From Consensus to a Crisis of Confidence

The whole business community is going to have to get involved in political activities if our American way of life and our enterprise system, the free economy of this country, [are] going to survive.

—Joseph Coors, executive vice president, Adolph Coors Company, 1975

BUSINESSPEOPLE SHOULD HAVE BEEN HAPPY. The American economy soared during the 1960s, and in 1969 a Republican named Richard Nixon assumed the presidency, promising peace, prosperity, and a retreat from his predecessors’ “big government” policies. Yet despite that apparently sunny forecast, a collective sense of woe descended across the American business community as the 1970s dawned. Subdued in nervous whispers at first, the ominous refrain grew louder, echoing through boardrooms and conference centers, across golf courses and country clubs. By the middle of the decade, the once-low grumbling reached a fevered pitch, and despondent business leaders let loose a cacophonous scream:

“The American economic system is under broad attack,” cried a jurist.1

“The American capitalist system is confronting its darkest hour,” bemoaned an executive.2

“The existence of those free institutions which together make up the very fabric of the free society is in jeopardy,” proclaimed a think-tank director.3

“Yet those institutions are under attack, and the captains of industry stand helplessly by,” complained a senator.4

To myriad business owners, executives, and conservative politicians and intellectuals, the stakes could not have been higher. “The issue is survival!” they cried. Survival of capitalism. Survival of free enterprise. Survival of America.

But who was spearheading this dreaded attack? For conservative businesspeople, the culprit was neither the Soviet Union nor its secret agents hiding under every bed. Rather, this perilous attack on liberty and prosperity took root among the most American of institutions. The assault flowed, as one of the most publicized Cassandras put it, “from the college campus, the pulpit, the media, the intellectual and literary journals, the arts and sciences, and from politicians.”5 This sickness grew from a debilitating antibusiness bias that coursed through the veins of the American body politic, infecting national policy. Heavy-handed, hyper-regulatory government, abetted by a public deeply hostile to business, increasingly saddled American companies with resource-sapping regulations, devastating taxes, and crippling labor policies. For the self-styled defenders of American business, the stakes far exceeded narrow concerns like profits and productivity. This totalizing attack stood poised to undo the very fabric of the “free enterprise system” itself.6

To appreciate the depth of this fear and loathing, consider the firsthand accounts by a team of social scientists retained by the Conference Board, a nonadvocacy business association. Founded in 1916, the Conference Board had long endeavored, in the words of its founder, Magnus Alexander (an executive at General Electric), to serve as “a clearinghouse of [business and economic] information” that would “promote a clearer understanding between the employer … and the public.”7 Reaffirming that mission in 1974 and 1975, Conference Board president Alexander Trowbridge (former commerce secretary under Lyndon Johnson and future president of the National Association of Manufacturers) arranged a series of three-day meetings for business leaders from across industrial sectors to gather informally and discuss the topic of corporate social responsibility. To document the pervasiveness of business’s anxiety, Trowbridge invited two scholars: Leonard Silk, an academic economist and business columnist for the New York Times, and David Vogel, a young political scientist fresh out of graduate school at Princeton.

Like anthropologists in the bush, Silk and Vogel observed the Conference Board proceedings and conducted anonymous interviews with some 360 business leaders at eight weekend conferences over the course of a year. The interviews ranged widely, covering the executives’ views on government, politics, the media, and liberal reform, and provided the backbone for Ethics and Profits, a searing psychological study of business leaders’ troubled mind-set that Silk and Vogel published in 1976. According to the authors, the “Crisis of Confidence in American Business” (the book’s subtitle) unfolded along two planes. On one hand, opinion polls demonstrated conclusively that between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s, Americans lost faith that business leaders would “do the right thing” or “serve the public interest.” But just as important, Silk and Vogel showed that business leaders had also lost confidence in themselves. Though they retained a strong faith in the business system in general and remained convinced of their ability to successfully manage their firms, they believed they had lost the ability to communicate that success to the country. “Public acceptance of business has reached its lowest ebb in many a generation,” one executive complained. Added another: “We have been inept in the communication of ideas and the information that creates understanding among people.”8 In a decade marked by numerous “crises of confidence”—capped famously by President Jimmy Carter’s invocation of that phrase in his 1979 “malaise” speech—business leaders joined the chorus, protesting their impotence, voicelessness, and deep fear for the future.

The intense anger and pessimism that Silk and Vogel documented lay at the heart of the nearly paranoid declarations about an “attack on free enterprise.” Business leaders firmly believed that the public’s growing distrust, combined with their collective inability to defend themselves and promote the virtues of the capitalist system, had led directly to debilitating policy measures—including stiffer regulations and higher taxes. Such policies, they maintained, depressed profitability and caused economic stagnation, further decreasing the public’s confidence in the private sector. In this devastating vicious cycle, rising unemployment fueled the heavy hand of government, so business leaders’ sense of besiegement grew worse as economic performance slackened. As the robust growth of the 1960s gave way to rising inflation and declining productivity growth by 1970, trade association meetings and Rotary Club speeches hummed with despair over the future. After 1973, as the country suffered recession, severe price instability, energy crisis, and double-digit unemployment, these panicked warnings about the future of capitalism reached a fever pitch.

But such gnashing of teeth about existential threats to free enterprise was hardly new in the 1970s. Businesspeople have always complained about the government, particularly at moments of state expansion. The Conference Board itself formed in 1916 amid Progressive Era labor battles, when executives at large industrial corporations like General Electric bemoaned their low public approval and claimed that they risked losing control over their companies’ operations.9 Similarly, in the 1930s, Irénée du Pont rallied fellow industrialists to join his anti-Roosevelt American Liberty League by accosting the New Deal as “the Socialistic doctrine called by another name.”10 According to business historians like Alfred Chandler and Sanford Jacoby, American business leaders condemned government regulation in particularly fierce terms because of the peculiar birth order of managerial capitalism and the administrative state in the United States. Because big business developed in the late nineteenth century in the virtual absence of muscular bureaucratic regulation, employers developed a strong tradition of resisting state intrusion on their operations, and the persistence of such arguments after World War II reflected their long institutional memory.11 And ironically, despite this tradition of vehement protests, scholars have also demonstrated the degree to which business has historically prospered under the stabilizing influence of growth- and competition-oriented regulatory policies.12 Complaints about an assault on capitalism, in other words, have proved far from unusual and we should take them with a grain of salt.

Although couched in old-fashioned rhetoric, the crisis many business leaders articulated in the 1970s proved historically distinctive both in its causes and in its effects. To be sure, corporate executives and conservative politicians grossly exaggerated the threats business faced, just as du Pont had far overstated the “Socialistic” tendencies of the New Deal. Nonetheless, their feelings were genuine, largely because their anxiety stemmed directly from very real changes to the political and economic landscape in which business leaders operated. These broader transformations certainly did not augur the end of capitalism, but they did fundamentally unsettle the business world and fuel business leaders’ antistatist hysteria. On a policy level, the restructuring of the administrative state through the proliferation of social regulations altered the landscape of interest group politics and increased compliance costs and disclosure requirements for more heavily regulated firms. Politically, the shifting composition of Congress—from the disintegration of the Solid South to the arrival of liberal “Watergate babies” in 1975—upset longstanding alliances between corporate leaders and representatives. On a cultural level, a palpable wave of hostility toward all established institutions swept American politics in the wake of the counterculture, Vietnam, and later Watergate, compounding business’s crisis of confidence. Finally, very real shifts in global capitalism compounded business leaders’ angst as foreign competition threatened profits and inflationary supply shocks sapped capital.

