2•

The Marketing Toolkit

“Marketing is not the art of finding clever ways to dispose of what you make. Marketing is the art of creating genuine customer value.”

Philip Kotler

This chapter outlines the fundamentals of marketing and introduces the basic concepts and tools underpinning marketing strategy. A useful framework for planning is known as the marketing mix. This long-used marketing tool is explained and updated to integrate more recent marketing theory. Key principles of segmentation, targeting, positioning, differentiation and competitive advantage are explained, with information on how fashion designers create a distinctive signature style and determine a unique selling proposition for their brands.

What is marketing?

Marketing is intriguing in that it has been variously described as a business function, business philosophy and also as a management or social process. Marketing should really be viewed as a holistic system connecting a business with its customers. Professor Philip Kotler, who has been described as the godfather of modern marketing, believes that what makes a company is its marketing. Kotler considers marketing to be both a science and an art. It is strategic and creative, requiring systematic research and analysis as well as innovation, intuition and gut instinct.

The range and potential of marketing can be almost limitless; it may start way before any product has been designed and continue long after a customer has purchased. This scope and multi-dimensional nature could make a clear definition appear rather illusive. However, the next section will address this issue by presenting four definitions that capture the essentials and simplify the complexities of marketing. The key points raised by the individual definitions will then be examined in more depth.

Marketing definitions

Each of the definitions chosen below highlights a particular facet of the marketing dynamic. Viewed together they reveal the broad scope of marketing.

“Marketing is the management process responsible for identifying, anticipating and satisfying customer requirements profitably.” – Chartered Institute of Marketing (CIM) UK

“Marketing is the human activity directed at satisfying needs and wants through an exchange process.” – Kotler (1980)

“Marketing is the social and managerial process by which individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating and exchanging products and value with others.” – Kotler (1991)

“Marketing is creating, communicating and delivering value to a target market profitably.” – Kotler (2008)

Collectively these definitions summarize the fundamental elements of marketing as:

•An understanding of customer requirements

•The ability to create, communicate and deliver value

•A social process

•An exchange process

•A managerial and business process

While the fundamentals of marketing may be similar for any industry, the exact nature of their application will differ from one sector to another. In the following pages we will see how each of these elements of marketing can be applied in the context of fashion, and, in particular, how they relate to the connection between the consumer and their clothing.

“Marketing should be an ethos (rather than a department) that pervades every facet of a business.”

Martin Butler

An understanding of customer requirements

The definition from the Chartered Institute of Marketing draws attention to the significance of identifying and anticipating the needs of customers. Naturally this is an important first step in being able to design, produce and deliver merchandise that satisfies or indeed exceeds consumer desires, requirements or expectations.

An underlying concept of marketing is to produce what people want to buy, not just what a fashion designer wants to design or fancies making. It is important to research consumers in some detail, identifying who they are and what they might want. While it is true that many professionals within the fashion industry do have an intuitive understanding of their customers, this in itself does not eliminate the need for research. Predicting future fashion and market trends and working to anticipate what consumers might want is a significant issue for the fashion and apparel industry. Information gathered from market research, retail analysis and trend forecasting is used with the aim of determining the trends, styles, colours or technologies most likely to appeal to customers in the coming seasons.

Some high-street fashion retailers can go from design to delivery in a matter of weeks, but the reality is that many apparel and manufacturing businesses start their initial research and design developments months in advance of a season or product launch; adidas, for example, can take 12–18 months to develop and produce a new product. This lengthy process time, also known as the lead-time, is one of the reasons why anticipating the future is so crucial. Marketing research, forecasting and consumer research will be explained in more depth in Chapters 3 and 4.

Communicating value

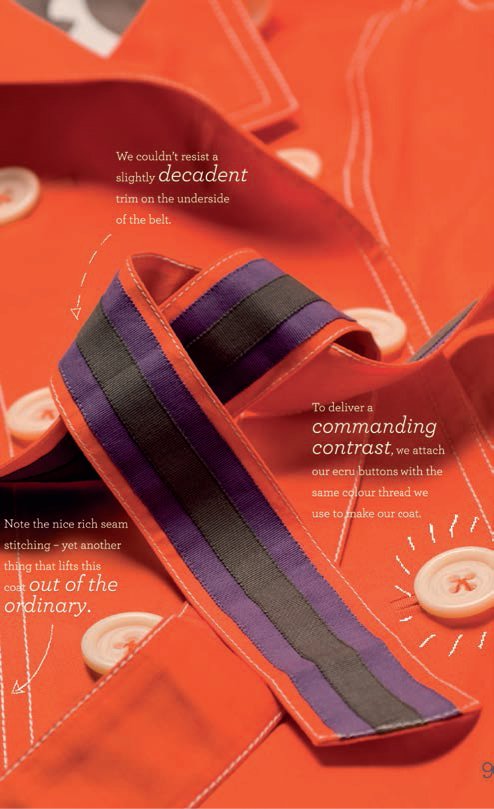

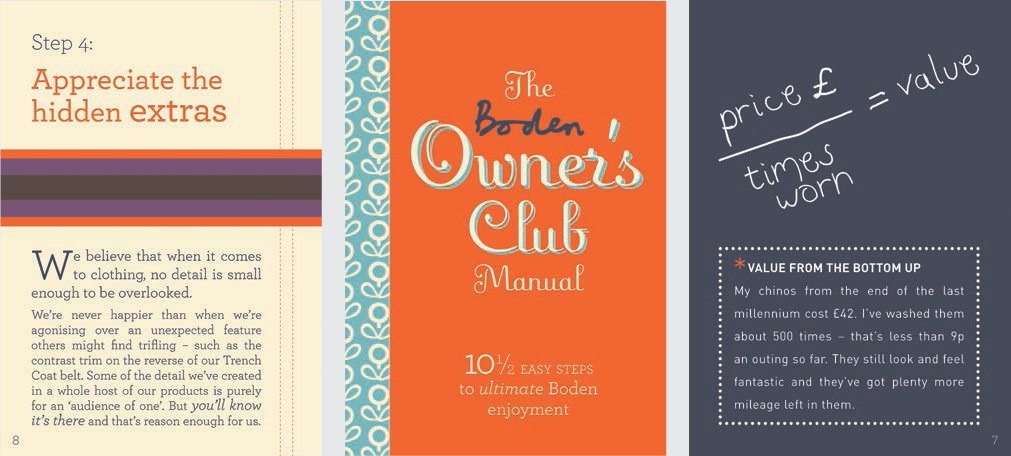

Boden Owner’s Club Manual

Boden is a British mail order and online clothing brand selling to over a million customers in the UK, Europe and the United States. Boden produce colourful, quirky and distinctive womenswear and menswear collections and Mini Boden, a line for children and babies. Inspired by the high standards of US mail order companies, Johnnie Boden started his pioneering upmarket catalogue in the UK in 1991. The Boden website was launched in 1999; now approximately 62 per cent of UK sales and 72 per cent of US sales are taken over the Internet. The Boden brand has been built up so successfully because it offers fairpriced, well-made clothing with a colourful sense of fun and style, delivered directly to the customer’s home. When Johnnie Boden launched the catalogue this was a novel idea. The Boden catalogue and website are used not only to sell the product but also to communicate the Boden lifestyle and brand ethos. The Spring/Summer 2009 catalogue included an insert entitled, The Boden Owner’s Club Manual. The small booklet is jam-packed with information on the details and quality of garment design and the value of the Boden product.

The designers behind the Boden brand believe design details make a difference, so The Boden Owner’s Club Manual is used to highlight the hidden extras that make a Boden trenchcoat so special.

Johnnie Boden uses the cost-per-wear principle to calculate the true value of a pair of Boden chinos. By dividing the retail price by the number of times the trousers have been worn over the years, it is possible to determine their value per wear. The message is that although the chinos might not be the cheapest on the market, they are good quality and will stand the test of time.

Creating, communicating and delivering value

Successful business relies on a strong and effective interrelationship between the activities of creating, communicating and delivering. If one of these aspects fails, it will affect the efficacy of the total result. It is no good creating or advertising wonderful products if they are not delivered. Similarly if products do not match the quality levels expected by customers, or service is not up to standard, then value will not have been delivered.

