How Codes Are Used for Reimbursement

The Price Is Right

When you go to the grocery store and purchase a can of beans, you are pretty certain that you are being charged the same price as everyone else, the price that is posted on the shelf. If you pick a different brand the price may be higher or lower, but once again the price will be the same for everyone. But—wait a minute—if you have a supermarket discount card for the clerk to scan, your price after the discount could be less.

Healthcare prices work the same way. If you are a self-pay patient with no insurance, you will be billed the full price and will be expected to pay it. If you have medical insurance, your insurance company will be billed the same price but will pay less, due to contractual agreements with the providers. If you are able to qualify for a public assistance health insurance program due to your income level, the bill will still be the same, but that program will also pay less than the full amount.

Here’s what the reimbursement for your surgeon’s bill for your appendectomy might look like:

Procedure: |

Appendectomy |

CPT code billed: |

44950 Appendectomy |

Surgeon’s charge: |

$1,250 |

If you are a self-pay patient with no insurance, you will be expected to pay the $1,250.

If you have Medicare, the payment amounts will look like this:

Insurance: |

Medicare |

Surgeon’s charge: |

$1,250 |

Medicare fee schedule amount: |

$638 |

Medicare payment: |

80% × $638 = $510 |

Patient coinsurance: |

20% × $638 = $128 |

What happens to the other $612 ($1,250 – $638) that nobody is paying for? This amount is known as the “contractual allowance.” In exchange for being a Medicare provider and receiving payments from Medicare, the physician has in essence entered into a “contract” to accept what Medicare pays. The contractual allowance is the difference between the physician’s charge and the amount he or she has agreed to accept. Even if you have secondary insurance that covers what Medicare does not pay, it will only pay your 20% co-insurance; it will not pay the contractual allowance.

If you have a commercial insurance carrier, the payment might look like this:

Surgeon’s charge: |

$1,250 |

Insurance: |

Commercial Express |

Fee schedule amount: |

$700 |

Insurance payment: |

80% × $700 = $560 |

Patient coinsurance: |

20% × $700 = $140 |

Contractual allowance: |

$550 |

If your insurance is a health maintenance organization (HMO) or preferred provider organization (PPO), you may have a limit on the amount you have to pay out of pocket—usually a flat rate. In that case, the payment could be:

Surgeon’s charge: |

$1,250 |

Insurance: |

HMO Hometown |

Fee schedule amount: |

$600 |

Patient copay for surgery: |

$100 |

Insurance payment: |

$500 |

Contractual allowance: |

$650 |

Hospitals also have charges, which are often two to four times what they expect to collect from insurers and managed care plans. One of the reasons for this is that hospitals routinely quantify the amount of bad debt and charity care they provide. This helps with fund-raising and is used to meet charitable obligations. However, valuing these at full charge greatly overestimates the amount of bad debt and charity care actually provided. Those who pay full charge are usually patients with HSAs, foreign patients, and the uninsured. This is known as cost shifting. In most hospitals, only 3% of total revenue comes from patients who are uninsured, primarily because they are unable to pay. Almost half of all personal bankruptcies are related to medical bills (Anderson, 2004). Hospitals and other providers can, and do, turn accounts over to collection agencies, garnish wages, and file property liens in order to collect.

Hospitals have come under increasing criticism of their practices with regard to uninsured patients. In February 2004, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) clarified its position on charges. Previously, the industry interpretation of government regulations about charges was that all patients had to be billed using the same schedule of charges. The new interpretation offers more flexibility to hospitals that want to offer discounts to certain patients. HHS clarified that hospitals may develop their own indigency programs with their own definitions, but maintained the stipulation that the criteria must be applied uniformly to Medicare and non-Medicare patients. The result of these changes is that uninsured patients may get the same types of discounts that large payers receive via the contractual allowance.

