15 Business practice

This chapter aims to provide an introduction to some important aspects of photographic business practice. An attraction for many people when choosing to work in photography is the degree of freedom and fexibility offered by self-employment; however, a certain degree of skill and knowledge is necessary to make a successful living from working in this way. There is not a guaranteed regular income, protection in terms of employment law, paid annual leave, sick leave and other employment benefits which are part of employment within an organization. At certain times in your career, you may be employed as a staff photographer, or you may do both that and work as a fireelancer, combining part-time work for an organization with your own business. Depending upon the type and size of your business, you may employ others to work for you. Business practice varies with the nature of the work and the location, but there are certain aspects common to all types of photographic practice that are important to be aware of. These enable you to protect yourself and the people working for you, your work and your equipment, and to ensure that your business runs smoothly and is successful. This chapter aims to identify these areas, provide a general overview and a foundation from which you may research the specifics for your own business practice from relevant sources relating to your area. There are numerous useful publications covering business practice in photography in more detail. Many professional associations produce publications covering practical and legal considerations for a particular type of photography; therefore, these can be a good starting point.

Starting out

Most photographers do not rely solely on fireelance work until they have established themselves to some extent. Initial photography jobs may not be paid, but used to build up a portfolio. This requires that you have an alternative source of income to fall back on as you begin to work in photography. These may be activities unrelated to photography, but it makes more sense to begin working in an image-related area if possible, simply because it can provide valuable insight into the industry.

Starting gradually also allows you to build up some capital, vital at the beginning, as, depending upon the area that you are working in, the nature of commissioning means that some jobs may not be paid for several months, and you will need to be able to cover your overheads and living expenses in the meantime. The alternative to having initial capital is a bank loan; this necessitates a well-defined business plan. Needless to say, the current fnancial climate in the wake of the global recession means that obtaining small business funding is both more difficult and more expensive than previously. However your business is initially funded, it is important to have a clear idea of your aims and objectives before you begin, including the type of work that you will be doing, your target audience, equipment required, how your work will be marketed and any additional start-up costs, such as rental of equipment or premises.

Working in the industry, for example as a photographer’s assistant, allows you to begin to establish a network of useful contacts. It is important to remember that, vital as self-promotion and marketing is in running a successful business, the people that you get to know are also a key resource. The majority of photographic industries, whatever the type of imaging, are built on communication through networks and via word of mouth, from those commissioning, buying and using the images, to the photographers themselves, the people working with the photographers (assistants, models, retouchers), and all the companies supplying the industry with services, materials and equipment. Establishing relationships with the organizations and people that will be relevant to your practice will save you huge amounts of time and money in the long run.

As well as networking, working in the industry before going completely fireelance allows you to test and develop your skills. For this reason, many photographers start out by assisting other photographers, learning from the way they work and using the opportunity to practise and improve in their use of equipment, as well as learning about the way the business operates.

Working as an assistant

The tasks involved as a photographer’s assistant will vary depending upon who you are working for and the type of work they do, particularly on whether it is location work or mainly studio based. It may involve anything from checking equipment, loading film, downloading images, processing RAW files and backing up, or setting up lights, to maintaining studios, meeting and greeting clients, and sending out invoices.

You will need basic photographic skills and an understanding of different camera formats. Having knowledge of digital technology and some basic image adjustment and retouching skills is also useful, particularly as many photographers have now made the complete transition from film to digital. Some understanding of basic colour management and digital workflow can also be a huge advantage, although you will pick up a lot of practical knowledge during your assisting work. Being motivated, reliable and able to learn quickly are often more important qualities than having advanced knowledge of, for example, lighting techniques, which you will learn, particularly if working in a studio environment. Many assistants begin when they are still at college. Volunteering to work for an initial few days for firee, or arranging a week’s work experience, can be a way of getting your foot in the door. If the photographer likes you, they may offer you more days or even something more permanent. Photographers may be happy to take on relative beginners, as long as they show that they have the right attitude, are willing to learn and get on with them – after all, that is how many of them will have started out.

There are a few golden rules that are useful to keep in mind when working as an assistant, which will help to ensure that you get used again. Some are basic common sense: arriving early, being prepared and properly dressed for the job and turning your mobile off, or on to vibrate while working, help to demonstrate that you are reliable and taking the work seriously. Others are more about how you relate to the people that you work for. Listen carefully to the photographer; they should tell you what they expect. Never question the way a photographer does something, e.g. setting up focus, lighting or camera settings, unless there is something that they need to know immediately to prevent a problem. Examples of this might include strobes not firing, or the computer crashing. And be sure to let them know straightaway if you break or lose something! Don’t let them find out later. When there is a practical problem raise it with the photographer quietly, not within earshot of a client. Aim to present a united and professional front as part of their team at all times. Show that you are alert and interested in what you are doing, and that you want to learn. Many photographers love to help assistants, having started in the same position themselves. Ask plenty of questions about how and why they have done things, but do this when clients are not around. If the client is there throughout the shoot, then make notes and ask the photographer after the job is finished.

Many commercial photographic associations have systems to put photographers in touch with prospective assistants, or they may advertise assisting jobs, either for short-term assignments or more long-term positions. Generally the work will be paid according to a day rate and based on your level of experience. The rate of pay also depends on the type of work. Advertising photography, being the most lucrative area, pays much better than most other areas. It is worth finding out what the going rate is from other assistants or relevant associations and agreeing this beforehand.

As an assistant, you will usually be working on a fireelance basis and will work as and when the photographer needs you. The work will not be arranged around your availability; therefore, it is worth trying to find work with a number of different photographers. This requires that you are fexible and prepared for quiet periods and a relatively low income. However, this allows you the freedom to use your spare time to work towards your ultimate goal of working as a photographer rather than an assistant. Get as much in terms of your training out of the times that you are working and use the time when you are not to develop your portfolio. This should be an ongoing process; you should be constantly reviewing and updating it. Fashions in photography change, as does the way in which the work is presented. Looking at other people’s work, fellow assistants, photographers, websites, magazines and exhibitions will provide inspiration. You may decide that you need more than one portfolio, depending upon who it is aimed for, or you may have a pool of images (which you can constantly add to) that you can chop and change to tailor the portfolio to the person you are showing it to. You should also have your own website – but ensure that it is well designed and easy to navigate. This can be used to showcase a much larger range of your work divided up into different categories and genres. Providing a link to this on all correspondence is a great way to get your work seen by a larger audience.

