Coding for Dollars

Healthcare Fraud and Abuse

As funding and reimbursement for health care cover less and less of the cost of providing care, the temptation to find “loopholes” in the reimbursement systems grows.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) established a Fraud and Abuse Control Program, effective January 1, 1997. The Office of Inspector General (OIG) carries out nationwide audits, investigations, and inspections in order to protect the integrity of HHS programs. Included as subjects of the investigatory efforts would be any healthcare program that receives and distributes federal funds. The OIG also has the authority to investigate hospitals, pharmaceutical manufacturers, third-party medical billing companies, ambulance companies, physician practices, nursing facilities, home health agencies, clinical laboratories, hospices, and companies that supply durable medical equipment, prosthetics, and orthotics. In other words, almost anybody and everybody associated with health care. The OIG can also involve the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) or other federal agencies, as needed, to assist with investigations.

The HHS OIG is primarily concerned with compliance, which means establishing a business environment that complies with principles of business practice, as identified by the OIG, that are intended to increase the stability of the Medicare Trust Fund by reducing fraud and abuse in the claims process. Fraud can occur due to deliberately unethical behavior or because of mistakes and ignorance of the law.

The OIG has the force of law behind its investigations and prosecutions. Some of the laws it enforces cover business processes and relationships:

![]() The “Stark” laws (named after Congressman Pete Stark of California) address financial interests of physicians in companies or services to which they refer patients or submit claims. An extensive list of designated services is covered.

The “Stark” laws (named after Congressman Pete Stark of California) address financial interests of physicians in companies or services to which they refer patients or submit claims. An extensive list of designated services is covered.

![]() The Anti-Kickback statute prohibits the knowing payment of anything of value to influence referral of federal healthcare program business.

The Anti-Kickback statute prohibits the knowing payment of anything of value to influence referral of federal healthcare program business.

![]() Patient antidumping statutes were passed as a result of the days in which hospitals would do “financial triage,” placing the poor and uninsured back into the ambulance and sending them to the public hospital. These laws require that any patient presenting for emergency care be given an appropriate medical screening exam to determine whether he or she has an emergency condition. If such a condition exists, the patient must be stabilized before being discharged or transferred.

Patient antidumping statutes were passed as a result of the days in which hospitals would do “financial triage,” placing the poor and uninsured back into the ambulance and sending them to the public hospital. These laws require that any patient presenting for emergency care be given an appropriate medical screening exam to determine whether he or she has an emergency condition. If such a condition exists, the patient must be stabilized before being discharged or transferred.

Civil monetary penalties may be imposed on corporations or individuals found to have violated federal regulations related to healthcare financial transactions. The maximum civil monetary penalty is currently $10,000 per item or service, with the possibility of triple penalties in some instances. Some of the actions for which civil monetary penalties may be imposed include the following (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], n.d.):

![]() Submitting a claim or claims that the person knows or should know is for an item or service that is not medically necessary

Submitting a claim or claims that the person knows or should know is for an item or service that is not medically necessary

![]() Failing to provide an itemized statement when requested by a Medicare beneficiary

Failing to provide an itemized statement when requested by a Medicare beneficiary

![]() Making unsolicited telephone contacts with Medicare beneficiaries regarding furnishing covered durable medical equipment

Making unsolicited telephone contacts with Medicare beneficiaries regarding furnishing covered durable medical equipment

![]() Billing for an assistant at a cataract surgery

Billing for an assistant at a cataract surgery

![]() Charging a beneficiary for completing and submitting claim forms

Charging a beneficiary for completing and submitting claim forms

![]() Charging a Medicare beneficiary more than the limiting charge (nonparticipating physicians or suppliers)

Charging a Medicare beneficiary more than the limiting charge (nonparticipating physicians or suppliers)

![]() Hiring an individual who has been excluded from participation in federal healthcare programs

Hiring an individual who has been excluded from participation in federal healthcare programs

Exclusion from federal healthcare programs can occur as a result of convictions for program-related fraud and patient abuse, licensing board actions, and default on health educational assistance loans. The exclusion extends beyond direct patient care or billing and claims to any type of receipt of federal funds, even a salary for serving as an administrative functionary. Employers who knowingly hire excluded individuals may themselves be fined or prosecuted. A list of excluded individuals and entities is available on the HHS OIG website. During fiscal year 2012, the OIG excluded 3,131 individuals and entities from participating in federal healthcare programs. The following were some of the reasons for exclusions:

![]() Licensure revocation (1,463)

Licensure revocation (1,463)

![]() Patient abuse or neglect (212)

Patient abuse or neglect (212)

![]() Criminal convictions for crimes related to Medicare and Medicaid (912)

Criminal convictions for crimes related to Medicare and Medicaid (912)

![]() Criminal convictions for crimes related to other healthcare programs (287)

Criminal convictions for crimes related to other healthcare programs (287)

Consider the following example exclusion cases from 2012, as reported by HHS (2013):

![]() In Texas, a nurse was convicted for capital murder for injecting bleach into dialysis lines, killing five patients. Exclusion for 60 years.

In Texas, a nurse was convicted for capital murder for injecting bleach into dialysis lines, killing five patients. Exclusion for 60 years.

![]() In Ohio, a pediatrician was convicted for unlawful sexual contact with a minor. Exclusion for 50 years.

In Ohio, a pediatrician was convicted for unlawful sexual contact with a minor. Exclusion for 50 years.

![]() In California, a physician was convicted for involuntary manslaughter related to inappropriate administration of Propofol and patient abandonment. Exclusion for 50 years.

In California, a physician was convicted for involuntary manslaughter related to inappropriate administration of Propofol and patient abandonment. Exclusion for 50 years.

One of the ways the OIG gets information on questionable practices is through qui tam, or “whistle-blower,” suits. Qui tam litigation allows private citizens to act on the government’s behalf in filing lawsuits alleging that an individual or corporation has violated the federal False Claims Act. Anyone who has information about the practices of a provider can be a whistle-blower. In some cases, that individual turns out to be a current or former employee of the organization being investigated. The whistle-blower may receive up to 25% of the money the government recovers.

Recent settlements of qui tam fraud cases during the past few years have been quite dramatic. For example, U.S. Renal Care agreed to pay $7.3 million to resolve allegations it billed for more Epogen than it actually administered to patients. Epogen is used to treat anemia often found in end-stage renal disease patients. Manufacturers of Epogen supply about 11% more drug in each vial than is listed on the label, because it is impossible to extract all of the drug from the vial with a syringe. The extra amount is called “overfill.” Between 2004 and 2011, the company billed Medicare for the extra percentage of Epogen, even though it was not administered. This qui tam case was brought by a registered nurse who formerly worked at the company and who had tried to remedy the situation internally, to no avail. She will receive $1.3 million.

Similarly, Imagimed LLC, a New York–based company, will pay $3.57 million to resolve allegations that from 2001 to 2008 it conducted MRI scans with contrast media and without direct supervision by a physician, despite federal regulations requiring such oversight because of the potential for a serious adverse reaction, such as anaphylactic shock. This case was brought by another radiologist, who will receive $565,500.

During fiscal year 2012, the OIG won or negotiated over $3.0 billion in healthcare fraud judgments and settlements. Enforcement actions by the department included the following:

![]() 1,131 new criminal healthcare fraud investigations were opened.

1,131 new criminal healthcare fraud investigations were opened.

![]() 2,032 healthcare fraud criminal investigations were pending.

2,032 healthcare fraud criminal investigations were pending.

![]() 452 cases with criminal charges were filed, involving 892 defendants.

452 cases with criminal charges were filed, involving 892 defendants.

![]() 826 criminal convictions were made.

826 criminal convictions were made.

![]() 885 new civil investigations were opened.

885 new civil investigations were opened.

![]() 1,023 civil healthcare fraud cases were pending.

1,023 civil healthcare fraud cases were pending.

Each year, the OIG publishes a work plan to define its areas of focus for the coming year. For 2013, some of the “hot” topics were the following:

![]() Hospitals

Hospitals

![]() Same-day readmissions: Two DRGs paid instead of one

Same-day readmissions: Two DRGs paid instead of one

![]() Discharges versus transfers: Full DRG paid for discharge, only partial DRG for transfers

Discharges versus transfers: Full DRG paid for discharge, only partial DRG for transfers

![]() Mechanical ventilation time documentation: Must have 96 hours for certain higher-weighted DRGs

Mechanical ventilation time documentation: Must have 96 hours for certain higher-weighted DRGs

