Chapter 15

DEVELOPING KNOWLEDGE-SHARING BEHAVIOURS AND EFFECTIVE KNOWLEDGE ACTIVISTS

Snapshot

A deep understanding of what “knowledge-sharing behaviour” really involves allows managers to select people for important roles and to design initiatives to encourage positive behaviours. The Henley Knowledge Sharing Behaviours model has been translated into a competency framework that provides a useful reference point for many development initiatives. Awareness of the elements of the model can support processes such as performance management and leadership development within the organization, ideally through integration into existing competency frameworks. When individuals are aware of these competencies, it can also help them focus self-development activities. Understanding the link to personality is also useful because in general it is easier for people to change their behaviour in a way that is in tune with their preferred style. It is also important to recognize that behaviours that may “come naturally” to some people may be difficult for others to sustain.

In addition to encouraging widespread knowledge-sharing behaviours, in most organizations the team dedicated to planning and implementing knowledge-related initiatives is very small. Those responsible for improving the use of knowledge in the organization need to engage allies and encourage local knowledge activists. There are nine characteristics of an effective knowledge activist, which are essentially a refined application of the broader knowledge-sharing behaviours competency model. The characteristics have been used to prepare a framework to help managers understand what to look for in their knowledge activists and how to develop these people.

Why this Matters

Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours Affect Business Capability

From collaborative product development through to factory floor process improvement, the ability to share knowledge effectively – with supply chain partners and customers, or among employees – is of critical importance. Increasingly, it is businesses’ ability to unlock the information held in people’s heads that makes the difference between success and failure, with failure, in some cases, impacting on corporate survival itself. But even as growing numbers of managers within organizations come to understand this, they face an awkward dilemma: knowing that knowledge sharing is important is one thing, and knowing how best to actually share that knowledge quite another.

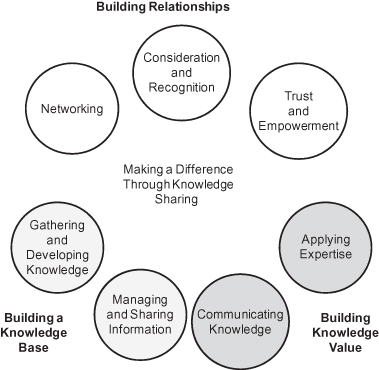

The bottom line is that by understanding what influences knowledge-sharing behaviour, managers can improve the way knowledge is shared within their business. The three fundamentals of effective knowledge-sharing behaviour are: Building Relationships, Building a Knowledge Base, and Building Knowledge Value. These are underpinned by seven knowledge-sharing “competencies”: personal behavioural characteristics that impact on how well (or not) knowledge is shared. Understanding, recognizing, and developing these competencies is vital for improving the way that knowledge sharing takes place within organizations.

Knowledge Activists Encourage Knowledge Sharing

“Knowledge activism should be a characteristic of all good managers. Stressing the need to be active, rather than simply using the label ‘activist’ helps to achieve this.”

Chris Collison, Director, Knowledgeable Ltd

Knowledge Management is not something that can be “done” to an organization by a knowledge manager – all managers and employees have a role to play in managing the organization’s knowledge effectively. Knowledge sharing is a key aspect of that role. Most organizations only have a very small team or even a single manager dedicated to thinking about knowledge issues. Other people in the organization must be engaged as allies and local knowledge activists in order to get things done.

In any business where a focus on knowledge can contribute to improved effectiveness, you’ll find people playing the role of “knowledge activists”. They are people who see the value of knowledge to the organization and who support the implementation of knowledge-related initiatives. As such, they play a vital role: encouraging knowledge activities, participating in projects to create and share new knowledge, and connecting seekers of knowledge with reliable sources. This raises the question: “what characteristics and skills make knowledge activists effective?”

What this Means for Your Organization

Competencies Underlying Knowledge-Sharing Behaviour

“In building a knowledge base, less is often more: I see a lot of effort wasted in archiving information – often of poor quality – that will never be used.”

Robert Taylor, Business Excellence Director, Unisys

The Henley Knowledge Sharing Behaviours model has three key components: Building Relationships, Building a Knowledge Base, and Building Knowledge Value. The logic is that first, better relationships contribute towards greater sharing; second, the more in-depth and detailed a body of knowledge is, the more likely it is to be of business value; third, that its value will be enhanced by more effectively organizing its capture, storage, and sharing. Each component has more than one competency. Figure 15.1 shows how the competencies link to the components.