As an assistant you may have opportunities to use or create images which you will then put in your portfolio. It is vital if you are using someone else’s equipment that you have the agreement beforehand and are clear about the terms of use. The same rules in terms of legal requirements and insurance apply as if you are working as a photographer, particularly governing working with other people. You will need to make sure that you are adequately covered in terms of Employers’ Liability insurance in particular (see later in this chapter for more details). If you are assisting a photographer in an organization and are using their equipment and facilities, you must also be very clear about copyright ownership. Occasionally you will come across an organization that specifes in their contracts that they own the copyright of any images taken using their resources; it is obviously best to avoid this, as you need to maintain your own copyright wherever possible.

Because assisting work varies so much, it is difficult to generalize about the business aspects, but this is the time to get into some good habits, as these will be just as useful when you are working as a photographer. Basic book-keeping, where you track jobs, invoices and expenses, is a fundamental skill. Keeping records of jobs, writing things down and obtaining confirmation are also important and will make your life much easier, as you will see, particularly if anything unexpected happens. At the very least, you should become accustomed to ensuring that you clarify the terms of a job before you start: the dates, length of time, and payment of fees and expenses. This means that both you and the photographer will be clear about what you expect from each other, misunderstandings are less likely to happen and you are more likely to be booked again.

Becoming a photographer

Working as a fireelance photographer

Whether you start out as an assistant or work in another area as you are establishing yourself, the process of becoming self-employed and supporting yourself through your photographic work may well take several years. Building up a client base may require that you begin by taking on some jobs for firee. This should not be viewed as a waste of time, however; you never know when you are likely to come across someone who really likes your work and not only re-books you but recommends you to someone else. You will also be producing work for your portfolio as an ongoing concern.

During this time you will need to work out what area of photography you want to work in. If assisting as well, try to work with as many different photographers as possible, to gain experience of the many different commercial classes of photography – for example, food, flashion, product, advertising, jewellery, catalogue, people, editorial. Decide what area is your passion and from this you can perform a skills audit, identifying what you need to know and where you need to improve. This will also identify how you go about obtaining work and finding clients.

For example, the skills required to become an architectural photographer are highly technical, such as the use of larger format equipment, the ability to light interiors and create mood (see page 351). The photography may be either advertising or editorial and you will need to network with people already involved in these areas, contact organizations and agencies requiring these sorts of high-quality images, and probably to assist photographers also working in architectural photography. You will need to be taking your portfolio to art directors and picture editors for relevant publications. How you go about this will depend upon the way the industry works in your geographic location.

The skills required by a photo-journalist are somewhat different, however. This type of photography is less structured and more immediate. It tends to be predominantly smaller format and there is a much greater emphasis on candid images, seizing the moment and being in the right place at the right time. Where editorial and advertising photography will often involve an entourage of people in any one shoot, photo-journalists work mainly on their own. There is not the time available that there is in more formal photography, for detailed image retouching, possibly by someone else. The photo-journalist these days works mainly using digital equipment from capture to output, with a laptop to process and retouch the images before transmitting them wirelessly, as important a part of their everyday kit as their camera. The skills required are more geared towards this way of working. Fundamental to such work is the ability of photographers to think on their feet and to be able to constantly adapt as a situation changes or a news story breaks (see also Chapter 12).

You will find that the conventions for getting your work seen differ depending upon where you are and the sort of photography and the level of competition for that type of work. For example, the highly competitive environment in London or New York means that you may not have face-to-face access to picture editors and will have to leave your portfolio for them to have a look at, in the hope that something in it will catch their eye and they will call you back. In a smaller city elsewhere in the world, things may work differently, with a much more personal approach and the ability to sit down and talk through your portfolio with the relevant people.

Any type of photography that is ultimately going to be published in magazines or newspapers is likely to require that you seek out and get your portfolio seen by the right people. However, the area you decide to specialize in will define the people that you need to get to know and the way in which your work should be presented. Presentation is extremely important if the final output is in advertising or something similar. Promotional (‘promo’) cards are a good way to show your work to potential clients. Many photographers print cards or small books of their work to send out speculatively. As for an assistant, having a good website is a vital marketing tool for a photographer and an easy way to get your work in front of people. Do some research and find out whom to make contact with, the name of the relevant art buyer or art director. Get in touch with them, sending a link to your website and ensuring that your contact information is included. Follow this up with a further phone call or email. Find a balance between being persistent without being intrusive.

For photo-journalism, however, the style, content and relevance of your images, and the speed at which you get them seen by a picture editor, are often more important than more long-term marketing (although you should not neglect the strategies mentioned above). News photography in particular relies more and more on the publication being the first to obtain the rights to the image. Many photo-journalists will go out on speculative shoots, following a particular news story, trying to get a decent image and then being the first to get it to a news desk (Figure 15.1). You may therefore first get noticed by a picture editor through a specific image that has been emailed in connection with a news story rather than through a portfolio. A lot of money can be made if the image is covering an important news item, but obviously these types of images have a short shelf life. If someone else gets the image to the picture desk first, even if it is of lower quality or not as good a shot, and that image is published, particularly on the web, then it may render your image redundant, however good it is.

On a final note, when you are establishing yourself in a certain market, it can help to find a representative, or agent, who will help to sell your work. Although you will pay a percentage of your fee if they get you a j ob, this can take some of the effort and legwork out of marketing yourself. Many photographers are not so good at self-promotion, whereas representatives already have the network of contacts and the negotiation skills. They will set up appointments with clients and show your work. Some representatives will have a collection of photographers covering different types of work. In finding the right person to represent you and your work, it is often helpful to make contact with other photographers and find out who they are represented by.

Figure 15.1 Photographers waiting for Sir Elton John and David Furnish to leave Windsor Guildhall after their civil ceremony, Wednesday, 21 December 2005. Freelance press photographers often go out on speculative shoots, covering local events or current news items. They will then email the image to all newspapers for a prospective sale. There is a lot of competition when working in this way – it will often depend upon who gets their image of an event to a picture desk first. Image © James Boardman Press Photography (www.boardmanpix.com).

Working as a staff photographer

An alternative to starting out on a self-employed basis is to become a staff photographer for an organization. There are a number of areas where this is more common – for example, local newspapers will often employ photographers on a more permanent basis. Other fields include forensic photography for example, or clinical photography. There are advantages to starting out or working in this way, as the organization will offer the same rights to a staff photographer as to any other employee. Although you sacrifice the freedom and fexibility of fireelancing, you are afforded protection in a number of ways, and have paid holiday, annual leave and a steady income. Additionally, the organization will often buy your equipment for you, which can be a godsend if you require expensive digital kit. Your overheads will also be covered – for example, materials and communications costs; in some cases a company car may even be provided.

This all sounds rather comfortable, but employed photographers do not tend to have the same earning capacity as fireelancers. Another key issue is that of copyright. You will be tied in by a contract and this may well state that the organization not only owns the copyright on any images that you take for them, but also on any images that you take for yourself using their equipment and facilities. In the more scientific fields, however, you may not have any alternative as there may not be the option of working as a fireelancer; the organizations simply do not work like this.

