Consolidating Gains and Producing More Change

When people registered for the annual management meeting, they were given a packet of materials that included a compilation of favorable press clippings from the prior twelve months. At the opening banquet, the CEO praised the 110 executives for all they had accomplished and ended the night with four toasts. During the first full day of the meeting, no fewer than six speakers identified recent achievements and saluted the audience. That night, an awards banquet gave plaques to fifteen people. The next morning, presentations on “best practices” dissolved into more back patting. In the evening, a famous singer entertained the group. If all that didn’t send egos into deep space, the final congratulatory speech by the CEO did.

Whatever sense of urgency that had existed at the senior management level died at that meeting. The implicit message was loud and clear. We can handle this tough market environment. Piece of cake. Look at all we’ve accomplished recently. We’re in great shape. So relax and enjoy the music.

Of course no one actually said, “Relax,” and the CEO was very much aware that much more was required to complete a transformation started a few years earlier. All he was trying to do was thank his executives and motivate them with sincere praise. But the message received by the audience was that the difficult work of change was behind them.

During the next year, a dozen change initiatives at that firm were put on hold or slowed down. A consultant’s recommendation for a major reorganization in one division was shelved. The third phase in a reengineering effort in another division was temporarily delayed. Suddenly people began having second thoughts about agreed-on alterations in corporate personnel practices. The investment bankers who were trying to divest one business were told to take a rest. Issues identified earlier and marked for action during that year were mostly ignored. By the time key change agents in top management fully realized what was happening, much of the momentum built up after three years of hard work was lost.

Major change often takes a long time, especially in big organizations. Many forces can stall the process far short of the finish line: turnover of key change agents, sheer exhaustion on the part of leaders, bad luck. Under these circumstances, short-term wins are essential to keep momentum going, but the celebration of those wins can be lethal if urgency is lost. With complacency up, the forces of tradition can sweep back in with remarkable force and speed.

Resistance: Always Waiting to Reassert Itself

Irrational and political resistance to change never fully dissipates. Even if you’re successful in the early stages of a transformation, you often don’t win over the self-centered manager who is appalled when a reorganization encroaches on his turf, or the narrowly focused engineer who can’t fathom why you want to spend so much time worrying about customers, or the stone-hearted finance executive who thinks empowering employees is ridiculous. You can drive these people underground or into the tall grass. But instead of changing or leaving, they will often sit there waiting for an opportunity to make a comeback. In celebrating short-term wins, change agents can give the opposition just that opportunity.

Sometimes the resisters actually organize the celebration, especially if they are shrewd and cynical. After a hyperventilated meeting, they give voice to the implicit message. I guess that proves we have won, they say. The sacrifices were significant, but we did accomplish something. Now let’s all take a deserved breather. If people really are weary, they will be inclined to listen, even if they know that much has yet to be done. They rationalize that a little rest and stability won’t hurt. Maybe a vacation will put us in better shape for the next phase.

The consequences of a mistake here can be extremely serious. After watching dozens of major change efforts in the past decade, I’m confident of one cardinal rule: Whenever you let up before the job is done, critical momentum can be lost and regression may follow. Until changed practices attain a new equilibrium and have been driven into the culture, they can be very fragile. Three years of work can come undone with remarkable speed. Once regression begins, rebuilding momentum can be a daunting task, not unlike asking people to throw their bodies in front of a huge boulder that has already begun to roll back down the hill. All but change zealots will recoil from this request. Under these circumstances, the human capacity to rationalize is amazing: “I’ve done my share; now it’s Juan’s turn.” “Maybe we went too far; maybe a little regression is good.”

Progress can slip quickly for two reasons. One has to do with corporate culture, and I’ll talk more about that in the next chapter. The second is directly related to the kind of increased interdependence that is created by a fast-moving environment, interconnections that make it difficult to change anything without changing everything.

The Problem of Interdependence

All organizations are made up of interdependent parts. What happens in the sales department has some effect on the manufacturing group. R&D’s work influences product development. Engineering specifications affect manufacturing. The amount of interdependence, however, can vary greatly among organizations depending on a number of factors, none of which is more important than the competitiveness of the business environment.