So what exactly is value? Value does not just refer to low price or what might be termed ‘good value’. In this instance it is used to express a much larger concept and refers to the range of potential issues that customers might value, care about or connect with emotionally. Value may be contained within the product offering – the actual fashion range or collection – but it can also relate to the inherent value or status of a brand. Value is also linked to the overall service a company might provide and to customer experience and satisfaction. The concept of value works both up and down the supply chain; whatever is delivered must not only be of value to consumers but must also create profit and value for the business as well.

Remarkable marketing

“Remarkable marketing is the art of building things worth noticing right into your product or service. Not slapping on marketing as a last-minute add-on, but understanding that if your offering itself isn’t remarkable, it’s invisible.” Seth Godin

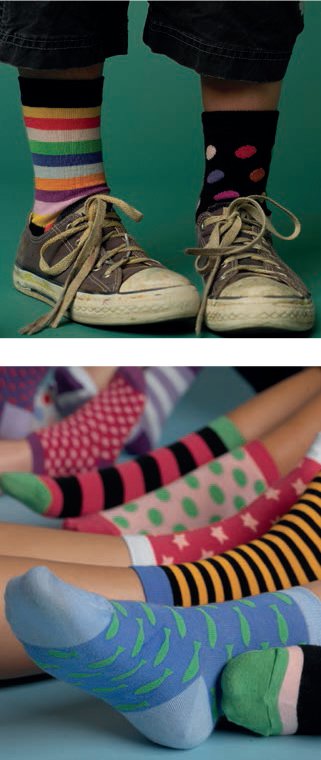

The company LittleMissMatched was founded in the US by three entrepreneurs who recognized a great marketing opportunity – how to solve the age-old problem of the disappearing sock.

“Why do we have to wear socks that match?” the entrepreneurial friends pondered. “Why not start a company that sells socks that don’t match, why not sell them in odd numbers so even if the dryer eats one, it doesn’t matter.”

LittleMissMatched only ever sells socks in odd numbers, three in a pair! Now that is remarkable. And if you get three odd socks that co-ordinate in fun and colourful ways then in essence you get three combinations per pair instead of just one. Revolutionary! Not just boring socks but a crazy way to express yourself and be creative. With a core philosophy of ‘nothing matches but anything goes’, the kooky founders of Miss Matched Inc. thought they had created tweenie sock heaven. They saw their market as girls from four years to teens, but to their surprise the idea caught the imagination of a much wider audience. Now LittleMissMatched is a full lifestyle brand with a range of products for children and adults, including colourful and mismatched gloves and hats, sleepwear, flip flops, bedding, stationery, gifts and hair accessories.

LittleMissmatched has a unique take on marketing. They offer three socks in a pair; while each of the socks co-ordinates with the others in the set, none of them are a complete match. This novel approach solves the problem of ‘the missing sock’.

“Buzzmarketing captures the attention of consumers and the media to the point where talking about your brand or company becomes entertaining, fascinating and newsworthy.”

Mark Hughes

Marketing as a social process

Marketing is a social process where individuals or groups can create and exchange products or information with each other. Fashion has a unique ability to be used as a vehicle for social connection and communication. Individuals often choose to dress in a specific and recognizable style so that they can express their ideas visually and signal membership to a likeminded group, joining what is known as a style tribe. This is a term for a collection of people who dress in a common distinctive style. They may not actually know each other directly but might share similar values and cultural attitudes; by adopting a specific mode of dress, tribe members can shape their identity and gain a sense of belonging.

Style tribes – Exactitudes

Exactitudes (a contraction of exact and attitude), is a project by Rotterdam-based photographer Ari Versluis and stylist Ellie Uyttenbroek. They started working together in 1994 to systematically document the conspicuous dress codes of numerous fashion style tribes around the globe. Selected individuals are photographed standing in an identical pose in a studio setting. The resulting photographs are placed in a grid framework that serves to amplify the striking similarities of each member of the style tribe.

The Exactitudes project illustrates clearly the subliminal influence and pull of a style tribe. The people photographed by Versluis and Uyttenbroek were spotted in the street and had no personal knowledge of the others photographed in their tribe. Although only 12 individuals appear in each tribal collective, responses to the work via blogs indicate that many people who viewed the photographs were able to identify themselves in one of the featured tribes.

We frequently purchase clothes either consciously or subconsciously based on what peers, friends, colleagues or celebrities are wearing. When consumers promote products or pass on style ideas to each other it is known as peer marketing. In many cases this can prove to be a far more powerful marketing tool than advertising or promotion controlled directly by a company. When a marketing message spreads rapidly from person to person it is known as viral marketing. The rise of web-based communication and proliferation of blogs, social networking and sites such as YouTube has been instrumental in the growth of this new marketing medium. Viral marketing utilizes the connectivity amongst individuals to capture attention and create a buzz. Forward-thinking fashion companies such as Levi’s and Louis Vuitton are already integrating viral marketing into their promotional strategies.

Exactitudes, a project by Rotterdam-based photographer Ari Versuluis and stylist Ellie Uyttenbroek documents the dress of fashion tribes from around the world.

Pin-ups – London 2008 Girls inspired by 1940s and 1950s pin-up style. Pencil skirts and blouses with cinched-in waists accentuate the figure. Retro-styled hair is adorned with accessories or hats.

Yupster boys – New York 2006 Yupster = yuppie + hippie. Grown-ups that don’t grow up, this tribe of urban creative professional hipsters came of age during the first wave of indie rock and hip hop. Yupster uniform: T-shirt that communicates values or affiliations, zippered hoodie and all-important cross-body bag.

Geeks – London 2008 Skinny boys in V-necks and specs display their fashion geek credentials.

Charitas – Rotterdam 2007 Power ladies dressed to impress in suits or skirts and structured jackets; handbags at the ready, these women mean business.

Exchanging products and value with others

Marketing is an exchange process. The commodities for exchange are the goods and services and the currency is of course money. However there are other commodities of value to bear in mind, such as ideas, information, connectivity and emotion. Viewed creatively, the exchange process can be seen as a trade system with exciting potential to generate a diversity of assets for both consumers and businesses. A business model that incorporates this wider view is co-creation. This is when a company creates its products or services in co-operation with consumers. Crowdsourcing is a type of co-creation where tasks such as design, which would normally be carried out internally by company employees, are outsourced to the public, thus allowing the larger collective or ‘crowd’ to get involved. The Internet has been a pivotal instrument in the development of co-creational projects. Its potential and connective power offer opportunity to “tap into the collective experiences, skills and ingenuity of hundreds of millions of consumers around the world” (www.trendwatching.com). Within the apparel sector, there is an increasing number of casual clothing companies building businesses around the concept of co-creation. They understand and connect with a particular group of creative, technologically competent consumers, happy to express themselves and share ideas online. This consumer cluster, termed Generation C by analysts at trendwatching.com (the C stands for content), is not related by age but by an attitude to sharing creative content via the Internet. The benefit of crowdsourcing is that it democratizes the process of design, shifting emphasis from manufacturers towards consumers, or users as they can also be termed. This ‘user-centred innovation’ has advantages over manufacturer-centred innovation in that users can create exactly what they want rather than relying on manufacturers to do it for them. Crowdsourcing allows value to be created jointly by a company and its users. It opens up the possibilities for exchange and brings diversity and new ideas into a company. Although users may offer ideas for free, they are usually rewarded with a prize, small fee or sometimes a percentage of sales if their design is chosen. The benefit of crowdsourcing is that it allows a company to communicate with its consumer base, gain knowledge of their needs and preferences and reduce risk by producing product or designs that consumers want.

Consumers get involved

Threadless

Threadless was one of the first clothing companies to place crowdsourcing at the heart of its business model. Launched in 2000, the Chicago-based T-shirt company opened up the design process to any creative individual willing to submit designs suitable for printing on the T-shirts. The concept is managed as an online competition. Each week design submissions are posted on the website; the six T-shirts receiving the highest number of votes from the online community are put into production and sold via the online store. Winning designers receive a prize worth $1,000. This system of crowdsourcing is effective because users are motivated by the possibility of winning and the opportunity to have their work available for sale, while Threadless minimizes risk by only manufacturing the designs chosen by their customers. Encouraged by the popularity of Threadless and the success of crowdsourcing, new casual apparel companies, such as Yerzies and nvohk, are adopting and developing this co-creation business model.

