Empowering Employees for Broad-Based Action

“If I hear the word empowerment one more time,” someone recently told me, “I think I’ll gag.” He was expressing exasperation at the fact that the more this increasingly popular term is used, the less it seems to mean. “It’s become a politically correct mantra,” he said. “Empower, empower, empower. I ask people what they mean by that and they either become inarticulate or they look at me like I’m an idiot.”

A few years ago, I might have agreed with his reservations. Today, I don’t. I’m still not enthusiastic about using faddish words, but in this ever faster-moving world, I think the idea of helping more people to become more powerful is important.

Environmental change demands organizational change. Major internal transformation rarely happens unless many people assist. Yet employees generally won’t help, or can’t help, if they feel relatively powerless. Hence the relevance of empowerment.

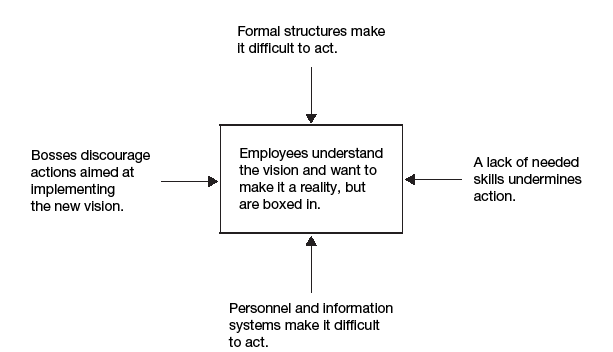

FIGURE 7-1

Barriers to empowerment

Effectively completing stages 1 through 4 of the transformation process already does a great deal to empower people. But even when urgency is high, a guiding coalition has created an appropriate vision, and the vision has been well communicated, numerous obstacles can still stop employees from creating needed change. The purpose of stage 5 is to empower a broad base of people to take action by removing as many barriers to the implementation of the change vision as possible at this point in the process.

What are the biggest obstacles that often need to be attacked? Four can be particularly important: structures, skills, systems, and supervisors (see figure 7–1).

Removing Structural Barriers

The firm in this case is a financial services organization in Australia. A new president pushes up the urgency rate, assembles a guiding coalition at the top, and helps it develop a new direction for the company that is centered around superior customer service. The basic concept is simple: to develop a capability that will not just gain share in Australia but that will allow the firm to compete effectively in emerging markets throughout Asia. The team’s success in communicating the new vision leaves many employees convinced that the firm is on the right path. When top management sees the enthusiastic response to its initiatives, its members conclude that the most difficult part of the transformation process may be over—which is probably why they take their collective eye off the ball.

Twenty-four months later, a frustrated and angry group of senior managers tries to assess what went wrong. They felt they had been doing their part. They had been visiting customers throughout the region, helping set up new systems to measure customer satisfaction, making speeches inside the firm to reinforce the customer service message, and working with consultants to redesign products and services to better meet marketplace requirements. But for some reason, the once enthusiastic troops just aren’t delivering.

A postmortem finds the following. Many employees really did want to provide superior products and services, and they tried. But the organizational structure so fragmented resources and authority that delivering well any of the new financial products was nearly impossible. A typical product required people from four different functional organizations to work together seamlessly. Even when employees tried to create cross-functional teams that were product/customer focused, they found the process enormously frustrating. Strong structural silos undermined the teams in dozens of subtle ways, making the timely delivery of new services to customers virtually impossible. When employees complained to their supervisors, they were told that they should try to be better team players. When they suggested that perhaps the organizational structure was a problem, they were given a dozen excuses about why changing the structure was not possible, or wouldn’t help, or would take a long time. Disempowered, they gave up trying to implement the new vision.

When the CEO in this case confronted his managers with the structural problem and asked for their advice, they told him:

1. implementation of the new vision was a complicated affair,

2. they might have the wrong kind of employee, which would take a very long time to correct,

3. middle management was exhausted after putting in long hours trying to do the right thing, and

4. there was no obvious solution to these problems.

