Chapter 9

The Intersection of Culture and Ethics

Objective

This chapter discusses how culture affects ethical and moral standards; this phenomenon, then, requires coaches to expand their personal approaches to coaching people of different cultures. We examine the interaction of cultural differences and ethics in coaching, and the effects of this interaction on coaching cross-culturally. We propose that no one ethic pervades all cultures, and that it is the coach’s responsibility to discern nonjudgmentally those situations, attitudes, and behaviors that reflect ethical dilemmas. We discuss frameworks for understanding cultural values, and how those values drive ethics, and we make distinctions between cultural and individual values in coaching. A key consideration is who will do how much adjusting (client/coach, host/visiting culture, etc.) when it comes to intercultural variances, including ethics.

Pre-Chapter Self-Assessment Test

Answer on a scale of one (1) to five (5), with one (1) being strongly disagree and five (5) being strongly agree:

Introduction

Culture is the galaxy of unique shared beliefs, values, communication styles, and behaviors that differentiate one group from another. Sources of a group’s culture include the land upon which the group members live, their history, their family models, and their socioeconomic and political environments. As humans, we learn from these environments to behave in certain ways, and we often judge the world by what is familiar.

The effects of culture are that we all experience discrimination and stereotypes, but money and power can buffer us from the effects of discrimination. The outcomes of culture are that we tend to seek the company of those most familiar to ourselves, and we resist change and the unfamiliar. As Edward W. Said remarked in Culture and Resistance, “Culture is a way of fighting against extinction and obliteration” (2002).

When coaching someone from a different culture, coaches may unknowingly engage in inappropriate behavior unless they are culturally aware. To be culturally aware means not only to become familiar with clients personally and professionally, but also with their culture. It also means coaches must be aware of their own culture, the potential differences between their culture and that of their clients, and how those differences might have an ethical impact upon the coaching relationship.

Even within one country, cultural diversity exists. Cultural groupings occur through geography (nation, region), profession, gender, religion, social system (social class, family, organization, ethnicity), and physical ability. Businesses, governments, and societies are sometimes governed by diverse and ambiguous rules of conduct. As coaches, we interrelate with people who face dilemmas daily as a result of these ambiguities, and we have a responsibility to create an environment in which these individuals can access behaviors and attitudes that will work and are appropriate for the culture. For example, persuasion in the United States is often considered strength, but in Japan is considered rude. There are also differences in corporate culture as to the amount of persuasion that is acceptable. As coaches we meet people who have to manage in such environments and may not understand how to do so. We must create an environment in which they can understand that there are differences, and that to be effective they need to adapt.

Ethics and morals are often cited as what determine the appropriateness of an action; however, ethics and morals mean different things for different people. For ethics, philosophers explore concepts, dilemmas, and theories of good;while most of us, knowingly or otherwise, establish or define operational standards for proper, fair behavior when dealing with others.

Morals are often described as a set of rules that govern behaviors considered to be good by the majority of rational members of a given society. The rub is that moral standards covering all behaviors vary depending upon the society or situation. Bribery is often cited as an example of the culturally dependent nature of moral standards because bribery is considered illegal in many cultures, but is viewed in others as a legitimate commission for participating in a business transaction. As discussed later, this view of bribery as legitimate has ethical limitations.

A more mundane, but relevant, example of the variability among moral standards involves stopping at a red light late at night. In China, for example, one most likely would go through the light, based on a value system that rewards pragmatism—whatever works. In the United States, one might stop or go, depending upon the individual’s personal sense of balance between risk-taking and what is considered fair. No harm, no foul. In Japan, one might wait for the light to change, with the decision not dependent upon fear of breaking a rule, but rather upon consideration about being shamed, even by someone unknown to the individual. In Germany, one is likely to obey the red light signal and stop, simply because to do so is a rule.

