15

Leading People Through Change

Pat Zigarmi and Judd Hoekstra

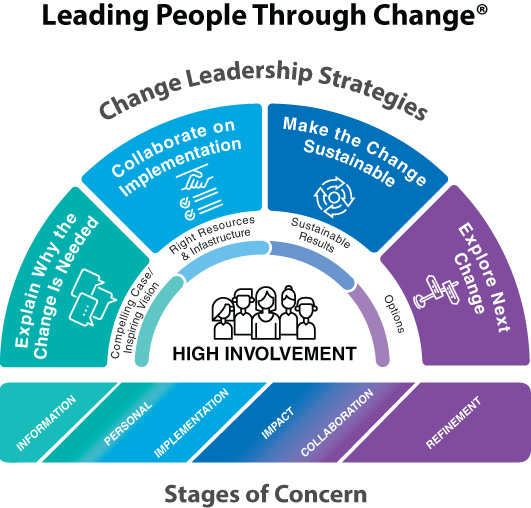

As we discussed in the last chapter, leaders often get overwhelmed when they implement change. In many ways, they feel trapped in a lose-lose situation. If they try to launch a disruptive change effort, they risk unleashing all kinds of pent-up negative feelings in people. On the other hand, if leaders don’t constantly drive change, their organizations will be displaced by organizations committed to innovation. It’s been said that if you don’t change, you’re dying. Add to that the fifteen Predictable Reasons Why Change Efforts Typically Fail, and it’s easy to see why leaders become immobilized around change. That’s why Pat Zigarmi and Judd Hoekstra developed a Leading People Through Change model—to make the seemingly complicated simple (see Figure 15.1.)1

Five Change Leadership Strategies

The Leading People Through Change model defines five change leadership strategies and their respective outcomes. These change leadership strategies are a response to the six stages of concern and serve as the antidote to the fifteen Predictable Reasons Why Change Efforts Typically Fail. They also describe a process for leading people through change that differs dramatically from how change is introduced in most organizations.

Change Strategy 1: Expand Involvement and Influence

Outcome: Buy-In

The first change leadership strategy, Expand Involvement and Influence, is at the heart of the Leading People Through Change model and must be used consistently throughout the change process to gain the cooperation and buy-in of others. This change strategy addresses four of the fifteen predictable reasons why change efforts fail:

People leading the change think that announcing the change is the same as implementing it.

People’s concerns with change are not surfaced or addressed.

Those being asked to change are not involved in planning the change.

The change leadership team does not include early adopters, resisters, or informal leaders.

The core belief of our approach to leading organizational change is that the best way to initiate, implement, and sustain change is to increase the level of influence and involvement from the people being asked to change, surfacing and resolving their concerns along the way. This was a key strategy in the preceding chapter.

Which of the following are you more likely to commit to: a decision made by others that is being imposed on you, or a decision you’ve had a chance to provide input into?

What may seem obvious to you isn’t obvious to many leaders trying to implement organizational changes. They believe change will be implemented much faster if they make quick decisions, and it is quicker to make decisions with fewer people providing input into the decision-making process. While it is true that decisions can be made faster when fewer people are involved, faster decisions may not translate into faster and better implementation. These change leaders believe that they can announce the change and it’s done! The “top-down, minimal involvement” leadership approach ignores the critical difference between compliance and commitment. People may comply with the new directive for a short time until the pressure is off, and then they typically return to old behavior because their concerns are not surfaced or addressed and they believe the change is being done to them, not with them.

Keep Figure 15.2 in mind as you think about how much you want to involve people in the change process. Resistance increases the more people sense that they cannot influence what is happening to them.