The powerful and sincere notions, however hyperbolic, that these changes provoked had real and profound consequences because business leaders’ sense of panic directly sparked overt political action by an increasingly unified capitalist class. For most of the postwar period, business leaders had been loath to engage too directly in the political process. Some considered politics unseemly; others believed lobbying was a job best reserved for public relations specialists. In the early 1970s, however, longstanding political grievances reached a tipping point, as frenzied declarations of the “attack on free enterprise” drove many executives to overcome their reticence and inject themselves more forcefully into politics. At the Conference Board meetings that Silk and Vogel attended, one executive declared: “If you don’t know your senator on a first-name basis, you are not doing an adequate job for your shareholders.”13 During the 1970s, in response, individual firms dramatically escalated their direct lobbying, corporate PACs multiplied, and libertarian and conservative think tanks blossomed across the political landscape, funded largely through donations by successful businesspeople. In addition, as chapters 2 and 3 explore in greater detail, industry-specific and pan-business trade associations responded to the sense of an external threat to business by greatly expanding their memberships, budgets, lobbying prowess, and influence. Ultimately, this pan-industry mobilization formed an integral part of a conservative intellectual and political project to undermine the political ethos and institutional structures of the New Deal state. What made the politics of business in the 1970s unique, therefore, was not the substance of business leaders’ critiques but their effectiveness in mobilizing around them.

This chapter traces the political, economic, and cultural changes that combined to enflame business’s “crisis of confidence” and incite its political mobilization in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In the process, it suggests that this experience marked a departure from the early postwar years often described as one of “liberal consensus.” To be sure, many historians now challenge the notion that a general peace pervaded business-government relations in the twenty years following World War II, so the very term requires careful qualification. Traditionally, the “liberal consensus” framework argued that the intense class-oriented battles between labor and business of the Progressive and New Deal periods cooled down markedly after the war, when Cold War imperatives prompted both sides to unite around ideals of liberal democracy and the promise of mass consumption. As a result, each side moderated a little and accepted the other. Scholars who embrace this view point out that although organized labor reached the height of its power in the mid-1950s, when 35 percent of the workforce was unionized, the expulsion of communists from labor ranks and George Meany’s conservative leadership of the AFL-CIO represented concessions to business. At the same time, the Republican Party under Dwight Eisenhower resisted more conservative efforts to roll back the New Deal state. Despite Ike’s tepid actions on civil rights and blustery threats of “massive retaliation” in foreign policy, he made no effort to undermine the new social compact or Keynesian economics. Indeed, Eisenhower and his corporate allies—both Democrat and Republican—recognized the legitimacy of organized labor and the reality of social welfare, much to the consternation of conservatives like Robert Taft, Barry Goldwater, and, ultimately, Ronald Reagan.14

Recent scholarship, however, has convincingly demonstrated that many prominent business leaders never accepted New Deal–style liberalism and in fact campaigned actively and vehemently for its rollback from the 1930s onward. After the downfall of the American Liberty League in the early 1940s, for instance, recalcitrant organizations like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) retained their anti-Roosevelt mantle and argued publicly against New Deal programs like Social Security and the 1935 Wagner Act, under which the federal government formally recognized workers’ collective bargaining rights. Those groups also played a large, if not decisive, role in the passage—despite Harry Truman’s veto—of the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which scaled Wagner back and paved the way for “right-to-work” states.15 Organized labor likewise remained militant, confronting management through strikes and boycotts over issues like high consumer prices, factory relocations, and other intrusions on workers’ rights by employers.16 These conflicts between labor-liberalism and a profoundly conservative anti–New Deal impulse clearly strained at the boundaries of the supposed consensus.

Nevertheless, the persistence of conservative antistatism does not mean that we should reject entirely the claim that a measured truce pervaded business-government relations from the late 1940s through the mid-1960s. Although historians should not overstate the level of harmony among business leaders, labor leaders, and liberal politicians, the existence of dissent mattered less than the influence of the dissenters. After all, “consensus” need not imply that everyone agreed with each other all of the time but merely that the sharpest conflicts did not dominate the mainstream. The history of organized business groups exemplifies the point. Although the NAM and the Chamber of Commerce remained virulently antilabor and continued to rail against the New Deal, their role on the national political stage shrank remarkably after World War II. Indeed, their unflinching faith in self-correcting markets and staunch opposition to Keynesianism combined to minimize their influence. Rather, in the 1950s and 1960s, the “voice of business” in national politics largely emanated not from those organizations but rather from what political scientists dub “accommodationist” business associations like the Committee for Economic Development (CED) and the Business Advisory Council (BAC). Such organizations provided industrial expertise to government officials on such issues as war-industry management, reconversion, and economic planning, but they neither lobbied nor dictated the policy agenda. Although some historians, adopting a framework of corporate liberalism, have rightly suggested ways that such business groups shaped policy to their advantage behind the scenes, they remained subordinate to government and viewed themselves as such.17

To say that many corporate executives “accommodated” liberal Keynesianism and the general contours of the modern regulatory state does not mean that they were always happy about it, of course. Conflicts arose frequently over a variety of policy issues, including corporate taxes, racial integration in the workplace, price controls, and foreign trade. As a general rule, however, the leaders of accommodationist business groups kept their ideological rants to a minimum, and their counterparts at archconservative organizations found themselves largely on the outside looking in during the first few decades after World War II.18 This dynamic began to change, however, during the 1960s, as powerful political and economic forces converged to upset the institutional environment and destabilize that fragile consensus. In its place emerged the “crisis of confidence,” which would ultimately invert the power dynamics within the business community and create opportunities for conservative organizations to supplant the accommodationists and organize a broad-based movement in opposition to liberal policies.

BUSINESS AND THE POLITICS OF THE 1960s

Many Americans in the 1970s, no less than today, had a hard time taking seriously the idea that top corporate executives and the directors of national business associations suffered crippling fits of fear and doubt or that they constantly bemoaned their political and cultural impotence. The capitalist class, after all, included the wealthiest people in the country and their daily work affected millions of lives. What factories to open and close, what products to sell and for what price, and how much to pay employees? Such decisions touched workers and consumers, as well as their families, across the country and around the globe, making claims of weakness sound spurious, even silly. What’s more, any objective analysis of their political clout would conclude that these were intensely powerful men, able to gain an audience with senators, governors, and the president at their whim. Such access and influence lay simply beyond the imagination of regular people, even those (always an unfortunate minority) who engaged actively in the democratic process. As political scientist David Vogel put it (some years after his sleuthing for the Conference Board): “Through the middle of the 1960s, the political position of business certainly appeared to be a privileged one.”19 And yet by the latter years of that decade, these rich and powerful men collectively began to sweat. By the early 1970s, they had entered into a full-blown panic.

So what changed when the times were a-changin’?

The short answer is that those tumultuous years witnessed a fundamental political and economic restructuring. On the domestic front, the late 1960s saw the triumph of what scholars have called a “rights-conscious revolution” that expanded political battles beyond the traditional frameworks—labor versus business, rich versus poor—to include myriad interest groups organized around race, gender, ethnicity, religion, consumption, and environmental protection. For many business leaders, the most important consequence of this new type of politics was the proliferation of regulations designed to protect specific groups of people from the excesses of corporate capitalism. At the same time, the late 1960s witnessed the end of the extended period of growth and prosperity that the United States—particularly its manufacturing sector—had enjoyed since the end of World War II. Although practically no one openly suggested that the lauded “American Century” would soon come to an end, the stresses of renewed foreign competition from Germany and Japan, the strength of certain labor unions, and the maturation of traditional industries combined to place real pressure on corporate profits.20

The longer answer is that the fragile accord that business leaders had struck with the modern American state began to unravel, erratically and sometimes imperceptibly but significantly nonetheless. Despite widespread prosperity during most of the 1960s, many prominent business leaders began to feel increasingly isolated from the political power structure. Any such decline in their status or political importance was, of course, relative; wealthy industrialists remained very influential men. But compared with the halcyon days of Republican president Dwight Eisenhower and the 1950s, a growing number of executives felt more like outsiders to policy than they had before.

