15

Symbolic Action: Language, Ceremonies, and Settings

Given the choice of influencing you through your heart or your head, I will pick the heart. It’s your head that sends you off to check Consumer Reports when you are thinking of purchasing a new car. It’s your heart that buys the Jaguar, or the Porsche. It’s your head that tells you that political campaign speeches cannot be believed or trusted, but it’s your heart that responds to the best oratory, and makes you refuse to vote for people who come across as “dull,” as though that were a reason to vote or not vote for a governmental representative. “People are persuaded by reason, but moved by emotion.” 1 We exercise power and influence, when we do it successfully, through the subtle use of language, symbols, ceremonies, and settings that make people feel good about what they are doing. A friend once remarked that it is management’s job to make people want to do what they need or have to do in order to make the organization prosper. In a similar fashion, it is the job of people interested in wielding power and influence to cause others to feel good about doing what we want done. This involves the exercise of symbolic management.2

Symbolic management operates fundamentally on the principle of illusion, in that using political language, settings, and ceremonies effectively elicits powerful emotions in people, and these emotions interfere with or becloud rational analysis. Murray Edelman noted, “It is not uncommon to give the rhetoric to one side and the decision to the other.”3 Edelman further noted that political speech was a ritual that dulled the critical faculties rather than sharpening them.4 But it would be incorrect to think that using symbolism and language to make others feel good about the actions or decisions you require of them is somehow acting against their interests. If, after all, the actions or decisions are important and necessary, they might just as well feel good about them as not.

In this chapter, I begin by considering rational versus emotional approaches to persuasion and the exercise of power. I then describe and provide examples of each form of symbolic management in turn, beginning with the important issue of language, and subsequently discussing the use of settings and ceremonies in the exercise of power and influence.

RATIONALITY AND EMOTION

In all types of administration and in many organizations, training and skill building at all levels have been focused on the development of better decision-making capabilities. Moreover, decision-making capacity is assessed in terms of conformance to a rational model of choice. The rational analyst, with a command of facts, figures, logic, and analytical technique, has come to be revered in our society. We use phrases like “rocket scientist” to express both our wonder and our respect for these (often young) analytic wizards. The “whiz kids” of Ford Motor Company and the Defense Department’s systems analysis unit were among the first of the new breed of analyst, who spread this approach to management through a number of organizations. Robert McNamara at Ford Motor, and Tex Thornton at Litton Industries, were among the early practitioners and advocates. The following passage about McNamara, from David Halberstam’s book, The Best and the Brightest, well illustrates the features of the super analyst:

If the body was tense and driven, the mind was mathematical, analytical, bringing order and reason out of chaos. Always reason. And reason supported by facts, by statistics—he could prove his rationality with facts, intimidate others. He was marvelous with charts and statistics. Once, sitting at CINCPAC for eight hours watching hundreds and hundreds of slides flashed across the screen showing what was in the pipe line to Vietnam and what was already there, he finally said, after seven hours, “Stop the projector. This slide, number 869, contradicts slide 11.” Slide 11 was flashed back and he was right, they did contradict each other. Everyone was impressed and many a little frightened. No wonder his reputation grew; others were in awe. . . .5

One problem in exercising power in this manner is apparent already in the passage quoted from Halberstam. Power is exercised by a mastery of the facts, and by leaving others intimidated, awestruck at one’s brilliance and ability. But being in awe of someone does not always cause us to feel warmly about that person. We may admire the mental capacity and be struck with the acuity of the mind, but liking is not necessarily one of the feelings elicited. Forgetting for the moment our discussion about how facts can be produced to justify almost any decision, it is also the case that exercising power through intimidation, by overwhelming our opponents, is not likely to produce allies, or as many friends as we would like.

Humans are not computers, and emotion and feelings are important components of our choices and our activities. Our unwillingness to confront this reality about ourselves, as well as a fear of the emotional side of life, helps to explain why people are often uncomfortable reading about or discussing the use of political language, ceremonies, or settings. This is a part of us that somehow embarrasses us, something we would like to pretend doesn’t exist. But this very denial makes us more susceptible to emotional appeals. We are off guard, and therefore more easily swayed. My experience has been that people with training in engineering or business are more readily seduced by emotional appeals than people trained in literature or drama, who understand exactly the techniques being employed, and who therefore admire them but are not necessarily taken in.