Run Rhino T-shirt from Threadless.

A managerial and business process

Marketing must be managed as an integrated function of business and the ultimate aim is not only to satisfy customers but also to ensure a profitable result. As the Chartered Institute of Marketing’s definition states:

“…the management process responsible for identifying, anticipating and satisfying customer requirements profitably.”

Now let’s examine the key strategic tools available to the marketer. The first of these is the marketing mix.

“Marketing is still an art, and the marketing manager, as head chef, must creatively marshal all his marketing activities to advance the short- and long-term interests of his firm.”

Neil H. Borden

The marketing mix provides a framework that can be used to manage marketing and incorporate it within a business context. The concept of the marketing mix is that several strategic ingredients need to be considered and blended effectively to achieve the marketing and strategic goals of a company. The principles that underpin the marketing mix were first shaped in the US during the 1940s and 1950s. The term was originally coined in response to the idea that marketing managers were considered as “mixers of ingredients”. Neil H. Borden, Professor of Advertising at Harvard Business School, originally listed 12 marketing variables, but in the 1960s, E. Jerome McCarthy rationalized these into four simpler variables – product, price, place and promotion – known as the 4 Ps of marketing.

The marketing mix can be thought of in a similar way to a recipe where the four ingredients of product, price, place and promotion can be blended in varying proportions giving emphasis to whichever aspect is most appropriate to the company, brand or product in question.

The mix employed will be unique to each company or situation, so there is no correct formula. Fundamentally it comes down to ensuring that the product is right for the specified market, that it is priced correctly, that the balance of merchandise is correct, that it is in the right place at the right time and that customers are aware of the offer or service through appropriately targeted promotions. Whatever the market level, an effective marketing mix will need to weigh up a company’s overall objectives while also taking into account any changes and challenges operating in the market at any given time.

Product

For apparel, ‘product’ relates to product design, style, fit, sizing, quality, fashion level as well as performance and function. In the fashion and textile industry, product is rarely a singular item. Commonly it will be a complex range or integrated collection of product. Designers are generally required to construct well-balanced collections or wholesale or retail ranges that include a variety of different product categories offered at appropriate price points for specific target markets. When taking a strategic marketing approach to product, some useful questions to consider are:

•Are the products suitable for the specified market?

•Do the products meet the tangible needs of consumers?

•How will the products satisfy the intangible desires or aspirations of customers?

•Does the total product offer or range address the variety of needs relating to the target customers?

•Is the balance of the range or collection correct? Does it have enough choice and variety within it?

Product attributes and benefits

Product attributes refer to the features, functions and uses of a product. Product benefits relate to how a product’s attributes or features might benefit the consumer. At the most basic level, clothing has core attributes, which offer protection, and safeguard against exposure and nudity. At the next level there are the tangible attributes, integrated into the design, manufacture and function of the garment. These are intrinsic to the product itself and offer concrete and physical benefits to the consumer. So a raincoat made from a water-repellent fabric will have the intrinsic attribute of being waterproof and have the benefit of keeping a wearer dry. Such a garment may be presented in-store with accompanying marketing material informing consumers about the specific attributes and benefits of the design or waterproof material. An item of clothing can also have what are known as intangible attributes. These are more abstract in nature and connect to the ideals, perceptions and desires of the consumer. These intangibles are extremely important for fashion as consumers do not really buy a product but a set of expectations and interpretations, each person perceiving a product’s combination of attributes and benefits according to their own particular needs and viewpoint.

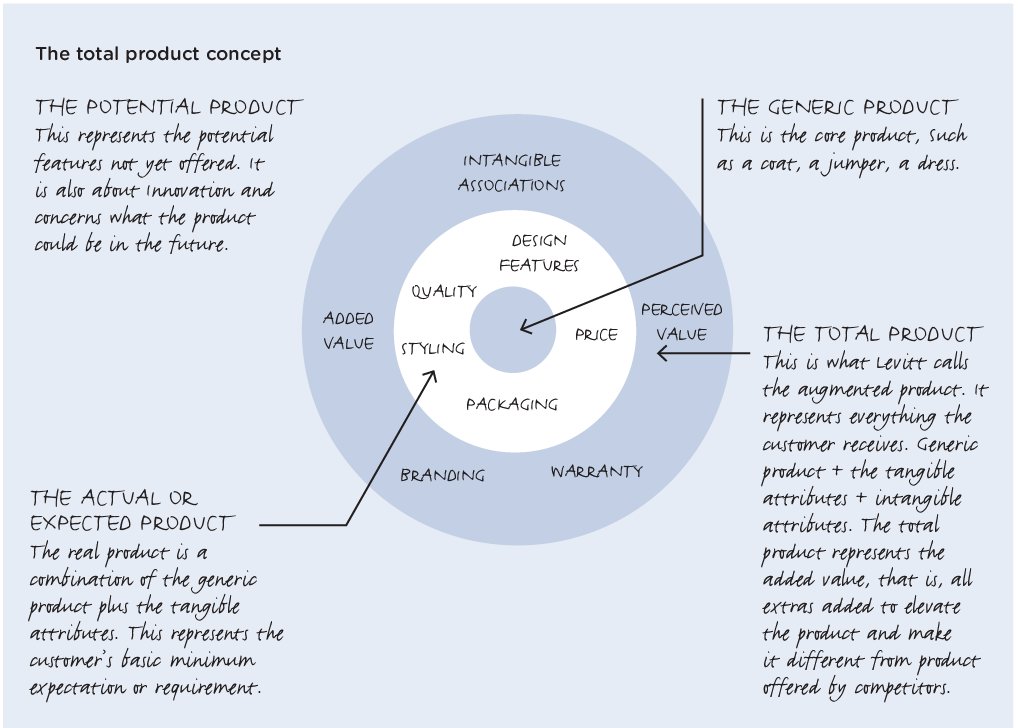

The total product concept

The example of the waterproof coat illustrates what Theodore Levitt called the augmented product or the total product concept. Levitt’s model describes four different levels to a product.

•The generic or core product

•The actual or expected product

•The total or augmented product

•The potential product

The Regatta women’s jacket (left) and men’s jacket (right) have several important functional product attributes: made from Isotex 1000 XPT, an extreme performance fabric, the jackets are waterproof, breathable and windproof. The jackets also incorporate technical and functional design details such as taped seams, a detachable hood, a centre front zip with storm flap and a map pocket.

Synthesizing the practical with the emotional

A waterproof coat

A waterproof coat or jacket is a good example of a garment that can be designed with many practical features and tangible attributes. A coat made of a fully waterproof material has the obvious benefit of keeping the wearer dry in the rain. For someone who wanted a coat to protect them during outdoor or country pursuits, a loose-cut practical waxed jacket might provide the benefits they require. If in addition it had a detachable inner lining, then the benefits of flexibility and keeping warm could be added to the list. At an emotional level, a consumer might choose a waxed Barbour country jacket, not only because of the durability, warmth and protection it offered, but because emotionally, the wearer connected to the heritage and values of the Barbour brand. The wearer might feel ‘earthy’ or ‘connected to the land’ when they wore it. They may appreciate quality and tradition and practicality. A different consumer, on the other hand, who wanted to feel ‘active and alive’ or ‘daring and adventurous’ might purchase a lightweight waterproof with high-performance features, even if they wore it in an urban setting or to go to the shops. The wonderful benefits of a high-performance or practical country jacket are likely to be of no interest to someone who wanted to feel alluring, fashionable and chic while they kept dry. For this consumer the silhouette or shape of the coat may be of major importance, along with the fashion status of a brand name. They may desire a designer label raincoat with a belt so that they can cinch in their waist and show off their figure to best advantage.

Each of the garments described provide the functional benefits necessary for specific uses or activities. But clothing provides more than the merely functional. The clue to understanding this is to view attributes from the consumer perspective and try and determine what consumers might feel, desire or aspire to when they purchase fashion product. Each attribute will generate a set of emotional meanings that augment the tangible or physical benefits. This is why fashion in general and branding in particular can be so powerful – they have a unique ability to confer the intangible and create a short-cut straight to the emotional.

