Chapter 12

MAKING MORE KNOWLEDGEABLE DECISIONS

Snapshot

Good decision-making matters in all organizations. Today there are even more pressures on decision-makers to reflect the priorities of many different people and institutions, so “good” decision-making can be even harder to achieve. Decision-making is a knowledge-intensive activity. Consequently, initiatives may be needed to help decision-makers to access and use the best available knowledge. An integrated approach has been developed that draws on essential knowledge-related practices that affect decision-making. It is organized around five broad factors: using experts, using technology, using internal and external collaboration, organizational learning about decision-making, and developing individuals as decision-makers.

Evaluating how well your organization performs against these five factors is a useful starting point. You can do this by working with the maturity model that describes five levels of performance for each factor. It provides a systematic framework for examining your current position and planning how to improve. If one part of the organization is better than another at one of the factors, then managing a peer learning process can help build the capability of the whole organization.

Helping individuals to become more effective decision-makers requires particular attention. The research also offers a framework of five useful personal competencies: linking the big picture with the detail required for action, defining boundaries, influencing others, maintaining momentum, and weighing up the balance of influences. Individuals can work on developing these in conjunction with coaches, mentors, and their own personal reflection.

Why this Matters

Good decision-making has always mattered. Today, people in organizations face even more pressures to make efficient and responsive decisions, whilst also complying with good governance and ethical approaches. Decision-making is a knowledge-intensive activity in which knowledge is, simultaneously, raw material, work-in-process, and deliverable. Many organizations, both private and public sector, are finding that they need to draw on a wider variety of knowledge to better serve the needs of increasingly demanding and sophisticated customers. Often access to knowledge comes through working within several interconnected networks of diverse individuals and organizations. Decision-making is often distributed across the organization to increase speed and flexibility, making it even more important for everyone to have a shared view of what the priorities are and what matters. It is a challenge for many organizations to ensure that decisions are based on the best available knowledge and do not work against one another. As decision-making is a very broad field, a useful definition to describe what we are looking at here is:

A “decision” is a commitment to a course of action that is intended to yield results that are satisfying for specified individuals.1

This definition emphasizes that decisions need to result in purposeful action with the value of that action being determined by relevant organizational stakeholders. Improving conversations about what matters, as well as learning from the results of action to improve future decisions, are particular areas where managers can contribute to better organizational decision-making.

What this Means for Your Organization

Good organizational decision-making is a capability that takes time and effort to develop. By understanding your organization’s current strengths and weaknesses in this area, you can identify opportunities for improvement.

We found that five factors need to be considered together in an integrated and holistic way. The main actions needed to become good at each factor are listed below.

Using Experts

- Recognizing decision-making situations which require expert input.

- The appropriate use of experts and expert panels to explore implications and provide advice.

- Ensuring the accessibility of experts to decision-makers.

- The development of experts in key areas which are particularly important to the organization.

- Ensuring that experts are proactive in passing on their knowledge to others.

- Learning from the contributions of external experts.

Using Technology

- Widespread and disciplined use of appropriate information systems, decision support tools, and collaborative working systems by decision-makers.

- Provision of real-time information for operational decision-making.

- Understanding of the principles of evidence-based decision-making such that facts and information are sought to help make sense of a situation and establish an evidence base appropriate to the type of decision.

- Providing access to external resources and databases.

- Using technology to involve those who need to contribute to the decision, no matter what their location.

- Managing information repositories with good governance.

Using Internal and External Collaboration

- Recognizing situations when a range of knowledge and points of view are needed for good decisions to be made.

- Using communities and networks to build understanding and capability in key knowledge areas.

- Involving external parties where appropriate to contribute knowledge and different perspectives, with clear codes of conduct being used regarding the protection of valuable knowledge.

- “Joining up” internal and external collaboration activities through the use of technology and through joint involvement in networks and communities.

- A consultative approach to decision-making being the norm.

Organizational Learning About Decision-Making

- Continuously appraising the ways decisions are being made, including whether experts, technology, and collaboration are being used appropriately and effectively.

- Understanding how to appraise risk in decisions and then reviewing the decision outcome to improve the appraisal process in the future.

- Sustaining an open culture in which debate and contributions to decisions are encouraged at appropriate points.

