Leaders Micromanage and Focus on Details

The Golden Circle

It is own-up time. I never used to like to read. I know that may seem strange for a linguistics graduate, former owner of a communications agency, and author of several books, but I promise, in the past, I found it hard to focus on intellectual reading unless I felt I had to. At school or for my college degrees, I begrudgingly picked up the literature on my teachers’ and lecturers’ recommended reading lists, but I painfully struggled, unmotivated through those works and only because faculty had told me what to read. My university lecturers sounded something like this:

“In semester 1 Jones, Edwards, and Carr are compulsory reading, and make sure you have read Laing and Brownbridge and Clarke, Henderson and Hill by the end of semester 2…”

Years later, during the first stages of my career as a management trainer, I was lucky enough to have worked on successful training projects and felt that, if the last client was happy, then the next one also would be. I felt confident of my abilities and I felt little need to go back to the books, certainly not to the ones that my lecturers had forced me to read at university. However, around the same time, I began to have the benefit of tandem training with a number of renowned, highly experienced, and gifted management consultants. I loved to watch them, learn from them, and tried to soak up their techniques and tidbits of knowledge. I was inspired by them. One thing that they all had in common is that they all read all the time! All my trainer colleagues ever seemed to talk about was this book or that author. They were an inspiration to watch deliver their workshops, and they soaked up the contents of subject literature like sponges and then suddenly, I saw the connection. I saw the reason to read.

If I too were to read as they read and read what they read, then maybe I, too, would be able to train and coach as inspirationally as they did. In summary, what my lecturers failed to do during my time on campus was to help me understand why I should read the books they recommended. They told me what to read ad nauseam (the recommended reading lists were stapled to the back of every handout, were pinned to every noticeboard, and filled the final presentation slide of every class), but we were never told or shown why reading this book or the other would help us on our personal development journey.

My lectures started with the what.

My trainer colleagues at the beginning of my career, started with the why1

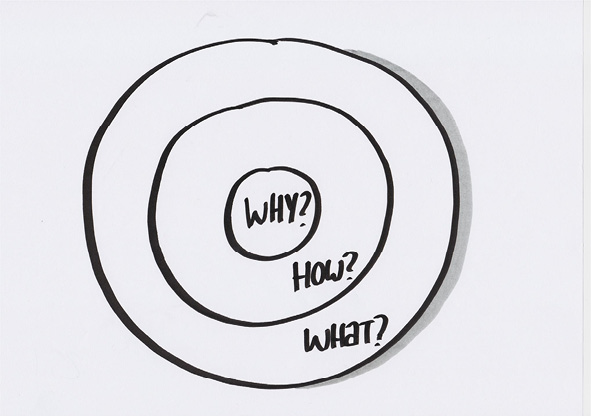

What, how, why. This explosively simple model comes to us from speaker and leadership expert Simon Sinek (2009). The golden circle, as he calls it, explains that to inspire and motivate we should start with the why, not with the what or how (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 The golden circle

Successful companies have long since known that starting with the why is the most powerful way to create saleable products and convince people to buy them. What companies like Apple(TM) have become adept at doing is convincing us that having a particular tablet or gadget in our lives will ease communication, improve our efficiency, and generally better our experience. They explain to us why we need it in our world. They do not bombard us with how many gigabytes of RAM it may or may not have or how fast the CPU is. That is the what, and we can get to that. They start with the why, then lead us on to the how by showing us demos of happy customers swiping or pinching their tablet screens. The what is almost irrelevant to us, after that; just a bolted-on afterthought.

As a leader, first, explain to your team members why you are asking of them what you are asking of them or why you as a team are embarking on this course or setting up that project. Do not begin with the details of when the project meetings will be, what the project will be called, who will have which responsibility, and how the subteams are expected to communicate with each other. Start with the why. Help your associates to understand why they will be doing what they will be doing. When your team identifies with the why, they will develop better and better ways of how to accomplish the goals and the what will top all expectations. Your role as a leader is not to instruct intelligent, experienced, creative, out-of-the box thinking professionals on how to do their jobs, and it is certainly not to stubbornly remind them what they are producing or what service they are providing. Your role as a leader is to inspire them to appreciate what will be different when they have gone through those walls for you and the organization. Your role is to regularly and emotionally remind them of the why.

