2

Standardizing or Constructing a Measurement Scale

2.1. Introduction

Measurement scales are essential tools for measuring latent variables such as attitudes, opinions, preferences and behavioral intentions. Since these constructs are not directly observable, it is necessary to acquire the means to reproduce, through a set of directly observable indicators (variables), these implicit phenomena. Indeed, it is widely recognized that these phenomena are omnipresent and decisive in understanding facts, not only from an academic point of view, but also from a managerial point of view. From this perspective, the use of scales (often multi-item) has been made very apparent in recent years. Some researchers tend to use existing measurement scales, while others design their own.

In this chapter, we will address the central question: is scale construction always useful? Indeed, it is easy to observe the existence of already developed measures that are conceptually defined as representative of the same phenomenon. Moreover, it is clear that sometimes the use of identical measures often does not produce the expected results. It is then legitimate to ask yourself a set of questions:

- – is it appropriate to operationalize the same phenomenon via different scales?

- – is a scale always capable of grasping the phenomenon studied in different situations?

- – is it still necessary to use a new scale?

In short, should we reuse or build a scale? We will discuss the criteria for making this decision.

2.2. Existing or new scale: a range of choices

The phenomena studied in marketing are often the subject of multiple questions, such as the study of materialism, fidelity, satisfaction, their antecedents and consequences on consumer behavior in several situations (cultures, products, etc.). The facts raised are not considered as definitive. This implies the frequent use of the same theoretical constructs in order to extend the reflections and discussions around these phenomena of common interest. This leads researchers to replicate not only these constructs and some of the relationships associated with them, but also sometimes the measures that have been used in their past examinations. Is such standardization of scales still possible and useful?

In addition, a review of the literature on measurement scales shows that the number of scales developed has been increasing since the conception of Churchill’s famous paradigm (1979), normalizing the construction of scales. Some, on the other hand, have been used exclusively for a single research project or a limited number of research studies, thus limiting the value judgments that can be made about them. This raises the question of whether the proliferation of scales is always beneficial.

In fact, each of the possibilities offered is subject to discussion, intertwining both merits and limitations, and a real dilemma remains. It can be added that beyond this alternative (adopt or develop), it is common to observe other possibilities based on scale adaptations. In this section, we will clarify the potential for standardization and the construction of new scales on the one hand, and the different possibilities for action (adoption, construction and adaptation) on the other.

2.2.1. Standardizing or constructing a scale: benefits and limits

Here we will trace the main benefits and limitations that can be drawn through the use of existing scales compared to the creation of new scales, the objective being to highlight the potential of this alternative in a research process.

2.2.1.1. The arguments in favor of adopting (standardizing) existing measurement scales

A reliable and valid scale must be able to extract meaning not only on the measurement of the phenomenon (concept) it claims to operationalize, but also on the relationships that may exist with other phenomena (concepts), demonstrating its predictive or nomological1 validity. This can only be demonstrated by the multiplicity of applications of the measure. Bruner (1998) pointed out that several uses of a scale, on different populations and situations, are required in order to achieve the psychometric objectives of validating the measure in question. For his part, Peter (1981) has long pointed out that a single study is not enough to establish the validity of a construct. Indeed, the process of validating a scale, which we will develop further on, is a continuous and iterative process. Standardizing the measurements makes it possible, it is true, to ensure a certain degree of replication of the scales, to undertake the comparison between the results of several studies and, finally, to extract valid generalizations. The acquisition of knowledge related to the phenomena studied is greatly aided when a comparison between research results is possible. Using the same measures is indeed likely to promote such investigations.

In this regard, Hinkin (1995) attests that the use of standardized measures makes it easier not only to compare results, but also to facilitate the development and testing of theories. This is all the more interesting because a large majority of research, particularly in marketing, is based on data from convenience samples2. The possibility of using the same instruments, when possible, allows us to get closer to the true value of the observed phenomena.

In addition to the undeniable benefits of using the same scales (which are now accessible through the web), it is obvious that standardization saves time and costs which would have been necessary to support the development of new reliable and valid scales. This leads to a facilitation of research processes and a faster accumulation of knowledge around the phenomena studied.

