When one of the most visionary, charismatic executives I’ve known was appointed president of a $1.7 billion division of a large U.S. company, the level of excitement at that business rose dramatically. To many employees, his first year felt like a wonderful and needed breath of fresh air. Suddenly, bold ideas were discussed in meetings instead of seeming trivialities. Sacred cows were herded away, and anyone with valid information on problems or opportunities was given a hearing. As a coalition of people emerged around the new leader, that team began talking of shifts in the fundamental strategic direction of the firm.

A vision of a global powerhouse began to emerge, a firm that would exploit new technologies to offer some basic, high-quality building materials at remarkably low prices. By the middle of year two, communication about the new vision permeated every part of the organization. By the beginning of year three, more and more changes were being made to help convert the vision into reality. New products were launched. New training programs were introduced. Departments were reorganized. A major reengineering effort was begun in the finance function. One key executive took an early retirement. Nearly $500 million was spent on a major acquisition. All the activity was exhilarating. Even the business press loved it; in the middle of year three, four different publications ran flattering articles about the changes being made at that firm.

This story impressed me greatly. Not that I didn’t see some red flags. Our hero’s guiding coalition was never linked very strongly to corporate headquarters. But so much of what he was doing was right on target that if you had asked me during year three, I would probably have said that this business would become the leader in its industry within the next forty-eight months. I couldn’t imagine that the transformation process could be derailed.

I was wrong.

To make a long story short, in the middle of year four, the charismatic leader was fired. Over the next twelve months, many of his initiatives collapsed and disappeared. During that time, probably two or three other managers were forced out of the firm, and at least a half-dozen more left on their own accord. Employee morale collapsed. Financial results actually improved for a few quarters before beginning a long march downward. As I write this, the division is still a mess.

With the benefit of hindsight, the errors are easy to spot. Only one executive at corporate headquarters was a part of the guiding coalition, and he wasn’t a particularly influential individual. By the middle of year two, people who disagreed with that coalition were ignored, even if they were trying to be helpful. But the worst mistake was that insufficient attention was given to short-term results. People became so caught up in big dreams that they didn’t effectively manage the current reality. When critics asked for evidence that all this activity was moving the firm in the right direction, despite few if any performance improvements, nothing convincing was offered. When the coalition accused the disgruntled of being a bunch of unvisionary poops, corporate headquarters grew wary. When the division missed almost all of its financial projections in year three by a small amount, without warning corporate much in advance, the CEO grew wary. When the division lost money in the second quarter of year four, again without much warning, the charismatic division president was fired.

Some people both inside and outside of this company still think the CEO made a terrible mistake. They could be right. But the charismatic division general manager unquestionably made one major error. By putting almost no emphasis on short-term results, he didn’t build the credibility he needed to sustain his efforts over the long haul.

Major change takes time, sometimes lots of time. Zealous believers will often stay the course no matter what happens. Most of the rest of us expect to see convincing evidence that all the effort is paying off. Nonbelievers have even higher standards of proof. They want to see clear data indicating that the changes are working and that the change process isn’t absorbing so many resources in the short term as to endanger the organization.

Running a transformation effort without serious attention to short-term wins is extremely risky (see figure 8–1). Sometimes you get lucky; visible results just happen. But sometimes your luck runs out, as it did for the visionary division general manager.

The Usefulness of Short-Term Wins: An Example

An insurance company has a huge reengineering effort under way. Aware that the project will take at least four years to complete, those on the guiding coalition ask themselves, How can we target and then produce some unambiguous performance improvements in six to eighteen months? With careful thought, they identify three areas: one department in which costs could drop significantly within a year, a process improvement that should be quickly visible to and liked by customers, and a small reorganization that should improve morale in one group. For each of the three areas, specific goals and plans are built into the company’s two-year operating budget. One person in the coalition is given responsibility for monitoring all three efforts. In executive committee meetings, at least once every sixty days all three miniprojects are reviewed.

FIGURE 8-1

The influence of short-term wins on business transformation

Case #1: No short-term wins

Case #2: Short-term wins at about fourteen months, but none a year later

Case #3: Short-term wins at fourteen and twenty-six months

Realizing these performance improvements within the short-term time frame turns out to be a challenge. Middle management tries to delay the reorganization. Even the zealots driving the reengineering effort want to slow down the process improvements that would be visible to customers. Complicating all this, the company’s information systems do not always track the correct data on which improvements can be shown. Had someone not actively managed these performance issues, the firm in this case would probably never have had three unambiguous short-term wins. Various pressures would have caused delays or changed the agenda. Existing systems would have failed to track the data needed to demonstrate the gains clearly.

