In January 1898, four years after his retirement from the State Department, John Haswell wrote a very realistic and discerning letter on communications security to the elderly secretary of state, John Sherman. Explaining that the present code of the State Department had been in use for almost twenty-five years, he warned the former Ohio senator, "It is well known that the European telegraphic system is an adjunct to the Postal arrangement of each country." Sensitive to European espionage practices, Haswell continued, "Every telegraphic cipher message entering into or passing through a country is sent to the Foreign Office and referred to the Bureau of Ciphers, where it is recorded and efforts are made to translate it. This is the rule adopted by the powers for all government communications."

Alert to the codebreaking activities of foreign governments, Haswell continued in his letter to caution the secretary, as John Bigelow had sought to convince William Seward earlier, that the interception of foreign dispatches was commonplace. Haswell explained, "In France the Cipher Bureau, attached to the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, employs from fifteen to twenty clerks whose sole duty is to classify all such messages with a view to obtain as complete a knowledge of the codes of the various countries as possible. It cannot be questioned that however complete a code may be, in the course of twenty-five years the trained efforts of these Bureaus would have given them at least a very good general knowledge of the cipher of the Department."[392]

In late 1897 and early 1898, threats and rumors of war with Spain over the issue of Cuban independence continued to shape the headlines and crowd the front pages of American daily newspapers, especially the "Yellow Press" along the eastern seaboard. Undoubtedly, war fever and the danger of foreign intervention influenced Haswell as he sought greater security for American dispatches. He wrote that since European Black Chambers operated freely, and probably possessed copies of the State Department's 1876 Cipher, "it would seem good policy, after a service of twenty-five years to establish a new and improved system of telegraphic communication between the Department and its Diplomatic Agents."[393]

Eager to prepare a new code, Haswell also argued that all cablegrams should be sent in code, no matter how unimportant: it is crucial that secrecy be maintained. Furthermore, the State Department code should be completely changed so that cryptographic information in the hands of foreign governments would not apply to the new code. For economy, the sentences in the old code would be changed and many new ones introduced, thus making it different from the old one, and also reducing the expenses of cable transmission. And, finally, he suggested no specific stipend for himself for the preparing the codebook, leaving that decision to the department.

On 24 March 1898, during the same hectic week that the war with Spain was declared, Haswell finally received an answer to his proposal. Because of his experience, the needs of the department (weeks earlier, General Horace Porter, the American minister to France, had alerted the State Department that the Spanish government probably had the department's 1876 code) and also his earlier codebook, Haswell received the desired assignment from Sherman. The secretary had earlier endorsed the idea for better communications security in a January letter. And Sherman needlessly warned the cautious Haswell: "Nor will it be necessary to call your attention to the confidential character of the undertaking. The Department therefore confidently believes that you will exercise the greatest care in order to prevent a knowledge of its preparation, or any of the material from getting into the possession of unauthorized parties, whereby its usefulness might be impaired. Your compensation will be $3,000."[394]

Within a year, Haswell's codebook was submitted to the department and accepted by Sherman's successor, the experienced secretary of state, John Hay. Instructions for its use emphasized that the volume, each one numbered, was to be considered as special property entrusted to heads of missions and these officers were to deliver copies to their permanent or ad interim successors in office and require a special receipt in duplicate for the book.

Anxious about developing better security measures, John Hay added that if a head of mission left his post on leave or otherwise, he had to return the book under seal by safe and speedy conveyance to the State Department or place the volume in the temporary custody of some diplomatic or consular officer of the United States. Here again, duplicate receipts must be filed. If no officer was available, then the volume in a sealed envelope was to be delivered to a United States naval officer with the request that he deliver it safely and promptly to the department. The codebook must never be placed in the possession of the archives custodian. And, finally, only the head of mission or the first secretary of the embassy or legation could have access to The Cipher of the Department of State.[395]

The extensive codebook, which became known as the Blue Code, remained the State Department's primary codebook for the next eleven years. Its title page is identical to the 1876 codebook except that John Haswell is listed as the author. This similarity between the two codebooks probably resulted in the former book coming to be identified by the color of its cover, red, and the latter, blue. Less than ten months after completing this second generation State Department codebook, John Haswell died on 14 November 1899.[396]