To some degree, all of this was true. Long workweeks were common, for example, but key people in middle management were also stressed out from trying to preserve their functional fiefdoms despite mounting evidence that a reorganization would be necessary to deliver the new products and services. As is so often the case with change, resistance didn’t come from everyone. Only a few managers were really dragging their feet. But they were difficult to influence, partly because they had convinced themselves that they were doing the right thing for the company.

Colin was typical of the footdraggers. After twenty-five years of experience, he well understood the virtues of the functional organization in which he had invested so much time and energy. The various schemes for reorganization not only broke up his group and greatly reduced the size of his job, they also eliminated some of the business benefits of the traditional structure. Had Colin completely embraced the new vision, he would have reluctantly had to agree that losses from a restructuring were not that significant. But he saw the vision as a pleasant dream with about a one-in-four chance of being realized. So with the losses clear and certain and the potential gains foggy and improbable, he dragged his feet. The net result was that the company retained an organization structure that systematically blocked employee efforts to implement the new vision.

Structure is not always a big barrier in transformations, at least in the early stages, but I’ve seen many cases in which organizational arrangements undermine a vision by disempowering people (as listed in table 7–1). The case of the Australian financial services firm is not uncommon. Customer-focused visions often fail unless customer-unfocused organizational structures are modified. Another typical example would be an electrical utility whose vision of frontline employees taking on much more responsibility bumps up against a structure with too many levels and too much decision-making authority vested in the middle. As employees try to make the new vision a reality, their decisions are second-guessed and undermined by a hoard of middle managers. “Did you take this into consideration?” “You should have checked with Jones first.” “Do you realize the precedent you might be setting?” Predictably, after a while, most frontline employees give up and revert back to their old ways of operating.

TABLE 7-1

How structure can undermine vision

| The vision | The structure |

| • Focus on the customer | • But the organization fragments resources and responsibility for products and services |

| • Give more responsibility to lower-level employees | • But there are layers of middle-level managers who second-guess and criticize employees |

| • Increase productivity to become the low-cost producer | • But huge staff groups at corporate headquaters are expensive and constantly initiate costly procedures and programs |

| • Speed everything up | • But independent silos don’t communicate and thus slow everything down |

Whenever structural barriers are not removed in a timely way, the risk is that employees will become so frustrated that they will sour on the entire transformational effort. If that happens, even if you eventually reorganize correctly, you’ve lost the energy needed to use the new structure to make the vision a reality.

Why does this happen? Sometimes we become so accustomed to one basic organizational design, perhaps because it has been used for decades, that we are blind to the alternatives. Sometimes people have so much invested in one structure, in terms of personal loyalties and functional expertise, that they are afraid of the potential career consequences. Sometimes senior managers know a redesign is needed, but they don’t want to get into a fight with middle management or with their peers. But often the basis for change hasn’t been firmly enough established. Middle management easily resists structural change when it doesn’t feel a sense of urgency, doesn’t see a dedicated team at the top, doesn’t see a sensible vision for change, or doesn’t feel that others believe in that vision.

Providing Needed Training

Nearly twenty years ago I watched a forward-thinking automotive parts company try to make major changes in its manufacturing operations in order to leapfrog the competition. Long before others were taking layers out of middle management and giving more authority to lower-level employees, this firm had a vision of how such an approach could improve quality and lower costs. The guiding coalition made many mistakes, as pioneers always do, but successfully built a plant in the rural Southeast that was thin on middle management, largely run by teams of workers, and clearly ahead of its time. Getting the factory up and running was not easy, but no one was surprised by that. After reaching about 70 percent of the daily output target, plant management assumed the hard work was over. It wasn’t.

Output leveled off at 75 percent of target, an economically unacceptable result. The workforce became increasingly grumpy. Fights actually broke out in one of the manufacturing teams. Managers who had been skeptical about the experiment began to wonder out loud if “workers” could really handle “managerial” responsibility. A few disgruntled employees began listening to union overtures. Someone at corporate headquarters suggested that they “pull the plug” on this new method of operation before events spun out of control.