If people aren’t treated as if they are smart and would reach the same conclusion about the need to change as the change leadership team, they perceive a loss of control. Their world is about to change, but they have not been asked to talk about “what is” or “what could be.” Without involvement, there isn’t a vehicle for them to express and resolve their information concerns. Similarly, if personal concerns are not surfaced and acknowledged, people lose a sense of autonomy. They collude with others and become anxious, and their resistance increases. Then, when T-shirts with a slogan are given out and everyone is sent to “one size fits all” training, people begin to believe that the leadership really is out of touch with what is really happening in the organization. This puts their sense of control in jeopardy, which again increases resistance. The bottom line is that people have to influence the change they are expected to make, or, as Robert Lee said:

“People who are left out of shaping change have a way of reminding us that they are really important.”

There are lots of ways to involve people in the change process. They can be scouts for solutions that other organizations who are facing the same challenges have implemented. They can be asked to pilot the change. They can be brought onto the change leadership team optimally as members, minimally as advisors. Although it may feel uncomfortable at first, it is helpful to include at least one or two people who would be considered “resistant” and who can articulate the concerns of those who share that perspective on the change leadership team. When resisters have a forum to surface and address their concerns, they often become the most effective problem solvers and spokespeople for the change.

Ultimately, you want to engage the early adopters of the change as peer advocates. Peer advocates can often influence the people who are neutral to the change before they become resistant by helping build the business case for the change and by sharing their personal success with the change. You want to enlist them in training others and modeling the behaviors expected of others who are being asked to change.

The goal of a high involvement change strategy is to build a broad-based coalition of leaders at all levels who support the change and can advocate for the change with one voice to multiple stakeholders. If a diverse group of leaders from across the organization is aligned on the need for the change and how it will positively impact the organization, there is less resistance, less passivity, and less blaming. When people see a lack of alignment at the top, they know they don’t have to align. In addition, they know that because there is low alignment, the change will stall or derail and that they can outlast it. Remember: Sustainable organizational change happens through conversation and collaboration, not by unilateral action by a few.

High involvement also gets concerns and challenges on the table sooner. As a result, there is increased alignment and clarity about what and how things have to change, a better change implementation plan, and a higher probability of success. A favorite guideline we share with change leaders is this:

Those who plan the battle rarely battle the plan!

Flexibility: Using Several Different Change Leadership Strategies to Successfully Lead Change

The other four organizational change leadership strategies on the perimeter of the model proactively address the other Predictable Reasons Why Change Efforts Typically Fail.

When these change leadership strategies are thoughtfully used during a change process, a compelling case for the change and inspiring vision are created. The right resources and infrastructure are put in place to ensure successful implementation. Sustainable results are achieved. And options for ongoing innovation and change are explored.

To help make these change leadership strategies come alive, we offer the following case study involving a problem that has plagued millions of people in America. If you live outside the United States, you can probably come up with a similar “systems” change.

Case Study: Non-Support-Paying Parents

As many as 20 million children in America may have noncustodial parents who avoid child support obligations. According to the Federal Office of Child Support, the total unpaid child support in the United States is close to $100 billion, and 68 percent of child support cases are in arrears. An overwhelming majority of children—particularly minorities—residing in single-parent homes, where child support is not paid, live in poverty.

In the United States, child support enforcement is a loose confederation of state and local agencies all operating with different guidelines, all accountable to the Federal Office of Child Support Enforcement. Getting agencies to work together is the greatest challenge. While legislation exists to enforce child support payments, there is too much bureaucracy and not enough manpower to pursue non-support-paying parents across state lines and take them into custody. As a result, many of these parents beat the system.

Up until recently, information on these parents was stored in paper files in clerks’ offices in the county where the parent resided. County clerks were responsible for using this information to try to enforce the collection of child support payments. Often, as a county clerk got close to tracking down a parent not paying court-ordered child support payments, the parent would move to a different county or even a different state.

Without a system for sharing information stored in paper files across county lines or even state lines, it became nearly impossible to catch the non-support-paying parents. As a result, custodial parents and kids who were due to receive child support ended up losing the support they needed.