Figure 15.1: Knowledge-Sharing Behaviour competency framework

Characteristics and Skills of Effective Knowledge Activists

Knowledge activists are allies who promote the implementation of knowledge-related initiatives. They have some local responsibility for knowledge activities, but may have other responsibilities as well. They engage in relationships, participate in projects, and create new knowledge. They also connect seekers with sources of knowledge and develop these relationships. Some knowledge activists are experts in a particular field, others have a broader understanding of the business. The three broad categories of effective knowledge-sharing behaviour (Building Relationships, Building a Knowledge Base, and Building Knowledge Value) describe their characteristics and skills, however they are manifested in particular ways. These aren’t inconsistent with the knowledge-sharing competency framework, just a specific interpretation for these key individuals.

There are nine typical characteristics and skills of effective knowledge activists. Some of the characteristics and skills are more pervasive than others. Each is therefore described as strong or moderate in Table 15.1.

Table 15.1: Applying the Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours framework to knowledge activists

| Characteristics and skills of knowledge activists | ||

| Building Relationships |

|

Developing relationships |

|

|

Internal belief | |

|

|

Cultural alignment with organization | |

| Building a Knowledge Base |

|

Action-oriented |

|

|

Project management | |

|

|

Information brokering | |

|

|

Creativity | |

| Building Knowledge Value |

|

Dialogue and communication |

|

|

Credibility through experience |

![]() = Strong,

= Strong,

![]() = Moderate.

= Moderate.

In addition to these characteristics and “soft” skills of activists, there is also a whole raft of harder, “technical” skills that these people might need: content architecture, database management, IT application skills and so on – depending on your organization’s knowledge strategy.

Creating an Action Plan

Using the Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours Competency Framework

“Building high-quality relationships is critical, because it’s through relationships that knowledge flows, and value is created.”

Debbie Lawley, Director, Willow Transformations (formerly at Orange)

The development of the Henley Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours model into a detailed competency framework is provided in Tables 15.2–15.8. These include what each of the seven components involves, how certain personality traits may influence it, and what someone can do to develop it. You can integrate this into your own organization’s competency framework, or use it as a standalone element within other initiatives that would benefit from better knowledge sharing.

Table 15.2: Building relationships – networking

| What the competency is | What it is not | The influence of personality |

| Seeking contacts and building relationships with

others. Knowing who has specific skills, experience, and knowledge and how to contact them. Involving people with relevant expertise in projects and activities. |

Wasting time “re-inventing the

wheel” by not involving the right people. Focusing solely on your own area of the business and treating your own department as an island to be defended. Limiting the knowledge base that you draw on to make decisions. Working separately from others and/or competing with them. |

People who are ambitious and concerned about things going well and about how others see them, place more importance on networking as a matter of course. Those who set themselves less ambitious work targets or don’t worry about the views of others may need to pay more attention to developing this competency. |

| Developing the

competency Identify key people and key teams across the business who you need to cooperate with. Arrange meetings and discuss how you can work together more effectively. Maintain a list of people who can provide you with assistance. Record their areas of expertise and contact details. Alternatively, use your organization’s skills database if it exists – and keep your own record updated in the system. Participate in appropriate forums and professional bodies. Contact people in your network regularly to foster mutually beneficial relationships. Don’t just contact them when you need something. |

||

Table 15.3: Building relationships – consideration and recognition

| What the competency is | What it is not | The influence of personality |

| Listening attentively to the contributions of

others. Reacting to others with consideration and tolerance. Building rapport and motivating others through recognition, encouragement, and reward. |

Forcing your own opinions onto other

people. Ignoring input from others. Making assumptions about what others are thinking. Claiming the glory for yourself and not acknowledging the wider contribution. |

People who are keen to achieve high standards, are outgoing and comfortable in social situations, and are keen to present a positive image of themselves may find it easier to build rapport with others and recognize the contribution that other people can make. A pragmatic and common sense approach to life can also make it more likely that someone will be tolerant and considerate to others. In contrast, people who set less ambitious targets, are reserved, self-critical, and/or have a particularly conceptual view of the world, may need to pay more attention to developing this competency. |

| Developing this

competency When a colleague is communicating an idea, listen and ensure that you understand what he or she has said before you respond. Check understanding by asking questions or by reflecting back what has been said by paraphrasing the key points of what you have heard. Try to understand another’s point of view based on who they are, the likely pressures they are under, and their goals. Be objective and non-judgemental when interacting with others. Confront the issues, not the person. Use people’s names when you speak to them. |

||

Table 15.4: Building relationships – trust and empowerment

| What the competency is | What it is not | The influence of personality |

| Providing others with the knowledge, tools, and other

resources to complete a task successfully. Considering knowledge as a resource to be used for the “common good”. Openly sharing knowledge that others may find useful or relevant. Treating others in a fair and consistent manner. |