The issue of whether you want to be employed or fireelance is therefore another consideration when deciding on the area that you are going to work in. Certain photographic specialisms rely solely on employed photographers and this may be something that you are happy to do, either because you appreciate the security or because you are very clear that this is the type of photography you wish to do.

Alternatively in some locations you can choose to work as an employed photographer in a studio as an intermediate stage to become fireelance. There can be advantages to this, particularly if employed by a large studio, as most have representatives who work full-time for the studio and represent all the photographers’ work. These are sales people who will include your work with that of other photographers at the studio, to present the range of what the studio can offer in terms of talent and expertise. To summarize, there are a number of aspects common to the process of becoming a working photographer, once you have decided what type of photography you are going to work in. These include purchasing equipment (unless working as a staff photographer), gaining experience in your chosen field, identifying and obtaining required skills, creating and updating your portfolio and getting your work seen by the relevant people, either future employers or future clients. Although the details may vary, the qualities required are similar: to work in photography, whatever the field, you need to be highly motivated, organized and creative both in your work and in your approach to business. You also need patience and persistence. Although technical skills and creativity are of primary importance, personality plays an essential role in achieving success as a practising photographer. Sheer grit and determination may be necessary at times to ensure that your work gets seen. You must believe in yourself and be prepared to market yourself and your skills. You must also be prepared for knock-backs; it may take some time before you start to sell your work.

Running a business

To run a photographic business successfully you have to master certain management skills, even though you may work on your own. Some of these activities are specifically photographic but most apply to the smooth running of businesses of all kinds. If you are inexperienced try to attend a short course on managing a small business. Community colleges are a good resource for classes. Often, seminars on this theme are run by professional photographers and associations. There are also many user-friendly books and videos covering the principles of setting up and running your own business enterprise.

Many photographers choose to operate their businesses as sole traders, known in the USA as sole proprietorships. This is the simplest method and offers the greatest freedom. The photographer interacts with others as an individual, has sole responsibility in making decisions, but also personal liability for debts if the business fails. It is vital if working in this way that you separate business from personal fnancial transactions, having a separate business account. It is also important to ensure that business costs are met before personal proft may be taken. When working as a sole trader/proprietor, discipline is necessary in keeping track of income and expenditure. Book-keeping need not be complicated, particularly if you hire an accountant to do your end-of-year returns, as long as you set up some sort of system and use it consistently.

An alternative method of business set-up is some sort of partnership. This can be a useful way to share the resources and start-up costs. The way in which the industry has changed since the use of the Internet and digital technology has become more widespread means that it can be useful to offer a range of services alongside photography, such as the design of graphics or web pages, and the scanning, retouching and compositing of images. Some photographers have expanded their skills, meaning that they can offer some of these additional services themselves, but a partnership can be a useful way for several fireelancers with different skills to work together. In partnerships, the partners are jointly liable for debts. This can be an advantage, as the pressure is taken off the individual; however, it is important that all partners are very clear from the outset on the terms of the partnership and responsibilities involved in the business. The business relationship should be defined legally and ideally partners should try to discuss possible issues that might arise and how they will be dealt with, before the business is set up.

The most formal method of running a business is to set it up as a company (in the UK) or corporation (in the USA). This is less common; it tends to happen more with businesses with a higher turnover. Advantages include the removal of individual liability should anything go wrong, and the fact that the business will remain should an individual choose to leave (which can be a problem in less formal partnerships). However, running a company or corporation is significantly more complex; more administration and organizational procedures are involved and it may be more laborious and time consuming to make long-term decisions. Whether you operate as a sole proprietor, in partnership or as a corporation, each has different tax implications and these should be discussed with your accountant.

Book-keeping

Book-keeping fundamentally involves keeping a record of any fnancial transactions to do with the business, incoming or outgoing. However photographers choose to operate their business, book-keeping will be a fundamental part of the day-to-day management. Many photographers, particularly those working as sole traders, will manage the process of book-keeping themselves, but pay an accountant to deal with their books at the end of the year to calculate their tax returns. This may sound the dullest aspect of professional photography. But without well-kept books (or computer data) you soon become disorganized, inefficient and can easily fall foul of the law. Good records show you the fnancial state of your business at any time. They also reduce the work the accountant needs to do to prepare tax and similar annual returns, which saves you money.

Having set up a separate business bank account, it is necessary to keep a record of income and expenditure, have a method for tracking and archiving invoices and somewhere to keep receipts. The process of recording can be performed in some sort of accounting software, but can be as simple as a spreadsheet on which income and expenditure are entered on separate sheets on a regular basis. A fling system can then be set up corresponding to this, to store the hard copies of receipts and invoices, to be passed to the accountant at the end of the fnancial year.

A large aspect of your book-keeping will be to record individual jobs. You will need some sort of booking system which may be separate to your accounts, but for fnancial purposes you need to record all the jobs in terms of their invoices. The expenses associated with each job should in some way be linked to the invoice, both in software and in hard copies. The client will usually be charged for the majority of expenses (such as materials, processing, contact sheets, prints, and transport and deliveries) associated with a job. Expenses will appear as money coming into the account but they are not counted as income as you will have spent money up front for them and are simply claiming it back from the client, so it is important that they are identified and not taxed.

When you prepare an invoice, you should record the invoice number, client name, a description of the job, the date, amount and expenses. When the invoice is paid, you should then identify it as paid in your invoice record and include the date, amount and method of payment. Alongside this, you need a receipt book, in which to record payments received from customers. After giving the customer a receipt, record the receipt number in the invoice record. You may prefer to create your own receipts electronically, but must make sure that you back them up. Receipt books may be a simple option as they allow you to keep a record of all the receipts you write out in one place.

Alongside your computer records of invoices, you should also keep hard copies of invoices in a fling system. A simple method can be to file all information from the job together, which makes it easy to access and means that you do not have many different fling systems. You could, for example, include the original brief (if there was one) and any notes you made at the time, confirmation from the client (printed out if by email), delivery note, model release forms, contract, copies or record of receipts (originals should be kept elsewhere, as they will need to be submitted to the accountant), invoice and captions. Jobs can then be filed in date order and possibly by client if they regularly commission work from you. If you then have any queries you can go back and see all the details in one place.

You should also keep a separate record of outgoings in terms of purchases of goods and services. You can simply list all suppliers’ invoices, with a note of what they are for, the date, and when and how they are paid. You can link this to your depreciation record (see below).