In the kind of benign oligopolistic world that existed in many major industries for much of the twentieth century, the relatively stable and prosperous environment allowed organizations to minimize internal interdependence. Large in-process inventories buffered various sections of a plant and provided each with some autonomy. Large finished-goods inventories protected manufacturing from actions in the sales department. A slow and linear product development process allowed engineering, sales, marketing, and manufacturing some degree of independence. The lack of better transportation and communication options gave the Malaysian operation considerable freedom from headquarters in New York.

This way of running a business is disappearing for a number of reasons, particularly because of increased competition. With the exception of a few monopolies, organizations cannot now afford big inventories, slow and linear product development, and a foreign operation that goes its own way. Now and in the foreseeable future, most organizations need to be faster, less costly, and more customer focused. As a result, internal interdependencies will grow. Firms are finding that without big inventories, the various parts of a plant need to be much more carefully coordinated, that with pressure to bring out new products faster, the elements of product development need much closer integration, and so on. But these new interconnections greatly complicate transformation efforts, because change happens much more easily in a system of independent parts.

Imagine walking into an office and not liking the way it is arranged. So you move one chair to the left. You put a few books on the credenza. You get a hammer and rehang a painting. All this may take an hour at most, since the task is relatively straightforward. Indeed, creating change in any system of independent parts is usually not difficult.

Now imagine going into another office where a series of ropes, big rubber bands, and steel cables connect the objects to one another. First, you’d have trouble even walking into the room without getting tangled up. After making your way slowly over to the chair, you try to move it, but find that this lightweight piece of furniture won’t budge. Straining harder, you do move the chair a few inches, but then you notice that a dozen books have been pulled off the bookshelf and that the sofa has also moved slightly in a direction you don’t like. You slowly work your way over to the sofa and try to push it back into the right spot, which turns out to be incredibly difficult. After thirty minutes, you succeed, but now a lamp has been pulled off the edge of the desk and is precariously hanging in midair, supported by a cable going in one direction and a rope going in the other.

Organizations are coming to look more and more like this bizarre office. Few things move easily, because nearly every element is connected to many other elements. You ask Mary to do something in a new way. Nothing happens. You ask again. She budges an inch. You put pressure on her. Maybe you get two inches. You become furious at Mary, making all sorts of unkind inferences about her character and motivation. But the main problem is that, just like the chair and sofa, a dozen different forces are holding Mary’s behavior in place. In her case, instead of ropes and cables and rubber bands you find supervisors, organizational structures, performance appraisal systems, personal habits, cultures, peer relationships, and (most important) an ongoing stream of demands from this group and that department and those people.

Under these circumstances, convincing Mary to behave in new ways can be very difficult. Getting a thousand more employees like her to approach their work differently can be a monumental undertaking.

The Nature of Change in Highly Interdependent Systems

Most of our direct personal experience with successful change is like the first, real-life office example. The chair isn’t in the right place, so we move it. Few if any of us grew up learning how to introduce major change in highly interdependent systems. That, in turn, makes the challenge in organizations today more difficult.

