"The story told today by the translation of captured cipher dispatches is not a pleasant one for any American to read," reported a Republican newspaper, the New York Daily Tribune, on 8 October 1878. "It is a story of such disgrace and shame that we might well wish that events had not rendered its telling necessary. Every citizen must feel that it would have been better for the good name of the Republic had the contest of 1876, with all its intense passions and its crimes, been permitted to pass from memory." Directed by its famous and especially aggressive editor, Whitelaw Reid, the Tribune's journalistic crusade against alleged political corruption by the Democrats sought to uncover the massive electioneering corruption masked in encoded political telegrams. And the daily newspaper would highlight on its front pages all the scandalous maneuvering by leading Democrats during the election of 1876.

Especially targeted were all the encoded messages sent and received by Samuel Tilden's major political advisors and confidants, and maybe even by Tilden himself, at Democratic National Headquarters in New York City. Eagerly judgmental, the Tribune proclaimed on 10 September, "It is correspondence in secret cipher – the language familiar to conspirators in crime who dare not face the daylight. Portions translated prove that agents were instructed to buy an electoral vote, and furnished with money to pay for it. Other parts, not yet deciphered, obviously refer to money transactions in immediate connection with the action of returning and canvassing boards and electors at the South."[272]

A few days earlier, the angry Republican editors, reflecting American uneasiness with secrecy, noted that the dispatches were not in the "everyday English of honest men." Moreover, "the very fact that secret ciphers had been arranged before these confidential agents went out indicates that communication was expected of a character which it would not be safe to have known, even to telegraphic operators bound to secrecy."[273] The irate editors made no mention of merchants, bankers, foreign diplomats, and journalists, who also used ciphers and codes to protect their confidential messages in the communications world of telegraphs and cables during peacetime.[274] Codes and ciphers were required for secure communi-cations because intrigues, collusion, and cabals colored presidential politics at that time. Indeed, politics balanced on the edge between war and peace.

How and why did this newspaper political firestorm about secret messages begin? Who were the major participants? Was one political party more corrupt than the other? Was the nation, weak, divided, and more susceptible to dishonest politicians because of the chaotic conditions created by the Civil War and Reconstruction?

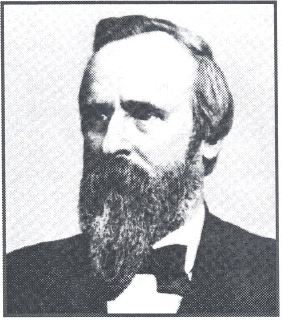

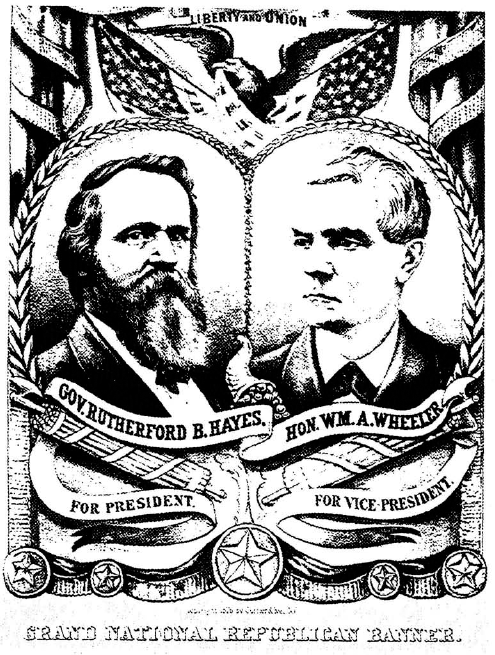

The presidential election of 7 November 1876, considered the most openly corrupt contest up to that time, found two state governors as candidates: the famous New York reformer of political graft and corruption, Samuel J. Tilden, a Democrat; and Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio, a Republican, major general of volunteers in the Civil War, former member of Congress, thrice elected as governor – a conscientious leader who pressed for social improvements in the prison system, mental hospitals, and state education. Fifty-three years old, an extremely able administrator, Hayes also gained a modest national reputation as a reformer.

From election returns on 8 November, many persons believed that Tilden had 184 electoral votes, one short of a majority. However, a Republican newspaper, the New York Daily Tribune, reported that Tilden had 188 votes, 141 for Hayes, and 34 undecided. When the Tribune's pugnacious editor, Whitelaw Reid, learned that the Republican New York Times had printed a different set of figures giving Tilden less than a majority of the votes, and reported the race as undecided, a delighted Reid quickly reprinted the Times's analysis the following day.[275] Hayes had unquestioned control of 166 electoral votes. In the disputed electoral column were the eight electoral votes of Louisiana, seven of South Carolina, and four of Florida. These were the final three states in which Republican regimes remained strengthened by the votes of blacks. Hayes had carried Oregon; however, the governor of that state, a Democrat, might name a Democrat as a substitute for a Hayes elector because the Republican elector was ineligible to serve since he was a federal officeholder, a postmaster. In the national popular vote, Tilden led his opponent 4,288,546 to 4,034,311.

During the four weeks after 7 November, each political party fought fiercely to ensure victory for its presidential candidate. Because of Reconstruction, a Republican administration, aided by federal troops, dominated the three Southern states and thus hoped to regulate those state Returning Boards that reviewed the election returns for ineligible voters. A majority of the board members were Republican. Could enough Tilden votes be eliminated to award the states to Hayes? Historian C. Vann Woodward argues that both parties employed "irregularities, fraud, intimidation, and violence" during the election.[276] Bitterness and duplicity highlighted this presidential election. As a brilliant team of American historians, Charles and Mary Beard, judged, "By both sides, frauds were probably committed – or at least irregularities so glaring that long afterwards a student of the affair who combined wit with research came to the dispassionate conclusion that the Democrats stole the election in the first place and then the Republicans stole it back."[277]

In the days immediately following the election, representatives of the Democratic and Republican parties went into the three Southern states. These "Visiting Statesmen" maneuvered to bring about or ensure their candidate's victory. And it is during these weeks that the broad flood of cipher telegrams from the Democratic visiting statesmen such as Smith Reed and Manton Marble, former editor and owner of the New York World, inundated their New York headquarters. These encrypted documents would later undergo public scrutiny in the congressional investigations.

On 6 December, the Republican electors in the three Southern states met in their capitals and voted for Hayes; Democratic electors also met and cast their votes for Tilden. The Congress was divided on which set of votes to recognize. According to the Constitution, the president of the Senate (then a Republican pro tern) shall open the votes in the presence of the Senate and the House of Representatives; however, the Constitution is silent on whether he or the members of Congress (then predominantly Democratic), acting jointly, should rule on disputed votes. If the Senate president decided on the disputed votes, the Republicans would win; however, if disputed votes were not counted, then neither candidate had a majority, and election would go into the House of Representatives – as it had in 1801 and 1825 - which had a Democratic majority. In addition, if no decision were reached by 4 March, the vice president was to become acting president; however, this office had been vacant since the death of Henry Wilson. The remaining days of December and the first two months of 1877 heightened the dreadful anxieties about the nation's competence to decide on the competing and angry claims to the presidency.