For small purchases that you may buy from time to time, for example stationery, which are not to be associated with a particular job, it is useful to operate a petty cash box in which you keep a cash fund. Each time you pay for something from the petty cash fund, you place the receipt in the box. When the fund is low, you can add up all the receipts on a petty cash sheet and keep them all together, then topping up the fund to its original amount. A petty cash system saves cluttering up your main records with small entries. It also highlights the need to always retain receipts – whether the amount is large or small.

It is vital to maintain records of all main items of equipment. This forms an inventory (for insurance against fire or theft) and allows you to agree a ‘depreciation’ rate for each item with your accountant. For example, a camera may be given a reliable working life of 5 years, which means that its value depreciates by a set amount each year (effectively this is the annual cost to your business of using the camera, and part of your overheads when calculating trading profits for tax purposes).

Insurance

Because photography involves such expensive equipment, you will undoubtedly have given some thought to equipment insurance. It is important to check your policy very carefully, to ensure that it covers, for example, equipment transported in a car and overseas. You should also make sure that you are clear about whether it involves new for old replacement of equipment. The insurance should be enough to cover the value of your equipment, and you should make sure that the maximum for a single item of equipment is adequate and that the single item excess is not impractical for making a claim. It is best to seek out a company specializing in insurance for photographers, as they will tend to have policies tailored to the high value of individual pieces of equipment. Standard contents insurance is usually inadequate for these purposes. In the USA, it is possible to purchase a ‘rider’ to an insurance policy for a job, which is a temporary additional amount to cover a specific item (for example, when photographing something of value, such as jewellery), piece of equipment or person. The client will cover this expense, and the rider will be in effect for the period of time necessary for the job.

There are legal requirements for a working photographer (or assistant) to have a basic level of certain other types of insurance, to protect the business against claims for damage to property or people, or negligence such as mistakes in or loss of images, which lead to additional expenses for clients. These will vary depending upon global location. It is prudent to assume that similar rules will apply, but important to check the legal requirements for the country in which your business is registered. The following is an example of some of the relevant insurance policies available in the UK. It is not exhaustive; check photographers’ associations in your field for more details.

Employer’s Liability insurance

This is a compulsory insurance in the UK if a photographer has anyone working for them, even if they are not being paid. For example, if an employee has suffered an injury while working for a photographer, and the courts decide that the photographer was negligent and therefore liable, then the Employer’s Liability insurance protects the photographer and will meet the costs of the employee’s claim. This insurance covers death, injury and disease.

Public Liability insurance

Similar to the Employer’s Liability insurance, this covers property rather than people and protects the photographer from liability for loss or damage of property, and injury, disease or death of a third party (who is not working for them).

Professional Indemnity insurance

Although optional, this is one of the more essential when working professionally, as it protects against claims of professional negligence. These may be about very minor things, but can cost a business a lot of money. Examples include infiringement of copyright, mistakes leading to a reshoot being required, loss or damage of images, etc.

Charging for jobs

Knowing what to charge often seems more difficult than the technicalities of shooting the pictures. Charging too much loses clients; charging too little can mean periods of hard work for nil proft. It is not seen as good practice to drastically undercut your contemporaries; it can undermine future jobs and would not make you friends. The amount to charge will depend fundamentally on the type of work you do and who it is for.

If the work is commissioned, then you will be agreeing a price up front. Advertising is by far the best paid, but the amount will depend very much on how big the job is, the type of media and the circulation (as well as your reputation, of course). Press photography varies widely – the sky is the limit if you are covering a big story and have obtained an exclusive image which you are able to tout to the highest bidder. Editorial work tends to be more poorly paid, sometimes a ffth or a tenth that of standard commercial rates. For all of the above areas, it will depend fundamentally upon who is buying your image and what the convention is in the region that you work. Newspapers and magazines often have a set day rate, which may be negotiable, but this will be the key determining factor. If you tend to do more commissioned photography for individuals, for example photographing social events, then it is more common for you to set your day rate as a starting point and for the client to then negotiate with you from that.

Working out your day rate

It can be helpful to find out what your competitors are charging before you start and it is useful to be fexible; you may have different day rates for different types of jobs, depending upon their complexity, and also for different types of clients. You may not always work for your day rate (particularly when working for publications that specify their own day rates and are relatively intransient in this); however, it is important to have a rate in mind during negotiations which makes sense for you and your business. It is also an important benchmark for you to help in deciding when to turn down work. It may seem strange to think in these terms, but there will be some jobs where the money on offer will not be enough to cover your overheads or make it worthwhile for you. There may be some situations where you choose to take on this work, but having a day rate which has been worked out systematically allows you to identify these jobs and make informed choices about whether you take them or not. Sometimes it is better to get something new for your portfolio and form a relationship with a new client at a reduced rate. Hopefully in more cases the money offered will be higher than your day rate rather than lower.

Working out a reasonable day rate is based on costing. Costing means identifying and pricing everything you have paid out in doing each job, so that by adding a percentage for proft you arrive at a fair fee. This should prevent you from ever doing work at a loss, and provided you keep costs to a minimum the fee should be fully competitive. Identifying your costs means you must include indirect outgoings (‘overheads’) as well as direct costs such as materials and equipment hire. Typical overheads include rent, electricity, mobile phone, broadband Internet connection, water, cleaning, heating, building maintenance, stationery, petty cash, equipment depreciation and repairs, insurances, bank charges, interest on loans and accountancy fees.

You then need to work out what you want to pay yourself as a salary and any other staffng costs. You must take into account the number of days you are aiming to work over a year, including holidays and the fact that it is unlikely that you will be shooting five days a week, as you will need several days a week for the associated activities in terms of managing your images and managing your business. From this you will be able to work out how much you need to charge a day.

When it comes to costing, you base your fee on a number of elements added together:

1. What the business cost you to run during the time period you were working on the job. This is worked out from your overheads and salary requirements as above.

2.The percentage proft you decide the business should provide. Proft margin might be anywhere between 15% and 100%, and might sometimes vary according to the importance of the client to you, or to compensate for unpleasant, boring jobs you would otherwise turn away.

This provides a basic day rate. Expenses are then added. These are: 3. Direct outgoings which you incurred in shooting (such as the materials and storage media, travel, accommodation and meals, models, hire of props, lab services, image retouching and any agent’s fee).

Because expenses related to the job have already been paid out, these are not part of any proft made and should not be taxed.

Most photographers will charge for a full day however long the job lasts, because some of the day will be taken up with travelling to and from the job and to allow for the time spent in related activities, such as going to pick up prints. It may be worth offering a half-day rate for jobs that are not going to take much time, but it is important to bear in mind that taking these jobs will usually mean being unavailable for other work on that day.

