A Tale of Two Tax Cuts

Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.

— John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936)

BY THE END OF THE 1970s, the Chamber of Commerce of the United States had much to brag about. “Business people are increasingly recognizing the need for both legislative and political action at the grass roots—and improving their effectiveness at both,” the group crowed in 1980. For example, despite predictions that the Congress elected in the fall of 1974, right after Watergate, would be “overwhelmingly liberal and anti-business,” the Chamber declared victory on two-thirds of the 71 policy issues it tackled in 1975 and 1976. The 95th Congress elected along with Jimmy Carter in 1976, it continued, “brought no better outlook for the business sector,” but “business people had now proved to themselves and others what they could do.” Out of 107 issues, the Chamber claimed a win on 65 percent and a loss on only 12 percent. (The rest were split decisions.) Finally, by 1978, the group boasted that businesspeople had finally learned to couple “grassroots” lobbying with a major effort “to elect leaders who will further advance the nation’s economic interests.” In that year’s midterm election, the group’s political action committee, the National Chamber Alliance for Politics, identified 83 races where it found “a clear philosophical difference between the candidates and where business participation [could] make the difference.” Fifty of its candidates won, helping the Republican Party chip away at Democratic majorities by gaining fifteen seats in the House and three in the Senate. Looking ahead to the 1980 elections, the country’s largest business association saw a great opportunity to begin “the task of getting our economic house back in order.”1

Yet the Chamber’s leaders also saw significant challenges ahead. “The economy is currently moving into a worse-than-average recession, and the recovery, when it occurs, is likely to be shallow,” reported the group’s chief economist in June 1980.2 Indeed, the economic turmoil the United States confronted dwarfed any problems of the previous forty years. The short-term statistics were dizzying enough. Inflation again hit double digits, propelled by a second oil crisis in the wake of the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Crude petroleum prices shot up 150 percent and the nominal average price of gasoline in the United States topped one dollar per gallon for the first time ever. Making matters worse, economic growth ground to a halt after newly installed Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker launched a radical three-year experiment with monetarism in the fall of 1979. By directly limiting the growth of the money supply, Volcker pushed the country into its third official recession in eleven years. Gross domestic product contracted by a record 9.9 percent in the second quarter of 1980, and interest rates fluctuated with maddening volatility. But the cyclical downturn and inflationary crisis marked only the tip of the iceberg. Long-term shifts in global industrial production underlay those difficulties, hastening the decline of U.S. manufacturing and adding new urgency to business leaders’ calls for action. During the 1980s, these new economic dynamics would permanently redefine the contours of American capitalism and profoundly shape the organized business community.3

As the economic crisis unfolded, the political world turned its attention to the quadrennial tradition of the presidential election as Jimmy Carter fought for survival against former California governor Ronald Reagan. Adhering to their longstanding practices, the Chamber, the NAM, the Business Roundtable, and most other business associations remained officially neutral during the campaign. Nonetheless, when Reagan won a landslide electoral victory with slightly more than 50 percent of the popular vote, the men who had spent their careers clamoring for business-oriented fiscal policies appreciated the importance of the Republican triumph. To be sure, Jimmy Carter was a far cry from the labor-coddling, heavy-handed regulator that many conservatives feared he might be, and corporate lobbyists had achieved great success pulling him away from his more liberal advisors. All the same, Reagan’s victory symbolized a powerful rebuke to much of the rhetoric and promise of modern liberalism, and most business leaders welcomed the arrival of an avowed conservative who preached an antistatist, antiregulatory gospel.

But the political ascent of conservative Republicans ultimately proved a mixed blessing for organized business leaders. Despite the new tenor of national politics, business conservatives soon found that the task of actually implementing their policy agenda amid the pluralistic contentiousness of the American political system was fraught with difficulty. As self-described political outsiders in the 1960s and 1970s, corporate leaders had united around vague yet passionate calls for “pro-business” policies—a hard line against labor power, tight fiscal policy, and opposition to price controls, social regulation, and national planning. Once conservatives took the reins of power, however, those ideological issues devolved into complex and often divisive policy debates. As this chapter argues, nowhere did those tensions flare more brightly than in conflicts over macroeconomic policy, especially over taxes.

The interlocking problems of taxation and the federal budget set the stage for the contentious politics of business in the 1980s. During the Reagan administration, ideological small-government conservatives clashed openly with the heads of manufacturing and other traditional capital-intensive business firms. In spite of their superficial common opposition to Keynesian demand stimulus and organized labor, these disparate groups of conservatives held sharply divergent priorities. Their struggle produced a tale of two tax cuts. One, supported by industrialists, aimed to revitalize manufacturing by providing incentives for investment and savings. The other, an antistatist quest to lower all taxes, garnered greater populist appeal. Although not mutually exclusive—both found a way into Reagan’s tax reduction legislation in the summer of 1981—these competing visions marked an emerging schism within the ranks of conservatism. Although Ronald Reagan has achieved a lasting place in conservative lore as a foe of big government, a champion of entrepreneurs, and a tax-cutter nonpareil in American political history, his fiscal policies in fact engendered substantial conflict among conservative organizations, most notably the organized business lobby.

THE CAPITAL ACCUMULATION MOVEMENT

As business leaders, particularly industrial executives, mobilized politically in the 1970s, they rallied around the belief that liberal federal policies depressed profits and productivity by distorting managerial decisions and imposing undue costs. In earlier decades, as the Business Roundtable’s newsletter explained in 1980, “new capital invested by business was spent entirely to finance growth.” But during the 1970s, “with business responding to public concerns other than increased production, some of the new capital is channeled into other areas—providing safer, healthier working conditions, for instance, and protecting the environment.” Every penny corporations had to spend to comply with social regulations, to pay the inflated price for supplies, to compensate a worker in excess of that worker’s productivity, or to fund the federal government through corporate income taxes, business leaders argued, represented money they could not spend to improve their operating capacity and hone their competitiveness. The result was a dearth of capital investment in productive facilities. “To recover growth in productivity,” a Chamber of Commerce brochure claimed, “requires a higher rate of personal savings and increased investments in modern and efficient equipment and technology.”4

As profits continued to stagnate and productivity growth remained low, industrial leaders demanded a policy response. Among the most vocal advocates was Reginald Jones, successor to Fred Borch as chief executive officer at General Electric in 1972, who assumed his predecessor’s role as a dominant force at the Business Roundtable and chaired the group’s Taxation Task Force. The son of a steel mill foreman, Jones emigrated with his family from England to New Jersey as a boy yet retained his British accent and affected certain stylistic trappings that, according to his contemporaries, gave off a patrician air. After matriculating at the University of Pennsylvania with the hope of becoming a teacher in 1930, Jones transferred to the Wharton School of Business, from which he launched his career at General Electric as an auditor. During the 1950s and 1960s, the erstwhile lightbulb company founded by Thomas Edison reinvented itself as a conglomerate, expanding into such diverse fields as computers, nuclear energy, medical products, and financial services. As Jones rose through the corporate ranks, his acumen for financial accounting and broad-ranging business sense dovetailed perfectly with the corporation’s larger objectives. He became vice president of finance in 1968 and president and CEO four years later.5

His background in finance and position at the helm of the country’s leading conglomerate made Jones a particularly forceful ambassador for tax reform centered on capital accumulation. Addressing the Business Roundtable’s 1975 annual meeting in Manhattan, Jones laid out the dire straits that American industry faced. In the previous twenty years, he explained, nonfinancial corporations had acquired enormous levels of debt to fund their operations. The trend had accelerated since the late 1960s, and such firms now owed, on average, “almost two dollars for every dollar of net worth.” Over the next few years, GE’s economists predicted, the nonfinancial sectors would require a total of more than $300 billion per year to pay for “plant and equipment expenditures and working capital.” But given the disastrous state of the industrial economy, Jones continued, “[t]here is no way the industry is going to raise that kind of money under the present tax policies, unless it is to go deeper and deeper into debt—assuming it could find willing lenders.”