American actress Maggie Gyllenhaal looks sophisticated and urban in a belted trenchcoat.

French actress Fanny Ardent makes a simple, classic raincoat look alluring and desirable.

If we consider a waterproof coat such as a classic trench, then at the most basic level the product is a coat. At the next level it is a waterproof coat with specific design features and styling details offered at a particular quality and price. The next tier up is the total or augmented product. This represents everything that the customer receives when they purchase the raincoat, including all elements that contribute to added value, intangible benefits, branding and emotional benefits. The total augmented product relates to everything that is currently being offered, but there is another highly significant layer to consider and that is the potential product. This is everything that could be offered or might be offered in the future. For fashion the future happens very fast and designers spend most of their time working on potential product. They must innovate and update, moving product design forward each season with new design ideas, fabrics and technologies. The concept of potential product is therefore of vital importance.

Levitt’s model highlights another important point. “Consumers don’t buy products or product attributes. They purchase benefits and emotional meaning.” This means that potential product must also be about identifying innovative ways to deliver extra value and benefits to the customer.

In this context price means manufacturing costs, wholesale and retail prices, discounted prices and of course margin and profit. For marketing purposes it is possible to view pricing from two perspectives; one is from the point of view of cost, what an item actually costs either to produce or for a buyer to purchase. It considers tangible expenditure so that a cost price can be calculated. The second standpoint, selling price, looks at the situation from the customer or end-consumer’s perspective. It considers what might be a realistic selling price and factors in issues such affordability and perceived value. Perceived value reflects the apparent worth of a product; this may not directly relate to the actual cost of production or wholesale purchase price. An understanding of customers’ perceptions of value is therefore very important, as is knowledge of competitor pricing within the marketplace.

The display in the John Varvatos Malibu store features a range of products including jeans, shoes and accessories. The product mix offers customers an opportunity to buy into the Varvatos collection at a variety of price points.

Research is an essential element in understanding pricing both from a customer or end-consumer perspective and in terms of what the competition is up to. And of course, prices change frequently so research helps gain insight into:

•How customers perceive price

•What customers consider good value

•How much customers are willing to pay for specific products

•What customers will pay more for

•How much competitors are charging

It is rarely only one item that will need to be priced. A well-balanced selection of product will need to be constructed and a coherent pricing strategy devised not only for each individual item but for the entire offering.

Price architecture

A pricing structure will have to be planned or built up from the lowest cost items right up to the most expensive. This is known as the price architecture. Within the price architecture there should be products offered at:

•Introductory or low price points

•Medium prices

•High price points

It is customary to create a price band for each of these tiers. For example, a high-street retailer might set their lowest price band at £15–49, the mid-price band at £50–99 and the top band at £100–200.

Price architecture is dependent on the type of market, the market level and the product concerned. The proportion of styles and the stock volumes within each of the tiers is adjusted so that the business can satisfy the greatest number of customers and generate the highest potential sales margin and profit.

Each retail price band can then be further subdivided with specific price points. The top price band might, for example, have only four price points, £115, £125, £150 and £200. The lowest pricing tier might have something in the region of eight to 12 separate price points. Skilful setting of price points and consideration of the number of styles offered at each price within a pricing band are essential elements to the planning of a balanced range. It may not be possible to achieve the desired profit margin on every style but judicious flexing of prices should help to increase margin on enough product so that a workable margin is achieved overall.

Pricing calculations

The following examples outline some quick pricing calculations that can be used as a rough guide for understanding pricing parameters. The most useful overall tool is to monitor retail prices on a constant basis and take note of actual prices within the market.

Cost-plus calculation

The cost-plus pricing formula can be used as a guideline to determine the cost of producing an item and calculate the minimum price that must be charged to recoup the original financial investment. The total cost of producing the product is derived from the fixed and variable costs. Fixed costs, such as rent, salaries and insurance, remain the same whatever amount of product is produced or sold. Variable costs are expenses that vary in direct proportion to the quantity of garments manufactured and include the cost of raw materials, packaging, labour and shipping charges. The minimum price that should be charged for the product is calculated by dividing the total costs by the number of units produced.

MINIMUM PRICE = (Fixed costs + variable costs) / number of units

If a manufacturer produces 2,000 units of an item with fixed costs of £10,000 and variable costs of £5,000 then the cost per unit will be £7.50.

10,000 + 5,000 / 2,000 = 7.50

If the manufacturer were to receive £7.50 for each of the 2,000 units, then they would get their money back but would not make any profit. In order to achieve a profit, a mark-up percentage must be added. To achieve a mark-up of 40 per cent, the selling price per unit will be £10.50.

MINIMUM PRICE = (Fixed costs + variable costs) x

(1 + mark-up percentage) / number of units

(10,000 + 5,000) = 15,000

(1 + 40%) = 1.4

15,000 x 1.4 = 21,000

21,000 / 2,000 units = 10.50

The cost-plus pricing formula is dependent on the actual volume of product sold, so if the manufacturer does not sell all 2,000 units at £10.50, then a profit may not be achieved. If only 1,000 units were sold then the price per unit would need to be raised to £21.00 in order to get a return on the investment.

Mark-up and margin calculation

A retailer wishes to purchase 2,000 units from a manufacturer. The manufacturer opens negotiations at £12.00 per garment. The retail buyer can gauge the potential retail price by multiplying the wholesale price by a mark-up factor. If the buyer calculates a retail price by doubling the cost price, then they will have used a mark-up factor of two. This will achieve a mark-up percentage of 100 per cent and a margin of 50 per cent. Mark-up calculations work on a cost-up basis; that is, they view pricing from cost price and work upwards. Margin calculations look at the picture from the perspective of the selling price.

MARK-UP PERCENTAGE = (Cost price x mark-up factor) – cost price/cost price x 100 (12 x 2) = 24

24 – 12 = 12

12 / 12 = 1

1 x 100 = 100

MARGIN = (Selling price – cost price) / selling price x 100

(24 – 12) = 12

12 / 24 = 0.5

0.5 x 100 = 50

A fashion buyer will monitor retail prices within the market on a regular basis and will have a clear idea of the retail price they wish to sell a particular garment at when they enter into a price negotiation with a manufacturer. If a buyer works with a mark-up factor of 3.5, they will achieve a margin of approximately 70 per cent (excluding taxes).

Looking at the garment and knowing current pricing in the market, the buyer understands that the maximum selling price they can charge for such a garment is £39.99 and that if they buy it in at £12.00 they would have to sell it at £42.00 in order to achieve the correct margin. The buyer therefore negotiates with the manufacturer and an eventual cost price of £11.50 is agreed.

The final margin calculation is set out below.

(39.99 – 11.50) = 28.49

28.49 / 39.99 = 0.71

0.71 x 100 = 71 per cent margin

* Calculations do not contain adjustments for sales tax.

In essence, place is about getting the right product to the right place at the right time and in the right amount. It concerns logistics and the various methods of transporting, storing and distributing merchandise and the means by which a company’s products reach their target customer; termed as ‘route to market’ this relates to distribution and sales channels. The key sales channels by which apparel product reaches the end-consumer are:

•Direct routes such as the Internet or purchasing via telephone.

•Service-orientated channels; in other words a retail store, or what is termed as bricks and mortar retail.

•Catalogues – some companies start by producing a catalogue. They may then expand to open stores or operate a concession within another store. Most printed catalogues now also operate a second channel online.

•Public events such as sports or fashion events, or craft or country fairs.

•Trunk shows for invited customers (see caption).

Routes to market for the fashion trade can be via the following channels:

•Trade fairs

•Agent’s showroom

•Company-owned showrooms either at head office or located in key global locations

•Internet

•Via a sales team

•Direct from manufacturer

•Via an agent

•Trunk shows

Stella McCartney talking to customers at her Autumn 2009 trunk show at the Chicago store of Barneys New York. A trunk show is a special preview event where a designer will show off their latest collection to a select group of invited guests and customers. Usually guests will be able to purchase or order items during the event. Trunk shows are commonly held in a boutique or in the designer section of a department store and are excellent for marketing as they allow a designer to reach an audience that would not normally attend catwalk shows. They also provide an excellent opportunity for the designer and retailers to obtain vital pre-season information on which styles will be successful.