Fortunately for the nation, on 18 January a compromise was achieved and a bill passed that established a fifteen-member electoral commission. The commission would make the final judgment on electoral votes, and it was hoped that this would prevent an armed conflict involving federal troops, national guard units under the control of Democratic governors, and tens of thousands of ex-Union soldiers. As an astute scholar correctly observed, creation of the electoral commission was one of the wisest pieces of statecraft ever evolved by an American Congress.[278] And the real heroes working for the compromise were President Ulysses Grant, Senators George Edmunds, Allen Thurman, Thomas Bayard, Representative George Hoar, and Congressman Abram Hewitt, who also served as chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

Even before the commission deliberated during February on returns for Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, Republican agents were in contact with Southern Democrats whose first priority focused on restoration of white power in these states, including withdrawal of federal troops from the Southern states. This objective outweighed the Southern Democrats' quest for the presidency. Quietly, Hayes and his associates assured Southern Democrats that a Republican president would be supportive of their immediate goals.

Beginning on 1 February 1877, each state's electoral vote was tallied in each house of Congress. By an 8–7 vote, the commission awarded Florida to Hayes, and before the month was over, all disputed electors went to Hayes. (In the future, Hayes would be known to his critics as old "Eight to Seven.") Hayes' party leaders were able to prevent a Democratic filibuster in the Congress by promising to remove federal troops from the South, to promote Southern internal improvements, especially a railroad linking the South to the West Coast, and to appoint a Southern leader to his cabinet.

Thus, the electoral vote count was completed at 4 a.m. on 2 March with Hayes receiving 185 votes to Tilden's 184 in the last hours of President Grant's second administration. Hayes took the oath of office privately the evening of 3 March and publicly on 5 March. But many angry Democrats rejected the commission's vote, and on 3 March House Democrats passed a resolution declaring Tilden had been "duly elected president of the United States for the term of four years, commencing on the 4th day of March, A.D. 1877."[279] Clearly, the divided nation and political parties remained on the edge of further turmoil.

Months before the commission voted, the Western Union Telegraph Company had ordered its employees to send to its New York office all dispatches and copies of dispatches relating to the presidential election of 1876. Eager to demonstrate its dedication to maintaining the security of its communications service, the company planned this maneuver to keep the more than 30,000 telegrams, many in cipher, out of the reach of the Congress and publication. They were placed in the care of the company attorney, who would be less likely to be called upon to produce these documents than the other officers of the company.[280] Later, the maneuver failed when the Committee of the House of Representatives on Louisiana Affairs, headed by Democrat W. R. Morrison, called for the Louisiana dispatches. In addition, the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections requested the Oregon dispatches, numbering 241. The remaining 29, 275 dispatches were placed in a trunk and given to the care of the manager of the Washington Western Union office.[281]

The Committee on Privileges and Elections, under the chairmanship of Oliver P. Morton, the Republican senator from Indiana,[282] began taking testimony regarding the electoral votes of certain states in late December 1876 from representatives from New Jersey, Missouri, Minnesota, Oregon, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida. The most dedicated committee member was Morton, who, quite naturally, believed the Republicans had won the election. Indeed, after the presidency had been decided, he made a commitment to root out political corruption throughout the entire nation! Later, he traveled west to Oregon to investigate charges of dishonesty against a newly elected senator from Oregon, and while there suffered a stroke in August and died the following November.

As contradictory and highly charged testimony before the Senate committee continued, one aspect of the inquiry came to focus on the Oregon electoral controversy. Right after the election, while the Oregon electoral votes were being disputed, Dr. George L. Miller, editor of the Omaha Herald, an aggressive campaigner and member of the National Democratic Committee and close friend of Samuel J. Tilden, was asked by Colonel William T. Pelton of the Democratic National Committee in New York to investigate the Oregon situation in person. Miller, unable to take on this mission, sent a colleague, Mr. J.N.H. Patrick, a lawyer, businessman and zealous Democrat, to see Governor L. F. Graver in Salem, Oregon. Purpose: to acquire one more electoral vote in Oregon.[283]

Before Patrick left Omaha, he and Miller arranged a dictionary code message system. In testimony before the committee, a cautious Miller would not reveal the book's name and noted only that it was small. Moreover, he reported that a memo contained the system for using the dictionary, and without it and the book, he was powerless to explain the system further to the committee. Additional questioning of Miller proved fruitless since Miller, without the dictionary and memo, could not or would not decode the mysterious telegrams shown him by the committee. He testified he had left the dictionary book back in Omaha!

A subpoena by the Senate committee calling for the Oregon dispatches was issued in the latter days of January 1877, and the mysteries of encrypted telegrams, soon to be publicized in the newspapers, would fascinate an anxious and uncertain nation.

These telegrams showed the Democrats employed an exceptional code to veil their hundreds of telegraphic dispatches to Oregon during November and early December. Accounts of the mysterious encoded "Gabble" telegram sent to Tilden on l December 1876 from Portland, Oregon, surfaced in the Detroit Tribune in early February 1877 and were picked up by the New York Times on 8 February.

Incidentally, Republican agents and managers also used a few codes during the exciting days and weeks surrounding the hectic presidential election; however, the few encoded dispatches that surfaced reveal codes of little importance and of simple character. For example, one of the Republican managers, William E. Chandler, a graduate of Harvard Law School and national committeeman from New Hampshire, played a key role in directing strategy during the 1876 presidential campaign. Chandler made only a modest effort to mask a dispatch from Florida:

Noyes and Kasson will be here on Monday, and Robinson must go immediately to Philadelphia, and then come here. Can we also have Jones again? Rainy for not more than one tenth of Smith's warm apples. You can imagine what the cold fellows are doing.

Only five words or phrases were in code: "Robinson" called for $3,000 to be deposited in Philadelphia; "Jones" was $2,000; "Rainy" meant favorable prospects; Smith's "warm apples" actually meant a 250 majority; and "cold fellows" were the opposition Democrats.[284]

Angry Democrats charged that there were few encoded Republican telegrams because William Orton, an avid Republican and the seventy-year-old president of Western Union, permitted party associates to extract some of these telegrams before turning them over to the committee. One scholar complained, "If all the telegrams had been known, it seems probable that Republicans would have been quite as much compromised as Democrats."[285]

The New York Times' editor wrote on 8 February that "Gabble" was a code word for Grover, Oregon's governor, and with humor he explained further that "The Tribune has also discovered that where the word 'medicine' is used in Patrick's dispatch it should be translated 'money,' and it may reasonably be inferred that 'Gabble' was a person who could take in a good deal of medicine. In this case it seems to have been prescribed from what the physicians call its "alternative qualities."