As frustration grew over this situation, the federal government decided to take on the challenge. Federal legislation was passed that mandated that each state implement an electronic tracking system that facilitated the sharing of current information across county and state lines to better enable the tracking of these parents. This may sound like a relatively simple change to make, considering computer use today. However, when the legislation was passed, many county clerks were in their fifties and sixties, lived in rural areas, had never used a computer, and had been trying to track non-support-paying parents with a notepad, pencil, and telephone for decades.

Do you think the county clerks being asked to change had concerns about the proposed change? Of course they did. Many of these county clerks had information concerns, such as how having an electronic tracking system would improve enforcement in their county. In counties that were already doing a good job of collecting child support, clerks wondered if they could continue using their paper files as long as they were successful. Counties that had been using a computer system for years to track cases wondered if they needed to use the new mandated system, or if they could keep using their current system. People wondered how long it would take to move the information from their paper files to the computer.

Many of the county clerks had personal concerns as well. People said things like, “How can I learn to use this new system? If I can’t learn to use the new tracking system and software, will I still have a job? Besides being told to use the new electronic tracking system, how else is my job changing? This sounds like a lot of extra work. I’m not ready for this.” These questions are typical at this stage of the change process and reflective of fears that the change would probably make their work harder.

In addition, the clerks had implementation concerns. They wanted to know when they would be trained on the new electronic tracking system. They wanted to know who to contact if they needed help after training. Many wondered if any counties were “going live” before they were and if they could talk with people in those counties. They also wondered when the whole state would be up and running on the new system. Finally, they wondered what would happen if the electronic tracking system went down or was unavailable.

Once the change was in motion, some of the clerks brought forward impact concerns. For example, they wanted to know if they were catching any non-support-paying parents they wouldn’t have caught without the new system. They wanted to know how much more money they were collecting compared to when they were doing things the old way. Many were curious to know if custodial parents who began receiving payments saw positive changes in how they worked with the clerks and in the amount of money they were collecting. They wanted to know how much more money they were collecting compared to when they were doing things the old way. Many were curious to know if their customers (custodial parents) saw a positive change in how they were working with them and the results they were achieving.

In time, the clerks’ collaboration concerns began to surface. Here are some of their comments: “I’ve seen the success of this new system firsthand. Is there anybody who is not yet convinced that this is a good idea? It will only work if we do it across the state and across the country.”

“I’m so glad I got to be part of the pilot. I can’t wait to go back to my county and share the results we’ve achieved. There are a lot of people who are currently pretty skeptical about this new system.”

“The system is working pretty well within the counties around us that have ‘gone live.’ But we need to broaden the implementation and connect every county in the country to a common database.”

Once the new system was up and running, the clerks brought forward their refinement concerns. While they acknowledged that the new system was an improvement over how things used to be, they suggested areas that might be improved. For example, a question came up about how they could connect their system to other systems (other county and state child support systems, the Department of Motor Vehicles, the new-hire database, the IRS) so that they could better track people and enforce the collection of child support. So, how did those responsible for this massive systems change decrease information, personal, and implementation concerns and create buy-in for the proposed change?

Change Strategy 2: Explain Why the Change Is Needed

Outcome: A Compelling Business Case and Inspiring Vision for the Change

The second change leadership strategy is Explain Why the Change Is Needed. This strategy addresses the following two reasons why change efforts fail:

5. There is no compelling reason to change. The business case is not communicated.

6. A compelling vision that excites people about the future has not been developed and communicated.

This second change leadership strategy addresses information concerns and, to some extent, personal concerns.

When leaders explain why the change is needed, the outcome is a compelling case that helps people understand the change being proposed, the rationale for the change, and why the status quo is no longer a viable option.

When you lead a change initiative, expect that many people in the organization will not understand the need for a change; they will feel good about the work they are currently doing. As a result, they will have information concerns and likely will ask questions such as, “What is the change? Why is it needed? What’s wrong with the way things are now? How much and how fast does the organization need to change?”