The use of the image should also be a consideration. It is most common for the photographer to retain the copyright and for the usage to be agreed beforehand. Usage specifes how many times an image may be reproduced, in what region of the world and on what type of media. It may also determine whether the buyer has exclusive rights to the image and if so for how long. This is particularly important in news images, as their exclusive rights prevent the reselling of the image and therefore represent a loss of potential proft. The more that the buyer of the image wants to use it, the more the copyright owner should be able to charge for it. This is an important part of the original negotiations and should be confirmed in writing (even if by email) before the image is used. For commissioned work it will usually be written into a contract. This is covered in more detail later in the chapter.

Invoicing and chasing payment

It is necessary to have a consistent system for sending out and chasing outstanding invoices as part of any book-keeping system. All outstanding accounts should be checked on a regular basis to stay on top of things.

To ensure payment for a job, the client must first receive the images and a copy of your terms and conditions – this is important. When sending out images, either soft or hard copies, a delivery note should always be included. The delivery note will also detail your terms and conditions for the client’s use of the image. By accepting the image and the delivery note the client is accepting the associated terms and conditions, and they will be in breach of copyright if they use the image without paying for it and will be liable for legal action. If sending out hard copies, unless delivering them yourself, then use a courier to make certain that the images will be covered by insurance for their safe delivery. If using an alternative method of delivery then the photographer should take responsibility for insuring the images themselves. It is good practice to follow up delivery of the images with a phone call or email to make sure that the client has received them, and send the invoice a few days later.

As well as the information about the job, the invoice should clearly state the payment terms, i.e. how long before the client is expected to pay, for example 30 days. The typical length of time will depend on the type of client and the location. Some clients may take several months to pay; this can be particularly true of newspapers in the UK, whereas others will pay promptly after two weeks.

If all payments are checked on a regular basis, it will be simple to send out monthly statements to clients with outstanding invoices. These can be backed up with regular phone calls. As long as clearly stated terms and conditions are written on a contract and a delivery note, then there should be no problem in obtaining payment eventually. However, you should be prepared for the fact that it may involve a frustrating amount of time spent in chasing them. It is important to follow-up payments which have not arrived; invoices are too easily lost and some companies seem almost to have a policy of non-payment until they are chased for them. It is also important to remember that the person who commissioned the work may be far removed from the fnance department and may have no idea that an invoice has not been paid; in other words, the onus is very much on the photographer to ensure that they get paid, rather than the client.

Uneven cash fow is the most common problem with small businesses, and a partial solution can be to establish a line of credit with your bank. Clients (especially advertising agencies) are notorious for their delay in paying photographers. Often, they wait until they are paid by their clients. It is therefore advantageous to have one or two regular commissions which might be mundane, but are paid for promptly and even justify a special discount. The length of time it can take for payment to come through is something to bear in mind when setting up your business. It may be several months before you see any money coming in and you will need to have some sort of fnancial safety net available to cover this period, enough to cover your living costs and overheads for 2-3 months at least.

Commissioned work

The majority of photographic work is commissioned, i.e. the photographer is booked to produce particular images, rather than speculative (these are images that you shoot without being booked to do so, and then try and sell; they tend to be more common in photo-journalism). Commissioned work will involve several interactions between the photographer and the client before the job is completed and paid for. The formality of this process will depend upon the field of photography and the photographer’s way of working. It is necessary to maintain a system for recording and tracking the progress of a particular commission. Some of this may involve standard forms, either from photographer or client, whereas other aspects might be communicated by email. It is important to keep written records of all communication and to be able to easily access information relating to a particular piece of commissioned work.

Job sheets

One good way of keeping track of a job in progress (especially when several people are working on it at different times) is to use a job sheet system. A job sheet is a form the client never sees but which is started as soon as any request for photography comes in. It follows the job around from shooting through printing to retouching and finishing, and finally reaches the invoicing person’s file when the completed work goes out. The job sheet also carries the job instructions, client’s name and telephone number. Each member of the team logs the time spent, expenses, materials, etc. in making their contribution. Even if you perform all tasks single-handed, running a job sheet system will prevent jobs being accepted and forgotten, or completed and never charged for.

Contracts

The agreement between photographer and client should be defined by a contract, which is a legally binding document. The negotiation of the contract is the process of deciding on fees, terms and conditions, and usage and copyright of images. It is important that both photographer and client are clear about the terms of the contract; if either side fails to fulfl their obligations then the other party may pursue them for compensation through the legal system. The aim, therefore, is to protect the interests of both parties. For this reason verbal agreements about a photographic assignment should always be followed up with something written down, even if by email; having something traceable prevents later misunderstandings. Photographers should obtain written confirmation of conversations, and include terms and conditions covering details of copyright, usage, third parties, cancellation, etc. (see below). Once all the terms have been agreed and written down by one party, they should be sent to the other party, to be signed and sent back. Both sides should keep a copy of the contract.

Often, publications such as newspapers or magazines will have their own standard contracts which they will expect you to work to. These may include how much they are prepared to pay and will undoubtedly include their terms and conditions. It is important to check exactly what is being offered before accepting a job from them, as by doing so you will be entering into a contract with them. Such contracts may or may not be negotiable; if you do negotiate, again you must ensure that you obtain the negotiated terms in writing.

Initial booking

In the beginning a booking will often be by phone or email contact, and it is at this point that you will obtain details of the images required. The client may provide a clear written briefng, or their requirements may need to be carefully defined in conversation with them. As well as the information about the images required, it is important to get clear agreement about the date, location, format and media, and some idea of how the images are to be used, i.e. if they are to be published and if so how many times and where. Written notes should be made of these initial conversations and it is helpful to keep them with the other documentation for the particular job, to be easily referred to if necessary. It is also at this point that fees should be negotiated. It may be that the client comes with a specific budget in mind, which the photographer may or may not accept. Alternatively, you may use the information gathered to specify the fee based on your day rate, or on a per image basis. Issues around copyright ownership and licensing must be clarifed at this stage, as they will have an impact on the fee charged. Cancellation fees should also be defined, if stylists, models, assistants, food stylists or locations are to be booked. You don’t want to be left with having to pay all these people if the job gets cancelled or delayed.

Confrmation

Once the details of the job and fee have been agreed, the next stage is to confirm them in writing, which might be done by email or more formally using a commissioning form, or commission estimate. The form should be designed so that it has spaces for subject and location, likely duration of shoot, agreed fee and agreed expenses. It also specifes what the picture(s) will be used for and any variations to normal copyright ownership. If using a commissioning form, your terms and conditions should also be included. Once signed by the client this will serve as a simple written contract. The form therefore avoids difficulties, misunderstandings and arguments at a later date – which is in everyone’s interests.