Geographic location also makes a difference in the amount of reimbursement to both physicians and facility providers. Although Medicare is thought of as a national program, the methods used to calculate reimbursement take into account what is known as a Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI, pronounced “gypsy”). Office space is cheaper in Mississippi than in Boston, and the cost of malpractice insurance also varies from state to state. Each CPT code has a relative value (RVU) associated with it, composed of values for physician work, practice expense, and malpractice insurance cost. The total RVU is multiplied by a dollar amount conversion factor and the GPCI to get the fee schedule amount for a specific area. The Medicare fee schedule has to be budget neutral, meaning that the total expenditure on health care cannot change. This means that if the value of one procedure code goes up, one or more of the others must go down.

Staking a Claim

Regardless of the type of insurance, almost all reimbursement to healthcare providers and facilities is based on procedure and diagnosis codes. Payers receive this information on a claim form, usually submitted electronically. More than 99% of Medicare Part A claims and 95% of Medicare Part B claims transactions are submitted electronically.

There are two types of claim formats used by different types of providers. The CMS-1500 claim format is used by physicians and mid-level providers who are billing independently, whereas the CMS-1450 or UB-04 claim format is used by hospitals, home health agencies, ambulance services, rehab facilities, dialysis clinics, and other facilities. It is important to understand that although CMS continues to refer to the CMS-1500 and the CMS-1450 in its regulatory documentation, the industry now refers to the claim submission formats as “5010” or “837.” The 5010 format was agreed upon by the Accredited Standards Committee (ASC) of the American National Standards Institute in an effort to standardize claims submission across all payers. Implementation of the 5010 format, as of January 1, 2012, was also important because it accommodated the increased number of characters required by ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS codes (CMS, 2013a).

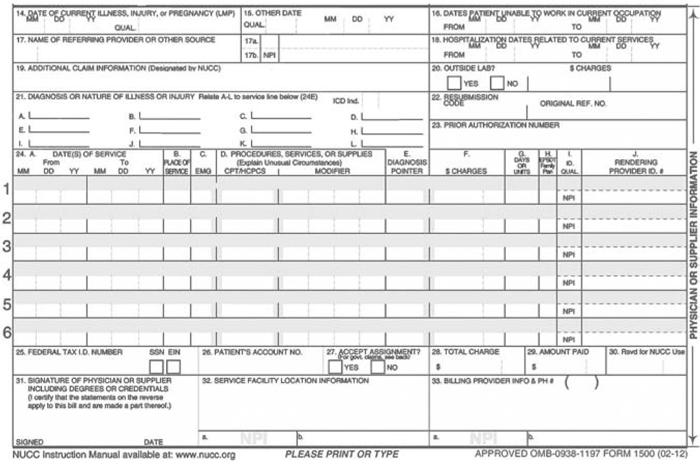

CMS-1500 Form or 837P (Professional) Format

The electronic format has space for 12 diagnosis codes and 6 procedure codes (Figure 4-1). A unique feature of the CMS-1500 is the ability to link a procedure code to one or more of the diagnosis codes. This is important in providing medically necessary justification for procedures performed. An example of this situation would be a patient brought to the emergency department after a traffic accident. The patient has a closed fracture of the radius, a bone in the arm. The physician treats the fracture with closed reduction and casting. However, the patient is also experiencing chest pain, and an electrocardiogram is performed to assess the condition of the patient’s heart. The diagnosis codes listed on the claim form are for closed fracture, radius, and a second code for chest pain. Under normal circumstances, a third-party payer would not think that an EKG was medically necessary for an arm fracture. However, if the diagnosis of chest pain has been linked to the EKG procedure code, that will tell the payer the real reason for the EKG, and the payer would then most likely pay the claim.

FIGURE 4-1 CMS-1500 Form or 837P (Professional) Format.

Courtesy of NUCC.

The line on which each procedure (CPT or HCPCS code) is reported also has columns for the date(s) of service, place of service, type of service, up to four modifiers, the diagnosis code link, the charge for the service, and the number of days or times (units) the procedure was performed.

The 1500 form also has spaces for the provider’s identification and tax ID number, patient demographic and insurance information, referring physician information required for consultations and diagnostic testing, and other information related to processing the claim and determining whether it will be paid.