Ethics may take multiple forms. Consider ethics based upon principles. Principles are supposedly indisputable and not to be compromised. No individual personal judgments about good-bad-right-wrong are considered valid. Common examples of principles might be to not lie or steal; or following the maxim, “The ends do not justify the means.” On lying and stealing, Mark Twain once said, “If opportunity and desire came at the same time, who would escape the gallows?” Telling white lies or taking a few paper clips home from work does not necessarily make us unethical persons, and a white lie may be for a greater good. On the question of the ends justifying the means, there are tremendous variations in the weight ascribed by various cultures to this principle. To the Chinese, pragmatism is a core value—it does not matter whether the cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice. To an American, it is how you play the game, although recent corporate malfeasance and sports drug scandals seem to undermine this maxim. Unfortunately, applying the concept of principled ethics often avoids dilemmas instead of resolving them. We explore this issue interculturally later in the chapter.

Another form of ethics goes beyond relying on principles. Based upon respect for humanity, this type recognizes that dilemmas exist in the real world. This form, sometimes termed applied ethics, relies on appropriate individual judgment, encourages personal responsibility, seeks awareness of applicable moral standards, and stresses compliance with these components. This form allows for deviation from principled ethics when such deviation is for the legitimate benefit of others—for the benefit of humankind.

Applied ethics is not to be confused with situational ethics: “This is the way we do it here.” In situational ethics, each person decides what seems to be the right thing to do, without reference to the moral standards of the majority. Situational ethics allows almost anything.

Ethical behavior is not always expressly mandated in workplaces, given the evidence, although the authors have reviewed many corporate ethical guidelines translated into multiple languages. Implicit guidelines, however, are unsatisfactory, particularly with respect to collective and corporate actions. Often, the responsibility for ethical behavior is somehow assumed to belong to the boss; however, this responsibility must be resident at all levels in the organization for effectiveness.

The Interaction between Culture and Ethics: The Cultural Iceberg

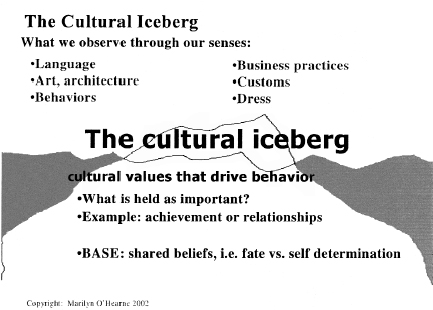

If you have studied Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, you remember the iceberg effect as applied to the conscious/unconscious mind. What we are conscious of is just the tip of the iceberg. And so in cultures: what we can observe through our senses—behaviors, language, dress, art, customs—is the tip of the iceberg (see Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 The Cultural Iceberg

Below the surface are the cultural values that drive the behaviors. Values are what people hold to be important. In some cultures, a value might be achievement; in others, relationships. The values a culture holds will affect what behaviors are appropriate (ethical) and acted upon.

The base of the iceberg represents a culture’s shared beliefs. A culture that believes in fate or luck will have different values and behaviors from a culture that believes people determine the direction of their lives through their choices.

As coaches, we join with our clients in identifying their personal values, which say something about who they are as an individual. Cultural values relate to who we are as members of a cultural group; a norm or standard of what is considered ethically right. Individual values represent what individuals desire;cultural values, what the group desires.

To be effective coaching interculturally, we need to understand and, especially with teams, to integrate and leverage cultural differences. But where do we draw the ethical line? Who does the adjusting, how much, and when? For example, while teaching an Organizational Behavior and International Business course in Hong Kong and Malaysia, students’ answers to discussion questions on preferred management practices were different from the U.S. textbook’s answers because the students’ culture is more collective than individualistic. The Hong Kong/Malaysia culture emphasizes “we”—what is good for the group—rather than “I”—what is good for me. What may be seen as good and ethical business practices in one culture may not be considered so in another. It is the coach’s responsibility to take the initiative to understand, note, and articulate differences.

The Relevance of Coaching to Culture and Ethics

Basic principles of coaching lend themselves well to intercultural environments. First, the highly personalized process of coaching supports the infinite range of possible situations in which persons might find themselves. Next, the process is specifically designed to bring about learning, effective action, and performance improvement, which then leads to personal growth for the individual, as well as better business results for the organization.

