4•

Understanding the Customer

Researching and understanding the customer is central to marketing. Indeed, recognizing the requirements and needs of the customer is essential for those tasked with creating and selling fashion products. This issue concerns business at every point in the supply chain from manufacturer to retailer – without customers there is no business, so detailed knowledge of their preferences, motivations and purchasing behaviour is crucial. This knowledge better equips designers, manufacturers and retailers to design, produce and sell products and services that fulfil or exceed consumer requirements.

Not all consumers are the same – each individual will have their own complex set of motivations and shopping behaviour – however it is possible to group consumers into clusters of broadly similar characteristics, needs or fashion traits. This process is known as customer segmentation and is a key feature of STP (segmentation, targeting and positioning) marketing strategy (see page 50). Basic customer analysis can be carried out effectively by a small start-up with limited budget; an example appears later in the chapter showing the type of research carried out by someone setting up their own fashion boutique. A national brand wishing to expand into a new global market may require more in-depth and detailed analysis; for this the services of a professional market research consultancy may be necessary. This chapter explains the basics behind consumer research and analysis and explains the various criteria, or segmentation variables, used to classify and profile existing or potential new fashion consumers. The process of creating a consumer profile will be explained with details on how to write a customer pen portrait. The chapter concludes with information on simple ways to analyse business customers.

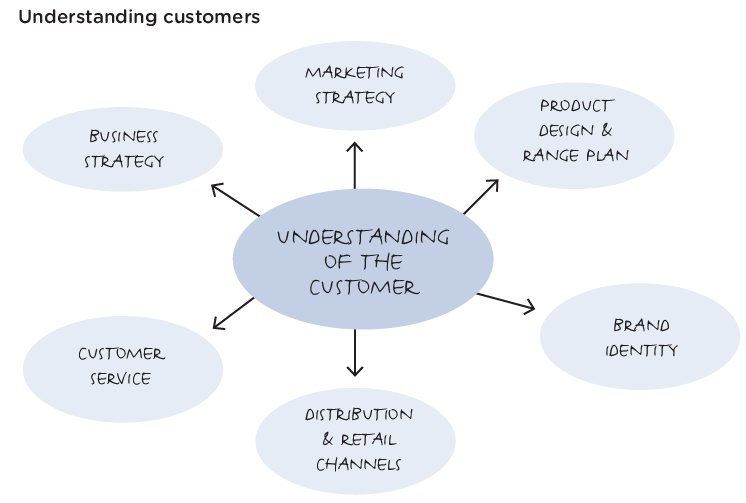

Understanding of the customer is central to all aspects of effective marketing. Many businesses become so focused on internal processes or monitoring the activities of their competitors that they fail to recognize the needs or changing requirements of their customers. Solid background knowledge and understanding of customers is essential and should underpin key business and marketing decisions.

“I dress everyone from students to superstars. The end user is what I am, what I do.”

John Rocha

Before going any further, it is important to establish the difference between the often interchangeable terms of consumer and customer. The consumer, or end-consumer, is the eventual wearer of the product and will generally be the customer who purchases the garment or accessory. However in the case of a baby or small child, while they would be the end-consumer, they would not be the purchasing customer. In this case, a baby- or childrenswear retailer needs to understand not only the special requirements of a baby or child but also the motivations and expectations of the person who purchases the clothes, most generally the mother.

‘Customer’ is a broader term. It can be used to refer to the end-consumer who will be a customer of a particular fashion retailer or it can be used to describe a business customer, which could be a business or organization operating within the fashion supply chain. In the first instance the relationship described is B2C (business-to-consumer). When a business is the customer of another business, it is termed as B2B (business-to-business). A boutique owner, for example, who purchases collections from a wholesale design company is a B2B customer. Companies supplying this boutique must not only have a good knowledge and understanding of the boutique owner as their business customer but also a thorough understanding of the end-consumers or customers who purchase from the boutique.

Customer segmentation

Customer segmentation is one of the key functions of marketing. It aims to divide a large customer base into smaller subgroups that share similar needs and characteristics. Typical criteria for classification are age, gender, occupation, financial situation, lifestyle, life stage, residential location, purchasing behaviour and spending habits. Segmentation helps enhance a company’s understanding of its customers so that it can position its brand and offer products and services designed to appeal to the targeted customers. Lifestyle plays a crucial role in segmenting fashion consumers; clothing needs and style preferences will be highly influenced by a person’s type of work, peer group, and their sporting or leisure activities. Attitudes and opinions on a variety of issues, such as politics, art and culture or environmental issues, might also impact someone’s choice of clothing. When analysing a consumer’s lifestyle and determining what type of customer they might be, the aim is to gain insight about what they buy, why they buy, which companies they purchase from, and how and when they purchase.

Fashion customers will have a variety of clothing needs dependent on their lifestyle and personality. The person illustrated here may be required to wear a traditional suit to work. Outside the workplace they might wish to dress less formally and adopt a more flamboyant or relaxed style.

