14 Professional photography

This chapter reviews photography as an occupation, starting with a discussion on how images are read. It looks broadly at the qualities you need for success in widely differing fields, and discusses markets for many kinds of professional photography, from art photography to scientific photography. Most of the types of photography outlined here are discussed further in greater organizational and technical detail in Chapter 12.

How photographs are read

If you are really going to progress as any kind of photographer, in addition to technical expertise you need a strong visual sense (something you develop as an individual). This should go beyond composition and picture structuring to include some understanding of

why people see and react to photographs in different ways. The latter can be a lifetime’s study, because so many changing influences are at work. Some aspects of reading meaning from photographs are blindingly obvious, others much more subtle. However, realizing how people tend to react to pictures helps you to predict the influences of your own work – and then to plan and shoot with this in mind.

The actual physical act of seeing first involves the lens of your eye forming a crude image on the retina. Second, it concerns your brain’s perception and interpretation of this image. You might view exactly the same scene as the next person but differ greatly in what you make of what you see. In the same way, two people may look at the same photographic print but read its contents quite differently.

Look at Figure 14.1, for example. Some people might see this picture primarily as a political document, evidence of life under a particular regime. For others, it is a statement documenting the subjugation of women. Some would find it insulting on ethnic grounds, or alternatively see it as a warm picture of relationships. Still others may simply consider the shot for its composition – the visual structures it contains. Again, the same picture could be read as containing historical information on dress or decor of a particular period, or it might even be seen as demonstrating the effect of a particular camera, film or lighting technique.

None of us is wholly objective in interpreting photographs – everyone is influenced by their own background. Experience so far of life (and pictures) may make you approach every photograph as a work of art, or some form of political statement, or a factual record for measurement and research, etc. This kind of tunnel vision, or just general lack of experience, confuses visual communication between photographer and viewer. In a similar way, it is difficult to imagine a colour you have not actually seen or to speak words you have never heard.

Figure 14.1 This picture was taken by Bert Hardy in 1949, for the weekly magazine Picture Post (see text).

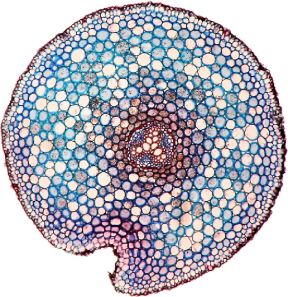

Figure 14.2, for example, is an image of a cross-section of the root of a buttercup plant taken through a microscope. A viewer who is interested in creative photography and is not familiar with seeing photomicrographs would observe an abstract pattern and would be interested in the composition of the image and the aesthetic result. A scientist working in the field of horticulture would be interested in observing the structure of the vascular tissue in the centre for transporting water and the individual cells captured. The point is that none of us works entirely in a vacuum. Unless you are uncompromisingly working to please yourself you must think to whom your photography is directed and how is it likely to be received. This will help to clarify your aims in approaching subject and presentation.

Figure 14.2 Photomicrograph of a cross-section of the root of a buttercup plant (Ranunculus repens).

Sometimes your visual communication must be simple, direct and clear – as in most product advertising. This may be aimed at known groups of receivers identified because they are readers of a particular journal, drivers past billboards or people buying at art store counters. Other photographs may be more successful and mind-provoking when they suggest rather than state things. The more obscure your image, the more likely it is to be interpreted in different ways – but maybe this is your intention?

Much also depends on the way your pictures are physically presented – how they relate to any adjacent pictures, whether they appear on pages you turn or are isolated in frames hung on the wall. Some photographers add slogans, quotations or factual or literary captions when presenting their work to clarify it, to give an extra ‘edge’ by posing questions, or even purposely to confuse the pictures. They often rate word and image as equally important. It is an approach that has worked well in the past (see examples by Duane Michals, Jim Goldberg and Barbra Kruger). In less able hands literary additions can become a gimmick or a sign of weakness, patching up an inability to express yourself through pictures. They can easily seem pretentious (fowery titles) or patronizing (rhetoric emphasizing something viewers are well able to appreciate for themselves). It is significant that in the advertising world copywriting is a very skilled profession, heavily market-researched. Pictures and words are planned together, adding a great deal to total message impact.