Most likely, those initiating the change were frustrated by something that was wrong with the status quo or were anxious about an opportunity that would be lost by continuing with business as usual. This spirit of discontent with the status quo needs to be shared and felt by those being asked to change.

You need to create enough disequilibrium to create change, but not so much that others fight, flee, or freeze.

Suppose a leader mistakenly attempts to create and communicate a change-specific vision to the organization before demonstrating that the status quo is no longer a viable option. The inertia of the status quo will likely prove too strong, and the very people whose cooperation the leader needs will be much less likely to embrace the picture of the future the leader intends to create. As John Maynard Keynes2 said:

“The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.”

In the child support example described earlier, it was critical to have custodial parents and county clerks share their stories about the frustration and hopelessness they felt in trying to track down and enforce the collection of child support from non-support-paying parents with only pen-and-paper support from government agents. Without county clerks feeling this frustration, it was very unlikely that they would be willing to learn a new electronic tracking system and adopt new ways of working just because it was mandated by federal legislators.

As you build the case for change, one of the best ways to get buy-in from employees is to share information broadly and then ask people at all levels in the organization to tell you why they believe the organization needs to change.

To do that, bring people face to face with the reality of what is prompting the need for change. Think of it as turning up the thermostat to create discomfort and a sense of urgency that the change is needed. Ask people for their reasons why the organization needs to change even if you already think you know the answers. When they respond, don’t respond with certainty. It will lead to overselling what you know and discounting what you don’t know.

Go toward resisters, and learn why they are resisting. By doing so, your case for change will be more compelling in people’s eyes because they came up with it. As a result of their ownership in making the case for change, people are much more likely to leave the status quo behind.

Returning to the example we cited in Chapter 3, “Empowerment Is the Key,” The Ken Blanchard Companies® needed to make several changes as a result of the economic downturn following the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. The leaders shared information broadly with the organization regarding projected revenue, current expenses, and break-even figures. This brought people face to face with the reality of the situation and ensured that everyone in the organization understood that “business as usual” was no longer a viable option. Then the leaders asked associates what would happen if the status quo were maintained. The associates clearly stated that the company’s survival was at stake. As a result of their involvement in building the case for change, associates bought into a number of cost-cutting initiatives, even when the initiatives weren’t in their own best interest.

Once a gap between what is and what could be is identified, an inspiring vision of the future needs to be shared. An inspiring vision is what creates a commitment to change.

The process used to create a vision, whether it is for an entire organization or for a specific change initiative, is the same. This process is described in detail in Chapter 2, “The Power of Vision.” As Ken Blanchard and Jesse Stoner point out in Full Steam Ahead! Unleash the Power of Vision in Your Company and Your Life, the process you use to develop a vision is as important as the vision itself. In other words, if people are involved in the process and feel the vision is theirs—as opposed to some words on a poster from an executive retreat—they are more likely to see themselves as part of the future when the change is implemented. When they are involved in creating the picture of the future, they begin to believe they will adapt, and they will be much more likely to show the tenacity needed during the challenging times that inevitably accompany change.

Getting people involved in the visioning process is also a key way to help them resolve the personal concerns they experience during a change. The more you can get people involved in the visioning process, the more likely it is they will want to be part of the future organization. They need to be able to see themselves in the picture of the future for it to inspire them. This is why it is so important for leaders to understand the fears, aspirations, and loyalties of the people being asked to change.

In our earlier child support example, the change leadership team was responsible for drafting the initial vision. Because there was no existing vision for the state’s Child Support Program to compare it to, they needed to create a brand new vision for the entire program, not just for the implementation of the new electronic tracking system. Next, they took the draft vision to the county clerks across the state and asked them for input. The result was the creation of a shared vision that was compelling for the majority of those being asked to change. It read:

Our state’s Child Support Program helps children thrive by providing financial stability to their families and offering the highest-quality service as a nationally recognized model of excellence for child support enforcement.