- Using a variety of processes to review and learn from decisions (including group and inter-group processes) and then being able to institutionalize changes when lessons have been learnt following a decision review. Also having a process to manage the future review of decisions to see if they need to be revised.

- Using people management processes (appraisal, reward etc.) that support consultative and team-based decision-making.

Developing Individuals as Decision-Makers

The most effective way in which individuals can become better decision-makers is either through personal reflection or guided reflection in a coaching context. Both should raise awareness of their personal style, preferences, and mental and emotional biases. The organization can support and encourage individuals to do this through:

- Embracing and modelling reflective practice at all levels, including making time and space for reflection in the design of agendas, meetings, and events.

- Encouraging people to share personal learning from reflection, for example through blogs (with constructive ground rules) or collective learning situations.

- Encouraging people to look outside their usual environment (internal or external) to find new ways of understanding issues.

- Instituting coaching and mentoring programmes to support the development of decision-makers.

- Making available training in how to support participative decision-making, for example facilitation, negotiation, conflict resolution, leadership etc.

- Offering training to senior decision-makers in techniques such as framing insightful questions, strategic influence, and managing change in complex systems.

A competency framework was developed through the research that can be useful for individuals (or coaches working with individuals) as they plan how to tackle a big decision, work out what to do differently when things don’t seem to be going to plan, or learn from experience once the decision has been implemented. This is outlined in Figure 12.1. The underpinning skills and abilities are summarized in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1: Developing decision-making competency

| Personal skills and abilities required | |

| Understanding and awareness | Awareness of how the organizational context affects the decision |

| Understanding of the organizational orientation to risk | |

| Ability to investigate the facts | |

| Reflective practice | Modelling open and transparent behaviour |

| Ability to challenge own thinking | |

| Ability to learn from experience | |

| Confidence to take risks and make mistakes | |

| Communication | Effective communication skills |

| Effective listening and questioning skills | |

| Ways of relating to other people | Recognizing the value of other people’s contributions |

| Knowing who to involve | |

| Maintaining external relationships | |

| Networking | |

| Trusting | |

| Managing emotions | |

| Awareness of time in relation to the effectiveness of decision-making | The timing of relevant external events |

| The time pressures surrounding the decision and the time pressures on others | |