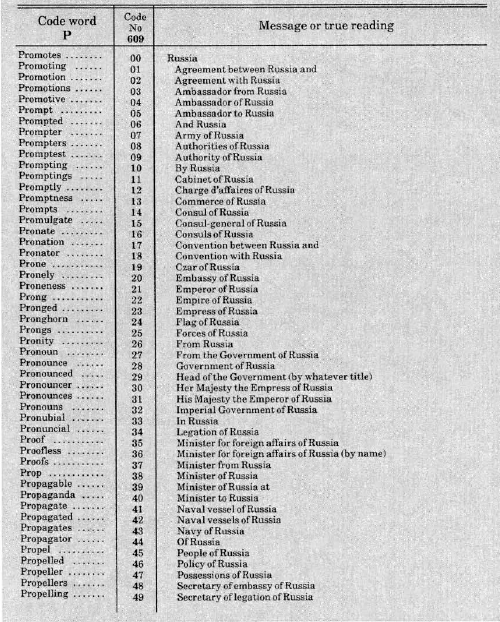

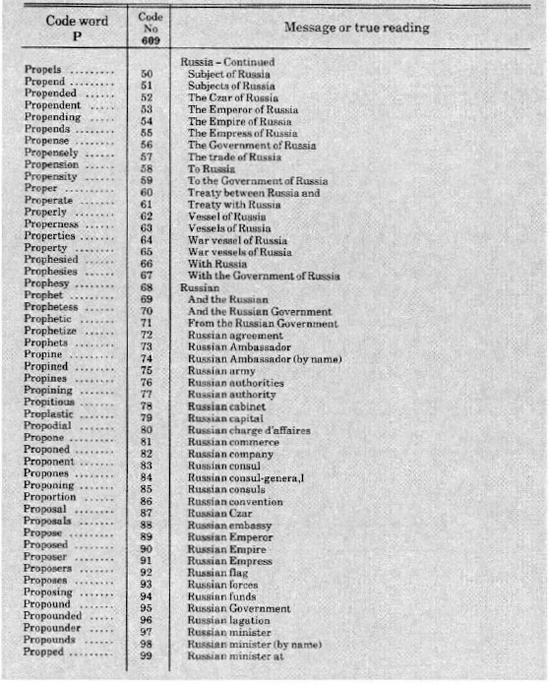

The 1899 edition resembles the earlier codebook in design and format. Whereas the first book left blank spaces for adding additional plaintext words and/or phrases at the end of each alphabetical code group, the later one left the spaces at the beginning of each code group. Thus, the word A was masked by the code number "10000" and the code word "Aaron" in the first tome; in the second book, the respective codes were "10425" and "Accessibly." Also the second book expanded the plaintext words and phrases beginning with A to 8,650 items, thus 2,582 more than the 1876 book. The 1899 book numbered almost 1,500 pages compared to 1,200 in Haswell's first volume. For both books, and especially the latter, Haswell selected plaintext words and phrases that were common in American diplomatic correspondence.

Haswell explains in the instructions section that the International Telegraphic Conference held in Paris determined that ten letters or four figures constituted one word. Each codeword in this book consisted of ten or fewer letters. However, code numbers contained five figures, and therefore each group of figures constituted two words and would be assessed double charges. Though lacking in economy, the code numbers had the advantage over the word system because of its applicability to all languages that contain numerals.

Therefore, Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Russian, and Turkish operators who often committed critical errors in transmitting word messages were familiar with figures, and thus transmitted them with accuracy. However, more recently, these telegraphers became more skilled, and especially those personnel in charge of international transmissions achieved a much higher level of accuracy in transmitting and receiving foreign language messages. Because of this and the additional fact that fewer errors were being made during transmission of the large volume of commercial messages that use code words, Haswell wrote that "it seems advisable that the economical advantages offered by the Code Word system be availed of, and its use in preference to the use of the figure system is therefore recommended."[397] Unreasonable concerns about economy again drove the State Department communications security system.

Sometime later, probably several years, a revised instruction was added to the codebook. Because of telegraph tariff revisions, the new guideline specified there was now no added expense in transmitting five-digit code numbers. Thus, the department recommended that code numbers be used because figures are similar in almost all languages, and fewer mistakes result when code number groups are transmitted.

A Spelling Code, to be used for proper names and certain places, in the 1899 codebook also resembled the first edition. The following example indicates how the fairly complicated procedure had to be followed. If the code clerk wished to encode the phrase "John Hay, our former Ambassador to Great Britain, is now Secretary of State," the plan required the clerk first encipher the name, John Hay. He had to find the number corresponding to the first code word in the dispatch. Thus, the first plaintext word after the name was our, and the codeword for it was "MUSLINET" and code number, "52940." This codenumber had to be written and partially repeated over the name John Hay.