“Facing these financial dilemmas,” Jones told his Roundtable colleagues, “businessmen will simply seek to close the gap by lowering their overall capital requirements. You know this from your own experience. They will reduce their investment in plant and equipment; they will cut back inventory spending; and they will cut back their financial asset holdings. The result in all cases is reduced business activity, more unemployment, slower growth in productivity, and the kind of chronic inflation and stagnation that the American people won’t stand for.”

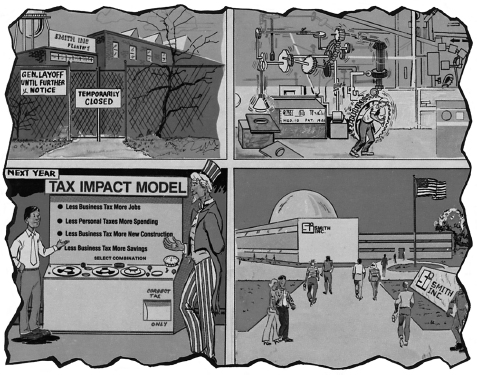

Figure 7.1. This four-panel cartoon, which graced the cover of the National Association of Manufacturers’ “Tax Impact Report” in the late 1970s, succinctly expressed many business leaders’ arguments about taxes. In the top two panels, high taxes force the factory to lay off workers, curtail output, and rely on inefficient and outdated machinery. Any combination of lower personal and corporate taxes, the bottom panels argue, would yield greater consumer spending, more hiring, and transformative reinvestment, ultimately paving the way for a prosperous future. Courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library.

“Therefore,” he concluded, “we simply must have changes in the national priorities.” First, he insisted, Congress had to reduce the federal budget deficit. By selling government bonds to cover its budget shortfalls, the federal Treasury effectively crowded private companies out of the debt market, Jones argued in the Harvard Business Review. Since the U.S. Treasury could always undercut corporate bonds on price, “business will have to go to the end of the line for leftovers in capital.” The second key to avoiding the slow death of American industry, Jones told the Roundtable CEOs, lay in corporate tax policy. Only by “reducing the tax burden on industry”—and thus permitting companies to retain more of their profits—could business “generate the funds it need[ed] to restore health to this economy and provide future growth in jobs and income for the American people.” Specifically, Jones exhorted his colleagues to promote tax reform that would “direct more of the nation’s resources into the modernization and expansion of our productive capacity.”6

Within a few years, advocacy by men like Reginald Jones spawned a political coalition in Congress dedicated to bolstering capital accumulation and industrial reinvestment by promoting the somewhat technical and dry concept of “accelerated depreciation reform.” In the summer of 1979, a bipartisan and multiregional group of legislators led by New York Republican Barber Conable and Oklahoma Democrat Jim Jones introduced legislation in the House to speed up the schedule by which corporations could claim write-offs for capital expenses on their income taxes. “The proposed bill,” boasted Theodore Brophy, the CEO of telecommunications giant GTE who had by then taken over the Roundtable’s Taxation Task Force, “was arrived at after approximately eight months of discussion and negotiations, with the full participation of the business community.”7 Although the measure failed to become law during the Carter administration, it fast emerged as business’s “top tax legislative priority,” as NAM president Alexander Trowbridge described it in 1980, until Ronald Reagan incorporated it into his signature tax cut in 1981.8

The complex and arcane notion of using asset depreciation to encourage capital formation grew from the peculiar nature of corporate taxation and the role of deductions. Like individuals, corporations can deduct certain expenses from their taxable income. But since the goal of corporate taxation is to target profits, not revenue, the universe of potential deductions is far vaster, including such expenses as labor costs and equipment. To reduce taxable profits, corporate accountants thus seek to write off as many operating and capital expenses as they can. Since 1909, when Congress first passed a corporate income tax (technically an excise tax based on income until the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913), policymakers recognized that the buildings and equipment that companies used would gradually wear out, lose value, and need to be replaced. To account for this fact, the first income tax laws permitted firms to set aside a “reasonable allowance” to replace such assets and deduct the cost from their tax burden, even if they did not spend money on the asset during a given tax year.9 Beginning in 1934, the Treasury Department required accountants to spread out such deductions over what was called the asset’s “usable life.” Accountants and tax attorneys calculated a piece of equipment’s worth and divided by the number of years the company could reap a financial gain from it, creating a system known as the “straight-line deduction.”10

Since at least the 1940s, however, lawmakers recognized that they could manipulate this aspect of the corporate income tax code to encourage certain behavior by private firms without reducing taxes on corporate profits. During the run-up to America’s entry into World War II, for example, the Second Revenue Act of 1940 created “accelerated amortization,” which allowed companies to write off the entire cost of constructing factories to produce war materiel, even as the government raised overall corporate taxes on “wartime profits.” During the postwar reconversion to a peacetime economy, similar provisions encouraged companies to invest in defense-related research laboratories that became integral to scientific development during the early Cold War. Finally, in 1954, tax reformers established a universal system of accelerated depreciation, which allowed a broader range of corporations to claim larger deductions earlier in the asset’s life, thus reducing their taxes in the short term and freeing up funds for reinvestment. As historian Thomas Hanchett has argued, Congress intended the new system to spark capital investment in machinery and buildings among manufacturing firms, but by including commercial property as well, the law prompted a tremendous boom in real-estate development, especially suburban shopping plazas, in the 1950s.11

The business community strongly backed the 1954 reforms, as well as subsequent acts in 1962 and 1971 that further sped up depreciation schedules, arguing that Congress should accelerate the write-off schedules even more. Support was particularly strong among large, capital-intensive firms, especially extractive and manufacturing companies, which generally had higher ratios of capital expenses to operational expenses and thus benefited more from the write-offs. Smaller firms tended to prefer the simplicity of straight-line deductions, reasoning that the added administrative expense of paying more accountants to figure out their taxes did not justify the value gained by deferring tax payments. The real problem lay with what the NAM called the “myriad of rules, formulas and regulations” that beset the corporate tax code, including depreciation schedules that varied across more than 130 asset classes, including some but not all types of assets. As a representative for both large and small manufacturers, the NAM argued that if the tax code were simpler, smaller firms would also take advantage of the accelerated depreciation schedules and thus have more capital to reinvest in their enterprises.12

The legislation introduced by Barber Conable and Jim Jones in 1979, officially called the Capital Cost Recovery Act, sought to appease both large and small business interests by streamlining and accelerating asset depreciation. Backed by the Business Roundtable, the NAM, the Chamber, and many trade associations, the bill proposed just three classes to encompass all depreciable assets, with three corresponding time frames for write-offs. Companies could depreciate buildings over ten years, vehicles over five years, and equipment over three years. Such simplification earned the proposal its common shorthand: 10-5-3.13

10-5-3 inspired optimism among many business leaders because it focused lawmakers’ attention on productivity and investment rather than sheer corporate profits. Indeed, Conable later wrote that he supported the bill precisely because it aimed at “improving industrial competitiveness by encouraging more investment in capital goods rather than reducing corporate taxes in ways that would increase profitability.” “Profits,” as the Chamber of Commerce reminded its members, remained a “four-letter word” for a good number of voters, and many lawmakers worried about appearing too beholden to wealthy business interests. Accelerating the depreciation of capital assets, however, reframed business’s campaign for tax relief around productive capabilities and job creation. In a clever cloaking maneuver, the arcane accounting procedure reduced corporations’ tax burden while avoiding the public scrutiny that would have accompanied direct reductions in the corporate tax rate. Such political framing, as well as the tremendous lobbying orchestrated by business groups, garnered the 10-5-3 legislation significant support in the summer of 1980, when the Roundtable confidently predicted victory.14