Preventing others from making significant

contributions. Keeping key pieces of information to oneself. Using information as power. Ignoring opportunities to coach or provide feedback to others. |

People who are keen to meet high standards, are confident with others and are supportive and tolerant of the needs of others are more likely to act fairly and give people the authority and resources they need to succeed. In contrast, those who set less ambitious targets, don’t necessarily worry about how things will turn out, and prefer their own company may be less interested in the needs of others and may need to focus on developing this competency. |

| Developing this

competency Actively seek to receive feedback about your behaviour with regard to knowledge sharing. Improve the level of genuine and honest feedback you provide to others. Find ways to coach others in real time. Offer to act as a coach for a particularly stressful event by giving the opportunity to rehearse before and debrief afterwards. Identify tasks that would be challenging to others and delegate to them where appropriate. Set the terms of reference for work and not the detailed plan. |

||

Table 15.5: Building a knowledge base – gathering and developing knowledge

| What the competency is | What it is not | The influence of personality |

| Continual regard to personal and professional

development. Working to build on previous experience. Seeking out ideas and opinions from other people. Aiming to keep your own knowledge up-to-date. |

Failing to take advantage of knowledge and skills

across your organization. Ignoring coaching or feedback opportunities. Disregarding own development needs. Alienating yourself from others at work. |

People who are ambitious, keen to achieve high standards, and are outgoing and interested in other people may find it easier to develop and keep their knowledge up-to-date. In contrast, people who set themselves lower targets and are relatively less comfortable with and interested in other people, may need to focus on developing this competency. |

| Developing this

competency Always be willing to learn. Encourage your colleagues to express ideas to you openly. Find a mentor with whom you can regularly review progress and who will provide constructive feedback and give coaching where necessary. Find every opportunity to discuss your work with others (other teams, senior managers, etc.) and to find out about their projects. Organize lunch meetings where individuals can share best practice on key work issues. Visit leading edge firms and transfer ideas back to your team. |

||

Table 15.6: Building a knowledge base – managing and sharing information

| What the competency is | What it is not | The influence of personality |

| Creating and supporting systems and procedures that

individuals can use to file, catalogue, and share knowledge. Making effective use of available media to share knowledge across the organization. Encouraging others to use knowledge-sharing systems. Encouraging communication and collaboration. |

Waiting to be asked for information rather than

offering it to others. Adopting a silo mentality within teams and departments. Taking a back seat in discussions rather than offering relevant knowledge or the benefit of your experience. Failing to keep everyone up-to-date with progress. |

People who are ambitious and keen to meet high standards may tend to use and encourage others to use Knowledge Management and Information Management systems in the organization. In contrast, people who are less ambitious and set lower targets and/or place their priorities outside of work may need to pay more attention to developing this competency. |

| Developing the

competency Remember that sharing your information might save someone “re-inventing the wheel”. Ensure that you have access to, and are able to use the systems available for sharing knowledge in the organization. When receiving new information, ask who else would be interested or who needs it. Volunteer knowledge, views, and opinions before being asked. Share what you have learnt from your experiences – successes and failures. Participate actively in communities relating to your work practices. |

||

Table 15.7: Building knowledge value – communicating knowledge

| What the competency is | What it is not | The influence of personality |

| Explaining and expressing ideas, concepts, and opinions

in a clear and fluent manner both in writing and via

presentations. Adapting your presentation style according to the communication channel/audience. Being aware of the needs of the audience. |

Providing knowledge that recipients do not

need. Not allowing the opportunity for people to check that they have understood your message. Failing to adapt your approach to the audience. Communicating the “nice to know” rather than the “need to know”. |

People who find that they enjoy explaining their ideas to others may be particularly creative and enjoy thinking about new ideas in general. If they are also relatively outgoing, even though they may be tense before important events, then they are likely to find it easier to adapt the style of a presentation or document to the needs of the audience. In contrast, people who are particularly pragmatic, tend to be nonchalant, and/or are reserved with strangers, may need to pay attention to developing this competency. |

| Developing the

competency Research the needs and points of view of those attending your presentations and reading your documents. Be clear about the purpose of the communication. Ask others to give a summary of what you have said to check how well you have communicated. Ask a colleague to evaluate your work critically and give you some tips on areas of improvement. Make an effort to mix with a variety of people, inside and outside your organization, and try consciously to identify the different styles that they adopt. Practice adapting your style to fit with theirs. |

||

Table 15.8: Building knowledge value – applying expertise

| What the competency is | What it is not | The influence of personality |

| Understanding the technical aspects of your

job. Ensuring that you apply your knowledge and previous experience effectively. Making the most of available technologies to ensure that work is completed effectively and efficiently. |