Politically, the sense of isolation that ultimately led to business’s crisis of confidence began with the election of Democrat John F. Kennedy in 1960. Although Kennedy had only superficial policy differences with his Republican opponent, Richard Nixon, the youthful Massachusetts senator struggled to convince business leaders that he shared their goals and vision. Partisan stereotypes played a role. Many business leaders agreed with investment banker Henry Alexander (chairman of Morgan Guaranty Trust Company, later J. P. Morgan & Co.), who described the Eisenhower administration as “a turn away from the direction of constantly more government intervention,” which had been the rule since 1933.21 What, he asked, would a Democratic restoration under Kennedy look like? For his part, Vice President Nixon fueled those fires during the 1960 campaign, warning business leaders that a Kennedy White House would find itself at the mercy of radical labor leaders, to whom it would owe its political fortunes. Moreover, many businesspeople interpreted Kennedy’s campaign promise to “get this country moving again” as a call for an inflationary economic policy that would hurt their bottom lines.22

On a personal level, Kennedy’s biography didn’t help matters. Many business leaders grumbled about this scion of privilege whose only post-navy career had been politics and who had never had to meet a payroll. According to journalist Hobart Rowan: “The average big businessman had a proper respect for Kennedy’s wealth, but regarded him as a rich man’s son who had no real understanding of the role of profit or other business problems.”23 Of course, Nixon had also practiced politics as a profession and had never made a payroll, and there was certainly no love lost between the East Coast business establishment and the child of middle-class Quakers from suburban California.24 But Nixon at least belonged to the GOP, party not only of Eisenhower but also of Nelson Rockefeller and, at least by common stereotype, the business community since the 1850s. While the national Democratic Party certainly catered to business interests—and historically depended on support from businesspeople—its longstanding links to populist politics, farmers, immigrants, and organized labor weakened any claim it could make to be the “business party.” Indeed, according to eminent business historian Herman Krooss, only three of the thirty-one businesspeople who donated more than $1,000 during the 1960 election gave to the Democratic Party.25

Kennedy wrestled with the charge that he was “antibusiness” throughout his brief presidency, despite his decision to appoint business-friendly conservatives to important cabinet positions and to marginalize liberal firebrands like Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and John Kenneth Galbraith when it came to economic policy.26 A minor but telling brouhaha involving Commerce Secretary Luther Hodges highlighted the fraught relations between top business leaders and the Democratic administration. A self-made textile factory owner from North Carolina, where he had also been governor, Hodges did not typify a “Kennedy liberal” and perhaps might have appeared as an earnest business ally. An early architect of the “New South,” he supported government-funded research and development and played an instrumental role in the construction of the Research Triangle Park in his home state. Like other sunbelt political entrepreneurs, Hodges worked to bring new business to the region, inaugurating a pattern of capital flight from North to South in the early postwar years that would bear tremendous fruit, in large part by recasting labor politics, by the 1970s and 1980s.27 Although Hodges believed strongly in investment and capitalistic growth, his regional and class allegiances as a populist southern Democrat complicated his interactions with businesspeople, especially northern industrialists. On a cultural level, he remained deeply hostile to what he perceived to be the privileged status of old-money, eastern establishment business elites. When Hodges assumed the reins at the Commerce Department in January 1961, that animosity quickly turned into a high-profile flare-up with the kings of large industrial firms and their major representative organization, the Business Advisory Council (BAC).

The BAC dated back to 1933, when Franklin Roosevelt formed it by executive order at the behest of his first commerce secretary, Daniel Roper. Formally lodged in the Commerce Department, the BAC consisted of approximately fifty chief executive officers from major industrial and financial corporations who provided free, unfettered economic advice for the secretary and, by extension, the president. According to the organization’s most prominent historian, Kim McQuaid, this “business cabinet” constituted “a quasi-public advisory agency that was in the government, but not of it.” That is, the member CEOs enjoyed direct access to the White House, but they also retained a large degree of institutional autonomy—they financed their own meetings and kept the minutes private. This is not to say that the BAC dictated policy: as an advisory body, the group could not lobby. In some cases, it proved instrumental, helping create and operate the National Recovery Administration of 1933–35, for instance. In others, the White House overruled its opinion, as with the Wagner and Social Security acts of 1935. From the high points of the New Deal through the 1950s, however, the BAC retained its privileged position within the Commerce Department as, in McQuaid’s phrase, “the most important forum for … compromise-minded managers” from the country’s big businesses, including titans like U.S. Steel and General Electric.28

Luther Hodges was not a big businessman and made clear up front that he wanted immediate changes at the BAC, including a more diversified membership that included small and midsized companies, greater regional variety, and a more explicit role for the commerce secretary in the group’s structure and operations. In addition, he wanted to reform the BAC’s traditions of autonomy and secrecy, citing the imperatives of transparency and democracy in a body officially lodged in the government. In short, Hodges envisioned an end to the BAC’s exalted, privileged status. In July 1961, after months of tense and often viciously personal wrangling between Hodges and the top brass at the BAC, the chief executives rejected the secretary’s proposals and instead voted to formally disaffiliate themselves from the Commerce Department. Dropping the term “Advisory” from their title, they became simply the Business Council, a private consortium of CEOs from large corporations dedicated to articulating their collective policy preferences to the government and the public. Kennedy worked feverishly to mend fences with the individual CEOs at the Business Council, distancing himself politically from Hodges in the process. Nonetheless, the face-off contributed to the president’s reputation as less than fully supportive of business.29

Less than a year after the Business Council bolted from the federal government, an even higher-profile showdown developed between Kennedy and major industrial leaders: the famous “steel crisis” of 1962. The steel industry had been central to the history of industrial political economy in the United States since Andrew Carnegie broke the Homestead strike in 1892. In the postwar period, the politics of prices for steel and wages for steelworkers led to a pitched confrontation in 1952 when the threat of a strike in the midst of the Korean War prompted Harry Truman to nationalize the steel industry, only to be overruled by the Supreme Court.30 Yet the federal government’s heavy involvement in labor-management relations in steel persisted. In 1959, during another fiery round of contract negotiations between steel companies and the United Steelworkers union, members of the Eisenhower administration (particularly Vice President Nixon) convinced the steel companies to accede to higher wages in the interest of labor peace and yet to keep the sale price of steel constant—absorbing the loss. Three years later, during yet another round of contract negotiations, the steel industry confronted a new president who had made price inflation enemy number one. According to wage-price guidelines issued by the Kennedy administration, unions had to demonstrate an increase in worker productivity to justify a pay raise, thus preventing companies from passing through higher labor costs into the price of an essential commodity. Using his leverage with the unions, Kennedy ensured minimal wage increases, and he fully expected the steel companies to fulfill their end of the bargain and keep prices down.

