Establishing a Sense of Urgency

Ask almost anyone over thirty about the difficulty of creating major change in an organization and the answer will probably include the equivalent of “very, very tough.” Yet most of us still don’t get it. We use the right words, but down deep we underestimate the enormity of the task, especially the first step: establishing a sense of urgency.

Whether taking a firm that is on its knees and restoring it to health, making an average contender the industry leader, or pushing a leader farther out front, the work requires great cooperation, initiative, and willingness to make sacrifices from many people. In an organization with 100 employees, at least two dozen must go far beyond the normal call of duty to produce a significant change. In a firm with 100,000 employees, the same might be required of 15,000 or more.

Establishing a sense of urgency is crucial to gaining needed cooperation. With complacency high, transformations usually go nowhere because few people are even interested in working on the change problem. With urgency low, it’s difficult to put together a group with enough power and credibility to guide the effort or to convince key individuals to spend the time necessary to create and communicate a change vision. In those rare circumstances in which a committed group does exist inside a canyon of complacency, its members may be able to identify the general direction for change, to reorganize, and to cut staffing levels. If these executives run a corporation, they might even make an acquisition and put in new compensation systems. But sooner or later, no matter how hard they push, no matter how much they threaten, if many others don’t feel the same sense of urgency, the momentum for change will probably die far short of the finish line. People will find a thousand ingenious ways to withhold cooperation from a process that they sincerely think is unnecessary or wrongheaded.

Complacency: An Example

A major global pharmaceuticals company has had more than its share of challenges over the past few years. Neither sales nor net income growth has kept up with prior hopes or expectations. The firm has gotten bad press, especially after a costly layoff that further eroded morale. The stock is not much higher today than it was six years ago. Complaints about its products are up compared with the mid-1980s, and one important customer has become increasingly negative. A few institutional investors have threatened to dump sizable holdings, an action that might send the stock price down another 5 or even 10 percent. The firm has a proud history and has had significant wins in the past, all of which makes the current situation look rather depressing.

Because the company is in a battle with tough competition, one might expect to find scenes at headquarters that are right out of a WW II vintage film, with war rooms, generals barking orders every two minutes, thousands of troops on twenty-four hour alert, and major assaults being directed on the enemy. But a visit to the company shows nothing of the sort. Visible war rooms don’t exist. Generals seem to give orders at a rate that makes baseball look like a fast-paced sport. Many people show no signs of being on alert for eight hours, much less twenty-four. There is little sense of enemy or that the competition is breathing down the company’s neck. There is no focus on a compelling mission. Assaults on rivals are often done with BB guns. More powerful shooting with more lethal weapons is aimed inward: workers at managers, managers at workers, sales at manufacturing, ad nauseam.

In one-on-one conversations with employees, everyone readily admits there are problems. Then come the “Buts.” But the whole industry is having these problems. But we really are making some progress. But the problem is not here, it’s over there in that department. But there is nothing else I can do because of my thickheaded boss.

Visit a typical management meeting at the company and you begin to wonder if all the facts you gathered about the firm’s revenues, income, stock price, customer complaints, competitive situation, and morale could have been wrong. In these meetings, reference is rarely made to any indexes of unacceptable performance. The pace is often leisurely. The issues discussed can be of marginal importance. The energy level is rarely high. Discussions become heated only when one manager tries to grab resources from another or to point the finger of blame elsewhere. And most incredibly, every once in a while you hear someone sincerely make a speech about how good things are.

After two days at the firm, you begin to wonder if you’ve entered the Twilight Zone.

In this complacency-filled organization, change initiatives are dead on arrival. Someone in a meeting suggests that long new-product development cycles are increasingly hurting the firm, but within twenty minutes the discussion has shifted elsewhere and no action is taken to begin shortening development times. Someone else offers a new approach to information technology, yet within a short time the IT group and its ancient system are being praised. Even when the CEO throws out an idea for change, the suggestion tends to sink in the quicksand of complacency.

If you think this story is irrelevant because nothing comparable happens in your organization, I strongly suggest that you look more closely. These conditions can be found almost everywhere. The credit department is a disaster, yet gives no signs of admitting that even a minor problem exists. The French subsidiary is a turnaround case, yet management there seems perfectly content with the current situation.

I cannot count the number of times I have heard an executive claim that all of the people on his or her management team recognize the need for major change only to discover myself that half of that “team” thinks the status quo isn’t really so bad. In public, they may parrot the boss’s line. In private, I hear a different story. “When the recession ends, we will be in good shape.” “As soon as last year’s cost-cutting programs kick in, the numbers will go up.” And, of course, “The bigger problems are over there; my department is fine.”

