Chapter 9

EXTRACTING KNOWLEDGE VALUE USING DOCUMENT MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

Snapshot

Electronic document and record management systems (EDRMS) are increasingly seen as a way to effectively and efficiently store vast arrays of documents. From the perspective of improving access to knowledge in the organization, such information repositories are clearly potentially valuable in supporting better knowledge flows. Yet, the promise that such systems offer is often not fulfilled. By pinpointing precisely where value typically lies and identifying proven ways to extract it, the return on the investment in electronic document management can be significantly improved.

Intelligent EDRMS use means linking the technical ability to store, locate, and connect information with processes and approaches that tap into the unstructured knowledge in people’s heads. This provides essential context and meaning to a situation and is a source of real value to the organization.

We found three potential sources of value generation from the effective EDRMS: compliance, competitiveness, and collaboration. Although, for most organizations, one of these is likely to be the primary value driver, all three need attention. The key is to determine an appropriate balance for your context. Implementing EDRMS needs to be viewed as a significant change programme. The factors that are known to underpin the flow of knowledge (motivation, skills and abilities, actions and the environment) point to the issues to be addressed through the change programme. In all cases, training, communication, and leadership are particularly important. Additionally adjusting work practices and building in learning mechanisms to evolve the system as conditions change are also essential. These factors are all captured in a maturity model to help establish a peer learning approach to delivering knowledge value from an EDRMS.

Why this Matters

Why do they need to make me use (the system)? It must be because it’s not much good. If it was any use I would use it anyway. Why do they have to force me to use it? They haven’t convinced people of the value of the system.

This was the jaded response of one EDRMS user.

Millions of pounds and thousands of hours have been invested in the development and implementation of electronic document and records management systems (EDRMS). They promise seamless and effective Information Management that will lead to huge return on investment from efficiency and effectiveness gains. The reality for many companies is rather different. EDRMS are effective as repositories and often produce some efficiency savings but all too often they do not form part of the productive, active knowledge flows that helps businesses innovate, flourish, and grow in the way many managers hope.

Bringing a knowledge perspective into the implementation offers the potential of greater value generation. However, it needs individuals to be actively engaged with the system, rather than simply instructed to use it. We came to describe this as a requirement for “intelligent usage”, which is evident when individuals are thinking about how to use the system to make better decisions in their own jobs, as well as what the possible knowledge needs of others might be in the future.

What this Means for Your Organization

In an EDRMS, “documents” is a broad description that includes audio files, video files, textual-based files, spreadsheets, photographs, CAD drawings, and PDF files, amongst others. In overall business terms, documents can also include non-digital media such as paper, microfiche, film, and video tape – all of which can now be scanned and incorporated into an EDRMS as digital files. Here, we use the term document interchangeably with the term record, although we recognize that there is an important distinction to be made in some situations.

“For us, the benefits revolve around collaboration and competitiveness. We’re sharing knowledge around the organization – and we’re saving time, money and paper.”

Cathy Blake, whilst Head of Knowledge Management at PRP Architects

There are three main ways in which EDRMS can be used to improve organizational performance: compliance, collaboration, and competitiveness.

- Compliance is about governance, auditability, and control.

- Collaboration is about improving connectivity and communication between people.

- Competitiveness is about organizational efficiency improvements.

Although there is likely to be a main purpose for your system, paying appropriate attention to all three “Cs” will mean that it can generate even more value for your organization. Our strongest recommendation from the research was that you need to understand what each of the Cs means in your organization, what the balance needs to be between them, and then design your system and implementation plan accordingly. Table 9.1 expands on the potential sources of value from each of the three “Cs”.

Table 9.1: Sources of value from an EDRMS

| Compliance | Collaboration | Competitiveness |

|

|

|

Compliance: Organizations using an EDRMS to support compliance with external regulatory requirements or internal standards tend to use it to collate information from various sources into an organized structure. Parallel preparation and reviewing is used to produce new documents. This means that there tends to be increased confidence in decisions because the thinking that led to the decision is more visible, decisions can be made based on up-to-date information, and the transparency of the process improves individual and organizational learning for the future.