We cannot see the dynamics of organizations just in terms of who wins, who loses, and the associated costs. These are important considerations, but we must remember that the consequences of actions and choices often have their origin in the symbolic, political actions that are taken to affect how people feel about the situation. Murray Edelman explained the complexity of political analysis:

Political analysis must, then, proceed on two levels simultaneously.

It must examine how political actions get some groups the tangible things they want . . . and at the same time it must explore what these same actions mean to the mass public and how it is placated or aroused by them. In Himmelstrand’s terms, political actions are both instrumental and expressive.6

POLITICAL LANGUAGE

I am reasonably certain that no readers of this book living in the United States will ever again face a tax increase. We may be subject to “revenue enhancement,” the reduction or elimination of “tax preferences” (such as deductions for mortgage interest, medical expenses, and so forth), or, best of all, we may once again experience the joys of “tax equity and reform.” Herbert Stein provided a lovely list of the magnitude of the tax increases passed under the Reagan administration, but never called “taxes” or “tax increases” at all:

Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act, 1982—$55.7 billion Social Security Amendments, 1983—$30.9 billion

Budget Reconciliation Act, 1987—$13.9 billion Tax Reform Act of 1986—$24.4 billion7

Who can be opposed to “tax equity and fiscal responsibility” ? Perhaps all of us, once we see how much such lofty words are taking out of our pockets. How was Reagan able to do all this and keep his image as a fiscal conservative?

Mr. Reagan retained his title as the world’s champion enemy of taxes, despite all the tax increases enacted with his concurrence during his regime. . . . The lesson for politicians seems to be that you can get away with raising taxes if you talk as if you didn’t do it.8

Language is a powerful tool of social influence, and political language is frequently vital in the exercise of power in organizations of all types. We perceive things according to how they are described in conversation and debate. This is why it is reported that Confucius, upon being asked what he would do if he were appointed to rule a country, replied, “The first thing I would do is to fix the language.” Morris noted, “Sharing a language with other persons provides the subtlest and most powerful of all tools for controlling the behavior of these other persons to one’s advantage.”9

Another classic example of the use of political language in national politics is the Windfall Profits Tax, passed in the waning days of the Carter administration—after the start of the tax revolt in California and just as Ronald Reagan was to be elected president on a program of less taxation and less government. The tax, which at the time of its passage was predicted to raise about $227 billion over ten years, was designed to capture for the government some of the economic benefits derived by the U.S. oil companies when the price of domestic oil was decontrolled and rose to the world market price. The tax, however, was not based on the profits of the oil companies, defined in the conventional way as revenues minus expenses. Rather, the tax was a sales or excise tax, based on the price of oil. This is why there has recently been talk of repealing the tax—oil prices have fallen so far that they have occasionally been below the trigger price, or the price at which the tax generates any revenue. Although there is some dispute among economists about whether corporate income taxes are shifted to consumers, there is more agreement that, depending on one’s assumptions about the elasticities of supply and demand, excise taxes fall heavily on the consumer.

How, then, could a $227 billion tax on consumers of oil and oil products be passed? Certainly not by calling the tax an excise tax, or an oil sales tax, or even the “Hard-Earned Profits Tax.” The successful passage of the tax depended in important respects on what it was called—the Windfall Profits Tax.” In a society in which public opinion polls show that many citizens do not understand the role of profits in the economic system, windfall profits are particularly odious. “Windfall” is defined as “an unexpected sudden gain or advantage,” 10 and how could anyone object to taxing something that was not really expected in the first place? Of course, many people well understood that this was not a tax on profits at all. The Wall Street Journal in numerous editorials called attention to the precise nature of the tax. But if you call something the “Windfall Profits Tax” often enough and long enough, the connotations of that name have effects emotionally, even if not intellectually, and these effects are potent.

