Leadership and Lifelong Learning

The key to creating and sustaining the kind of successful twenty-first-century organization described in chapter 11 is leadership—not only at the top of the hierarchy, with a capital L, but also in a more modest sense (l) throughout the enterprise. This means that over the next few decades we will see both a new form of organization emerge to cope with faster-moving and more competitive environments and a new kind of employee, at least in successful firms.

The twenty-first-century employee will need to know more about both leadership and management than did his or her twentieth-century counterpart. The twenty-first-century manager will need to know much about leadership. With these skills, the type of “learning organization” discussed in chapter 11 can be built and maintained. Without these skills, dynamic adaptive enterprises are not possible.

For those raised on traditional notions about leadership, this idea makes no sense. In the most commonly known historical model, leadership is the province of the chosen few. Within that framework, the concept of masses of people helping to provide the leadership needed to drive the eight-stage change process is at best foolhardy. Even if you think you reject the old model, if you have lived on planet earth during the twentieth century this highly elitist notion is likely buried somewhere in your head and may affect your actions in ways invisible to you.

The single biggest error in the traditional model is related to its assumptions about the origins of leadership. Stated simply, the historically dominant concept takes leadership skills as a divine gift of birth, a gift granted to a small number of people. Although I, too, once believed this, I have found that the traditional idea simply does not fit well with what I have observed in nearly thirty years of studying organizations and the people who run them. In particular, the older model is nearly oblivious to the power and the potential of lifelong learning.

A Prototype of the Twenty-First-Century Executive

I first met Manny in 1986. At that time, he was an alert, friendly, and ambitious forty-year-old manager. He had already done well in his career, but nothing about him seemed exceptional. No one in his firm, at least as much as I could tell, called him “a leader.” I found him to be a little cautious and somewhat political, like many people raised in twentieth-century bureaucracies. I would have expected him to remain in a senior staff job for a few decades and to make a useful but far from outstanding contribution to his corporation.

The second time I met Manny was in 1995. In only a short conversation, I could sense a depth and sophistication that had been unapparent before. In talking with others at his company, again and again I heard a similar assessment. “Isn’t it amazing how much Manny has grown,” they told me. “Yes,” I said, “it’s amazing.”

Today Manny is running a business that will generate about $600 million in after-tax profits. That business is rapidly globalizing with all the attendant hazards and opportunities. As I write this, he is leading his group through a major transformation designed to position the organization for a promising future. All from a man who did not look like a leader, much less a great leader, at age forty.

A few people like Manny have always been around. Instead of slowing down and peaking at age thirty-five or forty-five, they keep learning at a rate we normally associate only with children and young adults. These exceptions to the norm help us see that nothing inherent in human DNA prevents growth later in life. The biography that I’m now completing of Japanese industrialist Konosuke Matsushita, one of the twentieth century’s most remarkable business leaders, shows this tendency in an extreme form. Descriptions of Matsushita early in life tell us of a hard-working but sickly young man. Nowhere are terms such as brilliant, dynamic, visionary, or charismatic used to describe him then, much less leader. Yet he grew to be an entrepreneur during his twenties, a business leader in his thirties and forties, and a major-league organizational transformer in his fifties. As a result, he helped his firm rebound after the horrors of World War II, absorb new technology, expand globally, and renew itself again and again so as to succeed beyond anyone’s dreams. He then took on additional successful careers as a writer in his sixties, a philanthropist in his seventies, and an educator in his eighties.

In the twenty-first century, I think we will see more of these remarkable leaders who develop their skills through lifelong learning, because that pattern of growth is increasingly being rewarded by a rapidly changing environment. In a static world, we can learn virtually everything we need to know in life by the time we are fifteen, and few of us are called on to provide leadership. In an ever changing world, we can never learn it all, even if we keep growing into our nineties, and the development of leadership skills becomes relevant to an ever-increasing number of people.