Terms and conditions

Your terms and conditions should be included on the majority of the paperwork that is sent out; it is common practice to print them on the back of all standard forms. The terms and conditions define the legal basis on which the work is being carried out; however, if the client includes a different set of terms and conditions on any paperwork they send to you, theirs may override yours, so this is something to keep in mind. Clients may choose to negotiate terms and conditions, particularly in terms of copyright and usage of images; if they do not then it may be assumed that your specified terms and conditions are accepted and they become a part of the contract between you and the client.

Terms and conditions allow you to be specific about how you will work; they spell out details such as cancellation fees, the extent of a ‘working day’ and so on. Importantly, they should include details of copyright, usage, client confdentiality, indemnity and attribution rights. Photographic associations will often have standard sets of terms and conditions for you to use; an example set for photographers in England and Wales produced by the Association of Photographers (UK) is reproduced in Figure 15.2.

Model release

Anyone who models for you for a commercial picture should be asked to sign a ‘model release’ form (see Figure 15.3). The form absolves you from later claims to influence uses of the picture. Clients usually insist that all recognizable people in advertising and promotional pictures have given signed releases – whether against a fee or just for a tip. The exceptions are press and documentary-type shots where the people shown form a natural, integral part of the scene and are not being used commercially.

After the shoot: sending work to the client

Once the shoot has been completed, what happens to the images will depend upon what you have agreed with the client. It will also be based on what type of media you work in, either film or digital. If you are using film, you may well need to send the originals to the client, unless they only want prints. The risks in terms of loss of originals are obviously greater with film, as digital images allow you to keep archived originals as well as sending them out. It is therefore important that you make sure that images are insured while in transit. Often, clients will want printed contact sheets even if you are working digitally and this can be an opportunity to make a selection of the better images and present them in an attractive manner. If producing film originals, the client may want digitized versions as well. Offering image scanning as an additional service can be an extra source of income, whether you have time to do this yourself or choose to get them scanned by a lab. For news images, it is possible that you will be sending the finished images over the Internet. It is important in this case that you ensure that the images are saved to the correct image dimensions, resolution and file format for the client. The way in which you present your work, whether transparencies, film, contact sheets or digital images, is important; although they may not be the finished product, it helps to make you appear more professional, which can be important in marketing yourself and obtaining more work. An example of a selection sent out to a client is shown in Figure 15.4. It is important to have a client area on your website where you can post images for specific jobs. Each client will have a job-sensitive area where they can log in and see their images for selection and approval.

However you send your images, whether electronically or as hard copies, it is vital that you protect yourself against loss or damage to the images and also against clients using them without your permission. To do this you need to include a delivery note whenever you send images to another party, which can be either digital or hard copy. It should include details of the client’s name, address, contact name and phone number/email, method of delivery, date of return and details of fees for lost or damaged images. The number, type and specifics of the images should be described. Terms and conditions should be printed on the reverse and this clearly stated on the front of the note. It should have a unique number to allow you to track and file it. You should also have a specific statement regarding your policy about the storage or

Terms and conditions

1. Definitions

For the purpose of this agreement ‘the Agency’ and ‘the Advertiser’ shall where the context so admits include their respective assignees, sub-licensees and successors in title. In cases where the Photographer’s client is a direct client (i.e. with no agency or intermediary), all references in this agreement to both ‘the Agency’ and ‘the Advertiser’ shall be interpreted as references to the Photographer’s client. ‘Photographs’ means all photographic material furnished by the Photographer, whether transparencies, negatives, prints or any other type of physical or electronic material.

2. Copyright

The entire copyright in the Photographs is retained by the Photographer at all times throughout the world.

3. Ownership of materials

Title to all Photographs remains the property of the Photographer. When the Licence to Use the material has expired the Photographs must be returned to the Photographer in good condition within 30 days.

4. Use

The Licence to Use comes into effect from the date of payment of the relevant invoice(s). No use may be made of the Photographs before payment in full of the relevant invoice(s) without the Photographer’s express permission. Any permission which may be given for prior use will automatically be revoked if full payment is not made by the due date or if the Agency is put into receivership or liquidation. The Licence only applies to the advertiser and product as stated on the front of the form and its benefit shall not be assigned to any third party without the Photographer’s permission. Accordingly, even where any form of ‘all media’ Licence is granted, the photographer’s permission must be obtained before any use of the Photographs for other purposes e.g. use in relation to another product or sublicensing through a photolibrary. Permission to use the Photographs for purposes outside the terms of the Licence will normally be granted upon payment of a further fee, which must be mutually agreed (and paid in full) before such further use. Unless otherwise agreed in writing, all further Licences in respect of the Photographs will be subject to these terms and conditions.

5. Exclusivity

The Agency and Advertiser will be authorised to publish the Photographs to the exclusion of all other persons including the Photographer. However, the Photographer retains the right in all cases to use the Photographs in any manner at any time and in any part of the world for the purposes of advertising or otherwise promoting his/her work. After the exclusivity period indicated in the Licence to Use the Photographer shall be entitled to use the Photographs for any purposes.

6. Client confidentiality

The photographer will keep confidential and will not disclose to any third parties or make use of material or information communicated to him/her in confidence for the purposes of the photography, save as may be reasonably necessary to enable the Photographer to carry out his/her obligations in relation to the commission.

7. Indemnity

The Photographer agrees to indemnify the Agency and the Advertiser against all expenses, damages, claims and legal costs arising out of any failure by the Photographer to obtain any clearances for which he/she was responsible in respect of third party copyright works, trade marks, designs or other intellectual property. The Photographer shall only be responsible for obtaining such clearances if this has been expressly agreed before the shoot. In all other cases the Agency shall be responsible for obtaining such clearances and will indemnify the Photographer against all expenses, damages, claims and legal costs arising out of any failure to obtain such clearances.

8. Payment

Payment by the Agency will be expected for the commissioned work within 30 days of the issue of the relevant invoice. If the invoice is not paid, in full, within 30 days The Photographer reserves the right to charge interest at the rate prescribed by the Late Payment of Commercial Debt (Interest) Act 1998 from the date payment was due until the date payment is made.

9. Expenses

Where extra expenses or time are incurred by the Photographer as a result of alterations to the original brief by the Agency or the Advertiser, or otherwise at their request, the Agency shall give approval to and be liable to pay such extra expenses or fees at the Photographer’s normal rate to the Photographer in addition to the expenses shown overleaf as having been agreed or estimated.

10. Rejection

Unless a rejection fee has been agreed in advance, there is no right to reject on the basis of style or composition.

11. Cancellation & postponement

A booking is considered firm as from the date of confirmation and accordingly the Photographer will, at his/her discretion, charge a fee for cancellation or postponement.

12. Right to a credit

If the box on the estimate and the licence marked ‘Right to a Credit’ has been ticked the Photographer’s name will be printed on or in reasonable proximity to all published reproductions of the Photograph(s). By ticking the box overleaf the Photographer also asserts his/her statutory right to be identified in the circumstances set out in Sections 77–79 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or any amendment or re-enactment thereof.