![]() Inpatient outlier payments: Inflation of costs to qualify as outlier

Inpatient outlier payments: Inflation of costs to qualify as outlier

![]() Nursing homes:

Nursing homes:

![]() Oversight of minimum data set: Accuracy of information

Oversight of minimum data set: Accuracy of information

![]() Hospitalizations of nursing home residents

Hospitalizations of nursing home residents

![]() Home health agencies

Home health agencies

![]() Prospective payment system documentation

Prospective payment system documentation

![]() Missing or incorrect OASIS data

Missing or incorrect OASIS data

![]() Home health face-to-face requirement: Physician must see the patient within 90 days before or 30 days into home health episode of care

Home health face-to-face requirement: Physician must see the patient within 90 days before or 30 days into home health episode of care

![]() Physicians:

Physicians:

![]() High utilization of sleep testing procedures

High utilization of sleep testing procedures

![]() Use of procedure modifiers during the global surgery period

Use of procedure modifiers during the global surgery period

![]() Place of service coding errors

Place of service coding errors

![]() Inappropriate payments for evaluation and management services

Inappropriate payments for evaluation and management services

Other areas reviewed include hospice, medical equipment and supplies, ambulance services, psychiatric facilities, and prescription drug issues. The OIG also reviews Part A and Part B contractors that process and pay claims (Wynia, 2000).

OIG Compliance Guidance

In response to the large number of identified compliance issues, the OIG has issued compliance program guidance papers for hospitals, nursing facilities, ambulance services, hospices, individual and small medical practices, third-party billing organizations, clinical laboratories, home health agencies, durable medical equipment and prosthetics and orthotics suppliers, and pharmaceutical manufacturers. Each addresses the seven critical components of an effective compliance program:

![]() Implementing written policies, procedures, and standards of conduct

Implementing written policies, procedures, and standards of conduct

![]() Designating a compliance officer and compliance committee

Designating a compliance officer and compliance committee

![]() Conducting effective training and education

Conducting effective training and education

![]() Developing effective lines of communication

Developing effective lines of communication

![]() Enforcing standards through well-publicized disciplinary guidelines

Enforcing standards through well-publicized disciplinary guidelines

![]() Conducting internal monitoring and auditing

Conducting internal monitoring and auditing

![]() Responding promptly to detected offenses and developing corrective action

Responding promptly to detected offenses and developing corrective action

![]() If the healthcare entity implements a compliance program that meets these criteria, it may be looked upon favorably should a future problem be identified by the OIG, as at demonstrates that it has made an effort to comply.

If the healthcare entity implements a compliance program that meets these criteria, it may be looked upon favorably should a future problem be identified by the OIG, as at demonstrates that it has made an effort to comply.

What Does This Have to Do with Coding?

Think about the implications of a diagnosis or procedure code equal to a certain number of dollars. Do the light bulbs go on? Is there a huge potential for increasing reimbursement through fraudulent coding? The answer is a most definite “yes.”

A survey of American doctors conducted in 2000 indicated that 39% admitted to having used tactics such as exaggerating symptoms, changing billing diagnoses, or reporting signs or symptoms the patients did not have in order to secure additional services felt to be clinically necessary (Hyman, 2001). A 2004 study found that “physicians whose practices include larger numbers of Medicaid or managed care patients seem more willing to deceive third-party payers than are other physicians. Deception may be a symptom of a flawed system, in which physicians are asked to implement financing policies that conflict with their primary obligation to the patient” (Bogardus, Geist, & Bradley, 2004).

One of the first signs of inappropriate or fraudulent inpatient coding is known as “DRG creep.” It can be identified when a hospital’s case mix index, or average of the total of the values assigned to all DRGs for that hospital’s patients, increases from year to year, or when the incidence of high-severity codes is found at a higher level than the incidence of that severity of disease is found in the population.

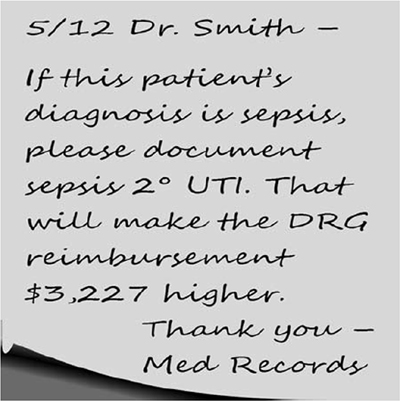

Although it would be nice to think that an increase in higher-weighted DRGs is due to improved physician documentation in the medical record, it could also be due to increased use of specialized expert software systems that identify potential diagnoses that could be used to maximize reimbursement. Once the needed diagnosis is identified, a “query form” can be sent to the physician to see if perhaps he or she “forgot” to document that condition in the chart. Rules for the use of query forms indicate they cannot lead the physician to document specifically to increase reimbursement. The sticky note illustrated in Figure 5-1 is an example of an inappropriate query.