Language is important in exercising influence, and it is the job of leaders and managers in organizations to get things done. It is, consequently, not surprising that many writers have noted the importance of using symbols and political language in the management task. Karl Weick wrote:

Managerial work can be viewed as managing myths, images, symbols, and labels. The much touted “bottom line” of the organization is a symbol, if not a myth. . . . Because managers traffic so often in images, the appropriate role for the manager may be evangelist rather than accountant.11

Tom Peters argued that “symbols are the very stuff of management behavior. Executives, after all, do not synthesize chemicals or operate lift trucks; they deal in symbols.”12 Nixon commented, “The leader necessarily deals to a large extent in symbols, in images, and in the sort of galvanizing idea that becomes a force of history.”13 In writing about leadership, Lou Pondy noted that one of the important tasks of leaders entails providing labels for activities and making them meaningful for organizational members:

. . . the effectiveness of a leader lies in his ability to make activity meaningful for those in his role set . . . to give others a sense of understanding what they are doing and especially to articulate it so they can communicate about the meaning of their behavior. . . . This dual capacity to make sense of things and to put them into language meaningful to large numbers of people gives the person who has it enormous leverage.14

One of the important questions raised by our discussion of symbolic action and political language concerns the value of proposing actions or choices using factual, rational analysis. Most of us believe we are well served by backing up our proposals with extensive quantitative rationales and analysis. In watching the videotape of British Steel making an important capital investment decision, executives and students often comment on how the project champion never seems to have or use any numbers, but instead relies on a variety of emotional appeals and interpersonal influence techniques. There are some situations that are, however, best handled in precisely that way. Particularly if the emotions tapped are potent, and if the project, or at least a decision that irrevocably commits the organization to the project, can be completed quickly, there are many advantages to arguing not with numbers but with symbols. Numbers can always be debated and disputed. If your numbers are challenged, studies may be proposed to try to determine whose assumptions are the more reasonable. The problem is that while this is going on, the project is losing momentum and time. It is easier to argue about numbers than about symbols, which provides at least one reason to use symbols either alone or in conjunction with analyses.

When Time Inc. considered launching TV-Cable Week, the people involved on the startup team felt that they needed a way to explain, succinctly and concisely, what the project was about in terms of its market potential. Preparing for a major presentation to the corporation’s highest-ranking executives, the five business-side players tried to come up with a simple way of presenting the project. One of them, a Harvard MBA graduate, suggested, “Why don’t we play this game we used to play at the B-School—If You Could Tell Them Just One Thing?”15 Then:

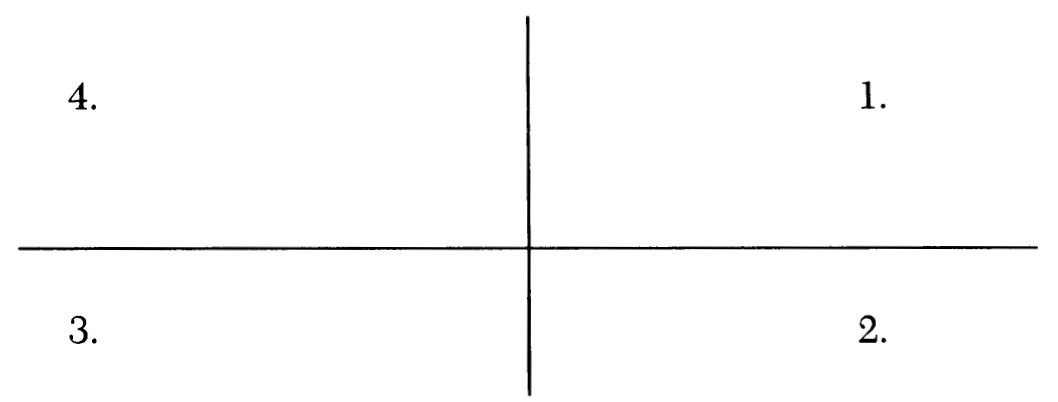

. . . one of the group . . . no one quite remembers who . . . drew two lines on a sheet of scratch pad paper, and set in motion a deal worth $100 million. First, a vertical line, then bisecting it a horizontal line . . .

To the right of the vertical line was the “free market,” in which magazines reached the reader by traditional means, such as newsstand sales. . . . To the left was the market for magazines co-marketed with cable operators. Above the horizontal line were the weeklies, below were the monthlies. . . . Then . . . one came to Quadrant 4, the co-marketed weeklies—with no competitors in there at all. A whole empty quadrant for the taking. . . . the ultimate executive memo: a document with no words at all, just two crossed lines on a piece of paper.16

The importance of finding that simple presentation of the concept for the magazine cannot be exaggerated; it was used at meetings of the corporation’s executive committee and the board of directors, and the ability to give symbolic representation to the concept was a potent force in pushing the project forward. Of course, no one in the company asked the obvious question: If there is one quadrant unoccupied, why? Maybe that quadrant is not commercially feasible (which turned out to be the case, at least at that time).