| The impact of timeliness on the acceptance of the decision | |

| The impact of time on risk | |

| Making time and space to think and reflect during and after the decision | |

Figure 12.1: Knowledge-based competency framework for individual decision-makers

Creating an Action Plan

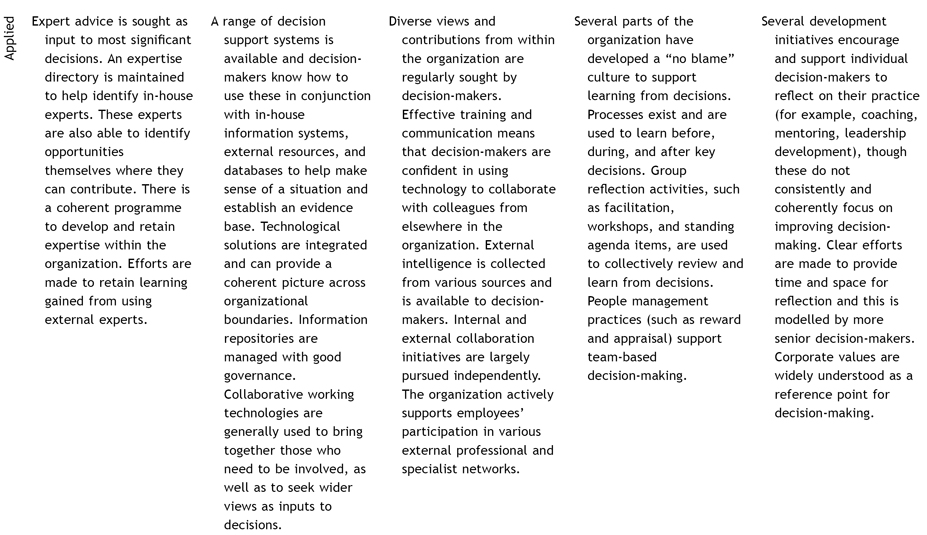

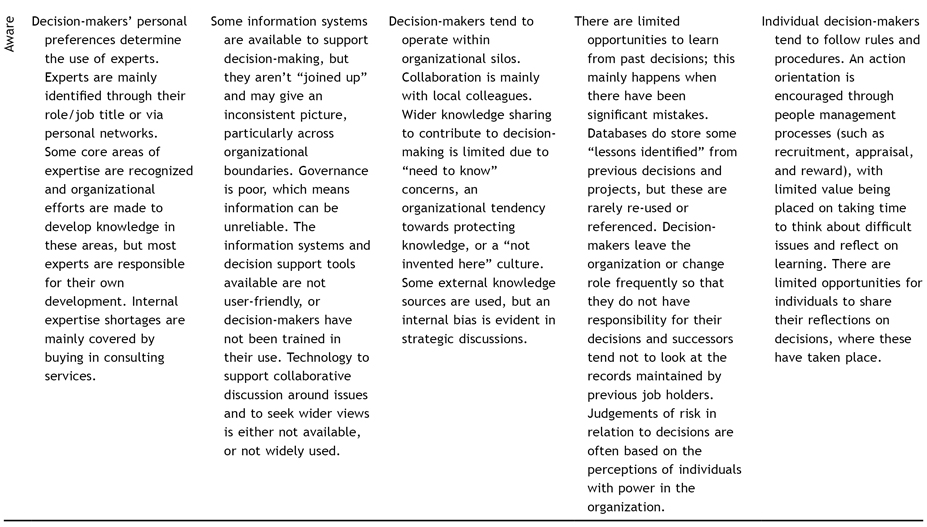

You can use a maturity model that covers the five factors that enhance organizational decision-making capability to assess the strengths and weaknesses of different parts of your organization. Then you can facilitate knowledge sharing between them. This peer learning process is a very effective way to build organizational capability. The maturity model is shown in Table 12.2.

Table 12.2: Knowledge enabled decision-making maturity model

The steps you could follow to use this maturity model are:

1. Identify a group of people representing different parts of your organization (different teams, activities or functions). At least six is desirable – 10–12 is probably the maximum. Invite them to a 1.5–2-hour workshop.

2. At the start of the workshop give everyone a copy of the model and talk through what the five factor headings mean so everyone has a similar understanding.

3. For each factor ask them each to rate their team/group/activity (as appropriate) according to the five level definitions.

4. Then ask people to identify where they would want to get to on each factor within the next 12 months (identify the gap between the current and desirable rating).

5. Ask them to pick the two priority areas that they expect to make the most difference if they succeeded in moving them from where they are to where they want to be within 12 months.

6. Collect the information and use a flipchart to represent who has what rating (the River Diagram shown in Figure 12.2 can be a useful way of depicting the results for all groups and factors). Add in the desired ratings and what the priorities for improvement are (maybe in a different colour).

Figure 12.2: River Diagram

7. Look at who is strong at each factor and who wants to improve on it. Connect these people so they can discuss what the strong group is doing and how the weaker group can learn from this. These “peer assist” conversations should ideally be started at the workshop, then encouragement given for them to continue afterwards.

More details about how to use an extended version of this approach are available in the book Learning to Fly.2 You may also choose to introduce a “company” or “KM programme” view at the end if you have other options to offer people who want to make improvements on particular factors.

Some hints and tips for getting the most from the peer learning process:

- Encourage people to start at the bottom (Aware level) and work up, rather than the top and work down, when they are deciding how to rate their part of the organization.

- You may decide that 12 months is too short a timeframe for improvements in your organization. More than three years is unlikely to be helpful though.

- There will be a lot of discussion about what the five factors mean for your organization. This is fine, as long as everyone understands and agrees with the final interpretation.

- The most value will be gained if you can repeat the assessment to track progress over time. This should be a productive learning process not an exercise in control and performance measurement. A learning approach encourages collaborative conversations and peer learning, bringing all parts of the organization up to their highest desirable levels.

- The discussion is the most useful part of this process – allow time for it and encourage it.

Real Life Stories

Different kinds of decisions need managers to apply the maturity model factors in different ways. In this section, we have stories from decision-makers about their approaches.