Queries should be used in the following circumstances (American Health Information Management Association [AHIMA], 2008a):

![]() Clinical indicators of a diagnosis but no documentation of the condition

Clinical indicators of a diagnosis but no documentation of the condition

![]() Clinical evidence for a higher degree of specificity or severity

Clinical evidence for a higher degree of specificity or severity

![]() A cause-and-effect relationship between two conditions or organism

A cause-and-effect relationship between two conditions or organism

![]() An underlying cause when admitted with symptoms

An underlying cause when admitted with symptoms

![]() Only the treatment is documented (without a diagnosis documented)

Only the treatment is documented (without a diagnosis documented)

![]() Present on admission (POA) indicator status

Present on admission (POA) indicator status

FIGURE 5-1 Inappropriate query.

DRGs often occur in pairs or threes, one without a complication or comorbidity (CC) and one or two with. The latter always pay more.

Consider the following example:

DRG 460: Spinal fusion except cervical without major CC (weight = 3.8783)

DRG 459: Spinal fusion except cervical with major CC (weight = 6.5390)

DRG 460 without the complication or comorbidity is worth around $22,400, varying by geographic location and case mix index. Adding a major complication or comorbidity brings in an additional $15,000.

An analysis of 2006–2008 Medicare inpatient discharge data showed that documentation and coding improvements resulted in increased reporting of complications and comorbidities. The percentage of cases without a CC or major complication or comorbidity (MCC) dropped more than six points. Among DRGs that are split in some fashion based on secondary diagnoses, all but three demonstrated a pattern of large shift toward the higher-weighted, higher-severity DRGs (MedPac, 2010).

Other hospital abuses are specificity related. Coders are not supposed to make assumptions about diagnoses based on lab work or other diagnostic results in the chart. Coding is supposed to be based on physician documentation. However, in some facilities a positive culture report was a signal to coders that a bacterial diagnosis could be assigned, even without physician documentation. In January 2003, a whistle-blower suit brought by a coder at a Tennessee hospital alleged a number of DRG coding violations, including specific instructions to coders to upcode or use complications, even in the absence of complete chart documentation. The hospital settled for $2 million and the whistle-blower received $350,000.

CMS has identified additional healthcare settings with documentation and coding problems. A 2010 OIG report, “Questionable Billing Practices by Skilled Nursing Facilities,” found that 26% of claims submitted by skilled nursing facilities were not supported by medical record documentation (HHS, 2010). Time documentation to support the number of minutes for ultra high therapy billing was missing. Likewise, the OIG determined that home health agencies submitted 22% of claims in error because services were unnecessary or claims were coded inaccurately, resulting in $432 million in improper payments.

Coding is extremely complex. The rules differ depending on the site of service and who is submitting a bill. Because there are areas of coding that are open to interpretation, it is often the case that coding errors are mistakes, not intentional. This can be taken into account by investigators if they see mistakes but not a pattern of “mistakes.” An example would be investigation by the OIG into the correct assignment of principal diagnosis codes. According to official diagnosis coding guidelines, when a patient has a urinary tract infection, that code is sequenced first, before the code for the organism. If the order of the codes is switched, then a DRG with a higher weight is assigned. If all the cases of this type in a hospital were sequenced improperly, that facility might be charged with intentional fraud. In another facility, if only a few cases were improperly sequenced, no pattern would be identified, and the facility would have to refund money, but it is unlikely that the facility would be accused of fraud (Prophet, 1997).