Collaboration: Organizations using the EDRMS to encourage collaboration tend to use the system to support collaborative working on documents and to encourage people to search the repository to discover who had worked on topics of interest in the past, then to contact them for more detail. In some cases, the system is also made accessible to customers to support closer working relationships. As a consequence of improving collaboration through using the system, knowledge flows more freely across organizational boundaries, increasing understanding of how the various activities of the business fit together and allowing faster decision-making.

Competitiveness: Organizations seeking to improve their efficiency (competitiveness) through the EDRMS tend to encourage users to re-use rather than re-develop materials. This requires that information be stored in a consistent way so that it can be found by others at a later date, despite possibly having a different purpose to that of the originator. Efficiency gains come from the re-use of previous experience and effort. The additional benefit of having organized and accessible information is that decision-making is improved by having a greater evidence base to draw on, reducing the need for individual judgement and thereby reducing risk.

Creating an Action Plan

Imagining knowledge as a life-giving fluid flowing around the organizational arteries is a useful metaphor. To successfully deliver results, it has to flow efficiently and deliver effective nourishment from where it’s created to where it’s needed. Technology, processes, and people either enhance or block the flow. Implementation involves concentrating on how you can enhance the flow of knowledge into the “reservoir” of the EDRMS and then on to another user. Building on work that looked at how to enable more effective flows of knowledge around organizations (see Chapter 2 for more details) you can ask a series of key questions to better understand this process:

- Is there the right environment for the EDRMS?

- Does the EDRMS facilitate the right actions by users?

- Do people have the right skills and knowledge to use such a system?

- Are people motivated to use the system?

- Are people aware of the knowledge potential and business benefits of using the system?

It is important to recognize that EDRMS implementation is a major change management project and should be treated as such. The reality is that often organizations are relatively fragmented, rather than single joined up structures. There can be a resistance to change as a result of either excessive stability in the past, or fatigue from never-ending change. Culture change always takes more time than you would expect. We have identified five important factors that need to be developed together in a holistic and integrated way to underpin effective implementation.

“IT is only part of the solution. It’s important to put in the right culture as well, in order to get ‘buy in’.”

Andrew Sinclair-Thomson whilst Assistant Director at the Department of Trade and Industry’s knowledge management unit

Leadership: Leaders must demonstrate how specific use of the system makes a difference to what matters in their part of the organization. The leadership style that may be most effective is:

- Work with others to create a vision and direction.

- Help others see why things need changing and why there’s no going back.

- Share the overall plan of what has to be done.

- Give people space to do what needs to happen, within business goals.

- Seek to change how things get done, not just what gets done.

Training: There is a spectrum of expertise amongst users, even when the system has been in place for a while:

Power user/expert user/super user: font of knowledge in how to use the system.

Specialist user: expert in using the system for a particular purpose.

Everyday or regular user: can use the common functionality of the system.

Laggard: doesn’t have the skills needed to use it properly.

Resistor: thinks “filing is not my job” and gives it to someone else to do.

The reality is that a lack of knowledge and skill about how to use the system produces laggards. Many systems are not easy to use to start with. One user said: “You know, when I think I’ve grasped it, I then have a few days without using it and I’ve lost it, I have to re-educate myself.”

- Usability and end-user requirements must be at forefront of the design process. Make sure the system is as simple as possible to use.

- Training needs significant attention – more than you imagine. Be creative in the ways that people can learn how to use the system and get support when they have problems. Manuals are not sufficient – people are reluctant to use them. Train local super users who are interested and willing to help others. Extensive and comprehensive training programme and materials are needed (including floor-walking helpers, games, surgeries, and best practice guides).

- Ensure an adequate level of computer literacy (the current level may be lower than you imagine).

Communication: Knowing that the system is there, how it can be used, and the difference it can make in achieving organizational objectives contributes positively to EDRMS usage levels. Clear and consistent communication is important. When we heard one system referred to as an electronic filing system in an organizational communication, we were not at all surprised to hear one interviewee saying that he does not use the system very much because “filing is not my job”.

To move forward:

- Promote the benefits of the system regularly and often, until well after the initial launch.

- Celebrate success stories where the system has been used to improve business performance.

- Manage expectations; do not raise them too high, keep them realistic.