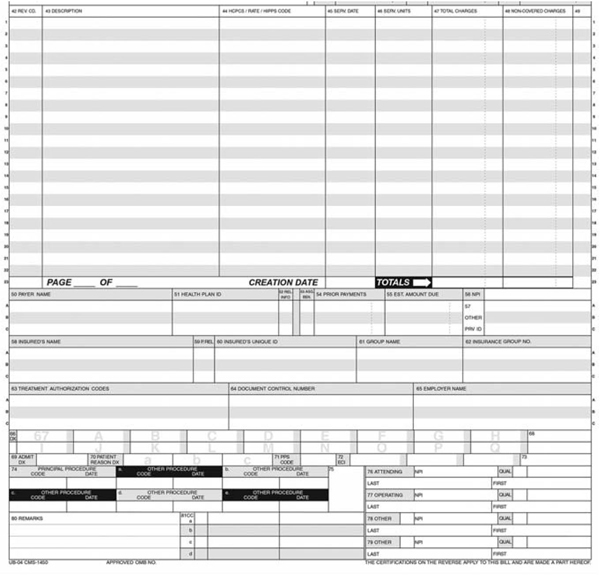

CMS-1450 or UB-04 Form or 837I (Institutional) Format

The UB-04 form (Figure 4-2) has space for more diagnosis codes than the CMS-1500 form (principal diagnosis, plus 24 others, as compared to 12 on the CMS-1500). However, it is not possible to link the procedures to a specific diagnosis. There is also room for the principal procedure and 24 others, with a date space adjacent to each procedure code.

In addition to the reported diagnosis and procedure codes, the UB-04 uses revenue codes to lump together the charges for different categories of services, such as radiology, IV solutions, and drugs. The claim form contains the revenue codes with the number of service units for each and the total charge. The only time that individual procedure charges are itemized on a UB-04 is for hospital outpatient procedures paid under prospective payment (see “Payment Methodologies” later in this chapter).

FIGURE 4-2 CMS-1450 or UB-04 Form or 837I (Institutional) Format.

Courtesy of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Claims Submission

Claims are sent from the provider or facility to the payer via one of three methods:

![]() Paper. Although the days of a clerk printing out a paper claim form are almost gone, there are still providers who submit claims manually, on paper forms. CMS requires all payers except facilities with fewer than 25 full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) and other providers with fewer than 10 FTEs to file initial claims electronically (CMS, 2013b).

Paper. Although the days of a clerk printing out a paper claim form are almost gone, there are still providers who submit claims manually, on paper forms. CMS requires all payers except facilities with fewer than 25 full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) and other providers with fewer than 10 FTEs to file initial claims electronically (CMS, 2013b).

![]() Electronic via billing entity or clearinghouse. These businesses submit claims on behalf of providers. They may format billing data to meet the needs of individual payers and perform edits on the billing data to verify completion of all required fields.

Electronic via billing entity or clearinghouse. These businesses submit claims on behalf of providers. They may format billing data to meet the needs of individual payers and perform edits on the billing data to verify completion of all required fields.

![]() Electronic direct. Electronic submission of claims has the advantage of speeding up the payment process. It requires less processing by the payer than manual paper claims and usually employs front-end edits to ensure correct, or “clean,” claims.

Electronic direct. Electronic submission of claims has the advantage of speeding up the payment process. It requires less processing by the payer than manual paper claims and usually employs front-end edits to ensure correct, or “clean,” claims.

Claims Processing and Adjudication

Once the insurance company or other payer has received the claim information, either electronically or on paper, it processes the claim. This can involve extracting data from the claim, scanning claims for retention, and validating specific data elements. Checking the claim at this point may result in rejection of the claim for reasons having nothing to do with the diagnosis and procedure codes, such as the following:

![]() The payer cannot identify the patient as being insured with his or her company.

The payer cannot identify the patient as being insured with his or her company.

![]() The patient’s coverage with the payer terminated before the date of service on the claim.

The patient’s coverage with the payer terminated before the date of service on the claim.

![]() The time limit for filing the claim has expired.

The time limit for filing the claim has expired.

![]() It is a duplicate claim.

It is a duplicate claim.