At about the same time, across the continent at another corporation, the importance and power of language was also being demonstrated. Fall of 1983 was a tough time for Apple Computer. At the end of September, the cover story of Business Week proclaimed IBM the winner in the personal computer wars. The Apple III had failed, Lisa was not selling well, and even Apple II sales had fallen, in anticipation of IBM’s launching of the Peanut, to be known as the PCjr. The sales force was concerned, and morale was low. In computer sales, moreover, “forecasts became self-fulfilling, for lost credibility meant fewer sales, and fewer sales meant bigger losses, and bigger losses meant lowered credibility, and on and on in what could only result in the whole business going spiraling down the drain.”17 At the fall sales meeting, motivating the sales force and the independent distributors in attendance was critical:

Jobs and Murray were sprawled on the floor of a hallway outside, writing Jobs’ speech. . . . Macintosh was an artificial arrangement of silicon and metal designed to manipulate electrons according to the strict rules of logic; but its appeal transcended logic, and so would his pitch for it. This was no mere “productivity tool” but a machine to free the human spirit. . . . It was a mystical experience. All you needed to use it—all you needed to respond to it—was your own intuition. And to sell it, Jobs had only to play to the emotions.18

Jobs’s speech, repeated at the 1984 annual meeting in January at which Macintosh was announced, focused on IBM’s mistakes—in not buying the rights to xerography, in not taking either minicomputers or personal computers seriously. Then, it turned to the hard times in the personal computer industry, and the fact that IBM wanted it all:

“Will Big Blue dominate the entire information age?” he cried at last. “Was George Orwell right?” “No!” they screamed. . . . And as they did so, an immense screen descended from the ceiling. In a sixty-second microburst [the 1984 commercial] the drama unfolded. . . . The sales conference was transformed in that moment—all defeatism banished, euphoria in its place.19

No change in Apple’s market position, no change in its technology, no change in its substantial bank account occurred because of that masterful use of symbolic management, either at the sales conference or at the annual meeting in Cupertino. What was changed was the organization, and how its employees (and competitors and potential customers) felt about it. That was all, and that was enough.

The skillful use of language tends to be rewarded in organizations. Having your own proposal seen as “clean,” “tight,” and “forward-looking,” and the alternatives viewed as “messy” and “indecisive,” will almost assuredly guarantee the success of what you have proposed. Language is also often used to take the sting out of what might otherwise be painful or difficult transitions in organizations. An automobile sales manager never talks about firings, only about “career readjustments.” At Stanford in 1990, we did not have administrative cutbacks with accompanying layoffs, but rather, “repositioning.” In a large medical care organization, there are no mistakes or malpractice, just PCEs (potentially compensable events).

Lyndon Johnson was a master at using symbols and language to make otherwise unpalatable situations appear better, and to motivate those around him. As Congressman Kleberg’s secretary, he had two assistants, one of whom was Gene Latimer. Latimer had wanted to come to Washington to be near his fiancée, but the work schedule of the office under Johnson’s direction left little time for romance. “He was allowed time off from the office to see her on Sundays after three p.m.—and only on Sundays after three p.m.”20 Johnson paid Latimer very poorly, as the money he saved on his assistants he could keep for himself. But when Latimer seemed at one point to be near rebellion, Johnson understood how to placate him with a symbolic gesture:

“He listened with sympathetic concern . . . then told me he had been thinking for some time on how to reward the excellent work I had been doing. He had finally decided that I merited having my name put on the office stationery as assistant secretary. As he described the prestige and glory of such an arrangement, I could see the printing stand out six inches.”21

The use of a title or some other symbolic reward to make people feel better about their position in the organization and about what the organization is doing is quite common, and also quite often successful, as Johnson’s efforts were with Latimer, who worked for him virtually all his life.