Variations might exist between retail stores in different national or international locations. Customer requirements or purchasing patterns are likely to differ, so a store in Germany might carry a different selection of styles and colours compared to one in southern Spain. Equally, the size range of garments may need to be adjusted to take into account variations in physique prevalent within different cultures. The merchandise offer will also be determined by the dimensions and layout of the retail space. Not every location will be able to display the same volume of stock, so the selection will need to be modified to suit the practicalities of the store.

Trade fairs and exhibitions

Timberland takes a stand

Industry trade fairs provide an important opportunity for companies to showcase their new product ranges and sell to retail buyers from around the globe. The advantage of a trade fair or exhibition is that buyers can view and compare a variety of brands all showing at the same event. Shows will be sector specific; Première Vision in Paris for fabric or Pitti Filati in Florence for yarn spinners, CPD in Düsseldorf for womenswear and accessories, or Bread & Butter in Berlin for street and urban wear, for example. Thousands of trade buyers typically visit these fairs; 33,500 visitors from over 59 countries attended the Igedo fashion fairs in February 2008. Exhibiting companies invest heavily in creating show stands that represent their brand and their products to best advantage.

The Timberland trade-show stand for its Outdoor Performance range is created using re-purposed industrial objects and natural recycled materials. Shipping containers have been re-deployed to create selling booths where clients can view the Timberland product range and place orders.

The innovative trade-show stand, designed by Michigan-based design firm JGA, reflects Timberland’s commitment to environmental sustainability. The highly distinctive design is constructed from 98 per cent ‘earth conscious’ materials (53 per cent re-used, 18 per cent renewable, 27 per cent recycled), and 88 per cent of the stand can be recycled at the end of its use.

Timberland trade-show stand for their Outdoor Performance range. Graphics set the mood in the central ‘meet and greet’ space where trade buyers are welcomed onto the stand by Timberland sales representatives to view the product ranges and place orders.

JGA also designed the stand for the Timberland Pro series. The highly flexible build is designed to accommodate different trade-show footprints. Sales rooms display the Pro Series products and provide worktable seating for 8–10 people.

Promotion is about communicating with customers and includes all the tools available for marketing, communicating and promoting a company and its products and services. The combination of promotional activities, such as advertising, sales promotion, public relations, personal selling or sponsorship, is known as the promotional mix. The idea behind this is similar to the marketing mix and relates to the mixture of promotional tools that can be employed to achieve a company’s promotional objectives. Some of the most recognized promotional vehicles for fashion are the advertising in high-profile fashion magazines like Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar, Grazia or Marie Claire; catwalk shows that gain extensive media and public interest; and the PR and razzamatazz that surrounds celebrities and their endorsement of designer fashion. There are, however, many more innovative and creative ways to promote fashion. One way for a retailer or fashion wholesaler to promote their business and provide something extra for customers is to produce an in-house magazine or seasonal brochure. Producing a high-quality, multipage publication is a costly and intensive process, so companies that choose to do this usually publish on a biannual basis, timing editions to promote Spring and Autumn collections. The style and content of the publication must reflect both the underlying values of a brand and the attitudes and interests of targeted customers. Magazines and brochures are also a great vehicle for communicating essential information such as contact details for head office or customer services and locations and addresses of stores. Further promotional ideas will be discussed in more depth in Chapter 6.

Massey & Rogers produce beautiful printed items such as bags, brooches, tea towels and greetings cards. They take great care with presentation – their set of three bird-print tea towels are packaged with cotton tape and branded with a simple swing ticket.

The marketing mix today

The drawback of the marketing mix is that it tends to focus on the internal needs of the company rather than the ever-changing requirements of customers. The traditional 4P marketing mix was primarily developed during the rise of mass consumerism to market the tangible benefits of product – the limelight falls on issues surrounding producing, pricing and promoting product. Newer thinking believes the consumer should be at the heart of the matter. An expanded 7P version of the marketing mix has been developed to address this change in emphasis; it includes three further criteria, physical evidence, process and people. It can be a common mistake to consider fashion as a product-based industry, however – it should really be viewed as service- or people-based. Fashion retail concerns the experience of shopping, so service which incorporates the extra Ps could be viewed as a marketing tool of the highest importance.

Physical evidence

Consumers increasingly demand more in terms of value, experience or extra service, and as the ability of fashion retailers to match each other’s product offer rises, so the criterion of physical evidence plays an ever more important role in differentiating one retailer from another. Physical evidence relates to issues surrounding packaging, brochures, business cards, website design and usage, carrier bags, staff uniforms, in-store décor, ambience, facilities, retail fixtures, store windows and signage.

The fashion experience is about so much more than just the clothes or accessories themselves, it’s all the little extras that make a difference. The label in the garment embroidered with the designer name, the well-designed and beautifully crafted swing ticket, the carrier bag so special that it is kept as a treasured souvenir, or stunning windows and store displays that capture the imagination and make a shopping trip feel thrilling. All these extras are vitally important aspects of the marketing mix. They are persuasive factors that add value, enhance customer perception of a retailer or fashion brand and elevate one company above another in the hearts and minds of consumers.

Creating a world of beauty and artistry

Prey UK

Prey is a unique boutique retailer situated in the historic city of Bath in the UK. The shop has been described as an Aladdin’s cave of beautiful objects; it is the ultimate micro department store, selling a diverse range of fashion, jewellery, accessories, fragrance, gifts and homeware. The whole ethos behind the Prey world is to delight customers and provide an ambience of beauty and artistry. This philosophy is apparent throughout the store, but one of the most delightful features is the beautiful packaging and exquisite illustrated carrier bag. The Prey bags are a treasure in themselves, far too gorgeous to ever throw away and a tempting inducement to buy into the Prey world and purchase from the boutique.

The Prey UK carrier bag is beautifully designed and crafted. The intriguing illustration artfully tells a story. The woman appears to be walking a dog but when the bag is reversed it becomes clear that it is a bird of prey.

Creating a Camper Universe

Camper Together with Jaime Hayon

Fashion is becoming increasingly about experience so the design and feel of a retail store is highly important. Many fashion brands employ high-profile architects or innovative designers to help them create stylish, exciting and dramatic retail spaces. Camper is a modern footwear brand resonating with fun, imagination and creativity. On a practical level, Camper makes shoes for wearing and walking but at the same time they believe they make shoes for ‘imagining’. The Majorcan company has a unique approach and philosophy that enables it to integrate several opposing and contradictory ideas and their stores provide a window through which they can exhibit their shoes and communicate their unique viewpoint to the world. To this end they created the ‘together’ concept, collaborating with Jaime Hayon. The distinctive retail environments conceived by this young Spanish artist bring the spirit of imagining and Camper Universe to life. The store-galleries located in Barcelona, London, Paris, Palma de Mallorca and Madrid showcase the designer’s idiosyncratic modern take on traditional forms and shapes. Hayon’s quirky, baroque touches, reflective surfaces and gold flourishes meld with the Camper philosophy to establish an intriguing contemporary setting in which to display the shoes and delight shoppers.

Jaime Hayon’s designs for the Camper store in Cherche Midi, Paris.

Process describes the customer’s experience of the brand or service from first point of contact onwards. It considers the experiences and procedures they may have to go through in order to make a purchase and includes issues such as information flow, ordering, payment, delivery, service and return of products. In the modern marketing climate, with increased reliance on marketing and selling via the internet, process is a potent tool, especially for businesses wishing to build customer loyalty and ensure customer retention. Whatever the exact nature of a business, it is always worthwhile to take time to review the process customers go through when they make a purchase or use a website, to see the steps from the customer perspective rather than just what might be efficient for the company.

A customer purchasing a wedding dress will go through a series of steps from first consideration to final purchase and ultimately wearing the dress on her wedding day. The first step may be looking at wedding magazines and doing online research to find suitable ideas, designers or retailers. Next, there could be telephone conversations or emails to gather further information or book an appointment to view a collection, sessions to select fabric and develop a personal design, followed by several fittings, the final fitting, taking delivery of the dress and then the wedding itself. Each step in the process is a moment where the consumer and company providing the service interact. Every interaction provides an opportunity for the business to differentiate itself from competitors, create value and ensure a positive experience for the customer.