2.2.1.2. Arguments in favor of developing new measurement scales

Certainly, use of the same measures has undeniable benefits. However, this is not always possible because it is not always useful. Indeed, it is not uncommon to observe that an existing scale cannot be retained for use in different contexts. For example, to measure attitudes towards supermarkets, Yu et al. (2003) found that the semantic differential scale they used was not equivalent in two different cultures (United States and Hong Kong). Cultural differences may change the meaning of some aspects of the phenomena studied or even the emergence of some specificities that are not operationalized in existing measures. This limit can be extended to other situations, such as the specificities of the populations studied (other than cultural), the products handled, etc., hindering or making it difficult to use existing scales that carry erroneous meanings about the phenomena studied. Kalafatis et al. (2005) added that the use of an existing scale is not without problems. According to them, a scale may not be stable over time and may endorse different results when replicated. Indeed, it is likely that individuals’ grasping (over time and across groups) of the measurement of the phenomenon itself and its understanding will be different. Frisou and Yildiz (2011) suggest that, in this regard, as the constructs themselves are not always stable over time, the use of a scale requires the ability to ensure that the constructs and their measurements are concordant. Similarly, Baumgartner and Steenkamp (2006) point out that constructs can contain two components: the first, stable; the second, temporal and therefore dynamic.

These findings implicitly suggest that the measurement of a construct does not necessarily always lead to an observation approaching the true value of the phenomenon. The development of new scales allows for a better consideration of the specificities of the situation in which the phenomenon subject to operationalization is studied. It is, therefore, risky to conduct research on the basis of scales already created when their ability to correctly grasp the constructs analyzed has not been established.

2.2.2. A continuum of possible choices

It is curious to note that the researcher is not exclusively faced with a dual choice: reusing an existing scale or developing a new one. These are only the two extreme ends on a continuum of possible choices. In this section, we will first discuss the main modes of use and then the precautions to be taken during use.

2.2.2.1. A scale’s modes of use

In the process of operationalizing a construct, it is possible to make a multitude of decisions related to items (number, formulation, etc.), dimensions of the latent construct in question, response formats (number of points, etc.), etc. These variants are not always used in the same way. All these choices imply consequences (see Chapters 5 and 6) on the whole process of operationalizing the constructs, of which we must be perfectly aware. It can then be said that between standardizing and constructing, it is possible to decide adapting, which is a question of introducing modifications to an already developed scale. It is probably interesting to note, in this respect, that the changes undertaken may be more or less important.

Often, many young researchers talk about constructing or adapting a scale in order to operationalize their concepts, when it is only a simple operation of translating a scale that does not fundamentally affect the measurement of a construct. This translation simply involves the adoption of an existing scale. Translating means making the tool comprehensible to a respondent using a language different from the one with which the scale was initially formulated, in the same way as an interviewer can do when administering a questionnaire face-to-face, making it comprehensible without any fundamental changes (same number of items, same response format, etc.). Of course, it is possible to translate while adapting at several levels (deleting and/or adding items, modifying the response format, etc.) or even build a scale while using some items, especially translated items, from other scales.

Strictly speaking, when is it a question of scale construction, adaptation or just scale standardization (translation)?

Farh et al. (2006) start from two dimensions, namely: first, the source of the scale (use of an existing scale or construction of a new scale) and second, the cultural specificities of the context of its application (identical or different) and propose four configurations for using a measurement scale of a construct: 1) translation: when a scale exists and there is an absence of cultural differences, 2) adaptation: when a scale exists but cultural differences also exist, 3) decontextualization: construction of a scale if none exists and when the construct is supposed to be invariant across cultures, 4) contextualization: construction of a scale if none exists and cultural differences exist. These four modes of use, according to Farh et al. (2006), are summarized in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1. Scale usage configurations proposed by Farh et al. (2006)

Scale source Cultural specificities |

Existing scale | Construction of a new scale |

| Identical | Translation | Decontextualization |

| Different | Adaptation | Contextualization |

He and Van De Vijver (2012) support three options: 1) adoption: use of an existing or even translated instrument, 2) adaptation: use of an existing scale to which some modifications are made and 3) assembly: construction of a new scale.

