A New Life for Old Lobbies

According to the Soviet social science textbook ObshchestvoVedeniye, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce determines “the political course of the United States.”

—Richard L. Lesher, president, Chamber of Commerce of the United States, April 1976

IN SEPTEMBER 1976, during the brief window between the hoopla surrounding the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence and the hotly contested presidential election in which Jimmy Carter ran Gerald Ford out of office, the 108-member board of directors of the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) held a meeting in Colorado Springs to debate nothing less than the future of their eighty-year-old organization. Three months earlier, the NAM’s president, Doug Kenna, had triumphantly announced an agreement to merge with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and create the “National Association for Commerce and Industry.” The combined strength of this proposed super-lobby would eliminate organizational “redundancy” and streamline the NAM’s and the Chamber’s central mission: to shape business-related legislation and to provide a mouthpiece for the united voice of the entire business community. Despite the merriment surrounding America’s 200th birthday, the country’s economic future looked especially bleak in 1976. Productivity, profit, and employment rates had all declined in recent years, and inflation and the public’s animus toward business were up. Combining the forces of the two stalwarts of American industry would at long last, according to Chamber of Commerce president Richard Lesher, put the business community in a position to combat the “growing bias in this country against the private sector.”1

The proposed merger of the NAM and the Chamber emerged from the widespread clamor for businesspeople to take collective action in response to the political perils they believed they faced. Businesspeople, according to an oft-cited refrain, had to learn the political lessons that labor had used to such success in the decades since the New Deal and engage in national legislative debates and policymaking more directly and concretely. By the early 1970s, corporate leaders broadly agreed that on issues from economic planning to social regulation, business simply found itself outfoxed at every turn. Just as labor’s successful use of political action committees had helped inspire the creation of the Business-Industry Political Action Committee (BIPAC) in the early 1960s, so too did the merger of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1955 provide a model for joining the country’s largest employers’ associations together in one institution. Political power, business leaders and their political allies believed, had to be cultivated, and unity begat strength. As one Republican congressman sympathetic to the NAM-Chamber merger wrote: “Without political clout, no legislative agenda can be possible.”2 Committed to institutional change, business activists tapped into a long history of strategic borrowing from their political opponents; the immediate pressure of their “crisis of confidence” helped them overcome institutional inertia and adopt a reformist agenda.

As vehicles for a united, pan-business political offensive, the leaders of the NAM and the Chamber believed that their size, experience, and diversity of membership gave them a unique advantage that a merger would only strengthen. Each association had a long history that dated to the Progressive Era (the NAM was founded in 1895; the Chamber in 1912), and each boasted small companies as well as Fortune 500 corporations on its roster. Of the two, the NAM was considerably smaller and somewhat more focused, comprising 13,000 member firms predominantly from the manufacturing, construction, and extractive industries, as well as a number of financial institutions. The 100,000-member Chamber of Commerce, the self-described voice of “Main Street” commercial interests, comprised service and manufacturing companies—including nearly all NAM members—as well as professional organizations, local and state chambers of commerce, and trade associations. Although leaders of both groups stressed that approximately 80 percent of their members were small companies, both also represented the nation’s largest industrial and financial services corporations, which tended to pay higher dues and exerted disproportionate influence on policy.3

Yet despite overlapping memberships, shared political goals, and the high hopes of their leaders, the proposed merger fell apart when the NAM’s board of directors voted it down. Although NAM president Kenna had promised that manufacturers would make up 80 percent of the combined organization’s board of directors and that “no effort would be made to force together state manufacturing associations with state chambers of commerce in individual states,” board members worried that integration with the Chamber would inevitably shift focus away from manufacturing interests. As the president of a small electric company opined, “NAM is a manufacturing oriented organization today; however, what will it be after the merger?” Yet even in failure, the effort to create a union between these two powerhouses testified to the powerful drive for a renewed political offensive as business’s crisis of confidence reached its peak in the mid-1970s. Although the NAM board ultimately placed industrial solidarity over pan-business unity, the merger had only been conceivable in the first place because both organizations had recently undergone a profound convergence of organizational structure and political strategy. Indeed, in the years leading up to the failed merger, these one-time dinosaurs of organized business had reinvented themselves by deliberately expanding beyond their historic functions to become dominant forces in national politics.4

The institutional developments at the NAM and the Chamber—the new life breathed into these old lobbies—grew directly from the political and economic upheaval of the late 1960s and early 1970s and paved the way for effective pan-business lobbying in the years ahead. The tumultuous 1960s had altered the landscape of Congress and party politics, particularly through the rise of public interest liberalism and its demands for greater federal intervention with regard to employment equality, consumer and worker protection, and environmental stewardship. The civil rights movement ended one-party rule in the South, creating a growing number of contested congressional races, and the Republican Party shifted further to the right on economic and social welfare issues. Congressional reforms, particularly the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, reduced the power of committee chairs and opened Washington to a barrage of interest group activists, lobbyists, and campaign funders. And finally, federal election reforms and the legalization of political action committees fundamentally changed the financing structure of congressional campaigns and the possibilities for various interests to shape policy.5

In this new political context, business leaders at the NAM and the Chamber refashioned their public image, refined their approaches to lobbying, and broadened their policy prescriptions. Maintaining their traditional focus on labor power and government “interference” in the market, they organized around issues like wage-price controls, the Davis-Bacon Act, and the minimum wage. At the same time, they expanded their horizons to reflect the new policy debates, inveighing against the proliferation of environmental protections and consumer product safety laws, and in particular against the expansion of federal regulatory authority through agencies like OSHA. Although scholars do not typically employ the framework of “social movements” to describe the activism of economic elites—and the men who ran the NAM and the Chamber certainly qualified as elite—business leaders’ strategies frequently mirrored those of their antagonists in the environmental and consumer movements. In addition to developing powerful lobbying infrastructures aimed at the levers of power in Congress and, to a far lesser extent, state legislatures, these business associations also engineered a political “ground game” by mobilizing supporters at local levels. Indeed, they distinguished themselves in the 1970s by forging deep networks among business owners, politicians, policy entrepreneurs, and intellectuals. In revitalizing their position in American politics, they helped create a sense of common purpose among businesspeople and like-minded political allies, a vital characteristic of any social movement. Even when they failed to achieve their stated objectives, such as uniting into one organization or, as we will see, “educating” the public about the virtues of free enterprise, they created a lasting political coalition with profound ramifications in the future.

RISE OF THE OLD GUARD

As the old lions of the American business community, the NAM and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce had seen their influence on policy ebb and flow with the currents of American politics from the Progressive Era through the 1960s. The NAM, the smaller of the two, had the distinction of being older. During the Depression that followed the Panic of 1893, financiers like J. P. Morgan engineered the country’s first corporate merger movement, not only spawning mass concentrations of capital in highly integrated firms but also making industrial policy a paramount concern for businesspeople at all levels. In 1895, more than three hundred industrialists convened in Cincinnati to promote industrial development and the freer trade of American manufactured goods both within the United States and abroad. They aimed to strengthen reciprocal protectionist tariffs and thus limit imports from Europe, which threatened to outcompete American manufacturers under the “tariff for revenue only” policies of the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act of 1894. One of that original meeting’s primary conveners, Ohio governor William McKinley—whose eponymous tariff act of 1890 had been replaced by Wilson-Gorman—saw in the nation’s manufacturing community a chance to shore up his bid for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination. Together with his campaign manager, Marcus Hanna, McKinley believed that an organization of manufacturers would help him woo economic elites in the South who had voted nearly lockstep with the Democratic Party since the Civil War. McKinley and Hanna hoped to shift focus to national economic issues, including trade policy, rather than regional politics. (And indeed, they were modestly successful: McKinley performed far better in the South than any other Republican candidate in the post–Civil War era, nearly carrying Atlanta on his way to national victory in 1896, although the Democrats largely retained their grip on the Solid South, as they would until the 1960s.) The NAM’s devotion to national economic growth and foreign trade helped blur regional lines, and the group became an important political vehicle for the McKinley campaign.6