5 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

J | O | H | N | H | A | Y |

Then the clerk had to substitute for the plaintext letters with the distorted alphabets specified by the numbers. Table No. 1 at the back of the book was used for the first five letters. Thus, for plaintext J, the fifth distorted alphabet provided the letter T. In distorted alphabet No.2, S was found for plaintext O. Alphabet No. 9 gave an A for an H: alphabet No. 4 showed "I" for N: alphabet No. 0 listed "N" for H. The clerk then was required to turn to Table No. 2 to complete the masking of the last two plaintext letters that followed the same design as Table 1 : distorted alphabet No. 5 showed a "B" for plaintext A, and alphabet No. 2 listed "F" for Y. (See chart below.)

For decoding the spelling code letters, the process was reversed: the numbers of the Key Group should be placed under the spelling cipher letters, and the numbers indicated the particular distorted alphabet from which these letters were selected. The letters in the regularly arranged alphabet over the cipher letters provided the plaintext letters.

Also prepared by Haswell to accompany the 1899 codebook was the sixteen-page Holocryptic Code, An Appendix to the Cipher of the Department of State, also published by the Government Printing Office in 1899. The thin hardcover book resembled the holocryptic codebook devised by him a quarter of century earlier. The new edition, devised for "greater security," had seventy-five rules, twenty-five more than the earlier one. These rules described additional secret systems for veiling the messages: 1) thirty-four rules for changing the message route into two, three, and four columns; 2) thirteen rules for adding specific numbers to the codenumbers; 3) twelve rules for subtracting numbers from the code numbers; and 4) a series of thirteen miscellaneous rules such as substituting the first code word or code number for the second, the second for the first, the third for the fourth, and fourth for the third, etc. Haswell's 1876 edition did not include subtraction rules.

All the rules were designated by short familiar words, primarily the names of animals such as "cow" and "bison" and "dog." All these names could be found in the codebook's plain text, and thus the sender, when employing a particular rule for encrypting the message, revealed to the recipient that rule had been used by prefixing to the message the code number or code word of the plaintext rule. This code number or code word was termed the "indicator."

The instructions also specified that indicators could be interpolated into any part of the encrypted message: all the encrypted message after the indicator had to be translated by the recipient in accord with the rule specified by the indicator. Under the general remarks, Haswell again emphasized that the location of the indicator code word or code number should never change; it invariably had to be the first item. With genuine enthusiasm, Haswell concluded his instructions in the Holocryptic Code book with the following statement: "It is believed by the compiler of these Rules that their application to the Code Vocabulary will secure the utmost secrecy and render cipher messages wholly inscrutable."[398] And for the harried code clerks, he added, "Facility in the use of these Rules will come with practice and will render the extra time needed for their application quite inappreciable in comparison with the object accomplished."

How did John Haswell evaluate his new codebook in describing it to the American public; what were its principal characteristics and merits? Here is his unique appraisal, published in a popular monthly magazine twelve years after his death (he did not note in the article that he designed the book): "The cipher of the Department of State is the most modern of all in the service of the Government. It embraces the valuable features of its predecessors and the merits of the latest inventions." Sensitive to the cipher's considerable size, Haswell explained, "Being used for every species of diplomatic correspondence, it is necessarily copious and unrestricted in its capabilities, but at the same time it is economic in its terms of expression."

Gratified that the design offered State Department code clerks a readily convenient mask, Haswell wrote proudly, "It is simple and speedy in its operation, but so ingenious as to secure absolute secrecy." He concluded his appraisal with a somewhat mysterious sentence that must have been calculated, for security reasons, to veil the nature of the secret system. He wrote of the "key" to the cipher and did not explain that one could simply unlock the State Department cipher by obtaining the codebook. Instead he wrote, "The construction of this cipher, like many ingenious devices whose operations appear simple to the eye but are difficult to explain in writing, would actually require the key to be furnished for the purpose of an intelligible description of it."

A significant addendum to the Blue Codebook was made in September 1900 by Alvey A. Adee, acting secretary of state, who was then in his thirty-first year of service to the State Department (this Shakespearean scholar and perceptive administrator served almost fifty-five years, leaving the department only a week before his death in 1924 at the age of eighty-one).[400] This annex described the precise method for encoding the time and date that the telegram was sent: its purpose -economy: "giving the information at the smallest possible expense."[401] Numbers and letters shaped the code:

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

O | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | J | K | L | M |

The letters were used for hiding the month and the hour of the day: the twelve numbers signified the month and hour. The month was to be named first, and was represented by a letter in alphabetical order: January, being the first month, was represented by "A, " February, "B"; the code continued on to December, which was "M." The letter "I" was not part of the code since it often was confused with "J."