Even with these wins, skeptics were able to find some evidence that the reengineering was too costly, too slow, or simply wrongheaded. But the performance improvements knocked air out of their sails. Creating those wins also provided the guiding coalition with concrete feedback about the validity of their vision. And for those who were working so hard to produce meaningful change, planning for the short-term results provided milestones they could look forward to while achieving the actual wins gave them a chance to pat themselves on the back.

The Nature and Timing of Short-Term Wins

The kind of results required in stage 6 of a transformation process are both visible and unambiguous. Subtlety won’t help. Close calls don’t either.

Having a good meeting usually doesn’t qualify as the kind of unambiguous win needed in this phase, nor does getting two people to stop fighting, producing a new design that the engineering manager thinks is terrific, or sending 5,000 copies of a new vision statement around the company. Any of these actions may be important, but none is a good example of a short-term win.

A good short-term win has at least these three characteristics:

1. It’s visible; large numbers of people can see for themselves whether the result is real or just hype.

2. It’s unambiguous; there can be little argument over the call.

3. It’s clearly related to the change effort.

When a reengineering effort promises that the first cost reductions will come in twelve months and they occur as predicted, that’s a win. When a reorganization early in a transformation reduces the first phase of the new-product development cycle from ten to three months, that’s a win. When the early assimilation of an acquisition is handled so well that Business Week writes a complimentary story, that’s a win.

In small companies or in small units of enterprises, the first results are often needed in half a year. In big organizations, some unambiguous wins are required by eighteen months. Regardless of size, this means that you’re probably still not out of most of the early stages when phase 6 has to produce something.

Q: But isn’t operating in multiple stages at once complicated?

A: Yes. But that’s what happens in successful cases of major change.

The Role of Short-Term Wins

Short-term performance improvements help transformations in at least six ways (as summarized in table 8–1). First, they give the effort needed reinforcement. They show people that the sacrifices are paying off, that they are getting stronger.

TABLE 8-1

The role of short-term wins

| • | Provide evidence that sacrifices are worth it: Wins greatly help justify the short-term costs involved. |

| • | Reward change agents with a pat on the back: After a lot of hard work, positive feedback builds morale and motivation. |

| • | Help fine-tune vision and strategies: Short-term wins give the guiding coalition concrete data on the viability of their ideas. |

| • | Undermine cynics and self-serving resisters: Clear improvements in performance make it difficult for people to block needed change. |

| • | Keep bosses on board: Provides those higher in the hierarchy with evidence that the transformation is on track. |

| • | Build momentum: Turns neutrals into supporters, reluctant supporters into active helpers, etc. |

Second, for those driving the change, these little wins offer an opportunity to relax for a few minutes and celebrate. Constant tension for long periods of time is not healthy for people. The little celebration following a win can be good for the body and spirit.

Third, the process of producing short-term wins can help a guiding coalition test its vision against concrete conditions. What is learned in these tests can be extremely valuable. Sometimes the vision isn’t entirely right. More often, the strategies need some adjustments. Without the concentrated effort to produce short-term wins, such problems can become apparent far too late in the game.

Fourth, quick performance improvements undermine the efforts of cynics and major league resisters. Wins don’t necessarily quiet all of these people (which is probably good, since diversity of opinion can keep a firm from blindly walking off a cliff), but they take some of the ammunition out of opponents’ hands and make it much more difficult to take cheap shots at those trying to implement needed changes. As a general rule, the more cynics and resisters, the more important are short-term wins.

Fifth, visible results help retain the essential support of bosses. From middle management all the way up to the board of directors, if those hierarchically above a transformation effort lose faith, it’s in deep trouble.

Finally, and perhaps most generally, short-term wins help build necessary momentum. Fence sitters are transformed into supporters, reluctant supporters into active participants, and so on. This momentum is critical, because, as we’ll see in the next chapter, the energy needed to complete stage 7 is often enormous.

Planning versus Praying for Results

Transformations sometimes go off track because people simply don’t appreciate the role that quick performance improvements play in a change effort. But more often the effort is undermined because managers don’t systematically plan for the creation of shortterm wins.

“So what kind of evidence do you think we’ll see within twenty-four months that all this is on track?” I ask.

“There are four or five possibilities,” a member of the guiding coalition replies.

“Possibilities?” I say.

“Yes. With a little luck, costs will be significantly down in either the order processing areas or the order fulfillment group.”

“A little luck,” I say.