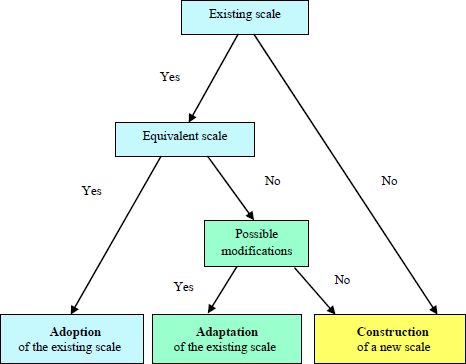

In order to make the generally available choices easier to read, we have summarized in Figure 2.1 the different options based on the main rules governing the decision.

Figure 2.1. Modes of use of a measurement scale

2.2.2.2. Precautions for use

It is probably relevant to note that some researchers mistakenly believe that they have adapted, or even constructed, a scale simply by selecting a set of indicators, or even dimensions, from other scales and grouping them together to measure a phenomenon. In the absence of a clear definition of the phenomenon and justifications on the usefulness of such a way of proceeding, it is impossible to support this collage of items from other scales. Indeed, without verifications both conceptual (definition of the construct and its components) and empirical (experts to attest the validity of content, statistical tests to determine the dimensionality and validity of the construct, etc.), assuming that such an undertaking is correct does not make sense.

It should be noted that this meticulous examination is not only important during the process of constructing a scale, but also during the adaptation or even adoption of a scale. It is also crucial, in any research process using scales (adopted, adapted or constructed), to specify all their characteristics (item formulation, number of items, response labels, number of points, dimensionality, reliability, validity, etc.). This undertaking not only attests to the consistency of the approach but also allows for more rigorous comparisons between research results and an assessment of the relevance and potential for use of the selected scales. In the absence of sufficient information and justification relating to the measurement scales, some results lose their scientific grounding.

2.3. Reflection points to facilitate the choice of a scale’s mode of use

From the previous sections it seems that the construction of a scale is not always necessary. It is even legitimate to think that you must have very good reasons to develop one. The adoption of scales allows for faster, less painful and less costly knowledge development. Admittedly, for several reasons, this is not always possible. This decision must not, therefore, be taken hastily. In this section, we will first examine the basis for such a decision. As a second step, we will propose a reflection on the equivalence of a measurement scale to several situations.

2.3.1. The basis for the decision

The criteria and steps associated with the decision of a type of scale use from among all the possibilities offered (adopt, adapt, develop) are numerous. To help you make a better-informed decision, we will present two main points: first, the logic behind the decision; second, the central criterion to retain for this.

2.3.1.1. The logic of the decision

In order to choose a mode of use, it is necessary to start by looking for existing scales related to the field of the construct studied. If this is the case, it is necessary to consider whether scales can be adopted in the context of a specific research project. Bruner (2003) took a close interest in this issue and proposed a five-step process to resolve the issue. These steps can be summarized as follows:

- – define the latent construct to be measured;

- – determine if a multi-item scale is the most appropriate measurement mode;

- – investigate if measurement scales of the studied construct are already developed;

- – if several scales exist, they must be compared on the basis of a set of criteria: face validity, psychometric qualities, previous uses of the measurement, description of the scale (source, origin, reliability, changes made, etc.);

- – if no scale is available or if existing ones are not appropriate, a measure based on a widely accepted scale development procedure must be constructed.

This sequence of steps, which seems to be appropriate for reflective3 measurement models, can be extended to formative4 measurement models while taking into account their specificities (see Chapter 3, section 3.2), particularly on the type of evaluation criteria (cases where, for example, it is not possible to retain a Cronbach alpha-type reliability measure for formative models). However, the use of an existing measurement scale often requires much more than just translating the scale. The adaptation of a few words, a few items, the response format and/or any other aspect may be considered necessary. It is very important to justify the applicability of the scale not only through its past and present psychometric qualities, but also through, on the one hand its adequacy for the theoretical context of the study (definition of the construct, its facets, its boundaries in relation to other concepts) and, on the other hand, for its specific application context (culture, product, type of store, target population, etc.). Some constructs (and therefore their measures) are only relevant in some research contexts and not in others.

