Transforming Organizations: Why Firms Fail

By any objective measure, the amount of significant, often traumatic, change in organizations has grown tremendously over the past two decades. Although some people predict that most of the reengineering, restrategizing, mergers, downsizing, quality efforts, and cultural renewal projects will soon disappear, I think that is highly unlikely. Powerful macroeconomic forces are at work here, and these forces may grow even stronger over the next few decades. As a result, more and more organizations will be pushed to reduce costs, improve the quality of products and services, locate new opportunities for growth, and increase productivity.

To date, major change efforts have helped some organizations adapt significantly to shifting conditions, have improved the competitive standing of others, and have positioned a few for a far better future. But in too many situations the improvements have been disappointing and the carnage has been appalling, with wasted resources and burned-out, scared, or frustrated employees.

To some degree, the downside of change is inevitable. Whenever human communities are forced to adjust to shifting conditions, pain is ever present. But a significant amount of the waste and anguish we’ve witnessed in the past decade is avoidable. We’ve made a lot of errors, the most common of which are these.

Error #1: Allowing Too Much Complacency

By far the biggest mistake people make when trying to change organizations is to plunge ahead without establishing a high enough sense of urgency in fellow managers and employees. This error is fatal because transformations always fail to achieve their objectives when complacency levels are high.

When Adrien was named head of the specialty chemicals division of a large corporation, he saw lurking on the horizon many problems and opportunities, most of which were the product of the globalization of his industry. As a seasoned and self-confident executive, he worked day and night to launch a dozen new initiatives to build business and margins in an increasingly competitive marketplace. He realized that few others in his organization saw the dangers and possibilities as clearly as he did, but he felt this was not an insurmountable problem. They could be induced, pushed, or replaced.

Two years after his promotion, Adrien watched initiative after initiative sink in a sea of complacency. Regardless of his inducements and threats, the first phase of his new product strategy required so much time to implement that competitor countermoves offset any important benefit. He couldn’t secure sufficient corporate funding for his big reengineering project. A reorganization was talked to death by skilled filibusterers on his staff. In frustration, Adrien gave up on his own people and acquired a much smaller firm that was already successfully implementing many of his ideas. Then, in a subtle battle played out over another two years, he watched with amazement and horror as people in his division with little sense of urgency not only ignored all the powerful lessons in the acquisition’s recent history but actually stifled the new unit’s ability to continue to do what it had been doing so well.

Smart individuals like Adrien fail to create sufficient urgency at the beginning of a business transformation for many different but interrelated reasons. They overestimate how much they can force big changes on an organization. They underestimate how hard it is to drive people out of their comfort zones. They don’t recognize how their own actions can inadvertently reinforce the status quo. They lack patience: “Enough with the preliminaries, let’s get on with it.” They become paralyzed by the downside possibilities associated with reducing complacency: people becoming defensive, morale and short-term results slipping. Or, even worse, they confuse urgency with anxiety, and by driving up the latter they push people even deeper into their foxholes and create even more resistance to change.

If complacency were low in most organizations today, this problem would have limited importance. But just the opposite is true. Too much past success, a lack of visible crises, low performance standards, insufficient feedback from external constituencies, and more all add up to: “Yes, we have our problems, but they aren’t that terrible and I’m doing my job just fine,” or “Sure we have big problems, and they are all over there.” Without a sense of urgency, people won’t give that extra effort that is often essential. They won’t make needed sacrifices. Instead they cling to the status quo and resist initiatives from above. As a result, reengineering bogs down, new strategies fail to be implemented well, acquisitions aren’t assimilated properly, downsizings never get at those least necessary expenses, and quality programs become more surface bureaucratic talk than real business substance.

Error #2: Failing to Create a Sufficiently Powerful Guiding Coalition

Major change is often said to be impossible unless the head of the organization is an active supporter. What I am talking about here goes far beyond that. In successful transformations, the president, division general manager, or department head plus another five, fifteen, or fifty people with a commitment to improved performance pull together as a team. This group rarely includes all of the most senior people because some of them just won’t buy in, at least at first. But in the most successful cases, the coalition is always powerful—in terms of formal titles, information and expertise, reputations and relationships, and the capacity for leadership. Individuals alone, no matter how competent or charismatic, never have all the assets needed to overcome tradition and inertia except in very small organizations. Weak committees are usually even less effective.

Efforts that lack a sufficiently powerful guiding coalition can make apparent progress for a while. The organizational structure might be changed, or a reengineering effort might be launched. But sooner or later, countervailing forces undermine the initiatives. In the behind-the-scenes struggle between a single executive or a weak committee and tradition, short-term self-interest, and the like, the latter almost always win. They prevent structural change from producing needed behavior change. They kill reengineering in the form of passive resistance from employees and managers. They turn quality programs into sources of more bureaucracy instead of customer satisfaction.