Given the NAM’s subsequent reputation as an antistatist hard-liner organization, the fact that it emerged from a spirit of cooperation between manufacturers and the federal government appears ironic. Yet in its early years, the association actively supported a vigorous federal government—after all, only Washington could establish and enforce protectionist tariffs. After McKinley’s victory, however, many of the NAM’s high-tariff legislative demands came up short, including the tortuously slow creation of the Department of Commerce (finally established in 1903). Employers began to doubt the benefits of the association, and membership declined. In response, the NAM’s leaders shifted their focus from foreign trade to a more energizing issue: fighting the rising power of labor unions. The “labor question” entailed policies that stretched from laws governing work stoppages to the eight-hour day, thus presenting more concrete issues for manufacturers. Buoyed by its newfound antilaborism, the NAM’s rolls swelled, nearly tripling (to 2,742) between 1902 and 1907, and the group cemented what would become its long-lasting reputation as a hardnosed antagonist to unions. But that strategic switch came at a cost: as the NAM focused increasingly on shop-floor issues, the inroads its founders had crafted with politicians and policymakers atrophied. Within a decade, business-oriented Republicans in Washington complained loudly that while the NAM clearly articulated the anti-union position, no organization projected the overall “voice of business” to policymakers.7

Into that void stepped the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, truly a product of its time. The rapid and unprecedented growth of industrial production at the end of the nineteenth century fundamentally reshaped America, yielding not only massive and vertically integrated corporations but also the fiery politics of trust-busting, populism, and unionism. At the same time, the rise of modern management at those large industrial corporations generated a deluge of economic data and rich policy debates. In 1903, Congress responded to this new chapter in the history of capitalism by creating the Department of Commerce, formalizing the federal government’s interest in the mechanics of industrial society. No sooner had the ink dried than government officials and policymakers began to call for direct input from business owners to help them create policies to nurture and regulate industry. Some sought to work through city and state-run chambers of commerce, which had promoted trade on the local level since the early nineteenth century but had no national organization. By 1910, members of the Taft administration proposed a national Chamber of Commerce that would comprise businesspeople from across industries and regions and operate as a clearinghouse of statistics, perspectives, and analysis that legislators could use to formulate policy.8 Heading into his reelection campaign, which he would lose in a three-way race with Theodore Roosevelt and the ultimate victor, Woodrow Wilson, William Taft believed such an organization could have a political as well as policymaking function. Like his Republican predecessor McKinley, Taft believed that nationalizing business issues would help bring southern businessmen to his side in the campaign. (His strategy failed, and the president lost the South badly on the way to a nationwide electoral wipeout.) In April 1912, hundreds of delegates from state and local business associations accepted Taft’s invitation to convene in Washington, where they officially inaugurated the United States Chamber of Commerce.9

As the administrative operations of the American state and the industrial business community expanded dramatically during the 1910s and 1920, the NAM and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce cemented their positions as ardent defenders of private enterprise. As the self-proclaimed voice of all business, the Chamber acquired a greater national profile than did the NAM, which remained relatively small and narrowly focused. In the 1920s, the NAM’s membership peaked at more than 5,000 owner-operators of mostly small and midsized manufacturing firms (those that did less than $10 million in sales per year—approximately $1.7 billion in current dollars—or employed fewer than 2,000 employees), concentrated in the Northeast and Midwest.10 The Chamber, on the other hand, cast a longer shadow and played an important role in major Progressive Era policy debates, including the creation of the Federal Trade Commission. In historian Robert Wiebe’s words, it quickly became “the most successful national association of the progressive era.”11 By 1929, the Chamber boasted nearly 14,000 individual people and companies on its membership rolls, as well as more than 1,500 state and local organizations from across the country. For the group’s leaders, the involvement of such a diverse constituency clearly demonstrated that “business” had a harmonious set of interests regardless of region or industrial sector. In the 1920s, President Calvin Coolidge, perhaps with some exaggeration, proclaimed that the Chamber “very accurately reflect[ed] … public opinion in general.”12

Despite its sunnier public presence, the Chamber joined the NAM in ardent opposition to government policies that infringed on business prerogatives. Antagonism between business leaders and progressive politicians only escalated during the Great Depression, which discredited the business class in general and fueled public distrust of large corporate interests in particular. The NAM did little to bolster its stock with many Americans when, in the first year of the Depression, its president heartlessly prescribed the harsh medicine of laissez-faire capitalism. If poor Americans “do not … practice the habits of thrift and conservatism, or if they gamble away their savings in the stock market or elsewhere,” he asked, “is our economic system, our government, or industry to blame?”13 Prominent leaders at the Chamber of Commerce, at first, were less strident. Under President Hoover and during the early years of Franklin Roosevelt’s term, liberal businessmen like Gerard Swope of General Electric and retailer Edward Filene (founder of the liberal research group the Twentieth Century Club) preached a brand of corporate liberalism that championed collaboration between business and the state, particularly through the economic planning boards created under the National Recovery Act. That honeymoon proved short-lived, however, and the Chamber broke publicly with Roosevelt in 1934 before joining the NAM in full-throated condemnation of Social Security and the National Labor Relations Act the next year.14 Those hallmarks of the Second New Deal, the two business associations charged, violated the “American way” and reeked of socialism.15 In the years to come, the NAM in particular became a haven for virulently anti–New Deal executives, many of whom also supported the rabidly anti-Roosevelt American Liberty League. At the same time, the group’s membership increasingly skewed toward larger firms, and its obstructionism became legendary, cementing a reputation that would last for generations. Indeed, its leaders openly proclaimed at their national convention that the NAM was “out to end the New Deal,” and its activism—however ineffectual—backed up such intransigence: of the thirty-eight major federal proposals on which the group took a position and which subsequently became law between 1933 and 1941, the NAM opposed thirty-one.16

Of course, neither the NAM nor the Chamber made good on its hopes “to end the New Deal,” whose central elements survived World War II to become embedded in the fabric of American political economy. After the war, both organizations retreated somewhat from their screeching anti-Roosevelt vitriol, but they retained staunchly conservative positions on fiscal policy, welfare, and organized labor. As historian Robert Collins has argued, the business community in general softened its once-rigid take on Keynesian economics, accepting a certain level of deficit spending to boost consumption and business growth.17

While they brokered a modest rapprochement with the New Deal state over Keynesianism and, to a very slight extent, Social Security, the NAM and the Chamber nonetheless proved unwilling to bend on labor issues. The National Labor Relations Act of 1935—the Wagner Act—had changed the world of labor-management relations into which the business associations had been born by empowering the National Labor Relations Board to regulate collective bargaining and ban certain antilabor practices. The New Deal’s support for unionization had also spurred the creation of the CIO, which emerged from and then split with the AFL. Unlike its older counterpart, the CIO appealed primarily to industrial unions and lesser-skilled, often more radical workers, much to the chagrin of business leaders already predisposed to distrust labor. Indeed, the much-publicized presence of communists within the CIO, coupled with popular outrage over the strike wave that industrial unions launched shortly after the end of World War II, galvanized a conservative antilabor pushback that the NAM and the Chamber fully endorsed. As the Cold War rapidly redefined American politics after World War II, red-baiting politicians and their business allies accused the CIO of subversion. They threw fuel on the fire by blaming the 1946 strike wave for the onset of postwar inflation and the dramatic rise in consumer prices. (Both charges were exaggerated: while the CIO certainly counted communists and “sympathizers” among its members, its leadership also included adamant anticommunists like ex-socialist Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers; moreover, rising prices mostly reflected the “catch-up” effect after the government ended wartime price controls, which in fact precipitated the strikes.)18