Accelerated depreciation was not to be, however, at least not under a Jimmy Carter presidency. After reading a Treasury Department estimate that the bill would reduce tax revenue by $50 billion, the president reversed his earlier support and came out against the measure because he opposed inflating the budget deficit by giving corporations a break on their taxes. In particular, Carter chastised the bill for unfairly privileging heavy industry and manufacturing—which he called “special interests”—at the expense of less capital-intensive industries, despite the bill’s support from some small business groups. Without support from the White House or Treasury, the bill languished in the Ways and Means Committee and died. The push for accelerated depreciation, the backbone of the capital accumulation movement within the business community, would have to wait for another political moment.15

THE “SUPPLY-SIDE” TAX CUT

The campaign for depreciation reform has faded into the obscure recesses of America’s collective political memory perhaps because tax accounting strikes most people as dreadfully boring but also because a far more widespread antitax movement overshadowed policy debates in the late 1970s. Like the business leaders who rallied around capital accumulation, the coalition for massive cuts to personal income taxes believed that lower taxes paved the way for economic stimulus. But the core support for cutting individual taxes lay outside the rarified air of corporate meetings and the Harvard Business Review. During the late 1970s, a combination of high inflation, prohibitive interest rates (thirty-year fixed mortgages averaged around 15 percent in 1980), and widespread antigovernment sentiment sparked a nationwide tax revolt. Taking their cue from California’s Proposition 13 in 1978, which dramatically reduced property tax rates and slashed funds for government services in the process, tax reform campaigns took shape in more than twenty states. The antistatist populism that underlay this activism drew both intellectual and organizational support from the spread of the “supply-side” movement.16

During the late 1970s, a coterie of conservative economists and policymakers hailed themselves as proponents of “supply-side economics,” a theory, they argued, that directly opposed Keynesian demand-side economic management. While Keynesians promoted the use of taxation and government spending to manipulate aggregate demand and steer a path between inflation and unemployment, supply-siders argued that economic policy should instead focus on stimulating supply: the companies that produced goods, the workers who put labor into that production, and the investment needed to expand the volume of goods and services generated by the economy. To its ardent defenders, such a shift in policy focus represented a revolutionary break with the politics of welfare, corporate subsidies and bailouts, regulations, and labor unions. According to David Stockman, a young Republican from Michigan who entered the House of Representatives in 1977 and later ran Reagan’s Office of Management and Budget, the “supply-side solution … required the radical dismantling of state-erected barriers to economic activity.”17

Despite such revolutionary talk, “supply-side doctrine” was in truth an artful repackaging of conservatives’ longstanding critique of demand-oriented fiscal policy and reflected a social vision reminiscent of nineteenth-century producerism. Stockman’s complaints about market dislocations and preferential incentives would have resonated sonorously at nearly any business association meeting since the late nineteenth century. Moreover, supply-siders’ claim that high taxes discouraged work and investment resurrected the basic economic philosophy of business tycoon Andrew Mellon, the treasury secretary who helped engineer substantial reductions in tax rates under three Republican presidents in the 1920s. Ironically, mainstream commercial Keynesians had long argued that lower taxes generated economic stimulus both by increasing consumption and by encouraging productive investment; liberal Democrats made such arguments forcefully, for example, during the debates that led to the Kennedy/Johnson tax cut in 1964. Nonetheless, while supply-side economics may have been derivative and unoriginal as a policy vision, it gained substantial traction as a polemical and rhetorical tool. Low-tax evangelists like Jude Wanniski, the Wall Street Journal editor who did more than anyone else to proselytize the doctrine, successfully aroused public passion and quickly constituted a powerful political coalition.18

For all their angst over government spending, subsidies, and welfare, the self-identified supply-sider activists of the late 1970s worked hardest to reduce federal income tax rates. The cornerstone of that policy initiative, which ultimately became the central feature of Ronald Reagan’s 1981 tax law, was an economic theory known colloquially as the “Laffer Curve.” According to a legend (apparently invented by Jude Wanniski), University of Chicago economist Arthur Laffer illustrated his claim that lower taxes could actually raise tax revenue by drawing his eponymous curve on a dinner napkin. Although Laffer later recalled that the dinner in question had occurred at a nice restaurant that used cloth napkins, the elegant simplicity of his model and Wanniski’s folksy propagandizing made for a compelling argument. Placing tax rates on the x-axis and government revenues from those taxes on the y-axis, Laffer claimed that the government would receive no revenue when tax rates were zero, for obvious reasons, but also when tax rates reached 100 percent, since no one would go to work if all his or her income were taxed away. As one followed the curve up from a 0 percent tax rate, revenues would increase, but at some point they would decline again as the curve turned back down and reached zero again when taxes reached 100 percent. The inverse U-shaped Laffer Curve thus predicted that if tax rates had already passed the point of peak revenue, reducing tax rates would actually generate more revenue. No one could say for certain where that magic point lay—that is, at what point did the disincentive to work outweigh the higher tax rate—but conservative supply-siders believed the current tax code had gone beyond it. Cut tax rates, they claimed, and people would work more.19

In 1978, Representative Jack Kemp (R-NY) and Senator William Roth (R-DE) gave legislative form to the Laffer Curve with a bill to reduce all fourteen federal income tax brackets by 10 percent per year over a period of three years, which its sponsors erroneously called a 30 percent across-the-board cut in tax rates.20 Although the supply-siders shared business leaders’ devotion to economic growth, savings, productivity, and investment, their proposed tax solution differed from the 10-5-3 plan in both form and function. Accelerated depreciation schedules, industrial executives hoped, would spur capital formation by manipulating the existing tax regime. By hacking tax rates “across the board,” the supply-siders believed, the Kemp-Roth bill upended the existing regime. Although 10-5-3 focused explicitly on capital investment—that is, the actual “supply side” of the economy—true believers like David Stockman chastised the business bill as a special interest sop, philosophically akin to price controls or the minimum wage, that disrupted “natural” market forces by privileging capital-intensive firms (exactly as Jimmy Carter claimed).21 Kemp-Roth, on the other hand, promised to remove government impediments to work and prosperity. In the language of its supporters at the conservative Heritage Foundation, the bill would make “leisure, consumption, and tax shelters relatively more expensive” than going to work, creating a robust engine for economic growth.22

Supply-siders’ rejection of 10-5-3 underscored an important intellectual rift between many business conservatives and the newly hatched supply-side movement. Traditional conservatives, including most business leaders, argued that a tax rate cut of the size Jack Kemp proposed would exacerbate the budget deficit by decreasing tax revenues. Few took comfort in Laffer and Wanniski’s claim that cutting taxes could actually generate greater revenues right away. Indeed, Stockman later confessed that the Laffer Curve had been mostly a metaphor for the economic bounty that low tax rates would yield by promoting economic growth and, thus, a larger tax base. In the short run, the tax cuts could never pay for themselves. Stockman himself confronted that harsh arithmetic reality directly when, as Reagan’s director of OMB after the 1981 tax cuts passed, he faced the Sisyphean task of reducing federal spending to compensate for lost revenue—and he failed.23