Political language works, in part, by calling “the attention of a group with shared interests to those aspects of their situation which make an argued for line of action seem consistent with the furthering of their interests.”22 And political language is often effective because people are judged by their intent, by the symbolism of what they are seeking to accomplish, rather than by the reality of what they are doing. George Gallup noted, “People tend to judge a man by his goals, by what he’s trying to do, and not necessarily by what he accomplishes or by how well he succeeds.”23

Language is such a powerful tool of influence that I often advise people to diagnose the language in their own organizations. It can tell them a lot about how the organization thinks about itself and its activities. As a consequence, language can be a potent predictor of behavior.

One of the more interesting diagnostics is the form of pronouns that one sees used in organizations. There are “I” and “me” organizations, and organizations that emphasize “we” and “us.” There are also organizations in which other persons and units within the firm are referred to as “they” or “them.” Not only can this language tell you something about the organization’s culture and health, the language itself can be important in exercising influence.

Consider the case of the split of a large Cleveland-based law firm, Jones, Day, Reavis and Pogue (JDR&P). A substantial part of the Washington office broke off when the managing partner of the firm, Alan Holmes, tried to remove Eldon Crowell and his government contracts group from the Washington office. The events that followed after Crowell was told he had to leave the partnership have many interesting aspects, but the use of language is particularly instructive. Both the Holmes group and the Crowell group distributed memoranda to partners and associates, trying to muster support and recruit for their side. Partners could, of course, either remain with JDR&P, or join the new firm, Crowell and Moring. I have obtained copies of both memoranda, and the differences in the use of language are striking. Recall that this is a contest for the loyalty and support of highly educated professionals in a firm that exists to sell professional services.

The Holmes or Cleveland group memorandum is addressed, “To the Washington Partners,” and it begins:

Appended hereto is a copy of the position paper we have this morning delivered to the members of the Washington Office Executive Committee.

Most of us . . . plan to be in the Washington Office for much of the day and we would be glad to talk . . . with anyone who would like to discuss further our national firm program.

The next page, headed “To the Partners of JDR&P,” reads, in part, as follows:

At the partnership meeting of the Cleveland office . . . I reported on the discussions. . . . Since that time I have been away . . . but I asked . . . to give consideration during my absence to all aspects of the problems raised. I now have their views . . . and believe it is appropriate now to give you my considered judgement of the situation.

I believe most of our partners recognize the dramatic changes in the nature of the demand for legal services. . . . Those corporate law firms which are limited to providing such conventional services will not, in my judgement, successfully survive the changes occurring in the modern corporate practice. Only those large firms which, because of their ability to respond on what I would term a transaction basis . . . will flourish in the future.

There are seven uses of a first person pronoun on the first page (six in the first paragraph), and nine by the end of the paragraph that continues from the first page to the top of page 2. Can you guess how the firm was managed—by an elected executive committee, or by a strong managing partner with virtual CEO powers? The answer is in the language. Perhaps more important, how would the language make you feel if you were an undecided Washington partner? Is a hand being extended to you, or are you being told by a parental figure about the world of law practice as he sees it?

By contrast, the Crowell group’s memorandum is headed, “To Our Partners in JDR&P.” It begins:

During the past three weeks, the members of the Washington Executive Committee and most of the partners located in Washington have spent considerable time discussing the relationship between the Washington Office and the remainder of our firm. The focus of those discussions has uniformly been on steps which might be taken to strengthen existing relationships . . . and move forward together with our friends and partners . . . to achieve more fully our common goal of building the best law firm in the United States. . . . our partners resident in Washington take great pride in their association with Jones, Day. . . . We expressed these views at a breakfast meeting. . . . We expressed also our sincere hope that this would be the first of many meetings. . . . We were disappointed to be told by Mr. Holmes of his conclusion . . . that the “Governments Contracts Group” is incompatible with his concept of the national firm.

The Cleveland memo is signed by five attorneys (named), with Alan Holmes listed first. The Crowell group memorandum is signed, “Washington Executive Committee.” There is no use of “I” or “my” in the Crowell group memo, and the tone is much more of reaching out, and less of lecturing. There are many reasons why Crowell and his colleagues did so well at attracting both partners and associates to go with them, but their use of language and the attitude it implied was clearly a significant factor that contributed to their success. These two memoranda provide a nice illustration both of how language can be used to diagnose power and governance structures, and how the use of language is a critical tactic in the exercise of power and influence.