Q: How big a deal is this sort of complacency?

A: A huge deal.

Sources of Complacency

Q: So why do people behave this way?

A: For lots and lots and lots of reasons.

When I show twenty-five-year-old MBA students a company that is in trouble yet where complacency is high, they often talk as if the firm were being run by a group of people with an average IQ of forty. Their implicit diagnosis: If the place is in trouble yet urgency is low, then the management must be a bunch of dopes. Their action recommendation: Fire them and hire us.

The MBA student diagnosis linking ineptitude and complacency does not fit well with my experiences. On occasions I’ve seen inappropriately low senses of urgency among highly intelligent, well-intentioned people. I can still vividly remember sitting in a meeting of a dozen senior managers in a severely underperforming European corporation and listening to an intellectual debate that might have played well at Harvard. And why not? Many of the people around the table that day had degrees from the world’s best schools. Unfortunately, both the analysis of alleged competitor mistakes and the rather abstract discussion of “strategy” avoided confronting any of the firm’s key problems. Predictably, no decision of any consequence was made at the end of the meeting, since you can’t make important decisions without talking about the real issues. I’m sure that the typical person in that room that day was not very happy with the session. These were not fools. But they found the meeting acceptable because on an urgency scale of 0 to 100, the average rating among those executives was certainly less than 50.

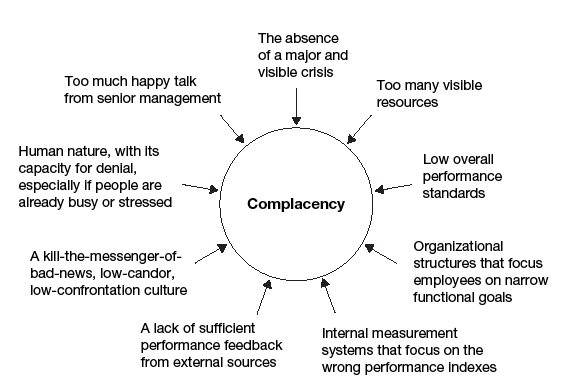

At least nine reasons help explain this sort of complacency (figure 3–1). First, no highly visible crisis existed. The firm was not losing money. No one had threatened a big layoff. Bankruptcy was not an issue. Raiders were not knocking at the door. The press was not serving up constantly negative headlines about the firm. As a rational analyst, you could argue that the company was in a crisis because of steadily declining market shares and margins, but that’s a different issue. The point here: Employees saw no tornado-like threat, which was one reason their sense of urgency was low.

FIGURE 3-1

Sources of complacency

Second, that meeting was taking place in a room that screamed “Success.” The thirty-foot antique mahogany table could have been traded evenly for three new Audis and a Buick. The wall fabrics, wool carpeting, and overall decor were as beautiful as they were expensive. The entire corporate headquarters, especially the executive area, was the same way: marble, rich woods, deep carpets, and oil paintings in abundance. The subliminal message was clear: we are rich, we are winners, we must be doing something right. So relax. Have lunch.

Third, the standards against which these managers measured themselves were far from high. Wandering around that firm, if I heard once, I heard ten times: “Profits are up 10 percent over last year.” What was not said was that profits were down 30 percent from five years before, and industrywide profits were up nearly 20 percent over the previous twelve months.

Fourth, the organizational structure focused most people’s attention on narrow functional goals instead of broad business performance. Marketing had its indexes, manufacturing had a different set, personnel yet another. Only the CEO was responsible for overall sales, net income, and return on equity. So when the most basic measures of corporate performance were going down, virtually no one felt responsible.

Fifth, the various internal planning and control systems were rigged to make it easy for everyone to meet their functional goals. People in the corporate marketing group told me they achieved 94 percent of their objectives during the previous year. A typical goal: “Launch a new ad campaign by June 15.” Increasing market share in any of the firm’s product lines was not deemed to be an appropriate target.

Sixth, whatever performance feedback people received came almost entirely from these faulty internal systems. Data from external stakeholders rarely went to anyone. The average manager or employee could work for a month and never be confronted with an unsatisfied customer, an angry stockholder, or a frustrated supplier. Some people could probably work from day one until retirement and never hear directly from an unhappy external stakeholder.