Being a professional photographer

Working as a professional photographer means that, in addition to visual and technical expertise, you will have to be reliable and have good fnancial and organizational skills. People rely on you as a professional to produce some sort of result, always. Failure does not simply mean you receive no fee – most work is commissioned, so you have let someone down. A client’s money invested in models, props, special locations, etc. is thrown away, a publication deadline may be missed or an unrepeatable event remains undocumented.

You therefore have to ensure – as far as humanly possible – that everything in the chain between arriving to shoot and presenting the finished work functions without fail. You need to be an effective organizer of people, locations, transport, etc., able to make the right choice of time and day, and, of course, arrive punctually yourself. You must be able to anticipate holdups and avoid them. As a last resort, you should know how to act if a job has to be abandoned or re-shot. Pressures of this kind are both a worry and a stimulus – but, of course, they make a successful result all the more worthwhile.

As a professional photographer you also have to produce results at an economical speed and cost. You must think of overheads such as rent and taxes, and equipment depreciation, as well as direct costs such as photographic materials and fuel. It is seldom possible to linger longingly over a job as if it was a leisure occupation. You also need to know how to charge – how to cost out a commission accurately and balance a reasonable proft margin against client goodwill (will they come again?), bearing in mind the competition and the current going rate for the job. For more details on estimating the costs and deciding how to charge, see Chapter 15.

Equipment is no more or less than a set of tools from which you select the right ‘spanner’ for the picture you have in mind. Every item must give the highest quality results but also be rugged and reliable – vital gear may need duplicate back-up. The cost of fouling up an assignment because of equipment failure can be greater than the photographic equipment itself, so it is a false economy to work with second-rate tools. You must know too when to invest in new technology, such as digital gear, and what is best to buy.

One of the challenges of professional work is to make interesting, imaginative photographs within the limitations of a dull commercial brief. For example, how do you make a strong picture out of a set of ordinary plastic bowls – to fill an awkward-shaped space on a catalogue page? Eventually, you should be able to refuse the more dead-end work, but at first you will need every commission you can find. In the same way, you must learn how to promote yourself and build up a range of clients who provide you with the right subject opportunities and freedom to demonstrate your ways of seeing, as well as income. Another relatively open way of working is to fireelance as a supplier of pictures for stock libraries.

Photography is still one of the few occupations in which you can create and make things as a one-person business or department. It suits the individualist – one reason why the great majority of professional photographers are self-employed. There is great personal satisfaction in a job which demands daily use of visual and technical skills.

Turning professional

There is no strictly formal way into professional photography. You do not have to be registered or certifed, or, for most work, belong to a union. Most young photographers go through an art college or technical college photography course. Some come into photography from design, fine art or some form of science course. Others go straight into a professional business as a junior member of staff and work their way up, perhaps with part-time study.

In the UK, Further Education (FE) colleges and university photographic programmes include Higher National Certifcate (HNC), Higher National Diploma (HND) and Foundation Degrees (FdA). Other programmes include Bachelors (BA) and Masters (MA) degrees. Certifcate courses tend to train you for the technical procedures and processes that make you immediately useful today as an employee. Diploma courses are also craft-based but are more broadly professional. Foundation Degrees in photography include a considerable work-based learning component, as well as involving modules in the practice and historical and critical aspects of photography. Foundation Degrees are two-year courses, but students may elect to progress to the final year of a BA course. Most degree courses aim to help develop you as an individual – they are academic, like humanities courses, encouraging original ideas and approaches which pave the way to tomorrow’s photography and to wider roles in the creative industries, roles in image management, galleries, museums and academia, as well as into traditional jobs. The best courses develop photographic skills and critical thought as well as develop you as an individual. Ideally, you should seek work experience and work placements during the course to make contacts in the world of photography in which you wish to work. Alongside this, your best proof of ability is a portfolio of outstanding work. Organizations, such as the Royal Photographic Society in the UK and various professional photographers’ associations, offer fellowships to individuals submitting pictures considered to reach a suitable standard of excellence. Make sure that your commercial portfolio contains not only photographs but also cuttings showing how your photography has been used in print. Pages from magazines, brochures, etc. (‘tearsheets’) all help to promote confdence in you in the eyes of potential clients.

In the United States, many students take their first course in photography while in high school, between the ages of 14 and 17 years. Once graduated from high school, there are a number of paths to studying photography, depending upon the person’s interests.