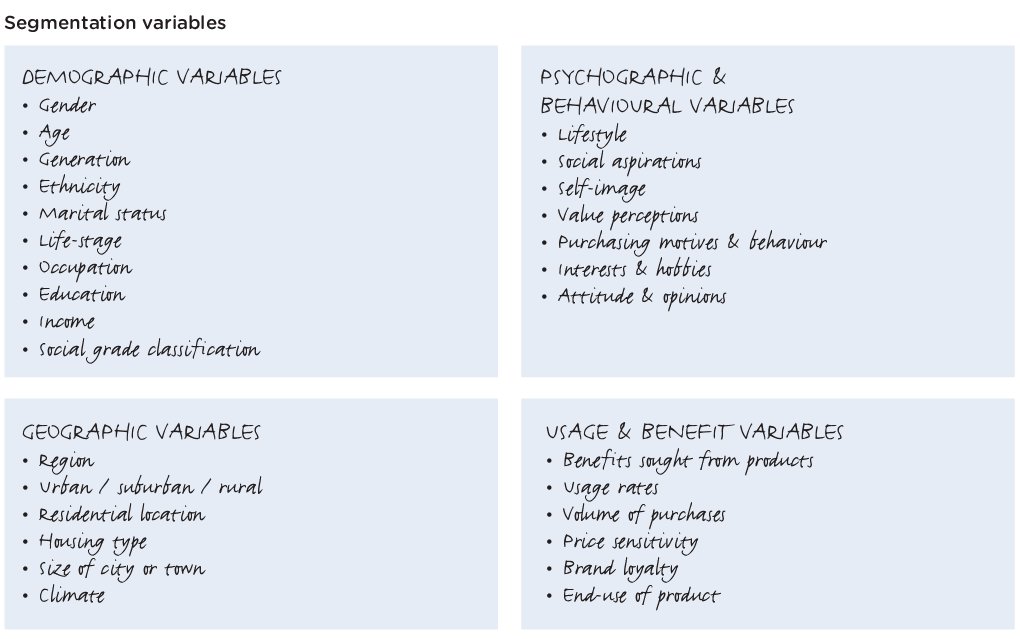

Segmentation variables

At the beginning of any consumer analysis it is important to determine the segmentation variables that will be used to classify and characterize consumers. It is normal to use a combination of criteria; the exact mix will be dependent on the objectives of the research project and the specifics of the company and its market. Traditional segmentation falls into the following main categories – demographic, geographic or a combination of the two known as geo-demographic, all of which focus on identifying who customers are and where they live; behavioural and psychographic segmentation look at the psychology behind consumer purchasing behaviour. Here the idea is to decipher what consumers think, how they behave, why they purchase and what product benefits they require.

Demographic segmentation

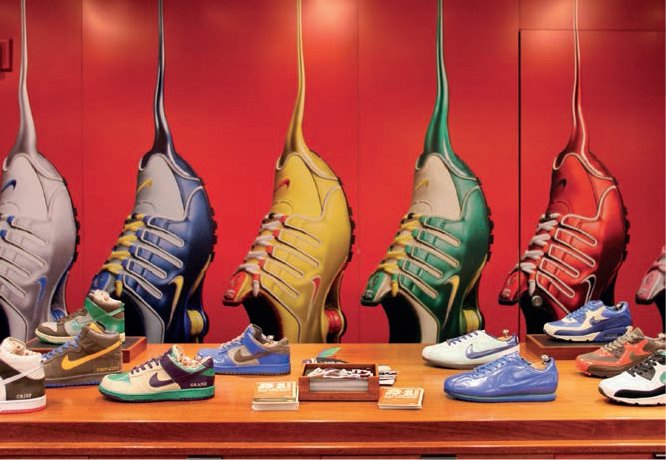

Demographic segmentation is one of the most widely used methods of classification. It uses key variables such as age, gender, generation, occupation, income, life stage and socio-economic status. Each of these factors is extremely important in its own right, but should not be considered in isolation – for example, age. A woman may spend heavily on lounge-wear or exercise clothing for yoga or Pilates; she may work from home and require only casual clothing. Another woman of exactly the same age and stage in her life might be employed in a professional office and need an extensive wardrobe suitable for work. In general men spend less on fashion than women but this is not always the case. Male consumers can be extremely fashion conscious and spend a significant proportion of their disposable income on clothing or accessories. Some young male consumers are addicted to purchasing branded sportswear, trainers or jeans. An article in The Times newspaper on trainer and sportswear addicts by Laura Lovett describes a twenty-one-year-old male who gains kudos by wearing Y-3, the fashion/sportswear fusion brand created by Yohji Yamamoto in collaboration with adidas. This customer explains that while some people collect stamps, he collects Y-3. Gooey Wooey, an avid trainer collector living in southwest England, has a collection of nearly 200 pairs. Gooey trades trainers online, often buying a pair a week or selling some of his prized limited-edition retro sneakers to other enthusiasts.

Nike sneakers on display at the Niketown store in New York.

Gooey Wooey, an avid 36-year-old sneaker collector living in the southwest region of England has a collection of nearly 200 pairs. Gooey trades online, often buying a pair a week or selling some of his prized limited-edition retro sneakers to other enthusiasts. In this image, Gooey shows off one of his most expensive acquisitions, a pair of Nike Dunk Low Pro SB ‘Paris’ sneakers featuring artwork by Bernard Buffet. Only 202 pairs of this limited edition were produced, so they exchange hands for prices in the region of US$4,000.

Demographics also consider the life stage of a consumer; they may still be living with their parents or be single, in a partnership or married, with or without children, or they could have children who have left home. As a person passes through the various phases of life, their priorities are likely to shift and their income and discretionary spend will also be affected. Key stages in the life cycle are:

•Dependent – children living at home, dependent on parents

•Pre-family – independent adults who don’t yet have children

•Family – adults with children

•Late stage or empty nesters – parents with children who have left home, or older people with no children

Market research companies often attribute names or acronyms to different consumer groups as a way to signify stage in life. Examples of this are:

DINKYs – Double Income No Kids Yet

HEIDIs – Highly Educated Independent Individuals

SINDIs – Single Independent Newly Divorced Individuals

NEETs – Not in Employment, Education or Training

YADs – Young And Determined Savers

TIREDs – Thirtysomething Independent Radical Educated Dropouts

KIPPERS – Kids In Parents’ Pockets Eroding Retirement Savings

Another form of demographic segmentation is to classify consumers by generation. This considers the effect of the exisiting political, economic, social and cultural situation someone is born into. More specifically, it takes into account the period when a consumer comes of age as a teenager or young adult, as this will play an important part in shaping their opinions and attitudes on fashion, style, consumerism, branding, advertising and technology. Generational traits can impact the way consumers shop, how they spend money, the types of items on which they spend it and their allegiance and loyalty to certain brands. The following section provides a snapshot of the key consumer generations from baby boomers to Generation Z.

The demarcation between one cohort in the Generation Timeline and the next is not always straightforward and in some cases they overlap or there is a gap. This is partly because the exact dates for the generations differ according to various social commentators or census authorities. Over time, experts analysing demographics and social behaviour are also able to refine their knowledge and attribute more concise date brackets to emerging generations.

Leading edge baby boomers

Baby boomers were originally defined as those born between 1946 and 1964. However this 20-year generation span was later broken down into two groups – leading edge baby boomers (1946–1954) and trailing edge baby boomers (1954–1964). The name ‘boomer’ alludes to the birth rate explosion that occurred during the period of economic stability following the Second World War. As they came of age, baby boomers challenged traditions and adopted styles of dress guaranteed to upset the establishment – long hair for men, the shortest of mini skirts for women. Ironically, baby boomers are now part of the establishment and relatively wealthy in comparison to other generations. However they are increasingly being left out in the cold by fashion companies keen to reposition their brands in order to attract young professionals or the youth market. The boomer generation should not be forgotten – in their heads they are still young, and they still want to look current and fashionable. The trick with this group is to provide good service, better quality and offer stylish clothing with excellent cut and fit.