For Roger Blough, chairman of the United States Steel Corporation and chairman of the now independent Business Council, Kennedy’s imposition of wage-price guidelines and apparent coziness with the steel unions represented an intolerable intrusion on the industry’s ability to set its prices and remain profitable. In a face-to-face meeting in the Oval Office in April 1962, Blough handed Kennedy a memo—which he had already distributed to the press—announcing that U.S. Steel would raise its prices by 3.5 percent, effective immediately, despite the guidelines. Within hours, U.S. Steel’s major competitors, including Bethlehem, Republic, and Jones & Laughlin, announced similar price hikes. Faced with such intransigence, not to mention the real possibility of unpopular inflation stemming from the higher price of steel, John F. Kennedy briefly declared war on Roger Blough. Famously telling his staff that “steel men were sons of bitches,” the president launched a rhetorical and legal assault on “Big Steel” and, by implication, overprivileged corporations in general. Taking to the airwaves, Kennedy lambasted steel executives “whose pursuit of power and profit exceeds their sense of public responsibility” and who displayed “such utter contempt for the interests of 185 million Americans.”31 He didn’t mention Blough by name, but he didn’t have to: no one could doubt the object of Kennedy’s ire. At the same time, the U.S. Department of Justice, conveniently headed by Kennedy’s brother Robert, began to investigate whether Bethlehem Steel had colluded with U.S. Steel to raise its prices in violation of antitrust law. In the end, the public shaming and not-so-subtle threat of legal action worked. Blough rescinded U.S. Steel’s price increases, and Kennedy notched a public victory, but at a price. Distrust and discord between the Democratic president and important elements of the business community persisted, foreshadowing later clashes between liberals and business leaders over the politics of inflation in the 1970s.32

When Lyndon Johnson assumed the presidency upon Kennedy’s death in November 1963, business relations with the White House improved slightly but not enough to overcome the emerging partisan schism between the Democrats and many corporate leaders. As a skilled legislator with a long history of forging agreements among opposing groups, Johnson struck many businesspeople as more approachable than Kennedy had been. Unlike in 1960, when business support overwhelming went to Nixon, business partisanship was subdued in the 1964 election and corporate executives by and large backed Johnson against Barry Goldwater. (To be sure, the real “business candidate” in 1964 was New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, whom Goldwater defeated in the primaries on a wave of anti-establishment populist conservatism.)33 As president, Johnson worked hard to foster mutual understanding and common goals with business leaders. In January 1964, he invited members of the Business Council for dinner at the State Dining Room to hear a preview of the State of the Union Address. One executive gushed: “It’s the first time in our history that we’ve been invited to dine in the White House—it didn’t even happen under Ike!”34

Business’s honeymoon with Johnson was short-lived, however. The new president’s eager commitment to Great Society spending programs and reluctant escalation of the war in Vietnam strained the federal budget, yet he balked at pushing for higher taxes. Fiscally hawkish business leaders objected to the growing deficits and fretted over the possibility of inflation. In addition, many corporate leaders detected in Johnson the same partisan traits they had viewed suspiciously under Kennedy, including his sustained commitment to wage and price guidelines. As one administration staffer explained, many business leaders complained that the president was “always bashing big business but never bashing big labor.”35

THE STIRRINGS OF MOBILIZATION: PACs AND LOBBYING

During the Kennedy-Johnson years, increasing numbers of business leaders thus came to believe that the ship of state was sailing away without them. Asserting their collective influence over policy would require greater political infrastructure than the business community had traditionally employed. Although the highest-profile debates over business involved major industries like steel and macroeconomic questions of wages and prices, the institutions of collective action that ultimately permitted broad-scale business mobilization in fact emerged from specific debates in a different field: the medical profession. During the early 1960s, debates over the pharmaceutical and health insurance systems galvanized the medical community and prompted new forms of political organizing, campaign funding, and lobbying—tools that the broader business community would later appropriate.

As they would in the 1990s and 2000s, liberal proposals to regulate and reform the health care industry prompted a major conservative backlash in the 1960s. The reform movement involved two complementary planks: imposing stricter regulations on pharmaceutical products and providing government-run health insurance for elderly and poor Americans. In 1959, Senator Estes Kefauver (D-TN) launched a highly publicized investigation into the pharmaceutical industry in the wake of mounting concerns about high drug prices and investigations of price-fixing among drug manufacturers. Kefauver’s hearings led to a legislative push, propelled by widespread outcry over birth defects linked to the sedative thalidomide, that resulted in the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendment to the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which increased regulations and disclosure requirements on drug manufacturers. A few years later, congressional liberals successfully passed the Social Security Amendments of 1965, creating Medicare and Medicaid. Both reforms prompted vociferous objections by conservatives; indeed, lobbying from the pharmaceutical industry rendered Kefauver’s law significantly weaker than its backers had hoped. Critics of Medicare and Medicaid charged health insurance for the old and poor represented a treacherous slide toward the type of nationalized health care practiced in Western Europe, and those fiery protests united political conservatives in a vague battle cry against “socialized medicine.”36

The fiery political debates over national health insurance and pharmaceutical regulation prompted the American Medical Association (AMA) to form the first conservative—indeed, the first nonlabor—PAC in 1961 to raise money for candidates who opposed increased governmental regulation of and involvement in the medical profession. The creation of the AMA’s PAC marked a signal change in the national political landscape because the legal status of PACs remained ambiguous in the early 1960s. The 1907 Tillman Act, which barred corporate campaign contributions, and the 1943 Smith-Connally Act, which extended that prohibition to labor unions, still governed, but those laws did not specify whether those institutions could collect and redistribute funds that were freely given by individual employees or members (that is, money that did not come directly from their coffers). Beginning with the CIO’s PAC in 1943 (the first political action committee in the United States), trade unions relied on their political clout to evade legal issues. Corporate managers, on the other hand, adhered more strictly to the letter of the law but developed other strategies to funnel money to politicians. For example, many companies allowed employees to charge campaign activities to their corporate expense accounts; retained managers and staff on the payroll while they worked for campaigns; and offered pay raises to employees with the explicit understanding that they would donate the extra money to specific political candidates. Both companies and unions also evaded campaign finance laws by employing the same lawyers and public relations firms as candidates and then overpaying those vendors for legitimate services, effectively funneling money to campaigns. Such measures, while technically illegal, grew increasingly common as the costs of running campaigns increased with the spread of television in the 1950s and 1960s.37

Such evasive techniques remained far less efficient than aboveboard political action committees, so the AMA’s decision to form a PAC opened an important door to more coordinated corporate fund-raising, and it came at an opportune time. In the second half of the 1960s, many public affairs executives and professional Washington Representatives noted a clear shift in the congressional terrain in which they had previously operated quite comfortably. The increasingly liberal stance of non-southern Democrats on issues like civil rights and social welfare, as well as the consolidation of the Goldwater wing of the Republican Party at the expense of Northeast liberal Republicans, changed the constitution of each party’s caucus and led to a sea change in legislative strategy. Prior to this change, according to one insider, Washington Representatives had worked on specific issues with members of Congress they knew personally, and the most entrepreneurial used their contacts with committee chairmen or, in many cases, Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson, to great effect. Johnson’s departure for the vice presidency (and ultimately the White House) blocked off many of those inroads, and the increased push to weaken the power of committee chairs further destabilized the status quo. Corporate lobbyists in particular felt outgunned under the new dispensation. Many noted with dismay that their opponents in organized labor, because its campaign finance strategy matched its lobbying prowess, successfully targeted not only policymakers but also the composition of Congress.38

Following the AMA’s example, a handful of directors from the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) established the country’s first corporate PAC, the Business-Industry Political Action Committee (BIPAC) in August 1963. The group’s first president, Texan Robert Humphrey, left his position as the NAM’s public affairs director to dedicate himself full-time to running a freestanding organization that he felt would be better suited to influence campaigns without becoming bogged down in legislative minutiae. Despite BIPAC’s official independence, its original board members retained their affiliation with the NAM, and the group in its early years relied on significant seed money from existing business groups. Highly conscious of the potential legal snarls related to coordinating corporate campaign donations, the new organization retained well-heeled D.C. tax lawyers from the firm of Miller and Chevalier, who advised BIPAC to create a bifurcated organizational structure. On one side stood the educational arm, which could promote a “business” perspective in political debates through the media and in the workplace. The financing arm, on the other hand, would collect voluntary contributions from individual people, usually from within specific corporations, and redirect those funds to politicians.39