The claims adjudication process involves review of the claim to make sure that the service provided is covered under the specific insurance plan and that all required information is available. Adjudication of physician or other professional services claims occurs at the line-item level, charge by charge by charge. One line of a claim may be paid, but others rejected. In addition to deciding whether a specific charge will be paid, the adjudication process also determines how much will be paid. The payment amount is based on the fee schedule amount for that procedure, the place of service, and any applicable contract stipulations. Another factor will be whether you, the patient, have met your deductible for the current year. If not, you will be liable for the portion of the reimbursed amount that is less than or equal to your deductible. You will be paying the doctor instead of the insurance company paying the doctor.

Many, many errors on the part of the payer are possible during the claims adjudication process:

![]() Newly enrolled individuals have not yet been loaded into the company’s system.

Newly enrolled individuals have not yet been loaded into the company’s system.

![]() Errors are present in names, dates of birth, addresses, and other demographic information.

Errors are present in names, dates of birth, addresses, and other demographic information.

![]() The payer has incorrectly rekeyed claims information into its own system.

The payer has incorrectly rekeyed claims information into its own system.

![]() The system has programming errors.

The system has programming errors.

![]() The system does not recognize modifiers justifying additional payment.

The system does not recognize modifiers justifying additional payment.

![]() The system has not been updated to reflect new diagnosis and procedure codes.

The system has not been updated to reflect new diagnosis and procedure codes.

![]() Prior authorizations for services have not been loaded into the system.

Prior authorizations for services have not been loaded into the system.

![]() Payment amounts specified in current contracts have not been updated.

Payment amounts specified in current contracts have not been updated.

Claims that require additional information or that need correction of errors are “pended.” The provider is notified of the reason why the claim is pended and what needs to be done. Claims that complete the adjudication process are referred to as “finalized claims.” Finalized claims can be one of three things: paid, rejected, or denied. A payment advice or remittance advice notice is sent to the provider notifying them of the outcome. A check or electronic deposit payment is also sent for paid claims.

Figuring out why a claim has been rejected is often difficult and frustrating. Prior to 2003, approximately 4,000 different remittance advice codes were in use. Many had the same meanings, with minor differences in wording. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 contained an Administrative Simplification provision that addressed the need not only for standardized code sets for diagnoses and procedures but also for standard transactions such as remittance advice codes. As a result, the thousands of remittance advice codes were condensed into a little more than 200.

If you receive an explanation of benefits indicating that a service was denied, it is important to work with your doctor to determine why. In some cases, the insurer may be requesting additional information from you. This could happen in the case of an auto accident, where the auto insurance is supposed to pay first. Another situation like this would be if you were to fall on private property and injure yourself. The property owner’s liability insurance might be the primary payer. You and your doctor are both interested in making sure he is paid, so it is essential that you cooperate in efforts to resolve denials and rejections.

Medical Necessity

Determination of medical necessity involves comparing the procedure being billed to the diagnosis submitted. If you receive a denial notice from the payer that the procedure was “not medically necessary,” it means that your payer does not think the procedure or test was justified for the diagnosis given. Medicare carriers publish what are known as “Local Coverage Determinations” (LCDs) that contain lists of diagnosis codes that validate procedures such as EKGs, chest X-rays, and others. If your diagnosis is not on the list, your claim will be rejected. Screening exams, such as Pap smears, mammograms, and colonoscopies, also are subject to frequency limitations dictating how often they will be paid.

If the provider of the service knows in advance that a service is likely to be deemed not medically necessary, he or she can ask the patient to sign an Advance Beneficiary Notice (ABN) in which the patient acknowledges the possibility the claim will not be paid and agrees to be financially liable for the charge. ABNs must be specific to the service provided; they cannot be blanket forms covering any and all services. Without an ABN signed before the service occurs, the provider cannot bill the beneficiary if the claim is rejected.

Some services are never covered, such as cosmetic surgery. Patients can be billed for noncovered procedures without an ABN.