Moreover, why should we seek to verify the nature of conceptual relationships in a new context? Simply, because there is reason to believe that the phenomenon may be different and that it is necessary to take the time to check whether realities established in other contexts (especially foreign ones) are still present. If it is possible to assume that conceptual relationships may vary, then it is legitimate to assume that not only can responses to items on a scale vary from one group of respondents to another, but also that the scale with all its components (formulation of items, labels used, label numbering, etc.) can be assessed and interpreted differently.

2.3.1.2. Equivalence, a central criterion in the decision to standardize a scale

Several researchers have attempted to provide answers to this problem by studying the invariance of their scales in different contexts (Mullen 1995; Nyeck et al. 1996; Steenkamp and Baumgartner 1998; Lopez et al. 2008). It appears that in order to standardize, it must first be ensured that the application of the scale gives rise to the same rules for assigning numbers for measuring the phenomenon; in other words, that the resulting scores are comparable. This clearly suggests that there is a need to ensure that the scale is equivalent to the new application being considered.

To illustrate this concept of equivalence, we can mention the measurement of weight (kilogram or pound), distance (kilometer or mile) or temperature (Celsius or Fahrenheit). Can the scores obtained on one measurement scale be considered equivalent to the other or should they be converted? That said, equivalent measures should lead to similar conclusions. The basis for choosing an option (adopt or develop) is thus whether an existing scale is capable of giving scores that can be comparable and not subject to equivalence bias when replicated. More explicitly, equivalence is ensured when the study of variations of a phenomenon over time and groups of individuals reflects real variations of the phenomenon under consideration and not variations that are due to the specificities of the measurement of the phenomenon.

2.3.2. The search for equivalence

The adoption of a scale requires a long process of reflection on its potential to represent the phenomenon under study in the required situation. In fact, all the particularities of a scale are concerned. In this section, we will first try to shed light on which elements the ambivalence of the choice between standardizing and constructing a scale can relate. As a second step, we will point out the advantage of undertaking a series of examinations to certify the equivalence of a scale.

2.3.2.1. A wide range of attributes

As we have pointed out, the search for equivalence involves several aspects. Without attempting to make an inventory of all the attributes that can be covered by this review, we will present some of them. Case et al. (2013) mentioned, among other things, the equivalence of the construct: in this case, it is a question of examining whether a construct gives rise to the same meaning in different cultures (or groups). According to the authors, this equivalence may concern different aspects itself, in particular whether the items represent the construct in the same way and are subject to the same interpretation according to the groups of individuals questioned. Yeh et al. (2014) pointed out that one of the most important factors in considering equivalence is culture. Yeh et al. (2014), Farh et al. (2006) and many others discussed two fundamental notions associated with a construct. It is the emic construct specific to the culture and the etic construct that is universal or invariant across cultures. Caramelli and Van De Vijver (2013) stressed that when conducting intercultural studies, it is imperative, before using a scale, to carefully examine its ability to represent the same phenomenon across different cultural groups. Although the question of the invariance of a scale has been the subject of much debate, it is curious to see from He et al. (2008) that, in intercultural marketing studies, researchers often overlook this aspect. While standardizing scales is, as we have already pointed out, likely to promote the validation of measurements and the comparability of research results, it is still necessary to check beforehand whether the scales in question converge or are invariant in their meanings from one group to another in order to be able to generalize their adoption.

Standardization, in which some researchers seek refuge for ease of use, may well hinder the quality of the conclusions found if it is not appropriate. For example, Case et al. (2013) focused in particular on examining the errors that can be endorsed when translation problems affect the measure. They observed that the lack of true equivalence leads respondents to misunderstand the items, leading to a multitude of inconsistencies, including: greater reliance on central responses (average or neutral), away from the respondents’ actual opinions, a different scale structure (of the dimensions and/or items making up the components), etc. Such errors hinder the research process insofar as the use of the scale cannot bring us closer to the realities to be studied.