In welcome testimony before the elections committee, William Stocking, managing editor of the Detroit Post stated that Alfred Shaw came into his office and said he had a translation of the encoded "Gabble" dispatch that he had seen in the Detroit newspapers. With the dictionary, Shaw showed the editor the system for decoding the dispatch.[286] Editor Stocking also paged through the dictionary and confirmed Shaw's findings. Delighted that the Detroit newspaper had publicized the pocket dictionary that supplied the key to the encoded telegrams, the New York Times added that the key revealed the following startling information: "The Governor of Oregon informs Tilden five days before he gave his decision that he will decide every point in the case of Post Office Elector in favor of the highest Democratic Elector (E. A. Cronin) and that the certificate will be granted accordingly."[287] The substance of the mysterious Gabble telegram had now been published.

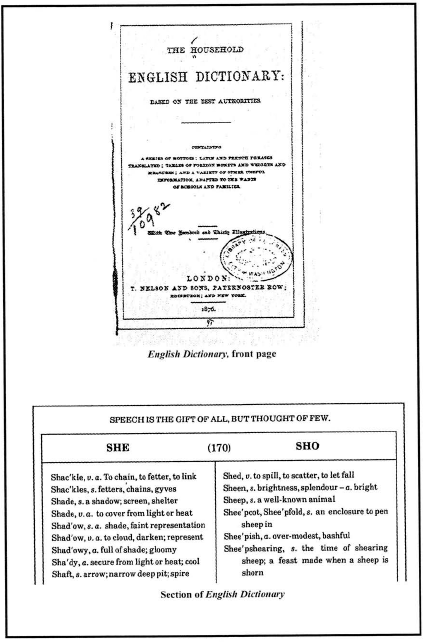

On the evening of 14 February the committee summoned Alfred B. Hinman, an oil merchant from Detroit, who had had previous business dealings with J.N.H. Patrick. He finally revealed that he had exchanged a code system for telegraph messages with Patrick in the summer of 1874 for their private business matters that was based upon the book The Household English Dictionary. Based on the best authorities, published in Edinburgh and New York in 1872,[288] this small volume, measuring four inches wide by six inches high, and 3/4 inch thick, contains 241 pages; each page, including those containing sketches of animals or other objects, has two columns.

The most enlightening testimony came from Hinman's general agent and oil merchant, Mr. Alfred W. Shaw, who was most familiar with the system employed by Patrick and Hinman. Moreover, Shaw had already decoded the dispatches that passed back and forth between Democratic committee members in Portland, Oregon, and New York City. Shaw was then asked by the committee to decode the Gabble message below in the presence of the committee:

According to Shaw, who learned the system by trial and error, the key to decoding the Oregon dispatches is as follows: take the word in the dispatch, find it on the proper page and column in the dictionary. Then in the list of words in the column, count the number of words from the top of the page down to the encoded word; and then go forward eight columns (there were two columns per page). In the eighth column, count down the same number of words and you arrive at the plaintext word.[289] Shaw pointed out several exceptions to this rule: the words of and highest do not appear in the dictionary; therefore, they are plaintext words. In addition, the word "accordingly" is also used as it stands because it was customary to use only proper words in these telegrams. Also plaintext words that appear in the first eight columns, such as "a," "act," and "action," are not encoded since they were in the first pages of the dictionary, and therefore the sender could not turn back the necessary eight columns.[290] Shaw said the word "Gabble" means governor, and he learned this from using the different dispatches wherein the word "governor" is the only one that makes sense.

Note

December 1st, 1876

To Hon Samuel J. Tilden, No. 15 Gramercy Park, New York:

Heed scantiness cramp emerge peroration hot-house survivor browse of piamater doltish hot-house exactness of survivor highest cunning doltish afar galvanic survivor by accordingly neglectful merciless of senator incongruent coalesce.

GABBLE

Shaw said the encoded Gabble message reads

I shall decide every point in the case of post-office elector in favor of the highest democrat elector, and grant the certificate accordingly on morning of sixth instant. Confidential

Governor[291]

Three of the most interesting encoded telegrams, all of them sent to Tilden's nephew, Colonel Pelton, sent from Oregon and decoded by Shaw, read in plain text as follows:

To W. T. Pelton, Portland, Nov. 28th 1876

No. 15 Gramercy Park, New York:

Certificate will be issue to one democrat; must purchase republican elector to recognize and act with democrat and secure vote and prevent trouble. Deposit ten thousand dollar by credit Kountze Brother, 12 Wall street. Answer.

J. N. H. Patrick[292]

To W. T. Pelton, Portland, Oregon, November30

No. 15 Gramercy Park, New York:

Governor all right without reward. Will issue certificate Tuesday. This is a secret. Republicans threaten, if certificate issue, to ignore democrat claim and fill vacancy, thus defeat action of governor. One elector must be paid to recognize democrat, to secure majority. Have employ three, editor only republican paper, as lawyer. Fee, three thousand. Will take five thousand for republican elector. Must raise money; can't make fee contingent. Sail Saturday. Kelly and Bellinger will act. Communicate them. Must act prompt.[293]

Portland, December 1, 1876.

W. T. Pelton, No. 15 Gramercy Park, New York: No time to convene legislature. Can manage with four thousand at present. Must have it Monday certain. Have Charles Dimon, one hundred and fifteen Liberty street, telegraph it to Busk, banker, Salem. This will secure democrat vote. All are at work here. Can't fail. Can do no more. Sail morning. Answer Kelly in cipher.[294]

Although Shaw decoded sixteen of the telegrams relating to the Oregon dispute word by word in the presence of the committee, certain skeptical senators still questioned the system he used![295]

The Democratic practice of encoding the election dispatches for purposes of secrecy was understandable since their plaintext dispatches often displayed confidential strategies and threatened armed resistance tactics in the bitter political campaign for the presidency. For example, General John M. Corse, an authentic Civil War hero and chairman of the Cook County Democratic Committee in Chicago, sent the following dispatches in plain text (he did not have a code):

To CoL W. T. Pelton, New York, December 6

Glory to God. Hold on to the one electoral vote in Oregon. I have 100,000 men to back it up.[296]

To W. T. Pelton, Everett House, New York:

I have no objections to going, but it will take ten days. That will be too long. Can't you send somebody from San Francisco. Just rec'd telegram from Gov. Palmer that vote of Louisiana will be counted for Tilden. Hurrah.[297]

Gen. John M. Corse, Palmer House: New York, November 21

If you think it necessary you can pay National Democrat [Chicago German newspaper] two hundred and draw on me sight, and thus close it.