“If marketing can get its act together fast enough, we might see some real revenue increases by then because of the new niching strategies.”

“You might?”

“Yes. And it’s possible, I suppose, that the new ad agency—we’re selecting one now—will have implemented enough of the TV strategy to show some measurable market share improvement.”

“It’s possible?”

“Yes, any of that might happen.”

In highly successful change efforts, you don’t hear much dialogue like this. Short-term wins don’t come about as the result of a little luck. They aren’t merely possibilities. People don’t just hope and pray for performance improvements. They plan for short-term wins, organize accordingly, and implement the plan to make things happen. The whole point is not to maximize short-term results at the expense of the future. The point is to make sure that visible results lend sufficient credibility to the transformation effort.

Q: Sounds obvious. So why doesn’t everyone do it?

A: For at least three reasons.

First, people don’t plan sufficiently for these wins because they are overwhelmed. Often the urgency rate hasn’t been pushed high enough, or the vision isn’t clear. As a result, the transformation isn’t going well and people are scrambling to somehow set things right. With all the panic, planning for short-term wins doesn’t receive sufficient time or attention.

In other cases, people don’t even try very hard to produce these wins because they believe you can’t produce major change and achieve excellent short-term results. Thousands and thousands of managers have been taught that life in organizations is a trade-off between the short run and the long run. In this belief system, you can focus long and take your lumps now or you can do well now and throw the future up for grabs. According to this line of thinking, undertaking a major change program means looking to the long term, which in turn means expecting short-term results to be problematic. Sure, you still need to pay attention to the immediate future, but you can’t plan for great results. It’s just not possible.

Ten years ago I might have agreed with this point of view. But I’ve seen too much recent evidence that contradicts it. In the words of a renowned executive: “The job of management is to win in the short term while making sure you’re in an even stronger position to win in the future.” In the past decade, I’ve watched dozens of firms have it both ways. They transformed themselves into better organizations for the future and they produced good results quarter by quarter.

A third element that undermines the planning for necessary wins is lack of sufficient management, especially on the guiding coalition, or a lack of commitment by key managers to the change process. To a large degree, leadership deals with the long term and management with the immediate future. Without enough good management, the planning, organizing, and controlling for results will not be sufficient.

Without competent management, inadequate thought is usually given to the whole question of measurement. So existing information systems either fail to record important performance improvements or underestimate their size. Without competent management, tactical choices are glossed over or implemented poorly. Acquisitions are made more on the basis of impulse instead of rational support of the vision. Sequencing of events—do we do the restructuring this year or after the quality effort is farther along—doesn’t get sufficient attention.

Because of all of the emphasis on management in the twentieth century, most organizations—with the exception of small, young firms—rarely lack this perspective. Up to a point, small firms can get away without much planning or control. If the company founder is a visionary who dislikes structure (not an unusual situation), he or she may resist the encroachment of managerial thinking, which can then prove to be a problem in this stage of a change effort.

In larger and older firms, the problem of insufficient management is typically associated with either a new strong leader who ignores his managers or a lack of commitment from those managers to the transformation. The former was true in the case of the charismatic division general manager who eventually lost his job. Deep in his heart, he thought people who kept the current system operating were of limited importance. He’d never actually say that, but you could read it between the lines. So when some of those people tried to advise him about short-term economic matters, he often ignored them.

A lack of commitment to change from managers in big, old organizations is often found when the early stages of a transformation are not handled well. With no sense of urgency, a lack of key managers on the guiding coalition, the failure to communicate an effective vision well, and little effort put into broad-based employee empowerment, people in overmanaged and underled organizations sit on the sidelines during change, especially managers who could be instrumental in producing needed short-term results.

More Pressure Isn’t All Bad

Targeting short-term wins during a transformation effort does increase the pressures on people. The argument is sometimes made that these extra demands are inappropriate. “We’ve got enough going on,” people say, “without more burdens. Give us a break.”

This way of thinking is not without merit. But more often than not, I’ve found that short-term pressure can be a useful way to keep up the urgency rate. A year or two into a major change program, with the end still not in sight, people naturally tend to let up. They begin to think: “If this is going to require four more years, a slide to four and a quarter won’t hurt.” But as soon as the urgency rate goes down, everything becomes much harder to accomplish. Minor tasks that were completed in a month suddenly take three times as long.