Seventh, when enterprising young employees went out of their way to collect external performance feedback, they were often treated like lepers. In that corporate culture, such behavior was seen as inappropriate because it might hurt someone, reduce morale, or lead to arguments (that is, honest discussions).

Eighth, complacency was supported by the very human tendency to deny that which we do not want to hear. Life is usually more pleasurable without problems and more difficult with them. Most of us, most of the time, think we have enough challenges to keep us busy. We are not looking for more work. So when evidence of a big problem appears, if we can get away with ignoring the information, we often will.

Ninth, those who were relatively unaffected by complacency sources 1–8 and thus concerned about the firm’s future were often lulled back into a false sense of security by senior management’s “happy talk.” “Sure, we have challenges, but look at all that we’ve accomplished.” People who were around during the 1960s will remember a terrifying example of this: the many reports of how the United States was winning the war in Vietnam. Although happy talk is sometimes insincere, it is often the product of an arrogant culture that, in turn, is the result of past success.

Much of the problem here is related to historical victories—for the firm as a whole, for departments, and for individuals. Past success provides too many resources, reduces our sense of urgency, and encourages us to turn inward. For individuals, it creates an ego problem; for firms, a cultural problem. Big egos and arrogant cultures reinforce the nine sources of complacency, which, taken together, can keep the urgency rate low even in an organization faced with major challenges and managed by perfectly intelligent and reasonable people.

I think we often assume that if only other individuals were more like us—strong and alert achievers—complacency would not be an issue. Or we think that the people are, for the most part, pretty smart, so all you have to do is give them the facts about poor product quality, sliding financial results, or lack of productivity growth. In both cases, we underestimate the power of the subtle and systemic forces that exist in virtually all organizations. A good rule of thumb in a major change effort is: Never underestimate the magnitude of the forces that reinforce complacency and that help maintain the status quo.

Pushing Up the Urgency Level

Increasing urgency demands that you remove sources of complacency or minimize their impact: for instance, eliminating such signs of excess as a big corporate air force; setting higher standards both formally in the planning process and informally in day-to-day interaction; changing internal measurement systems that focus on the wrong indexes; vastly increasing the amount of external performance feedback everyone gets; rewarding both honest talk in meetings and people who are willing to confront problems; and stopping baseless happy talk from the top.

When confronted with an organization that needs renewal, all competent managers take some of these actions. But they often do not go nearly far enough. A panel of customers is brought to the annual management meeting, but no way is found to bring customer complaints to everyone’s attention on a weekly or even daily basis. That annual management meeting might be held at a less posh place, but then executives go back to offices that even Louis XIV would not think shabby. One or two relatively frank discussions of problems are initiated at the executive committee level, but the company newspaper is allowed to be full of happy talk.

Creating a strong sense of urgency usually demands bold or even risky actions that we normally associate with good leadership. A few modest activities, like the customer panel at the annual management meeting, usually fail in the face of the overwhelmingly powerful forces fueling complacency. Bold means cleaning up the balance sheet and creating a huge loss for the quarter. Or selling corporate headquarters and moving into a building that looks more like a battle command center. Or telling all your businesses that they have twenty-four months to become first or second in their markets, with the penalty for failure being divestiture or closure. Or making 50 percent of the pay for the top ten officers based on tough product-quality targets for the whole organization. Or hiring consultants to gather and then force discussion of honest information at meetings, even though you know that such a strategy will upset some people greatly. (See table 3–1 for nine basic means of raising a sense of urgency.)

We don’t see these kinds of bold moves more often because people living in overmanaged and underled cultures are generally taught that such actions are not sensible. If those executives have been associated with an organization for a long time, they might also fear that they will be blamed for creating the very problems they spotlight. It is not a coincidence that transformations often start when a new person is placed in a key role, someone who does not have to defend his or her past actions.

TABLE 3-1

Ways to raise the urgency level

| 1. | Create a crisis by allowing a financial loss, exposing managers to major weaknesses vis-à-vis competitors, or allowing errors to blow up instead of being corrected at the last minute. |

| 2. | Eliminate obvious examples of excess (e.g., company-owned country club facilities, a large air force, gourmet executive dining rooms). |

| 3. | Set revenue, income, productivity, customer satisfaction, and cycle-time targets so high that they can’t be reached by conducting business as usual. |

| 4. | Stop measuring subunit performance based only on narrow functional goals. Insist that more people be held accountable for broader measures of business performance. |

| 5. | Send more data about customer satisfaction and financial performance to more employees, especially information that demonstrates weaknesses vis-à-vis the competition. |

| 6. | Insist that people talk regularly to unsatisfied customers, unhappy suppliers, and disgruntled shareholders. |

| 7. | Use consultants and other means to force more relevant data and honest discussion into management meetings. |

| 8. | Put more honest discussions of the firm’s problems in company newspapers and senior management speeches. Stop senior management “happy talk.” |

| 9. | Bombard people with information on future opportunities, on the wonderful rewards for capitalizing on those opportunities, and on the organization’s current inability to pursue those opportunities. |

