We would like to start with a story to help illustrate the importance of effective teamwork in health care, and how breakdowns in teamwork and communication impact patients and their families. This story relates the experience of one of our family members.

My mom had been living with a painful shoulder for years, waiting for the orthopedic doctors to determine that her situation had deteriorated to the point that joint replacement surgery made sense—essentially when she reached the point where it became bone-on-bone. She was thrilled when she learned she finally qualified for the procedure, as she knew it would relieve the pain she had been dealing with so for long—not to mention that it would allow her to return to some of her favorite activities, such as gardening.

The procedure was scheduled for a Friday afternoon, and afternoon quickly turned into evening as the day’s cases backed up. Eventually her name was called, and the surgery was performed. I was sitting with my dad when the pager went off close to 7 p.m. to let us know she was in recovery, and that the surgeon was ready to meet with us. He reported that all had gone as expected and that they had placed a block in the upper back/shoulder region to help with the pain, a standard practice with a good track record of success.

The next day she was feeling quite good, was pain free (due to the block), and the on-call physician assistant (PA) determined it was safe to discharge her. Of course she was excited—who wouldn’t rather be home in their own environment? As she and my dad were getting ready to leave, she felt a few twinges of discomfort in her shoulder. The nurse assured her this was normal and that there was nothing to be concerned with. They gave her oral meds for pain control and sent her on her way.

My parents live on an island in the pacific northwest, so we decided it would be best for them to stay with us for a few days (just outside of Seattle) until she felt well enough for the trip north. They left the hospital and drove to the ferry dock (I live on a peninsula, a 30-minute ferry ride away). When they arrived in the ferry line the pain had increased and she was quite uncomfortable. They called the number on her discharge papers and were told she should still go home and that she could take the oral meds. The pain continued to increase and soon her shoulder felt as though it were on fire. They decided it was time to return to the hospital.

They presented to the emergency department and chaos ensued. They had trouble controlling the pain, and the emergency department (ED) doc was concerned about infection—her shoulder was extremely discolored (we would later learn that this is actually quite normal with shoulder replacement surgery, but at the time it created additional concern and stress). There was no apparent communication or coordination with the orthopedic team, including the on-call PA, which led to ongoing confusion about her condition and how best to treat the pain.

Early Saturday morning she was finally admitted to an inpatient room, but there were continued challenges managing her pain, and confusion seemed to reign for the rest of the day. On Sunday I was able to make it over to the hospital and spoke with the charge nurse, expressing my concern with the lack of a plan and team coordination. She agreed and contacted the on-call PA (the same PA who had not taken the time to see her when she was readmitted to the ED), who finally, after more than 36 hours, came to my mom’s room. The surgeon was eventually consulted via phone and a plan was established to manage her pain. Two days later she was finally able to go home to continue her recovery and rehab process.

Lessons learned from this experience:

• The orthopedic team had no contact or coordination with the ED physician after the readmission, a clear breakdown in communication that led to the ED physician raising concerns about infection, because she was unfamiliar with the procedure and didn’t know that the trauma she saw to the shoulder and upper arm was actually quite normal. If the PA had connected with the ED physician, this confusion would have been eliminated.

• Miscommunication on the inpatient unit between the nurses and the orthopedic team—the nurse was concerned with my mom’s condition, but was covering from another floor and was uncomfortable speaking up. I have to give the charge nurse credit for being assertive with the PA and calling attention to the situation and lack of a plan, but it took far too long for this to occur.

• The family members (or others who provide the support network for the patient) should absolutely be considered part of the team. We know this is controversial with some, but if I had not taken the initiative to voice our concerns (knowledge of the health care system was definitely an advantage) the delay in managing my mom’s pain would have been even longer.

Most people you speak with in health care today will tell you how important teamwork is to achieving effective and safe patient outcomes. The environment and processes are so complex that no one person can do the work alone. Yet many practitioners express dismay at how challenging it is to actually have good, effective teamwork. The folks at the hospital where Kurt’s mom received her care were not bad people. In fact, once Monday rolled around, a team of nursing leaders swooped into her room to interview her in order to learn more about why the readmission had occurred (clearly, readmissions were something the hospital was closely monitoring, with the new pay-for-performance realities). They were thorough and certainly concerned about what had happened, and wanted to learn so they could correct the problems. The nurse manager was very receptive to the feedback and promised to convey our story/situation to other leaders on the floor, including physician leaders. The question still remained: how would they actually change practice to further minimize the chance that something like this would occur again? The answer is less clear.

Multiple studies have consistently demonstrated that clinical providers struggle with speaking up in instances where there is concern over a colleague’s competence, clinical decisions that are deemed questionable from a safety perspective, being treated unfairly, being belittled, and so on. The Joint Commission estimates that upward of 70 percent of adverse events in health care are due to communication breakdowns and some safety officers we have spoken with believe this percentage could actually be higher (2005 National patient safety goals 2005).