“It’s important to recognize that the technology is only a means to the end, and not an end in itself.”

Nicholas Silburn, Research Fellow, Henley Business School

Changing the way work is carried out: You also need to think about how the system relates to working practices and other initiatives. An EDRMS requires a critical mass of people to use it before it can be successful. A culture change is required: a shift from paper to electronic working and publishing work-in-progress instead of keeping it private. Getting the most from an EDRMS means a different way of working and thinking for most people, which takes time and effort to achieve.

- “Join up” collaboration initiatives by relating the EDRMS implementation to work and business processes and cultural change.

- Consider how to move to running the organization on real-time information from the system, rather than emailed and personally stored information.

- Decide which documents and records support knowledge processes that have the most value to the organization and try to remain focused on these.

Building in mechanisms for feedback and improvement: It is likely that the value delivered by the EDRMS will gradually be eroded if it is not updated to reflect feedback from users, as well as to respond to changes needed by the business. Mechanisms to manage the system on an ongoing basis are essential to sustaining value generation.

- Ensure that the system can evolve as the business changes.

- Put users at the centre of the development process.

Self-Assessment Using a Maturity Model

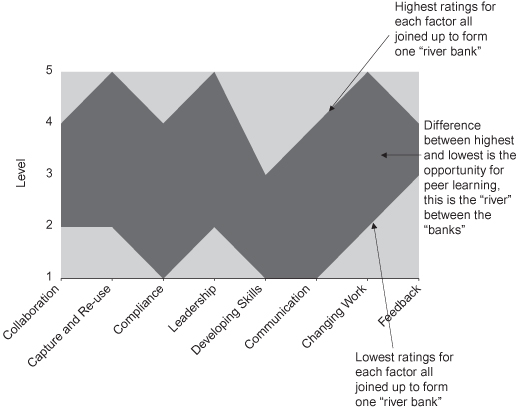

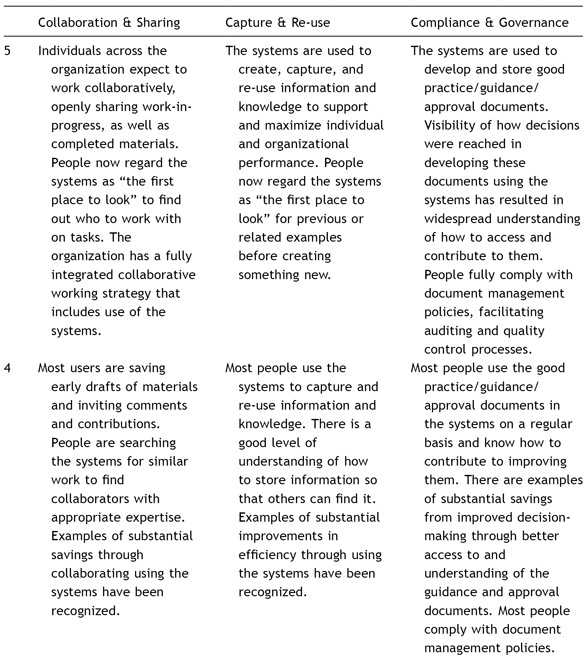

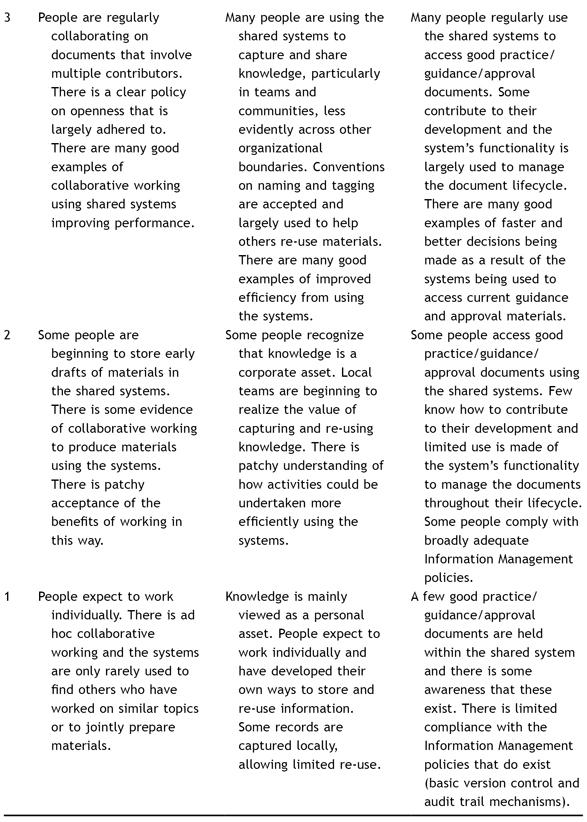

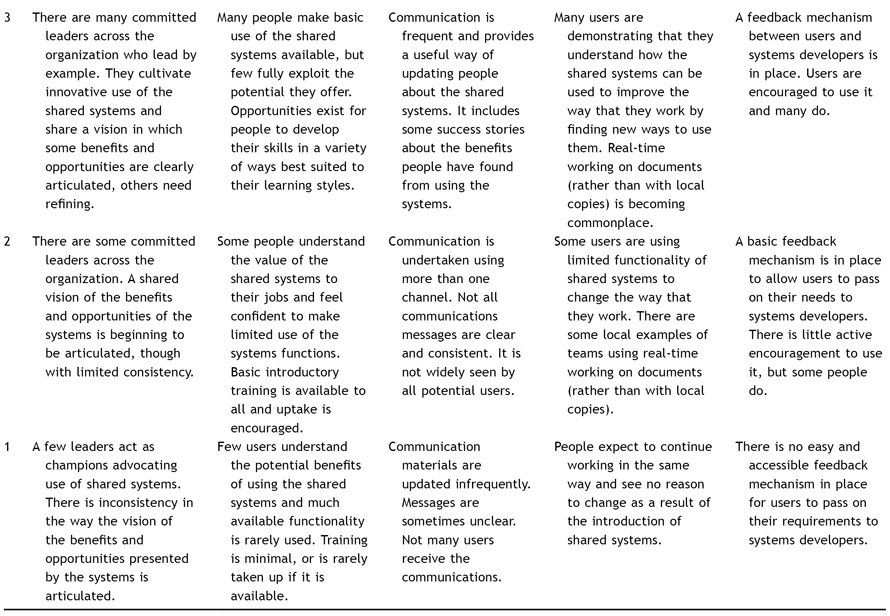

A maturity model for the three factors that ensure that you achieve value from the system and the five factors that enable it to be used effectively allows you to assess the strengths and weaknesses of different parts of your organization and facilitate knowledge sharing between them. The two parts of the maturity model are shown in Tables 9.2 and 9.3. Using this as part of a peer learning process is a very effective way to build organizational capability. The steps you could follow to use this maturity model are as follows:

1. Identify a group of people representing different parts of your organization (different teams, activities, or functions). At least six would be good, 10–12 is probably the maximum. Invite them to a 1.5–2 hour workshop.

2. At the start of the workshop give everyone a copy of the model and talk through what the eight factor headings mean so everyone has a similar understanding.

3. Ask them each to rate their team/group/activity (as appropriate) for each factor according to the 1 to 5 level definitions.

4. Then ask people to identify where they would want to get to on each factor within the next few months (identify the gap between the current and desirable rating).

5. Ask them to pick the two priority areas they think would make the most difference if they were to move from where they are to where they want to be within that time.

6. Collect the information and use a flipchart to represent who has what rating (the River Diagram shown in Figure 9.1 can be a useful way of showing the overall picture). Add in the desired ratings and what the priorities for improvement are (maybe in a different colour).

7. Look at who is strong at each factor and who wants to improve on it. Connect these people so they can discuss what the strong group is doing and how the weaker group can learn from this. These “peer assist” conversations should ideally be started at the workshop, then encouragement given for them to continue afterwards.

Figure 9.1: River diagram showing EDRMS maturity model factors

More details about how to use an extended version of this approach are available in the book Learning to Fly.1 You may also choose to introduce a company or knowledge programme view at the end if you have other options to offer people who want to make improvements on particular factors.

Table 9.2: EDRMS maturity model part 1: delivering value

Table 9.3: EDRMS maturity model part 2: making it work

Some hints and tips for getting the most from the peer learning process:

- Encourage people to start at the bottom (maturity level 1) and work up, rather than the top and work down when they are deciding how to rate their part of the organization.