Community colleges are public schools which offer two-year academic degree programmes. Some of them offer one-year certifcates and two-year Associate Degrees (AA or AAS) in photography. The course of study typically has a practical or commercial orientation, as compared to a fine-art focus, and often emphasizes the technology of photography.

Four-year colleges and universities offer baccalaureate degrees in photography, usually as Bachelor of Arts (BA), Bachelor of Science (BS) or Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA). The BFA degree has a studio art concentration and is generally taught in the art school at the university. The emphasis in a BFA programme is usually personal expression through photography, rather than the technology of photography.

The terminal degree in photography is the MFA or Master of Fine Arts degree, requiring two to three additional years of study beyond the baccalaureate degree. As a fine arts degree, students generally will produce an extensive thematic thesis project. The MFA degree is often a requirement for teaching photography at college level in the United States.

Markets for professional photography

Professional photography, a loose collection of individuals or small units, is structured mostly by the markets for pictures. The main markets are: commercial and industrial; portraits and weddings; press and documentary; advertising and editorial illustration; and technical and scientific applied photography. These are only approximate categories – they often merge and overlap. A photographer in ‘general practice’, for example, might tackle several of them to meet the requirements of his or her local community. Again, you may be a photographer servicing the very wide-ranging needs of a stock-shot library issuing thousands of images to publishing houses or graphic design studios. Then there are specialists working in quite narrow fields – architecture or natural history, for example – who operate internationally and compete for worldwide markets.

Commercial and industrial photography

This covers the general photographic needs of commerce and industry, often businesses in your immediate area but sometimes spread quite widely, as when serving companies within a widely dispersed group. Clients range from solicitors, real estate agents, local light industry and town councils up to very large manufacturing or construction organizations working on an international scale.

Figure 14.3 In commercial and industrial photography you may take photographs that will be used for educational or training purposes.

Your photography might be used to spread a good public relations image of the company. It will be needed to record processes, products and new building developments. Some pictures issued with ‘press releases’ will be reproduced on editorial pages of magazines (often specialist publications). Others are used in catalogues, brochures and internal company reports. Photographs may be an essential element in a staff-training scheme, or needed as legal evidence or for archival records. Work will extend beyond supplying photographs, and is likely to include video work and sequences for presentation in some form of multimedia. When your client is a company, it is important to ask for information on the company’s image and publicity policy.

Owing to the wide range of subjects that you may have to cover in commercial and industrial photography (promotion of varied services and products, public relations, staff portraits, etc.), you may have to work on location or in the studio and you must have very good skills in several types of photography, such as still life, editorial photography or portraiture. On the other hand, you may want to specialize only in one type of commercial photography. Large commercial/industrial studios dealing with many public relations commissions may offer a total communications ‘package’. This teams up photographers, graphic designers, advertising and marketing people, and writers. The result is that a complete campaign, perhaps from the launching conference (announcing a new product to the client’s sales force), through press information, general and specialist advertising to brochures and instruction manuals for the client’s customers, can all be handled in a coordinated way ‘in-house’. Development of electronic imaging encourages ever-larger amounts of brochure and catalogue photography to take place within graphic design studios. Here, it is conveniently fed direct through desktop publishing channels into layouts for the printed page (see Chapter 13).

A few industrial organizations run their own small photographic departments employing one or more staff photographers (see Chapter 15 on working as a staff photographer). As a staff photographer you may be involved in different types of photography, depending on your employer. For example, you may work on public relations, scientific photography, portraiture or still-life photography. Since they work for a specific company, staff photographers have knowledge of the media for which the images will be used and the company’s publicity policy. They are also familiar with the company’s personnel and its geographical layout. Such departments may be general purpose or form part of a larger public relations unit.

Fashion photography

As a flashion photographer you must have an interest in flashion and an understanding of the creative work of flashion designers. You are commissioned for publications (magazines, newspapers and companies), and you are briefed by the editor on the required style of the images and the output media. The briefng may be very specific or, in other cases, more open, allowing you to use your creative skills and produce innovative images. You work with a team which may include models, stylists, make-up artists, hairdressers, set builders, painters and assistants with different specialties. In flashion photography it is important to understand not only the properties of the fabric, but also the concept of the flashion designer, the style of the clothes and the client’s image. You must therefore be creative and keep up to date with current trends in flashion and styles in photography. Experimenting with different styles and techniques contributes to developing innovative images. Technical skills are also important to produce high-quality images in flashion photography. Correct lighting is essential to show design aspects of the clothes and the properties of different types of fabrics. If you create photographs for clothes catalogues, you will have to produce a large number of images quickly, in a stylish way. You work either on location or in the studio.