Process expands the marketing viewpoint beyond the product itself and recognizes the value of smooth interactions and good service. In combination with great product, process builds trust, loyalty and repeat custom. Hopefully, a wedding dress will be a one-off, once-in-a-lifetime purchase, so positive customer experience is less likely to result in a repeat purchase but it will certainly contribute towards an enhanced reputation and customer recommendations. Conversely, customer irritation with any part of the process could lead to a lost sale, deterioration in trust and erosion of customer goodwill or loyalty. In the case of a wedding dress there may be other people to please along the way – the bride’s mother or a best friend or bridesmaid. Process may appear to relate to systems and organization but in reality it is all about people and their potential.

Think OUTSIDE IN! In other words imagine being the customer. What kind of service do they require? How can you improve the processes they go through to purchase your products? How can you make the process smoother, more exciting, more engaging, more efficient and memorable for the right reasons?

Now think INSIDE OUT. Have you made internal processes smooth and efficient? Will internal processes support customer experience – even if employees don’t deal directly with customers their internal or interdepartmental processes may cause glitches that indirectly affect results.

People

‘People’ in this instance does not just refer to consumers, it has much wider implications and opens up the scope to include all those who add value to the development and delivery of a product or service. People can therefore include employees, partners, stakeholders, collaborators, producers and suppliers. It can be a trap to consider fashion as only a product-based industry; it is just as important to view it as retail and a service experience. People add value along the entire length of the supply chain and are, of course, integral to the service provided by any company. People should therefore be considered as a vital part of the marketing mix.

Valuing people

Earnest Sewn jeans

Earnest Sewn is an American denim brand designed by Scott Morrison in Los Angeles. The name is central to the brand concept – literally translating as ‘product sewn in earnest’. The denim label is underpinned by fundamental core values of quality, integrity and authenticity and the Japanese concept of Wabi-Sabi, an aesthetic system honouring the traditional beauty of imperfection. Traditional Wabi-Sabi products are produced by hand and weathered by time. For these values to have any significant worth or real meaning they must be utilized by Earnest Sewn and be embedded into the company’s design and manufacturing processes and integrated into the marketing strategy. In order to achieve this Earnest Sewn has abandoned the normal assembly line approach to production. Wherever possible one person carries out the majority of the sewing for each garment; in this way the company is able to manifest the ideals by which it stands. Each maker is able to focus on an individual pair of jeans, increasing the opportunity for subtle inconsistencies, imperfection and the irregularity of things made by hand. Typically, three people oversee and monitor the jeans’ progress from design through to shipping. When the jeans are complete, those involved in their production put their name to their work by signing the pocket lining. This validates the authenticity of the jeans and signals the integrity of the manufacture. The signed pocket lining communicates that the jeans are indeed, ‘product sewn in earnest’.

Earnest Sewn jeans are signed by the three people who work on the garment from design through to shipping. One person is responsible for the majority of the sewing on each pair of jeans. This innovative approach changes the dynamic of the manufacture from ‘production line’ to something closer to ‘hand-made’.

Changing the Ps to Cs

The most up-to-date marketing theories, such as relationship marketing, recognize the importance of building long-term relationships between a business and its customers, the aim being to attract loyal customers who will spend consistently over time. A model devised by Professor Robert Lauterborn reframes the marketing mix. By changing the Ps into Cs, Lauterborn shifts the emphasis away from product, price, place and promotion onto the customer.

“Retail is a people business. For sure, customers pay their money for whatever it is that you, the retailer sell to them, but there’s so much more to the relationship than this exchange.”

Martin Butler

The Lauterborn model may not have been created with fashion specifically in mind, but it is possible to consider its implications. What, for example, might it cost consumers in real terms to satisfy their needs or fashion passions? Factors such as time and convenience have to be integrated into the pricing equation. Consumers may be cash rich but time poor, they might have disposable income but not enough time to shop for clothes. For some, shopping is seen as a social or leisure activity, an experience often shared with friends. A morning perusing the high street or mall might be perceived as time well spent, even if very little was actually purchased. Many women and occasionally some men buy clothing and fashion completely spontaneously, having had no original intention to purchase anything that day. Some consumers could be described as fashion addicts. For them, convenience is not an issue; they might be willing to make special trips or even pilgrimages to ensure they fulfil their fashion dreams or requirements. Others may spend hours monitoring an auction on eBay to ensure that they are the ultimate victor in a bidding war for an exclusive fashion item. There are also, of course, customers with limited interest in fashion and little inclination to spend their time trawling the shops, who nevertheless need to buy clothing for themselves or their family members.

Consumer psychology and communication are the unifying principles that tie this new set of criteria together. There is a need to understand the psychological impulses behind consumer fashion choices and recognize sensitivities to time, costs, value and convenience. By viewing marketing from the consumer’s perspective, far more must now be achieved than just delivering the right products at the right price. The way consumers value fashion, style, self-expression and identity should naturally be viewed as part of the marketing equation.

Business processes of marketing

So far we have defined marketing and set out its parameters, explaining that to be effective it should be integrated into the entire fabric of a business. Although strategies and objectives may vary according to the size and goals of the business concerned – a large global corporation, for example, may have a significantly different structure or way of operating compared to a small independent niche company or self-employed fashion designer operating out of a tiny studio – the overall business processes involved in marketing are in fact very similar and can be summarized as:

1.Identifying business opportunity

2.Developing products and services

3.Attracting customers

4.Retaining customers

5.Delivering value

6.Fulfilling orders and business agreements

Each process is intimately linked to the others, so the failure of one has the potential to jeopardize the business as a whole and negatively affect customer perception of the company or brand. In order to be successful a business venture must therefore carry out all these processes effectively. This is where the marketing mix comes into play. It is instrumental in supporting a unified approach to the business and marketing.

The framework of the marketing mix and the overall business and marketing processes can be applied to any business throughout the fashion and textile supply chain. Each interaction along the chain should be viewed as a business relationship; this is why it is important to include the criterion of ‘people’ within the marketing mix. This diagram represents a simplified version of the supply chain but it could be expanded to take into account other businesses, such as agents and distributors.

Marketing strategy

It is an extremely tough challenge for a fashion manufacturer, supplier, designer brand or retailer to appeal equally to all customers or consumers. It makes sense therefore for a business to concentrate its resources and activities and focus on a specific area of the market, fine tuning or ‘positioning’ the brand, product offer and services so that they appeal more directly to a specified and well-defined target audience. This is the fundamental principle underpinning STP (segmentation, targeting and positioning) marketing strategy.

Segmentation and targeting

Market segmentation is a key function of marketing; its purpose is to divide a market into smaller, more focused sectors. The fashion market can be segmented in several ways, for example by product type or market level. There is a market for couture, the luxury designer market, the accessory market and branded sportswear. The process of segmentation can also be used to cluster consumers into groups that share similar characteristics. Consumer segmentation is the research and analysis technique used to define these groups. It categorizes consumers in terms of their age, attitudes, behaviours or by the type of products and services they might need. (This is described in greater depth in Chapter 4). Segmentation is a means to an end, the tool that facilitates the next step in the process; targeting. This is the process of developing products or services specifically aimed to appeal to a particular customer segment. Companies that offer petite ranges, for example, are targeting smaller-sized customers. A fashion brand targeting older female customers might design, cut and size garments in such a way as to flatter the figure of the older woman.

Positioning

Having segmented the market and selected which sector and consumers to target, a company must now position its brand within the market, so that it will appeal directly to the target market. This is an approach taken by the Arcadia Group, the UK’s largest privately owned clothing retailer. The Group operates seven well-known high-street retail brands, each positioned to attract a particular type of fashion consumer. Topshop, one of Arcadia’s most famous brands, targets young girls and women aged 13–25 and positions itself as a brand offering ‘cutting-edge fashion at affordable prices’. Dorothy Perkins (DP) is aimed at a broader range of women aged 25–45. The average DP customer is in her thirties and is a busy mum or working woman; the core value at Dorothy Perkins is ‘value for money’.