Of course, pressure doesn’t always produce urgency. The burden of producing short-term wins can create only stress and exhaustion. In successful change efforts, executives link pressure to urgency through the constant articulation of vision and strategies. “This is what we are trying to do and this is why it is so important. Without these short-term wins, we could lose everything. All that we want to do for our customers, shareholders, employees, and communities becomes problematic. So we have got to produce these results.” This kind of communication gives meaning to hardships and spurs people on. Twelve to thirty-six months into a major change effort, tired employees often need renewed motivation.

Short-Term Wins Aren’t Short-Term Gimmicks

To some degree, all management is manipulation—and that includes the production of short-term performance improvements. But in a few cases I’ve seen this manipulation taken to new heights, with increased potential for both good and harm.

To keep momentum building in a massive change effort, Phil becomes an accounting magician. He amortizes this, depreciates that, squeezes this group hard, and sells off a few assets. The net result is a bottom line that goes up slowly but steadily each quarter. Anytime people criticize his change program, he thrusts the net income data in their faces much as a fearless vampire killer uses a cross. And the strategy works, at least for a while.

Accounting wizardry of this sort can be helpful in certain difficult situations. But the risks involved are substantial. First, it can be addictive. Once you start this game, stopping can be difficult. Shortterm gimmicks can produce problems in the future that often can be covered up only with more short-term gimmicks. Second, it can create more cynics and resisters among the key executives who are sophisticated enough to see what is really happening. Powerful cynics can be very disruptive. Third, it can alienate people who see the practice as unethical.

Some of the downside risk can be eliminated if the entire guiding coalition discusses and agrees to the use of these methods. But even then, contrived results rarely provide a strong enough base on which to build further change in stages 7 and 8. Short-term wins that support transformation are usually genuine. They aren’t the product of smoke and mirrors.

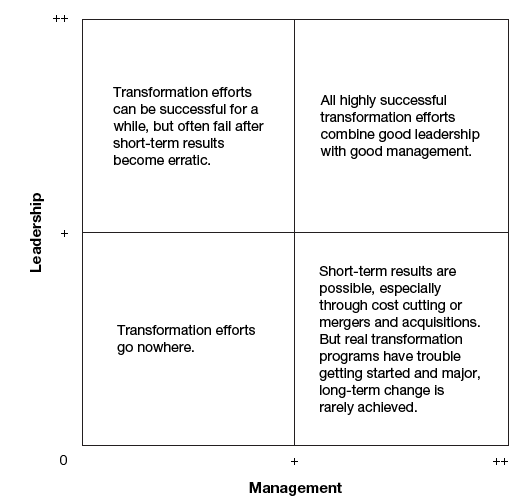

The Role of Management

Systematically targeting objectives and budgeting for them, creating plans to achieve those objectives, organizing for implementation, and then controlling the process to keep it on track—this is the essence of management. With that in mind, one can easily see that the need to create short-term wins in a successful change effort demonstrates an important principle: Transformation is not a process involving leadership alone; good management is also essential. A balance of the two is required, as shown in figure 8–2.

Because leaders are so central to any major change effort, we sometimes conclude that transformation equals leadership. Certainly without strong and capable leadership from many people, restructurings, turnarounds, and cultural changes don’t happen well or at all. But more is involved. Restructuring usually calls for financial expertise, reengineering for technical knowledge, acquisitions for strategic insight. And the process in all major change projects must be managed to keep the operation from lurching out of control or off a cliff.

FIGURE 8-2

The relationship of leadership, management, short-term results, and successful transformation

Q: But isn’t the need for management kind of obvious?

A: Generally, yes, but not necessarily to the type of charismatic leaders who sometimes launch transformations.

Charismatic leaders are often poor managers, yet they have a way of convincing us that all we need to do is follow them. “Don’t worry about the mundane details; just keep the vision in mind.” “Don’t concern yourself much with the financials; they will work out fine long term.” Our intellect is usually skeptical of this kind of approach, but our hearts can be won over nevertheless.

I’m not suggesting that charisma is bad. The best evidence says that personal appeal can be extremely helpful in a change effort. But when a charismatic leader is not a good manager and doesn’t value management skill in others, achieving short-term wins will be problematic at best. As a result, the credibility and momentum typically required to complete stage 7 of a successful transformation are rarely present. As we will see in the next chapter, the magnitude of change in stage 7 is often huge. Alterations of that scale and scope are never made without a solid foundation of credibility and powerful movement forward.

In a way, the primary purpose of the first six phases of the transformation process is to build up sufficient momentum to blast through the dysfunctional granite walls found in so many organizations. When we ignore any of these steps, we put all our efforts at risk.

In enterprises that have been around for decades, the granite walls can be thick. Sometimes, extremely thick.