Portrait and wedding photography

Professional businesses of this kind deal with the public directly. Some operate out of high street studios, but because so much of the work is now shot on location (for example, portraits ‘at home’) special premises are not essential. Some businesses operate from inside departmental stores, or link up with dress/car rental and catering concerns to cover weddings. In all instances it is important to have some form of display area where your best work can be admired by people of the income group you are aiming to attract.

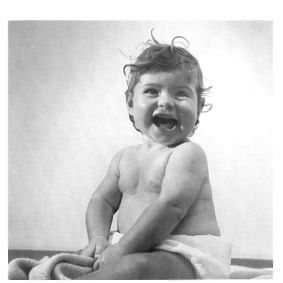

Figure 14.4 Portrait taken in the child’s home using a pair of flash units. A camera with waist-level finder makes it easier to shoot at floor level.

To succeed in photography of this type you need an absorbing interest in people and the ability to flatter their appearance rather than reveal harsh truths about them. After all, it is the clients or their closer associates who pay your bill – unlike documentary or advertising pictures commissioned by magazines or agencies. The people you arrange in front of the camera require sympathetic but frm direction. It helps to have an extrovert, buoyant personality and the ability to put people at ease (especially in the unfamiliar environment of a studio) to avoid self-conscious or ‘dead’-looking portraits.

The work typically covers: formal portraits of executives for business purposes; family groups; weddings; animal portraits; and sometimes social events and front-of-house pictures for theatrical productions (see Chapter 12) (Figure 14.4).

Press photography and documentary

Press photography differs from documentary photography in the same way as single newspaper pictures differ from picture magazine features. Both are produced for publication and therefore have to meet frm deadlines. However, as a press photographer you usually have to sum up an event or situation in one final picture. You need to know how to get quickly into a newsworthy situation, seek out its essence without being put off by others (especially competitors) and always bring back technically acceptable results, even under near-impossible conditions.

Many press photographers work for local newspapers. Where there is relatively little ‘hard’ news, you work through an annual calendar of hand-shaking or rosette-waving local events, plus general-interest feature material which you generate yourself. Other press photographers work as staff on national or international papers where there is keen competition to cover public events (see Figure 14.5, for example). However, most ‘hot’ news events are now covered by television, with its unassailable speed of transmission into people’s homes. With digital cameras you have the ability to get pictures back to base wirelessly which is helpful, but newspapers still lose out due to the time needed to print and distribute them to their readers.

More photographers are employed by, or work fireelance (see Chapter 15) for, press agencies. These organizations often specialize – in sport, travel, personalities, etc. – or handle general-interest feature material. The agency’s job is to slant the picture and written material to suit the interests of a very wide range of different publications and sell material to them at home and abroad. For pictures which are less topical, this activity merges with stock-shot library work, able to generate income over a period of years.

Documentary photography refers to work allowing you more of an in-depth picture essay, shot over a longer period than press photography and aiming to fill several pages in a publication. In the past this has been called photo-journalism, through its use in news magazines, but has now fallen into decline. Other outlets continue, however, including corporate house journals and prestige publications from leading names in oil, fnance, shipping, etc.

As a documentary photographer you should be able to provide well-rounded coverage of your story or theme. For example, bold start-and-finish pictures, sequence shots, comparative pairs and strong single images all help a good art editor to lay out pages which have variety and impact. (On the other hand, a bad art editor can ruin your set of pictures by insensitive hacking to ft them into available space.) One way into this area of photography is to find and complete a really strong project on your own initiative and take it to editors of appropriate publications for their opinions and advice.

Figure 14.5 Shooting pictures at a press conference often means tough competition from fellow photographers and television. It is difficult to get something striking and different. Showing the whole situation like this is one approach. By John Downing/Daily Express.