During the 1980 Republican primary, Ronald Reagan became an early convert to supply-sider theory and the Kemp-Roth tax cut, which jibed well with his populist politics. His challengers for the nomination, however, bristled at the breach of budgetary orthodoxy. Liberal Republican John Anderson, a congressman from Illinois, declared that Reagan’s promise to cut taxes, increase military spending, and still balance the federal budget was only possible using “blue smoke and mirrors.” Business leaders largely agreed; while few backed Anderson, most preferred either John Connally, former Texas governor and Nixon’s treasury secretary, or Texas oil developer George Herbert Walker Bush. The only “anti-Reagan” candidate who remained standing in the spring of 1980, Bush channeled the collective business community’s derision when he dismissed Kemp-Roth as “voodoo economic policy” during a primary debate.24 Instead, the former congressman whose résumé included stints as ambassador to China and head of the Republican National Committee, proposed relatively modest tax cuts to both corporate and personal rates, as well as the 10-5-3 plan and an investment tax credit for businesses. Tax cuts focused on business, the patrician Texan argued, represented the true “supply-side philosophy” because they were “directed at increasing supply—not demand.” Indeed, in Bush’s more accurate usage of the term “supply side,” protecting the interests of business and promoting investment necessarily entailed rigidly balancing the budget, a goal Kemp-Roth appeared to undermine.25

Bush’s intransigence did little to charm the Republican front-runner Reagan, and it signaled a much deeper schism brewing between business conservatives and supply-siders over the tax issue. Finishing the primary season in second place, the Texan managed to maintain enough goodwill to become Reagan’s vice-presidential running mate after former president Gerald Ford declined the spot at the convention in Detroit, and the political fence-mending that such a ticket required mirrored a similar rapprochement between the divergent tax-cutting factions. The GOP platform in 1980 technically endorsed both Kemp-Roth and 10-5-3, but it made no secret about where the party’s priority lay: Republicans put calls for the individual tax cut front and center, lauding it with glowing language about “fairness to the individual,” while they buried the details of accelerated depreciation deep in the bowels of the long document.26 To the chagrin of fiscal conservatives and the heads of major industrial corporations, Reagan chose the populist tack, embracing the politics of “tax revolt” and riding a wave of white middle-class anxiety into the presidency.

THE SHORT UNHAPPY LIFE OF REAGANOMICS: FROM ERTA TO TEFRA

Arriving in Washington with what he interpreted as a powerful mandate to shake up the nation’s tax system, Ronald Reagan worked quickly in the winter of 1981 to form a political coalition around the two complementary planks of his economic plan: a major tax cut (the Economic Recovery Tax Act, or ERTA) and significant reductions in government spending (the Gramm-Latta Omnibus Reconciliation Act). Although congressional Republicans had made great strides in the election, riding Reagan’s coattails to their first Senate majority in twenty-six years and gaining nearly three dozen seats in the House, the new president faced a difficult political task. Conservatives and many liberals supported the idea of reducing the tax burden, but deficit hawks—especially in the business community—cautioned that excessive tax cuts would bust the budget. Moreover, interest groups of all political stripes voiced different ideas about exactly where to cut the budget, how much to reduce taxes, and on whom.

“The President has proposed a far-reaching program that calls for a reduction in Federal government spending, taxation and regulation and a stable, consistent monetary policy,” declared Theodore Brophy, CEO of GTE and chairman of the Business Roundtable’s Taxation Task Force, and “[t]he business community feels strongly that all four parts of the economic recovery plan are essential.”27 Despite Brophy’s presumptuous claim to speak for all businesspeople, he accurately gauged the broad support among top executives, conservative think tanks, and trade and employers’ associations for the general tenets of what quickly became known as “Reaganomics.” ERTA, the tax cut bill, included both the Kemp-Roth personal income tax rate reductions and 10-5-3, which also went by the acronym ACRS, for Accelerated Cost Recovery System. In the spring of 1981, the Roundtable, the NAM, and the Chamber of Commerce all sprang into action, using their well-tested lobbying techniques to generate grassroots enthusiasm for the plan. Roundtable CEOs, for example, mailed thousands of informational packages to constituent companies and other contacts, bragging to White House staffers that the message had been “very well received” throughout the business community.28

No business leader distinguished himself more in the fight for Reaganomics than Chamber of Commerce president Richard Lesher, who told Chamber members that the program marked “a real chance for historic change” and implored them: “Don’t let it slip away.” The country’s largest business organization orchestrated mass mailings to thousands of executives, Washington lobbyists, trade and professional association directors, and heads of local chambers of commerce, urging them to organize mail and phone campaigns, meetings, and personal contacts with members of Congress. In addition, the Chamber distributed editorials by Lesher, issued an “Action Call” to its network of 160,000 members, and sent dozens of leaders and staff members to testify on Capitol Hill. Such efforts won Lesher considerable gratitude from the White House; staffers praised his group as “more active than perhaps any organization” in “fully endorsing every aspect of the President’s program.”29

Lesher’s zeal for the tax bill grew from deeply held convictions. A business school Ph.D. who had run many organizations, both government and nonprofit, but never a private company, the Chamber president shared more in common with supply-side ideologues than with many of the executives who rallied around 10-5-3 but fretted about budget deficits. “Balancing the budget is not the primary reason for reducing government spending,” one Chamber publication argued. “It is more important to reduce Federal competition with private citizens and businesses for scarce resources.” At the White House, advisors saw tremendous strategic possibility in Lesher’s unbridled advocacy. Because the Chamber of Commerce had long cultivated an image as the mouthpiece for “Main Street” small businesses and “mom and pop” enterprises, administration officials concluded that its enthusiastic support for Reaganomics would demonstrate “broad-based support” from “workers, consumers, tax-payers and small business.” Getting the tax cuts through a Democratic Congress would be difficult enough without the stigma that they appealed only to big, wealthy firms, and the Chamber could help bridge that political gap.30

The White House’s decision to grant Lesher and the Chamber a privileged position was not lost on the heads of other business associations. Complaining to White House aides James Baker and Edwin Meese, NAM president Alexander “Sandy” Trowbridge warned that unilateral meetings with one organization risked weakening the “cohesive strength of [the business] coalition.” “To ignore other parts of that coalition, including NAM, the Business Roundtable, the National Federation of Independent Business, and the American Business Conference, is to deny the President a full spectrum of business views,” he opined.31 Neither the NAM nor the Roundtable placed nearly the same priority on the supply-side cuts as did Lesher and the Chamber. Small business owners, including many manufacturers at the NAM, generally preferred lower tax rates to accelerated depreciation, both because they had relatively lower capital needs than large firms and because many paid taxes on their small businesses according to the individual tax brackets. Although the wealthy industrialists who led large corporations would certainly benefit personally from lower individual tax rates, their political allegiances in the early 1980s still aligned with the long-term interests of their firms. Indeed, many corporate leaders supported the personal tax cut more out of political opportunism than supply-side ideology or personal gain; for them, it represented the price they had to pay to keep their real prize, the 10-5-3 accelerated depreciation plan that would help their companies, in ERTA.32

Despite this tension between supply-siders and business-oriented tax cutters, the White House successfully tapped the full lobbying power of organized business groups to help push ERTA over the finish line during the summer of 1981. Mobilizing their deep networks of local business owners, community organizations, and other activists, corporate lobbyists launched what House Speaker Tip O’Neill (D-MA) called “a telephone blitz like this nation has never seen” in favor of the president’s economic package.33 On July 26, Congress passed the Gramm-Latta budget, cutting approximately $140 billion to more than two hundred government bodies, primarily in public aid and job-training programs. (The law also increased military spending by 9 percent for FY 1982 and authorized the Pentagon to expand its budget by 8 percent per year thereafter, dramatically reducing the savings.) Three days later, the House of Representatives passed Reagan’s tax cut, defeating a milder proposal by the House Democratic leadership, especially Ways and Means chairman Dan Rostenkowski (D-IL). The final bill, scaled back slightly during negotiations with Republican deficit hawks, reduced tax rates 5 percent in 1981 (starting on October 1), then 10 percent per year in 1982 and 1983. It also lowered the top marginal rate from 70 to 50 percent; reduced the capital gains tax rate to 20 percent; indexed tax brackets to inflation beginning in 1985; reduced the maximum estate tax from 70 to 50 percent and exempted all estates valued below $600,000; and, to the joy of the capital accumulation crowd, accelerated depreciation schedules for corporate income taxes according to the 10-5-3 model.34

