Leaders Often Underestimate Leadership

200 Souls

The year was 1945. My grandfather, together with millions like him, returned home from the war to a bleak welcome. His family’s house in South East London had been extensively damaged in the war. My father and aunt (then just children) and my grandmother were in dire need of warmth, nourishment, and a roof over their heads. The arrangement in those days was that everyone returning from the front had the right to take up the job that he or she had held before the war, but unfortunately, my grandfather’s former employer no longer existed. It had been razed to the ground during the Blitz. Without the safety net of a social welfare system (such support was years off), my grandfather’s position was precarious, and it was obvious: his family’s mere survival depended upon him finding employment–and fast.

He applied, it is said, for hundreds of jobs. It was not that he was not employable. He had skills, experience, and no end of drive, but he was not alone. There were literally hundreds of thousands like him searching for and applying for the same positions. In such a saturated market, standing out from the crowd can prove very difficult. Nevertheless, eventually, he returned home one day with the news that he had been offered a job. My grandmother, whom I sadly only had the pleasure to know briefly while I was a small child, was apparently a woman of few words. Family lore says that she was only known to show her emotions on a couple of occasions in her life. The day my grandfather came home with the job offer was one of those times.

My grandmother danced around the front room with the children, smiling across her face as she sang, We’re saved … everything is going to be alright … Daddy has a job…. However, my grandfather did not have a job. He had indeed been offered a position to work as a London bus driver, but he had turned down the offer. He had not taken the job.

Apparently, that was the second time in her life that my grandmother showed her emotions.

With sheer consternation, she harangued my grandfather for what she viewed as an awful decision. How could he turn down such a job offer, such a gift? How could he put his family’s welfare on the line with such a decision? She pleaded. My grandfather, whom I never met as he sadly died before I was born, solemnly responded to his wife’s vociferous appeals:

Darling, I turned down the job, because I did not want the responsibility of 200 souls on my bus.

After much consideration, I, personally have come to the firm conclusion that I am hugely impressed by my grandfather’s decision. He had the strength of conviction to make such a difficult decision despite acute awareness of the potential ramifications for others (his family). He put his values before potential material gain when he decided that he did not want to bear such a large responsibility. Some may see such a move as cowardly or feeble, but not I. For me, he had reflected on and made the most important and wide-ranging decision a professional can make, namely:

Do I want to take on the responsibility?

Leaders bear the burden of responsibility, irrespective of industry. In my nearly two decades as a management consultant and coach, I have unfortunately heard regret expressed by hundreds of leaders, from many different industries.

Sometimes, I wish I had never become a manager! This is not what I had thought it would be like…I am not cut out for this…I wish I had more time for my family…I take these issues home with me…it consumes me…being a leader has made me ill. Et cetera.

My message here is not that leadership and management are solely bad stars to follow and should not be recommended as career paths. On the contrary, leadership can be powerful, exciting, stimulating, and hugely rewarding. Leaders have the chance to make a difference.

The message here is that leadership is not for everyone.

Maybe you are just embarking on your professional career, maybe you are looking forward to imminent promotion to your first leadership role, or maybe you are already in such a role. Wherever you currently find yourself on your professional or leadership journey, I implore you to seriously self-reflect and ask yourself whether you truly want the responsibility and all the trappings and challenges that come with leadership. Before you read the rest of this book, you should be able to honestly answer the question:

Do I want to drive the bus?

Would You Push the Big Guy?

There is an exercise that psychology professors sometimes run with their first semester undergrads:

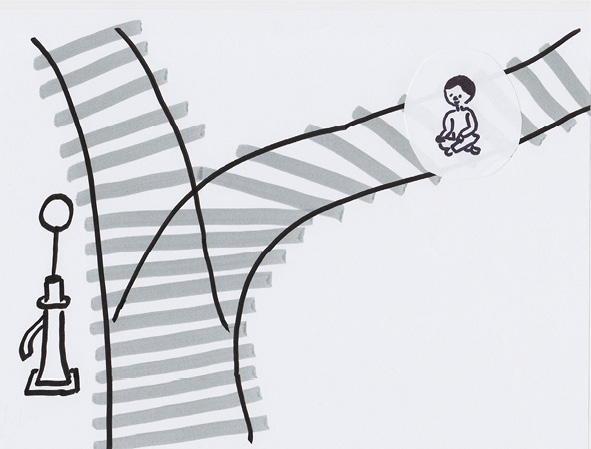

Imagine you are casually going for a walk, minding your own business when you hear the sound of a train in the distance. You turn, and from your position, you can see the train fast approaching. Suddenly, your attention is piqued by a group of youths (seven or eight of them) playing on and near the track (Figure 1.1). They appear to be oblivious to the approaching locomotive. You call out to them to move, but they cannot hear you. Just as you are calculating whether or not you will have the time to run to them to warn them yourself (you will not), you notice that you are standing next to the controls that switch the points. If you were to switch the points, the train would follow the side track and the youths would be saved.

Figure 1.1 Would you switch the points?

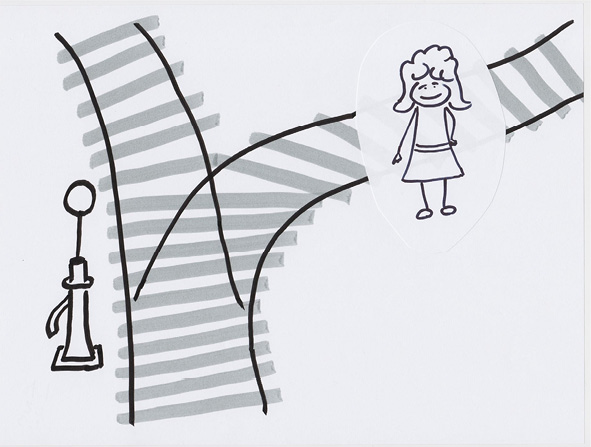

In a freakishly similar situation, you find yourself, days later, by another train track. You again witness 7 to 8 people dangerously on or by the rain track (Figure 1.2). A train is fast approaching and will surely kill them all. They cannot hear you. You cannot make it to them fast enough. But, you can switch the points. However, there is a young child on the side track, on the track that you would divert the train to, if you switched the points. You cannot warn or reach either the lone girl or the group of youths. What will you do?

Figure 1.2 Would you switch the points?

Days later (you seem to be having some bad luck on your walks in the country), you find yourself in the same situation again (Figure 1.3). The same as before, but in this case, the single person on the side track is someone very dear to you (for example your mother, partner, or sibling).

Figure 1.3 Would you switch the points?

Several days later (déjà vu?) you have decided to change your route through the woods, and instead wander along the top of the hill, overlooking the train track (Figure 1.4). Tragically, you witness a similar situation: a group of people is playing on the track, but this time, you cannot reach the controls to the points in time. You cannot verbally or physically warn the kids that the train is coming. Their fate appears doomed. However, near you, you see a huge man. He must be nearly seven-feet tall and weigh several hundred pounds. He is a powerhouse of a man. Strong, ripped, massive. You quickly surmise that, if you were to push the man from his vantage point on the hill, he would fall in front of the train causing the driver to brake or his large body would slow the speed of the train enough to save the loitering teenagers.

Figure 1.4 Zoo map: you are here

Would you push the big guy?

Admittedly, the preceding situations are extreme. Let us hope neither you nor I nor anyone we know is faced with such intense dilemmas. But, the truth remains that, were we to find ourselves in such high-pressure scenarios, we would have to make a decision. One way or the other.

Reacting to the previous scenarios, almost all subjects asked, choose to switch the points to divert the train to the side track in the first example. When asked, most respond that they would intervene if they felt that their actions could benefit the group. Only a small percentage of respondents say that they would do nothing at all. Indeed, I have also run the example with numerous groups myself, and one or two over the years have answered thus: It was their stupid decision to sit near a train track, so why should I get involved in their lives.

But, the vast majority chose to switch the points. When faced with the second of the dilemmas (1.2.2), the majority, also here, claim that they would switch the points. The most common defense of their actions sounds something like this:

If I were forced to make such a decision, I would choose to save the many over saving the one. Seven lives are more valuable than one.