Kate Moss appears as a mannequin in the window of Topshop during the launch of her first collection for the retailer. Topshop positions itself as a brand offering cutting-edge fashion at affordable prices; signing Kate Moss was a strategy designed to attract young fashion-conscious customers.

“Positioning is not what you do to a product. Positioning is what you do to the mind of the prospect.”

Ries & Trout

Positioning, however, is a slightly complicated issue, because it is really a matter of perception. It is about the position a brand occupies in the mind of a consumer or potential consumer. Furthermore this position is relative. Positioning is about where a brand or product is perceived to be within the marketplace relative to the other brands or products operating within the same sector. So for example, consumers may feel that a Prada handbag is inherently more desirable than a bag sold by another luxury brand which they might perceive to be more traditional or staid, or they may consider the garments made by one sports brand to be of a higher quality than another, when in reality both use the same factory to manufacture their apparel.

In order to position itself, its brands or its products effectively a business must develop a positioning strategy. The strategy will be dependent on where competitors position themselves and how the business wants its brands or products to compete. So, taking the example of a luxury accessory brand viewed by consumers as more traditional and less cutting-edge than Prada; this brand could decide to strategically position itself close to Prada – to compete head-to-head and try and beat the competitor brand at its own game. If this were the strategy, then the brand would offer similar products or services at comparable prices. It is of course high risk and costly to compete aggressively with a market leader and there may be no real advantage for consumers in having two virtually identical brands. Another option would be to position the brand within the same market but to offer something distinctly different, or provide extra benefits.

When working on a positioning strategy it is helpful to create a positioning map. This can be used to pinpoint the desired position for a brand and give a visual overview of this position relative to that of competitor brands within a market. Given that positioning is actually dependent on the perception of consumers, the company must also attain knowledge of how consumers perceive their brand within the market. Once research has been carried out, a perceptual map can be produced. This is very similar to a positioning map but is based solely upon consumers’ perceptions of the brand rather than where the company wishes to position it. The map will indicate the consumer perceptions of the brand’s current position and identify where shifts are required to align them with the company’s desired position. This pursuit of alignment is called repositioning, the process of redefining the identity of an existing brand or product in order to shift the position it holds in consumers’ minds relative to that of competitors.

The year 2008 heralded the return of the supermodel. In a bid to make their product desirable to a more discerning customer, luxury fashion brands signed up well-known older models like Linda Evangelista who became the face of the Prada Autumn/Winter 2008 campaign.

A positioning or perceptual map plots the relative positions of brands or products. Two key criteria are chosen, one for each axis. Normally, price is the criterion chosen for the horizontal axis. The vertical axis may represent quality or fashionability or speed to market. In this instance fashionability has been chosen.

So to summarize the positioning process:

•Define the market in which the brand or product will compete

•Decide where to position within the market

•Determine whether to compete directly against a competitor or how to differentiate and compete by being different

•Understand how consumers perceive the current position

•Determine if repositioning is necessary

Once a clear position for the brand or product has been established, the next step is to ensure that this position is communicated to consumers. All facets of the brand, its image, products, packaging, retail environment, promotion and advertising will convey this position and it is therefore vital that every aspect is congruent and supports the desired positioning. Positioning and repositioning are costly exercises; the most effective positioning should therefore be long-term and remain consistent. Moving a brand’s position is not a tactic to be carried out repeatedly. The aim is to establish a strong and recognizable position that is consistent over time and to make sure products and brands are clearly different from those offered by competitors. This is the principle of differentiation, closely allied to the concept of positioning it is the next strategic tool to be discussed.

Differentiation is the concept of developing and marketing products or services so that they are different and hopefully superior to those offered by competitors within the same marketplace. It is a fundamental strategic approach that ensures products and services are distinctive and stand out from the crowd.

The ultimate aim of differentiation is to achieve what is known as a competitive advantage. A company achieves an advantage if it is able to provide products or services of greater value to consumers than those offered by competitors. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, value is not just an issue of price. Customers might value premium service or luxury quality or the high status of a particular fashion label and they may indeed be willing to pay more for it. Alternatively it might be street credibility that gives a brand a competitive edge or the fact that a world famous sports team endorses the brand. These extra elements augment the basic product, add value and help achieve competitive advantage.

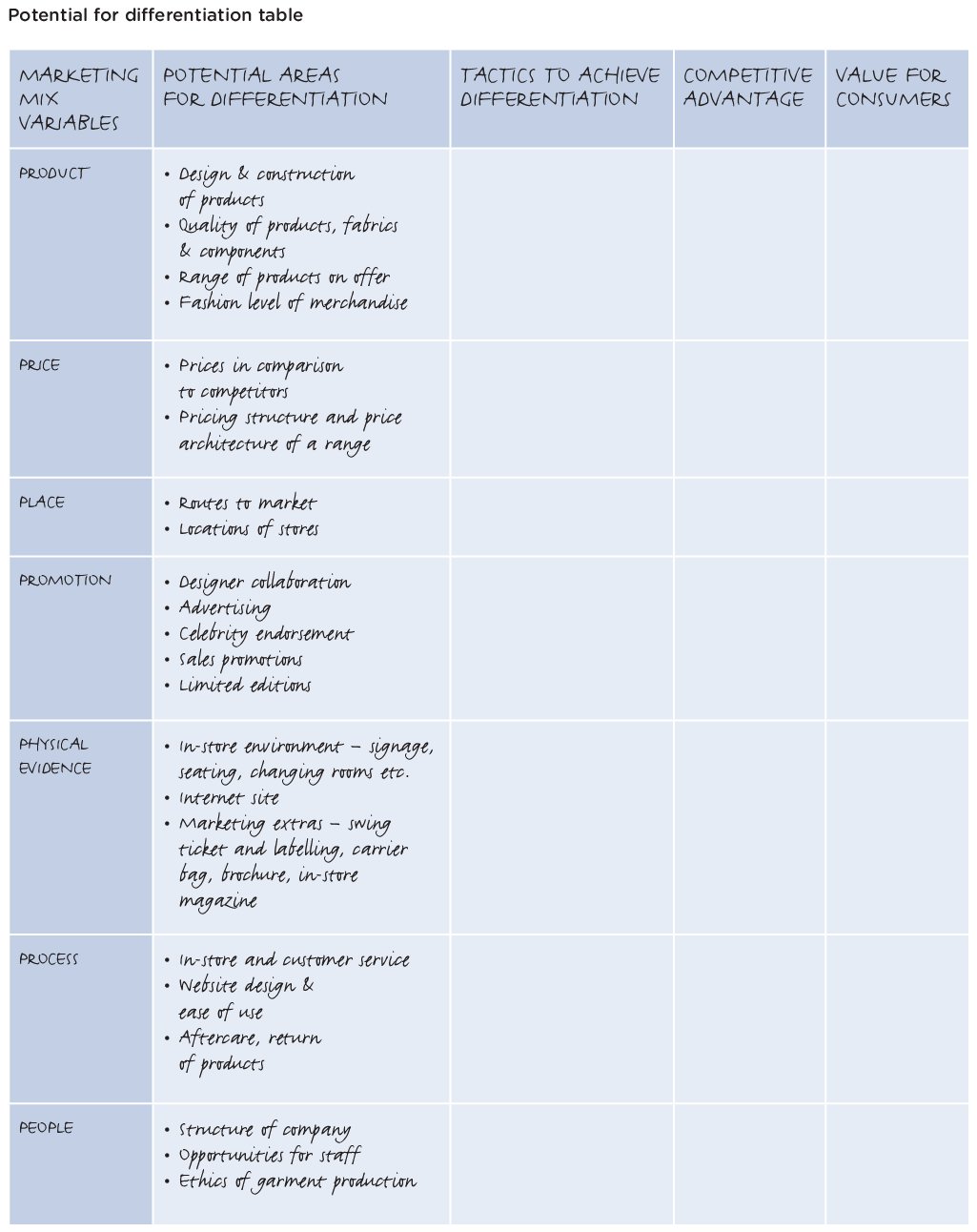

Opportunity to differentiate exists at every stage of the marketing process. Differentiation and competitive advantage can be achieved through design and technology innovation, by strategic management of the supply chain or in the way a brand or product is retailed, distributed or promoted. The Potential for Differentiation table shown opposite uses the 7P marketing mix as a framework for exploring possible areas for differentiation and competitive advantage. Once relevant areas for differentiation have been identified, then practical steps can be planned and strategic actions put into place so as to achieve the desired outcome. The chosen tactics must also contribute towards creating a competitive advantage for the company and, of course, offer clear value and benefit for the consumer.