In the group’s early years, BIPAC leaders worked hard to establish credibility by stressing their reputations as chief executives from well-respected manufacturing firms, many of whom had been active in the NAM. Its board of directors grew quickly and, quite by design, included well-known heads of oil companies, utilities, and financial services firms. Moreover, BIPAC’s educational arm funded “political education” efforts, publishing a newsletter to explain the political process, the dynamics of specific local and national races, and the importance of voting, especially on “business” issues and for “business” candidates. According to Robert Humphrey, BIPAC aimed not to fund winners, necessarily, but to provide financial assistance to candidates with principled pro-business positions who found themselves in tight, competitive races. As a result, success came slowly; in 1964, for example, most of its candidates lost, including two Republican Senate candidates—Texas oil executive George H. W. Bush and Tennessee lawyer Howard Baker (running to replace the recently deceased Estes Kefauver). In the midterm elections of 1966, however, the group fared much better, and its support contributed to major conservative victories. Moreover, although BIPAC involved itself primarily with federal elections, its leaders encouraged business activism at the state level as well. Although “political power ha[d] shifted from the states and localities to Washington” since the 1930s, a BIPAC report argued, “electing a fiscally-minded state legislature [remained] vital to the economy of the state and the nation.”40

Although BIPAC’s message resonated with many conservative businesspeople, the organization struggled during the 1960s because of persistent uncertainty about the legality of political action committees. That ambiguity was only resolved in 1975 when the Federal Election Commission (FEC)—created by Congress to enforce new campaign finance laws passed in 1971 and 1974—issued its Sun Oil decision, officially sanctioning corporate PACs, whose numbers skyrocketed in the next few years. That growth was particularly stark in comparison with the number of labor PACs. Between 1974 and 1978, the number of business PACs shot up from 89 to 784, while labor PACs increased by only 16, from 201 to 217. The total number of corporate PACs peaked at approximately 1,800 in the late 1980s and settled around 1,600 from the mid-1990s to 2012. Prior to the reforms of the mid-1970s, however, BIPAC largely remained a lone voice in the wilderness.41

Even as Kennedy-Johnson policies propelled the drive for more formalized corporate campaign financing, the changing mechanics of business-government relations in the 1960s likewise bolstered business leaders’ clamor for greater institutional power and collective action. Although Johnson tried to appear friendly to business concerns—touting fiscal discipline, noninflationary growth, and concern for the international balance of payments—his particular style ultimately confirmed corporate leaders’ sense of isolation from the inner circles of power. On legislation ranging from free trade to public housing to taxes, Johnson distinguished himself by making strategic use of ad hoc committees of business leaders to promote his policies. In 1967, leading industrialists formed the Emergency Committee for American Trade, an ostensibly independent group that promoted Johnson’s position against trade quotas. The president also pushed the Business Council to create an offshoot organization called the Business-Government Relations Council to facilitate information sharing among lobbyists for large firms. That new group, according to the administration, existed “solely for liaison with the federal government and [would] not take policy stands on political issues.” Although such institutions brought business leaders more directly into the political process, they also highlighted their inherent weakness: business provided advice when called upon, but the politicians set the agenda.42

Business’s continued reliance on firm-specific Washington Representatives ironically exacerbated this growing sense of isolation. Wealthy corporations had long relied on professional public affairs firms such as the prestigious Hill and Knowlton, founded as a “corporate publicity” office in 1927, as for-hire mouthpieces both to the consuming public and, especially since World War II, to government officials and policymakers. But in addition to those hired guns, large companies also retained in-house experts, many of whom registered as lobbyists under the 1946 Federal Regulation of Lobbying Act, which required anyone who was paid primarily to influence legislation to register with Congress and report all lobbying income. Although the total number of Washington Representatives increased steadily during the 1960s, before exploding in the 1970s and 1980s, the vast majority of companies could not afford such tailor-made representation and instead relied on trade associations to defend their interests. Yet even firms that employed in-house lobbyists engaged in precious little collaboration or collective work. Some Washington Representatives skillfully forged contacts with legislators and won specific favors for their firms—a subsidy here, a government contract there—while others proved notably ineffective. But successful or not, company-specific lobbyists focused narrowly on their employers’ needs, not the concerns of the broader business community.43

Amid the contentious politics of the 1960s, however, business leaders sought opportunities to bring their lobbyists together. For example, in late 1964, Henry Ford II (CEO of the eponymous car maker) learned that the Johnson administration intended to release a report that criticized the private retirement system and made far-reaching recommendations for pension reform. Ford instructed his Washington Representative to form a committee of lobbyists from fifty companies to generate broad-based industry opposition. To chair that committee, Ford appointed Sidney Weinberg, a senior partner at Goldman Sachs and member of many corporate boards, including that of the Ford Motor Company (his nickname was “Mr. Wall Street”). Under Weinberg’s leadership, the Washington Pension Report Group grew to include 125 companies whose lobbyists paid numerous visits to government officials and members of Congress, presenting a unified front against the pension reform recommendations. This brief episode provided a glimpse of the possibility that broad-based collaboration among lobbyists might bring, but it also highlighted the challenges involved. According to Ford’s Washington Representative, Weinberg’s leadership proved essential to holding the committee together. When Weinberg died in the summer of 1969, the committee faltered, and liberal politicians led by Jacob Javits ultimately pushed through the public pension reforms known as the Employment Retirement Income Security Act, or ERISA, in 1974.44

Many top executives interpreted the dissolution of the Pension Report Group as a clear signal that their status in Washington politics remained perilously fragile. Although that group, along with the Johnson administration’s ad hoc business committees and the Business Council, would later provide vital institutional grounding for the Business Roundtable, its fate reinforced a declension narrative during the late 1960s. Washington Representatives and trade associations, business leaders remarked, had simply stopped getting the job done. Firm- and industry-specific strategies could successfully win particular favors, but they had little effect against broader policy initiatives—whether on pension reform, taxes and budgets, wage-price guidelines, or national health care. Given the shifting political sands in Congress and public support for policy proposals that seemed to cut against core business interests, disorganized and haphazard lobbying looked increasingly powerless. By the end of the 1960s, creeping inflation and weak productivity growth combined with a hostile political culture to undermine business leaders’ confidence. But those economic and political factors provided only part of the context. Adding essential fuel to the fire, business leaders noted with chagrin their painful inability to halt what they saw as an avalanche of debilitating new government rules restricting business affairs—known collectively as “social regulations.”

STRUCTURAL CHANGES, STRUCTURAL CONSEQUENCES

While partisan tensions and conflicts over labor and health care policy certainly captured business leaders’ attention in the first half of the 1960s, a combination of policy developments and destabilizing macroeconomic changes came to dominate their concerns by the 1970s and underscore the growth of business’s crisis of confidence. On a policy level, the American regulatory state underwent a historic reconfiguration that enflamed political passions among many businesspeople. At the same time, the deteriorating national economy and the decline of America’s manufacturing dominance contributed to the growing sense of crisis within the business community. For many corporate leaders, these two phenomena fit hand in glove, and a growing number argued with mounting fervor that liberal economic policies were wreaking havoc on the national economy and business’s future.