13. Electronic storage

Save for the purposes of reproduction for the licensed use(s), the Photographs may not be stored in any form of electronic medium without the written permission of the Photographer. Manipulation of the image or use of only a portion of the image may only take place with the permission of the Photographer.

14. Applicable law

This agreement shall be governed by the laws of England & Wales.

15. Variation

These Terms and Conditions shall not be varied except by agreement in writing.

Note: For more information on the commissioning of photography refer to Beyond the Lens produced by the AOP.

Figure 15.2 Standard set of terms and conditions for photographers in England and Wales. © Association of Photographers. This form is reproduced courtesy of the AOP (UK), from Beyond the Lens, 3rd edition (www.the-aop.org).

Figure 15.3 Example of a Standard Model Release Form. © Association of Photographers. This form is reproduced courtesy of the AOP (UK), from Beyond the Lens, 3rd edition (www.the-aop.org).

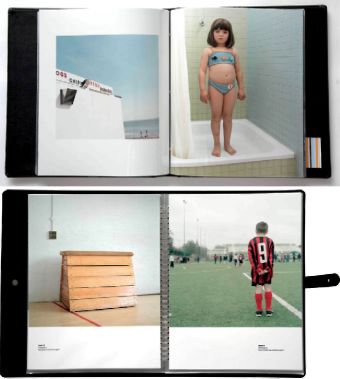

Figure 15.4 The way in which originals and contact sheets are presented to a client is important. Attractive presentation may help in both selling the images and obtaining further work from the client, and may be used as part of your self-promotion. Image© Ulrike Leyens (www.leyens.com).

reproduction of the images without your permission. By accepting the images with the delivery note, the client is agreeing to these terms.

Copyright

Be on your guard against agreements and contracts for particular jobs which take away from you the copyright of the resulting pictures. This is important when it comes to reprints, further use fees and general control over whom else may use a picture. If an agreement permanently deprives you of potential extra sources of revenue – by surrender of transparency or negative, for example – this should be reflected by an increased fee. Generally, in most countries around the world, copyright automatically belongs to the author of a piece of work, unless some written agreement states otherwise; therefore, you will retain ownership unless you choose to relinquish it. By including your terms and conditions with all documentation and having a written contract, you are protecting your copyright. As owner of the copyright of the image, you may choose what you do with it and you can prevent others from reproducing it without your permission.

You can assign your copyright to someone else – in other words, you choose to give it up or sell it. What this means is that you will no longer have any rights to the image, any control over how it is used and, most importantly, you will no longer be able to make any money from it. Bearing in mind that your back catalogue of images can potentially be an ongoing source of income it is not wise to ever give up your copyright unless you have very good reason to.

It is much more common, however, to retain copyright and agree usage of the image. This is in the form of a licence, which defines the reproduction rights of the client based on what they have paid you. The licence will specify, among other things: type of media, e.g. printed page, web page, all of Internet; length of time that the client may use the image; quantity of reproductions (this may be approximate, but is generally an indicator of circulation); number of reproduced editions; territory (this specifes the geographical area that it may be published in, for example Europe only or worldwide use). The licence may be exclusive, meaning that, for its duration, you may not sell the image on to anyone else and no other party may use it. It protects the interests of the client and allows them to take legal action if anyone else infringes the copyright during this period. This is quite common in press photography in particular. Once the duration of the licence has ended, the client may no longer use it. If the licence was exclusive, then at the end of its duration you will be free to sell the image on. You may choose to syndicate your image, in other words sell it on to multiple magazines or newspapers, which can be very lucrative. The client may, however, negotiate an extension or a further licence and will again pay a fee for this. Before this you may continue to use it for self-promotion, in your portfolio or on your website, but will be restricted from using it elsewhere.

There are some cases where you will have no choice but to give up your copyright, for example if you are working as a staff photographer, where it is specified in your contract of employment. Some of the large news agencies, such as Reuters or the Associated Press, have also introduced contracts where they own the copyright of images and you are just paid a day rate. If they choose to use your images more than once, it may be possible to negotiate a deal for further fees.

Digital rights

Digital imaging has made enforcement of copyright more difficult, as images are much more widely distributed and it is simple to make copies of digital images, download them and store them on a computer. It is also easy to alter digital images with image-processing software. Both are infiringements of the image copyright. You should ensure that your images on the web carry copyright information, and that it is easily visible. You may also choose to use some form of watermarking or image security software. This may involve simply embedding copyright information in the image, which will be visible if the image is downloaded. However, many watermarks can be removed; it may be something more sophisticated, which prevents the user from copying or altering the image and identifes if an image has been tampered with. The issue around image altering is an important one too. It is surprising how many people working in the imaging industries are unaware that this is copyright infiringement. It is quite common to find that an image submitted to a news desk by the photographer is subsequently published with significant alterations without permission. This cannot be prevented, but you can protect yourself legally by including a clear copyright statement about reproduction, making copies and altering of the image whenever you send the image to anyone.

Marketing your business

Like any other service industry, professional photography needs energetic marketing if it is to survive and fourish. The kind of sales promotion you need to use for a photographic business which has no direct dealings with the public naturally differs from one which must compete in the open marketplace. However, there are important common features to bear in mind too.

Your premises need to give the right impression to a potential client. The studio may be an old warehouse or a high-street shop, but its appearance should suggest liveliness and imagination, not indifference, decay or ineffciency. Decor and furnishings are important, and should refect the style of your business. Keep the place clean. Use equipment which looks professional and reliable.

Remember that you yourself need to project energy, enthusiasm, interest, skill and reliability. Take similar care with anyone you hire as your assistant. On location arrive on time, in professional-looking transport containing efficiently packed equipment. Dress appropriately for the job and client, and ensure that all crew members do the same; they are your employees, if only for a day, and should refect your business. If you want to be an eccentric this will ensure you are remembered short term, but your work has to be that much better to survive such an indulgence. Most clients are arch conservatives at heart. It is a sounder policy to be remembered for the quality of your pictures rather than for theatrical thrills thrown in while performing.

During shooting give the impression that you know what you are about. Vital accessories left behind, excessive fddling with meters, equipment failures and a feeling of tension (quickly communicated to others) give any assignment a kiss of death. Good preparation plus experience and confdence in your equipment should permit a relaxed but competent approach. In the same way, by adopting a frm and fair attitude when quoting your charges you will imply that these have been established with care and that incidentally you are not a person who is open to pressure. If fees are logically based on the cost of doing the job, discounts are clearly only possible if short cuts can be made to your method of working.