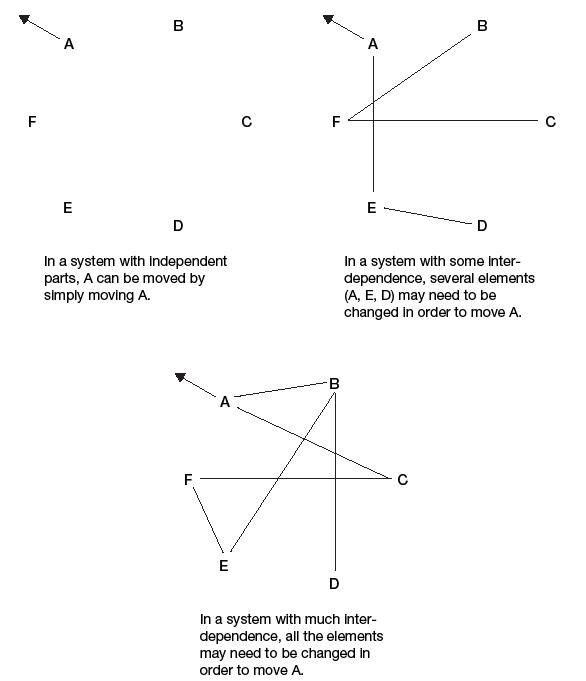

Without much experience, we often don’t adequately appreciate a crucial fact: that changing highly interdependent settings is extremely difficult because, ultimately, you have to change nearly everything (see figure 9–1). Because of all the interconnections, you can rarely move just one element by itself. You have to move dozens or hundreds or thousands of elements, which is difficult and time consuming and can rarely if ever be accomplished by just a few people.

Even in the relatively simple case of the interconnected office, interdependencies can seriously complicate change. For example: Let’s say we want to make some shifts in a dozen of those offices so the spaces will be more pleasant for visiting customers. We’re going to move lamps closer to sofas so clients can read brochures more easily. We’re going to switch the chair behind the desk with the less comfortable chair that sits beside the sofas. We’re going to take a few pieces of written material that customers always want to see and put them on the coffee tables in front of the sofas. In a dozen real-life offices, where everything is pretty much independent, these changes could be made by one person in an hour or two. In offices strung with ropes, cables, and rubber bands, these changes would require much more time and effort.

FIGURE 9-1

Creating change in systems of varying interdependence

So what do you do? If you haven’t had much experience with this kind of situation, you’ll go find one or two others, ask or order them to help, and then go to work. But after a few frustrating hours in which little is accomplished, your helpers will be looking for any possible excuse to jump ship. Word will then spread quickly about your little change project. Someone who is zealous about helping customers may volunteer to help. But most people will dive for cover when they see you coming down the hall.

If you’ve had experience with this kind of change, you’ll know that you need to slow down at first to build up the capacity to deal successfully with the situation. Your initial question will be: Is the urgency rate, especially around the issue of helping customers, high enough around here? If the honest answer, confirmed by external sources, is yes, you move ahead. If the answer is no, then the question becomes: How can I reduce complacency and increase urgency?

If you haven’t had a lot of experience with changing interdependent systems, you’ll probably become pretty impatient pretty fast. “This is ridiculous,” you’ll say. “I could spend days or weeks trying to push urgency up among this crowd. I don’t have that kind of time.” So you grab two people and start ordering them to. . . .

Experienced change agents know how to direct their impatience. In this situation, soon after beginning to work on complacency regarding customers, they might take the first steps in putting together a team to guide the project. If the urgency level is at rock bottom, even that won’t be possible, because no one will sign up to help. So they may begin trying to clarify the vision of the new office space, all the time placing first priority on lowering complacency.

In this simple case, you may need only one or two other people for your change coalition. The three of you will clarify the overall vision for the effort and calculate strategies for bringing it to life. You’ll find ways to communicate this information to the 20 or 50 or 100 other people who have some stake in the situation and its outcome. You’ll identify those factors that will hamper implementation of the vision and try to deal with the more serious items on the list. And then, and only then, you’ll begin to put together a plan for moving the furniture, to enlist help, and to start working on the offices.

Because this change project is relatively small, indeed trivial compared with retooling a big company, all this activity may take only a few weeks (unless complacency is very high). But to any of your colleagues who have had little experience introducing major change to highly interdependent systems and who have the impulse to grab two others and finish the job in one afternoon, the few weeks of activity will seem like a long time.

Once you get started on the room, you’ll probably proceed in a series of projects, not just one big move. You’ll discover some sequencing issues; you can’t move the desk chair until you first do something else. If you’re smart, you’ll program in a few short-term wins to keep up group morale. Even with the wins, halfway through this little effort some people will begin to wonder if these changes are really necessary. Surely customers can read without the extra light. The chair by the sofa isn’t so bad. Customers can walk; let them go over to the bookcase themselves and get the written material.