CEREMONIES

Ceremonies provide the opportunity to mobilize political support as well as to quiet opposition. Ceremonies are occasions to help organizational members feel better about doing what needs to be done. They can also be used as part of larger political battles within organizations. There are a number of ceremonies, or ceremonial events, which occur regularly in organizations, ranging from annual meetings, sales meetings, training sessions, conventions, and other such gatherings to the replacement of high-level executives, retirement events, and celebrations of accomplishments. In each instance, the issue is what use is made of the ceremony. If symbolic reassurance is offered to a group to be co-opted, or if the ceremony is used as part of a political struggle, we need to ask whether it is successful in disarming the opposition.

Apple Computer’s 1984 annual meeting was, as we have noted, an example of the successful use of political language. It was a ceremony with significance on many levels. By closing down all of the facilities in northern California and providing transportation for all employees to attend the meeting, Apple signalled that this was an important event. The meeting was intended to build a sense of community in the company, by means of a celebration of the Macintosh. At that moment, however, with the Macintosh not yet introduced, Lisa doing poorly, and the Apple III withdrawn, Apple II was, obviously, carrying the company, and this fact was not recognized in the ceremony. By putting the Macintosh team at the front of the hall, having videos and other special recognition of the Macintosh team, and by focusing exclusively on the new machine, the ceremony further signalled to members of the Apple II division their second-class status and their diminished power in the organization.

Meetings are often held to reassure some group in the organization that it is important. The very holding of the meeting dedicated to that group provides some symbolic reassurance, but what occurs at the meeting is also important. Under Robert Fomon’s leadership at E.F. Hutton, the retail brokerage part of Hutton became increasingly dissatisfied with the direction of the firm. The division felt left out, unimportant, and ignored. Some years before, George Ball had established the Directors Advisory Council (DAC), “an elite group of successful Hutton brokers. . . . In theory, the DAC was meant to keep the Hutton board informed of the brokers’ thinking and lobby for changes on their behalf.”24 Of course, what it really involved was an attempt to make the brokers feel important and included in the organization’s governance. Unhappy with Fomon, the DAC called a meeting and demanded that he attend. The potential for a ceremony to cause the brokers to feel better both about him and the organization was there, but Fomon missed the opportunity:

By using the DAC meeting as a platform to appoint Miller as head of the field, Fomon would have diffused much of the anger and demonstrated he could be responsive to the field. But . . . Fomon had a different response. He simply turned around and left the meeting. He walked out. It was as if he couldn’t be bothered with these lowly stockbrokers and their petty whining.25

Conventions and special meetngs can, if used properly, both co-opt interests in the organization and signify relative power and status to everyone involved. Similar outcomes often occur in corporate training activities. Smart organizations involve their highest-level executives in training, evening discussions, or informal social events. Such ceremonies signify to the managers at the session that they are important to the organization. Even if they are not really considered in the organization’s top-down decision making, they will feel flattered by their contact with top-level people and their inclusion in events attended by important executives. What functions or what executives actually attend such events also helps to symbolize power and status in the organization. If quality is an issue and quality control personnel are rising in prominence, one would expect to see them at the training sessions as instructors or executives in residence, not just as participants. If the company is dominated by finance, then one can be sure that there will be financial presentations on the company’s reception by investors, and perhaps even explanations of how the capital markets work and how the company is valued. This latter focus has been a major theme at Westinghouse training, and it reflects that corporation’s conglomerate structure and highly financial orientation. In companies that face public affairs and public relations problems, such as insurance companies, representatives from those functions will play a larger role. In short, participation at training activities not only signifies the relative power of various groups, but from this very signification, helps to enhance that power at the expense of competing units.

Regular, ongoing meetings, such as those involved in budget, performance, or product review, likewise have ceremonial aspects, in which power, both departmental and hierarchical, can be displayed. Harold Geneen’s monthly review sessions with the business unit managers in International Telephone and Telegraph were notorious. By putting managers on the spot for their performance, Geneen maintained his own power. And in order to look good in front of their peers, the managers engaged in a competition to provide better results, at least as measured by ITT’s systems.