Interestingly, the water is muddied considerably when people are asked how they would act in situation 1.2.3. The most still choose to save the many over the one, but a not-insignificant minority state that they would save their loved one and let the train kill the group. I have asked this question of thousands of workshop participants, and many chose to leave the points as they were in favor of their family member. Indeed, in some groups, more than half decided in that way. It appears that blood is, indeed, at times, thicker than water and that—contrary to the statements to 1.2.2—sometimes several lives are, in fact, not more important than one. Even more interestingly, subjects in this study often change their mind again and choose to switch to save the youths after all, when they are faced with the knowledge that their loved one on the side track is very old or terminally ill.

When responding to whether or not they would push the big guy, the most do not. They argue that he is not even involved. He is minding his own business and so should not have to die to save the youths. It would be unfair for to sacrifice him as he has done nothing wrong. Here, the several-lives-are-more-valuable-than-one argument also does not seem to apply. When asked to reflect on this situation, many state that it is different from 1.2.2 or even 1.2.3 because the people on the side track in those situations chose to be involved. They chose to sit in a dangerous spot. The big guy chose not to be involved and so, should get a pass. Some do choose to push the big guy to save the many, but in my experience, such a choice is rare. Leaving the matter of what may or may not be legal in any particular jurisdiction in those situations to one side for the moment, let us look at the forces at play, when we have to make such momentous decisions. These decisions (and many we make) are based on our values.

Our journey through life, our upbringing, the culture(s) we have lived in, the people we have met, and the experience we have made, even the languages we speak (Pinker 2003), these influences and many more mold our personal values. These values, often referred to as our internal compass or as common sense are, in fact, not common at all. Our values are unique to us. Each of us will have differing views and instincts depending upon the complexity of any given situation. Your challenge as a leader is to tap into these instincts, listen to and understand your inner voice, and then translate your values into action, decisions, and judgments.

In the preceding example, maybe you sacrificed the (one) child to save the (many) youths. Maybe this many-lives-are-more-precious-than-one equation was rejected when the one was your mother or brother. Maybe you did not push the big guy because he had not done anything wrong. After all, the child was stupid enough to play on the tracks in the first place. Or maybe, you pushed the big guy to save the many.

Leaders have to make difficult decisions every day. Fact. Should we hire the less-qualified single father of three or the better-qualified university graduate? Should we build that plant next to the river? Should we recall millions of products and suffer huge losses because one box contained a shard of plastic? Should I fire the employee who broke company rules and was in breach of his or her contract, although he or she happens to be a dear friend? Shall we make those 300 people redundant to remain profitable and able to employ the other 900? Should I, as a leader, stand up for my team, against the wishes of my own superior, and in doing so, risk my own job security? Should I choose to delegate the awful task or carry it out myself although I have neither the time nor the inclination?

Leadership can be extremely challenging, and it is hugely important to me that you have reflected on this deeply, before you enter into management. Leadership involves making difficult decisions, and these decisions will be based on your values and strengths. I invite you to reflect on what is important to you; on what your values are.

Driving the bus can be immensely rewarding. You get to choose the route and speed of travel. However, wanting to remain a passenger is absolutely no disgrace. Taking the bus on your journey is fine. Indeed, having others drive you can be positively pleasurable at times.

You alone can, and should, decide. Do you want to drive the bus?

You Are Here

When I was a child, my parents used to take my brothers and me to the zoo. I remember one time, the air conditioning in our car was broken, and so we had to drive through the safari park melting in 35 degree heat while the monkeys ripped the car to shreds. Lambs to the slaughter. Either way, the color and tone of the zoo always fascinated me. The myriad creatures with their different habitat and dietary demands, also. The zoo’s employees whose role is to create as comfortable an environment for their animals as possible while, at the same time, building a suitable ambiance for their customers, the visiting public. I loved visiting the zoo.

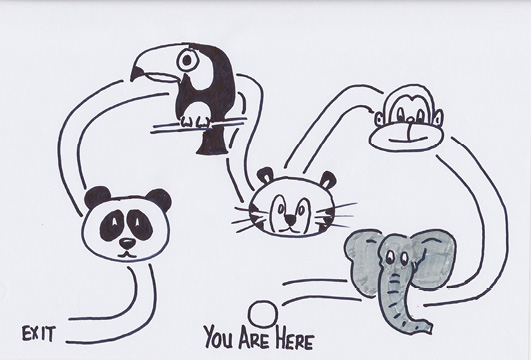

Moreover, one thing always struck me when I entered a zoo or a safari park. The first thing one sees when one enters such a park is a large board with a map on it (Figure 1.4). It shows you where all the animals can be found. The elephants are at the back of the park, the penguins are just round the first corner, the lions are on the right side, and so on. Oh, and it, of course, showed us exactly where the overly priced gift shop was. At the bottom of the sign, though, there was always a large red dot and with an arrow pointing to it together with the label: “You are here.”