W. T. Pelton[298]

Chicago German newspaper

Another active Democrat and successful banker in Chicago, W. F. Coolbaugh, sent this distressing telegram in plain text on 14 November to the Democratic leader investigating voting in Louisiana:

To Hon. Lyman Trumbull, St. Charles Hotel, New Orleans:

Should Louisiana republican officials fraudulently change vote, let representative democrats there telegraph governor of Oregon to withhold certificates of election to Hayes electors, and thus protect the people. Telegraph me outlook immediately.[299]

November 15, 1876

Perry H. Smith, Saint Charles Hotel, New Orleans, La.

If Louisiana electoral vote is stolen from us, we will get California and Oregon. We have one hundred and sixty thousand ex-soldiers now enrolled. Vast number of republicans with us. Stand firm.

Corse[300]

Daniel Cameron, the private secretary of Cyrus H. MCormick, chairman of the State Central Committee of Illinois, joined Corse in sending the following plaintext dispatch to General John M. Palmer, who was also examining Louisiana election returns:

Two hundred thousand ex-Union soldiers, embracing thousands who voted Hayes, sustain you. If Tilden is fraudulently counted out in Louisiana, the end is not yet. You have Illinois behind you.[301]

The chairman of the Democratic National Committee, Abram S. Hewitt, testified to the committee that he was not familiar with The Household Dictionary; however, he did explain that in his business he used a cipher dictionary in which he found a five-digit number opposite the plaintext word, and then he added or subtracted from that number in an amount agreed to with his correspondent. Very likely he was using Robert Shaw's Telegraphic Code.[302] Moreover, he added he had not sent a single encoded dispatch during the whole presidential campaign.

W. T. Pelton, Tilden's nephew, who lived at the Tilden residence at 15 Gramercy Park and managed the National Committee office, suffered many amazing lapses of memory before the Senate committee about whether The Household Dictionary was the key for the encoded dispatches. He testified that, for the most part, the dispatches were decoded by staff members. He also swore that Governor Tilden never saw the encoded dispatches. When questioned further, Pelton admitted that since the election he had purchased numerous copies of Slater's Code, presumably for business purposes.[303] Pelton replied to dozens of questions about encoded telegrams, either sent or received by saying "I do not remember." Without question, Pelton sat at the nerve center at 15 Gramercy Park and Democratic National Headquarters: it is possible that he or Manton Marble designed or ordered the various complicated code systems for confidential communications between the various Democratic managers in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina for their messages back to New York. After Pelton's appearance, the hearings ended on 28 February with over 500 pages of testimony. And, two days later, as noted earlier, the electoral commission determined Hayes had 185 votes.

Tensions about the election persisted for some time as Northern Democrats, including Samuel Tilden, continued to cry "Fraud" when recalling the 1876 election results. Bitter accusations and continuing calls for investigation echoed throughout Congress and the nation.

In the fall of 1878 (two months before the congressional elections), the New York Daily Tribune launched a new and at times vicious attack on Governor Tilden, the Democratic party, and their alleged failed attempts to "buy" the election of 1876. The Tribune stated that Democratic agents, in seeking electoral votes, offered bribes of $50,000 in Florida, $100,000 in South Carolina, and actually paid $3,000 in Oregon.[304] Packets of encoded Democratic telegrams were sent anonymously to editor Whitelaw Reid during the summer months. These telegrams were part of the 30,000 that had been subpoenaed in early 1877 by the House and Senate committees and later, it was believed, returned to the Western Union Company and destroyed by burning. In fact, however, a large number of the dispatches had been abstracted while in the custody of the Morton committee, and many of them, along with some original telegrams, were eventually given to Reid. The secretary of the National Republican Committee, William E. Chandler, also provided additional copies. The total number exceeded 700 telegrams. Democratic critics would charge that unscrupulous Republicans not only provided the dispatches but also destroyed Republican telegrams that might damage Republican reputations.[305]

The Tribune eagerly took up the challenge of investigating these dispatches, which originated in Florida, South Carolina, and Oregon. "The Oregon story is so good an illustration of the insincerity of Democratic professions and the rascality of Democratic practices that it is well worth while to repeat it," wrote the editors. "We have gone through the whole of the vast pile of telegrams relating to this matter – some hundreds in all – and have translated a number of cipher messages that have never before been explained, besides correcting several others which have been imperfectly interpreted." Headlines for the story denounced the "Oregon Fraud: A Full History of the Tilden Plot, How the Democratic Reformer Attempted to Purchase a Majority of the Electoral College – The Cipher Dispatches."[306] This edition and several subsequent ones reprinted copies of the encoded and decoded telegrams on the "Tilden Plot" in Oregon.

One month later, the Tribune covered its front pages with another installment of what it termed "The Tilden Ciphers" under a two-column lead, "The Captured Cipher Telegrams." And in an editorial under the heading "The Secret History of 1876," the editors claimed, with some exaggeration, "The most ingenious and intricate system of ciphers yet known was devised in order to conduct the negotiations." The various Democratic cryptographic systems provided concealment far superior to most earlier American cryptographic designs with a major exception: Jefferson's cipher wheel.

The New York Daily Tribune's energetic Whitelaw Reid, then forty years old and an ardent Republican, joined the Tribune staff in 1868, and became managing editor the following year. Publishing literary contributions from Mark Twain, Bret Harte, and Richard Henry Stoddard, together with improved foreign news coverage, and comprehensive reporting on the Whiskey Ring scandal, and overthrow of the Canal Ring, increased the circulation and national influence of this daily newspaper. By 1876, the Tribune boasted 60,000 readers, mainly conservative, middle and upper class.[307] Though the paper supported Tilden as governor of New York in 1874, it backed Hayes in the 1876 presidential election.

For Reid, the Democratic telegrams provided a marvelous journalistic challenge and a welcome opportunity to weaken the Democratic party. Fortunately, he found a brilliant staff member to investigate the difficult codes. That member would become one of the Tribune's successful code-breakers, one of a fascinating trio of brilliant United States codebreakers, probably the most famous cryptographic experts in nineteenth century America: John Hassard, William Grosvenor, and Edward Holden.

John Rose Greene Hassard, then forty-two years old, was a graduate of the Jesuit's St. John's College, Fordham, obtaining both bachelor's and master's degrees. Writing for the New American Cyclopaedia, some reporting for the New York Tribune, and then preparing a First-rate biography on Archbishop John Hughes were a prelude to his brief editorship of the newly founded Catholic World in 1865.