While a small group of leaders could have come up with these words, giving the county clerks who were being asked to change an opportunity to provide input ensured that the vision was understood and embraced.

Change Strategy 3: Collaborate on Implementation

Outcome: The Right Resources and Infrastructure

The third change leadership strategy, Collaborate on Implementation, is designed to create the right conditions for the successful implementation of the change and to surface and address personal and implementation concerns.

When leaders engage others in planning and piloting the change, they encourage collaborative effort in identifying the right resources and building the infrastructure needed to support the change. This change leadership strategy addresses the following reasons why change efforts fail:

7. The change is not piloted, so the organization does not learn what is needed to support the change.

8. Organizational systems and other initiatives are not aligned with the change.

9. Leaders lose focus or fail to prioritize, causing “death by 1,000 initiatives.”

There are lots of ways organizations can involve others in crafting successful change implementation plans. They include:

Involve others in planning and pilots. We’ve all seen or been part of changes that have not gone well. In most of these cases, the implementation plan was not developed by people anywhere near the front line. As a result, the plan did not account for some real-world realities and was shrugged off as flawed, unrealistic, and lacking the details required for action—or, worse yet, flat-out wrong.

As with the earlier change leadership strategies we described, when you involve people and give them a chance to influence, you get not only their buy-in, but a better outcome. Your planning process needs to account for the fact that you won’t have it all figured out ahead of time. Run some experiments or pilots with early adopters to work out the kinks and learn more about the best way to implement the change with the larger organization. Ensure that your change implementation plan is dynamic.

By getting others involved in the planning process, you can surface and resolve many lingering personal and implementation concerns.

Here’s an old adage we love:

“Listen to the whispers to avoid the screams.”

Test drives, pilots, and experiments can also teach you what else needs to change in terms of policies, procedures, systems, and structures so that the probability of successful implementation across the larger organization improves. The positive outcomes of engaging others at this stage of the change process are collaborative effort, a high degree of alignment on the best way to implement the change, a realistic assessment of the resources needed, and the right infrastructure.

Many change plans underestimate the momentum generated by short-term wins that can be realized when the change is piloted. Short-term wins are improvements that can be implemented within a short time frame—typically three months—with minimal resources, at minimal cost, and at minimal risk.

Pilots that result in short-term wins have several benefits. First, they address implementation concerns around the mechanics of the change, priorities, and obstacles to the efficient implementation of the change. Second, they proactively address impact concerns (such as “Is the change working?”). Third, pilots get more people involved with influencing the change, generating more buy-in. Fourth, they provide good news early in the change effort, when good news is hard to come by. Fifth, they reinforce behavior changes made by early adopters. Sixth, they help sway those who are “on the fence” toward action. Remember, motion creates emotion.

In the child support case study pilot described earlier, it was critical to select counties that had the greatest probability of seeing significant short-term results from implementing the new electronic tracking system. This would help surface and address implementation concerns and build momentum for post-pilot implementations with other counties where the impact was more in question.

Avoid death by 1,000 initiatives. With limited resources, it is critical to make choices about what change initiatives will allow your organization to achieve its vision most effectively and efficiently. Individual change initiatives need to be scheduled and implemented in light of other activities and initiatives competing for people’s time, energy, and mindshare.

During times of change, it is critical to provide people with direction on priorities. Like a sponge, after a certain amount of change, people cannot absorb any more, no matter how resilient and adaptive they are. Another way to involve others in the implementation of change is to ask those impacted by the change about what work processes, systems, and policies need to change to ensure successful implementation.

Decide what not to do. While it is important to provide direction on what to do, it is just as important to provide direction on what not to do. Ask the following questions: What project or initiative will have the greatest impact on your vision? What provides the greatest value for resources expended (money, people, time)? Can the people responsible for working on the project handle it with all the other things they have been assigned to do? Are there enough qualified people who can dedicate time to work on the project? Are there any synergies between this project and other critical projects?