A Simple Decision that Needed a Strong Evidence Base: Using Technology and Collaboration to Collect and Check Facts

Simple decisions are not necessarily easy decisions, particularly when the issue is unpopular. This decision-maker needed to set priorities for the use of very limited shared resources. He worked with his team to carry out sufficient analysis of existing data to create an outline approach. He then explained the issue and the rationale for that approach to colleagues who would be affected, mainly in face-to-face meetings, following this up with the detail in emails with requests for answers to questions that would finalize the prioritization. The team created a “first cut” prioritization and put it out again for comments. This initial proposal was important because it allowed people to see the implications of the evidence that they had provided. Others saw how to improve their case for resource allocation. The final prioritization emerged from an iterative process in which everyone felt they had been given a fair hearing.

Using Personal Reflection and Collaboration with Others, Including Experts, to Make Sense of Complex Situations and Develop Options

When faced with a difficult aspect of a complex decision, this decision-maker said that he takes some time out. He would set aside a day, put everything out on a table, and apply some quality thinking to identify and understand the key concepts and establish a framework within which he needs to make the decision. By using this process in a recent complex decision he came up with two alternative models for a proposed way forward and shared them with a lot of people. These approaches evolved and didn’t survive in their original form, but they were a useful foundation for moving things forward. His view was that if you offer people something tangible, it is easier to get to them engaged and they can quickly say what they like or dislike. In general, for difficult decisions he believes it is helpful to engage people with a potential solution, then listen hard to what is said about it. Some of the concerns will be due to lack of understanding, which can then be addressed. Others will represent added value as they bring in alternative perspectives. This approach also helps generate a more defensible decision; the debate and refinement means that you also won’t be surprised by any questions at the end.

Using Personal Reflection, Engaging People Collaboratively, and Using Technology to Collect Evidence and Communicate Widely to Achieve Complex Organizational Change

This decision-maker considered how best to involve others in shaping the way forward in a complex decision about organizational change. He emphasized the need for a vision about what you want to get to, because it makes it easier to paint a clear enough picture about it for everyone to feel part of it. A decision-maker needs strong communication skills to be open, transparent, and clear with everyone. He commented that it never ceases to surprise him how much communication is actually needed. This decision-maker’s organization tends to be very consultative and that can mean that the discussion continues until everyone agrees, which actually never happens. He said that in reality you need to find a balance between consultation and decision-making. The best approach is to identify where buy-in is needed. Project management tools can be used to provide opportunities for consultation and set the context for this. He commented that you need to know the difference between productive consultation and just creating opportunities for people to let off steam. This means being really clear about why you need consultation and what the outcome needs to be, and being ruthlessly honest about where people can contribute constructively. He added that honesty is important – there is a tendency to over-promise in terms of consultation but it is important that people feel they can contribute. People appreciate clarity about where and when the decision is being made. This means showing that there is a rational approach and evidence is being weighed.

Organizational Learning About Decision-Making

This decision-maker commented that although his organization has a systematic process to evaluate decisions after the event, question the process, and identify lessons learnt, the lessons are largely carried with the people involved who share their stories and anecdotes. In general, he does not value knowledge repositories because all too often they don’t get used. Where a review provides an institutional lesson that needs to be learnt, then it is important to change structures and policy so that the change becomes embedded in standard systems. Beyond this, in his view internal knowledge transfer happens best between individual people.

Top Tips

One of the main benefits of using a maturity model approach for capability development is that it can stimulate higher quality conversations about issues that otherwise can be difficult to articulate. The framework creates a common language around the topic of organizational decision-making as well as a basis for objective assessment. Therefore, it is essential to make time for these conversations and to get a wide variety of people involved.

Other things to bear in mind in developing a knowledge-based approach to decision-making are:

- Our own biases: We use heuristics (rules of thumb) to speed up our decision-making all the time. However, these can create risks of bias if we use them inappropriately. Typical biases include preferring alternatives that keep things as they are and making choices that justify past decisions. All the recommendations to manage biases involve improving access to knowledge or increasing individual or organizational reflection. Encouraging people to use the competency framework will be helpful – encourage HR colleagues to consider incorporating it in the organization’s competency framework.