Coaching is specifically designed to build the person’s level of awareness and personal responsibility for actions and behaviors, while providing structure and feedback in a collaborative process between the coach and key players within the organization. This involvement, while maintaining confidentiality, unleashes the individual’s potential to meet personal and organizational goals and objectives.

Organizations tend to choose employees who learn best from new experiences and place them in multicultural settings. These new environments might include international work, overseas assignments, and multicountry alliances. In the throes of being in a new environment, employees are also possibly dealing with negotiations, culture shock, and how to manage diversity. Research seems to suggest that learning in a different culture occurs best when certain strategies are in place for the learner. These strategies include listening well, communicating openly and clearly, solving problems, and accepting responsibility for one’s own behavior while exploring new environments.

As a coach adjusts to a new culture (because of the assignment) or helps a client adjust to a new culture, it is helpful to remember that learning moves in two directions:

Coaches can remind themselves and help their clients to recognize that intercultural competencies motivate people to break out of their own cultural mind-sets and begin exploring new cultures and those cultures’ social customs and systems. For example, having intercultural communication competencies also enables people to work together to solve common problems and achieve organizational objectives.

As a point of clarification, integrating into another culture is not abandoning one’s own ideas and values in exchange for wholly absorbing or accepting those of another culture (just as it is not prudent to leave your own toothbrush and comb at home on a trip, and expect to use those of the host where you stay). Rather, integrating into another culture means critiquing one’s own cultural values and norms, learning and critiquing the norms and values of another culture, transcending one’s own culture, and then internalizing appropriately those valued perspectives one has gained from a different culture. This process goes beyond integration and actually provides for the possibility of personal transformation.

Bringing Ethics into the Coaching Environment

As mentioned previously, ethics is a method of determining right and wrong, and morality is a system of practices that produce conformity of behavior within a community. Many cultures believe the individual is primary, and so ethics supersede morality. Other, more communitarian, cultures believe a system of morality is critical to cultural survival.

In addition, theories of morality or ethics state that we have the duty to bring about the greatest good overall, and that we are required not to deceive others with whom we have social partnerships. An example of operating from the belief that one has a moral and ethical duty to bring about the greatest good overall would be a situation in which a person comes in to his manager and states that his wife has a serious illness, but the HR policies do not cover the expense of medicines that would cure her. The question to the coach would be how to motivate the client to explore possibilities that would solve the dilemma of deciding between aiding one person and adhering to policies that reflect the common good. An example that represents the moral/ethical requirement not to deceive others is that of corporate governance and transparency, which we explore next.

Governance

Governance, transparency, and leadership are each spokes of the rudder that steers organizations through legal, ethical, and moral opportunists who seem to be waiting at every corner. Governance is the process by which an organization or society conducts its behavior, both internal and public. Transparency is about involvement. It means to communicate in such a way that stakeholders in what you are doing (corporate or otherwise) are involved. Leadership has many definitions: the one we are referring to is the ability of people to create an environment in which they can create their own (and the company’s) destiny. Develop one of the three, and you will likely achieve the other two. Governance is internal, in that it defines the manner in which power and creativity are used within the organization. It is to this end that coaching most benefits the organization: shaping the individual’s response to the ever-changing environment.

Governance has many faces throughout the globe. For example, in the United States, governance is upheld through complex balances between government regulation and shareholder power. In Japan, though, the complex systems of relationship and obligation, consensus building, and peer review provide a form of governance that from the outside might seem cumbersome and sluggish. Some Japanese companies have changed to more effective governance systems; but cultural internal processes remain largely intact. Chinese companies depend heavily on relationships to provide governance; however, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and in this culture shared ownership, the board, and management often work against the levels of transparency needed to provide confidence to the outside investor.

As leadership and governance models become more horizontal, power is shared with others throughout the organization, which requires higher levels of cooperation and transparency. In periods of change, and in intercultural settings as companies decentralize, people are often reluctant to give up power. In many cultures, coaching can play a strategic role in the development of leaders that foster the required transparency and cooperation in decentralized multicultural organizations. The coach can support leadership transformation by working with individuals to expand competencies of empathy, openness, tolerance, and flexibility.