Once you have prioritized and sequenced a list of possible change projects, recognize that, because we live in a dynamic environment, priorities can shift and resources can become more abundant or scarce. This may shift the type and number of projects an organization undertakes at any point in time as well. Prioritizing change initiatives and steps within a single change initiative is a key tactic for lowering implementation concerns.

Decide how and when to measure and assess progress. The adage is true: What gets measured gets done. Because it is difficult to predict human behavior with absolute certainty—especially in the face of major change—assess the progress being made on a number of fronts in an effort to identify potential risks to the change’s success. These areas include sponsor commitment, employee commitment and behavior change, the achievement of project milestones, and progress toward the accomplishment of business results.

The measurement plan crafted at this step needs to describe what will be measured, how it will be measured, and how frequently it will be measured. To increase the probability of successful change, consider using Blanchard’s Change Readiness Survey3 to determine what’s working well and what requires additional work. And constantly ask the early adopters of the change how they think it’s going.

Communicate, communicate, communicate. Much has been written about the importance of communication during times of change. Why is it so important? A significant amount of resistance encountered during organizational change is caused by a lack of information, especially details about the what, why, and how. In the absence of honest, passionate, and empathetic communication, people create their own information about the change, and rumors begin to serve as facts.

For example, we worked with an organization going through a tremendous amount of change. As we started our work, we quickly realized that little or no rationale was being provided for key decisions that affected a large number of people. Without supporting rationale, the facts appeared harsh to team members:

The development project I was working on was stopped.

My budget was cut.

Based on these facts alone, many people assumed that the company’s future was bleak. As a result, tremendous effort was required to overcome the rumor mill that led to drops in productivity and morale and caused some people to begin looking for other jobs.

Let’s consider these same facts, only this time with supporting rationale. Can you see how providing this rationale could have prevented the rumors and resistance that occurred?

The project I was working on was stopped because we found that customer safety was at risk. Customer safety is our highest-priority value, so we made a decision in line with our values.

My budget was cut because the organization is reallocating these funds toward another drug development project based on a recent licensing agreement we signed.

Some of the strongest resistance to change occurs when reality differs from expectations. Therefore, understanding the current expectations of those affected by the change is critical if leaders are to manage and shape or transform those expectations effectively.

Recognize that covert resistance kills change. Effective leaders not only tolerate the open expression of concerns, they actually reward their people for sharing their concerns in an open, honest, and constructive manner. It is critical that leaders provide opportunities for two-way communication because concerns cannot be surfaced and resolved without give-and-take dialogue.

It is also important to recognize that communicating your message once is not enough for most people to act on it. People in organizations are so bombarded with information that one of the best ways to sort out what requires action versus what does not is to listen for the messages that are communicated repeatedly over time. These can be distinguished from the flavor-of-the-month messages that come and go. Communicate your key messages at least seven times in seven different ways. Better yet, communicate them at least ten times in ten different ways.

Change Strategy 4: Make the Change Sustainable

Outcome: Sustainable Results

The fourth change leadership strategy, Make the Change Sustainable, addresses both implementation and impact concerns. When leaders make the change sustainable, they set the stage for sustainable results. This encourages people to embrace the change, develop new skills, and make a deeper commitment to the organization. This change leadership strategy addresses the following reasons why change efforts fail.

10. People are not enabled or encouraged to build new skills.

11. Those leading the change are not credible; they undercommunicate, give mixed messages, and do not model the behaviors the change requires.

12. Progress is not measured, or no one recognizes the changes that people have worked hard to make.

13. People are not held accountable for implementing the change.

Our experience has shown that most organizations jump into this change leadership strategy—Make the Change Sustainable—much too soon. In many cases, executives announce the change and try to get people into training as soon as possible. Unfortunately, people’s information and personal concerns have not yet been addressed, so the results of the training are less than optimal. Also, training often is delivered before all the kinks are worked out, contingencies are planned for, help desks are created, or systems are aligned. Finally, early training usually fails because it’s “one size fits all.” After the learnings from pilots and experiments are culled and the right infrastructure is in place, training for the change should be done in as individualized a way as possible. Ideally, a training strategy for each individual should be delivered at just the right time.

