Because of the expensive 23 November 1866, diplomatic cable to John Bigelow in Paris, Secretary William Seward promptly discontinued use of the old Monroe Code and "set to work as early and prosecuted as vigorously as possible the construction of a new and frugal cipher code. . . ."[265] As explained in the State Department introduction to this new code, the magnetic telegraph required the sender to translate code numbers into letters since numerical signs could not be transmitted. Thus, it happened that fifteen to twenty letters were necessary to express a single letter of the old Monroe Code. A determined and chastened Seward wanted a much more economical system for his secret dispatches.

The newly designed code of 1867, based upon the letters of the alphabet and the frequency of the most common words in the English language, often turned into an awkward communications mask for telegraphers and code clerks, as well as diplomats. Designed for frugality, the code required telegraphers to maintain extremely precise spacing between encrypted groups. Although the code appeared efficient and secret in design, it was awkward to use for telegrams and cables, and caused numerous problems for department and legation clerks during the next eight years.

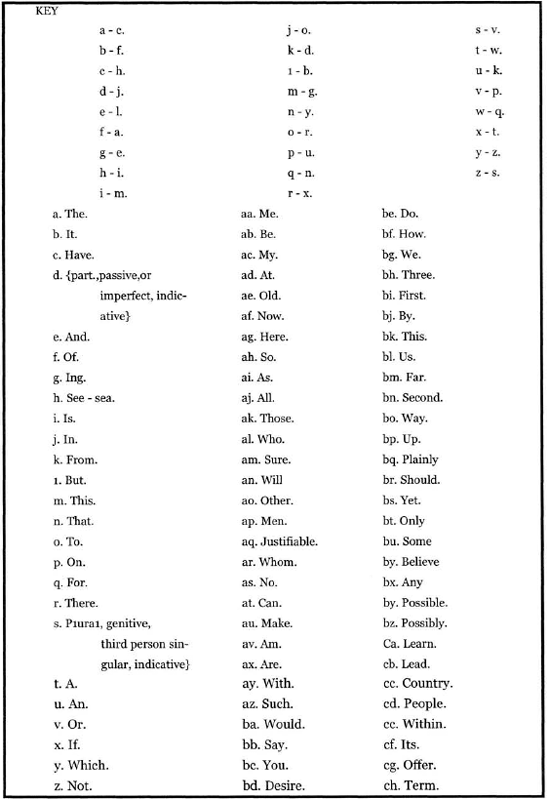

In this code of 148 printed pages, twenty-three words that were the most frequently used in dispatches were assigned one letter of the alphabet. Two other single letters of the alphabet expressed verb tense and plural or genitive third person singular. The letter "w" was not used, except in a cipher table, because it is not used in European languages of a Latin origin and thus would puzzle telegraph operators in those language areas.

The next most common 624 words were assigned two letters of the alphabet; three letters for the remainder of the vocabulary required for common diplomatic usage; and a fourth letter was added for plurals and certain parts of verbs. Code symbols were also prepared for the principal countries and cities in the world, for states, major cities, and territories of the United States, and for proper names of men in English. A cipher table was to be used for those words or names not in the code list.

The first seventy-four pages of the code was the encode portion, and it contained the words in alphabetical order together with the code symbols; for example, the very first word was Aaron with its symbol "aba"; the last word on the first page was acknowledge with symbol "ea." To decode a dispatch was a very frustrating and time-consuming task since the three-letter symbols were published in several sequential alphabetical orders. Hence, one had to search through different sections for the plaintext word. This code, designed for economy and cables, did not please telegraphers and code clerks.

More importantly, transmission of the code by cable proved awkward since there was not a standard number of code characters, and sometimes encoded elements were run together by telegraphers. For example, code elements "a" for the and "k" for from might be run together in the cable and appear as "ak," which meant those. American diplomats often transmitted their urgent and secret dispatches by cable. In addition, they also sent them by post, and frequently the State Department could not decode the cable passages until the postal dispatch arrived because of telegraphers' mistakes in spacing the code letter elements.

The transmission problems became so serious that William Seward wrote to the secretary of the Anglo-American Telegraph Company six months after issuing the code and complained about telegrapher mistakes in transmitting encrypted dispatches. He thought there were no problems in the transmission on the route between Washington, D.C., and Hearf's Content, Newfoundland; however, between there and Valentia, Ireland, there had been frequent and important errors. Unaware that the code design invited transmission errors, Seward wrote, "This cannot be ascribed to any complication in the cipher itself, for as that is composed of letters of the alphabet only. . ." but rather was due to telegraphers.[266] And he noted the multiple errors in a recent cable from the State Department to the United States minister at Copenhagen in which code elements were merged. Seward concluded angrily, "Such a result is certainly not calculated to inspire confidence in your medium of communication."

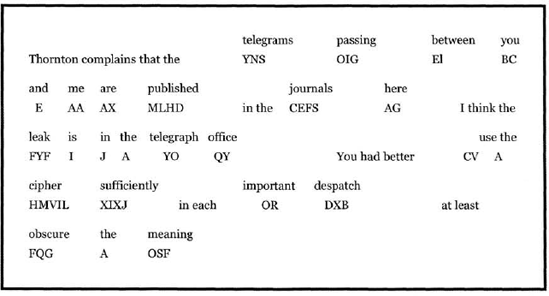

The new code masked communications between the State Department and American legations overseas not only to forestall foreign intelligence agents but also to protect dispatches from domestic interception. Thus, Secretary Hamilton Fish wrote the following dispatch to American diplomat Robert Schenck in London in 1872:[267]

This thrifty complex code, designed primarily for economy, caused many frustrations for the State Department and the ministers because of mistakes by telegraphers during transmission. Foreign codebreakers must also have been baffled as they sought to decrypt intercepted American dispatches. A State Department clerk and future codemaker, John Haswell, recalled those serious problems in a letter to Hamilton Fish: "It will not perhaps have escaped your recollection, that the first cipher message as received at the Department from our minister to Turkey formed one long string of connected letters, which for a time was considered by many in the Department as a conundrum, but finally, after considerable labor was deciphered by Mr. Davis." In fact, Haswell added, "A telegram was received in a similar condition from Paris, and also one from Vienna..." and the latter one was never deciphered.[268] Numerous other such encoded dispatches, beginning in the first months after August 1867, may be found in State Department files.[269] Despite the thoroughly defective design, this State Department code would be used until 1876.

Figure 18.2. Surprisingly, this defective code would be employed by the State Department until the Cipher of 1876, the Red Cipher, replaced Seward's frugal creation.

[265] Deposition of William Seward, 27 July 1870, Records of the U.S. Court of Claims, General Jurisdiction Case Files, 1855–1937, Case No. 6151, Record Group 123, Box No. 307, National Archives.

[266] Seward to John C. Deane, Washington, D.C., 16 January 1868, Record Group 59, Microcopy 40, Roll 63, National Archives. Hereafter cited as RG 59, M40, R63, NA.

[267] Fish to Schenck, Washington, D.C., 16 June 1872, Letter Copy Book, 13 March 1871 to 25 November 1872, Fish Papers, Library of Congress. Sir Edward Thornton was the British minister in Washington, D.C.

[268] Haswell to Fish, Washington, D.C., 8 July 1873, Microcopy, Roll 95, ibid.

[269] For example, Seward to Cassius Clay, Washington, D.C., 30 December 1867, RG 59, M77, R 137, NA. Also, J.C.B. Davis to Fish, Washington, D.C., 16 August 1869, RG 59, E 209, Telegrams sent by the Department of State: many other telegrams in the 1867 code are located in this file.