Mary Quant stands with models wearing her Viva Viva collection in 1967. Quant opened her boutique, ‘Bazaar’ on London’s King’s Road in 1955, selling clothes designed to appeal to the burgeoning youth market.

Each week The Guardian newspaper runs an ‘All Ages’ fashion feature in its Saturday magazine, championing diversity and challenging perceived notions of fashion. Though an important demographic variable, age is not always the best indicator of a consumer’s style or what they might purchase. A fashion retailer might stock thousands of units of a particular garment and quite often two women, one thirty-five and another fifty, will purchase the same item. Mary Portas, Creative Director of Yellowdoor communications, calls this important customer segment ‘The Forever 40s’. The customer may be in her forties but could also be fifty, sixty or even older. This customer group is connected not by age bracket but by fashion attitude, style and purchasing choices.

Trailing edge baby boomers (aka Generation Jones)

The name ‘Generation Jones’ was coined by American sociologist Jonathan Pontell. Derived from the slang ‘jonesin’, the name relates to feelings of craving, fuelled by unfulfilled expectations. Pontell identified a generation born in 1954–65 that had mistakenly been lumped in with the boomers, but which was actually a separate group with distinct characteristics. Douglas Coupland wrote

“Jonathan has it right. My book Generation X was about the fringe of Generation Jones which became the mainstream of Generation X. There is a generation between the Boomers and Xers, and ‘Generation Jones’ – what a great name for it!”

Generation Jones is a powerful demographic representing 26 per cent of the US population, with almost a third of the spending power, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of the Census. Research carried out by Carat identified that they represent 20 per cent of the UK adult population (www.projectbritain.co.uk 2009). Barack Obama is Gen Jones and many political commentators believe that it was the Joneser vote that brought him to power (www.huffingtonpost.com 2009). Generation Jones’ attitudes and tastes were shaped by the political, social and cultural events of the 1970s and early 1980s. Financially they have been affected by negative equity in 1990s and the current breakdown of the pension system.

“I don’t have an ideal, just someone who genuinely likes my clothes, between 18 and 81.”

Erdem Moralioglu

Generation X

Generation X was the title of a book written by journalist Jane Deverson and Charles Hamblett in the 1960s, but the term came to prominence many years later when Douglas Coupland published his novel, Generation X, Tales for an Accelerated Culture, in 1991. Described as a lost generation, this demographic came of age in the 1980s and early 1990s, shaped by the Thatcher and Reagan years. Affected by escalating rates of divorce, fear of AIDS, recession, job insecurity and the potential of employment in a menial ‘McJob’, this disaffected generation, also termed as ‘slackers’, sought comfort by creating their own self-sufficient culture and alternative tribal family unit of close-knit friends, as illustrated by the television shows Friends in the United States and the British drama This Life. As Gen X has grown up and matured, they have cast off their more juvenile slacker habits and morphed into ‘yupsters’, creative urban professionals who endeavour to balance the personal with wider social concerns of family, community and work. Yupsters manage to maintain an intricate set of contradictions; they are corporate but have hip individual fashion style, business minded but independent and entrepreneurial in spirit. They value family time and aim to work smarter not harder.

Generation Y

Generation Y, also known as Millennials, are according to Howe & Strauss, those born after 1982, although others have classified them as born between the late 1970s and the mid-1990s. This generation are the children of Gen Jones; they have experienced pressure from parents to succeed and overachieve, money has been spent on their education and those with a college education are likely to start their working lives paying off sizable student loans. For this reason Gen Y have also been given the rather depressing title of the IPOD generation; Insecure, Pressurized, Over-taxed and Debt-ridden, a name coined by Bosanquet & Gibbs in the report Class of 2005: The IPOD Generation. This generation also includes the post-1980s children born in China during the one-child policy. Millennials have grown up with technology and increasingly live their lives online; they are plugged-in and globally connected. They understand branding and are media and marketing savvy, they communicate using social media, form online communities and are happy to create their own online content. A study carried out by Robert Half International in association with Yahoo! Hotjobs in the US (2007) found that 41 per cent of Gen Y workers surveyed want to dress in business casual, 27 per cent prefer jeans and sneakers, 26 per cent prefer a mix depending on the situation and only 4 per cent stated they preferred business attire.

Celeste, a hip hop tap dancer living in New York belongs to Generation Y. Communicating online and belonging to an online community is normal for this media-savvy generation. Celeste is a member of lookbook.nu, an invite-only community sharing fashion inspiration from real people around the world.

Celeste wears a ripped-up, mended T-shirt and skinny jeans, both hand-me-downs from an ex-boyfriend. The beautiful bag and shoes are finds from a vintage store in Brooklyn.

Generation Z

There is still much debate as to the dates and characteristics that define this generation. Some say the generation consists of those born after the mid-1990s; others such as Howe and Strauss believe it is those born from 2004 onwards. What can be said is that they are the offspring of Gen X and Y and their grandparents will be baby boomer or Gen Jones. This generation will take the Internet for granted and have no knowledge of a time before World Wide Web. They will be the Web 2.0 generation and beyond.

The table of 20th- and 21st-century generations gives guideline dates for generational cohorts. The table also indicates the decade of influence affecting each cohort as they come of age as teenagers or young adults, which is when they are most likely to form their attitudes, opinions and approach to life.

Geographic segmentation

Geographic segmentation analyses customers by region, continent, state, county or neighbourhood. This type of information is important to consider, particularly as fashion markets become ever more global and retailers and brand managers are required to understand the particular needs of customers in each of the countries or regions where they do business. The product offering, marketing and promotional approach may need to be adjusted in order to address differences of climate, culture or religion. It is also important to consider whether someone lives in a city, large town or the countryside, as this will affect the types of shops accessible to the customer.

Geo-demographic segmentation

Geo-demographic segmentation makes use of a combination of geographic and demographic analysis – this can be far more effective for understanding the social, economic and geographic make-up of a population. Geo-demographic analysis divides a country up and then analyses each geographic subdivision demographically. It is particularly useful for helping retailers determine which locations might be the most profitable or how best to adapt stores to fit with the geo-demographic of a location. Research shows that consumers can show strong attachment to their local area, carrying out shopping and leisure activities 5–23 km (3–14 miles) from their home or place of work. Matches is a boutique fashion retailer with a small chain of high-class womenswear and menswear stores situated within London. The owners of Matches recognize that London consists of many small ‘villages’ and customers prefer to shop close to home or work. Each store has its own fashion profile designed to cater specifically to the unique style characteristics of the local customer. The boutique in Marylebone High Street, central London, is situated in a locale that is both residential and work-based. There are cafés, boutiques and hip art galleries, so in a bid to attract the art-loving demographic who live and work nearby, the store has been transformed into an innovative retail/gallery space where fashion and art can coexist. The Wimbledon shop, by contrast, has a more intimate style better suited to the village atmosphere of its local residential area.