The Legal Environment

The U.S Congress enacted the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) in 1977 after Securities and Exchange Commission investigations during the mid-1970s revealed that more than 400 companies had paid questionable or illegal payments in excess of $300 million to foreign government officials and politicians. Under the law, executives can go to jail, and companies can be fined and barred from government procurement contracts, for infractions of the law.

To avoid legal consequences, many firms have implemented detailed compliance programs intended to detect and prevent any improper payments by employees and agents, and to reflect accurately the transactions of the corporation through internal accounting controls. Most large global companies stipulate zero-tolerance toward infractions relating to the FCPA.

Although Congress originally enacted the FCPA to restore public confidence in the integrity of the American business system, Congress became concerned that American companies were operating at a disadvantage compared to foreign companies who routinely paid bribes. For example, in one discussion between executives of German and American companies operating in China, the German executive said, “We do not have to follow the same rules that you [the American company] do, so we will always win.”

Accordingly, the United States commenced negotiations in the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to obtain the agreement of trading partners to enact legislation similar to the FCPA. Ten years later, 34 countries signed the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions. Later, 43 countries signed the Anti-Corruption Convention, with Article 16 regarding bribing foreign government officials or public officials as a crime, with supporting jurisdiction, legal cooperation, and extradition provisions.

One example of the consequences of such agreements occurred in April 2004, when Lucent Technologies Inc. fired four executives at its Chinese operations, including the president, the chief operating officer, a marketing executive, and a finance manager, for violations of the FCPA, the company said in a filing with the U.S. SEC.1 An analyst with an investment bank told Caijing:

You have to get into the market to start businesses before everything is okay, and you have to adapt yourself to all kinds of “rules” . . . If the FCPA is strictly applied, 100 percent . . . have violated the law, whether they are American or European.

Lucent also said it uncovered problems in its operations in 23 foreign countries, including Brazil, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Russia, among others. What is interesting is that when reporting the story, Reuters quoted a risk-management expert as saying many multinational companies believe that corruption is “part of the culture and part of society” in China.

As discussed, culture evolves with history, mediated in the immediate by politics and the integration of new ideas. Although corruption often corrodes certain aspects of society as the result of social pressures, seldom does corruption become part of the widely accepted social culture. What does surface is a phenomenon that sociologists call social corruption. For example, in some countries, hospitals or physicians might prescribe unnecessary medicines to receive gratuities from pharmaceutical companies. In many countries, close relationships are obligatory to conducting business; however, there is a Chinese saying that a mare doesn’t run on an empty stomach. This implies that, from the course of business, some benefit always results.

The aphorism “Everybody does it” does not hold up to scrutiny, and experience demonstrates that business can be conducted cleanly and honestly. In working with developing leaders, coaches have the opportunity to bring out the best in their clients.

Ethical Checklist

The concept of business ethics has come to generally mean determining what is right or wrong in the organization, and then doing what is right. This concept is fraught with difficulty;some assert there is always a right thing to do based on moral principle, and others believe the right action depends upon the situation. Often, to alleviate this basic dilemma, we convert what we consider ethical today into a law, regulation, or rule tomorrow.

Another way to approach minimizing the possibility of ethical dilemmas and resolving them in an ethical manner is to use an ethical checklist, such as this one:

Co-created Cultures

Although these evaluations may be of assistance in the initial stages when a person is integrating into a new culture, such tests might lead to one of many popular myths, such as the following:

- Ethics only restates the obvious, so just do the right thing.

- It is obvious that honesty is important, but if a company has continuing occasions of corruption, it should list honesty as a value in the company code of ethics.

- Codes of ethics should change with the needs of society and the organization.

- Our organization is not in trouble with the law; therefore, we are being ethical.

- Western science, economics, and politics are universal.

Given the multiplicity of cultures and the concomitant array of ways to view ethics, the challenge becomes how to find unanimity as people bridge cultures. One culture’s value systems, morality, science, and politics are not universal; rather, they describe thought processes and behaviors particular to that culture. Even though one culture’s mores or sciences may be embraced by another, this is not assurance that the transference is collective or universal in nature.