The methods that you use to market your work and the way in which it is presented will depend upon your field. But whatever area you work in, you will undoubtedly need a portfolio. In some cases this may be the only opportunity to make an impression on a potential client, as you may be asked in some cases to leave your book with them and never get the chance to meet them face to face. The images in your portfolio of course need to be relevant to the field you are working in, both stylistically and in substance. It is also possible that you will need to change them to suit the interests of different clients.

The content therefore needs to be carefully thought out and put together. The images must be selected with care; they should be your best pieces of work and effectively represent the range of your skills and abilities. You should not include everything: avoid duplication and streamline where possible; a smaller, more concise portfolio appears more professional than one that contains every piece of work that you have done. It is also important that you include some recent work. You should review your portfolio(s) every few months and update where necessary.

You should aim for some sort of consistency in your images – for example, grouping them according to type or content. They will look better if all presented in the same way wherever possible, on the same type of paper, similar dimensions and the same method of mounting. Paramount of course is the quality of the prints. It can be extremely useful to look at other people’s portfolios to get an idea of different styles of presentation. Figure 15.5 shows some examples.

It is also useful to include examples of work that has been published – for example, ‘tear sheets’ and page layouts from magazines that include your images. Ask your clients for extra copies for your portfolio. If you have the opportunity to meet with clients then you should make sure that you talk them through your images; this is a good chance to put your ideas and your enthusiasm across.

If you are going to leave your portfolio with a client, include a delivery note; the same rules apply as for sending images, in terms of protecting yourself against loss or damage to

Figure 15.5 Presentation in portfolios. Images © Ulrike Leyens (www.leyens.com) and Andre Pinkowski (www.onimage.co.uk).

Figure 15.6 Postcards and business cards can be useful marketing tools. Image © Ulrike Leyens (www.leyens.com).

your images. You may want to include other material as well, particularly if you are not able to actually meet with the client. Giving them something they can take away with them will help to remind them of you and your work; even if they do not choose to use you at this point, they may do so in the future. This may be a short CV or covering letter along with a business card.

Figure 15.7 Families brave the cold temperatures and snowy conditions on top of the South Downs at Clayton in Sussex. Jack and Jill windmills are seen in the background. Image included in the Press Photographers Year Awards 2006. © James Boardman Press Photography (www.boardmanpix.com).

The business name, logo, notepaper and packaging design, along with all your printed matter, should have a coherent house style. Better still, get a booklet or some postcards (promo cards) with your images, logo and web address printed, and include these (see Figure 15.6). They can also be useful to send out to previous clients. It is good practice to keep in touch after you have worked for someone, and sending the client emails or printed material with examples of new images or information about shows and exhibitions that you are involved in is a useful way to remind them of your work.

Entering photographic competitions is another way to get your work seen and capture the attention of picture editors in particular. Professional competitions such as Press Association Awards (see Figure 15.7), for example, will be attended by the people buying the images. Often, entries will be placed in an exhibition and in an associated book, even if they do not win an award, giving you free publicity and the opportunity to get your images seen by the people that count. The private views for these types of competitions are high-profile events and a good chance to network.

As well as the other benefits that membership of professional societies and associations offer, they may be able to help to publicize your work. Most have related publications in which they showcase member’s work. They also often have sections for members’ portfolios on their websites.

Of course, the widespread use of computers and the Internet mean that a website is a vital marketing tool. It can be easy to direct someone to your work and include your URL on every email, meaning that you reach a much wider audience without the labour involved in booking appointments and carting round a portfolio. Additionally, you may present your work electronically on removable media, such as a DVD or USB drive (also called a ‘thumb drive’ or ‘key drive’). These can be a clever way to get your work to clients, particularly if you have your studio or company name and logo printed on the disk or drive. However, this should not be considered a replacement for a portfolio; many people prefer to sit down and browse through high-quality and nicely presented prints rather than look at them on a computer screen.

You may choose to pay someone to design your website for you; however, there are a number of software applications that make it relatively easy for you to create one yourself if you are prepared to learn how. Similar rules apply in terms of selection and presentation of images as for your portfolio, although you may choose to include more images on a website (see page 378). Because websites are interactive and inherently non-linear, it can be useful to group your images in different galleries and therefore you have an opportunity to present much more work, although again you must make sure that they represent the best of your work. You will also have an opportunity to include a short CV and information about yourself. You may even use the site to sell images. Bear in mind the issues around copyright: include copyright statements clearly throughout and give some consideration to image security and watermarking.

SUMMARY

- Unless you choose to work as a photographer employed by an organization, being successful in a career in photography involves an understanding of a number of aspects of business practice, including bookkeeping, insurance, contracts, the nature of commissioning, general administrative systems and self-promotion.

- Although you may use an accountant for end-of-year tax returns, you will need a number of systems to keep track of the fnancial aspects of your business, including invoices, expenses, purchasing, petty cash and the depreciation of equipment.

- You will need to make sure that you have insurance to cater for the needs and size of your business. At the least you should have equipment insurance and if you have anyone working for you, paid or unpaid, you will need Employer’s Liability insurance, or the equivalent. Other useful insurance includes Public Liability insurance and Professional Indemnity insurance.

- When deciding what to charge for a job, it will usually be based upon your day rate. In some cases the client may specify a day rate; otherwise your day rate should be calculated to take into account business overheads and your salary. Also included in the fee will be expenses directly associated with a particular shoot.

- You will need to track the progress of individual jobs and expenses, and ensure that you have a consistent process for invoicing and chasing payment. To do this you will need a good system of paperwork, which should include the terms and conditions for an individual contract. This ensures that you cover yourself and can take legal action for non-payment.

- Your terms and conditions define the legal basis for work to be undertaken. They will be negotiable before a contract is agreed. You must ensure that both parties are clear about the terms and conditions for a particular job, as clients’ terms and conditions can override the photographer’s. All changes should be confirmed in writing.

- A model release form should be used when photographing people, other than in certain documentary or press shots where the people are a natural part of the scene. This is particularly important when photographing minors.

- Copyright is important in protecting your interests and ensuring that your images are not used without your permission.

- Copyright, in most cases, automatically belongs to the photographer (unless working as a staff photographer or for some news agencies). You should avoid giving up or assigning your copyright wherever possible, as this means that you will no longer have any control over the image and cannot make money from it.

- You may instead license your images, which allows a client to use the images under specific conditions and for a particular duration. Clients may ask for an exclusive licence for that period. They may also negotiate further licences once one has expired.

- Copyright is more complicated when referring to digital images. The storage of copies of digital images and the altering of digital images constitutes copyright infiringement.

- Self-promotion is vital to the success of your business. Care must be given to the way in which you present yourself, your premises and your work. A portfolio is an important opportunity to present your work and should be carefully compiled. A website is also a necessary marketing tool.