Editorial and advertising photography

Editorial illustration means photography (often single pictures) to illustrate magazine feature articles on subjects as diverse as food, gardening, make-up, flashion, etc. It therefore includes still-life work handled in the studio. For each assignment the editor or the picture editor of the magazine, book, newspaper, website, etc. will brief you on the story for which you have to produce images, and the type of images they need according to the specific target group of readers. You have less scope to express your own point of view than is offered by documentary photography, but this allows more freedom of style than most advertising work. You have to be organized and work under tight deadlines, producing high-quality images. Editorial photography in prestigious magazines and books is a good ‘shop window’ for you and can provide a steady income, although it is not usually well paid.

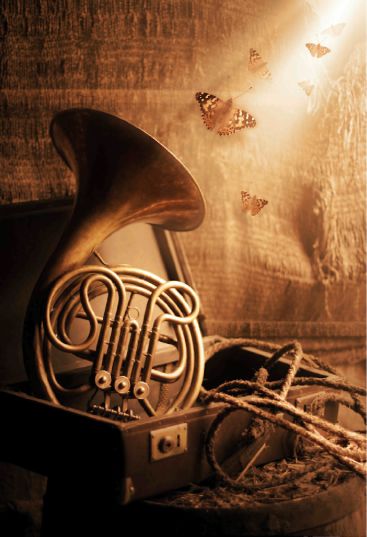

Advertising photography is much more restrictive than outsiders might expect. At the top end of the market, however, it offers very high fees (and is therefore very competitive). As an advertising photographer you must produce images that communicate a marketing concept. The work tends to be a team effort, handled for the client by an advertising agency. You must expect to shoot some form of sketched layout, specifying the height-to-width proportions of the final picture and the placing of any superimposed type. Ideally, you will be drawn into one of the initial planning stages with the creative director, graphic designer and client, to contribute ideas. Sometimes the layout will be loose and open – a mood picture, perhaps – or it might be a tight ‘pack shot’ of a product, detailed down to the placing of individual highlights. At the unglamorous lower end of the market, advertising merges into commercial photography with an income to match.

Whether or not you are chosen as a photographer for a particular campaign depends on several factors. For example, is your approach in tune with the essential spirit required – romantic, camp, straight and direct, humorous? Depending on the subject, do you have a fair for flashion, an obsession for intricate still-life shots, skill in organizing people or in grabbing pictures from real-life situations? Have you done pictures (published or folio specimens) with this kind of‘feel’ or ‘look’ before, even though for some totally different application? Do you have any special technical skills which are called for, and are you careful and reliable enough – without lacking visual imagination? Can you work constructively with the team, without clashes of personality? Finally, are your prices right?

Most of these questions, of course, apply to the choice of a professional photographer for any assignment. However, in top advertising work the fnancial investment in models, locations, stylists and designers (as well as the cost of the final-bought advertising space) is so high that choosing the wrong photographer could be a disaster.

Art photography

Art photography shares concerns with other photographic occupations; the artist must have a product, a market and an audience. Many artist photographers are graduates of national art colleges and university courses, and have a thorough background in historical and contemporary conceptual art practice as well as a critical awareness of art history and theory. The product, the art works, will be driven variously by a commitment to a particular theme or visual strategy and may be linked to a particular social observation or critique. The successful artist must find curators and galleries interested in showing his or her work and an audience wishing to buy it. Some artists are supported by educational establishments, which provide a framework for dissemination of ideas through teaching, offer time and assistance both to make research grant applications for funding and support to produce work. Some make a reputation in the art market through an appropriation of their existing commercial practice – documentary and flashion photography is frequently repackaged as an art commodity by national and private galleries. Equally, artists are often commissioned by commerce, advertising and the flashion industry to keep their products ‘at the cutting edge’ and to associate them with the art world.

Figure 14.6 The choice of lighting, subject and composition is important when you want to create images with a specific mood and communicate a marketing concept.

The ability to present ideas verbally and in written form, informed by contemporary debates, is often an essential skill. This is both to persuade curators of the value of the work, and to make complex and articulate funding bids, as well as to lecture and write in support of the exhibited work. It is also essential to have an eye on the current art market to see which forms of presentation are favoured and to note which shows are in preparation so that work can be targeted at key galleries and publications. ‘Social capital’ – the business of getting to know people in the art world and markets and networking with them – is invaluable in keeping the artist and their art in the minds of commissioners, exhibitors and buyers.