In 1947, the fiercely antilabor factions within the business community—most vividly on display at the NAM—finally achieved an important policy victory after fifteen years of frustration. During the election of 1946, the Republican Party rode a wave of New Deal fatigue and distaste for labor unrest to win majorities in both houses of Congress. The following June, an antilabor, antiliberal, and anticommunist coalition secured passage of the landmark Taft-Hartley Act, which amended the National Labor Relations Act and became law when Congress overrode President Harry Truman’s veto. Although the new legislative strength of the Republican Party proved critical to the successful veto override, the coalition drew considerable support from conservative Democrats as well. In the House, 106 out of 177 Democrats voted to override Truman, as did 20 out of 42 Democratic senators; the Republicans voted more in lockstep. A bipartisan victory against organized labor, Taft-Hartley barred communists from leadership roles in unions by mandating “loyalty oaths,” prohibited shop-floor supervisors and foremen from joining unions, and banned certain types of labor resistance (such as sympathy strikes and secondary boycotts). Most important for the future of business and labor politics, Taft-Hartley also included a “right-to-work” clause, which amended the Wagner Act to permit state legislatures to ban “union shops”—labor contracts that required workers to join a union before being hired (although they could leave the union thereafter). The right-to-work section of Taft-Hartley ultimately led to a bifurcated labor structure in the United States, in which some (mostly northern and midwestern) states permitted union shops and others granted employers far more power to resist unionization.19

The fruit of a ten-year struggle to roll back labor’s New Deal gains, the debate over Taft-Hartley provoked an energetic lobbying campaign that exposed the important institutional divisions within the postwar business community. Business leaders who identified with the “accommodationist” groups, such as the Committee for Economic Development, which advised policymakers on budgetary issues, largely stayed on the sidelines. The chief executives at the Business Advisory Council mostly supported the bill, but they were hamstrung by their institutional structure and could do no lobbying. The NAM and the U.S. Chamber, on the other hand, threw themselves into the thick of things, pushing their anti-union message not only in the halls of Congress but also on the shop floor itself. The NAM in particular invested heavily in workplace propaganda, producing and distributing flyers and “educational” material designed to persuade workers to oppose dictatorial “union bosses.” Such overt lobbying by business caught labor’s supporters by surprise and provoked fierce concern. CIO president Philip Murray, for example, railed against what he called the NAM’s “national propaganda campaign” as labor leaders of all stripes recognized anew the serious challenge that ultraconservative business activists presented. Indeed, labor’s bruising defeat pushed CIO and AFL officials to mend their fences and paved the way for their formal reaffiliation in 1955.20

Taft-Hartley provided a brief moment of rejuvenation for the old-time business lobbies, but it was far from the complete repudiation of New Deal labor policy that its most ardent proponents at the NAM and the Chamber sought. As labor historians have argued, the law strained but did not break the labor movement, and it actually reinforced the government’s commitment to collective bargaining as the centerpiece of labor-management relations. Just as important, the rabid anti-unionism that the NAM and the Chamber displayed during the lobbying effort severely tapped their political capital, cementing their reputations for right-wing rigidity. By the 1950s, each group saw its status and political clout decline notably, particularly after the conservative wave that produced Republican congressional majorities crested and the Democrats regained control of both houses in 1954 (a hold not relinquished in the Senate until 1980 and in the House until 1994).21

Although both groups saw a drop in their relative power in Washington politics, the NAM took the worst of it. In 1951, publisher and business-oriented conservative Malcolm Forbes editorialized that the NAM took such extreme policy positions against labor that its support of any legislation amounted to a “kiss of death.” Such hostility to all aspects of the liberal state both reflected and shaped the NAM’s membership. By the early 1960s, the group attracted primarily midsized family-run companies—80 percent employed fewer than five hundred people—and its executive leaders hailed from all regions of the country. The group also acquired a reputation for reactionary politics, made worse by the exploits of its board member Robert Welch, a California candy manufacturer who founded the rabidly right-wing, conspiratorial, and isolationist John Birch Society in 1958. Nattering negativism and paranoid racism do not a winning political lobby make. For many Americans, as one trade magazine summarized in the early 1970s, the NAM stood out as “the bad guys.”22

The Chamber of Commerce suffered the taint of right-wing radicalism less than the NAM did, but it nonetheless saw its immediate influence on policy decline. After brief flirtations with corporate liberalism during World War II, the organization settled into a traditionally conservative orientation. It advocated fiscal conservatism (balanced budgets with low taxes) but also reluctantly embraced Keynesianism, especially federal stimulus spending in times of recession. Unlike the firebrands at the NAM, its leaders cultivated a staid and mostly nonconfrontational posture, reflecting in large part their diverse constituency. The organization played only a minor role in the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations and occupied what historian Robert Collins has called “the middle of the new spectrum” of business-oriented politics. In his 1969 dissection of power brokers in Washington, political scientist Lewis Dexter dismissed both the Chamber and the NAM as mostly irrelevant. “It is interest ing to note,” he wrote, “how, in almost every conversation I have ever had in which these are referred to, someone will point out how ineffective [they] are.”23

THE NAM GOES TO WASHINGTON

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, as I argued in the previous chapter, corporate executives and business owners from across the industrial spectrum and in all regions of the United States became increasingly insecure and anxious. The crisis of confidence hit home especially hard at the NAM and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, where leaders who had for decades hailed themselves as defenders of a united business community now confronted a growing sense of voicelessness and cultural isolation. Bemoaning private enterprise’s apparent political impotence, the NAM and the Chamber both worked hard to reinvent themselves by reorganizing their political strategies, expanding their memberships and operations, and forging crucial inroads with other conservative and business-oriented organizations.

The NAM began its turnaround first, largely because its leaders realized earlier how far the group had to go to regain mainstream credibility and cultivate allies within government rather than simply screaming from outside the gates of power. In 1962 the NAM’s first full-time president, Werner P. Gullander, came onboard with a clear mandate to improve the organization’s public image and political effectiveness. Like many mid-century business leaders, Gullander was a product of middle America. The son of a Swedish missionary and pastor, he graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1930 and began a career in accounting at General Electric. He ultimately became executive vice president for finance at General Dynamics, a defense conglomerate and government contractor, before taking the reins at the NAM. During the 1960s, Gullander purged the NAM of its radical, Bircher members and created a leaner but more moderate organization. He also prevailed on those NAM members that retained Washington Representatives to take a more conciliatory approach to lobbying government officials—to helpfully explain business’s positions rather than rant and rave about affronts to free markets. “[W]e must look to other means of influencing legislation,” he told NAM staffers, “by shedding light, not just heat, on the subject.”24

Gullander’s reforms laid the groundwork for a sea change at the NAM after the pragmatic Minnesotan retired in 1972. To replace him, the association hired forty-nine-year-old Edgar Douglas Kenna, who had gained some measure of national fame as a college football star during World War II. Leaving his native Mississippi in 1942 after spending his freshman year at Ole Miss, Doug Kenna transferred to West Point and led Army to an undefeated 1944 season, going All-American in the process. A hard-charging quarterback and halfback (who also captained Army’s tennis team and was named All-American in basketball), the 5’11”, 180-pound standout was West Point’s valedictorian in 1945, served a postwar tour of duty in Germany, and returned to coach at Army before entering the private sector in 1949. There he parlayed his athletic prowess, competitive nature, and leadership skills into business success, rising to management positions in firms across a number of diverse industries. By the time he became NAM’s second full-time president (before Gullander, leaders had served one-year chairmanships while continuing to run their own companies), Kenna had garnered experience in electronics, aerospace, farm equipment, and financial services.25