The ink was hardly dry on Reagan’s tax cut, however, before the tumultuous politics of deficits and economic stagnation reconfigured the national debate. Before the first 5 percent cut even took effect on October 1, the economy dipped yet again into recession, and by the winter of 1982 White House economic advisors, and eventually the president, grew convinced that the tax cuts would not provide the economic cure-all that supply-siders had promised. The deteriorating economy severely cur-tailed tax revenues, and Reagan’s campaign promise to cut taxes, expand the military, and balance the budget by 1984 increasingly looked like “voodoo economic policy” after all.35

Adding to the political turmoil, growing strife over the budget acquired a bipartisan tone, in fervor if not quite in economic rationale. Liberal Democrats, for their part, argued that the Gramm-Latta budget primarily cut welfare, unemployment benefits, and food stamps, placing the burden of recession unjustly on the shoulders of the poor.36 Business conservatives, on the other hand, complained that however they fell, the budget cuts were too small to offset the coming tax reductions. The Business Roundtable’s Policy Committee predicted that the “large projected budget deficits” for the next three years “create[d] the possibility of continued high interest rates,” which would “delay reasonable recovery from the current economic slowdown.”37

But what could be done to restore balance to the budget? For many conservative business and financial leaders, notably those associated with nondefense industries, military spending appeared a logical first target. In a 1982 fiscal policy statement, Roundtable leaders claimed that the defense budget, like anything else, should be evaluated “on its merits, and directly in relation to its contribution to military capability and the Soviet threat—to reaffirm that it is all essential and will be put in place at minimum cost.” The heads of the American Stock Exchange agreed, telling pollsters that they “overwhelmingly favored cuts in defense spending,” at least by slowing its growth. Such pleas fell on deaf ears at the White House, however. A staunch Cold Warrior, President Reagan categorically rejected calls to streamline military spending. “Defense … is not a budget issue,” he famously told his budget team. “You spend what you need.”38

If defense cuts were out, business leaders reluctantly began to reconsider the severity of the supply-side tax cuts. Again, Roundtable CEOs took the lead. In a declining economy, they reasoned, capital accumulation became more important than ever. In the winter of 1982, Roundtable chairman Clifton Garvin (Exxon), Taxation Task Force chairman Theodore Brophy (GTE), and three other Policy Committee members met the president to pitch a “mid-course correction” to the Reaganomics juggernaut. The troop of executives, which included leaders from the energy, defense, telecommunications, and financial services industries, acknowledged the supply-sider creed that “high marginal tax rates reduce the incentive for capital investment and productive effort.” Nevertheless, they insisted, the effect was “a matter of degree” and far outweighed by “the need for a steady and significant reduction in the deficit.” While lower taxes as a matter of principle might be nice, the CEOs urged Reagan to consider “a stretchout of the 10% July 1983 individual tax-rate cut as a ‘last resort’ method of raising additional revenue.”39

For Reagan, however, the deep cuts in personal tax rates represented a sacred cow, the bedrock on which his entire economic vision rested. Thus with defense cuts and tax rate increases off the table, and with little desire to spend political capital on even harsher budget cuts in the years leading up to a reelection campaign, the president found himself quickly running out of options. Republican senators and White House advisors began to pressure him to at least consider some type of tax increase. At first Reagan resisted, writing in his diary: “Damn it our program will work & it’s based on reduced taxes.”40 By the spring of 1982, however, the president’s economic advisors finally persuaded him to pursue legislation that raised taxes, but only if he could do so while still retaining his precious cuts to marginal rates. The key, according to chief of staff James Baker, one of the administration’s loudest deficit hawks, lay in closing tax loopholes and eliminating exemptions, generating greater revenue without changing tax rates. And as it turned out, the weight of such changes would fall disproportionately on corporations.41

Reagan thus agreed to support the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (TEFRA), which became the largest peacetime tax increase to that point in American history by generating more than $98 billion in new tax revenue over three years through the skillful manipulation of the tax code’s detailed minutiae. In addition to limiting deductions and exemptions, TEFRA also repealed or rescinded many of the gains corporate lobbyists had worked into ERTA as a condition for their support, including the investment tax credit, safe-harbor leasing (designed to reduce corporate taxes by spreading tax credits among companies), and, most galling, about one-third of the accelerated depreciation benefits. According to political scientist Cathie Martin, approximately half of TEFRA’s revenue came from changes to the corporate tax code.42 To be sure, economists debate whether corporations really “pay” corporate income tax or whether they simply pass along those costs through higher prices or lower dividends to shareholders, so to say that business paid half of the cost of TEFRA is potentially misleading. Nonetheless, the law undeniably targeted the corporate tax code and corporate leaders rightly interpreted it as a loss, both as an accounting and a political matter. “Business,” GTE chief Theodore Brophy opined the next year, “received a small share of the Economic Recovery Act of 1981 benefits, [but] wound up with a large share of the various tax increases … enacted since 1981.”43

Brophy’s lingering bitterness reflected the heated debate that ripped through the once-unified community of organized business groups in the months before TEFRA passed in the summer of 1982. As the possibility of a deficit-fighting tax hike grew increasingly real that spring, the long-simmering tensions between supply-side and capital-accumulation oriented business leaders finally boiled over. Representatives from the Business Roundtable pleaded futilely for Reagan to leave the corporate tax provisions in ERTA alone and instead to delay the final 10 percent personal tax cut. When Reagan demurred, the group in turn refused to endorse TEFRA as a compromise, although its chairman, Clifton Garvin of Exxon, publicly insisted that the Roundtable had not “broken” with the administration and still supported the “basic principles and objectives of the President’s program.” Leaders at the NAM privately agreed with the Roundtable that deferring the marginal rate cuts served business’s interests more than changing the corporate code, but the organization publicly stuck by Reagan on the sanctity of the individual cuts and reluctantly promised to back the administration’s corporate tax hike. The National Small Business Association and several trade associations for realtors and builders, whose small and midsized members gained more from lower marginal rates than preferential provisions in the corporate tax code, also pledged loyalty to Reagan and TEFRA. The National Federation of Independent Business, a more ideologically conservative organization for small companies, withheld its support for several months out of principle, but it eventually backed the administration as well.44

Political divisions over raising taxes blossomed not only among but also within business associations. Despite its near-constant remonstrations about the perils of budget deficits, the Roundtable’s Policy Committee divided over whether to accept a reduction of 10-5-3 and other capital-forming provisions of ERTA. Some members steadfastly opposed the notion of balancing the budget on the back of heavy industry, while others, like General Electric, provoked the ire of manufacturers by lobbying to repeal ERTA’s safe-harbor leasing provisions.45 In another instance, the CEO of Texaco—a member of the Roundtable but not its powerful Policy Committee—wrote to Treasury Secretary Donald Regan in March to express his disappointment that the group’s stated position seemed to contradict the president’s priorities. Had he been asked, the executive explained, he would have rejected that position. Regan, former Merrill Lynch CEO and past member of the Roundtable’s Policy Committee, understood the complexities of the organization’s dynamics. He forwarded the Texaco letter to his boss, hoping President Reagan would “find encouragement in the support Texaco and other businesses are giving to the economic program,” even if their representative organizations appeared intransigent.46

