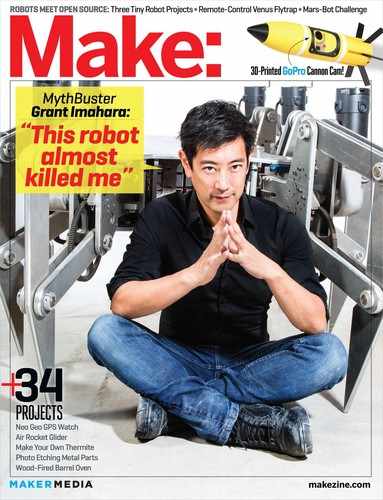

THE SELF-TAUGHT SCULPTOR

Written by Jon Kalish

JON KALISH is a Manhattan-based radio reporter and podcast producer. For links to radio docs, podcasts, and stories on NPR, visit Kalish Labs at jonkalish.tumblr.com.

EBEN MARKOWSKI’S METALWORKING SKILLS ARE ROOTED IN HIS FATHER’S CAR RESTORATION SHOP.

EBEN MARKOWSKI IS NOT A STARVING ARTIST. That’s because he’s dedicated to reducing overhead and living life in its simplest terms. While Eben has previously managed to cobble together a living by doing stints of excavator work and restoring fancy Italian sports cars at his family’s auto shop, the 38-year-old Vermont sculptor, who makes nearly life-sized renditions of animals, would like to do nothing but make art. He just may get to the point where he can do that thanks to an Asian elephant and its calf.

“We live paycheck to paycheck,” Eben says, referring to his wife, Heidi, a chef and woodworker, and many members of the animal kingdom who live on their nearly 13-acre homestead in Panton, Vt., about a mile from Lake Champlain.

You’d think that two Vermonters who are not exactly rolling in dough would be reluctant to spend several thousand dollars a year feeding and providing medical care for enough critters to fill Noah’s Ark. Yet the Markowski spread has ducks, chickens, sheep, goats, a cow, dogs, and a cat. The cow, Petunia, was brought to the Markowskis by “a veterinarian with a heart” when a local farmer had left her for dead. Other adoptees, including an old ram named Chester, came from Shelburne Farms, an environmental education center north of this dairy farm area.

Eben’s connection to animals goes way back. “You could look at my mother’s photo albums and the earliest photos show me holding a frog or a crayfish or a worm,” he says.

His ability to create realistic sculptures of animals also dates back to his childhood. His father, Peter, remembers Eben at the tender age of three announcing one day, “I made a rabbit.” When his father asked to see it, little Eben opened his hand and revealed what his father remembers as “an unbelievable, small, to-scale rabbit” made out of Play-Doh.

Eben makes a very good hourly wage working for his father, something akin to what a master plumber earns. But the sculptor is trying to minimize his time in the family auto shop, Restoration and Performance Motorcars, because of his commitment to sustainable living. Eben dismisses the shop’s focus on rebuilding old Ferraris and other exotic sports cars as “dinosaur work. We should really be doubling down on what would sustain us.”

And yet Eben acknowledges that the family business has played a pivotal role in his career as a sculptor. It was inside the two burgundy-colored barns his father built for auto restoration in Vergennes, Vt., that Eben had the tools and workspace to sculpt. And it was at the family business that his first patrons stumbled upon his works in progress.

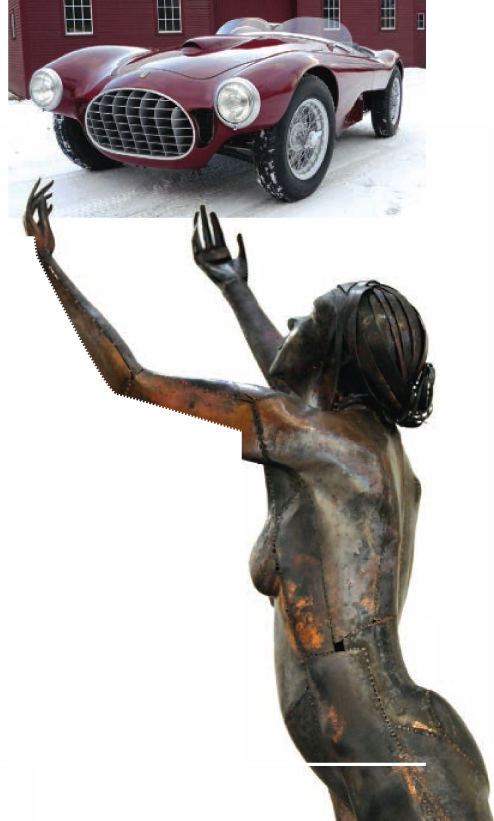

“My father’s car shop was a tremendously fortunate place to be,” he tells me as we walk past a 1954 Ferrari 750 Monza, an Aston Martin from the late 1930s, and a spotless Ford Woody station wagon from the 1940s.