Gullander had set the wheel of change rolling by trimming the NAM’s membership and adopting a less strident tone; Kenna cast himself as an innovator with structural reform on his mind. The organization he inherited, stripped down to 12,000 member companies, retained its focus on small and midsized firms (83 percent of members employed 500 or fewer workers). Even as the NAM shrank, however, the political world it operated in grew increasingly complex. For Kenna, the rapidly changing dynamics of business-government relations required the old organization to expand its legislative focus beyond its traditional bugaboo—organized labor—and develop sophisticated policy recommendations and legislative action plans on a variety of business issues. The proliferation of liberal reform legislation, most especially OSHA in 1970, raised the political stakes for small manufacturers in particular. In response to the concerns about regulatory capture voiced by public interest activists like Ralph Nader and a growing cohort of like-minded legislators in Congress, many new social regulations tightly proscribed the administrative functions of regulatory agencies, intentionally leaving little discretion to regulators themselves. Even more than in the past, Kenna believed, business’s “affairs ha[d] become interwoven with Government,” and the NAM needed “to be in a position where we can work more closely with Congress, the Executive branch and the Regulatory agencies.”26

Committed to engaging in national policymaking more directly, the NAM moved its headquarters from New York City to Washington, D.C., in 1973. It also created a Government Affairs Division that aimed, Kenna said, to keep NAM staffers “in touch with the rapidly changing scene on the Hill.” That division reported directly to the NAM’s leaders “about the bills which are bottled up, those which are likely to move and unfolding situations which could have special urgency for business.” Kenna’s Washington-based strategy also allowed the organization to coordinate testimony before congressional committees and other government agencies by “executives who have a story to tell about what effect a given proposal would have on their company or industry.” Such a focus reflected the group’s newfound commitment to direct lobbying of both lawmakers and officials at regulatory agencies whose daily decisions affected the NAM’s member companies.27

Within a few years, the NAM’s shift in focus to Washington politics led to structural and organizational changes that heralded the arrival, as the group’s president proclaimed in 1978, of a “New NAM”—a more effective and less abrasive vehicle for “supporting the business viewpoint in the governmental process.” Working from the nation’s capital, NAM staff members found it easier to track bills moving through Congress and to monitor, as one leader explained, “what the priorities are in the Committees on the Hill.” A “situation room” at the Washington headquarters helped NAM staffers determine the status of key legislation—on labor law, consumer protection, price and wage controls, international trade, and a bevy of other issues—and use that information to identify which legislators they should target.28

Although the NAM remained, as it had always been, a national organization principally concerned with federal policy, its leaders recognized that business’s political success depended to a large degree on mobilizing sympathetic politicians, activists, and organizations at the local and state levels as well. “Business,” after all, represented far more than a national interest group. The “New NAM” thus created a Public Affairs Committee to centrally coordinate seven field branches, which in turn organized telephone and mail campaigns to municipal and state elected officials. Mirroring the direct-mail techniques pioneered by conservative Republican activist Richard Viguerie in the 1960s, the NAM created what one leader called “a ‘rifle-shot’ approach to alerting the business community to opportunities for taking effective action on important issues.” In addition to keeping business owners around the country informed about specific happenings in legislative circles, this strategy also served a vital movement-building function: it strengthened network ties between the NAM’s national leaders and its members across the country, the heart of a “grassroots” community.29

THE CHAMBER GETS THE MEMO

While the NAM’s structural reinvigorations stemmed from a strong but illdefined sense that its persistent negativity hampered its cause, reform at the Chamber of Commerce boasted more concrete origins. During the 1970s, the Chamber increased its membership approximately fourfold, dramatically scaled up its direct and indirect lobbying activities, forged lasting ties to other conservative political organizations, and strengthened its networks with local affiliates, trade associations, and individual business owners around the country. Those foundational changes arose in direct response to a somewhat infamous 1971 strategy memorandum written by corporate lawyer Lewis Powell. The son of Virginia farmers, Powell earned a law degree from Washington and Lee University and a master’s degree under the tutelage of Felix Frankfurter at Harvard Law School in 1932. From there, he entered the world of corporate law in Richmond, launching a career that included a stint as the president of the American Bar Association, positions on several corporate boards of directors, and ultimately a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court. In the summer of 1971, Powell received a request from his neighbor and friend Eugene Sydnor, president of a chain of department stores and fellow member of the Richmond social elite. Chairman of the Chamber of Commerce’s Education Committee, Sydnor lamented his organization’s somewhat sleepy political posture, particularly given rising anxiety among conservative business leaders. Knowing that he and Powell saw eye to eye on the real problems that stemmed from the lack of collective political activity by business, Sydnor asked his neighbor to lend his gravitas and pen a strategic analysis—it was a mission statement—of ways the Chamber could respond to the challenges business faced.30

The resulting memorandum, ominously titled “Attack on American Free Enterprise System,” quickly made its way to the Chamber’s top leadership in August 1971. (Powell accepted Richard Nixon’s second offer to join the Supreme Court—the first one had come in 1969—in October of that year; he took his seat on the bench in January 1972.) Powell’s memo summarized the widespread belief that a cultural assault on the values of capitalism lay at the heart of business’s political impotence and the spread of stifling regulatory laws, inflationary spending, productivitysquashing labor laws, and high taxes. Moreover, Powell contended, public distrust of businesspeople translated into a more general skepticism of the capitalist system itself. Only by directly confronting that cultural challenge and actively asserting the benefits of the “free enterprise system,” he argued, could business leaders hope to release their shackles and make a better tomorrow. And although many business groups would have to participate, “no other organizations appear to be as well situated as the Chamber” to lead the charge. As the country’s largest employers’ association, Powell wrote, the Chamber boasted “a strategic position, with a fine reputation and a broad base of support.” Its role, he insisted, was “vital.”31

Although Powell’s memo was an “eyes only” document intended for Sydnor and the higher-ups at the Chamber, Washington Post political reporter Jack Anderson caught wind of it and broke the story a year later, once Powell was firmly ensconced on the Supreme Court. The whiff of corporate cronyism proved too powerful for Anderson, a liberal—and avowedly anti-Nixon—columnist who wrote frequently about corruption in government and business.32 Anderson described the Powell Memorandum in sinister terms, the nefarious attempt by powerful corporate interests to subvert the democratic process, and the document has remained a potent symbol among critics of corporate power on the political left ever since. Indeed, some commentators go so far as to suggest that the memorandum itself prompted a “corporate takeover” of American politics.33

The reality of the Powell Memorandum is much more complicated, however. Conceptually the document broke little new ground; business leaders had been voicing many of the same concerns for years, if not as eloquently or persuasively. Thus rather than a clarion call for a counter-mobilization by conservative businesspeople, the Powell Memorandum is better understood as a tool for institution building. As legal scholar Steven Teles has argued, the memorandum called specific attention to the hegemony of legal liberalism in the judicial system, to which conservative lawyers and politicians later provided intellectual counterpoint by modifying law school curricula and creating national organizations like the Federalist Society. Quickly spreading beyond the Chamber of Commerce, the memorandum achieved a wide readership within conservative political circles and its main arguments—often quoted verbatim—became important talking points in the halls of think tanks, policy meetings, fund-raisers, and conferences.34