As director of human resources for a large U.S.-based bank, Claire was well aware that her authority was limited and that she was not in a good position to head initiatives outside the personnel function. Nevertheless, with growing frustration at her firm’s inability to respond to new competitive pressures except through layoffs, she accepted an assignment to chair a “quality improvement” task force. The next two years would be the least satisfying in her entire career.

The task force did not include even one of the three key line managers in the firm. After having a hard time scheduling the first meeting—a few committee members complained of being exceptionally busy—she knew she was in trouble. And nothing improved much after that. The task force became a caricature of all bad committees: slow, political, aggravating. Most of the work was done by a small and dedicated subgroup. But other committee members and key line managers developed little interest in or understanding of this group’s efforts, and next to none of the recommendations was implemented. The task force limped along for eighteen months and then faded into oblivion.

Failure here is usually associated with underestimating the difficulties in producing change and thus the importance of a strong guiding coalition. Even when complacency is relatively low, firms with little history of transformation or teamwork often undervalue the need for such a team or assume that it can be led by a staff executive from human resources, quality, or strategic planning instead of a key line manager. No matter how capable or dedicated the staff head, guiding coalitions without strong line leadership never seem to achieve the power that is required to overcome what are often massive sources of inertia.

Error #3: Underestimating the Power of Vision

Urgency and a strong guiding team are necessary but insufficient conditions for major change. Of the remaining elements that are always found in successful transformations, none is more important than a sensible vision.

Vision plays a key role in producing useful change by helping to direct, align, and inspire actions on the part of large numbers of people. Without an appropriate vision, a transformation effort can easily dissolve into a list of confusing, incompatible, and time-consuming projects that go in the wrong direction or nowhere at all. Without a sound vision, the reengineering project in the accounting department, the new 360-degree performance appraisal from human resources, the plant’s quality program, and the cultural change effort in the sales force either won’t add up in a meaningful way or won’t stir up the kind of energy needed to properly implement any of these initiatives.

Sensing the difficulty in producing change, some people try to manipulate events quietly behind the scenes and purposefully avoid any public discussion of future direction. But without a vision to guide decision making, each and every choice employees face can dissolve into an interminable debate. The smallest of decisions can generate heated conflict that saps energy and destroys morale. Insignificant tactical choices can dominate discussions and waste hours of precious time.

In many failed transformations, you find plans and programs trying to play the role of vision. As the so-called quality czar for a communications company, Conrad spent much time and money producing four-inch-thick notebooks that described his change effort in mind-numbing detail. The books spelled out procedures, goals, methods, and deadlines. But nowhere was there a clear and compelling statement of where all this was leading. Not surprisingly, when he passed out hundreds of these notebooks, most of his employees reacted with either confusion or alienation. The big thick books neither rallied them together nor inspired change. In fact, they may have had just the opposite effect.

In unsuccessful transformation efforts, management sometimes does have a sense of direction, but it is too complicated or blurry to be useful. Recently I asked an executive in a midsize British manufacturing firm to describe his vision and received in return a barely comprehensible thirty-minute lecture. He talked about the acquisitions he was hoping to make, a new marketing strategy for one of the products, his definition of “customer first,” plans to bring in a new senior-level executive from the outside, reasons for shutting down the office in Dallas, and much more. Buried in all this were the basic elements of a sound direction for the future. But they were buried, deeply.

A useful rule of thumb: Whenever you cannot describe the vision driving a change initiative in five minutes or less and get a reaction that signifies both understanding and interest, you are in for trouble.

Error #4: Undercommunicating the Vision by a Factor of 10 (or 100 or Even 1,000)

Major change is usually impossible unless most employees are willing to help, often to the point of making short-term sacrifices. But people will not make sacrifices, even if they are unhappy with the status quo, unless they think the potential benefits of change are attractive and unless they really believe that a transformation is possible. Without credible communication, and a lot of it, employees’ hearts and minds are never captured.

Three patterns of ineffective communication are common, all driven by habits developed in more stable times. In the first, a group actually develops a pretty good transformation vision and then proceeds to sell it by holding only a few meetings or sending out only a few memos. Its members, thus having used only the smallest fraction of the yearly intracompany communication, react with astonishment when people don’t seem to understand the new approach. In the second pattern, the head of the organization spends a considerable amount of time making speeches to employee groups, but most of her managers are virtually silent. Here vision captures more of the total yearly communication than in the first case, but the volume is still woefully inadequate. In the third pattern, much more effort goes into newsletters and speeches, but some highly visible individuals still behave in ways that are antithetical to the vision, and the net result is that cynicism among the troops goes up while belief in the new message goes down.

One of the finest CEOs I know admits to failing here in the early 1980s. “At the time,” he tells me, “it seemed like we were spending a great deal of effort trying to communicate our ideas. But a few years later, we could see that the distance we went fell short by miles. Worse yet, we would occasionally make decisions that others saw as inconsistent with our communication. I’m sure that some employees thought we were a bunch of hypocritical jerks.”