For people who have been raised in a managerial culture where having everything under control was the central value, taking steps to push up the urgency level can be particularly difficult. Bold moves that reduce complacency tend to increase conflict and to create anxiety, at least at first. Real leaders take action because they have confidence that the forces unleashed can be directed to achieve important ends. But for someone who has been rewarded for thirty or forty years for being a cautious manager, initiatives to increase urgency levels often look too risky or just plain foolish.

If top management consists only of cautious managers, no one will push the urgency rate sufficiently high and a major transformation will never succeed. In such cases, boards of directors have a responsibility to find leaders and to place them in key jobs. If they duck that responsibility, as they sometimes do, they are failing to do the board’s most essential work.

The Role of Crises

Visible crises can be enormously helpful in catching people’s attention and pushing up urgency levels. Conducting business as usual is very difficult if the building seems to be on fire. But in an increasingly fast-moving world, waiting for a fire to break out is a dubious strategy. And in addition to catching people’s attention, a sudden fire can cause a lot of damage.

Because economic crises are so visible, major change is often said to be impossible until an organization’s problems become severe enough to generate significant losses. While this conclusion may be true in cases where a huge and difficult transformation is needed, I think it applies poorly to most situations that need change.

I have seen people successfully initiate restructurings or quality efforts during times when their firms were making record profits. They did so by relentlessly bombarding employees with information about problems (profits up but market share down), potential problems (a new competitor is showing signs of becoming more aggressive), or potential opportunities (through technology or new markets). They did so by setting vastly ambitious goals that disrupted the status quo. They did so by aggressively removing signs of excess, happy talk, misleading information systems, and more. Catching people’s attention during good times is far from easy, but it is possible.

One great Japanese entrepreneur regularly stopped his management from becoming complacent despite record earnings by setting outrageous five-year goals. Just when people would start to become smug over their many achievements, he’d say something like: “We should set a target of doubling our revenues within four years.” Because of his credibility, his employees couldn’t ignore these pronouncements. Because he never pulled the goals out of thin air, but instead put careful thought into what stretch objectives would be feasible given inspired effort, his ideas were always defendable. And in defending them, he tied the objectives back to basic values with which his management identified. The net result: His five-year goals became little bombs that periodically blew up pockets of complacency.

Real leaders often create these sorts of artificial crises rather than waiting for something to happen. Harry, for instance, instead of arguing with his managers’ plans, as was normally his style, decided to accept revenue and cost projections that he knew were unrealistic. The resulting 30 percent plunge in expected income caught everyone’s attention. In a similar manner, Helen accepted what she believed were unrealistic promises about a major new product introduction and allowed the whole thing to blow up in her face—not an action to be taken by the faint of heart. The result: Business as usual simply couldn’t continue.

Some artificial crises rely on large financial losses to wake people up. One CEO of a well-known corporation cleaned up a balance sheet, funded a number of new initiatives, and created a loss of nearly $1 billion in the process. But this was an unusual situation. The CEO had a long-term contract and the firm was awash in cash.

The problem with major financial crises, whether natural or rigged, is that they often drain scarce resources from the firm and thus leave less maneuvering room. After losing a billion or two, you can usually get people’s attention, but you end up with far fewer funds to support new initiatives. Even though transformations start more easily with a natural financial crisis, given a choice, it’s clearly smarter not to wait for one to happen. Better to create the problem yourself. Better still, if at all possible, help people see the opportunities or the crisislike nature of the situation without inducing crippling losses.

The Role of Middle and Lower-Level Managers

If the target of change is a plant, sales office, or work unit at the bottom of a larger organization, the key players will be those middle or lower-level managers who are in charge of that unit. They will need to reduce complacency and increase urgency. They will need to create a change coalition, develop a guiding vision, sell that vision to others, etc. If they have sufficient autonomy, they can often do so regardless of what is happening in the rest of the organization. If they have enough autonomy.