Geo-demographic analysis and consumer profiling can be carried out using the services of a market research and analysis consultancy, which will have access to sophisticated database profiling systems. However a small business can carry out simple but effective research using basic census data, free online postcode analysis, statistics from the local council, and fashion industry information on market trends. The example on pp.114–15 describes the basic geo-demographic background research carried out by a boutique owner as she prepared to launch her business.

Geo-demographic analysis tools

There are several proprietary geo-demographic neighbourhood classification systems, such as ACORN (A Classification Of Residential Neighbourhoods), Mosaic and Super Profiles. These database analysis tools use government census data, postcode or zip code analysis and a complicated array of demographic and lifestyle variables to segment populations by neighbourhood and social status. The ACORN Classification Map, created by CACI Ltd, divides the UK population into five categories: Wealthy Achievers, Urban Prosperity, Comfortably Off, Moderate Means and Hard Pressed. These are then divided into 17 subgroups, some examples being: Affluent Greys, Flourishing Families, Blue Collar Roots, Settled Suburbia and Aspiring Singles. These groups are then further subdivided into 56 consumer types.

The Mosaic Global system devised by Experian is available in Europe, North America and the Asia-Pacific region. The population is divided into ten neighbourhood types, US examples being: Affluent Suburbia, Upscale America, Metro Fringe, Urban Essence or Remote America. These groups are then further broken down into 60 subgroups.

The Super Profiles Geodemographic Typology was developed by Batey and Brown in 1994 in collaboration with CDMS Ltd, part of the Littlewoods home-shopping organization. The Super Profiles system features three levels. The first has ten lifestyle profiles, some examples being: Affluent Achievers, Thriving Greys, Settled Suburbans, Nest Builders, Hard Pressed Families and the Have-Nots. This level is divided into 40 target market clusters which are then subdivided into 160 specific profiles.

Psychographic and behavioural segmentation

Psychographic and behavioural segmentation analyses consumers based on their lifestyle and personality type. The purpose is to determine the underlying motivations that drive a person’s attitude or behaviour as a consumer. It is possible for consumers to have similar demographic profiles but entirely different attitudes to clothing and appearance. One person, for example, might believe that they must look crisp, smart and well turned-out for all occasions, whereas someone else might choose to wear expensive branded fashion that looks worn and battered even when new, giving the impression they don’t care how they look. Psychographic, behavioural and lifestyle studies aim to gain further insight into consumer attitudes, interests and opinions (AIOs) and understand how these influence a person’s fashion needs, desires and purchasing choices. This is a complex topic, especially when it comes to attitudes to fashion. If you remember, the aim of marketing is to satisfy consumer needs and wants and, while it is fair to say that we may want or desire new clothes, most western consumers certainly do not need more clothes, accessories or shoes. The reality is that many of us have brand new items in our wardrobes that remain unworn; we give copious amounts of unwanted clothes away to charity shops (although the amount has decreased since the recession) and we cast an alarming amount of surplus clothes into landfill. So what is it that motivates us to continue purchasing even if we do not theoretically need anymore or can ill afford it? The answer lies in psychology and the theories of human motivation.

Psychographic and behavioural analysis aims to gain insight into consumer attitudes, opinions, interests and purchasing behaviours, which in turn will influence the way a person chooses to dress. A person who believes they must look stylish, appropriate for the occasion and well turned-out may spend a great deal on clothes and take great care with their appearance.

Consumer motivation and behaviour

What motivates us to buy into fashion, what influences our purchasing behaviour, how do our attitudes, interests and opinions affect our purchasing choices? At a simplistic level it could be said that the motivating force to purchase a garment, handbag or pair of shoes is a real physical need; in other words we do not have a receptacle in which to carry our keys, money and mobile phone, or a pair of winter boots to protect us from the cold and wet, so in order to satisfy this need we must purchase the required item.

The reality is that in most cases the motivation is more akin to desire and the need is psychological. Danish brand guru and futurologist Martin Lindstrom argues in his book Buyology: How Everything We Believe About What We Buy Is Wrong that the motivation is neurological and University of New Mexico evolutionary psychologist, Geoffrey Miller, contends in his book Spent: Sex, Evolution and the Secrets of Consumerism that evolutionary biology is behind our need to purchase and display conspicuous consumption. Miller’s theory of ‘display signalling’ proposes that we wear certain fashion styles or brands labels in order to signal specific qualities of character to others. Someone wearing an ethical or eco-fashion brand, for example, is at some level trying to communicate that they are conscientious. A person wearing conspicuously branded designer labels is advertising qualities of wealth and desirability, while someone with an active and sporty style is trying to signal their health and fitness.

Researching your target market

Starburst Boutique

Starburst Boutique is an independent retailer situated in the beautiful and historic coastal town of Dartmouth in southwest England. The boutique offers a unique blend of womenswear and accessories from a host of international designers including Day Birger et Mikkelsen and Rützou from Denmark, Armor Lux and Petit Bateau from France as well as UK labels, Marilyn Moore, Pyrus, Queen and Country and Saltwater. Running alongside the contemporary womenswear collections are one-off vintage pieces, bespoke jewellery and luxurious lifestyle products. The boutique is situated in Dartmouth’s most exclusive shopping street and its stylish and relaxed in-store atmosphere is reflective of its coastal setting. It is designed to attract affluent second-home owners, weekenders and tourists, but also to provide local clientele with a chic destination in which to buy exclusive and desirable fashion brands.

Background market research

Starburst Boutique owner and buyer, Hannah Jennings, carried out detailed research in order to set up her business. Investigation of the current status, trends and predicted future of the independent retailing sector and the UK womenswear market was carried out; relevant data was obtained from trade magazines such as Drapers and Retail Week, industry analysts such as Mintel, WGSN, Fashion Monitor and the British Retail Consortium, as well as a range of relevant websites, magazines and newspaper articles. Information on the demographic of the local area and tourism were sourced from the local and county councils. Jennings also carried out an extensive investigation of existing independent retailers within the locale, including the nearest city, 40 km (25 miles) away. She also travelled to other cities such as London, Edinburgh, Winchester, Bath and Brighton to visit similar stylish independent boutiques.

