There are a number of excellent web browsers available for Mac OS X, including Microsoft Internet Explorer, Chimera, Mozilla, Omniweb, and Opera. However, attractive, graphically based web browsers can be slow — especially with flashy, graphics-laden web pages on a slow network.

The Lynx web browser (originally from the University of Kansas, and available on many Unix systems) is different because it’s a text-based web browser that works within the Terminal application. Being text-only causes it to have some tradeoffs you should know about. Lynx indicates where graphics occur in a page layout; you won’t see the graphics, but the bits of text that Lynx uses in their place can clutter the screen. Still, because it doesn’t have to download or display those graphics, Lynx is fast, which is especially helpful over a dialup modem or busy network connection. Sites with complex multicolumn layouts can be hard to follow with Lynx; a good rule is to page through the screens, looking for the link you want and ignore the rest. Forms and drop-down lists are a challenge at first, but Lynx always gives you helpful hints for forms and lists, as well as other web page elements, in the third line from the bottom of the screen. With those warts (and others), though, once you get a feel for Lynx you may find yourself choosing to use it — even on a graphical system.

The Lynx command line syntax is:

lynx "location"For example, to visit the O’Reilly home page, enter

lynx

"http://www.oreilly.com" or

simply lynx

"www.oreilly.com".

(It’s safest to put

quotes around the

location, because many URLs have special characters that the shell

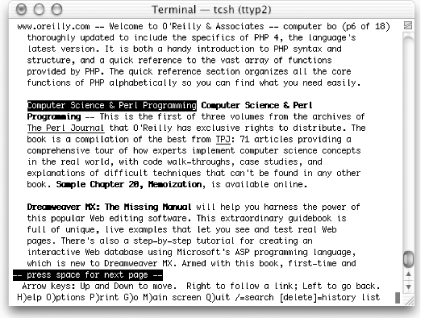

might interpret otherwise.) Figure 8-1 shows part

of the home page.

To move around the Web, Lynx uses your keyboard’s

arrow keys, spacebar, and a set of single-letter commands. The third

line from the bottom of a Lynx screen gives you a hint of what you

might want to do at the moment. In Figure 8-1, for

instance, “press space for next

page” means you can see the next screenful of this

web page by pressing the spacebar (at the bottom edge of your

keyboard). Lynx doesn’t use a scrollbar; instead,

use the spacebar to go forward in a page, and use the

b command to move back to the previous screenful

of the same web page. The bottom two lines of the screen remind you

of common commands, and the help system (which you get by typing

h) lists the rest.

The links (which you would click on if you were using a graphical web browser) are highlighted. One of those links is the currently selected link , which you can think of as the link where your cursor sits. Depending on how you’ve configured Terminal, links are either boldfaced or presented in a different color, and the selected link (in Figure 8-1, that’s the first: “Computer Science & Perl Programming”) is in reverse video.

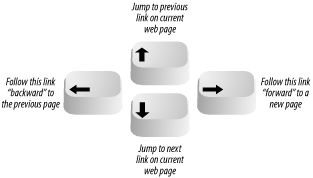

When you first view a screen, the link nearest the top is selected. Figure 8-2 shows what you can do at a selected link. To select a later link (farther down the page), press the down-arrow key. The up-arrow key selects the previous link (farther up the page). Once you’ve selected a link you want to visit, press the right-arrow key to follow that link; the new page appears. Go back to the previous page by pressing the left-arrow key (from any selected link; it doesn’t matter which one).

Although Lynx can’t display graphics in the Terminal (no program can!), it will let you download links that point to graphical files. Then you can use Aqua programs — such as Preview — to view or print those files.

There’s much more to Lynx; type H

for an overview. Lynx command-line options let you configure almost

everything. For a list of options,

type

man

lynx (see Section 10.1) or use:

% lynx -help | less