Instead of rejecting the claim, some payers will “downcode” it based on the diagnosis. For example, if your doctor bills a Level 4 established office visit code (99214) when he sees you for your sore throat, your insurance company may decide that a sore throat should never be more complicated than a Level 3 service. In fact, the insurer may implement a process of rejecting all Level 4 and 5 claims and require physicians to submit additional documentation in order to be paid. This practice penalizes not only physicians who might use the higher level codes without clinical justification, but all other physicians who actually document according to the requirements of the higher levels. The AMA (2005) has developed policies strongly opposing downcoding.

Payment Methodologies

Just as the coding systems are different, the payment methodologies for inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, and professional claims also differ. Many commercial payers follow the lead of Medicare once it has implemented a specific payment system.

FEE FOR SERVICE

The most traditional payment mechanism is known as fee for service. It is simple. A service is billed using a CPT or ICD procedure code. The payer has a fee schedule with a set reimbursement amount for each service it covers. The provider gets the fee schedule amount less any deductible or coinsurance owed by the patient.

Most physician services are paid according to a fee schedule. Clinical laboratory services are paid based on a laboratory fee schedule, and ambulance services on an ambulance fee schedule.

REASONABLE COST OR COST BASED

Under this method, providers or facilities submit an annual cost report that details the expenses of running their businesses. The rules for completing the cost report are extensive. They include data on bed utilization, salaries by cost center, expenses by cost center, indirect costs related to items such as medical education, cost-to-charge ratios (how much it costs to provide a service per dollar charged), capital expenditures, and other items. In many cases the facility has been receiving periodic interim payments from the payer throughout the year, and the cost report is then used to “settle” or reconcile the costs to the payments already received. For Medicare, the cost reports are submitted to the Fiscal Intermediary (FI), which reviews and/or audits the cost report and then submits it to the CMS for reporting.

Periodic interim payments (PIP) are available to inpatient hospitals, skilled nursing facility services, hospice services, and critical access hospitals (small hospitals in rural areas that are needed to ensure access to health care for local populations). Facilities are supposed to self-monitor their PIP payments to ensure they are not receiving overpayments, and penalties are in place if overpayment exceeds 2% of the total in two consecutive fiscal reporting periods.

PROSPECTIVE PAYMENT: INPATIENT HOSPITAL

Government health planners who were interested in restraining the costs of Medicare, Medicaid, and other insurance programs realized that cost-based reimbursement was a sure way to eat up dollars faster and faster. In order to change hospital behavior to encourage more efficient management of medical care, Medicare introduced hospital inpatient prospective payment in 1983. Using a system developed by Yale University in the 1970s, reimbursement to hospitals was based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). Data already appearing on the claim form are used to assign each patient discharge into a DRG:

![]() Principal diagnosis

Principal diagnosis

![]() Complications and comorbidities (CCs)

Complications and comorbidities (CCs)

![]() Surgical procedures

Surgical procedures

![]() Age

Age

![]() Gender

Gender

![]() Discharge disposition (died, transferred, went home)

Discharge disposition (died, transferred, went home)

The principal diagnosis, the reason the patient was admitted to the hospital, determines to which Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) the case will be assigned. There are 25 MDCs, based on body organ system or disease (CMS, 2014):

MDC 1 |

Diseases and disorders of the nervous system |

MDC 2 |

Diseases and disorders of the eye |

MDC 3 |

Diseases and disorders of the ear, nose, mouth, and throat |

MDC 4 |

Diseases and disorders of the respiratory system |

MDC 5 |

Diseases and disorders of the circulatory system |

MDC 6 |

Diseases and disorders of the digestive system |

MDC 7 |

Diseases and disorders of the hepatobiliary system and pancreas |

MDC 8 |

Diseases and disorders of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue |

MDC 9 |

Diseases and disorders of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and breast |

MDC 10 |

Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases and disorders |

MDC 11 |

Diseases and disorders of the kidney and urinary tract |

MDC 12 |

Diseases and disorders of the male reproductive system |

MDC 13 |

Diseases and disorders of the female reproductive system |

Pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium | |

MDC 15 |

Newborns and other neonates with conditions originating in the perinatal period |