Research findings and information

Tourism makes a significant contribution to the local economy. Research revealed that Dartmouth attracts 400,000 visitors a year plus an additional 100,000 during a festive regatta week held in August. Sixty per cent of those visiting the area can be economically grouped as ABC1. More UK residents are choosing to take vacations within Great Britain and a resurgence in popularity of seaside towns is highlighted by data released in 2008 that shows footfall in seaside towns grew 4.9 per cent compared to 1.3 per cent in all towns and cities. The local area also boasts the third highest percentage of second-home owners in the UK, and has experienced a net population increase of 441,000 since 1996 – a result of people migrating to the area in search of a better quality of life. Jennings found market data published in Drapers which revealed the UK womenswear market to be worth in excess of £17 billion in 2008, with the independent retailers’ market share at just under 7 per cent. Data from a 2007 British Retail Consortium survey identified a growing proportion of UK consumers who preferred not to shop at high-street multiple retailers, and retail expert Mary Portas backed this up with a prediction that customers in their thirties will spend less on fast fashion and transfer their allegiance to local shops where they can invest in quality product and receive a higher quality of personal service. Research also indicates that female shoppers stay ‘younger for longer’ and that once they have defined their personal style in their thirties they will want to continue purchasing chic, contemporary and stylish clothing through to their sixties and beyond.

Conclusions – the Starburst Boutique customer

Hannah Jennings recognizes how important her background research has been in helping her understand the Starburst Boutique customer and the potential of the market.

“The customer profiling I did turned out to be very accurate with regards to my core customers. It is fundamental for my business and I now buy with that segment in mind.”

Hannah Jennings

The Starburst Boutique target market can be split into two customer profiles. The first represents the core customer to the business, namely women aged 30–45 who are married with small children. They either have a second home in the area or are weekender or tourist visitors who aspire to coastal living. The second customer profile is represented by slightly older, locally based women, aged 45–60 or over, probably with grown-up children and possibly grandchildren. The 60+ market is important to the boutique as this customer might bring along daughters or even granddaughters. They too may love the chance to shop in the store’s chic and laidback environment and snap up something desirable to wear on their holiday or to take back home.

“Independent retailers offer a personal service and cultural understanding of the local market.”

Mary Portas

Consumer purchase decision process

It is evident that fashion purchasing decisions are rarely based on logical criteria alone. The motivations behind our purchasing behaviour are driven by a complex interplay of demographic, geographic, psychological, neurological, economic, social, cultural and personal factors. Research indicates that consumers go through a decision-making process when they purchase a product. The basic steps are as follows:

•Recognition of need

•Information search and identification of options

•Evaluation of options

•Decision

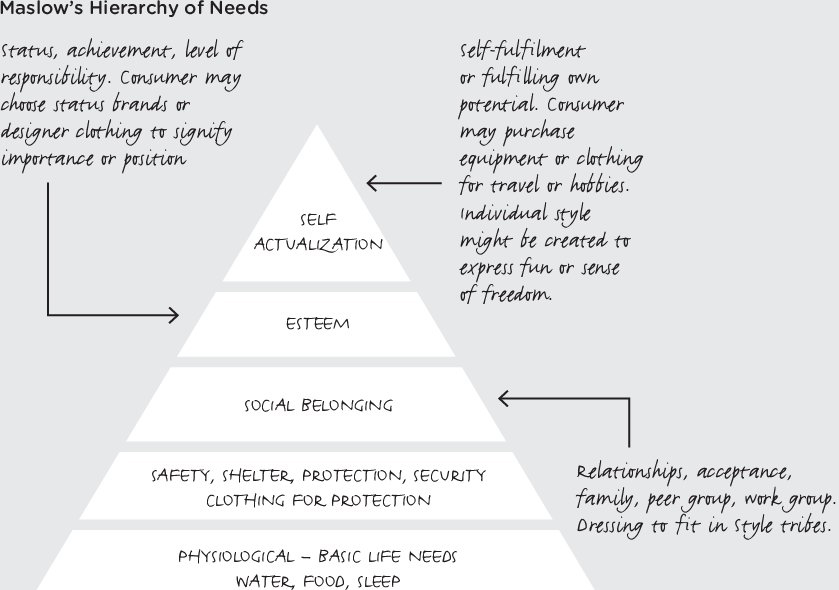

Abraham Maslow developed his theory in 1943 and proposed a five-tier hierarchy, starting with basic-level physiological necessities such as food, water and sleep and progressing up through needs of safety, social belonging and esteem, culminating in the highest level of need driven by the motivation for self-actualization, which could also be viewed as self-realization or self-fulfilment. The original premise being that an individual would attempt to meet their needs at the lowest level before advancing to the next level. In reality individuals attempt to meet a variety of needs simultaneously and do not progress up the hierarchy in a prescribed manner. In modern society we do have a basic physiological need for clothing to protext us from the elements, but in most cases consumer motivation regarding fashion need is triggered by a diverse set of desires and stimuli. These might relate to social belonging, gaining approval, affiliation with a group or notions of self-acceptance and esteem.

A consumer’s attitudes, preferences and motivations will influence their purchasing behaviour. This table presents possible purchasing behaviours associated with a variety of potential motivations. If someone’s motivation is to get a bargain, for example, then this will drive certain behaviours, such as shopping during the sales, signing up to a discount website like Vente-privee, or scouring vintage stores for that special bargain.

Source: Adapted from Tom Peters (2005)

The decision process starts with the recognition that there is a need. This might be a valid physical need; a person may gain or lose a significant amount of weight and need to purchase new clothes to fit. A couple may be planning a traditional wedding and therefore need to purchase or hire appropriate outfits and accessories. The need could be cultural – a person travelling to a country where the convention is to dress more modestly may need to acquire a long skirt or a top with sleeves and a high neckline. It is more likely, however, that the need will arise at a sub-conscious level. If a person thinks, “I look old and frumpy, no one will find me attractive”, deep down they believe they lack something. The belief sets up what could be termed as a false deficit in their mind, the discrepancy between what they believe is lacking and what they desire creates the sensation of need; “I need a fresh look. I’d better buy some new clothes.” This thought becomes the motivation, leading towards action and a potential decision to purchase.