More important, the memorandum left a profound legacy at its specific institutional target. Eugene Sydnor, one director among many at the Chamber of Commerce, circulated the document widely, making sure it hit the desk of the group’s chief decision makers. Perhaps nothing reflected so clearly the bureaucratic culture that dominated the creaky Chamber of Commerce than its leaders’ initial response to Powell’s rousing call for action: they formed a committee. Early in 1972, the Chamber’s Committee to Interpret Business met for the first time and committed itself to “interpreting”—that is, translating—the benefits of free enterprise for nonbusinesspeople. For the Committee to Interpret Business, “selling the American way to the American people” had to become “the No. 1 priority for the nation and the business community,” and the Chamber thus created a special task force on the Powell Memo to deliver specific recommendations.35

While it awaited the task force’s results, the Chamber’s board of directors responded to Powell’s suggestion that the Chamber become the national leader of a broad-based business movement by retooling the group’s leadership structure. Since 1912, the Chamber’s chief officer had been its president, a business owner or chief executive, often with a national reputation, who served as the group’s spokesman for a year but didn’t quit his day job. To create greater strategic and organizational coherence at the highest level, the Chamber created a permanent presidency in 1974 and renamed the yearly position as chairman of the board of directors. Mirroring the process at the NAM through which Werner Gullander became the full-time leader, the Chamber elevated longtime executive vice president Arch Booth to be its first president.36

The task force on the Powell Memo reported back in 1973 with a set of specific policy recommendations. The first was to resume contributions to the Business-Industry Political Action Committee (BIPAC), which had lapsed since the 1960s. The Chamber’s board voted to donate $25,000 to BIPAC’s Political Education Division, which promoted issue items and provided information about the political process—such as how to lobby, vote, or raise funds for candidates—but did not directly contribute to political campaigns. By limiting its contributions to BIPAC’s “educational” function, the Chamber hoped to remain above the fray of electoral politics and thus retain its influence with as wide a range of policymakers as possible.37

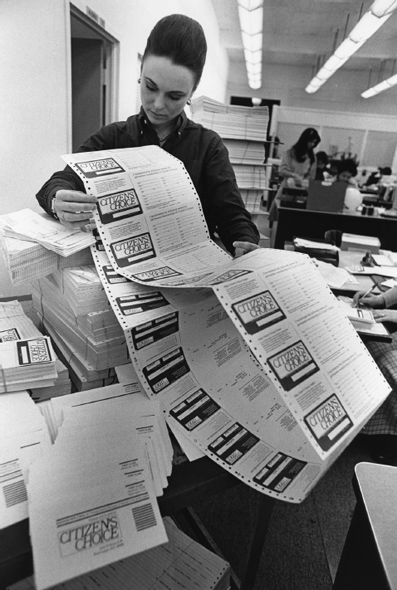

The Chamber also dramatically expanded its organizational structure by creating several affiliated groups. These included a think tank called the National Chamber Foundation, whose purpose vice president Thomas Donohue explained as “conducting and publishing research on public policy issues of critical importance to the stability of the enterprise system.” Another new organization, Citizen’s Choice, worked to generate political enthusiasm among a network of tens of thousands of “rank and file workers, professionals and retirees” by sending them “a monthly newsletter, special action alerts on important legislation, [and] access to a tollfree telephone hotline number providing weekly updates on pending legislation.” Calling itself a “grassroots” organization, Citizen’s Choice played a vital role in the Chamber’s indirect lobbying: as national leaders pinpointed specific legislators whom they wished to persuade on any given vote, they could tap into a vast network of “regular people” to bombard their representatives with constituent mail. Finally, perhaps the most influential new affiliated organization, the National Chamber Litigation Center (NCLC), emerged in direct response to Powell’s concerns about the judicial system’s hostility to business. While Citizen’s Choice promoted indirect lobbying through grassroots mobilization, the NCLC represented a different approach—direct legal challenges to regulatory enforcement. Beginning in 1977, the group pooled corporate resources to defend individual companies that faced legal actions regarding workplace safety, equal opportunity, or antitrust laws.38

The flurry of activity that overtook the formerly lackluster Chamber of Commerce in the aftermath of the Powell Memorandum climaxed with the arrival of an entrepreneurial new leader, Dr. Richard Lesher, in 1975. A former business school professor with a Ph.D. in business administration, Lesher had previously worked as an administrator for NASA and had forged his bona fides within the manufacturing community as president of the National Center for Resource Recovery. As head of that industryfunded research organization dedicated to extracting usable materials (copper, iron, even natural gas) from industrial waste, Lesher had worked to improve recycling technology and promoted its virtues to businesses by stressing the cost savings it entailed. When sixty-eight-year-old Arch Booth announced his retirement from the Chamber in 1975, the board of directors looked to Richard Lesher to assume the helm.39

Booth was a Kansas native who began his career on the staff of the U.S. Chamber in 1943 after running the Wichita chamber of commerce and became executive vice president in 1950 at the age of forty-three. Although he held the title of “president” only for the last year of his tenure, he had been the group’s highest-ranking permanent leader for most of those twenty-five years and thus left an indelible stamp on the organization’s culture. According to Chamber senior vice president Carl Grant, Booth was a “tight-fisted” manager who maintained strict personal control over day-today operations, perpetuating a traditional and conservative aura throughout the association. He penned a weekly syndicated business column called “The Voice of Business,” which appeared in local and national newspapers across the country, oversaw the publication of the Chamber’s monthly in-house journal, Nation’s Business, and appeared as a guest speaker on a low-profile radio program that the Chamber ran.40

Figure 2.1. In this undated photo, a staff member at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce prepares a mass mailing for Citizen’s Choice, a “grassroots organization” the Chamber created to lay the groundwork for indirect lobbying through a massive network of informed and energized local business owners and professionals. Courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library.

For Richard Lesher, only forty-one years old when he replaced Booth, such public outreach represented an important but incomplete part of the Chamber’s grand strategy. A careful student of the Powell Memorandum, Lesher believed that the Chamber could only achieve the public visibility it needed by creating a technologically sophisticated media operation through which it would serve the business community as both a communications hub and a policy house. In the late 1970s, Lesher thus oversaw the creation of a satellite television network that linked local and state chambers of commerce and offered specialized programming and videoconferencing. The main component of that American Business Network was a weekly half-hour debate program called It’s Your Business, which Lesher moderated. After 1982, the Chamber broadcast the show directly from a state-of-theart studio in its headquarters in Washington, D.C. (across Lafayette Square from the White House). As cable television spread across the country in the 1980s, the Chamber went with it. Its two-hour morning business news program, Nation’s Business Today, began airing on ESPN in 1985. Although Lesher’s gung-ho approach to new media raised the Chamber’s public visibility, some conservative holdouts at the staid institution bristled at his public presence, claiming in particular that the debate show It’s Your Business amounted to self-promotion. Nonetheless, the results proved undeniable: under Lesher’s leadership, the U.S. Chamber rose from the ashes in a few short years to become a major voice in the politics of business.41

Richard Lesher’s public communications revival at the Chamber helped fuel tremendous growth. In addition to taking on new permanent staff members and vice presidents hired to run the multimedia communications network, Lesher also expanded the group’s sales force and aggressively courted new member companies, local chambers, and trade associations. As a result, the Chamber’s membership rose from 50,000 in 1970 to more than 200,000 by the early 1980s. Indeed, the membership boom and the communications blitz reinforced each other. The benefits of membership, sales representatives told potential recruits, included a subscription to Nation’s Business; that growth in readership increased the magazine’s advertising base, generating new revenue that it used to augment the quality and relevance of its reporting.42