The goal of the coach in intercultural settings is to motivate individual behaviors and facilitate human interactions. A culturally aware coach can catalyze a neutral zone that bridges the gaps between the cultures, instead of forcing everyone to act in the same way. In addition, the coach can stimulate the client to:

- Explore ways to define the mutual space to involve others, such that all parties can contribute.

- Recognize and understand cultural diversity, personal accountability, and the power to change.

- Induce the formation of a third culture, or space in which people evolve new ways of accomplishing tasks.

- Constructively assess the behaviors of the other culture, and possibly transform those behaviors.

Co-creating cultures can happen on the business level as well as the personal level. For example, a company expands operations into East Asia (Japan, Korea, and China) and decides to use Asian social processes (relationships, expectations, harmony, and reciprocity) along with Western business processes (disciplined communication channels, responsibility and accountability, business ethics). On a personal level, some of the employees of this company will bring their home culture with them, or try to find it in the new host culture. Sometimes, this approach equates to a convoy mentality in which the persons enter the host culture together only with others sympathetic with the home culture. Other employees will enter this new culture immediately and encompass the host culture in its entirety. Still others will learn to balance host and home cultures by maintaining vestiges of their home culture that are supportive, and integrating those aspects of the host culture that feel comfortable.

The culturally aware coach chooses not to judge the process of the sojourner, but rather to motivate the client to search for new possibilities. For example, I (Charles) coached an American who had been living in Tokyo for two years. One particular evening as we left the office at the end of the session, my client seemed concerned that his wife had the car because he had never ridden the Tokyo subway. Here was an opportunity as coach to help this client see that riding the subway gave him the opportunity to venture out into places that driving would never have taken him.

In another instance, a young Indian couple was adjusting quite well to their new Melbourne home; however, during our conversations, the female partner remarked that she had been gaining weight just staying in the house all day. In India, women’s routines of family life often are led from meal to meal, preparing and conversing with family and friends. Because she had no friends or family, she was totally engrossed in an unfamiliar world without the benefits of either culture. As a coach, one of my objectives was to stimulate actions in which she could both venture out into the Melbourne world and maintain the traditional value of a home-cooked Indian meal, ready when her husband returned from work.

Co-creating a culture with family members, colleagues, and friends is a strategy that allows freedom to balance those aspects of life that mean the most to the people who are moving into a new culture. The coach has a responsibility to encourage the development of strategies that lead not just to integrating within the community, but also to personal transformation.

Best Practices and Considerations for Coaching Ethically across Cultures

The world environment is in constant change, with countries recreating themselves along cultural and ethnic borders, workforces increasing their diversity, competition intensifying trade relations, and technology outpacing yesterday’s innovators and innovations. Within this mélange of disparate and often conflicting pressures, the individual searches for ways to lead colleagues, develop leadership in others, thrive during cultural transitions, and live a more balanced and rewarding life. In support of the coach’s mandate to create strategies that meet these demands, we offer the following considerations within the framework of the International Coach Federation (ICF) Coaching Competencies and Code of Ethics (http://www.coachfederation.org/eweb/).

- We encourage you to not assume that commonalities exist between you and your clients, or between your clients and their partners or staff. Be self-aware, taking your beliefs into account in your approach to coaching clients. Be aware of your clients’ culture and how that shapes their mind-set and practices, including their approach to coaching (what is appropriate, what is ethical, and what is not). Recognize that there might be many cultural groups within a country. China, for example, has more than 50 nationalities, nearly as many languages, and at least five major cuisines. This reality ties into the ICF’s first two coaching competencies, which address meeting ethical guidelines and establishing the coaching agreement.

- Remember to evaluate and interpret situations from a multicultural frame of reference; for example, different approaches to time. For instance, the Latin cultures in which Marilyn has lived, and the Bahamas, where she has traveled, have a different sense of time than U.S. cultures. A client from another culture may say he will complete his fieldwork, action plan, or goal by a certain date, and then does not. A culturally aware coach will check to see whether this missed deadline has to do with the client’s cultural orientation to time, or whether something else is getting in the way. If a client from another culture runs late for appointments, a review of the coaching policy is appropriate, or the coach can explore cultural differences with the client, and they can implement a mutual plan to meet the needs of each person. The choice gets back to who does the adjusting, when, and how much, which is a common thread in intercultural work.