If you’re really dedicated to fixing up the rooms, you’ll find a number of methods to keep the process going. You’ll locate a few people who are good at moving furniture in this kind of situation and bring them on board. You’ll find newly relevant ways to talk about the overall purpose of the activity so that the communication of the vision doesn’t grow stale.

If you don’t give up, you’ll probably add other projects later in the effort. As you get more and more familiar with all the cables and ropes, you’ll discover that some of them seem to serve no useful purpose, and you’ll try to get rid of them. Most of the ropes and rubber bands may go easily. The wire cables will prove to be more difficult. You’ll also begin to have additional ideas about how you can make life even better for visiting customers. Why not lower the blinds a bit to keep the sun out of their eyes? Instead of making new projects out of each of these ideas, you’ll find opportunistic ways to address the issues within currently planned work. Sometimes you’ll be successful, sometimes not.

The net effect: You’ll end up making more changes than you imagined at first. The entire effort will take more time and energy than you initially expected. One piece of good news is that you’ll probably be in a better position to do something similar in the future, because you have both acquired skills and disconnected some of the useless wires and cables. And, of course, in the end, the office will be more customer friendly.

Organizational Transformations

The process of introducing change to an organization is not that different from rearranging the furniture in that group of offices. A lot of people need to help. You never have a complete sense of all the changes at the beginning. The warm-up steps take a surprising amount of time and energy. The action eventually occurs in a series of projects. As the magnitude of the effort becomes clear, you will be tempted to give up. If you stay the course, the total time involved will be lengthy.

The first major performance improvement will probably come well before the halfway point. Although some people will want to quit then, in successful transformations the guiding coalition uses the credibility afforded by the short-term win to push forward faster, tackling even more or bigger projects. The restructuring that was avoided early on because of all the resistance is finally undertaken. Two new reengineering projects, both of which were conceived at the beginning of the transformation, are launched. A total reworking of the strategic planning process is finally scheduled. But to restructure, reengineer, and change strategic planning, you find that you also have to alter training programs, modify information systems, add or subtract staff, and introduce new performance appraisal systems. Before long, dozens of elements in the interdependent whole are targeted for action.

People raised in managerial positions during the 1950s and 1960s often can’t imagine how ten or twenty change projects can exist simultaneously. But that is precisely what happens in stage 7 of a major transformation.

Q: How can executives manage twenty change projects all at once?

A: They can’t. In successful transformations, executives lead the overall effort and leave most of the managerial work and the leadership of specific activities to their subordinates.

Firms that try to juggle twenty change projects today by using the methods that successful companies applied to the same problem three decades ago always seem to fail. No matter how good the people involved, the process simply does not work. Executives end up with sixteen-hour days in endless meetings trying to deal with conflicts and coordination problems, yet even that doesn’t overcome a constant string of delays.

The process fails for two interrelated sets of reasons. First, the management approach back then was usually too centralized to handle twenty complex change projects. If a few senior managers try to get involved in all the details, as was often the practice then, everything slows to a crawl. Second, without the guiding vision and alignment that only leadership can provide, the people in charge of each of the projects wind up spending endless hours trying to coordinate their efforts so that they aren’t constantly stepping on each other’s toes.

Running twenty change projects simultaneously is possible if (a) senior executives focus mostly on the overall leadership tasks and (b) senior executives delegate responsibility for management and more detailed leadership as low as possible in the organization. In this approach, not ten (or a hundred) but a hundred (or a thousand) people are available to help with the twenty projects. More important, the leadership provided by senior executives helps give those other people the information they need to help coordinate their activities without endless planning and meetings.

Imagine two situations. In the first, competent leadership is lacking at the top, and as a result the people trying to run change projects haven’t a clue as to what the organization’s overall vision is or how their projects fit into that vision. They know only that they are supposed to cut costs in engineering overhead by 20 percent, or reengineer the way parts come into the plant, or redesign the succession planning process. As they try to complete their projects, they find themselves constantly in conflict with two dozen other efforts. No, you can’t do it that way, they are told, because that will screw us up. No, I need those resources today; why didn’t you inform me about your plans weeks ago? Senior managers try to mediate all the conflicts and set rational priorities, but they simply do not have the time. All this leads to frustration, a growing number of meetings, a political tug of war, and eventually some degree of chaos.