John Rose Greene Hassard, then forty-two years old, also hungered for political reform at both the municipal and national levels. Hassard would argue that telegraphic cipher appeared to be necessary in all important political campaigns. And then he added an appealing but rather impractical idea: "It would hasten the Reform millennium, however, if such messages — being in no right sense of the word private telegrams, but a part of the apparatus of popular elections – could always be collected by Congress after the close of the contest, and exposed to public view, on the ground that the people ought to know exactly how their business has been conducted."[308] He found the Tilden cipher dispatches an attractive and demanding problem. And he plunged into the mysteries of masked messages.[309]

Fortunately, Reid and Hassard found another staff person, the Tribune's economic editor, Colonel William Mason Grosvenor, who also delighted in solving challenging problems. The same age as Hassard, Grosvenor had been editor of New Haven's Journal-Courier, followed by stints as editor of the St. Louis Democrat and manager of reformer Carl Schurz's successful campaign for the United States Senate.[310]

When questioned by Potter's Select Committee on Alleged Frauds in the Presidential Election of 1876, Reid testified that both Hassard and Grosvenor "worked very industriously and zealously" on the enciphered dispatches. "Mr. Hassard, however, did the largest part of the work. He was the earliest in the field and the latest. Both of them did exceedingly good work."[311] And both of them worked independently!

Noting there were no fewer than six distinct systems of cryptography in the secret telegrams, the Tribune focused on the scandalous history of the electoral campaign after the election of 1876. Their review of the political correspondence covered almost 400 telegrams, of which about one-half were in plain text and the others in code, between Democratic managers in New York and their secret agents and friends in California, Oregon, Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Their description of the Oregon telegrams described the system for decoding these mysterious messages by employing, as they term it, "The Little Dictionary," which in actuality was The Household English Dictionary noted above. It is interesting to note that the Tribune did not credit the significant contributions of Alfred Shaw in explaining the code system for the Oregon telegrams.[312]

Another code system, used in the Southern telegrams, provided greater challenges, a pattern of what the editors termed a cipher within a cipher. In reviewing the Southern telegrams, the Tribune team noted there were no words for "Democrat" or "Tilden" or "President" or "Hayes" or "Telegram," and they suspected geographical proper names were substituted for these names and other expressions. Their first break came when they focused on the word "Warsaw," which frequently appeared in most of the longer dispatches and in one message appeared all by itself. They suspected it might mean telegraph, and this as confirmed when they worked on the following telegram:

With help from the word "telegram," they determined the words in the dispatch should be ordered according to the following sequence: 9,3,6,1,10,5,2,7,4,8. Their progression was proved correct when they applied the distribution order to many other ten-word telegrams and discovered they could also read them.[313] However, some ten-word telegrams did not translate well with this sequence, and, after trial and error, they discovered a second sequence for other ten-word telegrams: 4,7,2,9,6,3,8,10,1,5. Hassard and Grosvenor provided pages upon pages of decoded dispatches to the Tribune.

Another brilliant individual, Professor Edward S. Holden, a mathematician,[314] was chosen by Potter's Select Committee in late January 1879 to examine all the campaign dispatches held by the committee and to decipher them. Holden had become fascinated by the novel and ingenious character of the encoded dispatches in early September 1878, and months before he was solicited by the committee. Apparently he approached the Tribune and met with John Hassard, who recalled Reid's desire to seek counsel on the codes from a mathematics professor. Hassard gave Holden several of the dispatches, and later the professor wrote to Hassard about them and requested, perhaps because of his government employment, that his name be kept confidential. According to Reid's testimony, no Holden translations of specific dispatches were received by Hassard or Grosvenor until those dispatches had been decoded by the Tribune executives. There was one exception: Professor Holden did locate one of the dictionaries that had been used by the Democrats shortly before Reid found it.[315] However, it is interesting to note that Hassard, Grosvenor, and Holden consulted and exchanged opinions with one another about particular codes.

Holden's study and report, prepared between 24 January and 21 February 1879, for the committee, included plain text and decoded copies of the Democratic dispatches. He provided a superb analysis and summary of the different code and cipher systems developed by the Democrats in the election of 1876. This collection of codes and ciphers reflects an amazing quest by energetic Democratic leaders seeking electoral votes: the masks also depict ingenious methods by Democrats for maintaining secret communication. And during the many weeks of testimony before the Senate and House committees, the Democratic leaders such as Marble, Pelton, Weed, and others provided no information on their secret codes and ciphers. Only the congressional investigation on the maneuvers involving the Oregon electoral vote provided information on the dictionary key for those encrypted dispatches.[316]

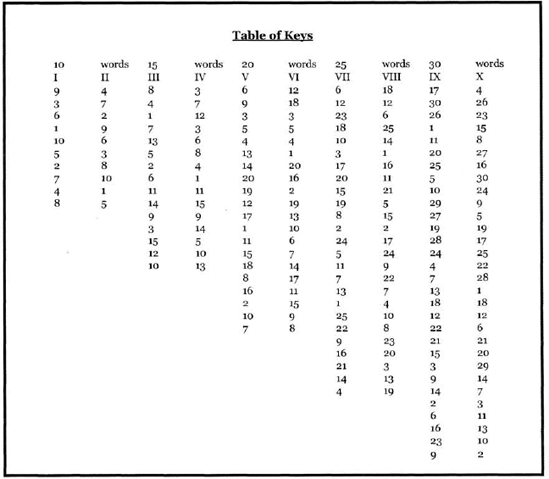

Holden's thorough report began with a description of the sequence keys used by the Democrats and Republicans for their telegrams.[317] The complicated and highly imaginative cryptographic systems solved by Holden are noted below:

There were two different keys for messages of various lengths, and all telegrams were of the segments noted above. In a few instances, the messages were not in a multiple of five words; however, these dispatches probably resulted from mistakes. Moreover, the secret telegrams were transmitted to and received from Democratic representatives in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina as they contacted New York, and the particular code these men used often had application only to the specific state, rather than to the covey of states. Also in contrast to the code vocabulary of numbers and names below, the sequence keys are more definitive and subject to proof than the vocabulary plain text drawn from context and deduction.

Table 20.1. Code Vocabulary for Numbers

Code | Number | Code | Number |

River | 0 | Potomac | 6 |

Rhine | 1 | Schuylkill | 7 |

Moselle | 2 | Mississippi | 8 |

Thames | 3 | Missouri | 9 |

Hudson | 4 | Glasgow | hundred |

Danube | 5 | Edinburgh | thousand |

Table 20.2. Names, Terms

Code | Plaintext | Code | Plaintext |

Africa | Chamberlain | Ithaca | Democrats |

America | Hampton | Lima | acceptable, ed |

Amsterdam | bills[?] | London | canvassing board |

Bolivia | proposal | Louis | governor |

Brazil | too high[?] | Max | John F. Coyle |

Bavaria | probably some | Monroe | county |

Republican official | |||

Bremen | Commissioner[?] | Paris | draw |

Chicago | cost, draft, expense | Petersburg | deposit |

Chili [sicl | cautious[?] | Portugal | some Republican official: possibly Chandler |