Moreover, Bartikowski et al. (2005) pointed out that even translation equivalence can cover several aspects. Lopez et al. (2008) noted that translation equivalence implies that items can be translated in a way that does not change the meaning of the item. This task is not often easy, especially since some languages have richer syntaxes than others. Indeed, translation is sometimes not enough to capture the meaning that individuals in a group give to an item. It should be noted that the translation effort to seek equivalence must also affect the response modalities, which sometimes leads to an increased difficulty. Indeed, in some cultures involving different languages, some positive words have no negative counterparts (Rozin et al. 2010), limiting the use of certain scale formats, such as semantic differential.

In addition, aspects relating to the design of a scale (scale format, response labels, etc.) are often considered as ancillary elements compared to its content (items, dimensions); however, numerous studies prove the opposite. The design attributes of a scale can have many consequences on the evaluation of a phenomenon. Although the design of a scale is discussed further in subsequent chapters (particularly Chapter 5), it should be noted for information that Weijters et al. (2010), having tested the effects of different Likert scale formats (depending on the number of response echelons, the wording of all response options, or only the ends, or the presence or absence of a neutral point), observed that respondents’ evaluations of the same items may differ. Weijters et al. (2010) therefore point out that data from different formats are not necessarily comparable. This is why it is important to choose the right format and justify it. These justifications increase confidence not only in the measures used but also in the results that emerge from their operations.

Before concluding this debate, it is probably useful to note that the standardization of a scale, in order to undertake comparisons between different groups of individuals (especially in intercultural studies), requires extending concerns about equivalence to many other aspects such as the sample (characteristic, size) and the administration of the instrument (mode of administration, timing of administration, etc.), as they can have an impact on the quality of the scale and the results obtained.

Without dwelling further on the various possible concerns for equivalence, it should be noted that He and Van De Vijver (2012) have tried to establish a synthesis of the three main types of bias that can produce invalid, and therefore non-equivalent, scores following the use of a scale, namely:

- – construct biases, when the construct is not identical across groups (cultures) or when the behaviors associated with the construct are not well represented;

- – method biases, due to perverse factors arising from sampling (sample characteristics, etc.), instrument characteristics (measurement format, etc.) or administration processes (administration mode, ambiguous instructions, etc.);

- – item biases, which can be caused by poor translation, ambiguous words, etc.

It is clearly established that researchers must, therefore, undertake significant intellectual work to authorize the use of the said scale among the population concerned. This, of course, should not be limited to the past psychometric qualities of the scale or to the efforts often made in translating items, but equivalence does concern the overall content of the scale (definition, dimensions and items) and its design (measurement format, response labels, adopted numbering, etc.).

2.3.2.2. A thorough examination

Kalafatis et al. (2005) pointed out that a properly developed scale does not mean that one can borrow or use it without further development and testing. This reflection is legitimate since, for example, to circumvent certain response biases such as the tendency for respondents to agree5, scale designers may use reversed items or other strategies to avoid it (see Chapter 5), but when adopting such a mixed scale (with regular and reversed items), it must be ensured that this tactic does not lead to further bias across the groups studied, ultimately damaging the measure. As such, some researchers have established different interpretations of mixed items that may indeed have as their origins the individual and cultural differences of respondents leading, when exploited, to problems of equivalence (Weems et al. 2003; Wong et al. 2003).

Far from the translation and back-translation concerns that scale users often encounter, it is appropriate to use committees of experts (other than linguists) and interviews with individuals in the population concerned to ensure the proposals’ response and the content of the items. Indeed, the translation (of items and/or response modalities) may be linguistically good, but nevertheless not reflect a behavior, a feeling, etc., in short, content that the item is supposed to capture. A quick translation without hindsight and a thorough examination of the meanings of terms, their connotations, their applications, etc., in the context of the study incurs a high risk of measurement errors.

Coupled with all the efforts to translate a set of indicators listing the phenomenon to be measured, adaptations may also be necessary for the new situation, such as adding items (to cover other specific aspects of the construct in the context of the study), avoiding certain formulations (in particular reversed-negative formulations when the risk of confusion is high), changing the response format (Likert or semantic differential, number of response echelons), etc. But a careful translation, or even an adaptation of the scale, does not always give the same scale structure with acceptable psychometric properties when applied in a new context, and checks are required. Not testing the dimensionality, reliability and validity of an existing scale in a new context (especially linguistic) means accepting the risk of obtaining a measure that may deviate from the phenomenon to be measured. Comparisons between groups using a scale of measurement assessed differently (meaning, structure, items comprising the different dimensions, etc.) are therefore not acceptable.