Notice how three other change leadership strategies come before the Make Change Sustainable strategy. There is a reason for this—namely, because most organizations don’t do a good job on the early work that needs to be done to set up a successful change. The rallying cry we often hear in our work with organizations going through change is, “We’re raising the bar!” This rallying cry is not bad in and of itself. However, nothing kills motivation faster than telling people to raise their performance but failing to provide them with the new skills, tools, and resources required to leap over the height of the recently raised bar. As a result, people’s reaction to leadership’s statement that “We’re raising the bar!” is often along the lines of “Do you mean that I’m not doing a good job now?”

After the roles, responsibilities, and competencies required for lasting change are determined, skill gaps need to be closed. As SLII® would suggest, leaders need to use a directing style 1 (with high direction and low support) or, more likely, a coaching style 2 (with high direction and high support) to build people’s competence and commitment. Leaders need to use mistakes as opportunities for further learning, and they need to praise progress.

In the child support case study we described earlier, a group of county clerks involved in the pilots were chosen to train other county clerks on the new electronic tracking system and new work processes. This brought county clerk trainees face to face with others in similar positions who had gone down the path before them. Because the trainers were speaking from a position of experience, they were credible and could set realistic expectations for what other county clerks could expect when their county “went live.”

In addition, the county clerks facilitating the training used the sessions as opportunities to gather additional input and ensure that the implementation plan was as strong as it could be.

When leaders pay attention to the change effort at this phase—rather than announcing the next change!—they create conditions for accountability and early results. Some tactics for Making Change Sustainable are:

Walking the talk. Although it is critical for the change leadership team to communicate with one voice, it is even more important that the change leaders walk their talk and model the behaviors they expect of others at this phase of the change cycle.

It is estimated that a leader’s actions are at least three times as important as what he or she says. Leaders need to display as much or more commitment to the change as the people they lead. People will assess what the leader does and doesn’t do to assess the commitment to the change. The minute that associates or colleagues sense that their leader is not committed or is acting inconsistently with the desired behaviors of the change, they will no longer commit themselves to the effort.

Measure, praise progress, and redirect when necessary. As stated earlier, what gets measured gets done. Keep in mind that people’s thoughts and actions are leading indicators of business and financial performance. Leading indicators allow you to drive by “looking through the windshield” rather than by relying solely on lagging indicators such as financial performance, which is akin to driving while looking in the rearview mirror.

Once measurement occurs, praise the progress that is being made. Don’t wait for perfect performance. If you do, you’ll be waiting a long time. This concept has been key to our teachings for decades:

The key to developing people and creating great organizations is to catch people doing things right and to accentuate the positive.

Because you’ve planned for short-term wins, you should be able to find and share success stories as a means of influencing people who remain on the fence. Follow through on your promise to recognize and reward the behavior you expect, and follow through on your promise to impose consequences for anyone attempting to derail the change program. This is the stage where you either redirect people’s efforts or let go of the people who continue to resist.

In our child support case study, the state government called monthly meetings for county clerks across the state with similar “go live” dates. During these meetings, each county was asked to share a success story as well as any challenges it was having. The idea of holding each county accountable for sharing a success story in front of its peers created some healthy competition to make the new tracking system work. It allowed early-adopting counties to sway those that were on the fence. Discussing the challenges also provided opportunities for learning that could be fed back into the design of the tracking system, the planning process, and the training of the next group of county clerks.