MDC 16 |

Diseases and disorders of blood, blood forming organs, immunologic disorders |

MDC 17 |

Myeloproliferative diseases and disorders, poorly differentiated neoplasms |

MDC 18 |

Infectious and parasitic diseases, systemic or unspecified sites |

MDC 19 |

Mental diseases and disorders |

MDC 20 |

Alcohol/drug use and alcohol-/drug-induced organic mental disorders |

MDC 21 |

Injuries, poisonings, and toxic effects of drugs |

MDC 22 |

Burns |

MDC 23 |

Factors influencing health status and other contacts with health services |

MDC 24 |

Multiple significant trauma |

MDC 25 |

Human immunodeficiency virus infections |

Within each MDC, the next partition is based on whether a significant procedure was performed and whether the patient had complications or comorbidities. Patient age and length of stay in the hospital may also affect DRG assignment. There are over 500 DRGs. Those without significant procedures are known as “medical” DRGs, whereas those with significant procedures are “surgical” DRGs.

Once a DRG has been assigned, the determination of the reimbursement amount can start. Each DRG has a relative weight assigned to it. Patients in a given DRG are assumed to have similar conditions, receive similar services, and use similar amounts of hospital resources. The prospective payment system is based on paying the average cost to treat patients in that DRG. The DRG weights are adjusted annually. As might be expected, the more complex the DRG, the higher the weight.

The DRG for a heart transplant has a weight of more than 25.0, whereas the DRG for an uncomplicated appendectomy is less than 1.0. In order to calculate the reimbursement rate, the weight for the DRG is multiplied by a base payment amount, which has geographical wage and cost of living factors built in. In addition, if the hospital is a teaching facility it will receive additional Indirect Medical Education funds. If it treats a disproportionately high percentage of low-income patients, it will receive extra funding as a result.

Some patients are known as “outliers.” This means that the charges for their care greatly exceed the average amount considered normal for a particular DRG. Complications, additional unplanned surgery, or other reasons can cause an outlier. For fiscal year 2014, the charges for the outlier must exceed the DRG payment amount by $21,748. Assume that a patient was admitted for a cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder) with exploration of the common bile duct. This case would fall under DRG 413, and the reimbursement amount would be around $9,803, depending on the geographic location of the hospital. In order to get extra payment over and above the $9,803, the patient’s charges would have to total at least $31,551. Until the charges reached that point, the hospital would not get one extra dime. If a patient is admitted because of a heart attack and falls out of bed, breaking his leg, the hospital will not get any additional money for the extra days that patient will spend in the hospital, unless he eventually becomes an outlier.

Like many other aspects of healthcare reimbursement, the ability to code completely to reach the correct DRG depends largely on physician documentation. Coders are not allowed to make assumptions about what might have been. The presence of laboratory results in a chart indicating the culture of bacteria or a chest X-ray consistent with pneumonia cannot be used for coding purposes unless the physician documents their existence. Because better documentation under prospective payment systems equals better coding, which results in higher reimbursement, physicians have been “urged” to improve documentation by including additional complications and comorbidities. The following list represents diagnoses that can make a payment difference in surgical cases:

![]() Acute blood loss anemia

Acute blood loss anemia

![]() Ileus (intestinal slowdown)

Ileus (intestinal slowdown)

![]() Phlebitis (IV site)

Phlebitis (IV site)

![]() Postoperative infection

Postoperative infection

![]() Respiratory failure

Respiratory failure

Surgeons have been told that documenting these complications demonstrates how sick their patients are. Documenting these conditions in addition to the principal diagnosis also means more money for the hospital.

PROSPECTIVE PAYMENT: AMBULATORY SURGICAL CENTERS

Ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) have been covered under Medicare since 1982. Their primary function is to perform surgical procedures that can be done safely in an outpatient setting, but require a higher level of service than is normally found in a doctor’s office. ASC procedures are generally called “day surgery.” The patient undergoes surgery, receives recovery nursing services, and then goes home the same day.