As the rate of change increases, the willingness and ability to keep developing become central to career success for individuals and to economic success for organizations. People like Manny or Matsushita often do not begin the race with the most money or intelligence, but they win nevertheless because they outgrow their rivals. They develop the capacity to handle a complex and changing business environment. They grow to become unusually competent in advancing organizational transformation. They learn to be leaders.

The Value of Competitive Capacity

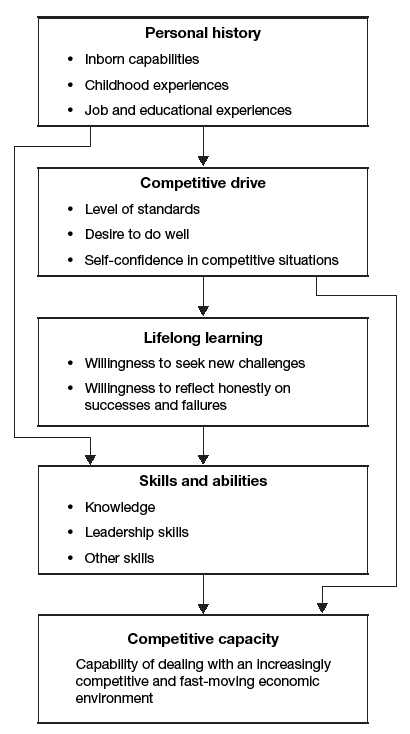

The importance of lifelong learning in an increasingly changing business environment and its relationship to leadership was demonstrated rather dramatically in a twenty-year study of 115 students from the Harvard Business School class of 1974. In attempting to explain why most were doing well in their careers despite the challenging economic climate that took shape at about the time they graduated, I found that two elements stood out: competitive drive and lifelong learning. These factors seemed to give people an edge by creating an unusually strong competitive capacity (see figure 12–1). Competitive drive helped create lifelong learning, which kept increasing skill and knowledge levels, especially leadership skills, which in turn produced a prodigious ability to deal with an increasingly difficult and fast-moving global economy. Like Manny, people with high standards and a strong willingness to learn became measurably stronger and more able leaders at age fifty than they had been at age forty.

FIGURE 12-1

The relationship of lifelong learning, leadership skills, and the capacity to succeed in the future

Source: From The New Rules: How to Succeed in Today’s Post-Corporate World by John P. Kotter. Copyright © 1995 by John P. Kotter. Adapted with permission of The Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster.

Marcel DePaul was typical of this group. He grew up in a middle-class family and attended a good but not outstanding university in Michigan. He was admitted to the MBA program based less on test scores than on an impressive track record both in and out of high school. By age thirty-five, he was doing well in his career, but no one was predicting great accomplishments. As a staff officer in a large, European-based manufacturing firm, he had a good but not great reputation. When I interviewed him in 1982, the word leader never occurred to me. A dozen years later, the story had changed greatly.

By 1994, Marcel was the head of his own company, had hundreds of employees, and was very wealthy. He had invented a product and a market and had built an organization to capitalize on both. Within his world, he was known as a “visionary.” One person with whom I talked went on and on about Marcel’s “charisma.” All this from a guy that didn’t much impress me in 1982.

In attempting to explain Marcel’s success, I think we are all inclined to look for lucky breaks, and good fortune certainly can be found in his case. But one can also see a difficult business environment that served up plenty of bad luck and hardship. What is striking about Marcel’s story is how the bad times didn’t wear him down but instead served as a source of learning and growth.

When hit with an unexpected downturn, he would often become angry or morose, but he would never give up or let defensiveness paralyze him. He reflected on good times and bad, and tried to learn from both. Confronting his mistakes, he minimized the arrogant attitudes that often accompany success. With a relatively humble view of himself, he watched more closely and listened more carefully than did most others. As he learned, he relentlessly tested new ideas, even if that meant pushing himself out of his zone of comfort or taking some personal risks.

Listening with an open mind, trying new things, reflecting honestly on successes and failures—none of this requires a high IQ, an MBA degree, or a privileged background. Yet remarkably few people behave in these ways today, especially after age thirty-five and especially when they are already doing well in their careers. But by using these relatively simple techniques, Marcel, Manny, Matsushita, and people like them keep growing while others level off or decline. As a result, they become more and more comfortable with change, they actualize whatever leadership potential they possess, and they help their firms adapt to a rapidly shifting global economy.