“Re-inventing the wheel” by failing

to look at the work others have already carried out. Withholding information that you know will be useful to others. Failing to take action that you know is appropriate. |

People who are intellectually curious and keen to meet high standards (including worrying about how things will turn out) are likely to pay particular attention to applying technical expertise and job knowledge. In contrast, those who adopt a more down to earth approach, place their priorities outside of work and are easy-going and even nonchalant, may need to work harder to develop this competency. |

| Developing the

competency Review your current level of knowledge in your job and identify any key gaps. Seek out training and development opportunities to fill each of the identified gaps. Seek opportunities for involvement in a technically challenging project where you will have to update your skills and knowledge. Identify areas of future technical or commercial knowledge or skill that are likely to become critical to success in your job and focus on developing these. Organize discussions at work with other specialists in your field. Meet regularly to review and discuss relevant and topical issues. Participate in relevant communities of practice and professional associations. |

||

Selecting for the Characteristics and Skills of Knowledge Activists

To help you identify knowledge activists who can help drive change initiatives, use Table 15.9 to decide what to look out for, or what to design into recruitment criteria.

Table 15.9: Identifying knowledge activists

Real Life Stories

Using the Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours Competency Framework

In this section, two organizations explain how they intended to use the framework1 following a survey of knowledge-sharing behaviour competency levels (including the perceived value of that competency) across several teams.

Mobile Phone Operator

Employees of this Mobile Phone Operator scored higher than the average in the competency areas of Communicating knowledge and Applying expertise. The internal culture had tended to foster and respect clear communication. This was very much in line with the company’s brand approach which aimed to clearly and simply convey products and service offerings to customers. It spilled over into the way the company worked internally, emphasizing the use of simple, friendly language that makes the point. Being practical, having valuable competence in applying and achieving results has been very important to them.

Increasingly, Managing and sharing information had become more important in the organization. This was expressed in the comparatively higher than average rating given to the importance of this competency. As a large company with operations in many different countries, understanding what is known within the organization had becoming a strategic issue. Many senior level messages highlighted the need to share and learn from each other.

The Mobile Phone Operator intended to use the competency framework in three ways:

Organizational competency development: The internal culture programme includes leadership development. The focus would be on understanding the important implications of this work for self-development in leaders.

Aid to selecting facilitators and community leaders: The full set of personality traits that have been linked to knowledge-sharing behaviours include imagination, achieving, and gregariousness. Understanding these relationships is very helpful for those who have the responsibility for selecting knowledge leaders in the company.

Trouble shooting in collaborative situations: The set of seven knowledge-sharing behaviours, together with the definitions of what competency means and does not mean, would be used within communities and other collaborative contexts when it was felt that improvement is needed. It would act as a coaching aid, helping groups to understand what good knowledge sharing looks like and to pinpoint areas for development.

Thames Water

Thames Water is part of one of the world’s largest water enterprises operating actively around the globe. The KM Programme had been running for two years at the time this survey was completed and had developed a Balanced Scorecard approach to monitoring and measuring progress in key areas, linked to the KM Strategy goals based around four strategic building blocks:

- Making Knowledge Visible

- Building Knowledge Intensity

- Developing Knowledge Culture

- Building Knowledge Infrastructure

“It’s important to recognize that knowledge matters: until you do that, you haven’t left the starting block. Some organizations recognize this – but many don’t.”

Peter Hemmings, Principal Consultant, KN Associates (formerly at Thames Water)

The respondents to the Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours and Personality survey were from all areas and levels within the organization. Most had some involvement with Knowledge Management, including community participation. The pattern of results reflected the emphasis that the organization placed on networking and applying expertise: performance against both these competencies was rated comparatively highly.

The importance of knowledge sharing and behavioural attributes was recognized. The company sought to embed them across the organization through the performance development process based on the Thames Water Competency Dictionary. Future plans included using key attributes from the Competency Dictionary as part of the organization’s recruitment process and building them into leadership development across the business. These areas linked directly with “Developing a Knowledge Culture”, one of the four building blocks of the Knowledge Management Strategy.