Eben and his younger brother Stephan were in the auto shop at a very young age. Eben was about 10 when he was taught to weld. Having a father who fixed things all the time was a factor. “You don’t throw something away, you fix it,” he was taught as a boy.

Jerry Swope

Today Eben jokes that he and his brother were indentured servants when they were boys but then quickly stresses that they loved working on cars. There were times when their father didn’t let customers know just how young the shop’s “mechanics” were.

“My father would put the phone to his chest and say, ‘Guys, come on.’ And he’d shoo us out from under cars because a client was coming in and he didn’t want the client to see two little kids putting in a drive shaft,” Eben chuckles.

On one occasion a client of the car restoration business became a client of the sculptor. When Eben was 20 years old, he was about halfway through completing a giraffe sculpture when a man and his wife stopped in.

“I remember them driving by and abruptly pulling in and asking what it was that I was doing,” the sculptor recalls. “Fortunately for me, they saw the potential in it. One of the most flattering things for an artist is when someone wants something that you’re making. They can see where you’re going and you have inspired them to want it.”

Before he finished the first giraffe, another couple rolled in to the shop and commissioned a second giraffe. At about 18 feet tall, it turned out to be bigger than the first one.

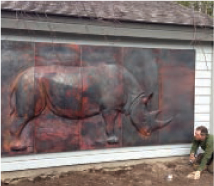

Eben also did a five-panel rhinoceros relief made with sheets of copper roofing hammered on wooden forms he made using a handheld grinder with a blade attached. It measures 6 feet by 12 feet and is 5 inches deep.

While Eben was working on the rhino, he took on a challenging car project: He spent a year and a half making an entire new body for a priceless 1951 Ferrari, working from a handful of half-century-old grainy photographs of the vehicle and employing traditional techniques used in the ’50s. His artistic aspirations dovetailed nicely with the needs of his dad’s business and created a unique niche for him.

“Instead of having to say, ‘Oh, we need to have this door panel made. We need to go to Boston or California to find someone to do sheet metal,’ I happened to be there teaching myself how to do this for sculptures,” Eben recalls.

Eben “not only understands animal forms but mechanical forms and machines and movements,” observes Homer Wells, a painter and tinkerer who lives in Monkton, Vt. “Eben’s powers of observation are absolutely unbelievable, and his mechanical voodoo is beyond belief,” Wells says.

Those skills allow him to live what he considers a more environmentally responsible life, one where frugality, doing-it-yourself, and recycling are central tenets. This is evident in his handmade home. “Eben welds and I’m a woodworker. The two of us together can make almost anything,” Heidi says proudly.

It’s also apparent in his tools and building materials. An unapologetic dumpster diver and self-confessed collector of scrap material, Eben modified a 1981 Ford backhoe that originally came with four different levers to operate its rear shovel. He cannibalized a discarded printing press for bearings and gears to make a linkage that enabled the shovel to be controlled with two levers instead.

A work in progress, his root cellar roof is actually half of an old fuel tank made of ¼-inch-thick steel. His youngest brother, Judd, cut the 16-foot-long tank with an oxyacetylene torch. The half tank weighs around 2,500 pounds and sits on the root cellar’s stone walls, which are 4 feet high and as thick as 3 feet in some spots. Standing inside the root cellar, Eben looks up at the ceiling’s orangey-brown rust patina and declares, “I think rust is totally underrated.”

There are rebar hoops welded to the root cellar ceiling to hang garlic for storage. Heidi planted 9,000 heads to grow the crop commercially. A portion of their new 720-square-foot sculpture studio will be used for garlic drying.

Heidi helped her husband build the 24-foot by 30-foot studio onto the side of their house, which took about six weeks. It has 100-year-old hand-hewn hemlock timbers for framing and 10mm polycarbonate greenhouse glazing for walls, creating a solarium effect that makes the studio 25° warmer than outside.

The studio also has a 10-foot-high door, which Eben points out is big enough for an elephant. In winter of 2013, the sculptor went to work on his latest commission: a life-sized Asian elephant and its calf. He expects to complete the main elephant in early summer 2014 and then get started on the calf.

As for going back to work in the family car business, Eben says he won’t rule that out if he’s in a financial bind or his family really needs him for a project. “We try not to give him the mundane tasks because his head isn’t in it,” his father explains. “But when it’s a huge challenge or something really off the wall, he’s all about that.” ![]()

+ See more of Eben's work at ebenmarkowski.com