Once a need has been established, the next stages are to search for information and check out and evaluate options. This could occur by visiting shops, going online, reading magazines or gathering opinions from friends. However, these steps are very much dependent on the situation and the person in question. Some people may devote a great deal of time and energy to research and evaluation; others might be less cautious, less willing to spend time and generally more spontaneous. Research and evaluation are perhaps less relevant for fashion purchases compared to buying a car or expensive piece of furniture. Nonetheless there are those who enjoy the process of checking out what is available, browsing, trying on clothes or hunting down a bargain. A potential purchaser may decide upon a selection of brands from which to choose; the brands in serious contention for the consumer’s purchase are known as the consideration set.

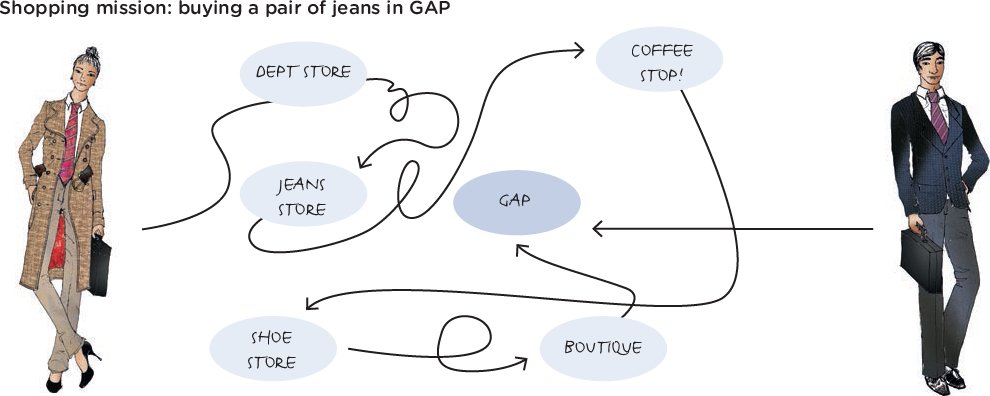

This cartoon puts a humorous spin on the different behaviour of women compared to men when shopping for fashion. The man heads straight to Gap and purchases a pair of selvedge jeans for around US$89, taking about 20 minutes to complete the mission. The woman on the other hand completes a more circuitous journey, she visits several shops, takes more than two hours to complete the mission and spends more than US$300, purchasing designer jeans, a pair of shoes and some make up!

Fashion purchases are often unplanned, impulse buys usually being the result of spontaneity combined with opportunity. Impulsive purchasing may occur as a result of a shopper experiencing what could be termed a ‘shopping high’ or ‘buying buzz’. It has been proven that shopping can produce a surge of excitement generated by the brain as it releases dopamine, a chemical involved in the experience of feeling pleasure. Habitual shopping patterns could also be linked to this phenomenon – someone might always go shopping on the day they get their pay cheque, the heady combination of money and shopping producing an elevation in mood.

A highly skilled artisan makes a pair of finely crafted leather shoes for Italian brand Tod’s.

Other factors may also affect the consumer’s choice, such as the country of origin of a product or brand. Consumers may have a positive perception of particular goods from certain countries: Italian leather, French lace, Scottish cashmere and tweed or British tailoring are examples. This is known as the country of origin effect (COO or COOE). It is not only the country of manufacture that can affect perception but also the country of design (COD). In this instance the product may be designed in a country renowned for a particular design skill but manufactured elsewhere – Swedish-designed furniture, for example. There are strict trade laws concerning country of origin so it would be illegal to label garments incorrectly. However it is possible to create and market a brand with an identity that is suggestive of a particular country. The UK fashion brand, Super Dry Japan, was set up after an inspirational trip to Japan. Garments are embroidered with Japanese-style writing and given names like the ‘Osaka’ T-shirt.

Adoption of innovation and trends

Consumers will vary in their response to new trends and ideas. Those who are more conservative or reticent might take some time before they feel ready to buy into a new or developing trend. They might want to feel safe, fit in or not look out of place. Others might feel that a new innovation or style is too expensive. They might wait till the trend hits the mass market and the price comes down; their motivation is to be cautious and spend wisely. There are others who like to be on the cutting edge of style. They may purchase the new season collections at the earliest opportunity; they want to be the first, be noticed or stand out from the crowd. The way in which an innovation, new idea or trend is taken up by consumers and moves through a population can be explained using Everett Rogers’ diffusion theory. Rogers identified five types of individual classified by their propensity to adopt innovation.

Innovators – a small percentage of adventurous people who initiate trends or adopt innovations before others. They are risk-takers and visionaries. Designers such as Vivienne Westwood, or John Galliano for Dior Couture, would fit into this category, along with those that innovate and instigate subculture and street trends.

Early Adopters – people who take up a trend in the early stages, often cultural opinion leaders or those that disseminate fashion, style or artistic ideas. This group accepts and embraces change and enjoys new ideas. They will have the confidence to follow or adapt the trend, mix styles and create the desired look from designer, boutique, high-street and vintage.

A trend will originate within the innovator group of individuals, adventurous types who are cutting edge in their ideas. As the trend takes hold a tipping point will be reached. This is the moment when the trend or idea crosses a significant threshold; the adoption rate increases exponentially and the trend spreads rapidly and reaches the mass market. Eventually the trend will peak and begin its decline. The late majority purchase the trend just as its fashionability and mass market appeal begin to dwindle. Laggards are those at the tail-end who just manage to cotton on to the idea when it is already too late and the trend is over.

Source: Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations (1995)

Early majority – represents the main bulk of people who adopt a trend as it gathers momentum and begins to penetrate the mass market. This group is likely to take up a trend after they have seen it worn by others or in fashion and gossip magazines or recommended on blogs or websites.

Late majority – those who buy into a trend when it is already very well established and reaching its peak or beginning to decline.

Laggards – these people do not take fashion risks, and are the last people to catch on to a trend, usually when it is already too late.

Rogers proposed a five-stage Mechanism of Diffusion model to explain the decision process that an individual follows in order to progress from first knowledge or awareness of a new trend or product innovation through to adoption of the trend or purchase and evaluating their decision.