The examination of equivalence can involve several methodological and data analysis processes and protocols. Depending on the type of equivalence studied, the researcher may use, for example, expert interviews to verify the significance of the construct, exploratory data collections in order to examine, regarding the targets of the respondents, the understanding of the items, exploratory factor analyses6 to verify the dimensionality7 of the construct in the different groups and items by factor, etc. A detailed examination of the scale is essential to ensure equivalence at several levels. Seeking to demonstrate the equivalence of one aspect to the detriment of others may obscure the overall understanding of the phenomenon to be measured.

2.4. Conclusion

The construction of a scale is not an end in and of itself. If reliable and valid scales are available, allowing the operationalization of the studied constructs, it is preferable to use them. This allows for an easier research process, a better comparison of the results of different research projects and therefore, a better validation of what has been learned, which is likely to lead to the advancement of knowledge. Obviously, this possibility can only be considered once the equivalence of said scale has been tested in the context of the study undertaken and therefore only after a careful examination of its qualities (translation, meaning, dimensions, reliability, etc.) has been established. Indeed, establishing the equivalence of a scale allows the comparability of the resulting scores following its application in different groups and contexts. In addition, it should be remembered that even if some scales are available from past studies, the researcher may have to adapt them because they may not correspond perfectly to the construct to be measured, the context of the study, etc. In the absence of an equivalent scale or even the possibility of its adaptation, it is then appropriate to construct one. Deciding to adopt, adapt or develop a scale requires a lot of thought to choose the option that will give adequate measures to use.

2.5. Knowledge tests

- 1) What are the advantages of adopting a measurement scale?

- 2) What are the advantages of developing a new measurement scale?

- 3) How does one decide on the adoption or construction of a measurement scale?

- 4) When is it necessary to adapt a measurement scale?

- 5) A simple translation operation on an existing measurement scale gives rise to which form of use: adoption, adaptation or construction?

- 6) On which aspects a scale can be adapted?

- 7) How can one judge the equivalence of a scale for future use?

- 8) On what criteria can the study of the equivalence of a scale be based?

- 1 Predictive validity seeks to establish a relationship between the (studied) phenomenon and only one of its antecedents or consequences, according to a theoretical framework. Nomological validity seeks to establish relationships between the (studied) phenomenon and others, according to a theoretical framework. For more details, see Chapter 7.

- 2 A convenience sample is an empirical (nonprobability) sample. The selection of individuals from the population concerned may be based on their availability, willingness to participate in the study, etc.

- 3 A reflective measurement model is a measurement scale of a latent construct whose observable indicators (items) represent the manifestations (consequences) of the construct. The construct is reflected by its indicators.

- 4 A formative measurement model is a measurement scale of a latent construct whose observable indicators (items) represent the sources (causes) of the construct. The construct is formed by its indicators.

- 5 The tendency of a respondent to “agree” (acquiesce) expresses his or her tendency to agree with the proposed item, regardless of its wording, by opting for answers such as “strongly agree” or “agree”.

- 6 Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is a multivariate analysis that, while based on the study of interdependence relationships between a set of variables, allows the structure of a phenomenon to be explored and thus, a simplified structure of the initial retained variables (items) synthesized into a few factors (dimensions) to be extracted. See Chapter 6 for more information on EFA.

- 7 The dimensionality of a phenomenon explains its underlying factors (its structure). A construct can be uni-dimensional: formed of a single latent variable, the construct purchase intention is often considered as uni-dimensional. A construct can be bi-dimensional: formed of two latent variables; for example, the construct regret is often seen as having two underlying dimensions: regret for action and regret for inaction. A construct can be multidimensional: formed of several latent variables (3 and more); for example, the construct materialism is often seen as multidimensional. See Chapter 6 for more details on dimensionality study.