Between roughly 1965 and 1975, a new regulatory regime succeeded—although it did not always supplant—the systems put in place first during the Progressive Era and then by the New Deal. Both earlier reform moments had created powerful federal institutions to fetter the operations of private market actors, but each emerged in response to the specific problems of its time. Between the turn of the twentieth century and World War I, Progressive reformers reacted to the economic instabilities generated by rapid industrialization and the rise of large corporations with regulations designed to manage competition and hold large institutions accountable to the principles of democracy. A generation later, during the Great Depression, the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations incorporated various regulatory impulses into a regime aimed fundamentally at navigating the wild vicissitudes of a failing economy. Government bodies like the Civil Aeronautics Board and the Interstate Commerce Commission (established in 1887 but expanded in the 1930s to regulate trucking and busing as well as railroads) created stable markets by restricting access and entry, setting prices and routes, and otherwise curtailing free competition. At the same time, the Securities and Exchange Commission provided stability for investors by promoting transparency in the financial community.45

In the postwar years, however, the turmoil of the early industrial period had long since settled and memories of the Depression began to fade. A new age, marked by industrial maturity and economic prosperity, bred a new critique of the existing regulatory structures, particularly among political activists who claimed to speak for “the public interest.” Intellectually linked to the New Left, this growing movement argued that the Progressive and New Deal regulatory regimes served business interests at the expense of “the public.” The federal government, public interest activists claimed, had become little more than a tool of privileged interests for preserving their own profits and protecting their industries from competition. Such critiques, while certainly not new, galvanized a broad coalition of neoprogressive reformers to lobby for new laws to protect people from business. By the mid-1960s, public interest activism generated new legislation ranging from equal employment (an outgrowth of the civil rights laws of 1964 and 1965) to consumer and environmental protection, from the Kefauver-Harris Amendment that strengthened the Food and Drug Administration in 1962 to the National Highway Safety Act of 1966 and the Air Quality Act of 1967. During the Nixon administration, the public interest movement reached the height of its influence, shepherding the creation of omnibus new federal bodies like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), which generated myriad new rules on everything from chemical emissions to workplace safety requirements.46

Thus by the late 1960s, the dominant thrust of regulatory politics in the United States had shifted from protecting a range of interests from business abuses, especially other businesses, to protecting people from business. Although most New Deal and Progressive Era policies had constituted “economic regulation,” the public interest movement concentrated far more on “social regulations.” These two forms were vitally different. Economic regulations governed economic behavior—the things companies did to make money—by restricting entry, prices, and so on. Social regulations, on the other hand, targeted what economists call the “externalities” of doing business—negative spillovers of economic activity whose costs are borne by society at large, such as pollution, labor injustice, and racism. By design, the industry-specific regulations of the earlier periods provided advantages for certain companies and industries over others; the new social regulations, by contrast, generally increased compliance burdens across all firms and industries.

The explosion of new social regulations in the late 1960s aroused business’s ire in large part because they thwarted the traditional power dynamics of regulatory governance. Both the environmental and consumer movements cut their teeth at the state level, championing legislation to establish independent regulatory commissions. However, by the early 1970s, their efforts turned squarely to the federal government and to specific laws that adopted a far stricter model of regulation. Environmental activists, for example, bemoaned the fact that state regulatory commissions not only suffered severe staff shortages but also frequently saw their memberships overrun by representatives of the very industries the agencies set out to regulate. The practice of “regulatory capture,” observed as far back as the 1880s, seemed to confirm the institutional power of entrenched minority interests over the public good. To confront this dynamic, reformers increasingly pushed reforms that centralized regulatory authority in specific administrators who answered directly to the president, who faced public accountability through the electoral process. The 1970 amendments to the 1963 Clean Air Act, for example, aggressively shifted the onus of environmental regulation from the states to the federal government, empowered a single administrator to enforce its provisions, and codified specific regulatory requirements in law. Critics branded such provisions “command-and-control” regulation, but proponents argued that only this type of regulation could permit the public interest to overcome the influence of powerful businesses and industries. According to political scientists Richard Harris and Sidney Milkis, the command-and-control regime aimed “specifically to avoid bureaucratic discretion and undue industry influence in the administrative process.” The centralization of environmental and consumer protection thus marked a deliberate attempt to reduce the sway of the regulated over the regulators.47

New social regulations represented an affront to business not only through their procedural mechanism, which certainly increased their effectiveness, but also through their spirit, which many corporate leaders interpreted as an affront to their integrity. In October 1972, the chairman of the Council of Better Business Bureaus (BBB), Elisha Gray, clearly expressed the business community’s widespread umbrage during a Business Council meeting. The council members, all chief executives at the country’s largest industrial, commercial, and financial firms, had assembled for their twice-yearly retreat weekend in Hot Springs, Virginia, where Gray took the opportunity to depict the rapid uptick in laws purported to protect consumers since the late 1950s. “Whereas none of us would quarrel with some of the earlier business standards … such as the Child Labor Law,” he explained, “we have every reason to be alarmed at … some of the more recent laws [that] begin to cut to the very essence of the free enterprise system … by the removal of incentives[,] … restriction of design and product possibilities … [and] the usurping by government agencies of the function of our customer relations.” As the head of a private organization explicitly dedicated to monitoring corporate behavior and preserving the good name (and profitability) of socially responsible firms, the BBB chairman argued that social regulations intruded directly on that prerogative and portended something far more sinister. At the rate they were going, Gray warned, the political forces behind the new laws threatened to “dismantle the free enterprise system in the next ten years.”48

In the early 1970s, Elisha Gray’s dire prediction was as commonplace as it was hyperbolic. Although jeremiads about the coming demise of “free enterprise” had echoed across corporate conference centers for years, the new social regulatory regime appeared to provide specific evidence of a fundamental realignment that both reinforced business leaders’ sense of their waning political influence and created significant cost pressures at a time companies could least afford them. After twenty-five years of nearly unquestioned manufacturing dominance, American firms saw their grip on global trade slip in the late 1960s amid the revival of foreign competition, especially from Japan and Germany. Moreover, the after-tax profit rate (for nonfinancial firms) hit a peak in 1965 that it would never see again.49 By the 1970s, this crisis of profitability morphed into a more general economic contraction, made worse by rising inflation. Productivity growth rates fell by half, even as real wages stagnated and real GDP per capita, which had increased by 35 percent under Kennedy and Johnson, rose by a paltry 12 percent under Nixon and Ford. In 1971, the United States clocked a trade deficit in merchandise—Americans bought more from than they sold to the world—for the first time since the 1890s. The following year saw the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of international monetary policy, which regulated worldwide capital flows and relied on the dominance of the dollar, dealing a major blow to American economic prestige. Dependable growth gave way to a series of recessions—in 1969–70, 1973–75, 1980, and 1981–82—each more severe than the last and typically dubbed “the worst since the Great Depression.” At the same time, price inflation accelerated after 1965 through a combination of deficit spending and monetary mismanagement, punctuated cruelly by severe supply shocks, particularly in energy.50

The deteriorating economy weighed heavily on the minds of business executives. Although many recognized the growing threat from foreign competitors, most prominent corporate leaders argued that American business could easily remain dominant in global manufacturing so long as domestic policies favored continued productivity growth. According to a NAM brochure, the “U.S. standard of living depends directly on a high level of productivity … [in order] to pay wages far above those of other countries [and] stay competitive in world markets.” Through the mid-1970s, therefore, politically active business leaders trained their sights on the threats to profits and productivity that emerged from trade barriers, as well as labor and regulatory policies, and far less on the changing international context as such.51