One study conducted by VitalSmarts, entitled Silence Kills (Maxfield 2005), found that 90 percent of the time health care practitioners do not voice their concerns when dealing with issues such as competence, unsafe practices, and disrespectful behavior (to name but a few). This finding is simply alarming. Considering this from the patient’s perspective, how frightening must it be to know that if one of our nurses, doctors, or techs saw something wrong that could potentially cause us harm, there is an extremely high probability they would say nothing.

In spite of this reality, the great majority of our health care organizations have not sat idly by, observing all of this from the sideline. Training resources have been devoted to providing communication skills, national and local conferences bring in expert speakers to talk about strategies for improving teamwork, and internal studies have been conducted in the attempt to discover key actions health care providers can take to enhance team functioning.

A variety of assessments exist that serve to provide feedback to teams about their relationships, communication skills, and performance—examples include the TeamSTEPPS Team Perceptions Questionnaire (TPQ) (King et al. 2008), Relational Coordination (Hoffer Gittell 2002), and Five Dysfunctions of a Team (Lencioni 2002). Many other homegrown varieties also exist. The challenge with these assessments lies in interpreting and taking action in meaningful ways.

We have been involved in providing organizational team training for many years, and have witnessed firsthand how challenging it is to truly create a culture based on teamwork. Good intentions abound, everyone wants to be able to work in effective teams, but these underlying difficulties persist, even in the face of overwhelming data and stories that call out the negative consequences of poor and ineffective teamwork.

So if it is not a case of lack of caring, then what prevents us from having more effective teams? We believe it has to do with a lack of knowledge, understanding, and appreciation of the complexities present in today’s health care environment (Grol and Grimshaw 2003). We believe health care professionals need new models and frameworks that are more suited to the realities of today’s environment, and that can result in new practices.

At the center of all of this reside the leaders. And we are talking about leaders at all levels of health care, from administrators and medical directors to the nurse and clinic managers. Theirs is a difficult job, seemingly becoming more challenging every day as the health care environment shifts, especially in the technology, regulatory, scientific, and political arenas.

To address this challenge our goal is to provide physician, nurse, administrative, and other health care leaders with ideas, strategies, and tools to create and lead teams that have a learning orientation, have the ability to self-correct, and get exceptional results. We need to get health care leaders thinking differently about teams, to understand how they can create an environment where teaming thrives, and how they must lead to generate creativity and exceptional results.

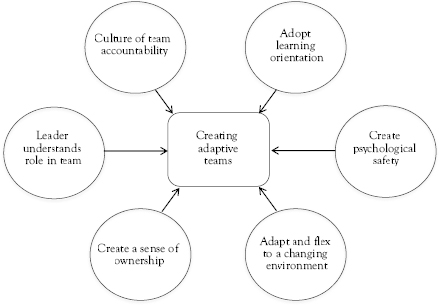

There are six specific topics we will address in this book:

1. Teams adopting a learning orientation

2. Creating a safe environment for practitioners to have a voice

3. The ability of teams to adapt and flex

4. Creating a sense of ownership within the team

5. Leader’s role in team: dealing with specific group dynamics

6. Creating ongoing accountability

Each of these topics (Figure 1.1) will be explored in-depth, and we will offer strategies that leaders can apply in very deliberate and concrete ways, so that the teams everyone so desperately want can actually exist.

Figure 1.1 A map for leading adaptive teams

End of Chapter Reflective Questions

• How would you describe the primary strengths of your team that contributes to excellent performance?

• What are the most pressing challenges facing your own team? What key factors are present?

• In what ways (and in what areas) does your team’s performance fall short of your expectations? What factors do you contribute to this?

References

2005 National Patient Safety Goals. 2005. Retrieved from www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/

Grol, R., and J. Grimshaw. 2003. “From Best Evidence to Best Practice: Effective Implementation of Change in Patients’ Care.” The Lancet 362, no. 9391, pp. 1225–30.

Hoffer Gittell, J. 2002. “Coordinating Mechanisms in Care Provider Groups: Relational Coordination as a Mediator and Input Uncertainty as a Moderator of Performance Effects.” Management Science 48, no. 11, pp. 1408–26.

King, H.B., J. Battles, D.P. Baker, A. Alonso, E. Salas, J. Webster, L. Toomey, and M. Salisbury. 2008. TeamSTEPPS™: Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety.

Lencioni, P. M. 2002. The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable, 13. John Wiley & Sons.

Maxfield, D. 2005. Silence Kills: The Seven Crucial Conversations for Healthcare. VitalSmarts.