Purchasing a new innovation

The FitFlop shoe

The stages described in Rogers’ Mechanism of Diffusion can be seen in action in this example, which relates the actual steps a purchaser went through from first awareness and knowledge of an innovative new product (FitFlop shoes), to final decision to purchase – a process that took well over a year. The example demonstrates not only the way in which a new product innovation is accepted and purchased by a consumer, but also the integrated nature of marketing. It wasn’t just press articles or advertising that persuaded this person to buy, but a complex combination of factors including publicity, information on the benefits of the new technology, the design and look of the FitFlop, its pricing comparative to other shoes in both the fashion and tech-shoe markets, the recommendation of a friend, and seeing the distinctive footwear worn by others of a similar tribe.

1.The product is brought to the attention of the consumer in early spring 2007 when they read a promotional article in the press.

2.The potential consumer, who has gained awareness of the product is further reminded of the FitFlop when they see another press article later in the year. They become curious about the product and their interest is raised.

3.The potential consumer continues to see adverts and press articles during spring 2008. They observe people wearing the distinctive FitFlop. Tempted by the price – cheaper than shoes of another brand using similar technology – the consumer begins to persuade themselves that FitFlops might be just what they need.

4.They encounter a friend who owns a pair of FitFlops; the friend communicates positively about the shoes. The consumer is further persuaded and decides they want a pair too.

5.Finally, in summer 2008, the consumer sees the FitFlops in a store window and decides to purchase. They wear the FitFlops and find them extremely comfortable. The purchaser is very happy with product.

6.The purchaser tells friends about FitFlop shoes. The process now moves to a new stage of word-of-mouth recommendation. Knowledge and awareness of the innovative product is transmitted to new people following Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations model.

The Walkstar FitFlop. The shoe’s USP is the innovative technology used for its patent-pending sole, made of multi-density material that supports and exercises leg and buttock muscles as the wearer walks. The sole’s ‘wobble board’ effect creates extra tension in the muscles, causing them to work harder. The shoe quickly made the transition from fitness product to ‘fashion must-have’ with new, more fashionable designs such as the Liberty Print Obi FitFlop, or the Electra sequinned version for Summer 2009.

1.Knowledge – the particular product or trend must come to the attention of the potential consumer. They gain initial knowledge of uses, benefits or key ideas behind an innovation or trend. This could be because they read about it in the press or see others wearing or using the product.

2.Persuasion – the person forms an opinion about the product. They may be persuaded by the opinions of others. If it is of interest to them, they might begin to desire the product and persuade themselves that it is suitable, useful, a good investment etc.

3.Decision – the person makes a decision to adopt the innovation or trend; in other words they take action and purchase.

4.Implementation – the person uses the product.

5.Confirmation – the person evaluates the results of their decision and compares actual usage of the product with original perceptions.

Consumer trends

Identifying and understanding consumer trends is a vital element of fashion market research. Observing consumers and gathering information from markets around the globe keeps you up to date. The trick is to keep an eye out for innovators and early adopters; they are likely to be ahead of the curve. Trend watching helps you to develop intuition, spot new ideas and gain inspiration. Remember consumer needs will change in response to political, economic and social change. Trends come and go but here are some things to think about…

“If you knew everything about tomorrow what would you do differently today?”

Faith Popcorn

Frugal cocooning – The American futurist Faith Popcorn came up with the concept of cocooning way back in the 1990s. The trend has re-emerged in response to the recession. Frugal cocooning is all about staying in and hunkering down. Think cosy knits, comfy lounge-wear and slipper socks.

Generation G – G for generosity, people reacting against greed. Growing online culture allows them to share, give, engage, create and collaborate. Think clothes swapping, skill sharing, freecycling or random acts of kindness (RAK).

Sellsumers – Consumers no longer just consume, they sell creative output to corporations or fellow consumers. The global recession combined with online democratization means more consumer participation in the world of demand and supply.

Cosy childhood memories – Nostalgic items remind us of childhood days – 50s florals, tea-time cup-cakes, board games, storage tins with 60s and 70s branding. Baby boomers and Gen Jones desire to feel cosy and secure in tough times.

The lipstick effect – Tough times mean consumers go for ‘tradedown’ spending; they forego extravagant purchases and opt for small feelgood treats like lipstick.

Cocooning and frugal cocooning are trends that emerged in response to the recession. The idea is to stay at home, spend less and wrap up in comfy clothes and cosy knits.

Perfect pieces – Fed up with product overload, consumers want well-considered fashion items. Perfect basics that offer more, beautifully crafted quality pieces designed to last; classic fashion emblems such as the perfect trench, the little black dress, a striped French matelot T-shirt or sweater or Japanese selvedge jeans.

Addicted to niche – Consumers want to find an intricate balance between being one-of-a-kind and fitting in. This is ‘niche’, just enough to form a tribe but not too many, not a crowd; this is about being one of the few. Niche brands come with a story – niche is knowledge, niche is the kudos of being in the know.

Fashion online – An increasing number of consumers are purchasing fashion online. The web has democratized fashion, making it available to a much wider group of consumers. Not everyone lives near a major shopping centre, and some shoppers feel intimidated entering certain types of fashion store, or they feel embarrassed when clothing does not fit or suit. Fashion e-tailers are experiencing phenomenal growth; Vente-privee, the membership-only e-tailer, achieved sales of £545 million in 2008. The French-owned company, with members across France, Germany, the UK, Italy and Spain, holds online sales events, with luxury fashion and designer brands selling for 50–70 per cent below normal retail price. The British online retailer, Asos, reported sales up 104 per cent, reaching a figure of £165 million for the year ending March 2009.

“Online fashion has changed everything. It’s made fashion accessible physically and psychologically.”

Jackie Naghten

Once consumer research and analysis is complete, the next step is to create a consumer profile report to describe the consumer groups being targeted. The report should give background demographic, geo-demographic and psychographic data, information on current or emerging consumer trends, current sales statistics and relevant observational data. It is normal practice for personnel such as buyers, marketing or brand managers, or designers to give presentations summarizing the consumer report to other staff members or to suppliers, partners and stakeholders. A technique used to précis the research and describe the customer is known as a customer pen portrait. This written description can be enhanced by the addition of a customer image and lifestyle visual shown on a display board or using PowerPoint or Flash presentation.

Questions for a pen portait

Try to visualize the person, get inside their head and imagine who they are. What influences are there in his or her life? What are their key concerns, opinions or interests?

Think about their routine as they go through the day. Do they have specific clothes or outfits for work, sport or leisure? What nonclothing brands are important to them and why?