To make the case against liberal economic policies clear, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce sent its in-house economist Carl Madden to Congress to provide the “business” perspective on the 1970 “Economic Report of the President” prepared by Richard Nixon’s Council of Economic Advisors. Madden, a tall, portly man who had formerly worked as the dean of business at Lehigh University, grumbled to the assembled members of the Joint Economic Committee that, contrary to the popular view, the late 1960s had represented anything but a period of peace, love, and prosperity. Rather, he explained, the Johnson administration’s rampant federal spending had left “an unhappy legacy … of unrealized full-employment budget surpluses, escalating government deficits, and accelerating inflation.” Despite the “loose rhetoric … of affluence and abundance” that liberal policymakers boasted of, America at the dawn of the 1970s was “not nearly so affluent as some have appeared to believe,” Madden warned.52

Industrial leaders like Chicagoan Pete Venema, chairman of the NAM in 1972, also read the macroeconomic tea leaves as an indictment of existing domestic policy. Venema, like many executives of his generation, had risen from a middle-class background to excel in college; in 1932 he earned a chemical engineering degree at Armour, which later became Illinois Institute of Technology. Shortly thereafter he began a lifelong career at Universal Oil Products Company of Illinois, where he worked his way up from the pilot plant division through the patent department and then to executive status, leaving only temporarily to earn a law degree from Georgetown in 1942. In 1955 he became Universal’s chairman of the board and chief executive officer, and in later years he distinguished himself as president of his alma mater and a powerful spokesman for the NAM. Addressing fellow executives at an industrial relations conference, Venema bemoaned the dire state of American manufacturing, which faced “[h]igh costs for labor and material, backbreaking tax loads … an aging industrial plant … [and] trade barriers which inhibit our competitiveness in foreign markets.” The inevitable result, Venema predicted all too correctly, was that American industry would soon find itself “being outproduced and outcompeted by almost every industrial nation in the free world.”53

Corporate leaders like Venema and business-minded economists like Madden argued that faced with such economic instability, American corporations could ill afford the mounting regulatory compliance costs that new social regulations—from the EPA and OSHA to consumer product safety and measures to protect striking workers—would create. Although business handwringing about liberal policies toward labor and regulation had formed a mainstay of political discourse for generations, these men’s vitriolic attacks gained rhetorical potency as the economic vitality of the postwar period slipped away.

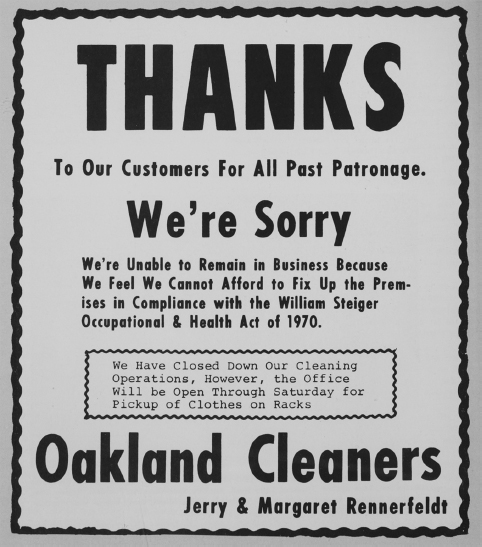

Figure 1.1. This sign, reprinted in the Chamber of Commerce’s newsletter in May 1972, captured the persistent anxiety among many businesspeople that excessive federal regulation—especially government agencies like OSHA and the EPA—would drive small companies out of business. Courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library.

At the same time, few if any business executives in the early 1970s accurately predicted America’s economic future—including the globalization of production and distribution, not least through advances in communication technology, and the rapid rise of the financial services industry. Although some theorists have claimed that business leaders responded to an acute crisis of capitalism in the late 1970s by mobilizing politically to enact a neoliberal takeover of the state, such arguments miss the chronology: business’s mobilization started well before the contours of the crisis in capitalism became apparent and in fact aimed to prevent the evisceration of domestic manufacturing. Economic insecurity and spe cific policy shifts thus laid a vital foundation for the business community’s political mobilization, but by themselves proved insufficient. A different set of factors—less quantifiable but equally vital—manifested on a psychological and cultural level within the business community and played an essential role in pushing business’s crisis of confidence to its breaking point.54

THE CULTURAL ASSAULT

Businessmen are people, too. While they might often wish to present themselves as unemotional, hyper-rational, nearly robotic decision makers—and indeed certain economic models suggest as much—in reality, major corporations as well as mom and pop stores are all run by human beings, with the virtues and failings that we all possess. Despite the wealth, success, and generally quite well-developed egos of the men who ran America’s largest firms and top business associations in the 1960s, they still had very human desires to be validated and appreciated. So while partisan politics, structural policy change, and real economic uncertainty underlay corporate leaders’ political mobilization, the stark rise in public antagonism to business as a social institution provided the final straw.

For many businesspeople, the increase in social regulations provided clear evidence of a cultural turn. In the mid-1960s, pollsters calculated that more than half of Americans expressed “a great deal of confidence” in the leaders of major companies, a record high for the modern polling era. But by the early 1970s, only 28 percent indicated such support, and after Watergate and the 1975 recession, the Harris polling company put the figure at 15 percent.55 Reflecting back in 1976, pollster Daniel Yankelovich, whose firm monitored public attitudes, concluded that social regulations since the mid-1960s had arisen directly as a consequence of that drop in public confidence. “Without the mistrust,” according to Yankelovich, “we would have had regulations, but [they] would have been ones in which both the business sector … and the political sector entered into a civil dialogue, both sides contributing, and reaching the kind of creative compromise for which our polity is famous.”56

Yankelovich was only partly correct, since the boom in social regulations had actually begun with consumer protection and equal employment laws in the early to mid-1960s when business—even big business—boasted historically high public approval rates. In reality, the push for environmental, consumer, and workplace regulations grew from a confluence of historical factors, including the increasingly partisan composition of Congress, the proliferation of new types of knowledge about risk and prevention, and rising expectations born of the general prosperity. Nonetheless, Yankelovich’s analysis reaffirmed a central narrative that business leaders seized on, linking the new regulatory order to business’s collective inability to prove its mettle to the public. At the 1975 annual meeting of the Business Roundtable, Alcoa chairman John Harper explained the link clearly. “On the question of whether or not the typical big company is above the law, or whether inflation is caused by business making too much profits, or whether companies tell the truth in advertising, [public opinion] was fairly heavily against business,” the chief of the aluminum powerhouse declared. In a democracy, Harper continued, “what the public thinks … has a decided effect on the kind of legislation that comes out of Congress.”57

But as Harper well knew, public opinion by itself did not beget policy; organized interest groups played a vital role in shepherding legislation through Congress. The most important factor in the rise of new social regulations had been the newfound strength of the organized public interest movement, the myriad associations of lawyers, activists, students, and politicians who came to epitomize the sum of all of business’s fears. Indeed, many business executives believed that a fundamental moral critique lay embedded in the public interest movement’s activism. Through their mere choice of words, self-described defenders of the “public” interest implicitly condemned the “private” sector for its inability to protect consumers, citizens, and the environment. And no one person typified that animus more than a young lawyer named Ralph Nader.