That red point allowed you to get your bearings. It allows you to appreciate where you are in relation to other attractions, and some people find that they save a rough picture of that map in their minds while traveling through the zoo and recall it at will to help them guide themselves, all the time, referring back to that point: “You are here.”

Okay. Now, save that thought, and we will return to it in a moment.

Next, if you work for an organization, think of that company’s structure. If you are thinking of joining a particular company to be a leader in the future, then think of that corporation.

Now, think of the following numbers for me. If you like, write them down on the largest piece of paper or whiteboard you can find:

- How many people work, in total, for your company?

- How many of the employees at your company are in leadership positions?

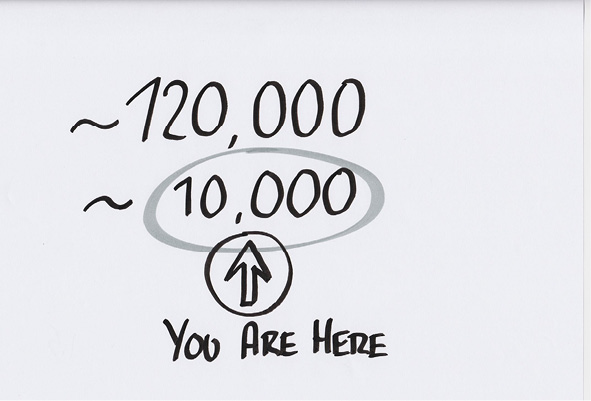

What kind of numbers have you written down? If it is a large company, maybe 10,000 of its 120,000 staff are managers or leaders. If it is a smaller company, maybe those numbers are around 50 of 300. Maybe you have other numbers (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 Even junior leaders are part of the they

Whichever two numbers you are now looking at, draw a big, fat circle around the smaller one, that is, the number of people who currently fulfill a leadership role at your company. You are here!

You are a member of the elite party of leaders in that corporation. You are the they that people talk about (usually when complaining that change is not possible or things are not as we would like them):

“They (the managers of this company) have created a culture of pressure, here.”

“They will not listen to us, even if we spoke up.”

“I would love to change things around here, but they will not let it happen.”

If you are a manager, you are part of the they, already. Even if you are not yet in a leadership position, but consider that your aim, then, one day, you will be one of the infamous they too. They are not some mystical, untouchable, unapproachable group of ghouls. They exist, and as a leader, you are one of them. In other words, both your mindset and your language should change as soon as you take on your first leadership position. You are no longer able to blame others for the woes and weaknesses in your corporation. As a leader, you also no longer have the chance to pass the buck to others who should make the challenging decision in your stead. In the following chapters, we will look at more specific leadership situations and reflect on the best course of action to avoid the most common leadership pitfalls. However, before we do so, we need to digest the generic, fundamentals mentioned. Do you want the responsibility of leading a team? Do you know what is important to you as a leader? Have you reflected on your values, and how they will influence your decision-making? Are you prepared to make big decisions? What decisions would you make in different, precarious situations? Have you yet arrived at the mindset that, as a member of corporation management, you are part of the they that people talk about? As a leader, you have the exciting chance to steer the bus or at least be involved in the steering, but you will have to make some big, tough decisions along the way.

Chapter Leadership Challenge

Take a piece of paper and a pen and write the words my values in the middle of the page. Circle that phrase (Figure 1.6). Now, take your time, reflect deeply and add to the page, round the center words, everything that is important to you and is guided by your inner compass. Where do you stand on the train dilemmas, for example? What are your values regarding difficult employment and recruitment scenarios? How do you feel about delegating, taking on tasks you do not like, discussing sensitive information, disciplining staff members, and on all the other management settings you can think of? Use this mindmap to develop a collection of your own values. Use this list to decide if you would like to drive the bus (and how big your bus should be) and keep it with you on your journey and refer back to it periodically.

Figure 1.6 An example of a leadership value mindmap