- Ethical considerations in the multicultural coaching agreement include confidentiality. How far will you take confidentiality if a client discloses illegal, or what you would consider unethical, behavior? Will you specify confidentiality limits in a written agreement at the beginning of coaching, or wait and see whether the issue comes up? If you are working within an organization, would you have to report this situation to someone in the organization? To the legal authorities? Note: “Know the law” can be very challenging when laws vary from state to state, as well as from country to country.

- Know the difference and importance of high-context culture and low-context culture. For example, in a high-context culture (such as Asia, Latin America, Southern Europe), nonverbal, indirect communication is important, with the physical context relied upon for information; whereas, in a low-context culture (such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Northern and Central Europe), the communication is direct and less dependent on nonverbal cues and the environment. How will this difference affect how you formulate your coaching agreement? Will you meet in person, on the phone, or by email? How much do you put in writing, and how much should be verbal agreement?

- Gaining clarity regarding the distinctions between counseling, coaching, and consulting may be more challenging interculturally. Also, making a referral for counseling in a culture where saving face is important might be very tricky. How would you let the client know about additional resources without labeling the client as emotionally unhealthy?

- Establishing trust and intimacy (ICF coaching competency number 3) will be established over time across cultural boundaries by demonstrating respect for the client’s beliefs and values (both individual and cultural). This process may take less or more time than in your native culture. It is not that trust is hard to build; it is more about how trust is perceived. To Westerners, trust is often perceived as being developed through a series of transactions during which the other person performs to defined standards. In other words, behavior leads to relationship. In many Asian cultures, a level of trust must be established before people respond appropriately; in other words, the relationship defines the behavior. To develop trust, the coach needs to understand the perception of trust that the client has incorporated into her relationship-building schema. Intellectual property, an ethical consideration, is also viewed differently in a collective versus an individualistic culture. In a collective culture, intellectual property might be seen as belonging to everyone rather than to an individual. If you are a member of an individualistic culture, and you find someone else is using your material without recognition or attribution, what do you do?

- Related to coaching presence, listening with intuition can transcend cultures. “Presence means bringing your self when you coach—your values, passion, creativity, emotion and discerning judgment—to any given moment with the client” (O’Neill, 2000). The intercultural coach effectively demonstrates curiosity, seeking to learn about other cultures, just as coaches, in discovery, seek to learn about clients. Tolerance of ambiguity and flexibility are key multicultural, as well as executive coaching, competencies. Realize that accepting cultural differences does not mean agreement, but, rather, not judging. Recognizing there are differences is the first step out of ethnocentrism, which, like level one listening (co-active coaching), filters everything through one’s own lens or that of one’s culture. More specifically, we hear the words of the other person, but the focus is on what it means to us.

While actively listening, the intercultural coach will attend to clients’ values and beliefs and how those things affect the clients’ ethical behavior. The coach might also address these issues while asking coaching questions. Examples of questions that relate to intercultural coaching include: “Will this action move you closer to honoring your individual or cultural values?” “If you make this decision, what values (individual, cultural) will you have honored?”

With direct communication, both creating awareness and planning and goal setting considerations include how direct or how polite to be, which may include how much, as a coach, to challenge perspectives and confront clients when they have not followed through with their committed action plan.

Understanding cultural perceptions, discerning trust-building processes, and expressing cultural curiosity are some of the strategies important in building intercultural competency. These strategies also apply specifically, however, to interactions between the coach and people of different cultural and ethical values.