And remember, company values may differ from personal values (i.e. the why). Take the VW emissions scandal in recent years by way of an example. Mistakes were made, no doubt, and a culture of secrecy and deception seemed to have established itself in certain parts of the company. At least for a period. But, at the end of the day, decisions are made by people. The VW members of staff made certain decisions, some of which proved to be unethical and illegal, but these values probably differed from the company core principles. Decisions are made by people. Decisions are not made by corporations. Those people-made decisions are swayed by personal values, and those values are the most delicate of leadership tools.

Leadership by Kitchen Table

Leadership is not a job. It is a mindset. There is no definitive list of characteristics that make up the perfect leader (Clifton, cited in Rath and Conchie 2008), and there are also no easy wins or quick fixes. Leadership is a constant reflection and reading of why a situation has developed and how to solve it. Irrespective of whether you are leading in business, industry, arts, armed forces, medicine, education, charity, civil service, religious institution, club or foundation or any other kind of organization, you will need to hone your leadership antennae.

My mentor and crackerjack Canadian leadership consultant Christiaan Lorenzen brilliantly slices the question of what makes a good leader down to a form that makes it comprehensible for any budding boss. When searching for the why and the how of leadership, all you need is to return to the kitchen table.

Leadership by kitchen table is, according to Lorenzen, the art of revisiting the communication basics we learned at our family’s meal-time table. Think back to those gatherings. What fundamentals did we hear from our parents, guardians, or family? We picked up striking, focused, sticky messages of self-development, including (although the basics at each kitchen table no doubt vary somewhat) maybe the following:

Discipline: “Please be back in from play in time for dinner”, my mother would say.

Self-management: My brothers and I had to wash our hands and look presentable at our dinner table.

Culture: The local rules of our table were learned from my parents, and subsequently taught by my brothers and me to visiting guests. At ours, these included passing dishes to those who could not reach and thanking whomever had prepared the meal.

Communication: “Tell us about your day, son.” My father would invite, encouraging us to express ourselves communicatively, while also challenging us to actively listen to other discussions. “Listen to this story from your grandmother. You’ll love this.”

Transparency: If my brothers and I squabbled, our parents would encourage us to openly express our feelings toward each other and search for resolutions.

Delegation: The one who cooked needed not wash up. Also: “Would you serve, while I carve, please?” Dad delegated.

Strengths orientation: One cooked, one chopped, one laid the table, one played the piano to entertain after dinner, and everyone tried to tell the jokes (they were rarely funny!)

That is roughly what it looked like and sounded like in our dining room, growing up, and the fascinating thing is, and this is what Lorenzen is referring to, I have always lead my teams by the same principle values I learned at our kitchen table.

My communication is always transparent, active, and two-way, I delegate continuously, work hard to cultivate a culture of confidence and trust, I am diligent and self-disciplined, punctual, and honest, and I endeavor to manage strengths-oriented. I also like to tell (bad) jokes. But I get others to play the piano!

Our values in the workplace should be no different from what is important to us in our private lives. The way we treat people, the way we would like to be treated; I argue that there should be no difference at work. Some managers talk of being different at work. Why? The principles we learned at the kitchen table are those that guide us through our lives: basic fundamentals of respect, honesty, discipline, transparency, communication, and so on. Why should we not carry these values with us at the office?

For example, when two of your team members find themselves in a conflict, return to the kitchen table and reintroduce the essentials of transparency and honesty. Create an environment where both can candidly express their opinions.

If you feel that office rules are being bent, lunch breaks are getting longer, and personal matters or private distractions are detracting from the team’s performance, return to the kitchen table and reinforce the importance of discipline and focus. Be a role model and show punctuality and discipline yourself and encourage others to follow suit.

When you find yourself in a sticky leadership situation at work and you are hard-pressed to find the right solution, return to your kitchen table. What value(s) would have been a foundation of your behavior then?