Hierarchical power, and loyalty to the boss, were displayed at meetings held in General Motors. De Lorean noted that high-level committee meetings became occasions for the top two or three people to demonstrate their power and authority:

In Fourteenth Floor meetings, often only three people, Cole, Gerstenberg, and Murphy would have anything substantial to say, even though there were 14 or 15 executives present. The rest of the team would remain silent. . . . When they did offer a comment, . . . it was just to paraphrase what had already been said by one of the top guys.26

Often, top executives would obtain precise facts and use them to intimidate subordinates during meetings, again reaffirming their power in the organization. A master of this was Frederic Donner:

One time in an Administrative Committee meeting he asked the head of GM Truck and Coach Division:

“How many buses did you build last month?”

The executive replied: “Approximately three thousand.”

Donner scowled and snapped back . . . “Last month you built three thousand, one hundred and eighty-seven vehicles.” Whatever the figure was, it was precise. . . . Donner was trying to make the point, “Look how I know this business. . . . Look what a mind I have!”27

Understanding that meetings are ceremonial occasions can help us gain the patience to sit through them, and even to obtain some enjoyment from the experience. Paying attention to the symbolic, as well as the substantive, content of meetings of all types can help us diagnose organizational power and influence and become more sensitive to the way it is played out in various settings.

Executive replacement and succession is often another important ceremonial occasion. For companies caught doing something illegal or improper, the replacement of executives can provide reassurance that the corporation as a whole does not tolerate such behavior and that things will be different in the future. In the early 1970s when illegal contributions to political campaigns and bribes to foreign governments to obtain business were discovered, the chief executives of both Gulf Oil and Northrop resigned. When E.F. Hutton was discovered writing bad checks and earning interest on the float, two high-level executives were forced out, although not the CEO. Someone had to be held accountable for the misdeeds, and this individual, in turn, had to be removed from the organization, as a form of ritual purification.

It is seldom the case that accountability for corporate misdeeds can truly be attributed to one or a few individuals. Corporations have shared cultures and standard operating procedures, which makes me skeptical that the firing of one or two people really makes much substantive difference. And indeed, in some of the organizations (such as aerospace firms) in which ritual firings occurred once, there were ritual firings again (and again) as additional instances of misconduct came to light. Firing high-level executives, particularly the president or CEO, can also signal to the world that things in the company are going to improve. It is said that managers in professional sports are hired to be fired—to shake things up and to assure the public that the ownership will not tolerate poor performance forever. A similar function is served by managers in business firms and other organizations as well. Indeed, recent studies show that at poorly performing smaller firms the replacement of the CEO by an outsider actually causes the stock price to advance compared to the market. 28 Thus, the market at least believes that replacement is a consequential event in the life of a corporation.

Succession is indeed a ceremony. If the company is to take advantage of the ceremony, it must release lots of information indicating that the problems are the fault of the individual being replaced. The choice of the successor, and his or her installation, should be accompanied by much public comment and display. The successor should be given a wonderful biography, so that the promise for the future seems very bright indeed. Although, as we have seen, Archie McCardell left the Xerox Corporation in poor financial shape, the announcements of his arrival at International Harvester made him appear as though he were the greatest business genius of the twentieth century. Companies never admit to hiring losers at the time they are hired, but always admit to hiring deficient executives at the time those executives are terminated.

The event of succession is also an occasion for the various political divisions within the organization to show their influence. Which particular group will the new executive represent? Because of the symbolic as well as substantive importance of the choice of organizational leaders, this decision is often highly political and hotly contested.29 When E.F. Hutton stopped appointing brokers as its CEO, there was concrete evidence that power in the firm had shifted away from the retail side. The appointment of John Sculley at Apple Computer was a signal not only that the company had grown up, but also that marketing and organization were seen as comparatively more important than technology. The appointment of an accountant to head Bethlehem Steel in the 1970S signalled that the company was now perceived as a collection of financial assets; passing over a contender from the steel side of the business conveyed the decline of steel not only in industrial America but also at this particular firm.

There are many occasions for ceremonies, and these events are important because of their connotations about power and influence in the organization and their effect on various organizational constituencies. The importance of ceremonies and language in the development and use of power has sometimes led me to recommend acting, literature, or English classes to aspiring managerial leaders. Some of my colleagues think that Stanford MBA students are only looking for an easy grade when they take drama as an elective, but I often think these courses have more utility than many traditional alternatives.