Unlike the DRG system, the ASC prospective payments are based only on the procedures, with a specific payment rate based on weights from the hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS). If more than one procedure is performed, the ASC receives full payment for the procedure with the highest rate, while most additional procedures are paid at 50%.

Like the DRG system, the ASC rates are updated annually, and newly approved procedure codes eligible for ASC payment are added to the payment scheme. Items covered under prospective payment to the facility include nursing services, recovery room services, anesthetic agents, and supplies such as dressings, casts, and splints. Drugs and implantable devices may or may not be bundled into the facility payment. Payment to the physician performing the ASC procedure is made separately.

PROSPECTIVE PAYMENT: SKILLED NURSING FACILITIES

Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) care for patients who require the skilled services of licensed nursing staff or skilled rehabilitation, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech/language pathology services. In order to qualify for Medicare coverage of skilled nursing, the patient must have been hospitalized for at least 3 days prior to being admitted to the skilled facility and must be admitted within 30 days after being discharged from the hospital. SNFs were paid under a retrospective cost-based system until July 1998. Since then, a payment scheme based on the acuity or illness of the patient has been used. It measures the intensity of care required and the amount of resources used.

Resource utilization groups (RUGs) are similar to DRGs in concept. Each facility is paid a daily rate based on the needs of individual Medicare patients, with an adjustment for local labor costs. Sixty-six individual levels are found within the eight major RUG-IV categories:

![]() Rehabilitation/Extensive Services (9 levels). Patients in this category need extensive medical services, such as tracheostomy care, ventilator/respirator support, or isolation for active infectious disease plus therapy services.

Rehabilitation/Extensive Services (9 levels). Patients in this category need extensive medical services, such as tracheostomy care, ventilator/respirator support, or isolation for active infectious disease plus therapy services.

![]() Special Rehabilitation (14 levels). Based on the number of minutes per week and types of therapy provided.

Special Rehabilitation (14 levels). Based on the number of minutes per week and types of therapy provided.

![]() Extensive Services (3 levels). Extensive medical services but not therapy.

Extensive Services (3 levels). Extensive medical services but not therapy.

![]() Special Care (divided into 2 categories: high and low) (16 levels). Patients receiving parenteral/IV feedings, feeding tube, dialysis, radiation therapy, or respiratory therapy in specific medical conditions such as pneumonia, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, COPD, or skin ulcers.

Special Care (divided into 2 categories: high and low) (16 levels). Patients receiving parenteral/IV feedings, feeding tube, dialysis, radiation therapy, or respiratory therapy in specific medical conditions such as pneumonia, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, COPD, or skin ulcers.

![]() Clinically Complex (10 levels). Conditions such as pneumonia, hemiplegia, burns, surgical wounds, or treatment such as IV medications, chemotherapy, or transfusions.

Clinically Complex (10 levels). Conditions such as pneumonia, hemiplegia, burns, surgical wounds, or treatment such as IV medications, chemotherapy, or transfusions.

![]() Behavioral Symptoms and Cognitive Impairment (4 levels). Patients with hallucinations or delusions, rejection of care, wandering, or physical or verbal behavioral symptoms toward others.

Behavioral Symptoms and Cognitive Impairment (4 levels). Patients with hallucinations or delusions, rejection of care, wandering, or physical or verbal behavioral symptoms toward others.

![]() Reduced Physical Functioning (10 levels). Patients in this category have needs that are primarily for activities of daily living or general supervision, such as bowel training, prosthesis care training, eating or swallowing training, bed transfer training, or splint/brace assistance.

Reduced Physical Functioning (10 levels). Patients in this category have needs that are primarily for activities of daily living or general supervision, such as bowel training, prosthesis care training, eating or swallowing training, bed transfer training, or splint/brace assistance.

The Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) is used to gather and document information about the patient. In addition to information about the patient’s medical condition, the RAI includes a number of items covering functional and social activities, customary habits or practices at home, and psychosocial well-being. The data from the RAI are used to classify the patient into a RUG group, and payment to the facility is based on the group.