Identity

When I was 20, I was living on campus at university in London in the United Kingdom with five other guys renting an apartment. We shared cars to attend lectures, played sports together, had PlayStation marathons, and spent lots of the evenings partying and hanging out (environment). I was boisterous, loud, fun-loving, provocative, and hugely energetic. I also worked part time behind a bar to make a few bucks to pay for nights out (behavior). The only books I read were related to my studies, I knew a bit about the subject I was majoring in, but I knew a lot more about where the best karaoke nights and club nights were; I knew the pizza delivery number off by heart and my knowledge of premier league soccer was comprehensive. I was not very computer literate at that stage, but I was au fait with finding quotes from the right books in our extensive library to impress my professors in assignments (knowledge and skills). I loved the freedom of having recently left home for the first time and thought little about the future. I was invested in having a good time, learning, and making friends, and my attitude was to always try and get the most out of my time at the university (values, beliefs, and attitudes). I was a student. I saw myself as a free spirit, a friend, and the future of my country (role). I proudly wore my university’s livery and colors at any opportunity, gave my all in the soccer team to beat competing colleges, and then sang traditional drinking songs with my fellow students to celebrate victory and taunt our defeated opponents. I would have laid down in traffic for my friends, but was single and did not have any children (affiliation).

20 years on and my life looks quite different. I have two children, I am married, and my wife and I own our own house in Germany with a yard for the kids to play in and a garage to park the seven-seater in (environment). I work and travel all over the world to different clients, and my wife and I spend our evenings enjoying a cup of tea on the deck, playing games with the kids or streaming new TV series (behavior). I have picked up a lot of knowledge about leadership, can recite most management models from the literature of the last 50 years. I have learned and developed facilitation techniques and know the airport codes for most hubs in Europe. I have also become quite handy with woodwork tools, around the house (knowledge and skills). I believe that my hard work and strengths orientation will help my family and me enjoy a good life (values, beliefs, and attitudes), and my role today is that of a parent, husband, and breadwinner (role). Everything I do in my life is for my family and in particular to build a safe and loving environment for my children to grow up in (affiliation).

I am sure you will agree; that much has changed in my life in 20 years. It has changed for copious reasons (some planned and many accidental), but what is clear to me is that how I act and think today (my attitudes, behaviors, skills, and so on) has changed because my affiliation has changed. Affiliation, that is, your feeling of belonging, affects your attitudes, skills, behavior, and environment in an unstoppable cascade. Change your affiliation and your actions and drivers change. At university, my affiliation to the student life and to my alma mater inspired and influenced all my enterprise and wants. My current affiliation (my family) has driven a trickle-down change in everything I do and why I do it.

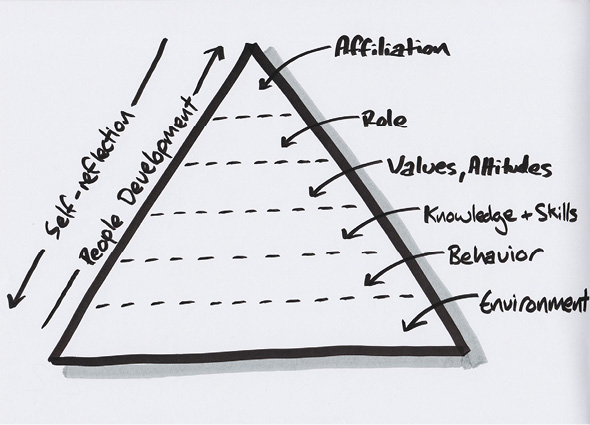

This model is adapted from Robert Dilt’s Logical Levels model (Figure 2.2), which originates from neuro linguistic programming (Tosey and Mathison 2003). Dilt’s levels, often used in coaching, can function as an excellent self-reflection tool, but contemporaneously, also as a leadership mechanism.

Figure 2.2 The logical levels of leadership

We can use Dilt’s model to ascertain which slice of somebody’s experience they are currently focusing on. In doing so, we can help them better understand and self-reflect on their decisions and chances, and potentially, help develop them further. In order to sustainably affect behavior, it is vital to keep the person’s values and beliefs in mind and to understand their role and to what they are affiliated. Leaders sometimes tend to approach a conflict or issue by attempting directly and pragmatically to solve the situation they see. Using the five levels from Dilt’s, leaders can develop a better appreciation for why something is happening and fix it there, at the source.