Copenhagen | dollars | Rochester | votes |

Denmark | Colonel Pelton | Russia | Til den |

Europe | Louisiana | Syracuse | majority |

Europe | Gov. Kellogg | Utica | fraud |

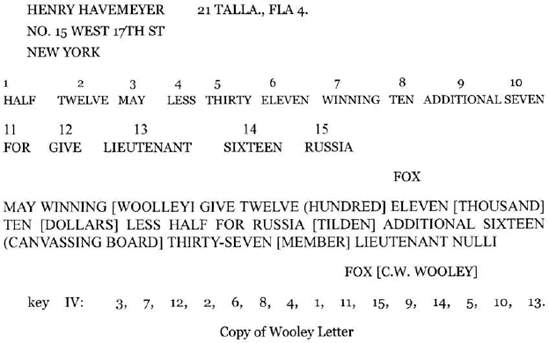

Fox | C.W. Woolley | Vienna | payable[?] |

France | Florida | Warsaw | telegram |

France | Gov. Stearns | Asia | ? |

Greece | Hayes | Dryden | ? |

Havana | Republicans |

These plaintext words were chosen after reviewing hundreds of telegrams: a majority of the terms were developed by the Tribune experts and also found to be in agreement with Holden's translations.

Table 20.3. Dumb Words or "Nulls"

1.Anna | 6..Jones |

2. Captain | 7. Lieutenant |

3. Charles | 8. Thomas |

4. Daniel | 9. William |

5. Jane |

The words above were used to fill out telegrams so the number of words would equal 10, 15, 20, 25, or 30 words so that the proper series noted above could be used.

Number Code

According to Holden, Colonel Grosvenor provided the code noted below. Holden noted the code did not, however, provide a complete plain text for one dispatch.

Code | Plaintext | Code | Plaintext |

|---|---|---|---|

France | Two | Nineteen | Received |

Italy | Three | Twenty | Agree, agreed, agreement |

Greece | Four | Twenty-one | Telegraph |

England | Five | Twenty-three | Edward Cooper |

One | Telegraphic credit | Twenty-four | Vote |

Two | Will deposit | Twenty-seven | J.F. Coyle |

Three | Supply or provide | Thirty | Republicans |

Four | Have you arranged or deposited | Thirty-two | Canvassing |

Five | Will send, or remit | Thirty-four | G.P. Raney |

Seven | Draft or draw | Thirty-five | Requirements |

Nine | Bank | Thirty-seven | Member |

Ten Dollars | Forty | Expenses | |

Eleven | Thousand | Forty-one | Paid or protected, accepted |

Twelve | Hundred | Forty-six | Prompt, or prudent |

Sixteen | Canvassing | Fifty | |

Board |

John Hassard, noted Holden, worked out part of the South Carolina code below:

Code | Plaintext |

|---|---|

Bath | Court |

Cuba | Electoral vote of South Carolina |

Naples | Majority |

January | Democratic |

Jo | Telegraph |

April | Failure |

Chicago | Cost, expense |

The testimony of William E. Chandler revealed that the Republicans- code was indeed modest and also somewhat creative as they termed the Democrats "Cold Fellows!" Holden noted the following list:

Code | Plaintext |

|---|---|

William | Send |

Rainy | Things look favorable |

Robinson | $3,000 |

Jones | $2,000 |

Brown | $1,000? |

Smith | $250? |

Warm apples | Majority |

Cold Fellows | Democrats |

Oranges | Florida |

Cotton | Louisiana |

S.C.cotton | South Carolina |

Dictionary Codes

Holden included another dictionary in addition to The English Household Dictionary. He found that Webster's Pocket Dictionary contained the word "Geodesy," which proved to be the key for decoding four dispatches.

Table 20.4. Double-Number Code

20 | d | 62 | x |

25 | k | 66 | a |

27 | s | 68 | f |

31 | 1 | 75 | b |

33 | n | 77 | g |

34 | w | 82 | i |

39 | P | 84 | c |

42 | r | 87 | v |

44 | h | 89 | y |

48 | t | 93 | e |

52 | u | 96 | m |

55 | o | 99 | j |

Cipher

Cipher n o p q r s t a b c d e f u v w x y z g h i j k l m

English a b e d e f g h i j k i m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

Table 20.5. Other Ciphers

English | Key A | Key B | Key C | Key D | Key E | Key F | Double Letter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

a | n | - | p | l | h | z | yy |

b | o | - | t | - | i | a | ma |

c | p | - | e | o | j | b | ep |

d | q | - | r | n | k | c | it |

e | r | z? | - | c | l | d | ns |

f | s? | - | o | p | m | e | ye |

g | t? | - | n | k | t | f | mm |

h | a | i? | k | y | u | g | pp |

i | b | - | I | v | v | h | ei |

j | c | - | - | - | w | i | - |

k | d | - | q | - | x | j | ia |

e | m? | a | - | y | k | sh | |

m | f | - | b | - | z | 1 | ny |

n | u | - | d | g | a | m | ss |

o | v | w? | c | f | b | n | aa |

p | w | - | f | a | c | o | sn |

q | x? | - | w | - | d | p | - |

r | y | i? | u | d | e | q | pi |

s | z | - | e | f | r | im | |

t | g | - | v | b | g | s | pe |

u | h | c? | z | r | n | t | ai |

v | i | - | i | t | o | u | em |

w | j | - | y | - | p | v | sp |

X | k? | - | s | s | q | w | - |

y | 1 | - | h | u | r | x | en |

z | m | - | - | - | s | y | - |

Key B and Key D above are so fragmentary because only one message was sent in each cipher. Only three messages were sent in Key F; and the Double Letter Key was deduced from the translations given in the New York Daily Tribune.

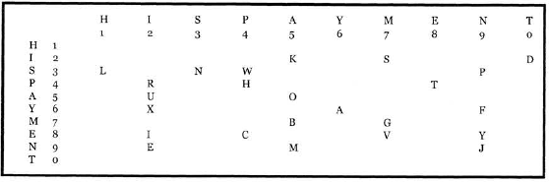

Many years later, the brilliant cryptographer William F. Friedman reconstructed the square upon which the double letter and double number ciphers were based. And the key phrase used by the Democratic agents is most interesting in the light of the charges of bribery! With this square, Friedman also supplied the missing combination for the letter J, which is nn, and X, which is yi. Holden's report did not include those two letters. Q and Z had no ciphers in either solution by Holden or Friedman. The square developed by Friedman is as follows:[318]

Samuel Tilden requested an appearance before the cipher subcommittee of Potter's Select Committee when it was holding its sessions in New York City's Fifth Avenue Hotel in February 1879. Earlier, his associates, Colonel Pelton, Manton Marble, and Smith Weed, had testified about the Democratic involvement with the electoral votes. On the 8th, in a circus-like atmosphere, unruly curiosity seekers, together with officials, politicians, and representatives of the press, clogged the hallway leading to the committee room two hours before Tilden's scheduled appearance. At 11:30, a weak but defiant Tilden appeared, dressed in black, with "an air of great solemnity on his face, which looked as imperturbable and sphinx-like as ever," the New York Herald reported.[319] "Since his last public appearance, he seemed to have aged considerably, and yesterday he looked quite ill and feeble. As he afterward explained, he was suffering from a severe cold. It was, indeed, quite a painful spectacle to see the slow, halting, lame walk with which he passed the table and reached his seat. His figure was stiffly drawn up and seemed incapable of bending, as though he were suffering from a paralytic contraction of the limbs. . . . Not a muscle of his face relaxed with animation or expression as he stiffly extended his hand..." to the two Republican members of the committee, and after saluting the three Democratic members, he "took off his elegant, silk-lined overcoat, stiffly turned round and seated himself at the table, while settling at the same time a large handkerchief in his breast pocket."