SETTINGS

We have already discussed the way in which settings and physical space can be used to diagnose power distributions. The physical representation of power and influence can take on a life of its own, helping those in power to stay there and forming a bar to the aspirations of the less powerful. Even more interesting, however, is the way in which physical space can be used as a tool for the exercise of power and influence.

General Motors was, and probably still is, a very hierarchical organization. Power was concentrated at the top, with relatively little influence being exercised by lower-level participants. This concentration of power at the top was ratified by the design of the headquarters building:

In General Motors the words “The Fourteenth Floor” are spoken with reverence. This is Executive Row. . . . To most GM employees, rising to the Fourteenth Floor is the final scene in their Horatio Alger dream. . . . The atmosphere on the Fourteenth Floor is awesomely quiet. . . . The omnipresent quiet projects an aura of great power. The reason it is so quiet must be that General Motors’ powerful executives are hard at work in their offices. . . . It is electrically locked and is opened by a receptionist who actuates a switch under her desk in a large, plain waiting room outside the door. . . . GM executives usually arrive at and leave their offices by a private elevator located just inside Executive Row.

They [executive offices] are arranged in order of importance. . . . There is great jealousy among some executives about how close their offices are to the chairman and president. . . . All [offices] were uniformly decorated in blue carpet, beige walls, faded oak paneling and aged furniture . . . except for those of a few uppermost executives, who could choose their own office decoration.30

By contrast, Apple Computer was a less hierarchical organization, and power was less concentrated at the top. This was reflected in the office arrangements for the chief executive, John Sculley:

Sculley’s office was as unassuming and informal as his new wardrobe. A small, square room in the rear corner of the Pink Palace, it overlooked the car wash on one side and parking lot on the other. The furnishings were standard issue for Apple executives. . . . The wall that overlooked the area where his secretary sat was all glass, creating an illusion of openness.31

Hierarchical power differences are at once symbolized and created by physical settings. Think about the description of the two office environments—Apple Computer and General Motors. At which one are you, as an average manager, going to feel more like speaking with the CEO? At which are you more likely to feel as if you can challenge or question decisions? At which will you feel closer and more similar to the top executives? If you confront an imposing, intimidating physical setting, you will probably feel less powerful and influential than you otherwise would. In this way space creates power and influence as well as reflecting it.

Thomas Foley, the Democratic majority leader in the House of Representatives during Jim Wright’s tenure as Speaker, also had an office that he carefully constructed to reflect his view of his job:

The office was laid out like a living room, with a small desk, no larger than what a child might have in a bedroom, against a window; Foley’s job was to listen and he believed that a large desk, which conveyed authority and served as moat between listener and visitor, interfered with people speaking freely. He did not impose himself; he listened.32

Physical settings mark horizontal power struggles as well. When the Macintosh division was in the ascendancy at Apple, and the Apple II division was falling in influence, Apple II was exiled from Bandley Drive, corporate row, to a leased building a mile away, as Macintosh occupied their old space. And while that space had held some 200 employees when the Apple II division occupied it, the space was reconfigured for the Macintosh division to hold about half that many.33 The rise in power of the Macintosh group under Jobs was physically apparent, and the luxury of the division’s physical location, particularly its nearness to headquarters, gave it advantages in the struggle for corporate resources and attention.

At the interpersonal level, once again, space can be used to exercise power. There are power positions, such as at the head of the table, that tend to convey power immediately to the occupant. Having a large office, an imposing desk and desk chair, and an office arrangement that separates you from your visitors are all ways of subtly increasing your power.

Like language and ceremonies, settings, too, are important in the exercise of power and influence. As such, settings should be considered carefully and used strategically. Occupying space because it is available, convenient, or cheap seldom produces good results. It is necessary to be sensitive to the physical environment, not only for its effects on position in the network of interaction, but also for the impression of power or powerlessness that it conveys.

One reason that language, ceremonies, and settings are so important in the exercise of influence is because we are often scarcely conscious of their effects on us. The influence of appropriately chosen language, well-conducted ceremonies, and carefully designed settings can escape our conscious attention. And because of our focus on the rational and the analytic, we are likely to downplay their potency. How many of us would request another meeting place, or ask to have terminology corrected, in an important discussion over issues of great substance? But if we are not sensitive to the language, the ceremonies, and the settings, we may find ourselves at a power disadvantage without even being aware of it.