Without sufficient autonomy in a firm where complacency is rife (not an unusual situation today), a change effort in a small unit can be doomed from the start. Sooner or later the broader forces of inertia will intervene no matter what the lower-level change agents do. Under these circumstances, plunging ahead with a transformation effort can be a terrible mistake. When people realize this fact, they often think they have only one alternative: Sit back and wait for someone at the top to start providing strong leadership. So they do nothing, and in the process strengthen the very forces of inertia that so infuriate them.

Because they have the power, senior executives are usually the key players in reducing the forces of inertia. But not always. Occasionally a brave and competent soul at the middle or lower level in the hierarchy is instrumental in creating the conditions that can support a transformation.

My favorite example is a middle manager in a large travel-related services company who almost singlehandedly confronted top management with data on the firm’s increasingly fragile competitive position. She used a nonroutine assignment—to put a product through a new distribution channel—as an excuse to hire consultants. With her behind-the-scenes encouragement, the consultants basically said that the firm would never be able to use the new channel successfully unless it first dealt with a half-dozen fundamental problems. Her peers ran for cover when they saw the results of this work, but she plunged ahead. Because she had political savvy, she deflected most of the criticism created by denial and anger onto the consultants. She had this amazing capacity to serve up lines like: “This really surprised me. Did the consultants screw up or is there something important here?”; “I can’t believe that they sent the report to all those people. We didn’t authorize that”; “You believe this? So do Gerry and Alice. Have the three of you ever talked about these issues?”

If everyone in senior management is a cautious manager committed to the status quo, a brave revolutionary down below will always fail. But I have never seen an organization in which the entire top management is against change. Even in the worst cases, 20 to 30 percent seem to know that the enterprise isn’t living up to its potential, want to do something, but feel blocked. Middle-management initiatives can give these people the opportunity to attack complacency without being seen as poor team players or rabble rousers.

For those in middle management who cannot find a way to help push up the urgency level in a firm that needs change but in which senior management is not providing the necessary leadership, a smart career decision may be to move elsewhere. In today’s economic environment, people often cling to their jobs, even if their firms are going nowhere. They convince themselves that with all the downsizing they are lucky to have a paycheck and health-care benefits. This attitude is understandable. But in the world of the twenty-first century, we will all need to learn and grow throughout our careers. One of the many problems in complacent organizations is that rigidity and conservatism make learning difficult.

Punching a time clock, collecting a check, learning little, and allowing the urgency rate to remain low is at best a parochial and short-term strategy. Parochial and short-term strategies rarely lead to long-term success anymore, for either companies or their employees.

How Much Urgency Is Enough?

Regardless of how the process is started or by whom, most firms find it difficult to make much progress in phases 2–4 of a major change effort unless most managers honestly believe that the status quo is unacceptable. Sustaining a transformation effort in stages 7 and 8 demands an even greater commitment. A majority of employees, perhaps 75 percent of management overall, and virtually all of the top executives need to believe that considerable change is absolutely essential.

Because some initial movement is possible with low levels of urgency and because the assault on complacency may create anxiety, it can be tempting to skip stage 1 and begin the transformation process with a later step. I’ve seen people start by building the change coalition, by creating the change vision, or by simply making changes (reorganizing, laying off staff, making an acquisition). But the problems of inertia and complacency always seem to catch up with them. Sometimes they quickly hit a wall, as when a lack of urgency makes it impossible to put together a powerful enough leadership team to guide the changes. Sometimes people go for years—perhaps with an acquisition fueling growth and excitement—before it becomes apparent that various initiatives are flagging.

Even when people do begin major change efforts with complacency-reduction exercises, they sometimes convince themselves that the job is done when in fact more work is necessary. I have seen exceptionally capable individuals fall into this trap. They speak with fellow executives who only reinforce their rationalizations. “We’re all ready for this. Everyone understands that the current situation has to be changed. There’s not much complacency around here. Right Phil? Right Carol?” They move ahead on a shaky base and eventually come to regret it.

Outsiders can be helpful here. Ask well-informed customers, suppliers, or stockholders what they think. Is the urgency rate high enough? Is complacency low enough? Don’t just talk to fellow employees who have the same incentives as you to discount reality. And don’t ask these questions only of a few friends on the outside. Talk to others who know your firm or even to people who seem to be at odds with your organization. And, most important, muster up the courage to listen carefully.

If you do this, you will find that some people are not well enough informed to offer a credible judgment and that others have axes to grind. But you can sort all of this out if you talk to enough people. The point is to counteract insider myopia with external data. In a fast-moving world, insider myopia can be deadly.