In another example, a change leadership team we worked with instituted the use of a “performance dashboard” to continually measure progress against a set of key performance indicators. The change leadership team met twice a month to discuss the plan’s progress, as seen by green, yellow, and red indicators on the performance dashboard. If a key performance indicator was green, this was praised and celebrated. If a key performance indicator was yellow or red, the team would discuss how best to redirect efforts to get that indicator back on track. This process held people accountable for performance and ensured that people got the direction and support they needed.

Kill bureaucracy. Bureaucracy kills change. At this phase of the change process it’s important again to involve others in identifying work processes, policies, and procedures that get in the way of the successful implementation of the change.

Change Strategy 5: Explore Possibilities

Outcome: Options

The fifth change leadership strategy, Explore Possibilities, addresses collaboration and refinement concerns.

This strategy addresses the final two reasons why change efforts typically fail.

14. People leading the change fail to respect the power of the culture to kill the change.

15. Possibilities and options are not explored before a specific change is chosen.

While a high performing change leadership team can generate enthusiasm and short-term success during times of change, it is critical that the change be embedded in the organization’s culture—its attitudes, beliefs, and behavior patterns—if it is to be sustainable.

If a change is introduced that is not aligned with the current culture, you must alter the existing culture to support the new initiative or accept that the change may not be sustainable. The best way to alter the culture is to go back to the organization’s vision and examine its values. Identify which values support the new culture and which don’t. Then define the behaviors that are consistent with the values, and create acknowledgment and accountability for behaving consistently with the values. It is energizing for an organization to do this in the context of implementing change.

In many cases, a change is implemented within some business units before other business units are engaged. The change process defined by the Leading People Through Change model needs to be repeated for each new business unit as it launches the change.

Citing our child support case study again, it was critical to ensure that all obstacles to using the new tracking system were removed. While there were some common obstacles to overcome for most counties, many obstacles differed by county. As a result, embedding the change on a local level required attention at the local level. Because ongoing support was provided, obstacles were removed, and the counties themselves sold each other on the benefits of implementing the new tracking system. Doing so allowed the initiative to be extended across an entire state and eventually the entire country.

Ideally, those who are closest to the problems and opportunities in an organization are the ones who come up with the options to be considered by the change leadership team. To ensure face validity and inclusion of the best options, the options identified should be reviewed by a representative sample of those being asked to change.

In our child support case study, custodial parents and county clerks across the country expressed frustration with the fact that non-support-paying parents were getting harder to track and more elusive than ever. As a result, the federal government took this input, explored the root causes of the problem, and identified several possible responses. Several change projects were chosen as part of an integrated strategy to enforce the collection of child support payments. These projects included but were not limited to withholding income from the noncustodial parent’s employer and intercepting income tax refunds, unemployment compensation benefits, and lottery winnings. The projects also included reporting to the credit bureau, suspending driver’s and professional licenses, locating bank assets, cross-matching new-hire reporting, suspending hunting and fishing licenses, denying passports, assigning liens, matching federal loan data, and automating child support operations, including interfaces with numerous other state agency systems.

Some of these options were potentially more feasible and would have more impact than others. By simply having options, people felt they had choices and could influence what changed.

Since the electronic enforcement tracking system was implemented, annual child support collections have increased from $177 million to more than $460 million. Increased collections mean that more children are receiving the child support they deserve, and fewer families have to resort to public assistance to survive.4

The Importance of Reinforcing the Change

It is our hope that instructing leaders how to implement each change strategy and overcome the 15 reasons why change typically fails has taken much of the mystique out of the change process. Responding to others’ concerns and paying attention to how you increase involvement and influence at each step in the change process is the best way we know to build future change receptivity, capability, and leadership.

To summarize, here’s a good rule of thumb:

Organizations should spend ten times more energy reinforcing the change they just made than looking for the next great change to try.

*****

It’s worth repeating that if the change you’re introducing is not aligned with the current culture, you must re-create the existing culture to support the new change initiative. Given the importance of culture, in the next chapter we will discuss in detail how to build or transform an organizational culture.