As TEFRA made its way through Congress in July 1982, the Reagan administration worked to sustain a coalition of most Democrats and a handful of deficit-phobic Republicans to combat the strong antitax forces, particularly within the GOP. Frustrated at the Business Roundtable’s unwillingness to lend its clout to the effort, Treasury Secretary Regan lobbied his former colleagues directly, urging them to climb onboard not on TEFRA’s merits but rather on the political optics involved. Ronald Reagan, he pointed out, was deeply committed to exactly the type of investment-oriented, antiregulatory, free-market capitalism that the Roundtable had been created to defend. It would “be some time before you will encounter a President who so strongly shares your convictions.” To lobby in favor of TEFRA, Regan exhorted, was to work for Reagan himself and show support for “his ability to keep restraints on the irresponsible spending instincts of the Congress.”47

Despite Regan’s efforts, Roundtable CEOs remained conflicted, prompting a less diplomatic approach by Senate Finance Committee chairman Robert Dole (R-KS), a staunch fiscal conservative. Dole headed the drive to recruit enough Senate Republicans, who held a 53– 47 majority, to join the Democrats on TEFRA, even as his wife, White House Assistant for Public Liaison Elizabeth Dole, spearheaded the administration’s outreach to business groups. In an angry memo to Roundtable chairman Theodore Brophy, Senator Dole declared that “silence on the part of the Business Roundtable means opposition” and could only signify that the group was “primarily concerned about retention of special tax benefits” rather than the public good. Faced with such an affront to its public purpose, the Roundtable begrudgingly yielded; two days after they received Senator Dole’s letter, its leaders issued a tepid endorsement of TEFRA, despite what they called “serious reservations.”48

The war over TEFRA erupted more ferociously at the Chamber of Commerce, where divisions over tax policy nearly ripped the venerable organization apart. President Richard Lesher’s ebullient supply-side beliefs led the group to resolutely reject any backtracking from the ERTA tax cuts, whether on businesses or individuals. Ideologically, the Chamber pushed the supply-side credo even further, denying the very essence of fiscal conservatism: that budget deficits led to higher interest rates,

thus slowing economic growth by limiting borrowing and stifling capital investment. According to a Chamber brochure, interest rates had “never shown any direct connection to either tax increases or the size of the deficit” and thus deficit reduction could not justify tax increases. As the chief source of opposition to TEFRA, Richard Lesher and the Chamber’s public affairs department drew on the populist antipathy to government that Ronald Reagan had ridden to power but, ironically, now turned that spirit back against the president. TEFRA’s tax increase on business would “only encourage more spending,” Lesher said, clearly articulating the conservative mantra later known as “starve-the-beast”—that only lower tax revenue could restrain a spend-happy Congress.49

But the Chamber of Commerce of the United States was bigger than one man, and many corporate executives on its governing board dissented from Lesher’s purist ideology. Opponents included W. Paul Thayer, the chairman of the Chamber’s board in 1982 and chairman of the defense, aeronautics, and heavy industry conglomerate LTV Corporation. Possibly swayed by his own industry’s close relationship with the Defense Department, Thayer concurred with his fellow executives and the White House that the problem of deficits outweighed the ideological quest for small government. In August, Thayer announced that he and a slim majority of the board of directors had broken with Lesher and threw their weight behind TEFRA. An embarrassing public turf war immediately broke out, as both Lesher and Thayer claimed to speak for the entire organization. Lesher, backed by prominent conservative CEOs like Donald Kendall of PepsiCo, inveighed against the tax bill, Reagan, and Thayer, insisting to the press that most of the Chamber’s thousands of members unilaterally opposed the bill. Thayer, meanwhile, convened a directors’ meeting to vote on a new formal position in support of TEFRA, which he telegrammed to Reagan.50

Paul Thayer, like the members of the Roundtable’s Policy Committee, understood the political value of cooperating with government, especially a conservative one, even if doing so violated the tenets of “free-market capitalism.” The aftermath of the Chamber schism proved his point. Lesher enraged the administration, particularly by refusing a direct request by Vice President Bush and White House counselor Edwin Meese to use the Chamber’s television studio for pro-TEFRA publicity. In retaliation, the White House announced that it no longer welcomed Lesher’s input and would “work with the Chamber but only through Paul Thayer,” as one staffer reported. For his loyalty, Thayer later received an appointment as deputy defense secretary, a position he held until an insider-trading scandal prompted his resignation in 1985.51

In mid-August, TEFRA faced its final legislative gauntlet. House members and senators met in conference to reconcile their different versions of the bill and lobbyists worked hard to influence the details. Although the Democratic leadership and organized labor backed the effort, many Democrats in both houses of Congress worried that voting for a tax increase would hurt their reelection prospects. Although stridently conservative supply-siders in the Republican caucus, led by Jack Kemp and Georgia representative Newt Gingrich, lobbied hard against the measure, many Republicans straddled the fence and looked to their party’s leader for reassurance. President Reagan knew that shepherding the bill to its final form would require discipline in the ranks and that he could not do it alone. To marshal proactive support from business, Elizabeth Dole organized an ad hoc group of thirty-five business leaders called the Deficit Reduction Action Group. Within that body, midsized financial and other fast-growth industries took a pronounced leadership role advocating for deficit reduction, while the representatives of heavy industry, so devoted to capital accumulation, continued to drag their feet.52

As the final votes on TEFRA approached, the White House realized that a relatively weak effort by reluctant corporate lobbying groups would prove insufficient to sway the key swing votes. In a reversal of the usual pattern—whereby business associations undertook massive telephone blitzes to pressure politicians—Reagan himself worked the White House phones, exhorting business leaders to ask their senators for a yes vote. Over the course of a week in mid-August, the president personally phoned two dozen executives and association heads, often more than once. He called Roundtable Policy Committee members as well as the presidents of the NAM, the National Federation of Independent Business, and other groups but, as promised, not Richard Lesher. After hearing the president’s reassurances that he still believed in “the need for capital formation and investment,” the Roundtable’s Theodore Brophy affirmed his group’s support. Jack Welch, who had succeeded Reginald Jones the previous year as CEO of General Electric—a company Elizabeth Dole described as “the most politically sophisticated firm in town”—also weighed in. “Despite the burdens it does impose on both business and individuals,” Welch told Reagan, “the bill is needed and will have our support.” On August 19, the reconciled bill cleared the House 226 to 207 and the Senate 52 to 47. Out of 244 House Democrats, 123 voted in favor; of those, 96 had voted against ERTA the year before. Half of House Republicans (89 of 191) sided with Reagan. In the Senate, the results were more lopsided: Only 9 Democrats voted with the majority, as many liberals objected to the spending cuts conservatives had demanded in exchange for their support. Two weeks later, a bruising bipartisan fight behind him, the most famous enemy of taxes to sit in the White House signed the bill to raise them.53

“HALT THE DEFICIT”: TAXING AND SPENDING IN ECONOMIC RECOVERY

The struggle over TEFRA cast a pall over Reagan’s relationship with the heads of major employers’ associations, who could no longer pretend that their defense of free enterprise remained wholly unified. In the debate’s aftermath, the administration recognized the need for damage control and actively solicited input from corporate leaders and associations, even making peace with Richard Lesher by including him in a large meeting of Roundtable CEOs, free-trade lobbyists, and Chamber executives with Reagan early in 1983. For their part, organized business leaders responded favorably, if somewhat hesitantly, to the overtures. According to a spokesman for the NAM, “a great reservoir of support for the President” remained, but businessmen were “obviously … less supportive than before the deficit.”54