Nader first rose to national attention in 1965 when he published Unsafe at Any Speed, a stinging condemnation of “designed-in” flaws in automobiles that gravely endangered drivers and passengers. The American business community famously got off on the wrong foot with Nader when General Motors hired a private investigator to dig up dirt on the consumer advocate’s personal life in the hope of smearing his image. The ham-handed plan backfired spectacularly when the public learned about it. GM ate crow, and the resulting legal settlement helped Nader establish a vast institutional infrastructure to expand his activism and public influence. In short order, Nader rode his newfound celebrity as the little guy who challenged the corporate giants to a string of legislative victories, including, quite prominently, the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966.58

Nader’s star continued to rise throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 1972, a Louis Harris poll found that 64 percent of Americans agreed with the statement: “Nader’s efforts go a long way toward improving the quality and standards of the products and services the American people receive.” At the same time, only 5 percent agreed that “Nader is a troublemaker who is against the free enterprise system.” Within that 5 percent, however, lay a disproportionate number of corporate leaders and their ideological allies in conservative organizations. The American Conservative Union accused Nader of running a “hate-business campaign” that represented “in essence … a movement for far stricter, often absolute regulation of business and market activity.” John Post, a conservative lawyer from Texas and the first paid staffer for the Business Roundtable when it was founded in 1972, years later described Nader as “riding tall, wide, and handsome” in the 1970s. According to Post, a gaggle of journalists and cameramen would crowd Nader’s press conferences, but when Post emerged afterward to provide the Business Roundtable’s opposing view, “nobody filmed it.” Against Nader’s celebrity, business felt it couldn’t get a word in edgewise. Such political and cultural exclusion convinced many corporate leaders that a new political order was afoot.59

If the strength of the public interest movement convinced business leaders that the public was turning against them, numerous opinion polls bore out that conclusion. By mid-1975, according to Gallup, Americans had less confidence in “big business” than in any other major national institution. At the same time, however, the public mood in the mid-1970s had also soured on everything, from government to organized religion to the military. Nevertheless, Republican pollster Robert Teeter, who worked for President Gerald Ford (and later Reagan and both Bushes), concluded that the decline in public support for business was steadier and deeper than for other groups. While 34 percent of the public trusted big business, 38 percent of Americans had confidence in organized labor, 40 percent in Congress, 58 percent in the military, and 68 percent in organized religion.60

Scholars have long noted the widespread public pessimism that marked American culture in the 1970s, but it remains an underanalyzed phenomenon. In the space of a few short years, the ebullient spirit embodied by civil rights protestors, antiwar demonstrators, and other liberal groups gave way nearly entirely to what author Tom Wolfe called the “Me Decade”—a period of self-loathing narcissism. For filmgoers, one of the period’s most iconic moments came in 1976’s Network, in which newsman Howard Beale suffers a nervous breakdown at the hands of the soulless corporate television machine and gets the whole country screaming: “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!”61

What underlay such angst? Historian Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism, published in 1979, argued that the roots of America’s despair lay in structural factors related to capitalist individualism and the spread of consumer culture since World War II. In the late 1960s, for example, New Left activists expressly condemned corporate greed and the alleged power of the military-industrial complex, lending a profoundly anticorporate and often anticapitalist strain to antiwar protests, such as the firebombing of Bank of America branches in 1970. Moreover, widespread disgust over the role of corporate political slush funds, exposed through the Watergate scandal, as well as real product safety controversies likewise fueled the flames. Finally, some scholars have submitted that rising income inequality, which began with the economic crisis of the early 1970s and intensified through policy decisions in the Carter and Reagan administrations, has accounted for the long-term decline in Americans’ confidence in nearly all major institutions. In all its manifestations, the malaise that beset American culture no doubt contributed to the public’s declining trust in business leaders.62

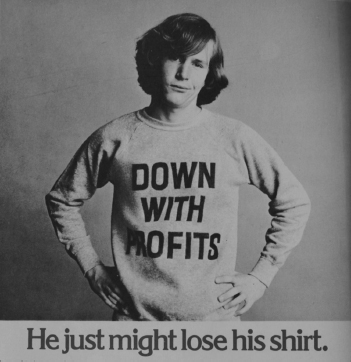

Although Americans in general became more pessimistic in the mid-1970s, corporate leaders almost certainly overreacted to a handful of choice opinion polls in their diagnosis of a widespread assault. Yet even if their evidence did not represent society as a whole, it provided powerful ammunition for concerted action, and business leaders took those declining poll numbers seriously. In corporate boardrooms and conference centers across the country, their public speeches and private correspondence overflowed with a run of depressing statistics. Many complained—as they had in the 1880s, 1910s, 1930s, and whenever reformers had challenged the status quo—that the public was terribly ignorant and misinformed. “People don’t have much sympathy or understanding for corporations’ needs for profits,” Alcoa’s John Harper explained, “when prices are mounting and they are feeling the pinch.” Even as corporate profits declined in the 1970s, executives knew that they often looked like profiteers. Speaking to the American Gas Association in October 1973, the NAM’s chairman, Burt Raynes of Rohr Industries, explained that the “average American, not just students, thinks that business makes 28 percent profit on every dollar of sales. And all of us in this room, I think, are quite aware that the actual percentage on sales is closer to 4-1/2 percent.” Such misinformation manifested in popular sloganeering, such as the sweatshirt in figure 1.2. Little wonder business seemed under attack.63

Moreover, many executives concluded that the public’s negativity extended beyond profits and literally threatened the existence of their firms. One of the most outspoken CEOs on this matter was AT&T chief John deButts, the man at the heart of one of the largest antitrust lawsuits in American history. Born in Greensboro, North Carolina, deButts earned an electrical engineering degree at Virginia Military Institute before starting a long career with AT&T, where he rose triumphantly through the ranks. As executive vice president and vice chairman of the board in the 1960s, he had a front-row seat to the intense wrangling between the telecommunications giant and the antitrust division of the U.S. Department of Justice. Antitrust investigations ultimately led to a formal suit in 1974, by which time deButts had become CEO, and ultimately to the breakup of the “Ma Bell” system in 1984. Years of management experience convinced deButts that poor public relations had been at the heart of the accusations of monopoly that AT&T faced. The company’s problems, he insisted, stemmed from a Congress and a Department of Justice who “do not ‘hear’ what you have to tell them because they are committed to the idea that the company is too big, is beyond regulation, and should—for some philosophical or ideological reason—be cut down to size.” Appealing for help to a public relations expert in 1967, he bemoaned, “How do I get those government people to hear me—not just listen to me?”64

Figure 1.2. Business leaders in the early 1970s worried that many Americans lacked faith in the free enterprise system and its basic tenets, such as the profit motive. In this July 1973 ad from the Chamber of Commerce’s newspaper, the business association chastised the young man pictured for failing to see that “profit is an incentive to beat the competition with new and better products,” including the very sweatshirt he was wearing. Courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library.

In 1975, still fighting the Justice Department’s suit, deButts commissioned a massive study of large firms’ public image, which concluded that antibusiness bias ran rampant in the media, not just among journalists but in popular entertainment as well. As deButts summarized: “By television’s account, the executive suite is, for the most part, populated by stuffed shirts and scheming scoundrels, both types insensitive to the higher things in life and driven by nothing so much as a barely disguised greed.” An anonymous executive echoed the sentiment to David Vogel and Leonard Silk at the Conference Board meetings in 1975: “One little smirk or crack on the Tonight Show biases the opinions of millions of Americans.” Such treatment, deButts concluded, explained why “poll after poll confirms a steady growth in public skepticism with respect to the earnestness with which business pursues its professed aim of service to the public.”65

This antibusiness bias from the media and Hollywood, not new but perhaps more visible in the early 1970s, puzzled many business leaders. Why, they asked, were agents of the news and entertainment industries so hostile to business and profit when they themselves worked for large private corporations? Drawing on the work of social and political theorists, some business leaders came to believe that the answer lay in a profound and growing disconnect between the values of free enterprise and the country’s dominant mind-set. Scorn for business certainly shaped the work of journalists and entertainers, business leaders believed, but its roots lay far deeper in national culture.