Coders, even in settings such as physician offices, confront ethical dilemmas on a daily basis. As employees, they want to see their organizations succeed financially. As professionals, they want to adhere to the standards of conduct and ethical principles defined by their professional organizations. The Standards of Ethical Coding of the American Health Information Management Association (2008b) defines expected behavior among coders:

Coding professionals should:

1. Apply accurate, complete, and consistent coding practices for the production of high-quality healthcare data.

2. Report all healthcare data elements (e.g., diagnosis and procedure codes, present on admission indicator, discharge status) required for external reporting purposes (e.g., reimbursement and other administrative uses, population health, quality and patient safety measurement, and research) completely and accurately, in accordance with regulatory and documentation standards and requirements and applicable official coding conventions, rules, and guidelines.

3. Assign and report only the codes and data that are clearly and consistently supported by health record documentation in accordance with applicable code set and abstraction conventions, rules, and guidelines.

4. Query provider (physician or other qualified healthcare practitioner) for clarification and additional documentation prior to code assignment when there is conflicting, incomplete, or ambiguous information in the health record regarding a significant reportable condition or procedure or other reportable data element dependent on health record documentation (e.g., present on admission indicator).

5. Refuse to change reported codes or the narratives of codes so that meanings are misrepresented.

6. Refuse to participate in or support coding or documentation practices intended to inappropriately increase payment, qualify for insurance policy coverage, or skew data by means that do not comply with federal and state statutes, regulations, and official rules and guidelines.

7. Facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration in situations supporting proper coding practices.

8. Advance coding knowledge and practice through continuing education.

9. Refuse to participate in or conceal unethical coding or abstraction practices or procedures.

10. Protect the confidentiality of the health record at all times and refuse to access protected health information not required for coding-related activities (examples of coding-related activities include completion of code assignment, other health record data abstraction, coding audits, and educational purposes).

11. Demonstrate behavior that reflects integrity, shows a commitment to ethical and legal coding practices, and fosters trust in professional activities.

Preventive Measures

Coding managers and others involved in the process of coding for reimbursement purposes should be proactive in identifying potential risk areas. Comparative data are available for all types of facilities to compare their DRG, APC, or other payment category results to national or regional norms. Using outside auditors to review coding practices and patterns is advisable to increase objectivity. Billing system edits and payer rejection data are good sources of information to prompt educational efforts for coders.

In June 2004, the OIG published “Draft Supplemental Compliance Program Guidance for Hospitals.” It focuses on activities that are most likely to represent a potential source of liability. It includes the following onerous statements (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005):

Perhaps the single biggest risk area for hospitals is the preparation and submission of claims or other requests for payment…. Common and longstanding risks associated with claims preparation and submission include inaccurate or incorrect coding, upcoding, unbundling of services, billing for medically unnecessary services or other services not covered by the relevant health care program, billing for services not provided, duplicate billing, insufficient documentation, and false or fraudulent cost reports.

The need to monitor and improve coding and documentation practices is ongoing and necessary to ensure payment accuracy.

References

American Health Information Management Association. (2008a). Managing an effective query process. Journal of AHIMA, 79(10), 83–88.

American Health Information Management Association. (2008b). AHIMA Standards of Ethical Coding. Retrieved December 16, 2013, from http://library.ahima.org/xpedio/groups/public/documents/ahima/bok2_001166.hcsp?dDocName=bok2_001166

Bogardus, S., Geist, D. E., & Bradley, E. H. (2004). Physicians’ interactions with third-party payers: Is deception necessary? Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(17), 1941.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (n.d.). Description of civil monetary penalties (CMPs). Retrieved December 13, 2013, from http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/index.asp

Hyman, D. A. (2001). Health care fraud and abuse: Market change, social norms, and the trust reposed in the workmen. Journal of Legal Studies, 30, 531–567.

MedPac. (2010, March). Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy 2010. Retrieved December 16, 2013 from http://medpac.gov/chapters/Mar10_Ch02A_APPENDIX.pdf

Prophet, S. (1997). Fraud and abuse implications for the HIM professional. Journal of AHIMA, 68(4), 52–56.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. (2005, January 31). Draft supplemental compliance guidance for hospitals. Federal Register, 70(19), 4859–4860.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. (2010, December). Questionable billing by skilled nursing facilities. Report OEI-02-09-00202. Washington, DC: Office of Evaluation and Inspection Services.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. (2013). Healthcare Fraud and Abuse Control Program report, fiscal year 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2013, from http://oig.hhs.gov/publications/docs/hcfac/hcfacreport2012.pdf

Wynia, M. (2000). Physician manipulation of reimbursement rules for patients: Between a rock and a hard place. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283(14), 1861.