As is so often the case, a few people in the factory had correctly diagnosed the problem, but others weren’t listening to them. The plant manager eventually talked to nearly everyone and then decided that a junior employee-relations specialist had the best explanation for why they were stuck at 75 percent. In essence, that young man said:

We have taken 200 people, managers and workers, and put them into a situation that is different from anything they had experienced before. All of them, especially the older ones, have some habits built up over years that are no longer relevant, sometimes even dysfunctional. Many of our workers have learned relatively sophisticated skills associated with ducking responsibility. None of them know much about operating effectively in teams in a work setting. Most of our managers have been taught by five to thirty-five years of experience that their job is to make decisions, not empower others. The amount of training we received to cope with this new situation seems, in retrospect, woefully inadequate. Because most of us wanted very much to make the new plant successful, we worked exceptionally hard during start-up. In a way, we used sheer effort to make up for lack of skills. But that’s not a long-term solution. We got tired, and then frustrated.

Today this problem is often seen in major reengineering efforts. Training is provided, but it’s not enough, or it’s not the right kind, or it’s not done at the right time. People are expected to change habits built up over years or decades with only five days of education. People are taught technical skills but not the social skills or attitudes needed to make the new arrangements work. People are given a course before they start their new jobs, but aren’t provided with follow-up to help them with problems they encounter while performing those jobs.

I think there are two common reasons why we fall into this trap. First, we often don’t think through carefully enough what new behavior, skills, and attitudes will be needed when major changes are initiated. As a result, we don’t recognize the kind and amount of training that will be required to help people learn those new behaviors, skills, and attitudes. Second, we sometimes do recognize correctly what is needed, but when we translate that into time and money, we are overwhelmed by the results. How can anyone justify sending 10,000 people to a two-day training course? Or spend $3 million on a special educational effort?

Two of the most successful transformations in the world in the mid-1980s involved European airlines that did send tens of thousands of people to two-day training sessions and that did spend millions of dollars in the process. In both cases, the companies were pursuing new customer-first visions. In both cases, the guiding coalitions concluded that important attitudinal changes were needed to implement the visions and strategies. The two-day course, exceptionally well designed by a Danish consulting firm, was not meant to be a one-shot panacea for all the behavioral, skill-related, and attitudinal problems. Instead, a series of lectures and exercises simply demonstrated how behavior that “put people first” paid off greatly in life, both on and off the job. All the evidence I’ve seen strongly suggests that this training was a critical element in empowering employees to put the new visions to work. And both airlines emerged from the process as much stronger and more successful competitors.

As in the case of the airlines, attitude training is often just as important as skills training. Over the past century, millions of nonmanagerial employees have been taught by their companies and their unions not to accept much responsibility. For many of these people, you can’t just say, “OK, now you’re empowered, go to it.” Some simply won’t believe you, some will think it’s an exploitative trick, and others will worry that they aren’t capable. New experiences are needed to erase corrosive beliefs, and some of that can be done efficiently with training.

I see no evidence that all organizations should spend millions on education during attempts at major change. In some cases, big training budgets are unnecessary because large numbers of people are not being asked to learn significantly new skills, behaviors, or attitudes. In many cases, clever design of educational experiences can deliver greater impact at one-half or less the cost of conventional approaches. I also think that training can easily become a disempowering experience if the implicit message is “shut up and do it this way” instead of “we will be delegating more, so we are providing this course to help you with your new responsibilities.”

The point is: Some training could be required at this stage in a transformation, but it needs to be the right kind of experience. Throwing money at the problem is never a good idea, nor is talking down to people.

Aligning Systems to the Vision

“We’ve done everything,” one manager tells me, “but they just keep resisting.”

“OK,” I say, “tell me more.”

“We’ve worked enormously hard to develop an exciting concept for what we want to become. We’ve communicated those ideas endlessly through every mechanism we could think of. We reorganized last year to make the structure consistent with the new concept. Where necessary, we’ve retrained people. All this has demanded great time and energy, but we’ve done it.”