In the second situation, good leadership from above helps everyone understand the big picture, the overall vision and strategies, and the way each project fits into the whole. Here the people working on different activities all aim for the same long-term goal without ever having to meet much. They can also anticipate where conflicts with the other projects might develop, where the priorities should be in light of the overall vision, and what they should do to help move the company forward. Within this framework, conflicts are managed at lower levels in the organization by people who have the time and relevant information. With good leadership from above, these lower-level managers will also be committed to the overall transformation and will thus do what is right with a minimum of parochial political silliness.

With sufficient leadership from above and lots of delegation of both management and leadership activities, twenty change projects can be run simultaneously. If either element is missing, those twenty projects will create chaos, and stage 7 of a major transformation may collapse.

Elimination of Unnecessary Interdependencies

Because internal interconnections make change so difficult, somewhere during this stage of a major transformation effort people begin to raise questions about the need for all the interdependence. They ask: Why should the plant manager have to send report K2A to the finance people at corporate headquarters once a month? Does finance really need that data? Do they need it monthly? Does the plant have to create the report? Why do divisions have to check with corporate HR before making any job offer over $50,000? Does corporate HR need to be involved? If a legitimate reason exists, is $50,000 too low a cutoff point?

This kind of questioning usually escalates when people become angry at the difficulty of producing needed change in highly interdependent systems. If channeled properly, these inquiries can be extremely helpful. All organizations have some unnecessary interdependencies that are the product of history instead of the current reality. Sales can’t do something without manufacturing’s approval because of a crisis that occurred in 1954, which led to that policy. Cleaning up historical artifacts does create an even longer change agenda, which an exhausted organization will not like. But the purging of unnecessary interconnections can ultimately make a transformation much easier. And in a world where change is increasingly the norm rather than the exception, cleaning house can also make all future reorganizing efforts or strategic shifts less difficult.

A Long Road

Because changing anything of significance in highly interdependent systems often means changing nearly everything, business transformation can become a huge exercise that plays itself out over years, not months. At the extreme, stage 7 can become a decade-long process in which hundreds or thousands of people help lead and manage dozens of change projects. The qualities characterizing stage 7 are listed in table 9–1.

Here, again, is where leadership is invaluable. Outstanding leaders are willing to think long term. Decades or even centuries can be meaningful time frames. Driven by compelling visions that they find personally relevant, they are willing to stay the course to accomplish objectives that are often psychologically important to them. While others shift jobs every two years, leaders will sit in a junior position for twice as long or in a senior position for more than a decade. Instead of declaring victory and giving up or moving on, they will launch the dozen change projects often required in stage 7 of a transformation. They will also take the time to ensure that all the new practices are firmly grounded in the organization’s culture.

TABLE 9-1

What stage 7 looks like in a successful, major change effort

| • | More change, not less: The guiding coalition uses the credibility afforded by short-term wins to tackle additional and bigger change projects. |

| • | More help: Additional people are brought in, promoted, and developed to help with all the changes. |

| • | Leadership from senior management: Senior people focus on maintaining clarity of shared purpose for the overall effort and keeping urgency levels up. |

| • | Project management and leadership from below: Lower ranks in the hierarchy both provide leadership for specific projects and manage those projects. |

| • | Reduction of unnecessary interdependencies: To make change easier in both the short and long term, managers identify unnecessary interdependencies and eliminate them. |

Because of the nature of management processes, managers often think in terms of much shorter time frames. For them, the short term is this week, the medium term a few months, the long term a year. With that time horizon, announcing victory and stopping change after twenty-four or thirty-six months seems logical. To people who have had a managerial mindset pounded into them for decades, three years can seem like avery, very long time.

Again: Without sufficient leadership, change stalls, and excelling in a rapidly changing world becomes problematic.