The Power of Compounded Growth

If you study the Marcels, Mannys, and Matsushitas of the world, you find that the secret to their capacity to develop leadership and other skills is closely related to the power of compounded growth.

Consider this simple example. Between age thirty and fifty, Fran “grows” at the rate of 6 percent—that is, every year she expands her career-relevant skills and knowledge by 6 percent. Her twin sister, Janice, has exactly the same intelligence, skills, and information at age thirty, but during the next twenty years she grows at only 1 percent per year. Perhaps Janice becomes smug and complacent after early successes. Or maybe Fran has some experience that sets a fire underneath her. The question here is, how much difference will this relatively small learning differential make by age fifty?

Given the facts about Fran and Janice, it’s clear that the former will be able to do more at age fifty than the latter. But most of us underestimate how much more capable Fran will become. The confusion surrounds the effect of compounding. Just as we often don’t realize the difference over twenty years between a bank account earning 7 percent versus 4 percent, we regularly underestimate the effects of learning differentials.

For Fran and Janice, the difference between a 6 percent and a 1 percent growth rate over twenty years is huge. If they each have 100 units of career-related capability at age thirty, twenty years later, Janice will have 122 units, while Fran will have 321. Peers at age thirty, the two will be in totally different leagues at age fifty.

If the world of the twenty-first century were going to be stable, regulated, and prosperous, sort of like the 1950s and 1960s in the United States, then differential growth rates would be of only modest relevance. In that world, while Fran would likely be considered more accomplished than her sister, both would do just fine. Stability, regulation, and prosperity would reduce competition along with the need for growth, leadership skills, and transformation. But that’s not what the future holds.

Just as organizations are going to be forced to learn, change, and constantly reinvent themselves in the twenty-first century, so will increasing numbers of individuals. Lifelong learning and the leadership skills that can be developed through it were relevant to only a small percentage of the population until recently. That percentage will undoubtedly grow over the next few decades.

Habits of the Lifelong Learner

So how do the Frans and Mannys do it? Not with rocket science. The habits they develop are relatively simple (as summarized in table 12–1).

Lifelong learners take risks. Much more than others, these men and women push themselves out of their comfort zones and try new ideas. While most of us become set in our ways, they keep experimenting.

Risk taking inevitably produces both bigger successes and bigger failures. Much more than most of us, lifelong learners humbly and honestly reflect on their experiences to educate themselves. They don’t sweep failure under the rug or examine it from a defensive position that undermines their ability to make rational conclusions.

TABLE 12-1

Mental habits that support lifelong learning

| • | Risk taking: Willingness to push oneself out of comfort zones |

| • | Humble self-reflection: Honest assessment of successes and failures, especially the latter |

| • | Solicitation of opinions: Aggressive collection of information and ideas from others |

| • | Careful listening: Propensity to listen to others |

| • | Openness to new ideas: Willingness to view life with an open mind |

Lifelong learners actively solicit opinions and ideas from others. They don’t make the assumption that they know it all or that most other people have little to contribute. Just the opposite, they believe that with the right approach, they can learn from anyone under almost any circumstance.

Much more than the average person, lifelong learners also listen carefully, and they do so with an open mind. They don’t assume that listening will produce big ideas or important information very often. Quite the contrary. But they know that careful listening will help give them accurate feedback on the effect of their actions. And without honest feedback, learning becomes almost impossible.

Q: But these habits are so simple. Why don’t more of us develop them?

A: Because in the short term, it’s more painful.

Risk taking brings failure as well as success. Honest reflection, listening, solicitation of opinions, and openness bring bad news and negative feedback as well as interesting ideas. In the short term, life is generally more pleasant without failure and negative feedback.