- You may decide that three months is too short a timeframe for improvements in your organization. More than 18 months is unlikely to be helpful though in relation to EDRMS change programme.

- There will be a lot of discussion about what the eight factors mean for your organization. This is fine, as long as everyone understands and agrees with the final interpretation.

- The most value will be gained if you can repeat this process to track progress over time. This should be a productive learning process though, rather than a control and performance measurement process. A learning approach encourages collaborative conversations and peer learning, bringing all parts of the organization up to their highest desirable levels.

- The discussion is the most useful part of this process – allow time for it and encourage it.

Real Life Stories

Implementing an EDRMS As a Change Management Programme – DTI (Department of Trade and Industry)

The UK’s DTI (since renamed Department for Business, Innovation and Skills) completed implementation of an EDRMS in March 2003 for about 5,000 staff in its HQ offices in London and 19 locations around the UK. The name given by the DTI to the project and EDRMS was “Matrix” and the project was completed on time and under budget. An excellent start, if regarded as just an IT project. However, the main challenge involved changing the culture (that is, working habits and attitudes towards managing information). Right from the initial planning stage this project was recognized as being more about the “management of change” than implementing an IT system and as a consequence, emphasis was placed on involving end-user staff, communication, and training. In addition a new “information manager” role was created in every work unit to support the new work processes.

On implementation, the DTI’s policy on Information Management changed from “the official business record is paper stored in paper files”, to “the official business record is electronic stored in electronic folders in Matrix”.

The Government Department’s remit was wide ranging and staff generally worked in small teams and mostly on policy matters. For many years staff had become used to saving emails in their own MS Outlook folders and draft documents in the personal drives of their PCs. Documents considered part of the business record would be printed and filed in paper folders, mainly by junior staff. Changing these working habits and long held attitudes to private stores of electronic information was the main challenge in ensuring full adoption of Matrix.

During the rollout of Matrix, the central team drove the project forward in partnership with local work units. However, once the system was implemented it was clear that ownership of the working practices and delivery of benefits should be taken up by the managers in local work units. To achieve this, a panel of senior staff, representing the main areas of DTI’s remit, was formed. Known as the “Departmental Matrix Change Panel” (DMCP) and chaired by a DTI Board member (the Director General of Legal Services), its role was “Championing increasing and intelligent use of Matrix”. To achieve this it had a four-pronged strategy.

1. Increasing Matrix usage by DTI HQ staff

2. Increasing skills and competency

3. Developing and sharing best practice

4. Developing new ways of working.

The DMCP used league tables, peer pressure, and awards to increase motivation, bite-size refresher training to improve skills, sharing good practice to illustrate actions required, and leadership to change the culture and working environment. Leadership proved to be the most significant factor. It is worth noting that the DMCP activities needed to integrate with other major initiatives during a period of significant business change, which included reducing staff numbers.

By March 2006, having achieved significant growth in usage (over 82% of staff using Matrix), DMCP decided to hold an event on 16 May 2006 to recognize and award people who, through their efforts and ideas, are helping to increase DTI’s operational effectiveness and to publicize good practice. This event was called the “MOSCARS” an acronym of:

![]()

Over 100 nominations were submitted with stories that illustrated good practice in using Matrix or in encouraging better practice that resulted in some benefit or added value for the Department. The winners were selected by a panel of internal and external judges.

Top Tips

Some points to bear in mind inc09 relation to the system are:

![]() Bring in a corporate governance perspective to drive good practice in helping others retrieve information.

Bring in a corporate governance perspective to drive good practice in helping others retrieve information.

![]() Aim for effective but balanced governance (for example, standardized tags on each document – including author’s contact information – but avoid being too bureaucratic).

Aim for effective but balanced governance (for example, standardized tags on each document – including author’s contact information – but avoid being too bureaucratic).

![]() Think about key system requirements: reducing document duplication, consistency of approach to using the system, effective search function, common look and feel, proper version control.

Think about key system requirements: reducing document duplication, consistency of approach to using the system, effective search function, common look and feel, proper version control.