PROSPECTIVE PAYMENT: HOME HEALTH AGENCY

To receive home health services covered by Medicare, a patient must be homebound, have a need for skilled nursing care or services such as physical therapy or speech therapy, be under a plan of care periodically recertified by a physician, and receive care from a Medicare-certified home health agency. Agencies receive a lump sum payment to cover each 60-day episode of home health care, based on the patient’s needs. In 2010, this sum was about $2,200 plus market basket and local wage adjustments. A dataset known as OASIS (Outcome and Assessment Information Set) is completed on each client. A home health resource group (HHRG) is assigned based on OASIS data related to the clinical condition and functional status of the patient and the types of services needed.

If the home health agency is well managed and works efficiently, it can keep any profit it makes from the prospective payments by lowering costs per visit or by reducing the number of services while still maintaining a quality outcome for the patient.

PROSPECTIVE PAYMENT: HOSPITAL OUTPATIENT

In August 2000, Medicare implemented a prospective payment system for hospital outpatient services. Similar to DRGs for inpatients, this system is known as Ambulatory Payment Classification, or APC. Like DRGs, each APC contains clinically similar conditions using the same level of facility resources. There are approximately 800 APCs, including procedure-based, medical, and ancillary groups, such as laboratory or radiology testing. The unit of service for an APC is one calendar day. Unlike DRGs, hospitals may be paid a prospective rate for more than one APC per day, depending on the circumstances of the encounter. Multiple surgical services furnished on the same day are subject to discounting. The full APC amount is paid for the surgical procedure with the highest APC weight, and 50% is paid for any other surgical procedure performed at the same time.

APC payment for a given procedure includes facility charges, drugs, supplies, and time. Some items are paid separately on a “pass-through” basis primarily because they may have been developed too recently to have been taken into consideration during the establishment of the APC rates. There is a provision for APC outliers, which may result in increased reimbursement if the total cost for a service exceeds 1.75 times the APC payment and also exceeds a fixed-dollar threshold calculated each year.

RISK-ADJUSTED PAYMENT: MEDICARE ADVANTAGE PLANS

Medicare Advantage Plans, known as Medicare Part C, must provide all Part A and Part B benefits. Some Medicare Advantage Plans also offer prescription drug coverage. These plans are private plans paid on a capitated basis. Medicare uses beneficiary characteristics, such as age, prior health conditions, and the severity of diagnoses reported on claim forms to determine payment rates. Similar to DRGs, the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) system looks at reported diagnosis codes to determine how sick a patient is. A list is published annually by CMS defining which diagnoses qualify for additional risk-adjusted payment. Provider documentation must support the evaluation and treatment of reported diagnoses.

How Payment Methods Affect Coding

Long ago and far away, coding began as a systematic method of tracking disease incidence. Its entanglement with reimbursement systems has greatly increased its importance within healthcare organizations. For years, the hospital medical record departments where coding occurred were dusty file rooms that existed primarily because of documentation-related regulatory requirements. With the implementation of inpatient prospective payment via DRGs in 1983, coding made a difference in reimbursement for the first time. Coders were elevated out of the dark basements into the financial limelight. Medical record departments were transformed into “health information management departments.”

With the newly focused attention on coding, and the potential dollars to be made from using the “right” codes, came the perils of ethical dilemmas and pressure for coders to contribute to the financial success of their employers.

References

American Medical Association. (2005). Model managed care contract. (4th ed.). Chicago, IL: American Medical Association.

Anderson, G. (2004, June 24). A review of hospital billing and collection practices. Testimony before the Committee on Energy and Commerce, United States House of Representatives. Retrieved December 11, 2013, from http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-108hhrg95446/html/CHRG-108hhrg95446.htm

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2013a). An introductory overview of the HIPAA 5010. Retrieved January 20, 2014, from http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/se0904.pdf

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2013b). Medicare claims processing. Publication 100-04. Chapter 24, Section 90. Retrieved January 20, 2014, from http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c24.pdf

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2014). Acute inpatient prospective payment system. Retrieved January 20, 2014, from http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY-2014-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY-2014-IPPS-Final-Rule-CMS-1599-F-Tables.html?DLPage=1&DLSort=0&DLSortDir=ascending