Environment tells us about the where and when something is happening. It describes the setting and is important in establishing who is involved, where something happened and what the surroundings are.

Behavior tells us about what is going on and how people are acting. It is often what is noticed first about a person and is the side of people that others tend to talk to each other about. “He did this, she said that….” Behavior can be both verbal and nonverbal.

Knowledge and skills refer to a person’s capabilities. What have they learned and how that is affecting their actions. It represents the how. In order to show behavior, someone has to draw down on a skill or on previously learned knowledge.

Values, belief, and attitudes often drive our behavior. The frustrating thing is that people are often not completely aware of what values and beliefs they hold. We may feel, instinctively and internally, that a particular course of action is right or wrong. This path of visceral; intuitive decisions can be traced back to our values, beliefs, and attitudes. They represent personal motivation and help us understand why someone acts as they do. Personal values may differ greatly from person to person and can be notoriously difficult to shake or adapt. We carry them with us always.

A role tells us who we are. We each have our own sense of self. Understanding our role helps us to appreciate why and for whom we are doing things. In this scenario, it does not refer to the role printed on your business card, but at a higher reflexive level; what are my responsibilities and on whom am I dependent and who is dependent on me.

Finally, taking its place at the very peak of the logical levels pyramid is affiliation. It can be difficult to put your finger on exactly what it is that you identify with, but according to Dilts, it drives everything else. All your beliefs, decisions, behavior, and so on. When we discover to what we are affiliated (i.e., a sense of belonging), it can be a very emotional experience and can be extremely powerful. To begin to understand your affiliation, ask yourself: Do I feel part of something greater than just me?

To grasp how affiliation cascades down to affect all the other levels, consider the assembly-line worker for the luxury car company, who will never be able to afford the product he makes and yet wears their branded clothes in his spare time, sports a tattoo of their logo on his forearm, spends what little money he has traveling to support their racing team, and collects miniature models of their cars. He identifies wholly with the brand, and this identity precipitates his role, behavior, and environment he establishes for himself.

Or, consider the young college undergrad, who despite having very little disposable income, spends all of her student loan to buy the latest laptop computer from Apple, which costs three times as much as a no-name notebook. A PC may suit her particular computer needs better, but she is determined to have a shiny Mac. she wants to be part of the gang. She already uses the smartphone and smartwatch made by the same company and all her friends have MacBooks. They are sleek, stylish, and totally cool. She identifies with the modern, dynamic image and believes that Apple have simplified the world with their intuitive devices, and that the Apple brand exudes class and modernity, yet she chooses to ignore the stories of poor working conditions for Apple subcontractor workers and the accusations of tax avoidance. Her environment, behavior, skills, values, and role have all been ultimately driven by her affiliation to the brand. Understanding to what your people feel affiliated can help you better understand their actions.

The model really comes into its own when we leaders are faced, together with our associates, with problems to solve. Apply the following two-step approach:

- Identify at which level the problem is being caused.

- To solve that problem, contemplate the situation from the perspective of a different logical level.

For example, if you witness unusually petulant behavior in one of your associates, assess their environment or their skills and knowledge. Might they be uncomfortable in the office in which they work or might they not possess the requisite skills to calmly perform their duties? If a team member lacks the knowledge in a particular field, coaching them on developing their admiration for the positives of training could affect their behavior. If a colleague is adamant that using very direct communication at all times is just and right, no matter how much others are offended, use the logical levels to better understand what his or her intrinsic beliefs and values are.

As Lowther (2013) puts it, “By shifting neurological levels, solutions to the problems become obvious.” Understanding how the levels present themselves in your team and how they induce behavior can help you to coach them at times when they struggle with conflicts or are faced with challenges and so on.

Chapter Leadership Challenge

To be able to sell the why, we leaders first have to have bought into the why ourselves. Ask yourself at regular intervals why. Why are you at this organization and not at another? Is it for logistical or pragmatic reasons? Is your workplace close to your home or your children’s day care? Or, is there another reason? When you applied for the position, what were the motivations for enquiring? Were you simply looking for something to pay the bills or was there another reason? When projects come down from your superiors, do you ask why the company is going in that direction? Can you see the big picture? Can you connect the dots?

1 Luckily, I have known the how (to read) since my mother taught me as a child.