- Humility, including not being afraid to not know, being willing to ask questions, and seeking understanding, is another aspect of intercultural coaching presence. Coaches should be aware, though, that in some cultures, those with status are expected to have the answers. This caution pertains to being respectful of the hierarchy of the culture. Some cultures have clear teacher/student roles rather than partnerships, and the coach and client will refer to each other by title and last name rather than by first names. (Do not assume!) Who is considered the expert, the client or the coach? Some Asians do not believe it is appropriate to ask questions of a person in authority. Who the expert is, and how she should be approached, vary from one culture to the next. For example, an American once told me (Marilyn) that he was corrected for calling a German by his first name at a business meeting. In Europe, coaches’ credentials and degrees may have more to do with being selected than in the United States. Be aware of how your status, gender, role, power, and culture are viewed by your multicultural clients.

Bridging Cultures: Case Studies in Ethics

There are three basic ways to view a person bridging cultures:

- A person moving into a new culture (inward looking)

- A person looking outward toward global business or the world in general (outward looking)

- A person working inside (looking within) a homogeneous culture

There probably is no such environment of complete homogeneity because physical or cultural diversities exist in even seemingly uniform cultures. For example, in China, people from Sichuan, Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong all have distinct languages, cultures, and behaviors.

When coaching executives who move across borders, one issue that repeatedly arises is how to respond to the culture of people that one meets. For example, one day as I (Charles) sat in a Shanghai office of a divisional VP of a large global company, I noticed that during the course of the day the executive, a native of India, received three telephone calls.

The first call was from an American. During this call, the executive reclined in his seat, put his feet upon the desk, and talked about baseball and the kids. His accent was almost a drawl, even though he was a highly educated Indian national, who spoke Queen’s English. Next, a call came from a Japanese colleague, to which the VP responded in a very upright position, feet on the floor, and using a soft, almost humble voice. In a following call from a Chinese employee, the executive leaned into more of an aggressive position, speaking rapid-fire, although friendly and courteous. My observation has been that quite often Indians are very observant and respond to people in ways appropriate to the other culture.

In another coaching session with a Swedish executive, I described this scenario, and his reaction was astonishment. He asked, “Why should I change myself to meet the culture of another? I am no chameleon!”

The ethical dilemma posed is how to match styles to improve communication, yet not sacrifice one’s own morals, culture, and ethics. Quite often, in crossing borders, we hear, “This is the way we do it here.” In some situations, such as matching styles for effective communication, some people would argue the necessity of conformance; others would remain solidly in their own paradigm. In other situations, such as when one is giving a payment or favor to elicit a sympathetic response, many other factors influence the decision process.

When one considers bribery, for example, as an unwarranted payment to elicit behavior or a favor that otherwise would not be bestowed, there are both macro and micro effects. Bribery is also a case of governance. The first macro effect is the law. As we have seen, most countries sponsor laws concerning the illegality of payments used to educe inappropriate benefits; for example, the United States has the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), mentioned earlier in the chapter, to which most American companies espouse compliance and concomitant zero-tolerance for infractions. Quite often, these laws are not enforced consistently at foreign subsidiary levels; however, nor are they enforced strictly by government organizations.

Illicit payments, besides breaking the law, lead to inertias in procurement and sales processes by fostering a need to negotiate outside normal business parameters. The transaction expenses add to overall product costs and the subsequent premium to the consumer.

A more insidious cost is the effect on morale within the organization. My (Charles) experience from working in organizations that tolerate even a modicum of corruption has shown me that teamwork starts to break down. When one person of a particular level of capability, and resulting responsibility and comparable reward, looks across at a colleague, what is observed is often the corresponding balance in capability and reward. If other colleagues have the same perceived capability, but with inappropriate levels of reward, such as that catalyzed by illicit payments, people naturally respond in less than cooperative ways.

Culture greatly affects this level of discontent. In the United States, India, and Japan, imbalances in capability and responsibility are likely tolerated to similar extents, but for much different reasons. In India, cultural influences of such religious beliefs as karma and cultural tolerance may allow a sense of “no expectations, no disappointments.” The United States has an environment of relatively high levels of job mobility. Individuals are generally aware that inequalities may exist during organizational change, and that these imbalances are usually transitory. These two aspects of organizations lead to a belief that “fairness” will eventually win. In addition, in the United States, the cultural tendencies of individualism and performance often drive discontent and departure from the organization. In Japan, intricate systems of relationship and obligation constrain behavior that runs counter to the prevailing sense of harmony.

