to sell it. One of the most effective salespeople, bar none, was a former high school Spanish teacher, Kathy. How she sold computers will make our point.

QVC had failed miserably when it first tried to sell computers, back when personal computers were just being introduced. Like everyone else, it had tried to sell computers on the basis of capabilities—bits and bytes, storage, and the like. Unless someone truly understood how the machines worked—and let’s face it, most of us didn’t, and still don’t—he was not going to plunk down $2,100 for a machine based on its specs.

Kathy took a different approach. At the beginning of her hour, she walked onto the set with a sealed box. Inside, she said, was exactly the same computer you would receive if you ordered. She more or less said, I am your friend, Kathy and over the next half hour I am going to explain to you how I realized this computer is one of the most important things you can have in your life.

As she began talking, a man walked onstage and began to take the computer out of the box. She introduced him and said, Steve is going to put the computer together while we talk. You will see the hardest thing about getting the machine up and running is getting it out of all the packaging.

Then Kathy began discussing the product. She started by saying she knew nothing about computers. But what she did know was that there was an entirely new world you could connect to if you had one. (As an aside, Kathy as you will see is also a great master at establishing acceptable loss and helping people act quickly.)

She had this thing beautifully timed. She talked about what computers could do, stopping every once in a while to talk to Steve to underscore how simple the set up was. At the twenty-seven-minute mark, there was a computer booted up and fully functioning, and the camera zoomed in so you could watch her surfing the QVC Web site.

Her viewers said, “Wow, Kathy just did this. I can do this.” In the next half hour, Kathy basically reviewed what she had done, and by the time the hour was up, QVC had sold millions of dollars worth of computers with virtually no returns. That was millions in sales simply by creating a fundamental relationship of authenticity coupled with selling. She was authentic. She talked about how she was a novice. And she showed every step in the process.

Just Start:

An Exercise for Enrolling People

Rewrite your desire as if it were fully accomplished and successful. What would it look like and feel like?

For example, say your desire is to throw a great party. In this case, your description might be: It’s the end of the party. Guests are exhilarated and exhausted from laughing. People have grown closer. Some are actively planning a repeat event.

Tell a friend or someone else what you want to do, but spend most of your time describing what it will be like when your desire is fulfilled. Then ask, “Do you have any ideas to help? To make it better? People you might know who can help or contribute?”

Takeaways

- Enrollment is getting people to buy in and be excited along with you. It’s a voluntary, personal commitment on their part.

- Selling is getting someone else to do something that you would like him or her to do.

- You want both. Sales without enrollment creates a customer, and that’s fine. Enrollment without a sale creates people who talk positively about what you are trying to do. That’s good, too. But when you have both, à la Kathy at QVC, truly remarkable things happen.