His sober, highly rational testimony, lasting over two and one-half hours, emphasized emphatically that he had no knowledge, information or suspicion of cipher correspondence until it appeared in the Tribune: "I had no cipher; I could not read a cipher; I could not translate into a cipher." When saying this, he hit the table with his clenched fist. When he referred to the bribes alluded to in the cipher dispatches, his faint hoarse voice became loud, vehement, and dramatic: his face flushed and "the mental excitement had such mastery over him that his lips twitched, and one of his hands, said to be smitten with paralysis, trembled in a most painful manner."[320] He had not selected or sent the Democratic "Visiting Statesmen" to the South. Firmly he asserted, "No offer, no negotiation, in behalf of any member of the Returning Board of South Carolina, of the Board of State Canvassers of Florida, or of any other State was ever entertained by me, or by my authority or with my sanction. No negotiation with them, no dealing with them, no dealing with any one of them was ever authorized or sanctioned by me in any manner whatsoever."[320]

With righteous anger and frustration, he declared, "to the people who, as I believe, elected me President of the United States; to the four million and a quarter of citizens who gave me their suffrages, I owed duty, service, and every honorable sacrifice, but not a surrender of one jot or tittle of my sense of right or of personal self-respect" exclaimed an embittered Tilden. "I was resolved that if there was to be an auction of the Chief Magistracy of my country, I would not be among the bidders."[321] Goaded by Republican congressman Frank Hiscock's bitter and intensive questioning, Tilden finally exploded: "I declare before God and my country that it is my entire belief that the votes and certificates of Florida and Louisiana were bought, and that the Presidency was controlled by their purchase." And replying to Hiscock's request for proof, Tilden argued that the committee's investigation had sufficient evidence for this declaration. After a few more hostile questions from Hiscock and G. B. Reed, Republican of Maine, Tilden was excused: he had had his final day in court.

Tilden's testimony closely reflected a popular Democratic view: that the electoral votes of Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina were for sale, that a few of Tilden's closest friends knew this and at a minimum were not averse to negotiating a purchase, but they did not buy them. Rather, Republicans secured the votes. In addition, Republican managers got access to the telegraphic dispatches of both parties, destroyed their own, and publicized those of the Democrats. From the time the Hayes administration took over in March 1877, Returning Board members and all other Republicans associated with the election returns in the disputed states had been rewarded with offices. And finally, according to this Democratic perspective, the Republicans, with "virtuous indignation," held up the dispatches to prove that Tilden was a "fellow who wanted to steal but was not smart enough."[322]

Tilden's testimony, together with Edward Holden's report on the cipher dispatches, completed the investigative phase of the Potter Committee's inquiry on the alleged electoral frauds in the 1876 presidential election. Over 200 witnesses had been examined, over 3,000 pages of testimony published. The committee's majority report on 3 March 1879 reflected the views of the seven Democrats: (1) the Canvassing Board of Florida reversed and annulled the choice of its residents; (2) the choice of the people of Louisiana was annulled and reversed by the Returning Board; and (3) Samuel J. Tilden, not Rutherford B. Hayes, was the real choice of a majority of the electors duly appointed by the several states and of the voters.[323]

The minority report argued that no evidence was presented as to the dishonesty of the canvassing boards in Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Rather, the Tribune publication of the cipher dispatches showed that the very men who had been loudest in their denunciations of the boards had tried to corrupt the electoral process in those states with money. According to the evidence, the minority report specified that no Republican dispatches were intentionally destroyed, and that the innocence of Democratic leaders such as Colonel Pelton and Samuel Tilden was not established.[324] These reports concluded the painful series of electoral investigations begun over two years earlier: the two major political parties remained bitterly divided. The next presidential nominating conventions were fifteen months ahead. Although Tilden believed he could be nominated and elected in 1880, he wrote on 18 June to the New York delegates at the National Democratic Convention in Cincinnati: "In renouncing my renomination ... it is a renunciation of reelection. ... To those who think my . . . reelection indispensable to an effective vindication of the right of the people to elect their own rulers.. I have accorded all along a reserve of my decision as possible, but I cannot overcome my repugnance to enter a new engagement which involves four years of ceaseless toil . . . such a work is now, I fear, beyond my strength."[325]

Was Tilden correct in writing of "reelection" to the office of the president? Had he actually won the popular balloting in 1876 only to lose the electoral vote? He deeply believed this. And much historical evidence supports this interpretation. Had there been a fair election in South Carolina and Louisiana in which Black voters were protected, Hayes would have won those states. In Florida, under similar conditions, Tilden would have triumphed.[326]

The cipher telegram congressional investigations and the newspaper publicity generated by Whitelaw Reid in the New York Daily Tribune had clearly exhausted the leading Democratic candidate. Indeed, a proud Reid, soon after the story broke in 1878, predicted the cipher revelations "have made an effective end of any political future he may have had."[327] The election strains left Tilden with a shattered body, a slow shuffling gait, and increased "numb palsy" or paralysis agitans: in sum, an old broken man at the age of 66.[328] And perhaps the final irony to the story of the cipher telegrams and the election of 1876 is to be found in the successful Republican candidate in the election of 1880. The presidential victor, Ohio congressman James A. Garfield, had been a member of the 1877 electoral commission!

[272] New York Daily Tribune, 10 September 1878.

[273] Ibid., 5 September 1878.

[274] The editor of the New York Herald on 10 October 1878 printed a more balanced interpretation regarding secret communications: "The fact that they were in cipher affords no reasonable presumption against the honor and integrity of either receivers or senders. Politicians on both sides had an interest in concealing their movements from their adversaries. The resort to a cipher was no offence against political morality so long as the objects attempted to be accomplished were legitimate."

[275] Bingham Duncan, Whitelaw Reid: Journalist, Politician, Diplomat (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1975), 68.

[276] C. Vann Woodward, Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and The End of Reconstruction (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1951), 19.