Top Tips

![]() Integrate the Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours competency framework into

your own competency system. This embeds knowledge sharing into people management

practices.

Integrate the Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours competency framework into

your own competency system. This embeds knowledge sharing into people management

practices.

![]() Tailor development of Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours to personal areas of

strength by taking into account personality and style preferences. Try to avoid

a “one size fits all” approach.

Tailor development of Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours to personal areas of

strength by taking into account personality and style preferences. Try to avoid

a “one size fits all” approach.

![]() Use the Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours model to audit communities of

practice, virtual teams, and other groups where effective knowledge sharing is

essential for performance.

Use the Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours model to audit communities of

practice, virtual teams, and other groups where effective knowledge sharing is

essential for performance.

![]() When looking for knowledge activists, it is useful to focus on

knowledge-sharing behaviours. Technical skills can be easier to develop than

underlying behaviours.

When looking for knowledge activists, it is useful to focus on

knowledge-sharing behaviours. Technical skills can be easier to develop than

underlying behaviours.

![]() Effective knowledge activists are far more likely to come from inside

the organization than outside.

Effective knowledge activists are far more likely to come from inside

the organization than outside.

![]() Knowledge managers and activists learn a lot from external networking.

This gives them access to other people in similar roles at different stages of

development.

Knowledge managers and activists learn a lot from external networking.

This gives them access to other people in similar roles at different stages of

development.

The Research and the Teams Involved

The research that produced the Henley Knowledge-Sharing Behaviours model, its associated competency framework, and investigated the links to personality was conducted between 2002 and 2003. A literature review was carried out to explore the research that had previously been done in the area of both personality and knowledge sharing. The study of personality in relation to work behaviours and performance in the workplace is a well-established area, which offered the opportunity to use an existing tool for measuring personality traits. The personality attributes were from the SHL IMAGES™ questionnaire, which provided a broad high-level view of personality, consistent with what is known as the “five factor model”. As there was no existing tool to measure knowledge-sharing behaviours, focus groups, supported by the literature review, were used to create a model and inventory using competency components and item content from the SHL Competency Framework. A preliminary round of data collection was used to derive a short form of the inventory with 42 items (six items per scale). This Inventory and the IMAGES™ questionnaire were emailed to participants who were asked to complete both, and also to rate the importance of each of the seven competencies for their own jobs. Where possible, questionnaires were emailed to peers, who were asked to rate the participants on the seven competencies. The total sample consisted of 241 participants from 28 organizations. Peer ratings were received for 54 people. Factor analysis of the data provided support for the Knowledge-Sharing Behaviour competency model and suggested that the seven competencies are distinct and stable. Correlations were used to examine the relationship between the six personality scales and the competency scales.

The research was co-championed by Anna Truch of Henley Business School and Dr David Bartram of SHL Ltd. Dr Christine van Winkelen of Henley Business School provided project support. Companies involved in the working group included:

DTI

EC Harris

Ericsson

EZI

Getronics

Orange

QinetiQ

Thames Water

Unisys

Professor Malcolm Higgs and Dr Judy Payne, both of Henley Business School, also supported this research.

The research into the characteristics of knowledge activists was carried out during 2004 and 2005. Following a review of the literature to generate an expected profile of characteristics and skills, the extent to which they were reflected in practice was explored through interviews with knowledge managers, knowledge activists, and the customers of KM initiatives in three companies. The Project was co-championed by Dr Judy Payne of Henley Business School and Debbie Lawley of Orange. Keith Farquharson of EDF Energy provided research support. Companies involved in the working group included:

Aegis

AWE

Buckman Laboratories

Defence Procurement Agency

DLO Andover

GSK

Highways Agency

Metronet Rail

Nissan

Orange

QinetiQ

Unisys

Both phases of the research were intended to provide insights into knowledge-sharing behaviours that could support practical initiatives in organizations. They were not intended to provide prescriptive advice for any particular organization.

Final Reflections from the Research

It is important to realize that there is no “good” or “bad” personality profile, it is just that we each have different preferences. By being aware that there are differences, managers can tailor development initiatives so that people can play to their strengths, as well as learning ways of coping in situations that don’t come so naturally to them. Our personalities remain relatively static as adults (there can be some changes, but for many people these are relatively minor). As knowledge sharing becomes increasingly important in distributed, virtual, ever-changing organizational teams, giving people some clarity around what is expected, what effective behaviour looks like and what support is available for development in line with their personal style is the basis for improved performance.

Note

1. The cases were prepared in 2003. Reproduced by permission.