Each day in the month was represented with two letters: "OA" represented the first day of the month; "OK" for the tenth day; and "AC" for the thirteenth day. An important rule stated that the letter "O" was placed in front of any letter representing any one of the first twelve numbers so that the date was always represented by two letters, preventing a possible mistake if one of the letters was dropped during transmission. This mistake would change the date from the end of the month to the beginning. Finally, the month-day-hour group, which was always five letters in length, gave the hour of the day or night represented by a letter that was followed by the letter "A" for A. M., or "F" for P. M,: "N" for midnight; "M" for noon.

A dispatch filed at 7 P.M. on 3 September would begin with "JOCGP," since September is the ninth month; "OC" for the third day; and "GP" for the seventh hour of the afternoon. Another example: a telegram sent at noon on 28 February would begin with "BBHMM" for the second month, 28th day, and twelve noon.

Again, these instructions emphasized economy by stating that cable and telegraph companies agreed that a five-letter group was one word.

Secretary of State John Hay sent the very first copy of the codebook and holocryptic code by way of Paris to Bellamy Storer, the new envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to Spain in May 1899. "In the diplomatic pouch, securely sealed in a wooden box" and addressed to General Horace Porter, the American minister in Paris, the secret book and appendix were to be given to Storer when he called at the embassy on the way to Madrid.[402] Storer, a fifty-one-year-old lawyer and former Ohio Republican congressman, had just completed two quiet years as minister to Belgium, an appointment that came as a reward for his support of William McKinley in the 1896 presidential election.

Storer, faced with negotiations in Spain on such difficult postwar problems as the status of church property in the Philippine Islands, the return of Spanish prisoners of war held in those islands, and also the release of Cuban political leaders in Spain, might well have needed the innovative codebook. Hay told him about the new code and instructed him to deposit it in the archives of the legation in Madrid after signing the original receipt, which had to be returned to the State Department. Aware of European espionage skills because of his prior service as secretary of the American legation in Paris under John Bigelow, Hay added, "The greatest care should be taken by you to insure the safety and preserve the secrecy of the cipher."[403]

Despite all the State Department warnings about exercising special security precautions, the new codebook was stolen in St. Petersburg sometime before mid-1905 and the appointment of the new American minister, George von Lengerke Meyer, to that post.[404] Although President Theodore Roosevelt angrily denounced the lack of proper security procedures that resulted in loss of the codebook, the State Department failed to publish a new codebook. Rather, this 1899 volume and appendix would remain the primary State Department encryption system until 1910 when the Green Cipher: The Cipher of the Department of State appeared.[405] And despite the book's loss a decade earlier, President Woodrow Wilson and his trusted advisor, Colonel Edward House, would use the 1899 book for their private correspondence in the early years of World War I.

[392] John Haswell to John Sherman, Washington, D.C., 26 January 1898. Copy in author's possession. In the printed directions for the new codebook, Haswell did not mention intercept practices as a reason for the new book; rather, he simply noted "Changed conditions in general and reasons of a special character have made it desirable for the Department to have a new and enlarged Code": cf. The Cipher of the Department of State (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1899), 5.

[393] Ibid.

[394] John Sherman to John Haswell, Washington, D.C., 24 March 1898. Copy in author's possession.

[395] John Hay instructions sent with letter of Alvey Adee to John Haswell, Washington, D.C., 20 March 1899. Copy in author's possession.

[396] The Times Union (Albany, N.Y.), 15 November 1899.

[397] The Cipher of the Department of State (1899), 7.

[398] Haswell, Holocryptic Code, 16.

[399] John H. Haswell, "Secret Writing: The Ciphers of the Ancients, and Some of Those in Modern Use," The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, 85 (November 1912), 92.

[400] A dedicated worker, Adee slept on a cot in his office so that he could be available to decode the latest messages from Madrid and Havana during the growing crisis with Spain in the spring of 1898: cf. John A. De Novo, "The Enigmatic Alvey A. Adee and American Foreign Relations, 1870–1924," Prologue (Summer 1975), 77.

[401] This page appearing above Adee's name and dated 14 September 1900, is bound into the Blue Code book just before the title page.

[402] Hay to Porter, Washington, D.C., 19 May 1899. Diplomatic Instructions of the Department of State, 1801–1906, Microcopy 77, Roll 64, National Archives.

[403] Hay to Storer, Washington, D.C., 19 May 1899, Instructions, Microcopy 77, Roll 150. National Archives.

[404] George von Lengerke Meyer to Theodore Roosevelt, St. Petersburg, 5 July 1905, in The Presidential Papers of Theodore Roosevelt, Series 1, Roll 56: also Roosevelt to Meyer, Oyster Bay, 18 July 1905, in Elting E. Morison, ed., The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1951), 4:127.

[405] Ralph E. Weber, United States Diplomatic Codes and Ciphers, 1775–1938, 246.