Lifelong learners overcome a natural human tendency to shy away from or abandon habits that produce short-term pain. By surviving difficult experiences, they build up a certain immunity to hardship. With clarity of thought, they come to realize the importance of both these habits and lifelong learning. But most of all, their goals and aspirations facilitate the development of humility, openness, willingness to take risks, and the capacity to listen.

The very best lifelong learners and leaders I’ve known seem to have high standards, ambitious goals, and a real sense of mission in their lives. Such goals and aspirations spur them on, put their accomplishments in a humbling perspective, and help them endure the short-term pain associated with growth. Sometimes this sense of mission is developed early in life, sometimes later in adulthood, often a combination of the two. Whatever the case, their aspirations help keep them from sliding into a comfortable, safe routine characterized by little sensible risk taking, a relatively closed mind, a minimum of reaching out, and little listening.

Just as a challenging vision can help an organization to adapt to shifting conditions, nothing seems to support the habits that promote personal growth more than ambitious, humanistic goals.

Twenty-First-Century Careers

The more volatile economic environment, along with the need for more leadership and lifelong learning, is also producing careers that look quite different from those typical of the twentieth century.

Most of the successful white-collar workers in the past hundred years found reputable companies to work for early in their lives and then moved up narrow functional hierarchies while learning the art of management. Most successful blue-collar workers found companies with good unions, learned how to do a certain job, and then stayed in that position for decades. In the twenty-first century, neither of these career paths will provide many people with a good life because neither encourages sufficient lifelong learning, especially for leadership skills.

The problem for the blue-collar worker is more obvious. Union rules have often discouraged personal growth. Narrow job classifications, for example, weren’t designed to reduce learning, but that has been one of the consequences. In a stable environment, we could live with those kinds of rules. In a rapidly changing globalized marketplace, we probably cannot.

The old white-collar career path did help people learn, but only in narrow functional grooves. One had to absorb more and more knowledge about accounting (or engineering or marketing), but little else. To progress beyond a certain level, one had to learn about management, but not much about leadership.

Successful twenty-first-century careers will be more dynamic. Already we are seeing less linear movement up a single hierarchy. Already we are seeing fewer people doing one job the same way for long periods of time. The greater uncertainty and volatility tend to be uncomfortable for people at first. But most of us seem to get used to it. And the benefits can certainly be significant.

People who learn to master more volatile career paths also usually become more comfortable with change generally and thus better able to play more useful roles in organizational transformations. They more easily develop whatever leadership potential they have. With more leadership, they are in a better position to help their employers advance the transformation process so as to significantly improve meaningful results while minimizing the painful effects of change.

That Necessary Leap into the Future

For a lot of reasons, many people are still embracing the twentieth-century career and growth model. Sometimes complacency is the problem. They have been successful, so why change? Sometimes they have no clear vision of the twenty-first century, and so they don’t know how they should change. But often fear is a key issue. They see jobs seeming to disappear all around them. They hear horror stories about people who have been downsized or reengineered out of work. They worry about health insurance and the cost of college for their children. So they don’t think about growth. They don’t think about personal renewal. They don’t think about developing whatever leadership potential they have. Instead they cling defensively to what they currently have. In effect, they embrace the past, not the future.

A strategy of embracing the past will probably become increasingly ineffective over the next few decades. Better for most of us to start learning now how to cope with change, to develop whatever leadership potential we have, and to help our organizations in the transformation process. Better for most of us, despite the risks, to leap into the future. And to do so sooner rather than later.

As an observer of life in organizations, I think I can say with some authority that people who are making an effort to embrace the future are a happier lot than those who are clinging to the past. That is not to say that learning how to become a part of the twenty-first-century enterprise is easy. But people who are attempting to grow, to become more comfortable with change, to develop leadership skills—these men and women are typically driven by a sense that they are doing what is right for themselves, their families, and their organizations. That sense of purpose spurs them on and inspires them during rough periods.

And those people at the top of enterprises today who encourage others to leap into the future, who help them overcome natural fears, and who thus expand the leadership capacity in their organizations—these people provide a profoundly important service for the entire human community.

We need more of those people. And we will get them.