Yet for all the ill will it generated, TEFRA ultimately did little to slow the growth of the budget deficit. The difference between the federal government’s tax revenue and spending outlays increased, in nominal terms, from $128 billion in 1982 to $208 billion in 1983, rising from 4 percent to 6 percent of gross national product; although it dipped slightly to $185 billion in 1984, the deficit remained above $200 billion and 5 percent of GDP through 1986. Yet despite years of dire predictions by fiscal conservatives that deficits would prompt sky-high interest rates and permanent recession, the economy began to recover in 1983 and roared back to life in time for Reagan’s resounding reelection in a forty-nine-state electoral knockout. In a timely decision, Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker abandoned strict monetary targets and permitted the money supply to expand just as TEFRA made its way through Congress. The consequent reduction in interest rates spurred consumer borrowing and spending, and, Keynesian economists pointed out, deficit spending further stimulated demand and growth. The recession of 1981 and 1982 finally wrung inflation, which had peaked at 13.5 percent in 1980, out of the economy, and it remained low during the recovery; the inflation rate fell below 4 percent in 1983 and, with rare and fleeting exceptions, has remained below that level ever since.55

But while the national economy as a whole recovered, the recession of the early 1980s had proved devastating and, in many cases, permanently debilitating to the nation’s industrial manufacturers. As economic historians have argued, private debt and mass consumption—rather than industrial revival—really drove the post-1983 expansion. Low domestic interest rates, a strong dollar, and freer flows of international capital combined to create a massive surge in imports, leading the country’s balance of trade deficit to quadruple between 1982 and 1986. This debt-financed boom generated tremendous growth in financial services but did little to rehabilitate traditional manufacturing and export-focused industries. Ironically, however, the internal politics, priorities, and discourses within the organized business community continued to focus on a more restrictive set of domestic policy concerns rather than the large-scale changes in the national economy. Licking their political wounds after the TEFRA fight, corporate leaders trained their sights ever more sharply on the same issues that had guided them since the early 1970s: regulatory reform, investment-oriented corporate tax policy, counterinflationary monetary policy, and, more than ever, the budget deficit.56

Early in 1983, the Business Roundtable created a formal task force on the budget, distinct from its Taxation Task Force, and appointed Robert Kilpatrick, CEO of Cigna, to run it. The head of a giant health insurance provider, formed in 1982 when the Insurance Company of North America merged with Connecticut General Life Insurance, Kilpatrick expressed a particular interest in reducing federal spending on entitlements, especially Medicare and Social Security, which he believed competed directly with the private insurance industry.57 Upping the attack on the budget later that spring, Theodore Brophy announced the Roundtable’s “major campaign … for restraints on Federal spending of all kinds.” The group urged Congress not only to reduce spending on Social Security and defense but also to implement “a 12-months freeze on most nondefense discretionary programs, permanent limitation of cost-of-living adjustments for non-means-tested entitlements, and an effort to find further long-term savings in Medicare.” At the same time, Brophy, by then a co-chairman of the Roundtable, denied rumors that his group favored another tax increase. “Nothing could be further from the truth,” he insisted. The Roundtable had merely acknowledged “that revenue beyond the budget projection might be required to deal with the deficit,” but the number one priority remained “spending reductions.”58

Industrial executives at the Business Roundtable clamored particularly loudly for deficit reduction because of their conviction that fiscal imbalances lay at the heart of American manufacturing’s declining international standing. Even as the economy recovered, domestic manufacturing continued to suffer. To be sure, most of the pain fell on the workers who lost their jobs because managers and executives increasingly moved production to regions with lower labor costs, first in the less unionized southern and western states and then, increasingly, abroad. By the end of 1987, 1.7 million fewer Americans worked in manufacturing than had at the end of the 1970s. Yet while workers bore the brunt of this transition, industrial executives also grew anxious about the competitive pressures they faced in an ever more globalized economy. Overall corporate profits failed to reach their 1960s levels even at the height of the 1980s expansion, and manufacturers felt the strongest pinch. The strong dollar relative to the yen, for example, made Japanese cars far less expensive for Americans. “American companies are losing sales to Japanese firms,” railed Lee Morgan, CEO of the heavy industry corporation Caterpillar Tractor, “not because of cost, quality, or service, but because of the unearned price advantage due to the undervalued yen.”59

Underlying the decline of manufacturing and the country’s mounting trade deficit, executives argued, was the federal budget deficit. Public debt, many business leaders charged, “crowded out” private borrowing. “[E]very dollar that the Federal Treasury borrows,” Cigna’s Robert Kilpatrick claimed, “is a dollar that is not available to put people to work.” Moreover, budget deficits created high interest rates, which led to the overvalued dollar. Meeting with Reagan late in 1984, Lee Morgan proclaimed that “the extraordinary strength of the dollar is responsible for over half of the deterioration in the U.S. trade position” and that the “major cause of this currency misalignment is the U.S. budget deficit.” Although economists debated the validity of Morgan’s argument, his fervent appeal to Reagan typified the angst that beset industrial executives. The panic over the deficit ran deeper than platitudes about fiscal solvency; it reflected far-reaching anxiety over the long-term decline of manufacturing.60

Fiscally conservative policymakers sympathized. In 1984, Republican senators Robert Dole (KS) and Pete Dominici (NM) led a contingent of budget hawks to persuade Reagan once again to raise taxes. In the political and lyrical spirit of TEFRA, they proposed “DEFRA,” the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984, which further altered loopholes in the corporate and individual tax code to make what they called a “down payment” on the deficit without raising Reagan’s cherished marginal tax rates. Partly because of the improved economy and partly because TEFRA had exhausted many conservatives’ passions and energy, the public debate over DEFRA was notably more muted. Much to Dole’s chagrin, lobbyists from the National Association of Realtors successfully negotiated for preferential tax breaks for the real estate industry, but the traditional big-business lobbying powers remained mostly on the sidelines. Chamber of Commerce economists warned that the recovery was not strong enough to support higher taxes and thus opposed the bill, but they did so with little verve. The NAM, on the other hand, announced support for both DEFRA and a balanced budget amendment to the Constitution, which Reagan had urged but Democrats had blocked during the TEFRA debate. Executives at the Roundtable likewise held back, only inserting themselves late in the process to support a handful of specific details. In particular, they joined the successful push, led by the original 10-5-3 enthusiast Barber Conable in the House, to reduce large corporations’ tax liability for profits earned abroad on exported goods. As the next chapter explores in detail, the relative weakness of the traditional voices of organized business reflected changing dynamics within the American business community. Information technology, finance, and other nonmanufacturing industries like insurance and pharmaceuticals represented the biggest growth sectors by the mid-1980s, but those industries had not traditionally taken leadership roles in major business associations. Similarly, the growth of multinational corporations in the same years complicated issues of trade and tax policy, creating divisions within groups like the Roundtable.61

In addition, the debates over DEFRA strained relations between business associations and more philosophically libertarian political activists—the women and men often called “movement conservatives” who had mobilized through think tanks in the 1970s and who, by the 1980s, populated many corners of the Reagan administration. Rather than uniting business conservatives in a principled defense of free markets, tax and deficit politics exposed businesspeople’s parochial interests, to the consternation of true believers. Economist Murray Weidenbaum, chairman of Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisors in 1981 and 1982, became an outspoken vehicle for that frustration, chastising business groups for putting their own interests ahead of free enterprise in the tax debates. Known for his wit, Weidenbaum claimed business’s self-interest led to “Pogo economics”—like Walt Kelly’s cartoon possum, conservatism had “met the enemy, and he is us.” Clamoring for preferential tax treatment, he maintained, was just as anticapitalist as regulations, minimum wages, or any other government interference in the market.62

For all the teeth-gnashing it inspired, DEFRA—like TEFRA before it—did little to redress the imbalances in the federal budget. According to deficit historian Iwan Morgan, the two laws combined generated less than a third of the revenue lost due to ERTA between 1984 and 1988. To the chagrin of many deficit hawks in both political and business circles, however, surveys suggested that most Americans did not worry nearly so much about the deficit as the political class did. As Congress negotiated its next federal budget in the spring of 1985, Roundtable executives announced their intent to return to grassroots lobbying by coordinating a nationwide letter-writing campaign to generate a groundswell of public concern about the deficit. Under the battle cry “Halt the Deficit—Write Now!” Roundtable executives distributed millions of prewritten postcards for their employees to mail to Congress. Americans perusing the May issue of Reader’s Digest found a removable postcard, co-sponsored by the Roundtable and the magazine, to send to Washington, saying: “I want you to reduce federal deficits now…. I’m willing to do my share.” According to the Roundtable, nearly one million readers mailed in those cards, and many reported “attaching letters amplifying their views.”63