[277] Charles A. Beard & Mary R. Beard, The Rise of American Civilization (New York: MacMillan Co., 1942), 2:3 14.

[278] Paul Leland Haworth, The Hayes-Tilden Disputed Presidential Election of 1876 (Cleveland: The Burrows Brothers Company, 1906), 333. Historian Bernard A. Weisberger made the wise observation that the compromise was "engineered by the businessmen of both parties, quintessential conservatives, who did not want the already struggling economy hit with political paralysis or renewed warfare." Cf. Bernard A. Weisberger, American Heritage 41 (July-August 1990): 19.

[279] As quoted in Hodding Carter, The Angry Scar: The Story of Reconstruction (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1959). 342.

[280] U.S., Congress, House Select Committee on Alleged Frauds in the Late Presidential Election, Cipher Telegrams, 45th Congress, 3d session, 1879, H. Rept. 140, part 2, 1 (hereafter cited as Cipher Telegrams, H. Rept 140).

[281] Ibid., 22.

[282] U.S., Congress, Senate Sub-Committee of the Committee on Privileges and Elections, Testimony on the Electoral Vote of Certain States, 44th Congress, 2d session, 1877, Misc. Doe. 44 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1877), 1 (hereafter cited as Testimony, Misc. Doe. 44).

[283] Ibid., 425–26.

[284] John R.S. Hassard, "Cryptography in Politics," North American Review 128 (March 1879), 319.

[285] Alexander Clarence Flick, Samuel Jones Tilden: A Study in Political Sagacity (Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press, 1963), 429–30.

[286] Testimony, Misc. Doe. 44,440.

[287] New York Times, 8 February 1877. The Times identified the Detroit newspaper as the Tribune.

[288] Ibid., 439. This particular edition is not located in the Library of Congress nor in the British Museum catalog that lists a similar volume, though published in London and New York, 1872. However, the Library of Congress does have The Household English Dictionary, published in Edinburgh and New York, for 1876 but not 1872. This edition may have been the book used by Patrick, Miller and Pelton for their masked dispatches since it provides the key for decoding the messages.

[289] Ibid., 442. A special Detroit dispatch to the New York Times, 8 February 1877, incorrectly described the dictionary as having three columns on each page and also mistakenly said that the sender turned back two pages to choose the corresponding word, counting from the top of the page. The New York Daily Tribune, 7 October 1878, made the same error of specifying four pages instead of eight columns. The four-page description is repeated in Hassard, "Cryptography," North American Review 128:322.

[290] Testimony, Misc. Doe. No.44, 449–451.

[291] Ibid., 448.

[292] Ibid., 448.

[293] Ibid., 449.

[294] Ibid., 456.

[295] Ibid., 442–58.

[296] Ibid., 407. In testifying, Corse doubted he sent the telegram; however, if he did, he stated, it was "mere badinage." Cf. Testimony, Misc. Doc. 44,407.

[297] Ibid., 409.

[298] Ibid., 409.

[299] Ibid., 410.

[300] Ibid., 411.

[301] Ibid., 412.

[302] Ibid., 490–91.

[303] Ibid., 504–05-

[304] New York Daily Tribune, 22 June 1880.

[305] Cipher Telegrams, H. Rept. 140, 2. Also cf. U.S. Congress, House Select Committee on Alleged Frauds, 45th Congress, 3d session, Misc. Doe. 31 Part IV (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1879) 4:110 (hereafter cited as House Misc. Doe. 31).

[306] New York Daily Tribune, 4 September 1878.

[307] Duncan, Whitelaw Reid, 248.

[308] Hassard, "Cryptography," North American Review, 128:315–25.

[309] Allen Johnson and Dumas Malone, eds., Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1931), 6:382–383.

[310] Ibid., 6:26.

[311] House Misc. Doc.31, 4:111.

[312] Whitelaw Reid in testimony before the House Committee in January 1879 stated "I think that the key to the Oregon dispatches was first discovered by somebody in the West, and that it had been published in some Western paper." Ibid., 4:111.

[313] Ibid., 7 October 1878.

[314] Dumas Malone, ed., Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Charles Seribner's Sons, 1932), 5:136–37.

[315] House Misc. Doe. 31,4:112.

[316] Testimony on the Electoral Vote of Certain States contains lengthy testimony from William Pelton, George L. Miller, John M. Corse, and three dozen others involved in the Oregon case during hearings between December 1876 and March 1877: cf, Testimony, Misc. Doc. 44. Much more extensive testimony, provided in January and February 1879, involving manipulations in Oregon and the Southern states is to be found in the House Select Committee on Alleged Frauds documents: cf. House Misc. Doc. 31, Part 4.

[317] The Holden report on his reconstruction of the codes and ciphers may be found in the House Misc. Doc. 31,4:325–33 1.

[318] William F. Friedman and Lambros D. Callimabos, Military Cryptanalytics (Washington, D.C.: National Security Agency, 1956), 1:97–99.

[319] New York Herald, 9 February 1879.

[320] House Misc. Doc. 3 1,4:273.

[321] Ibid., 4:274.

[322] New York Herald, 10 February 1879. John Bigelow, editor, author, and diplomat, and Tilden's close friend and biographer, was much more harsh in his indictment: ". . . during the whole four years of Hayes' administration, and regardless of Mr. Tilden's age, his physical infirmities, his priceless public service, and the place which he occupied in the hearts of his countrymen, he was pursued by the agents of that administration with a cruelty, a vindictiveness, an insensibility to all the promptings of Christian charity, which men are rarely accustomed to exhibit except in their dealing with wild beasts." John Bigelow, The Life of Samuel J. Tilden (New York: Harper & Brother, 1895), 2:169.

[323] House Report 140,67.

[324] Ibid., 69–77.

[325] Flick, Tilden, 456.

[326] Flick, Tilden, 415. H. J. Eckenrode, Rutherford B. Hayes: Statesman of Reunion (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1930), concludes that if Florida votes had been honestly tabulated, Tilden won the presidency, and the electoral votes should have been Tilden 188 to Hayes 181: 193. Vann Woodward in Reunion and Reaction, 20, agrees that recent historical scholarship holds that Hayes was probably entitled to the electoral votes of Louisiana and South Carolina; however, Tilden should have been given Florida's four electoral votes, thus giving him 188 votes and the presidency. Pulitzer-prize-winning Allan Nevins, also Leon B. Richardson and William Dunning, awards Florida to Tilden. A notable dissenter, Paul Maworth, in his Hayes-Tilden book, argues that in a free election, the three Southern states, Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, would have returned substantial majorities for Hayes and therefore the election of Hayes was the proper one, 330–32,341.

[327] As quoted in Duncan, Whitelaw Reid, 71.

[328] Flick, Tilden, gives a good medical analysis of Tilden's health, 417.