“So what’s the problem?”

“Far too many people are still conducting business the old way,” he complains.

“Why do you think that is?”

“I’m beginning to suspect that it’s just human nature to resist change.”

“If you won the lottery for $10 million,” I ask, “would you refuse to accept the money?”

“Are you kidding?”

“But there is plenty of evidence that when people win a lot of money their lives change in some pretty important ways.”

“So?”

“So you’re telling me you wouldn’t resist that change.”

“OK, OK,” he says. “So maybe people don’t resist all kinds of change.”

“When don’t they resist?”

“I suppose if they see it’s in their best interests.”

“And do your HR systems make it in people’s best interests to implement your new vision?”

“HR systems?”

“Performance appraisal. Compensation. Promotions. Succession planning. Are they aligned with the new vision?”

“Well, maybe not entirely.”

Examination of this firm’s human resource systems reveals:

• The performance evaluation form has virtually nothing about customers on it, yet that is at the core of the new vision.

• Compensation decisions are based much more on not making mistakes than on creating useful change.

• Promotion decisions are made in a highly subjective way and seem to have at best a limited relationship to the change effort.

• Recruiting and hiring systems are a decade old and only marginally support the transformation.

Further investigation also shows that management information systems haven’t changed much to help the transformation; likewise the strategic planning process, which still focuses much too much on short-term financial information and much too little on market/competitive analysis.

During the first half of a major change effort, owing to constraints on time, energy, and/or money, you can’t alter everything. Barriers associated with the organization’s culture, for example, are extremely difficult to remove completely until the end of each change project, after performance improvements are clear. Systems are easier to move, but if you tried to iron out every little inconsistency between the new vision and the current systems, you’d simply fail. Before some solid short-term wins are established, the guiding coalition rarely has the momentum or power to make that much change. Nevertheless, when the big, built-in, hard-wired incentives and processes are seriously at odds with the new vision, you must deal with that fact directly. Dodging the issue disempowers employees and risks undermining the change.

Q: How often do the systems, especially the HR systems, get in the way?

A: Far too often.

History often leaves HR people in highly bureaucratic personnel functions that discourage leadership and make altering human resource practices a big challenge. Breaking out of this pattern is not easy. Yet in successful transformations, I increasingly see gutsy HR men and women helping provide the leadership needed to change the systems to fit a new vision. In some cases they do so despite little encouragement from line managers or even from their HR colleagues. They do so because they care deeply about employees and are appalled by the consequences of poorly handled change efforts.

Dealing with Troublesome Supervisors

Frank doesn’t seem to get it. He’s been told a dozen times that the company is trying to become more innovative because creativity is paying off greatly in its industry. But he refuses to change a command-and-control style that snuffs out initiative and creativity as quickly as carbon dioxide kills a fire. Watching him operate, you might wonder if he didn’t get a degree in disempowerment. “We’ve tried that before,” he says again and again. “You need to do more analysis on the downside possibilities,” he tells his people. “We don’t have time for that, just do this please.” “Yeah, yeah, that’s very interesting, but . . . No, no, don’t send that report around; people don’t need that information.” “Please Martha, next time check with me first before you do anything.”

Frank runs a department with about a hundred employees. Waves of change wash up to his door, break, and then retreat out to sea. A few of his people try to support the corporate renewal program despite Frank’s best efforts. But most don’t. Some tried initially and then gave up. Some, like Frank, just don’t get it. Others are cautious and political and take their cue from the boss.

Change zealots tend to demonize Frank, but he’s not really a bad person. To a large degree, like all of us, he’s a product of his history. He learned a command-and-control style early on, and because that behavior seemed to work and help him get ahead in the company, it developed into a deeply ingrained set of habits.

If Frank’s problem were related to only a single discrete element, change would come much more easily. But that’s not the case. He has dozens of interrelated habits that add up to a style of management. If he alters just one aspect of his behavior, all the other interrelated elements tend to put great pressure on him to switch that one piece of behavior back to the way it was. What he needs is to change all the habits as a group, but that can feel as hard as trying to quit smoking, drinking, and eating fatty foods all at the same time.