Competitive advantage

The Potential for Differentiation table should highlight some of the ways a business might differentiate itself and achieve an advantage over competitors. One obvious way to compete in a marketplace is to be the cheapest and gain a cost advantage. In this case the design or quality of products might be comparable but the competitor that offers them at the lowest price might gain the advantage. However this is likely to be a short-lived victory. The problem with this approach is that it soon becomes unsustainable. Competitors will usually reduce prices to match and a vicious cycle of cost reductions will eventually lead to erosion of profits for all concerned. Cost alone no longer provides a strong enough advantage; it needs to be aligned with other beneficial factors such as speed and what is known in the trade as fashionability. In other words, companies that manage to get reasonably priced catwalk-inspired styles or the right trends into the market faster than rivals have not only managed to achieve a cost advantage but also a speed advantage and what could be termed a fashion advantage; this of course is the operating principle behind the concept of fast fashion. Zara, one of the brands owned by the Spanish Inditex Group, has become a famous fashion phenomenon. The international retailer has consistently been able to offer reasonably priced stylish interpretations of catwalk trends at exceptional speed. A tightly controlled production system allows Zara to move swiftly from a design drawing to a finished garment delivered to store in a period of between two to three weeks. The international retailer achieves its speed advantage because the Inditex Group possesses its own manufacturing and distribution capabilities and operates what is termed a vertical supply chain. The company has spent more than 30 years perfecting this highly integrated production and distribution model. It is Zara’s legendary lead-time (the time between placing an order and the stock arriving in-store) that gives it its competitive advantage.

This table is designed as a tool to help identify potential areas by which a company can differentiate itself, and its products and services. The marketing mix should be used as a framework. Some initial ideas for differentiation have been given here as an example. Once relevant areas for potential differentiation have been identified, then specific objectives can be set and tactics devised to achieve each particular aspect of differentiation.

Asos, the UK online fashion retailer, illustrates the next evolutionary development in the competitive platform in fashion retailing. The web-based company, whose name is an acronym of ‘As Seen on Screen’, was established in June 2000. By December of the same year it was voted ‘Best Trendsetter’ by The Sunday Times newspaper. In 2008, the company reported profits of £7.3 million and its rapid growth and ability to weather the early stages of the recession has provided a wake-up call to competitors. Aimed at the ‘fashion forward’ customer between 16–34 years old, Asos has stolen the advantage by bringing must-have fashion ideas straight to the consumer via their computer screen. Asos gains competitive advantage by adding a new dimension to the cost, speed and fashionability dynamic, namely convenience. Not everyone lives close to an urban centre or shopping mall or indeed has time to go shopping. As consumers become ever more comfortable conducting social and commercial activities online, Asos is well placed to take advantage of its position as a fashion e-tail pioneer and capitalize on the ease and interactivity of internet shopping.

The Zara and Asos examples illustrate the standard criteria for competitiveness within a fast-fashion market:

•Cost

•Speed

•Fashionability

•Convenience

When a retail brand competing in this market achieves one or more of the standard measures of competitiveness, it raises the bar for others to match or surpass and eventually new platforms for differentiation and advantage emerge. Companies or brands that find the differentiating element above and beyond the standard will steal the advantage. While Asos certainly gains competitive advantage by throwing convenience into the mix, it also offers something more; shopping online can also be engaging, interactive, informative and dynamic. The company raises the stakes even higher by taking the competitive game to an emotive level. What this cutting-edge e-tailer is able to do is to tap into the desires and aspirations of the celebrity conscious fashion consumer and satisfy their craving to dress like the rich and famous. Key weapons in the Asos armoury are its online community and magazine style blog; these keep users up to date with the latest fashion news and celebrity sightings. Users who want to dress like their favourite celebrity are directed effortlessly to the appropriate page on the Asos transactional website so the opportunity to dress like a star is only a click away.

Keira Knightley arrives at the 2006 Oscars in an aubergine taffeta one-shoulder dress by Vera Wang. Asos, the online fashion retailer, picked up on the celebrity trend for one-shoulder dresses and offered similar styles suitable for their customers as soon as the trend took hold.

“Clothes aren’t just plonked on plastic mannequins, they are, to use Asos jargon, ‘catwalked’ – photographed on real models who twirl around to infectious music.”

Lisa Armstrong

Unique selling proposition

Asos has set itself apart, not only because it was one of the first companies in the UK to make the Internet a viable fashion retail destination but also because it provides a unique ‘As Seen on Screen’ ideology. This is what gives the Internet brand its distinctive emotional pull and provides its unique selling proposition (USP) or unique selling point. A USP represents the fundamental distinguishing proposition being offered to the customer. It is the synthesis of a brand’s positioning and differentiation and should encapsulate its overall competitive advantage. The unique selling proposition is a marketing tool that can be used to emphasize and articulate specific points of difference that make a particular product, service or brand unique and therefore distinctive in the marketplace.

A timeless signature style

Coco Chanel

Coco Chanel was renowned for her signature personal style, often challenging the dress conventions of her day; she wore black, for example, a colour more traditionally associated with mourning. Accessorizing her quintessential look with copious oversized strings of pearls, Chanel created quite a stir with her dramatic costume style jewellery in an era when the wearing of ‘fake’ jewels would have been a novelty. The custom at the time would be to embellish outfits with precious or heirloom jewellery so as to indicate wealth and status. Key elements of her signature style are the little black dress, the classic Chanel suit with gilt buttons, costume jewellery and the quilted handbag. These emblems have become the established signifiers of the brand. They are so powerful that they are reinterpreted and used season after season, and not only for the clothes. The set of the Autumn/Winter 2008/9 ready-to-wear show at the Grand Palais in Paris showcased these brand icons. A gigantic central carousel was decorated with colossal strings of pearls, quilted handbags, bows and costume jewellery.

Chanel wearing her signature pearls, photographed by Boris Lipnitzki in 1936.

A colossal Chanel quilted bag adorns the carousel-style catwalk.

Models on the carousel decorated with giant versions of the Chanel signature emblems at the Autumn/Winter 2008/9 ready-to-wear show in Paris.

Signature style

For many designers or fashion brands it is their unique signature style that helps define their USP. A signature style is a look that is so clear and distinctive that it can easily be attributed to the designer or brand in question. It is also possible for an individual to have a signature style. Karl Lagerfeld, for example, has an instantly recognizable and clearly defined personal style, as has the designer Vivienne Westwood.

For a fashion designer, developing an individual signature style or being able to interpret the style of an existing fashion company is an advantageous and important skill. It is usual for designers to work for several different fashion companies during their career and with each move to a new design label, they will be expected to adapt quickly and produce designs that fit the signature style of the design label or brand. Marco Zanini, for example, was at Dolce & Gabbana and Versace before taking on the role of Creative Director at Halston in 2007 and then moving to Rochas in 2009 to relaunch Rochas fashion. Many designers use their time working for others to hone their skills and experiment with a variety of styles until their own distinctive style emerges and they feel ready to go it alone and launch their own collection.

The British designer Orla Kiely has created a contemporary modern brand that includes clothing, accessories, furniture and homeware products. The brand’s fresh and joyful style is epitomized by the signature leaf design entitled ‘Stem’. This simple and flexible motif represents and embodies the values of the Orla Kiely brand and is used on a diverse assortment of products season after season. The size, colours and application method may vary but the Orla Kiely Stem is instantly recognizable and is fast becoming a modern brand icon.

This diagram shows the steps involved when applying an STP marketing strategy. The first step is to analyse the market and divide it up into smaller, more focused sectors. This is known as segmentation. This process enables a company to better understand the specifics of a market so that they can develop appropriate product targeted to appeal to a particular group of customers. The next step is to analyse competitors so that the brand or product can be positioned within the market and can be differentiated in some way so that it is clearly distinctive from other brands. The ultimate aim when applying an STP marketing strategy is for a brand to achieve a competitive advantage within the marketplace.