Communication comes in both words and deeds. The latter is generally the most powerful form. Nothing undermines change more than behavior by important individuals that is inconsistent with the verbal communication. And yet this happens all the time, even in some well-regarded companies.

Error #5: Permitting Obstacles to Block the New Vision

The implementation of any kind of major change requires action from a large number of people. New initiatives fail far too often when employees, even though they embrace a new vision, feel disempowered by huge obstacles in their paths. Occasionally, the roadblocks are only in people’s heads and the challenge is to convince them that no external barriers exist. But in many cases, the blockers are very real.

Sometimes the obstacle is the organizational structure. Narrow job categories can undermine efforts to increase productivity or improve customer service. Compensation or performance-appraisal systems can force people to choose between the new vision and their self-interests. Perhaps worst of all are supervisors who refuse to adapt to new circumstances and who make demands that are inconsistent with the transformation.

One well-placed blocker can stop an entire change effort. Ralph did. His employees at a major financial services company called him “The Rock,” a nickname he chose to interpret in a favorable light. Ralph paid lip service to his firm’s major change efforts but failed to alter his behavior or to encourage his managers to change. He didn’t reward the ideas called for in the change vision. He allowed human resource systems to remain intact even when they were clearly inconsistent with the new ideals. With these actions, Ralph would have been disruptive in any management job. But he wasn’t in just any management job. He was the number three executive at his firm.

Ralph acted as he did because he didn’t believe his organization needed major change and because he was concerned that he couldn’t produce both change and the expected operating results. He got away with this behavior because the company had no history of confronting personnel problems among executives, because some people were afraid of him, and because his CEO was concerned about losing a talented contributor. The net result was disastrous. Lower-level managers concluded that senior management had misled them about their commitment to transformation, cynicism grew, and the whole effort slowed to a crawl.

Whenever smart and well-intentioned people avoid confronting obstacles, they disempower employees and undermine change.

Error #6: Failing to Create Short-Term Wins

Real transformation takes time. Complex efforts to change strategies or restructure businesses risk losing momentum if there are no short-term goals to meet and celebrate. Most people won’t go on the long march unless they see compelling evidence within six to eighteen months that the journey is producing expected results. Without short-term wins, too many employees give up or actively join the resistance.

Creating short-term wins is different from hoping for short-term wins. The latter is passive, the former active. In a successful transformation, managers actively look for ways to obtain clear performance improvements, establish goals in the yearly planning system, achieve these objectives, and reward the people involved with recognition, promotions, or money. In change initiatives that fail, systematic effort to guarantee unambiguous wins within six to eighteen months is much less common. Managers either just assume that good things will happen or become so caught up with a grand vision that they don’t worry much about the short term.

Nelson was by nature a “big ideas” person. With assistance from two colleagues, he developed a conception for how his inventory control (IC) group could use new technology to radically reduce inventory costs without risking increased stock outages. The three managers plugged away at implementing their vision for a year, then two. By their own standards, they accomplished a great deal: new IC models were developed, new hardware was purchased, new software was written. By the standards of skeptics, especially the divisional controller, who wanted to see a big dip in inventories or some other financial benefit to offset the costs, the managers had produced nothing. When questioned, they explained that big changes require time. The controller accepted that argument for two years and then pulled the plug on the project.

People often complain about being forced to produce short-term wins, but under the right circumstances that kind of pressure can be a useful element in a change process. When it becomes clear that quality programs or cultural change efforts will take a long time, urgency levels usually drop. Commitments to produce short-term wins can help keep complacency down and encourage the detailed analytical thinking that can usefully clarify or revise transformational visions.

In Nelson’s case, that pressure could have forced a few money-saving course corrections and speeded up partial implementation of the new inventory control methods. And with a couple of short-term wins, that very useful project would probably have survived and helped the company.

Error #7: Declaring Victory Too Soon

After a few years of hard work, people can be tempted to declare victory in a major change effort with the first major performance improvement. While celebrating a win is fine, any suggestion that the job is mostly done is generally a terrible mistake. Until changes sink down deeply into the culture, which for an entire company can take three to ten years, new approaches are fragile and subject to regression.

In the recent past, I have watched a dozen change efforts operate under the reengineering theme. In all but two cases, victory was declared and the expensive consultants were paid and thanked when the first major project was completed, despite little, if any, evidence that the original goals were accomplished or that the new approaches were being accepted by employees. Within a few years, the useful changes that had been introduced began slowly to disappear. In two of the ten cases, it’s hard to find any trace of the reengineering work today.