Writing a customer pen portrait

A pen portrait is a short, written profile that describes the characteristics and traits of a core customer, representative of the target market. The portrait provides a composite picture of the target consumer, which should be built up using information gathered from primary and secondary market research. The portrait should present a realistic and factual description of the consumer demographic, age or age bracket, lifestyle, fashion style, brand preferences, purchasing motivation and attitudes towards purchasing fashion.

Make sure you define their age and gender, describe their lifestyle, social status and stage of life. You can list the clothing brands that they wear or aspire to wear and indicate how much they spend on clothing. The problem with pen portraits is the tendency to describe a fantasy life or the aspirational life of the consumer rather than the reality; it is important therefore to reiterate that the portrait must be based upon researched information and data. Information can be obtained from government demographic statistics, articles in the fashion media, fashion trend publications and websites, blogs and by carrying out a customer questionnaire.

A visual depiction of the customer and their lifestyle is a useful addition to the written portrait. This can be created using a collage of images taken from magazines as well as your own illustrations. Consider magazines that cover interiors, lifestyle, food, gardening, sport, gadgets or technology. When creating a visual profile, it is important to ensure that images reflect the consumer’s lifestyle and activities and not just their approach to fashion. Try to use pictures that typify the product or brand choices for that consumer type such as their car, watch, scent, accessories and clothing. The images chosen should reflect accurately the market level and status level of the customer.

Building a customer profile

The niche denim market

Sliced Bread is a fresh new denim brand created by James Hayes while still a student studying fashion at Plymouth College of Art in the UK. The idea was developed in response to increasing consumer demand for authentic, stylish and nostalgic product. The Sliced Bread concept is simple; to make quality jeans and T-shirts that people will remember. Each piece is hand-made in England using the finest ingredients and production methods. Sliced Bread products are transeasonal and 100 per cent fresh!

Researching the customer

James carried out face-to-face, telephone and Internet interviews with young men in their early twenties who might be potential customers for Sliced Bread jeans and T-shirts. He wanted to gather more information on their lifestyles, the type of brands they currently wore and find out more about which brands they aspired to wear. James discovered how much they spent on clothes, what they did for a living and how they spent their leisure time. After conducting a number of interviews, James noticed commonalities in terms of purchasing behaviour, attitudes and brand preferences that appeared to typify the traits of the sample group. James used this information to compile a customer pen portrait for a character he named ‘Jason Powell’, who would be representative of the target audience for the proposed Sliced Bread brand.

Images of James Hayes’ Sliced Bread jeans and T-shirt collection.

Pen portrait of a Sliced Bread customer

Jason Powell is a twenty-one-year-old student studying architecture at Manchester University. Now in his second year of study, he has rented a student flat with three friends. In the holidays he lives with his parents in Windsor, about 50 km (30 miles) outside of London. Jason is entrepreneurial and aspires to set up his own design business. He already communicates online with other young architects and designers around the world and has set up a blog with thoughts, sketches and ideas for his dream city. Jason says that his blog is “Like an ever-changing profile of who I am; it’s where people can see what I am like and follow my interests.” Jason loves T-shirts, particularly those from 5Preview in Italy – “they sell cool, one-off printed Ts, and British brands, To-orist and Tom Wolfe.” Jason’s passion for architecture translates into a respect for product that is well designed but understated, like a good pair of jeans from Prps, Flat Head, Dr. Denim, Acne or Levi’s Red – BUT he can’t always afford them unless they are on sale, so sometimes it’s down to the charity shop to find something quirky, or a trip to Primark if he is feeling cheap. Jason always pays in cash when he goes shopping for clothes, “If you haven’t got it [money], don’t buy it.” He uses his credit card only when purchasing online. Jason’s money goes on his car, rent, going to gigs and clubs, and topping up his mobile phone. At the start of term he spent £180 on a bus pass and £150 on gym membership. Rent is £70 per week and food about £40. Jason spends more on clothes than he used to because now he constantly goes out to clubs in Manchester. “With club culture you have to wear something different every time. I’ll go out and spend £300 on clothes in one go and then won’t shop again for three months or so – unless something catches my eye.”

Photographs showing three of the young men interviewed by James Hayes during his customer research investigations. James discovered there was a gap between the brands his target group aspired to wear and those that they actually bought. Aspirational brands were Paul Smith, Comme des Garçons, Diesel Black Gold and Dsquared². Labels actually worn were Zara men, Primark, charity shop clothes, Topman, Levi’s and Jack Wills. It is important to point out that although James focused on young men aged 20 or 21, the potential market for the Sliced Bread concept is likely to extend to customers aged 30, so extra research into customers of this age bracket should also be carried out.

Understanding business customers

Understanding business customers is also extremely important. In B2B situations it is normal procedure for a business to analyse its customer base. This is done for two main reasons – firstly to determine how valuable each customer is to the business, and secondly to understand how best to meet customer needs and service them effectively. In order to fully understand the needs of business customers, it also makes sense to have good knowledge of their end-consumers as well.

Take, for example, an independent designer with their own fashion label who supplies their collection to approximately 40 stores worldwide. They could analyse and classify their customers by country or region, such as Europe, Asia and North America, particularly if end-consumers in each region have differing requirements. The designer may supply independent boutiques that order small quantities from a limited selection of the range, or much larger retailers that take a greater proportion of the collection; so they might want to analyse these customers by the amount they order or by the type of product they order. They may have customers that require little effort to service whereas other customers may have input into the design process, specifying particular colours, styles or fabrics suitable for their end-consumers, and they may require exclusivity, requesting certain styles be made available only to them. These customers might be of great value to the business even though they require a higher level of service.

B2B customers might be assessed by their financial contribution, but there are other assets of value to consider, such as status and reputation of the customer, publicity potential, partnership or networking possibilities, or their ability to provide access to other organizations. In reverse, large high-street retailers usually analyse their supply base so that they can determine which suppliers provide the best service, quality and prices. A large business like a textile manufacturer, for example, might segment its customers by the type of market they represent; separating the companies that purchase for the high-street multiples from other clients who might be at couture or designer level. Below is a summary of criteria to consider when analysing business customers:

•Location – local, national, international or global

•Financial contribution – how much they contribute to turnover and profit

•Reputation – the value attached to their name, type of end-consumer they attract and publicity potential

•Status – new start-up or well established, length of business relationship. Loyalty of custom. Financial security.

•Type of company – department store, independent boutique, retail chain. Or manufacturer, producer or designer.

•Market level – a fabric supplier, for example, may have customers at couture and designer level, as well as retailers that develop own-brand collections.