The fact that Frank doesn’t entirely believe in the new “innovation” vision makes all this even more difficult, as does the fact that he’s not entirely sure what he would need to do to help implement that vision. And, like all of us, he’s skilled at rationalizing the situation so that, in his own eyes, he looks like the good corporate citizen while others are political, self-serving, or incompetent.

People like Frank seem to exist in all cases of reengineering, restructuring, or strategic change. If there are enough of them, or if they are in charge of enough employees, they can be a huge problem. If particularly powerful people like Frank are not confronted early in a change process, they can undermine the entire effort.

I’ve seen at least a dozen cases where three or four key players were Frank-like. Instead of confronting the problem, an enthusiastic change agent and a few colleagues dragged those people through stages 1 to 4 of a transformation. But in stage 5, the refusal of these supervisors to let go and empower their employees finally brought a strained effort to a halt.

One major reason why the Franks of the world aren’t confronted is that others are afraid that these people can’t change, yet they are unwilling to demote or fire them. Sometimes the unwillingness to act is driven by guilt, especially if the disempowerers are friends or former mentors. Political considerations also play a big role in these cases. People fear that if a fight erupts, the Franks may be powerful enough to win, perhaps even forcing the change agents out. In many other situations, the reluctance to act is related to the good short-term results delivered by people like Frank.

Easy solutions to this sort of problem often don’t exist. Faced with that reality, managers sometimes concoct incredibly complicated political strategies. They try to manipulate the Franks into a corner where they can be contained or killed off. The problem with such an approach is that it is often slow, and if exposed to daylight it can look terrible—sleazy, cruel, unfair.

From what I’ve seen, the best solution to this kind of problem is usually honest dialogue. Here’s the story with the industry, the company, our vision, the assistance we need from you, and the time frame in which we need all this. What can we do to help you help us? If the situation really is hopeless, and the person needs to be replaced, that fact often becomes clear early in this dialogue. If the person wants to help but feels blocked, the discussion can identify solutions. If the person wants to help but is incapable of doing so, the clearer expectations and timetable can eventually make his or her removal less contentious. The basic fairness of this approach helps overcome guilt. The rational and thoughtful dialogue also helps minimize the risk that good short-term results will suddenly turn bad or that Frank and others like him will be able to launch a successful political counterattack.

Guilt, political considerations, and concerns over short-term results stop people all the time from having these honest discussions. In retrospect, executives often express regret that they didn’t confront problem managers sooner in the process. If I’ve heard it once, I’ve heard it a hundred times: “I should have dealt with Hal/George/Irene much earlier.”

An unwillingness to confront managers like Frank is common in change efforts. It rarely helps. These blockers stop needed action. Perhaps even more important, others see that these people are not being confronted and they become discouraged. Discouraged employees do not produce the short-term wins that are vital to building momentum in a transformation effort. Discouraged employees do not help manage the large number of change projects that typically are needed in a transformation. Instead, they give up long before you have reached the finish line and anchored new approaches in the organization’s culture.

Tapping an Enormous Source of Power

Discouraged and disempowered employees never make enterprises winners in a globalizing economic environment. But with the right structure, training, systems, and supervisors to build on a well-communicated vision (see table 7–2), increasing numbers of firms are finding that they can tap an enormous source of power to improve organizational performance. They can mobilize hundreds or thousands of people to help provide leadership to produce needed changes.

TABLE 7-2

Empowering people to effect change

| • | Communicate a sensible vision to employees: If employees have a shared sense of purpose, it will be easier to initiate actions to achieve that purpose. |

| • | Make structures compatible with the vision: Unaligned structures block needed action. |

| • | Provide the training employees need: Without the right skills and attitudes, people feel disempowered. |

| • | Align information and personnel systems to the vision: Unaligned systems also block needed action. |

| • | Confront supervisors who undercut needed change: Nothing disempowers people the way a bad boss can. |