The most powerful and infuential art works are created from a sense of passion about the subject matter and a commitment to reach an audience to raise concerns and interrogate the world of images and issues.

Technical and scientific photography

This is a very different area, where meticulous technical skills and accuracy are all-important. Any expressionism or original personal style of your own will tend to get in the way of clearly communicating information. Photographs are needed as factual, analytical documents, perhaps for forensic or medical evidence, military or industrial research and development. You will probably be a staff photographer employed by the government, a university or an industrial research institute. Photographic skills required include photomacrography, photomicrography, infrared and ultraviolet photography, photogrammetry, remote sensing, thermal imaging (Figure 14.7), high-speed recording and other forms of photo-instrumentation, including video. There is also a great deal of routine straight photography on location and in the laboratory.

You will be expected to have more than just photographic know-how. As a clinical photographer, for example, you will most often work in a hospital’s medical illustration department. In addition to photographic skills in several applied imaging areas, you need a working knowledge of anatomy, physiology and an understanding of medical terms, as well as concern for patients and an interest in medicine generally. You may also take photographs of the hospital staff and facilities or public relations photographs. As a scientific photographer you should have a sufficiently scientific background to understand advanced equipment and appreciate clearly what points scientist colleagues want to show in their reports and specialist papers. As a police photographer you should be thorough and pay attention to detail, use suitable

Figure 14.7 An example of the appearance of a thermal image. This is a photograph of a thermal image screen.

lighting techniques and give correct exposure. The images must be sharp and with maximum depth of field. You must be able to work with accuracy and keep a detailed record of the scene photographed, the lighting conditions and the equipment used. You should also know what is or is not admissible in law and how to present evidence effectively to a court. On top of this, you must assess the potential of all new photographic materials and processes which might be applicable to your field. You will also be expected to improvise techniques for tackling unusual requirements.

To be a good ‘applied’ photographer you should therefore enjoy a methodical, painstaking approach to solving technical challenges. You will probably be paid according to a fixed, national salary scale, which is not particularly high. However, there is better job security than that offered by many other branches of professional photography.

Roles within a photographic business

Perhaps you are a one-person fireelance or one of the team in an independent studio or in-house photographic department. Every professional photography business must combine a number of skills, and for each skill you might require an individual employee, either on the payroll or ‘bought in’ (by using an outside custom laboratory, for example). For the lone fireelance several or all of the following roles have to be filled by one person.

Manager/organizer

Managing means making sure photography goes on efficiently and economically. You must hire any necessary staff and/or outside services, check that quality control and reliability are maintained, and watch fnances. Like any other administrator, you will be concerned with: safety; premises; insurances (including Model Release, page 426); and best-value purchase of equipment and materials. You must know when to buy and when to rent items. Every assignment must be costed and charged accurately, remembering the competition and producing the work as economically as possible without dropping standards. As a manager, you must understand essential book-keeping and copyright, and be able to liaise with the accountant, bank manager, tax inspector and lawyer. If you employ staff you must be concerned with their health and safety, as well as have the ability to direct and motivate them, creating a team spirit and pride in the photography produced.

Photographer

Ideally, a photographer should be free to take photographs. In practice, apart from being technically reliable and visually imaginative, you must be a good organizer and also be able to liaise directly with the client. Dealing with whoever is paying for your services is harmonious enough if you both see eye to eye, but unfortunately clients have odd quirks of their own. When it is obvious that this will lead to disaster (for which the photographer will eventually be blamed), considerable tact and persuasiveness are needed.

At a pre-briefng you should identify what the client has in mind, or at least the purpose of the picture and how and where it will be used. If the brief is very open-ended, foat some ideas of your own and see how cooperatively these are received. If still in doubt, do the job, photographing the way you would like to see it done, but cover yourself by shooting additional (for example, more conventional?) versions the client might expect. Often in this way you can ‘educate’ clients, bring them around to using more distinctive photography. But never experiment at the client’s expense, so that they end up with results they cannot use. As a photographer, you should carry through each of your jobs whenever possible – if not printing yourself then at least supervising this stage. Finally, discuss the results directly with whoever briefed you in the first place.