Lesher’s organizational and spiritual revivalism at the Chamber of Commerce in many ways reflected the broader trajectory of conservative activism in the United States in the 1970s. Like many other conservative organizations, the Chamber deployed modern and sophisticated methods, such as television, radio, and computer-generated direct mail solicitations, in the service of increasingly traditionalist, strident, and confrontational politics. Young leaders like Lesher vocally rejected the alleged postwar “consensus” by which prominent business leaders made peace with New Deal liberalism, from Keynesianism to public interest regulations. Instead he helped bring the conservative critique more fully into the mainstream of national politics during the 1970s, joining in a larger project that built on longstanding antistatist ideas and unapologetically advocated for unfettered enterprise. Responding to the rise of new social regulations that limited regulators’ discretion and encouraged inflexible “command-and-control” rule making, the new Chamber president delivered a vitriolic stump speech around the country in 1975 and 1976 provocatively asking: “Can Capitalism Survive?” “Did you know,” Lesher railed, “that Agents of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration can raid a place of business any time they want … [and that] the Environmental Protection Agency has the power to destroy a city?”43

Lesher’s ideological fervor bolstered the Chamber’s image as a conservative crusader for business interests but contrasted sharply with the generally more conciliatory approach that dominated large national business associations like the Business Council and the Committee for Economic Development, which were run by executives and business owners themselves, rather than political activists. Nowhere did this tension appear clearer than in the series of debates over “corporate social responsibility” that unfolded within business circles in the 1970s. Amid plummeting public approval ratings, only exacerbated when the Watergate scandal revealed deep patterns of corporate corruption, business leaders turned introspective, asking what they had to do to convince Americans that they performed a positive social function. John Harper, CEO of aluminum giant Alcoa, had laid out the major features of the social responsibility debate as early as 1967 in an article for the Public Relations Journal. Bristling against stricter environmental and consumer safety regulations, many corporate leaders called for massive resistance to the government’s assault on their autonomy. Blazing a middle ground, Harper contended that the American people had a legitimate right to worry about things like pollution, product safety, and workplace health, but business leaders could respect those complaints without surrendering operational control to heavy-handed regulatory authorities. Indeed, business leaders could “prevent further regulation best by anticipating needs and meeting them voluntarily.” In essence, Harper’s article repeated a longstanding argument, articulated as early as the Progressive Era, that far-sighted actions by business leaders could provide a hedge against governmental overreach. Even as an increasingly distrustful public called ever louder for legislative remedies, most business leaders clung to Harper’s optimistic prescription.44

For Richard Lesher, on the other hand, Harper and businessmen like him preached nothing short of appeasement. In a fiery editorial in the summer of 1976, Lesher loudly denounced the persistence of public debates over the “long list of things business is or ought to be involved with,” including “health care, the environment, product safety, [and] equal employment opportunity.” Such wrangling, Lesher declared, missed the broader point. Americans should not debate business’s social responsibility, he claimed, when “the one MAJOR social good that business performs isn’t even on the list: IT CREATES JOBS.” In a country facing a severe recession (official unemployment was 8 percent in 1976 and GDP growth had flatlined since 1973), Lesher insisted that business’s social function was its economic function. “Next time you’re discussing the ‘social good’ business does, point out that it does PLENTY…. But the number ONE good is: IT CREATES JOBS.”45

By dismissing the very notion of corporate social responsibility, Lesher clearly articulated the key strategic differences between the Chamber of Commerce and big-business organizations. In fact, Lesher’s argument mir rored very closely the claims long espoused by Milton Friedman, the University of Chicago economist and chief proponent of the monetarist critique of Keynesianism. For years, Friedman had worked to rehabilitate neoclassical economic thinking in intellectual circles, arguing that the government obstructed the liberating operations of the market by distorting incentives and that, in a philosophical sense, the greater good would arise through the free exercise of enlightened self-interest. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Friedman’s star rose dramatically, aided by a faltering economy, growing distrust in the prescriptions of Keynesian demand management, and, in no small part, the network of conservative activism to which Richard Lesher hitched his wagon at the Chamber.46

In a famous article in the New York Times in 1970, Friedman inveighed against the very notion of “corporate social responsibility.” From an economic perspective, he claimed, corporations were artificial entities that only existed to pursue profit. Since “[o]nly people can have responsibilities,” the whole premise of the debate was flawed. (According to this argument, a corporation that failed to make a profit would soon cease to exist, all other things being equal, so its only true function must be profits.) Friedman thus distinguished between corporations (a legal creation) and the human beings who ran them (who could logically be said to have social responsibilities). Lesher, on the other hand, invoked far less nuance and took a more overtly political stance, arguing that neither businesses nor businesspeople owed anything to society except economic growth, and any efforts to control corporate autonomy necessarily compromised prosperity. As the Chamber of Commerce expanded its structure, media presence, and lobbying under Richard Lesher’s leadership, its commitment to its founding principles and its antagonistic posture toward the liberal state crystallized.47

SELLING THE MARKET

The drive for renewal, revival, and restructuring that swept the old-time Chamber of Commerce and the NAM in the early 1970s emerged from the palpable panic among corporate leaders. In all corners of the business community, executives and small business owners, as well as their paid representatives at trade and employers’ associations, decried their cultural isolation and voicelessness in the wake of rising foreign competition, declining profit margins, and heightened regulatory responsibilities. Public hostility to business appeared to be growing, especially among what Lewis Powell called “perfectly respectable elements of society”—schoolteachers, ministers, college professors, and journalists.48 “Americans do not understand their own economic and business systems,” declared the Chamber of Commerce’s newsletter. As a result, according to another executive: “Every day in a piecemeal way, the public unwittingly destroys the free market.” Business, it appeared, simply could not get its message across.49

Corporate leaders’ fixation on that problem prompted an explosion of efforts to recast Americans’ understanding of business and economics and to rehabilitate the public image of corporations as well as the men (and sometimes, rarely, women) who ran them. Collectively called “economic education,” such programs targeted primary and secondary schools, universities, the media, and the public at large. “Economic education,” the NAM’s Public Affairs Committee proclaimed, was dedicated to the proposition “that society’s ills can be overcome through the workings of the free enterprise system.” For leaders at major employers’ associations, this project became an all-consuming passion in the mid-1970s.50

Of course, the idea of “educating” the public about the virtues of business and capitalism far predated the 1970s. From their inception, the NAM and the Chamber had dedicated great resources to “teaching” the public about the glories of the free enterprise system and the perils of socialism (a term wantonly waved around, whether it fit the situation or not). In the 1920s and 1930s, the NAM helped member firms organize “company unions” and then bombarded factory workers with “informative” brochures and fliers to build support for those in-house boards that undermined independent unionization efforts. During the legislative fight over the Taft-Hartley Act in 1946 and 1947, the NAM developed a shop-floor strategy, providing workers—a captive audience—with information about the threats posed by communists in the labor movement and the virtues of the “right to work.” Moreover, in 1945, a former Chamber of Commerce director named Leonard Read created the Foundation for Economic Education, the country’s first libertarian think tank, which published uncountable brochures and pamphlets, even record albums, preaching the laissez-faire gospel. While the Chamber itself focused more on concrete policy than abstract philosophy, it, too, published and distributed educational material, producing booklets with titles like “The American Competitive Enterprise Economy,” “Understanding Economics,” and “Freedom v. Communism.” Indeed, throughout the postwar period, business leaders beat the drum of public education unceasingly.51