![]() Be clear about the access requirements of the system – who should be able to access the information and what will be their needs? Avoid blanket provisions.

Be clear about the access requirements of the system – who should be able to access the information and what will be their needs? Avoid blanket provisions.

![]() Think about how best to communicate with people about the system, accepting that everyone has different preferences about receiving information. Use Chapter 16 to help you tailor more effective messages.

Think about how best to communicate with people about the system, accepting that everyone has different preferences about receiving information. Use Chapter 16 to help you tailor more effective messages.

Communication was identified as one of the key implementation factors, so we developed a “Highway Code” metaphor that you could adopt as part of your communications strategy shown in Box 1.

The Research and the Team Involved

This project was carried out by a working group of knowledge managers from member organizations of the Henley KM Forum. Public and private sector organizations were included and academics also participated. It was carried out during 2005 and 2006 and was based on interviews with 16 users of EDRMS in four organizations, together with pre-implementation user surveys in three other organizations. The intention was to help knowledge managers engage in productive dialogues with colleagues about how the EDRMS can really add value by tapping into and enabling essential flows of knowledge across the organization. It is not intended to provide prescriptive advice for a particular business.

Box 1: The EDRMS “Highway Code”

For improved collaboration – “car share” and “stop, look, listen”:

- Collaborate, don’t duplicate.

- Use the system to prepare and review documents in parallel with others.

- Before creating a document, stop and see if it has been done before, look in the system, and listen to others.

For improved competitiveness and effectiveness – “keep the tank topped up”, “see and be seen”, and “become an advanced driver”:

- Keep the information in the system current.

- Make it easy to find the information that you contribute.

- Having the right information always available makes it easier for people to cover for one another.

For improved compliance – “clunk, click every trip” and “one careful owner”:

- Maintain the integrity of information you work with through regular reviews.

- Keep information organized and in one place.

Finally: “We know a man who can”:

- Contact your expert users and the systems administrators if you need further help.

The Project was co-championed by Nick Silburn and Dr Christine van Winkelen of Henley Business School and Andrew Sinclair-Thomson of the Department of Trade and Industry. The working group included representatives from:

Davis Langdon

Defence Procurement Agency

Department of Trade and Industry

GCHQ

GlaxoSmithKline

Metronet Rail

MWH

Nationwide Building Society

Nissan Technical Centre Europe

PRP Architects

Unisys

Particular thanks are due to Mark Lawton who carried out the interviews as part of his MBA studies.

Final Reflections from the Research

Balancing integration and differentiation has been described as a dilemma all organizations must face.2 This is the challenge of finding the optimum balance between drawing on different perspectives and knowledge bases to make sense of and adapt to a changing world, and being able to integrate these effectively in a coordinated and efficient way to enable a coherent pattern of effective decisions that achieve the purpose of the organization. We saw EDRMS being used to control activities (compliance), draw on different sources of knowledge from across the organization (collaboration), and reduce inefficiency in the coordination of the business (competitiveness); effectively all attempts to deal with the issue of organizational integration and differentiation in an efficient way. These very real tensions need to be considered by those implementing EDRMS.

- Collaboration is helped by just enough compliance in the form of sufficient standardization to allow efficient sharing of materials. Yet collaboration is also stifled by over-bureaucratic and highly regulated systems that achieve compliance through restricting access rights.

- Knowledge re-use (the competitiveness driver) requires sufficient compliance to standard formats and protocols, but also the minimum appropriate access restrictions to make the materials available as widely as possible.

- Collaboration supports the creation of new materials by bringing together different perspectives to allow new ways of looking at things, yet is also the vehicle for encouraging efficiencies from re-using existing distributed knowledge bases.

The most appropriate way of combining all three value drivers (the “3 Cs”) needs to be identified for each organization. This will be a dynamic requirement as business objectives change and develop in different parts of the organization, suggesting that any technology system and associated working practices will need to be flexible to accommodate changes in priorities.

Notes

1. For more information about working with maturity models and using them for peer learning, see Collison, C. and Parcell, G. (2004) Learning to Fly, 2nd edn, Chichester: Capstone Publishing Ltd.

2. Lawrence, P.R. and Lorsch, J.W. (1967) Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.