Technicians

Technicians provide photographers with back-up – processing, printing, special effects, finishing – to turn camera work into final photographs. Technical staff are employed full-time or hired as and when required for jobs, some as fireelances or, most often, through their employment in professional custom labs. Technicians have specialized knowledge and skills highly developed by long practice in their particular area. Equally, they can offer new skills such as digital manipulation, producing what the photographer needs much faster than he or she can do alone. For a technician with specialized digital imaging skills, the photographer can refer to a digital imaging specialist. Technicians often give photographers valuable advice before shooting, and sometimes bail them out afterwards if some technical blunder has been made.

Working as a technician is sometimes creative but more often routine. You must produce work quickly, and to the highest professional standards. In return, there is more security and often better pay in being a first-class technician than an ordinary photographer. Too many people want to be photographers, overlooking equally satisfying jobs of this kind.

Digital imaging specialists

The digital imaging specialists work in professional laboratories and are responsible for the whole workflow, from file downloading and scanning of images to colour management and image output. You are specialized in digital image manipulation using software packages such as Adobe Photoshop, and have an in-depth understanding of photography. You may also be involved in layout design and so need to have knowledge of relevant software packages such as Quark or Adobe Illustrator. Digital imaging specialists should also have knowledge of digital image archiving and image restoration. It is essential to update your knowledge of current developments in colour management, imaging devices, and calibration tools and methods. Accurate calibration of all equipment such as scanners, displays and printers is essential for accurate reproduction of the images throughout the imaging chain (see Chapter 7). Digital imaging specialists may also work in picture libraries, where they need to have additional skills in archiving and image databases.

Ancillary roles

Supporting roles include photographer’s agent – someone who gets commissions for you by taking and showing your work to potential clients. Agents seek out jobs, promote you and handle money negotiations. In return, they are paid a percentage of your fees. Stylists can be hired to find suitable locations for shots, furnish a studio set or lay on exotic props. Model agencies supply male and female models – attractive, ugly, ‘characterful’, young and old. Specialist photographic/ theatrical sources hire trained animals, uniforms or antique cars for you – everything from a stuffed hyena to a military tank.

SUMMARY

- Being a professional makes commercial factors – reliability, fast economic working methods and good organization – as important as your photographic skills. Often, you have to create interesting pictures within a quite restrictive brief.

- To progress beyond a certain level in photography, you need to learn how people read meaning from photographs – single pictures or sequences. Understanding how your work is likely to be received will help you to decide the best approach to your subject.

- Professional photography is mostly market structured – commercial and industrial, portraits and weddings, press and documentary, advertising and editorial, and technical and scientific.

- Commercial/industrial work covers promotional and record photography for frms and institutions. Your photography may be part of a complete communications ‘package’, including brochure design. As a flashion photographer you should produce innovative images and you need to understand the ideas of the flashion designer and the properties of the fabrics. Portrait/ wedding photography is aimed directly at the public. You need to be good at flattering people through your photography and general manner.

- Press photography, very time-based and competitive, means summing up a newsworthy event. Some publications still accept visual essays, offering space for in-depth documentary coverage of a topic. You can therefore think in terms of sequence – supply the art editor with full coverage containing strong potential start-and-finish shots.

- Editorial/advertising photography means working close with designers. Catalogue work, particularly, justifes the use of digital studio photography direct to desktop publishing (DTP). Advertising work is heavily planned – you usually work on a layout within a team, including a creative director, a graphic designer and a copywriter. You must be organized to meet tight deadlines.

- In art photography the product is driven variously by a commitment to a particular theme or visual strategy. The theme may be linked to a particular social observation or critique. It is also important in most cases to have the ability to present ideas, informed by contemporary debates, in both verbal and written forms.

- Technical/scientific applications of photography call for factual, analytical records. You are likely to be an employed staff photographer, either working on industrial/university research projects or at a forensic or medical centre.

- There are several key roles in any photographic business or department. A manager administrates quality control, accounts, safety, equipment and materials. One or more photographers organize shoots, liaise with clients and carry out jobs efficiently, imaginatively and economically. Technicians follow through the photographers’ work and service reprint orders. Digital imaging specialists work on file transfer, image manipulation, colour management and archiving of images. Ancillary roles include agent, stylist and agencies for models, props, etc.

- Most people get into professional photography by taking an appropriate fulltime college course, or they start in a studio and study part-time. However, ‘getting on’ depends more on evidence of your practical achievements than on paper qualifcations.