But the drive for economic education in the 1970s unfolded amid a different public climate. In many circles, economic libertarianism was on the march through think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute, the beneficiaries of massive grants of private capital, which produced thoughtful and politically viable policy recommendations to actively roll back New Deal–era labor laws and new social regulations. By the end of the decade, Milton Friedman would produce a popular television documentary, Free to Choose, expounding on the benefits of capitalism and free markets. New organizations also flourished on college campuses, including Students in Free Enterprise, which by the late 1980s sent people wearing giant pencil costumes to junior high class-rooms to carry the pro-capitalist message to preteens. (Friedman, in Free to Choose, had riffed on Adam Smith’s famous description of pin production by explaining that no individual person could actually make a graphite pencil; only the profit motive could bring it into existence.) In the long run, the stakes of this intellectual movement were enormous. Free-market fundamentalism argued that “the state” and “the market” existed in separate and antagonistic spheres and that the market became increasingly “free” as state power declined. Such a vision explicitly denied the notion that states, through their legal and administrative functions, in fact constituted markets. Thus, rather than mediate the claims of competing interests on the market, economic libertarians claimed that policymakers should unilaterally eliminate state activity and allow market forces to govern society. To be sure, such extreme neoliberalism rarely manifested in a pure form in any serious policy debates, but by the 1980s and 1990s it would significantly permeate national discourse and place major limitations on policy options.52

The debates over economic philosophy that entrepreneurial activists like Richard Lesher engaged in during the 1970s thus fit snugly into a longer intellectual project. Moreover, during the early 1970s, economic education projects also provided a tremendous opportunity for the crusty old business lobbies to expand their influence. Renewed attention to such programs permitted the NAM and the Chamber to develop new physical infrastructure and vital networks, both within the business community and between corporate leaders and other conservative activists. The NAM’s Public Affairs Committee, created in 1975 as part of the group’s organizational revival, ran workshops that provided businesspeople with stock speeches and audiovisual aids, encouraging them “to seek out speaking engagements on college campuses and before educator audiences and student groups at all levels.” The NAM also created an Organization Services Department in 1975 to establish relationships with local business groups and community organizations such as the American Legion, to which it mailed “packaged programs” on various business issues.53

Public outreach efforts targeted both specific legislation and general business topics, especially the question of profits. In the aftermath of the oil embargo by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in late 1973, inflation quickly became the nation’s number one economic problem, and many consumers blamed corporate fat cats for price gouging. Prominent liberals in Washington—and many campaigning for Congress, including a young Arkansan lawyer named William Clinton—demanded a “windfall profits tax,” similar to provisions imposed during the two world wars to prevent profiteering. In 1973, the Chamber of Commerce produced and sold a “Profits Kit” that included charts, articles, and “suggestions on how to use the materials to get the story out—to employees in your plant or office, to customers, to your community through newspaper ads, radio spots, posters, stickers, buttons, and reprints.” Written by the group’s in-house economist, Carl Madden, the kit proudly declared that “Profit is not a 4-Letter word!”54

In their campaigns for economic “literacy,” business leaders targeted the medium as well as the message. As I argued in chapter 1, complaints that the national media suffered a “liberal bias,” while certainly nothing new, grew louder and more pitched in the early 1970s. From Walter Cronkite’s famous denunciation of the Vietnam War effort to Woodward and Bernstein’s exposé of Watergate (and to a far lesser extent, their colleague Jack Anderson’s “outing” of the Powell Memorandum), journalists achieved infamy in conservative circles. “It makes me sick to watch the evening news night after night and see my husband and the efforts of his industry maligned,” the wife of one executive complained in 1975.55

For the NAM and the Chamber, media relations constituted a vital part of their “education” strategies. The NAM’s first reformist president, Werner Gullander, instituted what he called a “press-panel ‘sales’ approach” with journalists, inviting them to sit onstage with him during his public appearances and creating an informal media roundtable. In 1975, the NAM’s Public Relations Committee launched a series of public seminars to forge contacts between business leaders and writers and editors, particularly from business and financial news outlets. As president, Doug Kenna used his personal connections with television network executives to improve communication and understanding between executives and journalists—businesspeople would acknowledge the importance of helping journalists meet deadlines and agree to provide truthful, verifiable statistics for business articles; in return, journalists would try to address businesspeople’s complaints about biased coverage.56

While businesspeople loved to whine about the media, many also believed that Americans’ ignorance of business developed long before they became consumers of the news. Changing hearts and minds thus required catching them while they were young and impressionable, in the nation’s schools. But schoolteachers, a Chamber researcher reported, “seem[ed] to be ignorant of the business world and economics.” Indeed, according to one poll, “the majority of high school teachers and students thought a high standard of living comes by limiting profits.” In the mid-1970s, the Chamber of Commerce used its publishing infrastructure and distribution networks to produce and sell an elaborate educational program for high school students called “Freedom 2000.” The materials included a teacher’s manual, comprehension and discussion questions, and an animated motion picture. In the movie, aliens visited Earth to learn why some societies were wealthier than others. Spoiler alert: the reason was “an economic system in which the rights and choices of the individual are of paramount importance.” That message directly reinforced many business leaders’ central argument against aggressive consumer and environmental protection legislation by subtly suggesting that caveat emptor and selfmonitoring by business were preferable to command-and-control regulations.57

Although businesspeople often bemoaned the poor content of high school economics education (which they claimed ignored such concepts as the profit motive, the intersection of supply and demand, and the division of labor), programs like “Freedom 2000” and a similar one from the NAM called “Remember the Future” generally avoided specific issues and aimed instead for a more visceral reaction, hoping to boost students’ appreciation of the free enterprise system and of corporations. Other outreach programs likewise worked to build personal connections across political and generational lines, including the Chamber’s College-Business Symposia. Launched in the late 1960s amid antiwar and anti-establishment campus activism, these events were coordinated by the national office but sponsored by local chambers of commerce and trade organizations, bringing what one participant called “the gray-flannel group” into contact with the “bushy hair and sideburns” crowd. Business groups also sponsored seminars and summer camps for high school and college students that included business simulation activities that allowed participants to make decisions about marketing, financing, and even labor relations.58

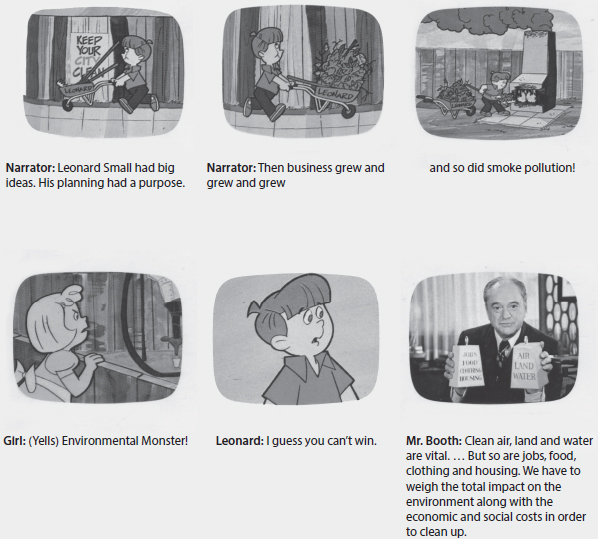

Figure 2.2. This animated public service announcement, produced for the Chamber of Commerce by Hanna-Barbera studios in 1973, explained the Chamber’s position on striking a “balance” between fighting pollution and promoting economic growth. Courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library.