Prudential CEO Robert Beck, the Roundtable chairman who spearheaded the effort, claimed that the group had “never undertaken a grassroots campaign of this magnitude” and believed that doing so was essential to “demonstrate to our lawmakers that there’s strong public support for doing what must be done to get these deficits under control.” Reagan’s reelection and the economic recovery seemed to have removed the urgency from the deficit issue, and Congress appeared preoccupied with revenue-neutral reform to the tax code. (That movement led to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which the next chapter discusses.) In that environment, Beck worried that deficit reduction would get lost in the shuffle. Personal contacts with legislators by CEOs and Washington Representatives helped the cause, he told Roundtable executives, but—as business had learned during its successful mobilizations in the late 1970s—lawmakers responded more to messages from constituents than to direct lobbying. As a grassroots campaign, therefore, Halt the Deficit aimed both to incite public outrage and to provide proof of that fervor. In that spirit, its literature and promotional material dedicated substantial space to shrill and apocalyptic claims about interest rates and trade deficits, keeping the specifics to a minimum. Although Roundtable members and their lobbyists worked hard behind the scenes to promote particular changes to federal appropriations, they remained purposefully nonspecific in public about what to cut. Vaguely calling for a retrenchment of defense, entitlement, and social spending, for example, Beck claimed “hard choices” had to be “shared by all sectors of society except the poor.”64

Although Robert Beck claimed that Halt the Deficit was “a first” for the Roundtable, its methods in fact mirrored the indirect lobbying efforts that the group had deployed against the Consumer Protection Agency, labor law reform, and other issues. As with those earlier mail barrages and public information campaigns, measuring the exact effect of the effort of such lobbying on the legislative process is impossible. Nonetheless, the contrast between the group’s stated goals and the legislative outcomes suggests that the Business Roundtable did not enjoy the same measure of influence in the mid-1980s that it had boasted ten years earlier. Roundtable CEOs devoted substantial, if unquantifiable, resources to the Halt the Deficit campaign, which they genuinely believed would tilt the budget process in their favor. Working closely with Bob Dole and other budget hawks, they lobbied furiously for major reductions in federal spending, including a freeze on cost-of-living adjustments for Social Security and other federal pension payments. In the end, however, Democrats in Congress—backed by a White House that refused to expend political capital on such unpopular provisions—passed a budget in 1985 that, in the words of a bitter Robert Beck, “failed to genuinely address the problem of unbearable budget deficits.”65 Thereafter, the Roundtable’s Halt the Deficit campaign quietly faded away.

A FRAGMENTED LOBBY

The tangled politics of taxation and budget deficits thus proved a bridge too far for organized business groups in the 1980s. In the years after 1985, the budget deficit remained a major political issue and business leaders, most vocally at the Roundtable, joined fiscal conservatives in Congress in a nearly constant clamor for reductions in spending. A final resolution to the budget problems of the 1980s, however, would have to wait for a new president, George H. W. Bush. Despite his campaign promise of “no new taxes,” Bush ultimately agreed to work with, and not against, congressional Democrats, coupling spending cuts with increases to marginal tax rates in the Budget Act of 1990. Although the Business Roundtable did not participate significantly in the deal between Bush and the Democratic congressional leadership, it embraced the outcome, which one member called “probably the best one could expect from a politically divided government.” Such a lukewarm endorsement likely came as cold comfort for President Bush, however, who faced intense blowback from latter-day supply-siders and other antitax conservatives in his party. As numerous political observers have suggested, the Budget Act of 1990 did more than anything else to doom Bush’s chances for reelection, although it, along with tight fiscal policy under President Bill Clinton, effectively put the country on the road to eliminating its budget deficit entirely by 1999.66

Well before Clinton defeated Bush in the election of 1992, however, the contentious politics of taxes and deficits severely undermined the claims to unity between mobilized business associations and their ideological allies within the conservative political establishment. While America’s most significant industrial competitors, Japan and Germany, largely avoided populist tax revolts or indeed major changes to their tax regimes in the 1980s, the shifting dynamics of industrial capitalism in the United States upended traditional alliances as the competing agendas of small-government conservatives and business-minded fiscal conservatives sparked intense internecine conflict.67 In that ideological battle, the powerful tradition that fueled calls for “small government” ran squarely against the harsh reality of deficit spending. To their chagrin, fiscal conservatives realized over the course of the early 1980s that it would prove impossible to “starve the beast” if the beast could continue eating simply by putting its food on a credit card. As a result, many American industrial leaders eschewed the siren call of “movement conservatism,” at least in its most ardent manifestation.

The politics of taxation, particularly the tale of two tax cuts that this chapter has explored, suggest another important division between industrial leaders and other conservative activists, at least through the TEFRA battle of 1982. By casting their lot with accelerated depreciation in opposition to reduced marginal tax rates, executives like Reginald Jones of General Electric aligned themselves politically with their firms’ economic interests. Although highly compensated individuals like the men who ran the country’s largest corporations certainly had much to gain from lower taxes, the political ethos they embodied reflected the mind-set of professional managers. As the eminent business historian Alfred Chandler argued, the professionalization of management and the rise of a managerial class in the second half of the nineteenth century kept American business focused on the long game. Under earlier models of firm governance, Chandler contended, family ownership encouraged short-term planning and immediate rewards. Professional managers, on the other hand, benefited more from their firms’ long-term success, since stability provided a guarantee of their future salary. The debates over tax policy in the late 1970s and early 1980s revealed that the managerial mind-set remained dominant among many politically active executives.68

But the shifting plates of global capitalism and the growing instability of American business, particularly the industrial manufacturing sector, would soon render such company fidelity a historic relic. As the American economy recovered from the recession of the early 1980s and confronted more directly the new world of globalized trade and finance capitalism, both the operations of America’s large corporations and the nature of the men and women who stood at their helms would change. As we will see in chapter 8, a new generation of executives began to occupy the corner offices; unlike the men who founded the Business Roundtable, most of whom had spent their careers with single companies, the CEOs of the 1980s and 1990s increasingly boasted degrees from business schools, where they learned general and transferable management skills. At the same time, investment portfolios and short-term stock positions came to eclipse long-term production goals, and by the turn of the century the fierce devotion with which industrial leaders clamored for accelerated depreciation would become difficult for most businesspeople to comprehend.

Cultural changes within the upper ranks of American business thus overlapped the tumultuous politics of taxes and deficits in the mid-1980s and played a role in organized business groups’ diminished capacity to shape budget policy. In earlier fights against wage-price controls, labor reforms, and social regulations, representatives of different sectors within the business community successfully overcame barriers to collective action by working together against a common enemy—the liberal, labor-oriented Keynesian state. But once conservatives gained control of the federal government and had to make hard choices about exactly how to cut spending and allot tax cuts, conflicting priorities within and among business groups, and with other conservatives, weakened their collective influence. Yet even as their organizational unity began to fracture, industrial executives remained fixated on the link between fiscal policy and the state of American manufacturing. Reaganomics, which sought to implement a “business-oriented” policy by freeing markets and minimizing the role of the federal government, thus achieved an ironic legacy by fixating industrialists’ attention on the budget while other factors hastened the country’s industrial decline. As the final chapter argues, business leaders’ inability to respond politically to issues like slackened productivity and foreign competition ultimately marked the passing of their unified movement as new types of industries came to dominate American politics.