I recently asked the head of a reengineering-based consulting firm if these instances were unusual. She said: “Not at all, unfortunately. For us, it is enormously frustrating to work for a few years, accomplish something, and then have the effort cut off prematurely. Yet it happens far too often. The time frame in many corporations is too short to finish this kind of work and make it stick.”

Over the past few decades, I’ve seen the same sort of thing happen to quality projects, organization development efforts, and more. Typically, the problems start early in the process: the urgency level is not intense enough, the guiding coalition is not powerful enough, the vision is not clear enough. But the premature victory celebration stops all momentum. And then powerful forces associated with tradition take over.

Ironically, a combination of idealistic change initiators and self-serving change resisters often creates this problem. In their enthusiasm over a clear sign of progress, the initiators go overboard. They are then joined by resisters, who are quick to spot an opportunity to undermine the effort. After the celebration, the resisters point to the victory as a sign that the war is over and the troops should be sent home. Weary troops let themselves be convinced that they won. Once home, foot soldiers are reluctant to return to the front. Soon thereafter, change comes to a halt and irrelevant traditions creep back in.

Declaring victory too soon is like stumbling into a sinkhole on the road to meaningful change. And for a variety of reasons, even smart people don’t just stumble into that hole. Sometimes they jump in with both feet.

Error #8: Neglecting to Anchor Changes Firmly in the Corporate Culture

In the final analysis, change sticks only when it becomes “the way we do things around here,” when it seeps into the very bloodstream of the work unit or corporate body. Until new behaviors are rooted in social norms and shared values, they are always subject to degradation as soon as the pressures associated with a change effort are removed.

Two factors are particularly important in anchoring new approaches in an organization’s culture. The first is a conscious attempt to show people how specific behaviors and attitudes have helped improve performance. When people are left on their own to make the connections, as is often the case, they can easily create inaccurate links. Because change occurred during charismatic Coleen’s time as department head, many employees linked performance improvements with her flamboyant style instead of the new “customer first” strategy that had in fact made the difference. As a result, the lesson imbedded in the culture was “Value Extroverted Managers” instead of “Love Thy Customer.”

Anchoring change also requires that sufficient time be taken to ensure that the next generation of management really does personify the new approach. If promotion criteria are not reshaped, another common error, transformations rarely last. One bad succession decision at the top of an organization can undermine a decade of hard work.

Poor succession decisions at the top of companies are likely when boards of directors are not an integral part of the effort. In three instances I have recently seen, the champions for change were retiring CEOs. Although their successors were not resisters, they were not change leaders either. Because the boards simply did not understand the transformations in any detail, they could not see the problem with their choice of successors. The retiring executive in one case tried unsuccessfully to talk his board into a less seasoned candidate who better personified the company’s new ways of working. In the other instances, the executives did not resist the board choices because they felt their transformations could not be undone. But they were wrong. Within just a few years, signs of new and stronger organizations began to disappear at all three companies.

Smart people miss the mark here when they are insensitive to cultural issues. Economically oriented finance people and analytically oriented engineers can find the topic of social norms and values too soft for their tastes. So they ignore culture—at their peril.

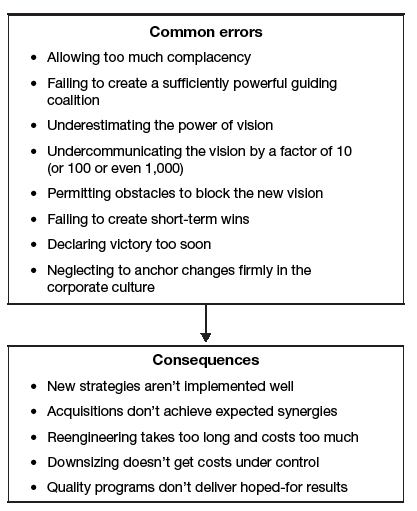

The Eight Mistakes

None of these change errors would be that costly in a slower-moving and less competitive world. Handling new initiatives quickly is not an essential component of success in relatively stable or cartel-like environments. The problem for us today is that stability is no longer the norm. And most experts agree that over the next few decades the business environment will become only more volatile.

Making any of the eight errors common to transformation efforts can have serious consequences (see figure 1–1). In slowing down the new initiatives, creating unnecessary resistance, frustrating employees endlessly, and sometimes completely stifling needed change, any of these errors could cause an organization to fail to offer the products or services people want at prices they can afford. Budgets are then squeezed, people are laid off, and those who remain are put under great stress. The impact on families and communities can be devastating. As I write this, the fear factor generated by this disturbing activity is even finding its way into presidential politics.

FIGURE 1-1

Eight errors common to organizational change efforts and their consequences

These errors are not inevitable. With awareness and skill, they can be avoided or at least greatly mitigated. The key lies in understanding why organizations resist needed change, what exactly is the multistage process that can overcome destructive inertia, and, most of all, how the leadership that is required to drive that process in a socially healthy way means more than good management.