A final forum for economic education that saw a burst of activity in the early 1970s concerned print, television, and radio advertising. Although the NAM, the Chamber of Commerce, policy institutes, and corporations had “advertised the American Dream” since the rise of mass consumer advertising in the early twentieth century, the rapid spread of television and the urgency of the moment led pro-business activists to invest substantial sums of money in increasingly elaborate campaigns. In 1972, the Chamber of Commerce’s Education Committee (chaired by Eugene Sydnor, procurer of the Powell Memorandum) hired Hanna-Barbera Studios, famous for their primetime family shows The Flintstones and The Jetsons, to create a series of animated public service announcements (PSAs). The disarmingly playful thirty- to sixty-second cartoons broached complex economic problems, including foreign trade, pollution, and product safety, in simplified tones. They then cut to the live-action grandfatherly visage of Arch Booth, who explained how “free markets” offered the cure to any problem. In the case of pollution, as figure 2.2 shows, Booth calmly explained the necessity of trade-offs: “Clean air, land and water are vital to all of us,” he said. “But so are jobs, food, clothing and housing. We have to weigh the total impact on the environment along with the economic and social costs in order to clean up.” Like the packaged programs for high school and college students, such advertisements trafficked in platitudes and generalities, framing business debates in terms of personal freedom, economic opportunity, and the perils of socialism. Although spurred by complaints that the public suffered from an unsophisticated understanding of economics and business, most economic education programs in fact provided little more than philosophical propaganda.59

THE LIMITATIONS OF ECONOMIC EDUCATION

During the go-go period of institution building and ideological fervor in the early to mid-1970s, economic education programs were all the rage among business elites. Longstanding associations like the NAM and the Chamber, as well as the Foundation for Economic Education, expanded their earlier initiatives, and new organizations joined the fray. But did their efforts pay off? Although the quantity and breadth of economic education material clearly rose, one might well question its effectiveness. It simply strains credulity to suggest that any individual person saw a billboard, ate pancakes over a placemat touting free enterprise, or read a magazine advertisement and then fundamentally revised her political beliefs. Yet by bombarding the public with fervent praise of private enterprise and unflinching condemnation of organized labor and government bureaucracy, the campaigns may well have shaped the zeitgeist, however difficult it might be to measure their precise effect.

By the standards that business leaders set for themselves, however, the public education push did not meet its primary goal of raising Americans’ opinion of business. Millions of dollars and years of speeches, packaged programs, textbooks, brochures, and ad buys did not move the needle on public confidence in business at all. The number of Americans who claimed to have “a great deal” of confidence in the leaders of major corporations (the closest proxy in the surveys to “business” as a social institution) declined from 50 percent in the 1960s to 20 percent by the mid-1970s and never rebounded. Even during the “Reagan recovery” of the mid-1980s and the roaring 1990s, rarely did more than 30 percent of Americans proclaim “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in corporate leaders. (The most common amount of confidence was “some” and that figure hardly changed from the 1970s to the present.)60

In time, association leaders, corporate executives, and even think-tank activists and journalists acknowledged this failure and began a strategic retreat from their best-laid plans. In 1977, NAM president (and former U.S. Steel executive) Heath Larry opined that “so many countless efforts to overcome ‘economic illiteracy’ have been funded by industry that it’s almost scandalous.” Thus while employers’ associations never fully abandoned public outreach as a strategy, they increasingly dedicated themselves to hot-button legislative issues, mobilizing grassroots lobbying campaigns and directly pressuring policymakers. Even the Chamber’s vaunted television programming, which continued until Lesher stepped down as president in 1997, typically dealt with specific policy matters rather than a broad-based campaign to revive faith in business or capitalism itself.61

The campaigns for economic education failed—at least on their own terms—because corporate leaders and the heads of business associations fundamentally misinterpreted the public’s mind-set and critique. In truth, there never was a broad-based “attack on the free enterprise system.” Faith in free-market capitalism ran deep in the nation’s political tradition, and historically, socialistic alternatives to a free enterprise economy garnered very little support. The dominant question in the history of American political economy has never been “capitalism or socialism?” but “what type of capitalism?” According to a survey taken in the summer of 1971, exactly as Lewis Powell penned his memorandum, 66 percent of Americans agreed that the “free enterprise system” provided the best path to a higher standard of living, while only 20 percent thought “government help” was the best route. In 1978, a poll conducted for the business-friendly U.S. News and World Report concluded that the “public’s concern is with business per se, not with the system within which it operates,” a view supported by many other national surveys.62

Moreover, no evidence suggests that Americans’ aggregate understanding of economics was any lower in the mid-1970s than it had been in the mid-1960s, when business enjoyed very high approval ratings. At least one member of the NAM’s Education Committee had cautioned as much in 1973, telling fellow members that “[e]conomic literacy and the anti-business bias prevalent today are not the same problem.”63 More likely, to the extent that public outreach efforts changed the nation’s political conversation, they did so by “educating” Americans about the (allegedly pernicious) effects of regulations and unions on economic prosperity, not by rehabilitating the image of business itself. For example, between the mid-1960s and the early 1980s, the percentage of Americans who believed that government went “too far” in regulating business increased from 40 percent to 65 percent, and those numbers have remained as high ever since, even during the Great Recession that began in 2007. The degree to which such a shift in public sentiment reflected propaganda campaigns by business, as opposed to general antigovernment sentiment and the absolute growth of the regulatory state, is impossible to measure, but that shift certainly did not bring with it greater public confidence in business leaders.64

Public confidence in business leaders simply moved on a different scale than either faith in free enterprise or formal understanding of business and economics, but many business leaders were slow to come to grips with that fact. Their reluctance is perhaps understandable if we consider their mind-set—if you believed in and understood the system, they felt, it only followed that you would have faith in the men who ran it to the best of their ability. But the American public did not think that way, especially in the 1970s. Public cynicism toward business emerged as part of a broader set of cultural trends, born of dislocation and malaise and fueled by economic doldrums, foreign policy failings, and political scandals. Americans’ faith in all social institutions—the military, the government, labor, even religion—declined during this period, and in most cases public confidence never recovered the high levels of the 1950s and 1960s.65

And yet in an important sense, the economic education programs did not fail but in fact formed an integral part of a major political mobilization. On the most straightforward level, these programs reaffirmed and solidified fundamental philosophical commitments to the primacy of markets and demonstrated to conservative politicians that corporate leaders could be staunch allies in what activists framed as a culture war against the excesses of New Deal liberalism. Just as important, the economic education programs helped reenergize the sleepy old business lobbies. Initiatives like the Hanna-Barbera PSAs and the media blitzes by the NAM’s Public Affairs Committee convinced members that these groups stood ready to take the fight directly to antibusiness elements in government, academia, and the press. Indeed, the very process of funding, creating, and distributing economic education packages, programs, television and radio spots, and print ads required leaders of the national organizations to strengthen ties with their tens of thousands of members. Public relations campaigns naturally have multiple audiences, and in this case, unifying the internal audience yielded a more important legacy than persuading the external audience. Strengthened networks within business associations proved invaluable to later lobbying, as these public relations campaigns generated a common identity that helped business groups overcome collective action problems and speak increasingly with a single voice.

OLD LOBBIES IN A NEW AGE

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers reinvented themselves in the late 1960s and early 1970s in direct response to the acute challenges business leaders believed they confronted. As powerful mouthpieces for a business-oriented approach to solving economic policy problems, these two organizations formed part of a far larger movement of libertarian and economically conservative political actors that revolutionized both lobbying and politics. Indeed, the aggressive and often hyperbolic fear-mongering of men like Richard Lesher helped strengthen strategic and ideological ties between business associations and a burgeoning conservative intellectual movement. Born of the same antiregulatory, antilabor spirit that animated the NAM and the Chamber, conservative and libertarian think tanks invoked fevered Cold War rhetoric to condemn liberalism, warning that America could easily follow England and France down the slippery path first to socialism and then to Soviet-style communism. Conservative pundits, politicians, and intellectuals read and quoted extensively from the Powell Memorandum and helped popularize the notion that public interest regulations, labor unions, and even affirmative action and civil rights represented a blatant attack on “free enterprise” and a deep threat to America’s economic health.66