- Being aware of the types of decisions that we are making: The consequences of a decision outcome may not always be clear ahead of time. It may not even be possible to make a full link between cause and effect in particularly complex situations. We need to develop an awareness of different types of decision and learn to draw on knowledge in different ways for each. A useful way of categorizing different types of decisions has been described by Dave Snowden and Mary Boone3 and is summarized in Table 12.3. Practice using this to assess what kind of decision-making situation you are dealing with.

Table 12.3: Categorizing decision types

| Type of decision | Characteristic | Decision-making approach needed |

| Simple | Clear cause and effect relationships are evident to all and right answers exist. | Reduce individual biases through a fact-based approach, good use of evidence, application of best practices and clear processes, and clear direct communication. |

| Complicated | Cause and effect relationships can be discovered, though they are not immediately apparent. Expert diagnosis is required and more than one right answer is possible. | Use high quality evidence with individual experts and expert panels to interpret it, challenging standard thinking through bringing in outside perspectives and encouraging creative thinking. |

| Complex | There are no right answers, but emergent and instructive patterns can be seen in retrospect. Efforts need to be made to probe the situation and sense what is happening to find the patterns of relationships. | Increase collaboration and communication to encourage discussion and surface issues and ideas, creating the conditions where patterns can emerge over time. |

| Chaotic | The relationships between cause and effect are impossible to determine because they shift constantly and no manageable patterns exist. Acting to establish order is needed through directive leadership. | Take action to find out what works through clear direct leadership, rather than seeking right answers. The aim is to move the decision situation away from chaotic to one of the above contexts (usually complex). |

The Research and the Team Involved

This project was carried out by a working group of knowledge managers from member organizations of the Henley KM Forum during 2009. Expert advisers and academics also participated. Nineteen telephone interviews with decision-makers in ten KM Forum member organizations (half public sector and half private sector) were used to collect the data and an extensive review of the academic and practitioner literature was also carried out.

The intention was to help knowledge managers engage in productive dialogues with colleagues in various functions about how Knowledge Management could build decision-making capability in the organization. It was not intended to provide prescriptive advice for a particular business.

The Project was co-championed by Professor Jane McKenzie of Henley Business School and Sindy Grewal of The Audit Commission. The researcher was Dr Christine van Winkelen of Henley Business School. Working group members included representatives from:

The Audit Commission

Balfour Beatty

The British Council

Cranfield University

DCSF

Ministry of Defence

Other member organizations of the KM Forum also identified interviewees to participate in the research:

Foreign and Commonwealth Office

HMRC

Mills and Reeve

MWH

National College

Permira

Syngenta

together with invited associates: Alex Goodall (previously Unisys) and Tim Andrews (Stretch Learning)

Final Reflections from the Research

It may be helpful for managers to view developing organizational decision-making capability as a series of intellectual capital investments. The five factors that make up the maturity model can be mapped onto the core components of intellectual capital as shown in Table 12.4.

Table 12.4: Building decision-making capability as a series of intellectual capital investments

| Intellectual Capital Component | IC investment area (maturity model factor) | Most significant contributions to decision-making |

| Human Capital | Identifying experts and developing expertise. | Sensemaking and identifying options. |

| Supporting reflective practice. | Managing individual decision-maker bias, increasing range and depth of experience, increasing debate, challenge and openness. Developing expertise. Reflection on practice and self-awareness to develop strategic decision-making skills. | |

| Structural Capital | Using technology to structure, integrate, and provide access to explicit knowledge resources. | Access to current and well structured explicit knowledge to provide input for decision-making. Support experts in their decision-making. |

| Decision review process. | Recognizing different kinds of decision-making situations. Developing an appropriate repertoire of decision-making approaches. | |

| Relational Capital | Adopting an integrated approach to internal and external collaboration. | Gathering intelligence. Accessing multiple perspectives to formulate the scope of the decision to be made in more complex situations. Making connections to create knowledge to generate new options. |

Notes

1. See p. 422 in Yates, J.F. and Tschirhart, M.D. (2006) “Decision-making expertise”, in Ericsson, K.A. et al. (eds), The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance, New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 421–438.

2. For more information about working with maturity models and using them for peer learning, see Collison, C. and Parcell, G. (2004) Learning to Fly (2nd edn), Chichester: Capstone Publishing Ltd.

3. Snowden, D. J. and Boone, M.E. (2007) A leader’s framework for decision making, Harvard Business Review, 85(11), 69–76.