In China, there are perhaps unexpected outcomes. Whereas in decidedly hierarchical organizations, persons in power rule without much employee discontent, with relationship more critical than performance, in emerging models of Chinese companies, merit-based reward systems play a major role in the creation of human-resource policies. A commonality in both forms of organizations is that people will often respond by creating an environment of doing what one is expected to do. This kind of organizational culture often leads to employees experiencing palpable apathy and passing responsibility upward.

When coaching a South African executive moving to Japan, he mentioned to me (Charles) that he was having difficulties in reaching out to the Japanese. As we explored the reasons for his discomfort, he said that, as an Orthodox Jew, he was allowed to bow to the Japanese priest only once a year, thus causing him to be hampered in his attempts to show respect. The question then arises: “Should one forsake one’s own morals to avoid cultural chauvinism?” In this case, we explored using such other outward behaviors as fluency in Japanese greetings to demonstrate his awareness of Japanese culture. This led to other interactions at work as he learned appropriate behaviors from Japanese colleagues directly.

When coaching people in intercultural settings, one should be aware of how cultural differences affect relationships and performance. Neither the coach nor the client may be aware of the specific cultural factors that are governing results; therefore, the coach has to ask questions that draw out possible client inertias to effective ethical frameworks and behaviors. An example would be to explore the level of responsibility that a person takes in intercultural communication. In answers to such queries, intercultural coaches often hear such comments as, “They do not understand me,” “They do not listen very well,” or “They never speak in meetings.”

One approach to helping clients transcend cultural barriers is to motivate them to seek out the cultural or organizational reasons for the seeming lack of understanding or response. Another approach is to explore the clients’ own capabilities to assume responsibility for suboptimal communication.

Conclusion

This chapter examines how ethical variances among cultures affect the process of coaching people of different cultures. The framework was set by looking at what culture is, and how cultural values drive ethics, noting the distinction between cultural and individual values in coaching. We have identified awareness as a primary competency in intercultural coaching, including both creating awareness in the client and an awareness of the client and coach’s cultural values and ethics. Action is a necessary adjunct to awareness, and we explored who will do how much adjusting when it comes to intercultural variances, including ethics.

Considerations in the intercultural coaching process include cultural variations in building trust and establishing credibility; indirect v. direct and formal v. informal communication; confidentiality; the importance of presence; and evaluation of situations from an intercultural perspective. Awareness leads to knowledge and, when applied in practice, develops competencies. Coaches may also serve in co-creating a neutral third culture or space that bridges cultural gaps, a place where diversity can be leveraged and celebrated, and each person’s contribution recognized.

Intercultural coaching ethics, especially when coaching with organizations, also is affected by legal and governance issues. Governance, or the process by which an organization or society conducts its behavior, is one spoke of the rudder, with leadership and transparency comprising the other two spokes, that guide organizations through ethical decision-making processes. Here, the coach’s role in developing leaders and teams in intercultural organizations is to support the same intercultural competencies required of the coach (flexibility, global mind-set, nonjudgmental approach, curiosity).

The cases and discussion presented again demonstrate the key question of who does the adjusting, and how much, in relation to intercultural values and ethics. The intercultural coach can help individuals maintain integrity—clarity about ethics and how to apply them in the multicultural environment.

The role of the intercultural coach as an agent of integration and transformation is supported by the competencies of flexibility, curiosity, humility, and global mind-set. Awareness is identified as a primary competency in intercultural coaching, including not only creating awareness in the client, but also an awareness of the client and coach’s cultural values and ethics. This awareness can prevent ethical dilemmas and transgressions.

References

O’Neill, M.B. (2000). Executive coaching with backbone and heart. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Said, E.W. (2002). Culture and resistance. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

Notes

1News sources for this section: China Daily, November 9, 2004; Caijing, April 4, 2004; Wang Yichao, Zhang Fan, caijing.hexun.com/english/2004/040420/lucent.htm; “Lucent Fires Top Chinese Executives for Bribery,” by Sumner Lemon, IDG News Services, April 7, 2004; China Daily, April 18, 2004